Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:16

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Cartel (In)Stability on Survivor Island

Franklin G. Mixon Jr.

To cite this article: Franklin G. Mixon Jr. (2001) Cartel (In)Stability on Survivor Island, Journal of Education for Business, 77:2, 89-94, DOI: 10.1080/08832320109599055

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320109599055

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 19

View related articles

Cartel (1n)StabiIity on

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Survivor Island

FRANKLIN

G.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

MIXON, JR.

University of Southern Mississippi Hattiesburg,

Mississippi

opular culture is increasingly

P

being used as a tool for teachingeconomics principles (Becker

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Watts,1995, 1998). Watts and Smith (1989), Kish-Goodling (1998), Trandel (1999), and Tinari and Khandke (2000) have offered novel uses of popular culture to illustrate economics concepts. Watts and Smith showed how literature and drama can be used to develop econom- ics principles, and Kish-Goodling (1 998) has offered teaching techniques

using Shakespeare’s Merchant

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Venicein a monetary economics class.

Trandel (1 999) pointed out that choic- es made by contestants on the (former) MTV game show Singled Out help explain the dominant strategy concept used by game theorists and microecono- mists. Tinari and Khandke (2000, p. 259) offered economics lessons through music lyrics. Their exercise involved over 100 students at two separate univer- sities and ultimately resulted in written assignments conveying macro- and microeconomics lessons gleaned from over 75 songs covering several different music genres. The benefits were summed up by the authors’ presentation of student assessments, which included such state- ments as, “It [the music project] was helpful in allowing us to see economics outside of the classroom context.”

The student quote above expresses a common sentiment among economics

ABSTRACT. In this study, the author investigates a recent phenomenon in American culture-reality-based tele- vision-as fertile ground for pedagog- ical examples. Specifically, the author examines cartel behavior among con-

testants on the 2000 edition of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

CBS’spopular reality show

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Survivor. Using anecdotes regarding contestant behav-ior on the show, the author examines incentives to both form cartels and cheat on cartel decisions.

students. It neatly summarizes the importance of attempting to develop teaching examples that students can relate to and understand. Trandel’s (1999) work is especially important in this regard because it was based on a game show developed by MTV, a very popular media outlet among young adults. Tinari and Khandke’s (2000) more recent work is also quite helpful in this regard. Finding other sources for creating such lessons continues to be important for modern-day economics educators.

In this article, I highlight the useful- ness of a more recent phenomenon in American culture as fertile ground for teaching examples. That phenomenon is the emergence of reality-based televi- sion, much of which has proven extremely popular with young adults. MTV was the pioneer of reality-based television development with the advent of its popular shows The Real World and

Road Rules. Both shows, which began

in the 1990s, follow the real lives of young adults (roommates) in various locales.’ The CBS television network has recently capitalized on MTV’s suc- cess by developing two new reality shows. One of these, Big Brother, is similar to MTV’s Real World, except that the roommate participants are vying for over $500,000 in prize money.2

Another show developed by CBS-

Survivor-is built on a survival theme.

In the 2000 edition of this show, 16 “contestants” were placed on a deserted island where they formed two “tribes” (Tagi and Pagong) that resided on sepa- rate sides of the island and engaged in “contests” resulting in expulsion (as in

Big B r ~ t h e r ) . ~ The two tribes periodical-

ly engaged in two types of challenges, reward and immunity challenges, which often represented physical contests (e.g., obstacle courses, swimming, rowing) between the two tribes. Reward chal- lenges offered various “luxuries” as rewards (e.g., food, wine, linens, etc.) to the winning tribe. These were important because the castaways otherwise were forced to provide their own food and shelter from the island’s resources. The second type of challenge was also important, given that only the losing tribe would be forced to “vote” one of its own members off of the island at a “trib- al council.” In other words, all members

NovembedDecember 2001 09

of the winning tribe were protected from expulsion by “immunity” and thus remained eligible for the show’s prize

money. As in

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Big Brother, these cast-aways were competing for money (slightly over $1 ,OOO,OOO), most of which ($1,000,000) would be awarded to the sole “surviving” person.

