®

The Phonology of Lopit and

Comparison of Dialects

Timothy M. Stirtz

SIL International

®2014

SIL Electronic Working Papers 2014-004, May 2014

© 2014 SIL International®

Five of the six Lopit dialects of South Sudan have at least 90% lexical similarity and are rightly called dialects of the same language. Nevertheless, 60% of words differ in at least two dialects. In addition, the same phonemes, syllable types, and morphological alternations can be claimed for all the dialects with few exceptions. Although there are some common alternation patterns among the dialects, the

Abstract

1.2.3 Vowel distribution in two adjacent syllables of roots

1.3 Syllables

2.1 Dialect comparison of lexical similarities and identical words

2.2 Consonant alternations among dialects

2.3 Vowel alternations among dialects

2.4 Dialect comparison of syllable structure

2.5 Noun plural formation alternation among the dialects

2.6 Vowel morphophonology in other dialects

2.7 Consonant morphophonology in other dialects

2.8 Dialect alternation of prefixes

3 Summary

Appendix Aː Dialect comparison wordlist Appendix Bː Lopit villages in dialect areas

References

Lopit (ISO code [lpx]) is an Eastern Nilotic, Eastern Sudanic, Nilo-Saharan language. It is related to Otuhu, Dongotono, Lango (of South Sudan), Lokoya, and more distantly related to Bari, Kakwa, Mandari, and Toposa. The Ethnologue (Lewis et. al. 2013) states there are 50,000 Lopit speakers who mainly live in the Lopit Hills northeast of Torit, South Sudan.

There are six dialects of Lopit (Moodie 2012): namely, Ngabori, Dorik, Ngotira, Lomiha, Lohutok, and Lolongo. Turner (2001) analyzes the phonology of Lopit, using language resource people from the Lolongo dialect. In his verb analysis primarily using the Dorik dialect of Lopit, Moodie (2012) also gives a brief phonology. This paper analyses the phonology of the Ngotira dialect of Lopit, and makes

comparisons with four other dialects where they differ. Only Ngabori, which is reported to be nearly the same as Dorik, is not represented1.

Although 60% of words are segmentally different in at least two dialects, all dialects are at least 90% lexically similar with each other. The dialects share nearly all of the same phonemes, syllable structures, and phonological processes. And although there are some common alternation patterns among the dialects, the alternations, as well as which dialects alternate are mostly unpredictable.

This analysis is based on 285 nouns in singular and plural form and 60 imperative verbs, all collected in each of five Lopit dialects. The tone analysis is more tentative in that it is based on the tone of 200 Ngotira noun roots and the corresponding number forms of 120 of each of these nouns.

In the first half of the paper, I describe phonological aspects of the Ngotira dialect, in which I first discuss consonant and vowel phonemes, showing contrastive pairs and their distribution in sections 2.1– 2.2; secondly, syllable structure and interpretation of ambiguous segments in 2.3, and some tone features in 2.4; and thirdly, various morphological processes in 2.6–2.8, including vowel alternations, consonant alternations, and tone alternations. In the second half of the paper, I compare the Lopit dialects based on their similarity in the wordlist of appendix A, and how they differ or are similar in their phonological aspects to Ngotira.

1 Phonology of Lopit

1.1 Consonants

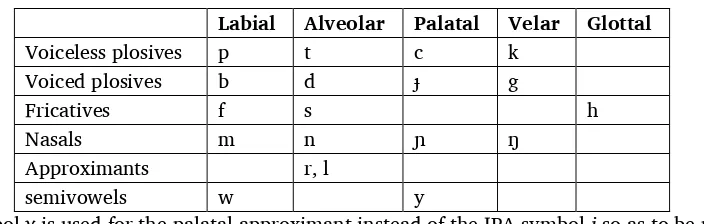

The 23 consonant phonemes of table 1 are found in the Ngotira dialect of Lopit.

Table 1. Consonant phonemes

Labial Alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal

Voiceless plosives p t c k

The symbol y is used for the palatal approximant instead of the IPA symbol j so as to be more easily

seen in the data in contrast with ɟ.

1 Special thanks to language resource persons: Valente Otwari Ladu (Dorik), Achaha Samuel Nartisio (Ngotira),

Caesar Ongorwo Bong (Lomiaha), Philip Horiho Odingo (Lohutok), and Paul Ahatar Gilbert (Lolongo).

The related language Otuho (Coates 1985) has the additional phonemes /θ/ and /đ/ (voiced alveolar tongue blade flap).

1.1.1 Consonant distribution

The data in (1) show that all Ngotira Lopit consonants can occur word-initial and intervocalically. Nasals

/m/, /n/, /ɲ/, /ŋ/, the fricatives /f/, /s/, and the approximants /l/, /r/ surface word-final, but not the

fricative /h/ or the semivowel /w/. The voiceless plosives /t/, /k/ also occur word-final, but the voicing contrast present between these plosives and /d/, /g/ in other environments is neutralized word-final. Note that unless a hyphen is present, the words of (1) and following examples are analyzed to be mono-morphemic in that they cannot reasonably be divided into two or more attested roots or affixes found in the data.

(1) Word-initial Intervocalic Word-final

p pír ‘point’ ipɔtit ‘brush’

t tuluhu ‘squirrel’ mɔ̀tì ‘pot’ tàmɔ̀t ‘bull’

c ciwali ‘flute, instrument’ ícɛ́t ‘dancing ornament’

k kɔ̀rì ‘giraffe’ akaf ‘hold up, raise’ bàtàk ‘pig, hog’

d – r dɔ̀rɔ̀ŋ ‘barren high land’ rɔ̀fán ‘roof frame’

In (3), voiced and voiceless plosives are shown to be contrastive at the beginning (B) and middle (M) of words. However, this contrast is neutralized at the end (E) of words.

(3) Neutralization of voicing contrast for word-final plosives

t – d B tɔ́mɛ́ ‘elephant’ dɔ́ŋɛ́ ‘mountain’

Word-final plosive phonemes surface as voiceless in the intervocalic environment resulting when the plural noun suffix -i is attached. We can assume the word-final plosives are voiceless in the underlying form since they are not voiced in the intervocalic environment. Root-final /k/ is merely

weakened to /h/ as in ìtàh-í ‘ostriches’, a process further discussed in section 2.7.

(4) Word-final /t/, /k/

t tàmɔ̀t ‘bull’ tàmɔ́t-ì ‘bulls’

k ítàk ‘ostrich’ ìtàh-í ‘ostriches’

As shown in the pairs of words in (5) there is some evidence for contrastive consonant length in

roots. Since there are unambiguous CVC syllables such as in fɔ̀k ‘earth’, lengthened consonants are

analyzed as two of the same consonant occurring across adjacent syllables (C.C) such as in hìt.tɔ ‘anus’

with initial CVC syllable. In this analysis, there is no need to posit extra phonemes such as /tː/, /dː/, /lː/,

(5) Contrastive consonant length

As discussed in section 1.3.2 there are no unambiguous consonant sequences in Lopit such as

word-medial non-geminate consonant sequences (*C1.C2). Thus, it can be posited that the first of two adjacent

consonants assimilates to the second consonant in all its features, provided that neither of these consonants are the semivowels /y/ or /w/.

(6) Assimilation of adjacent consonants

word-medial C1C2→ C2C2, where C1 and C2 ≠ /y/ or /w/

As shown in section 2.3.2, there is evidence for this process happening through morphology. When the singular suffix -ti is attached to the root-final /r/ of hɔ̀fìr ‘hairs’, the /r/ and /t/ become /tt/ in the singular noun hɔ̀fít-tî ‘hair’.

Alternatively, lengthened consonants could be analyzed as single-unit syllable onsets (.C:) rather than two of the same consonant occurring across adjacent syllables. In such an analysis, the contrastive consonant length would be a fortis/lenis or strong/weak distinction. Such an analysis adds at least the six consonant phonemes /t:/, /d:/, /l:/, /r:/, /w:/, /y:/ and is therefore not taken in this description.

In (7), /k/ and /h/ are shown to be contrastive at the beginning and middle of words. However, this contrast does not occur at the end of words in that /h/ does not occur word-final.

(7) Neutralization of /k/-/h/ contrast word-final

k – h B kɔ̀rì ‘giraffe’ hɔ́tɔ́ ‘blood’

M ikubɔri ‘hunt’ ihuma ‘do’

E bàtàk ‘pig, hog’ ---

In roots, the surface form of intervocalic /h/ varies depending on the speed of the utterance, speaker and word. However, the surface form of /h/ corresponds often to the alternations of (8).

(8) Alternation of /h/

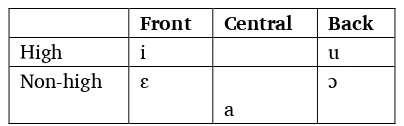

Table 2. Vowel phonemes

Turner (2001ː40) proposes a 9-vowel system in his description of the Lolongo dialect of Lopit. In

this description, the four vowels of table 2 have a corresponding [+ or – ATR] vowel ([i]-[ɪ], [u]-[ʊ],

[e]-[ɛ], [o]-[ɔ]). Moodie (2012ː16) acknowledges a 9-vowel system in the Dorik dialect of Lopit, but

mostly ignores the [ATR] distinction in his transcription of data.

The [ATR] distinction explains the vowel contrast between hʊ́tʊ́k ([-ATR]) ‘mouth’ and bùsùk

([+ATR]) ‘bull’. However, it causes us to ask why there is no [ATR] contrast for the vowels /i/, /ɛ/ and

/ɔ/. Perhaps a contrast with these vowels will be found in a larger data set, or perhaps only certain

speakers or dialects are aware of the [ATR] contrast in these vowels. The speakers I worked with from five different dialects were not aware of and did not speak with an [ATR] distinction in the data for this analysis2.

1.2.1 Vowel distribution in word positions

All Lopit vowels occur in word-medial and word-final positions. The vowels /i, ɛ, a/ occur in word-initial

position of a few nouns.

(9) Word-initial Word-medial Word-final

i ítàk ‘ostrich’ hìɟì ‘middle’ hárí ‘river’

The words with contrastive pairs of vowels in (10) show that each of the vowels are phonemes.

2 In analyzing the vowels, I relied both on speaker intuition and on my own hearing. That is, each of 285 nouns were

written in all dialects on slips of paper and sorted according to the syllable structure of the Ngotira dialect. After reading each noun, the Lopit speakers from five different dialects sorted the Ngotira words into piles as a group effort, arriving at a consensus for each placement decision. The result was five different vowel piles for each syllable structure. It was only when I pointed out the difference in vowel quality of hʊ́tʊ́k ‘mouth’ that the speakers separated this word into a sixth pile. Apparently the speakers were not even aware of the sound difference for this word until I pointed out the difference. I did not hear a difference in [ATR] vowel quality for other vowel pairs ([i] – [ɪ], [e] – [ɛ], [o] – [ɔ]) in any of the Lopit data, although I have heard this difference clearly in Mandari and other Eastern Sudanic languages.

(10) i – ɛ sìhɛ̂t ‘chicken comb’ sɛhi ‘thing, property’

1.2.3 Vowel distribution in two adjacent syllables of roots

The Ngotira data of (11) show that all possible combinations of vowels in adjacent syllables of roots are found. There are no co-occurance restrictions on vowels in adjacent syllables, and the same vowel distribution in two adjacent syllables of roots occurs in other Lopit dialects.

(11) Vowel distribution in adjacent syllables

i, i ìdîs ‘shadow’ ɔ, i mɔ̀tì ‘pot’

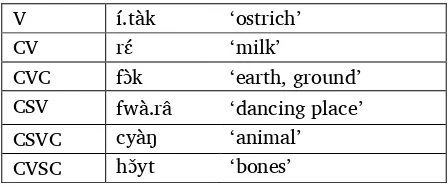

The syllable type V only occurs word-initial, and the syllable type CVC only occurs word-final in unambiguous syllable constructions. Monomorphemic nouns are most commonly disyllabic, but may also be monosyllabic or trisyllabic.

Syllable structures with semivowels in complex onsets and codas are given in (13). CSV syllables are only found in word-initial position of disyllabic words, and only with the semivowel /w/. CSVC and CVSC are only found in monosyllabic words.

(13) Syllable structures with semivowels in complex onsets and codas

/y/ /w/

CSV.CV fwàrâ ‘dancing place’

CSV.CVC mwárák ‘animal horn’

CSVC kyɛ́r ‘sheep’ kwàn ‘body’

CVSC hɔ̌yt ‘bones’

As shown in (14), the semivowels /w/, /y/ can also be the only consonant in onsets and codas. However, /w/ is not found in syllable-final position.

(14) Syllable structures with semivowels in simple onsets and codas

CV V.CVC CVC

w wɔ́ttì ‘cow dung’ áwɔ́ŋ ‘monkey’ háy ‘rain’

y yáyá ‘porcupines’ mìyàŋ ‘grass’

As mentioned above, CVC syllable constructions only occur unambiguously in word-final position. However, they are also analyzed to occur in word-initial position, when semivowels either fill the coda slot of the CVC syllable (lɛ́ymɛ̀ ‘lion’), or when semivowels fill the onset slot of a syllable following a CVC

syllable (ŋádyɛ́f ‘tongue’). In the resulting consonant sequences of such words, the semivowels /y/ can be

the first consonant (lɛ́ymɛ̀ ‘lion’), and both /y/ and /w/ can be the second consonant (ŋádyɛ́f ‘tongue’,

hɔ̀rwɔ̀ŋ ‘back’). However, /w/ is not found to be the first consonant of a sequence (except when it

geminates, as in hàww-ɛ̀‘arrow’).

(15) Syllable structures with semivowels in consonant sequences

/y/ /w/

1.3.2 Ambiguous segments

Regarding ambiguous segments, I first consider three alternatives to analyzing syllable types as having semivowels in complex onsets and codas; that is, they could be: (1) vowel sequences, (2) vowel glides, or (3) prenasalized and labialized consonants. I now discuss why each of these alternate analyses is not preferred.

The semivowels in complex consonant onsets and codas of (16) are not analyzed as vowel sequences for the following reasons: There are no unambiguous vowel sequences, such as two consecutive non-high vowels. Rather, all adjacent vowels involve at least one high vowel, which is analyzed as a semivowel /y/ or /w/. Furthermore, there is no contrastive vowel length. When analyzed as semivowels, all high vowels to adjacent to other vowels in the same syllable fill the S slot of CSV, CSVC or CVSC syllable types, and there is no need for syllable types such as CVV or CVVC.