The commercial success of Survivor has been well documented (Peyser, 2000). Just under 330 million viewers tuned in to the 13 episodes, including approximately 40 million for the final episode. Ten of the 13 episodes captured the top spot in the Nielsen ratings, and each of the last several episodes cap- tured a larger audience for CBS than that for the five other networks com- bined (Peyser). Advertisements for the final episode sold for $600,000 each, and the episode was estimated to have earned as much as $17 million (Peyser). Given that so many college-aged adults were watching, can we use this cultural phenomenon to convey certain econom-

ic lessons?

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Cartels and Castaways

In Table 1, I depict the “tribal coun- cil” voting history (across the 13 televi- sion episodes) from the 2000 edition of

Survivor. The castaways evicted from

the island, in order of eviction, are list- ed across the top of Table 1, and the list of voters forms the lefthand column of Table 1. Table 1 requires some explana- tion. For example, the Tagi tribe lost the immunity challenge in the first episode (which aired 5/31/00), and all Tagi members were therefore required to vote one Tagi member off the island at the tribal council. Sonja, the loser, received four (secret) votes from Rudy, Sue, Sean, and Dirk.4 Sonja, therefore, was required to leave the island. This process continued until two castaways remained. The winner was then chosen by a jury consisting of the final seven castaways expelled from the island.

Beginning in Episode

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

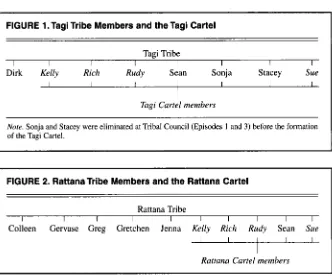

5 (airing on6/28/00), Rich led the formation of a coalition or “alliance” among himself, Sue, Rudy, and Kelly-all members of the Tagi tribe and the eventual final four contestants remaining on the island at the time of the show’s final episode (Figure 1 lists, in alphabetical order, the

members of the Tagi tribe at the show’s outset and the members of the Tagi car- tel). They reasoned that an alliance would enhance their individual chances of reaching the final group of four on the island, which would place each of them on the show’s final (13th) episode. Additionally, two of them would be assured of winning the first- and sec- ond-place prizes. Because the Tagi tribe lost the immunity challenge in episode

5, they agreed to cast their secret votes for Dirk.

Economics principles (Mankiw, 1998; Parkin, 2000) and intermediate economics texts (Perloff, 1999; Varian, 1999) often discuss the instability of cartel organizations in chapters cover- ing oligopoly/game t h e ~ r y . ~ For instance, Mankiw wrote that “some- times squabbling among cartel mem-

bers

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

...

makes agreement among themimpossible” (Mankiw, 1998, p. 341). Varian (1 999) concentrated on the cheating aspect of instability:

The problem with agreeing to join a car-

tel in real life is that there

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

is always atemptation to cheat..

. .

The firms need away to detect and punish cheating. If they have no way to observe each other’s out-

put, the temptation to cheat may break the

cartel. (Varian, 1999, pp. 484-485)

These passages are useful because they can be related to cartel behavior of both oligopoly firms and Survivor island contestants. The “temptation” described above results from the fact that individ- ual outcomes are often more important to cartel members than group results. As such, the larger individual profits that result from cheating by individual cartel members (in business) often lead to individual cheating and lower joint profits for the cartel, especially when detection and punishment of cheating are difficult or costly. With the cast- aways, the secret ballot process made it difficult to detect defections from the voting cartel. Additionally, it may also be difficult to identify any gains from cartel defections. Any purely selfish gain from defecting appears to be absent. This might explain periods of Tagi cartel stability. However, to illus- trate how strong incentives to cheat can be, one must also recognize that, with the castaways on Survivor island, indi- vidual decisions that result in larger

group rewards often may conflict with personal morals and convictions. For example, this carteualliance necessitat- ed lying (by cartel members) to other noncartel tribe members and to the show’s host, Jeff Probst, who often interviewed tribal voters at tribal coun- cil meetings. Sensing the formation of an alliance, Probst asked both Rich and Sue about their possible participation in such a scheme. Both denied any involvement. According to Rich (during a postshow interview), “I’m not sorry

for trying to build an alliance

.

. . I’m not sorry for blatantly lying [about my involvement with an alliance] to Jeff [Probst] at the tribal councils (Peyser, 2000, p. 54).”6 Kelly, on the other hand, seemed to have a more difficult decision each week at the tribal council. Kelly stated the following:I think it’s more important to be who you are and think for yourself than to have a

safety net with an alliance. I mean, it’s

only money

....

I thought it was going to be more strictly survival-oriented as opposed to people playing mind games. Itjust made me feel crappy about myself.

(Peyser, 2000, pp. 56-57)

Kelly’s feelings of remorse grew stronger after Episode 6 , when the

remaining members of the Tagi and Pagong tribes were merged (by CBS) to form a new tribe called Rattana (Figure 2 lists, in alphabetical order, the mem- bers of the Rattana tribe and the mem- bers of the Rattana cartel). After the merger, immunity and reward chal- lenges became individual contests, and immunity (reward) was granted to the individual castaway who was victorious in the immunity (reward) challenges. During Episodes 7-9, Kelly developed strong friendship bonds with two former Pagong members, Colleen and Jenna. Within the first two tribal councils after the merger, the cartel (alliance) contin- ued to stick together in voting for Gretchen and Greg, the two castaways voted off the island in Episodes 7 and 8.

In Episode 9, Rich, the cartel’s leader, targeted Jenna. It is here that Kelly first broke with the alliance by voting for Sean, who was not a cartel member.’

Kelly rejoined the alliance on Episode 10 by voting for Gervase but defected again on Episode 11 when the other cartel members had targeted her

90 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessTABLE 1. Tribal Council Voting History

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(by Episode)zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Voted ofPSONJA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

B.B. STACEY RAMONA DIRK JOEL GRETCHEN GREG JENNA GERVASE COLLEEN SEAN SUE RUDY 4 6 5 4 4 4 4 6 4 5 4 4 3 1Votersb E l E2 E3 El E5 E6 E7 E8 E9 E l 0 E l 1 E l 2 E l 3 E l 3

RICHARD Stacey

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

P-, RI

KELLY Rudy

[T, Rl

RUDY Sonja

[T, R1

SUE Sonja

[T, RI

SEAN Sonja

[T, RI COLLEEN

F, RI GERVASE

F,

RI JENNA [P> RI GREGF,

RI GRETCHENF,

RI JOEL [PIDIRK Sonja

[TI

RAMONA [PI

STACEY Rudy

[TI

B.B.

Fl

SONJA Rudy [TI

B.B. B.B. B.B. Ramona

BIB. B.B. B.B. Ramona

Stacey Rudy Stacey Stacey Stacey

Ramona Colleen Ramona Jenna Ramona Ramona Stacey

C o 11 e e n

Rudy

Dirk Dirk Dirk Dirk Rudy

Joel Jenna

Joel Joel Joel Jenna Sue

Gretchen Gretchen Gretchen Gretchen Colleen Richard Sue Gervase

JennaC Rudy

Greg Jenna Greg Sean Greg Jenna Greg Jenna Greg Jenna Jenna Richard Jenna‘ Richard‘ Greg Richard Jenna

Gervase Colleen Sean Sue

Gervase Sean‘ Sean‘ Sue’ Rudy‘ Gervase‘ Colleen Sean Sue

Gervase Colleen Sean Gervase Colleen Sue

Sean Sean Sean

aThe numbers below each name in the “voted off’ columns represent the number of votes the losing participant received at each tribal council. The episodes (e.g., El, E2) are listed below the losing partici- pants‘ vote totals. bTnbe abbreviations (listed below each voter): T = Tagi: P = Pagong: R = Rattana. ‘Denotes vote cast by a contestanthoter holding “immunity” (as such, they cannot be voted against).