(16) Semivowels in complex consonant onsets and codas:

kyɛ́r ‘sheep’

hɔ̌yt ‘bones’

kwàn ‘body’

fwàrâ ‘dancing place’

A second alternate analysis is that there are on and off vowel glides. Such an analysis removes the

need for the syllable types CSV, CSVC, CVSC. For example, CSVC words such as cyàŋ ‘animal’ would then

be CVC (cⁱàŋ). It also removes the need for CVC syllables in non-final position, which is advantageous in

that CVC syllables are only unambiguous in word-final position. CVC.CV words such as bɛ̀lyɛ̌ ‘skin’ would

be CV.CV (bɛ̀lⁱɛ̌). However, such an analysis is not taken because it would add at least the 9 vowel glide

phonemes /ⁱɛ, ⁱa, ⁱɔ, ⁱu, ᵘa, ᵘɔ, ɛⁱ, aⁱ, ɔⁱ/.

(17) Semivowels preceding vowels Vowels preceding semivowels

yɛ bɛ̀lyɛ̌ ‘skin’ ɛy lɛ́ymɛ̀ ‘lion’

Thirdly, the consonants immediately preceding semivowels are not analyzed as being labialized or

palatalized, since this analysis would require at least the 17 additional consonant phonemes /tʷ, cʲ, kʲ,

kʷ, bʷ, dʲ, dʷ, fʲ, fʷ, sʲ, sʷ, mʷ, nʷ, lʲ, lʷ, rʲ, rʷ/. There are at least 7 consonants that can precede the semivowel /y/, and at least 10 consonants that can precede the semivowel /w/. In additon, this analysis

does not account for the semivowels immediately preceding other consonants, such as in lɛ́ymɛ̀ ‘lion’,

(18) Consonants preceding semivowels

/y/ /w/

n ---- hinwara ‘ash’

l bɛ̀lyɛ̌ ‘skin’ lɔlwari ‘dry ground’

r hàryɛ̂ ‘night’ ŋɔ̀rwɔ̀ ‘wives’

Lengthened consonants are analyzed to be two of the same consonant across adjacent syllables

(VC.CV) rather than single-unit syllable onsets (V.CːV). As mentioned in section 1.1.2, the geminate

consonant analysis eliminates the need for the phonemes /tː/, /dː/, /lː/, /rː/, /wː/, /yː/. Instead, the CVC syllable type that unambiguously occurs in final position is analyzed as also occurring in word-initial position, having the same consonant coda as the consonant onset of the following syllable.

(19) Word-medial lengthened consonants

tt hìttɔ̀ ‘anus, source, root, beginning’ dd hàddɛ̀ ‘roots’

As in related languages, Lopit is analyzed to have two underlying level tones, High and Low, as in hɔ̀y

‘you sg.’ and hɔ́y ‘us’. Contour tone consists of more than one level tone on the same syllable. The

syllable is the tone-bearing unit, and at most two tones are allowed on the same syllable. Rising tone such as in hɔ̌yt ‘bones’ and bɛ̀lyɛ̌ ‘skin’ is rare. Falling tone is common on the final syllable of words, but rare elsewhere, as in bɔ̂rɛ̀ ‘stable’ and hɔ̀fît-tî ‘hair-sg.’ The lexical function of tone is low in that there are few tone minimal pairs. The grammatical distinctions of case and noun plural formation can be made solely by tone, and are discussed in section 1.8.

Noun tone melodies are represented by the nouns in isolation of (20–21), where the number of nouns with the given tone and syllable structure is shown to the left of each noun. There are four tone melodies in (C)VCV and (C)VCVC syllable structure of nouns, besides combination tone melodies, which indicates a system with two underlying level tones.

(20) Singular noun root Plural noun root

(21) Singular noun root Plural noun root

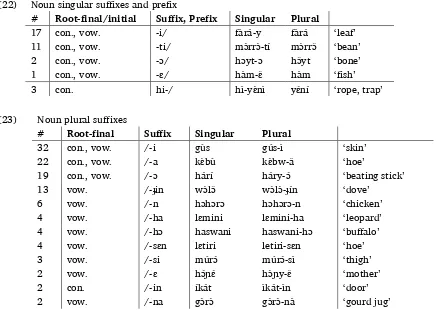

I now discuss the morphophonology of Ngotira Lopit. Sound alternations across morpheme boundaries include vowel alternations (1.6), consonant alternations (1.7), and tone alternations (1.8). Noun plural formation is briefly described in section 1.5 to assist the reader in following the noun examples of later sections. For further explanation of Lopit morphology and syntax, see the Lopit Grammar Book (Ladu et al. 2014).

1.5 Noun plural formation

There are three ways that nouns have singular and plural forms. As shown in table 4, nouns can attach various suffixes or a certain specific prefix to mark the singular form, as in hàddɛ́-tí ‘root-sg’ or hì-yɛ̀nì

‘sg-rope’. They can attach suffixes to mark the plural form as in cyàŋ-ì ‘animal-pl’, or they can mark both the

singular and plural form as in hi-ɲaŋ/ɲaŋ-i ‘sg-crocodile/crocodile-pl’. A suffix or prefix before the slash indicates affixation on singular nouns, whereas following the slash indicates affixation on plural nouns.

Table 4. Three segmental ways of forming singular and plural nouns

Suffixes, Prefix Singular noun Root Plural noun

-ti/ hàddɛ́-tí hàddɛ̀ hàddɛ̀ ‘root’

hi-/ hì-yɛ̀nì yɛ́ní yɛ́ní ‘rope’

/-i cyàŋ cyàŋ cyáŋ-ì ‘animal (general)’

hi-/-i hi-ɲaŋ -ɲaŋ- ɲaŋ-i ‘crocodile’

The noun system has multiple singular and plural marker suffixes, the most common of which are listed in (22–24). They are listed according to the number of nouns found to attach the suffix or prefix. The suffixes are mostly unpredictable as to which root they attach, by either the root-final segments or by the semantics of the root. Vowel-initial suffixes attach to roots with either vowel or consonant-final roots. Consonant-initial suffixes attach to vowel-final roots, and only rarely to consonant-final roots.

(22) Noun singular suffixes and prefix

# Root-final/initial Suffix, Prefix Singular Plural

(24) Combinations of singular and plural affixes

In addition, there are three nouns that only differ by tone in singular and plural form.

(25) Nouns that differ only by tone in singular and plural form

# Root-final Suffix Singular Plural

3 vow. Tone/Tone yànì yání ‘tree (general)’

1.6 Vowel morphophonology

When certain vowels are joined at morpheme boundaries in noun plural formation, they become

semivowels. As represented by the formation rule of (26), root-final /i, ɛ/ become /y/ before a

vowel-initial suffix; root-final /u/ becomes /w/ in the same environment, and a suffix-vowel-initial /i/ becomes /y/ following a root-final non-high vowel.