FIGURE 1. Tagi Tribe Members and the Tagi Cartel

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Tagi Tribe

I I I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I I I I IDirk

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Kelly Rich Rudy Sean Sonja Stacey SueI

Tagi Cartel members

I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Note. Sonja and Stacey were eliminated at Tribal Council (Episodes 1 and 3) before the formation of the Tagi Cartel.

I I

FIGURE 2. Rattana Tribe Members and the Rattana Cartel

Rattana Tribe

---I ~ I I I 1 I I I I I

Colleen Gervase Greg Gretchen Jenna Kelly Rich Rudy Sean Sue

I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I

Rattana Cartel members

I

friend Colleen. It is interesting to note that by episode 1 1 the other cartel mem- bers (Rich, Sue, and Rudy) recognized that they needed to expel their defecting member (Kelly) but were prevented from doing so throughout the remainder of the series because Kelly emerged vic- torious from each successive immunity challenge. One irony is that Kelly’s immunity challenge victory in Episode 1 1 sealed the fate of her friend Colleen.

Selecting Reliables

Postshow interviews have focused a great deal on Rich’s analytical prowess and his ability to play the game. In inter- views with The Early Show’s Bryant Gumbel, Rich pointed out his recogni- tion of the need to form an alliance as early as possible.8 This, he suggested, necessitated selecting reliable partners. As Frank (1987) pointed out, commit- ment devices are essential when form- ing partnerships. One such commitment device, according to Frank (1987), is a conscience. A person with an overriding conscience will honor commitments/ promises even if material incentives favor breaking them. It is precisely this capacity of emotional forces to override rational calculations that makes them candidates for commitment devices. Of course, merely having a conscience does not solve the commitment prob-

lem; one’s potential trading partners must also know about it (Frank, 1987, p.

595). Physical symptoms (e.g., clues to deceit) and personal traits help identify such potential reliables. Such traits led Rich to select Rudy very early. Rudy, being a 72-year old retired Navy Seal, allowed Rich to surmise that honor and integrity would be overriding concerns in most decisions Rudy would contem- plate.’ Many times, both on the island and in postexpulsion interviews, Rudy was questioned about his loyalty to Rich. His answer almost always involved phrases such as “I gave my word, and I never go back on my word,”

or “My word is my bond.” These per- sonal traits became useful to Rich as the days passed on the island.I0

The personal traits of Sue and Kelly also aided Rich in selecting them for inclusion in the cartel. Sue often exhib- ited physical symptoms of lying (see Frank, p. 1987), which were evident to others. According to Sue, “I thought I lied awful. When Jeff [Probst] asked me about the alliance the first time, I looked like a deer caught in

.

. .

headlights” (Peyser, 2000, p. 59). In one instance, Sue made a secret subcartel pact with Kelly only to recant and confess this transgression to Rich. Rich used this information to solidify his commitment with Rudy to form a subcartel between the two.According to Frank (1987, p. 602), concerns about fairness often play an important role in the utility function. Sometimes people walk away from profitable opportunities because they would feel worse if they did not. These personal traits and utility considerations exhibited by both Kelly and Sue in many of the above passages were useful to Rich in forming two separate cartels and maintaining, to some degree, their cohesion.

To Join or Not To Join?

At least two additional cartel plots unfolded on Survivor Island during the 13-week production. These involved decisions made by Gretchen and Sean. Consistent with the explanations of Frank (1987), Sean seemed to exhibit the need to (a) play “fair,” and (b) be seedviewed as playing fair by all of the other castaways. To these ends he chose an “alphabet system” of voting in the tribal council meetings (beginning with Episode 7 through Episode 9; see Table

l), and he made a public pronouncement

of his voting strategy. In postexpulsion interviews, Sean defended his voting strategy, stating, “The proof of the pud- ding is that I never won [individual] immunity, I didn’t ally with anybody

and I beat out everybody else except the alliance” (Peyser, 2000, p. 59).