(26) Semivowel formation

i, ɛ → y / ____ + V u → w / ____ + V i → y / a, ɔ, ɛ + ____

In (27), the number of nouns with the given plural or singular suffix and root-final vowel is shown. Before a vowel-initial suffix, the root-final vowel /u/ becomes /w/ as in kɛ̀bù/kɛ̀bw-â ‘hoe’ and the root-final vowels /i, ɛ/ become /y/ as in ɟànî/ɟàny-â ‘broom’. In this process, the non-high root-final vowel /ɛ/ is raised to the high semivowel /y/ as in tɔ́mɛ́/tɔ̀my-â ‘elephant’. In addition, a suffix-initial /i/ becomes /y/ following the root-final low vowel as in rísá/rìsâ-y ‘tail’. In Mandari (Stirtz 2014), root-final

/ɛ/ and /ɔ/ become the semivowels /y/ and /w/ respectively, when vowel-initial suffixes are attached.

(27) Semivowels resulting from vowels joined through morphology

Depending on the speaker, when some words such as fɛ́rɛ́/fɛ̀rì.à ‘spear’ are said slowly, the suffix-initial vowel is juxtaposed to the root-final vowel, introducing a new syllable. At normal speed, such words have a semivowel (fɛ́rɛ́/fɛ̀ryà ‘spear’).

When the singular suffix -i attaches to hìkwà ‘thorns’, there is a resulting semivowel /y/ in the

singular hìkwâ-y ‘thorn-sg’. However, when the plural suffix -i attaches to the word ŋìryà ‘porridge’ with

the same syllable structure, /y/ is inserted as a syllable onset (ŋìríyà-y ‘porridges’), and thus increases the number of syllables. This is the only word found with this alternate solution of insertion for joined vowels.

Nearly all nouns have the same root vowels in both singular and plural forms. But root vowels alternate between the singular and plural form in ‘sheep’, ‘knife’, ‘fat’ and ‘oribi monkey’ as shown in (50). Nouns that do not have vowel alternations are given for comparison.

(28) Nouns with vowel alternations

Root vowel Singular Plural

hɔ́tɔ́‘blood’; ikubɔri ‘hunt’ – ihuma ‘do’). However, in the intervocalic environment resulting when the

plural suffixes -i, -a, -ɔ, -ɛ are attached to root-final /k/, the /k/ weakens to an allphone of the phoneme

/h/ as represented by the rule of (29).

(29) Morphological alternation of /k/ k → h / ____ + V

Depending on the suffix vowel attached, the /h/ is realized as the allophones [x], [ɣ] or [h]

according to the phonological alternations of /h/ in (8) (/h/ becomes [x] before /a/ or /ɔ/, [ɣ] before

/ɔ/ or /u/, and [h] before /i/ or /ɛ/). The nouns of (30) are shown to alternate in this way.

Singular Plural

There is some evidence for an alternation of /r/ to /t/ at morpheme boundaries. In (31), when the singular suffix -ti is attached to the root-final /r/ of hɔ̀fìr ‘hairs’, the /r/ and /t/ become /tt/ in the singular noun hɔ̀fít-tî [hɔfîttî] ‘hair’. This is an application of the assimilation rule of (6) that says the first of two adjacent consonants assimilates to the second consonant in all its features, provided that neither of these consonants are the semivowels /y/ or /w/.

(31) Nouns with morphological alternations of /r/

Suffix Singular Plural

-ti/ hɔ̀fît-tî hɔ̀fìr ‘hair, feather’

-ti/-u hut-ti hur-u ‘worm’

-ut/-tɔ múr-út mut-tɔ ‘neck’

-ɛ/-tin bɔ̂r-ɛ̀ bɔt-tin ‘stable’

Possibly, a similar alternation takes place for root-final /n/ in mán-á/mát-tà ‘farm’.

There is also evidence for an alternation of /t/ to /c/ before /y/ and a vowel, as represented by (57).

(32) Alternation of /t/ t → c / ____ yV

When the plural suffix -ɔ is attached to ŋátí ‘side, part’, /t/ becomes /c/ before the root-final /i/ that results as /y/ through semivowel formation (ŋàcy-ɔ̂ ‘sides, parts’). As shown in (18), no roots are found with /t/ before the semivowel /y/. So, the alternation of (32) can be analyzed to occur throughout the Ngotira dialect and not merely as a result of morphology. In Dorik, the /t/ remains in the plural nouns of (33) (ŋati-hɛn ‘sides, parts’, etc.) just as /t/ is present in the Dorik word tyaŋ ‘animal (general)’

instead of /c/ (cyàŋ) as in other dialects. Thus, an alternative analysis of the words of (33) having

suffixes in both singular and plural form (-ti/-cyɔ) is not warranted.

(33) Nouns with alternation of /t/

Suffix Singular Plural

/-ɔ ŋátí ŋàcy-ɔ̂ ‘side, part’

ɟátí ɟacy-ɔ ‘green vegetable’

mɔ̀tì mɔ̀cy-ɔ̂ ‘pot’

1.8 Tone morphophonology

I now briefly discuss the tone changes across morpheme boundaries in nouns, as well as case, which can be distinguished only by tone.

(34) Singular Plural Singular Plural

The plural suffix -a may have the allotones -â, -à with root Low replacement (LR) tone or -â with

root (LR) tone. The suffix -â attaches in màrìŋ/màrìŋ-â ‘fence’; the suffix -à (LR) attaches in ŋíɟím/ŋìɟìm-à

‘chin’ and the root High tone is replaced with Low tone; the suffix -â (LR) attaches in mwárák/mwàràh-â

‘horn’ and the root High tone is replaced with Low tone.

(35) Singular Plural Singular Plural

(C)VCV -â, -à (LR), -â (LR) (C)VCVC -à (LR), -â (LR)

(36) Singular Plural Singular Plural

The singular suffix -i may have the allotones -î, -í, -ì. The singular suffix -ti may have the allotones -tí, -tì.

(38) Singular Plural Singular Plural

-î, -í, -ì CVCV -í, -ì CVCVC

(39) Singular Plural Singular Plural

-î CVC -tí, -tì CVCV

H 2 mɔ́ɲí-tí mɔ́ɲí ‘intestine’

1 hàlá-tì hálá ‘tooth’

L 2 cɛ̀ŋ-î cɛ̀ŋ ‘animal’ 1 hàddɛ́-tí hàddɛ̀ ‘root’

LHL 2 mɔ̀rrɔ̀-tí mɔ̀rrɔ̂ ‘bean’

Plural formation of the three nouns of (40) is only by tone. Although tone is the only distinction between singular and plural form in these nouns, the tone differs in each noun. The root tone changes from singular to plural form are the same as in the nouns of (34) with the suffix -i (P). Thus, these nouns may have dropped or merged suffix -i, but kept the root tone changes caused by the suffix. Alternatively, one or more of the nouns of (40) may have previously had a different suffix that was dropped or merged. The noun hínɛ́/hìnɛ̀ ‘goat’ may have had the plural suffix -ɛ̂ as in hɔ́ɲɛ́/hɔ̀ɲy-ɛ̂ ‘mother’ and later dropped the suffix.

(40) Plural formation only by tone Similar tone in nouns with -i (P), -ɛ̂, -ɔ̂ (LR)

Tone Singular Plural Singular Plural

H/L hínɛ́ hìnɛ̀ ‘goat’ ígɛ́m ìgɛ̀m-í ‘work’ segmental suffix -ɔ still occurs in two other dialects of ‘pools’.

(41) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

buni bùnî buni buni buni-t ‘pool’

buni-cɔ bùnì buny-ɔ buny-ɔ buni

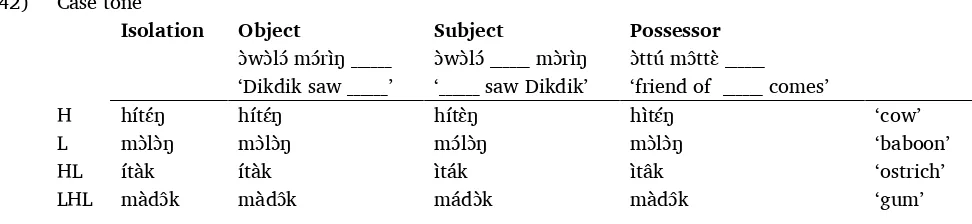

As shown in (42), tone also distinguishes at least accusative, nominative, and genitive case3. The

frames in which the data were elicited are shown above the words in each case.

3 To be a true comparison of tone, the noun slot should be clause-final in all three case frames. Or, it should first be

(42) Case tone

Isolation Object Subject Possessor

ɔ̀wɔ̀lɔ́mɔ́rìŋ ______ ɔ̀wɔ̀lɔ́ ______ mɔ̀rìŋ ɔ̀ttú mɔ̂ttɛ̀ ______

‘Dikdik saw ______’ ‘______ saw Dikdik’ ‘friend of ______ comes’

H hítɛ́ŋ hítɛ́ŋ hítɛ̀ŋ hìtɛ́ŋ ‘cow’

L mɔ̀lɔ̀ŋ mɔ̀lɔ̀ŋ mɔ́lɔ̀ŋ mɔ̀lɔ̀ŋ ‘baboon’

HL ítàk ítàk ìták ìtâk ‘ostrich’

LHL màdɔ̂k màdɔ̂k mádɔ̀k màdɔ̂k ‘gum’

2 Comparison of Lopit dialects

Having briefly discussed Ngotira Lopit phonology, I now make comparisons between Ngotira and other dialects of Lopit. I begin with a comparison of lexical similarities as well as words that are segmentally identical (2.1). Then I discuss dialect comparisons of consonants (2.2), vowels (2.3), syllables (2.4), noun plural formation (2.5), vowel morphophonology (2.6), and consonant morphophonology (2.7). Lastly, variation among dialects in derivational noun prefixes and inflectional verb prefixes are also discussed (2.8).

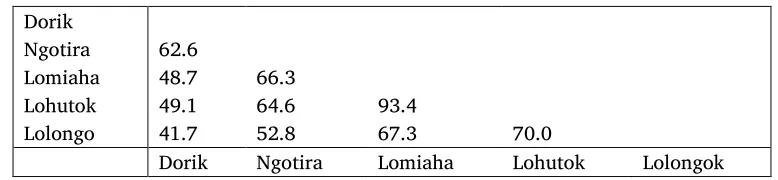

2.1 Dialect comparison of lexical similarities and identical words

The Lopit dialects are spoken on different mountains or sides of mountains in the Lopit mountain range running approximately north to south, northeast of the community of Torit. A list of village names in various dialect areas is given in appendix B. The northern most dialect is locally known as Ngabori, followed by Dorik, and so forth until the southern most dialect—Lolongo. The lexical similarities among five dialects shown in table 5 follow the geographic proximity of the dialects. Thus, the percentages of lexical similarity diminish moving down and to the left; that is, as the dialects are further spaced from each other. The percentages of table 5 are based on the dialect comparison wordlist in appendix A.

Table 5. Percentage of words lexically similar among Lopit dialects

Dorik

Ngotira 96.0

Lomiaha 93.6 96.6

Lohutok 93.4 96.3 99.7

Lolongo 90.7 93.1 94.3 94.4

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

In comparing the phonology of the dialects, I generally ignore the differences in lexemes among the dialects, and instead focus on patterns of alternation among the lexically similar words and morphemes of the dialects. Thus, it is important to also consider the percentage of words segmentally identical among the dialects, which are given in table 6. Note that the percentages of identical words are

significantly lower than the percentages of lexical similarity, and also diminish moving down and to the left, as the dialects are further spaced from each other. Only 39.2% of words are segmentally identical in each of five dialects. Thus, more than 60% of words are different in at least two dialects. The

Table 6. Percentage of words segmentally identical among Lopit dialects

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongok

2.2 Consonant alternations among dialects

Five Lopit dialects have the same consonants as table 1 with the exception of Dorik, which does not have the phoneme /s/. Words with /s/ in other dialects have /c/ in Dorik. Futhermore, five Lopit dialects have the same consonant distribution as in (1), and in addition, /b/ can be word-final in Dorik as in the

word hɔb ‘ground’. Although phonemes are nearly the same in all Lopit dialects, there are some notable

consonant alternations in some dialects, although which dialect has which alternation is not always predictable.

In the Dorik dialect, the phoneme /b/ can be word-final as in hɔb ‘ground’, whereas /b/ is not found

word-final in other dialects.

(43) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

hɔb fɔ̀k fɔw faw faw ‘ground’

In Dorik, which has no /s/ phoneme, /c/ is used instead of /s/ in all word positions.

(44) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

Word-initial cali sàlì sali sali sali ‘stove’

Intervocalic bucuk bùsùk busuk busuk busuk ‘bull’

Word-final guc gùs gus gus gus ‘skin’

All Lopit dialects have words with initial /l/, such as lɛ́ymɛ̀ ‘lion’. However, /l/ is elided word-initial in some Lomiaha and Lohutok words, and more frequently in Lolongo words.

(45) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

l lɛymɛ lɛ́ymɛ̀ lɛmyɛ lɛmyɛ lɛmɛ ‘lion’

l ~ ∅ lɔgulɛ lɔgulɛ lɔgulɛ lɔgulɛ ɔgulɛ ‘elbow’ l ~ ∅ lɔyami lɛyamɛ ɔyami ɔyami ɔyamɛ ‘wind’

However, in some words before a front vowel /i/ or /ɛ/, /l/ is used instead of /r/—either

word-initial or intervocalically in Lomiaha, Lohutok and Lolongo.

(46) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

r rɔrɔy rɔrɔy rɔrɔy rɔrɔy rɔrɔy ‘thing, issue’

r ~ l rɛ rɛ́ lɛ lɛ lɛ ‘milk’

r mariŋ màrìŋ mariŋ mariŋ mariŋ ‘fence, pen’

r ~ l hari hárí hali hali hali ‘club’

(47) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

In some words, intervocalic /k/ is weakened to /h/ in some dialects. However, the dialects in which

/k/ weakens to /h/ vary from word to word. Furthermore, in the word súhɛ́ ‘chest’, /h/ becomes /g/ in

the Dorik dialect.

tuhɛ lɔkuduk lɔhuruk lɔhuruk ɔhuruk ‘crow’ g tɔgɔli tɔgɔli tɔgɔli tɔgɔli tɔgɔli ‘canoe’

h ~ g cugɛ súhɛ́ suhɛ suhɛ suhɛ ‘chest’

Most other consonant phonemes are found in five dialects of the same word. However, in a few words there are other consonant alternations among the dialects.

(49) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

s cihɛt sìhɛ̂t sihɛt sihɛt sihɛt ‘chicken comb’

t tafar táfár tafar tafar tafar ‘lake, pond’

In the words ‘water turtle’, ‘hyena’ and ‘call’ of (50), consonant length alternates among the dialects. Although /nn/ is not found in the nouns or verbs of this analysis for any dialect, it occurs in

demonstratives and relative connectors such as ìnnâŋ ‘that, which’ in all dialects except Ngotira.

(50) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

Some lengthened consonants are found in more word positions in certain dialects. In these dialects, it may be preferable to analyze lengthened consonants as single-unit syllable onsets (.C:) so that they fit

into word-initial CV and CVC syllable types. Word-initial /ll/ occurs in the word llɛ́wá ‘gazelle type’ in

Lomiaha, Lohutok and Lolongo. Word-initial /tt/ occurs in the word ttim ‘bush, wilderness’ in Lohutok

and Lolongo. Word-medial /mm/ occurs in the word immadɔk ‘gum’ in Lomiaha, Lohutok and Lolongo.

(51) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

2.3 Vowel alternations among dialects

Five Lopit dialects have the same vowel distribution as (9), and in addition, Lomiaha, Lohutok and Lolongo have word-initial /ɔ/ as in ɔyiri ‘spirit’.

Most vowel phonemes are found in five dialects of the same word. However in some words, the vowel alternations seen in (52) occur among the dialects. And which dialect has which vowel, varies from word to word. ilɔma ilɔma ilama ilama ilama ‘distance’ ɛ ~ a ihɛrɛk ikarrak ikarrak ikarrak ikarrak ‘water turtle’

hayyɔhɔni hayyɔhɔni hɛyyɔhɔni hɛyyɔhɔni hɛyyɔhɔni ‘shepherd’

u ~ i hiwaru hiwaru huwaru huwaru huwaru ‘cat (general)’

hunɔm húnɔ́m hinɔm hinɔm hinɔm ‘cave’ huhɔy hikwɔy huhwɛ huhɛ huhɛ ‘charcoal’

hicu husuŋ husuŋ husuŋ hisuŋ ‘cows’

ɛ ~ i pir pír pɛr pɛr pɛr ‘bicycle’

u ~ ɔ cumay sɔ̀mây sɔmay sɔmay sɔmay ‘fat (n)’

a ~ i hanaci hanasi hanasɛ inasi hinasi ‘sister’

yɛ ~ ya hafyɛlay hafyalay hafyalay hafyalay hafyalay ‘claw’

iryɛtak iryɛtak iryatak iryatak iryatak ‘tie around neck’

In some words, a vowel without an adjacent semivowel alternates with a vowel and adjacent semivowel among the dialects. And which dialect has which vowel and semivowel, varies from word to word.

irɛfit irɛfit ilyɛfit ilyɛfit ɔlɛfit ‘container’ ɛ ~ ya imɛtak imɛtak imyatak imyatak imyatak ‘increase,

become’ inɛfɔ inɛfa inɛfu inyafa inyafa ‘catch’ lɔrɛwa lɛrɛwa lɔlyawa lɔlyawa ɔlɛwa ‘husband’ ɔ ~ wɔ idɔŋɔ idɔŋɔ idwɔŋɔ idwɔŋɔ idwɔŋɔ ‘appear’

hɔmwɔŋ hɔ̀mwɔ̀ŋ hɔmɔm hɔmɔm hɔmɔm ‘face, forehead’ ɛ ~ ɛy lɛymɛ lɛ́ymɛ̀ lɛmyɛ lɛmyɛ lɛmɛ ‘lion’

In a few other words, there are vowel-consonant alternations among the dialects.

(54) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

wa mɔrwari mɔrwari mɔrwari mɔrwari mɔrwari ‘rocky place’

wa ~ wa kwan kwàn wan wan hwan ‘body’

wa ~ usa ibwari ibwari ibusari ibusari oburusari ‘escape’

ca ~ tya icaha icaha ityaha ityaha ityara ‘begin’

cɔw ~ sw hɔcɔwan haswani haswani haswani haswani ‘buffalo’

llu ~ lyu tɛ-lyu tɛ-lyu tɔ-llu tɔ-llu tɔ-llu ‘jumb down’

sːi ~ syɔ ma-cɔhi may-syɔka ma-sːik ma-sːik ma-sːik ‘places’

a In Ngotira, ‘places’ can be either may-sihior may-syɔk.

2.4 Dialect comparison of syllable structure

Syllable types and structures are generally the same for the five dialects. However, CVSC syllable types

are not found in Lomiaha or Lohutok. However, the semivowel /w/ is found word-final in Lolongo faw

‘earth, ground’ in Lolongo.

Semivowels precede and follow the same vowels in other dialects as in (17), except that in Lomiaha,

Lohutok and Lolongo, /y/ does not precede /u/, but instead precedes /ɔ/ as in dyɔrɔ ‘rats’. In addition,

/w/ precedes /ɛ/ in Lomiaha huh-wɛ ‘charcoal’ and Lolongo ilulwɛ ‘cry’.

The same consonants precede semivowels in other dialects, except that in Dorik —which has no /s/

found to precede /w/. In addition to the Ngotira consonants preceding adjacent vowels shown in (18), /t/ precedes /y/ in Dorik as in tyaŋ‘animal’, and /ɟ/ precedes /y/ in Lolongo as in ɟyani ‘broom’.

Lastly, tone was only elicited for the Ngotira data in this analysis. However, Turner (2001ː44)

claims a two contrastive level tone system in Lolongo (High and Low), and Moodie claims at least High and Low tone in Dorik (2012ː15).

2.5 Noun plural formation alternation among the dialects

In other dialects, the same plural formation affixes are found except that Lomiaha, Lohutok and Lolongo do not have -sen, and these dialects use -ira instead of -ara. In Dorik, which has no phoneme /s/, the suffixes -ci and -cen are used instead of -si and -sen.

Most plural formation affixes are found in five dialects of the same word. However in some words, there are alternations of the affixes among the dialects. And which dialect has which alternation, varies from word to word. Which suffix alternates also varies from word to word. In (55), the plural suffix -a is shown to alternate with various suffixes and in various dialects. Singular forms of nouns are listed above plural forms in each of five dialects.

(55) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

fɔtir fɔ́tír fɔtir fɔtir fɔtir ‘warthog’

-a ~ -ak fɔtir-a fɔ̀tìr-à fɔrtir-ak fɔrtir-ak fɔrtir-ak

cali sàlì sali sali sali ‘stove’

-a ~ -cɔ, -tɔ cali-cɔ sàly-â sali-tɔ sali-tɔ sali-tɔ

In (56), the plural suffix -ɔ alternates with various suffixes and in various dialects.

(56) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

fuhɛr fúhɛ́r fuhɛr fuhɛr fuhɛr ‘farm’ -ɔ ~ -a fuhɛr-ɔ fùhɛ̀r-ɔ̀ fuhyar-a fuhyar-a fuhyar-a

buni bùnî buni buni buni-t ‘pool’

-ɔ ~ -cɔ, ∅ buni-cɔ bùnì buny-ɔ buny-ɔ buni

The alternations of the plural suffix -ɟin are similarly unpredictable.

(57) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

hɔfwɔ hɔ́fwɔ́ hɔfwɔ hɔfwɔ hɔfwɔ ‘flour’ -ɟin hɔfwɔ-ɟin hɔ̀fwɔ̀-ɟìn hɔfwɔ-ɟin hɔfwɔ-ɟin hɔfwɔ-ɟin

(57) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

The singular suffix -i also has unpredictable alternations.

(58) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

The singular prefix hi- is most common in singular nouns of all dialects, such as in hì-yɛ̀nì/yɛ́ní

‘rope’. However, hi- begins both singular and plural nouns in some dialects of the words of (59).

(59) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

Most nouns utilize the same mechanisms for forming singular and plural nouns in all dialects. That is, in most nouns, all dialects attach a suffix or prefix to the singular form, or they all attach a suffix to the plural form, or they use a combination of the two. However in the nouns of (60), the dialects alternate in the way they form the singular and plural of the noun.

(60) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

mwarah-i mwárák mwarah-ati mwarah-ati mwarah-ati ‘horn’

2.6 Vowel morphophonology in other dialects

In other Lopit dialects, the root-final vowels /u, i, ɛ/ also become the semivowels /w/ or /y/ before

vowel-initial suffixes. In addition, the suffix -i becomes the semivowel /y/ when attached to singular or plural nouns with root-final /a/.

In some dialects of certain words, there is rounding assimilation of the root vowel /ɛ/ to the plural

suffix -ɔ. alveolar /d/. However, /ɔy/ is common following alveolar consonants in other words such as hisyɔ ‘honey, oil’.

2.7 Consonant morphophonology in other dialects

In other dialects of Lopit, /k/, /r/, /t/ have the same morphological alternations as in Ngotira.

Consonant sequences are not found in roots or through morphology in Ngotira. However, in Dorik, the consonants ŋk are joined when the suffix -kɔ attaches to liŋ in the singular noun liŋ-kɔ ‘salt’, which has no plural form. The consonants ŋɲ in the Dorik singular noun ciŋɲati ‘sand’, again having no plural form, may also be joined through morphology. For still unknown reasons, the consonant sequence rt

occurs in the Lomiaha-Lohutok-Lolongo plural noun fɔrt-ir-ak ‘warthogs’, but not in the singular noun

fɔtir. To date, no other consonant sequences are found in the data of any dialect.

(63) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

ŋ-k liŋ-kɔ líŋ liŋ liŋ liŋ ‘salt’

ŋɲ ciŋɲati siŋɛta siŋatay siŋata siŋatɛ ‘sand’ fɔtir fɔ́tír fɔtir fɔtir fɔtir ‘warthog’ rt fɔtir-a fɔ̀tìr-à fɔrtir-ak fɔrtir-ak fɔrtir-ak

2.8 Dialect alternation of prefixes

In derivational noun prefixes, as well as in imperative verb prefixes, certain alternationsoccur among

the dialects.

The derivational noun prefix da- in Ngotira dá-mày ‘position’ may have originally been the

with vowel ɔ or u as in dɔ bɔk ‘in the stable’, and dɛ before a noun with vowel ɛ or i as in dɛ tim ‘in the forest’. In other dialects, there are other alternations for the same preposition, as shown in (64).

(64) Vowel of

The derivational prefix dɛ-, da-, ta- in ‘position’ has the same alternations in each of the dialects as

the preposition dɛ, da, ta, dɔ, tɔ ‘from, in, at’.

(65) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

ma-y mày ma-y ma-y ma-y ‘place’

ma-cɔhi may-syɔka ma-sːik ma-sːik ma-sːik

dɛ- ~ da- ~ ta- dɛ-ma-y dá-mày da-ma-y ta-ma-y da-ma-y ‘position’

dɛ-ma-cɔhi da-may-syɔk da-ma-sːik ta-ma-sːik da-ma-sːik

a In Ngotira, ‘places’ can be either may-sihi or may-syɔk.

The noun derivational prefix lɔ-, lɛ- may have similar alternations in each of the dialects as the

preposition lɔ, lɛ ‘for’.

The imperative verbs of (67) have an inflectional prefix tɛ-, ta-, tu-, tɔ-, ti- that alternates among the dialects in some verbs according to the root vowel.

(67) Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

With the present data for the Ngotira Lopit language, I propose 19 consonant phonemes; namely, (/p/,

/b/, /t/, /d/, /c/, /ɟ/, /k/, /g/, /f/, /s/, /h/, /m/, /n/, /ɲ/, /ŋ/, /r/, /l/, /y/, /w/), 5 vowel phomenes

(/i/, /ɛ/, /a/, /ɔ/, /u/), 6 syllable types (V, CV, CVC, CSV, CSVC, CVSC), and 2 underlying level tones

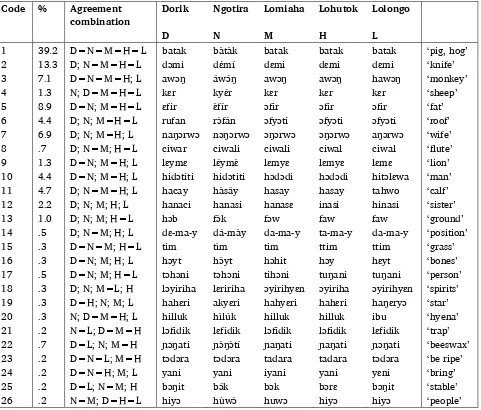

In table 7, all the Ngotira words of the second dialect column are in bold. If a word is segmentally different from the dialect word next to it, it is also in bold. The numbers in the Code column represent different combinations of dialect agreement. The percentage of words with each combination is given. In the Dialect Comparison Wordlist that follows, each word is labeled with the code number that represents the dialect agreement combination.

Table 7. Dialect agreement combination codes

Code % Agreement combination

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

D N M H L

21 .2 N=L; D=M=H lɔfidik lɛfidik lɔfidik lɔfidik lɛfidik ‘trap’

22 .7 D=L; N; M=H ɲɔŋati ɲɔ̀ŋɔ̀tí ɲaŋati ɲaŋati ɲɔŋati ‘beeswax’

23 .2 D=N=L; M=H tɔdɔra tɔdɔra tadara tadara tɔdɔra ‘be ripe’

24 .2 D=N=H; M; L yani yani iyani yani yɛni ‘bring’

25 .2 D=L; N=M; H bɔŋit bɔ́k bɔk bɔrɛ bɔŋit ‘stable’

26 .2 N=M; D=H=L hiyɔ hùwɔ̀ huwɔ hiyɔ hiyɔ ‘people’

In the list below, there are 285 nouns in singular and/or plural forms and 62 verbs in imperative form. Plural noun forms are listed below singular forms. For further information about each word, see the Lopit Dictionary (Ladu et al. 2014).

Dialect Comparison Wordlist

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

3 ha-ydihita-k ha-ydihita-k ha-ydihita-k ha-ydihita-k hɛtadihɔk

1 haɟaŋa-ti haɟaŋa-ti haɟaŋa-ti haɟaŋa-ti haɟaŋa-ti ‘fly’ n

12 hanac-ara hans-ara hanas-ira inasi-ra hinasi-ra

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

12 irac-ara haras-ara halasi-ra ilasi-ra hilasi-ra

5 hari hárí hali hali hali ‘club, stick’ n

1 ha-ruta-ni ha-ruta-ni ha-ruta-ni ha-ruta-ni ha-ruta-ni ‘inheritance’ n

1 ha-ruta-k ha-ruta-k ha-ruta-k ha-ruta-k ha-ruta-k

11 haca-y hàsâ-y hasa-y hasa-y tahw-ɔ ‘calf’ n

11 haca-k hàsà-k hasa-k hasa-k tahw-a

2 hɔcɔwan haswani haswani haswani haswani ‘buffalo’ n 6 hɔcɔwan-i haswani-hɔ haswani haswani haswani

1 hattɛl-i hattɛl-i hattɛl-i hattɛl-i hattɛli ‘egg’ n 3 hattɛl hattɛl hattɛl hattɛl hattɛly-ɔ

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

2 hipat-iti hipat-ita hipat-ita hipat-ita hipat-ita

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo 10 hiyɔr-rita hiyɔr-rita hiwɔŋita hiwɔŋita hiwɔlɔŋita

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

1 iburahini iburahini iburahini iburahini iburahini ‘attack’ v.t

9 icaha icaha ityaha ityaha ityara ‘begin’ v.t

1 idumɛlɛ idumɛlɛ idumɛlɛ idumɛlɛ idumɛlɛ ‘darkness’ n.sg

1 ifya ifya ifya ifya ifya ‘ask’ v.i

2 ikuma-hi ihuma-ha ihuma-ha ihuma-ha ihuma-ha

1 ihuma ihuma ihuma ihuma ihuma ‘do’ v.t

2 itahafu-ti ikafuti ikafuti ikafuti ikafuti ‘bat’ n

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

7 ikubɔ ikubɔri tɔlihari tɔlihari italihari ‘hunt’ v.t

1 illa ìllá illa illa illa ‘friend, brother’ n

5 ilɔlɔŋɔ ilɔlɔŋɔ illillɔŋɔ illillɔŋɔ illillɔŋɔ ‘call’ v.t 5 ilɔm-a ilɔma ilama ilama ilama ‘distance’ n.sg

11 ilɔm-ita --- --- --- ilama-ha

5 imɛtak imɛtak imyatak imyatak imyatak ‘increase, become’ v.i

13 inɛfɔ inɛfa inɛfu inyafa inyafa ‘catch’ v.t

10 irɛfit irɛfit ilyɛfit ilyɛfit ɔlɛfit ‘container (for milk)’

1 irumɔk irumɔk irumɔk irumɔk irumɔk ‘attack’ v.t

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

1 kurufat-i kurufat-i kurufat-i kurufat-i kurufat-i

10 kwan kwà-n wa-n wa-n hwa-n ‘body’ n

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

7 tuhɛ lɔkuduk lɔhuruk lɔhuruk ɔhuruk ‘crow’ n

7 tuhɛ-cɔ lɔkuduh-i lɔhuruh-i lɔhuruh-i ɔhuruh-i

3 lɔlwari lɔlwari lɔlwari lɔlwari ɔlwar ‘dry ground’ n.sg

22 cɔla lɔŋɔhɛ cala cala cɔla ‘compacted

cow manure’

n.sg

2 cɔla-cin --- --- --- ---

3 lɔrɔmɔri lɔrɔmɔri lɔrɔmɔri lɔrɔmɔri ɔrɔmɔri ‘digging place’ n.sg 5 lɔrwɔt-i lɔ́rwɔ́t-í ɔlwɔt-i ɔlwɔti ɔlwɔti ‘cannibal’ n 17 lɔrwɔt lɔ́rwɔ́t ɔlwɔt halwɔk halwɔk

1 lɔtwala lɔtwala lɔtwala lɔtwala lɔtwala ‘ash’ n.sg 11 lɔwɔtɔy lɔwɔtɛ lɔwɔtɛ lɔwɔtɛ ɔwɔtɛk ‘diarrhea’ n.sg

1 mɔrwari mɔrwari mɔrwari mɔrwari mɔrwari ‘rocky place’ n.sg

1 mɔrw-ɔ mɔrw-ɔ mɔrw-ɔ mɔrw-ɔ mɔrw-ɔ ‘stone’ n

1 mɔru mɔ́rú mɔru mɔru mɔru

1 mɔti mɔ̀tì mɔti mɔti mɔti ‘pot’ n

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

6 mwarah-i mwárák mwarah-ati mwarah-ati mwarah-ati ‘horn of

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo 1 rabɔlɔ rabɔlɔ rabɔlɔ rabɔlɔ rabɔlɔ

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo

1 tamu tàmù tamu tamu tamu ‘helmet’ n

2 tamu-cin tamw-ɔ tamw-ɔ tamw-ɔ tamw-ɔ

2 tira tara tara tara tara ‘is, be’ v.i

1 taturɔ taturɔ taturɔ taturɔ taturɔ ‘scatter’ v.t

Dorik Ngotira Lomiaha Lohutok Lolongo 10 turɛɲa turɛɲa turyana turyana hitɔrɛniti

The village names in each of the six South Sudanese Lopit dialect areas,4 as reported by the language

Buwara Logona wati Ihiran Idali

Lomerok Lobelo Mehejik Lodonyok

Lodo Lacarok Mura Lopit Losow

Haba Lodahori Habirongi Losinya

Lohomiling Lohinyang Hiyahi

4 The six dialects of Lopit are spoken in the Lopit Hills northeast of Torit in South Sudan, where the dialects of

Ngabori and Dorik are spoken on the northernmost mountain of the range, and the other dialects in the order mentioned below are spoken in consecutive mountains of this range going south, with Lolongo being the sourthern most dialect.

Coates, Heather. 1985. Otuho Phonology and Orthography. Occasional Papers in the Studies of Sudanese Languages. SIL. Juba, South Sudan 4:86–118.

Hall, Beatrice L. and Eluzai M. Yoke. 1981. Bari Vowel Harmony: The Evolution of a Cross-Height Vowel Harmony System. Occasional Papers in the Studies of Sudanese Languages. SIL. Juba, South Sudan 1:55–63.

Ladu, Valente Otwari, Achaha Samuel Nartisio, Caesar Ongorwo Bong, Philip Horiho Odingo, Paul Ahatar Gilbert. (2014). Lopit Grammar Book. Juba, South Sudan. SIL-South Sudan.

Ladu, Valente Otwari, Achaha Samuel Nartisio, Caesar Ongorwo Bong, Philip Horiho Odingo, Paul Ahatar Gilbert, Timothy M. Stirtz. (2014). Lopit Dictionary. Juba, South Sudan. SIL-South Sudan. Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.) 2013. Ethnologue: Languages of the World,

Seventeenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/language/lpx (accessed April 26, 2014).

Moodie, Jonathan. 2012. A Sketch of the Verbal System in Lopit. MA Thesis for the University of Melbourne.

Stirtz, Timothy M. (to appear). Mundari Mid-Vowel Raising in [ATR] Harmony, and other Phonology. Turner, Darryl. 2001. Lopit Phonology. SIL Sudan.