The question for principles and inter- mediate economics students revolves around whether Sean actually was at least a de-facto cartel member and whether he was allowed to survive by Rich’s cartel. By the second round of Sean’s alphabetical voting (Episode 8; see Table l), Rich’s cartel began to use Sean’s system to their own advantage by voting for Sean’s alphabetical target. This cartel strategy helped insulate its leader, Rich, against possible defec- tions.” During Episodes 8 and 9 (see Table 1), this cartel strategy helped expel Greg and Jenna, despite Kelly’s defection from the cartel in Episode 9. Sean’s feelings of remorse (see Frank, 1987) after Jenna’s expulsion led to his abandonment of this strategy. In any event, Sean’s announcement of this strategy made him a de-facto cartel member. His need to be seen as fair, based on aspects about his utility func-

92 Journal of Education for Business

[image:5.612.54.386.22.299.2]tion, made him a reliable de-facto cartel

member to Rich, the eventual

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Survivorwinner. These points help students understand that cartel (in)stability depends, in part, on the extent of non- cartel competition (Perloff, 1999). Rich’s voting cartel developed an inter- esting method for dealing with some of the noncartel competition (i.e,, Sean) on

Survivor Island.

The second plot involved Gretchen. Upon being told about the impending tribal merger, Colleen, Gervase, Jenna, and Greg-all Pagong members- agreed to form a “Pagong alliance” within the new Rattana tribe. When they approached Gretchen with this idea, she refused. Had she agreed instead, their alliance would have been (a) equal in size to the remaining Tagi tribe and (b) larger than the Tagi alliance (Rich, Sue, Kelly, and Rudy). However, after Gretchen’s refusal, the other Pagong members failed to solidify a cartel among themselves. Instead, during Rat- tana’s (the combined tribe’s name) first tribal council vote, each of these five cast votes for different contestants, and two votes were cast against (former) Pagong members (see Table 1, Episode 7). On the other hand, Rich’s cartel sin- gled out Gretchen for expulsion and was successful. The larger irony here is that Gretchen was the sole member of Pagong to refuse to form an alliance within the larger Rattana tribe, which, if successful, would have offered her pro- tection; instead, she was the first merged tribal member to be expelled. Secondly, Gretchen, a former instructor at the Air Force Survival School, was polled as the most likely winner by CBS. It is useful to point out to students that “economics skills” often supersede

“survival skills” in an effort to “Outwit

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

. .

.

Outplay. . .

Outlast.” Perhaps this understanding led Rich to make an “on camera” proclamation that he would emerge victorious during the 1st day onthe island.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Lessons Learned: Synthesis and Integration

The lessons learned from the 2000 edition of CBS’s Survivor series are many, and they are consistent with text- book treatment of cartel theory in eco-

nomics. First, cartels are inherently unstable organizations, usually because of individual incentives to defect (or cheat) on cartel agreements. These incentives are only strengthened when

output is unobserved

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(as with voting)and detection of cheating is thus costly. The fragile commitments to the Tagi cartel by Kelly, and to a lesser extent by Sue, only highlight these ideas. Second, because of these obstacles, the forma- tion of cartel partnerships require sub- stantive commitment devices. Accord- ing to Frank (1987), one such device is a conscience and/or concerns about the fairness of potential outcomes. Of course, one’s potential partners must be able to detect these concerns before they can be used as commitment devices. Physical symptoms and personal traits aid in this regard and significantly enhanced Rich’s ability to pick cartel partners and ultimately win the game (and $1,000,000). To these, ancillary lessons were added through the Sur- vivor series, such as the need to mini- mize the threat from noncartel competi- tion and the efficacy of threats of violence in enforcing cartel agreements. These lessons are evident from the car- tel’s use of Sean’s public voting strategy and Rudy’s veiled threats toward sus- pected cartel cheaters. These lessons are also paralleled in the commercial arena by OPEC’s holdings of much of the world’s oil reserves and by threats from New York City’s Italian bakeries to enforce cartel pricing (see Perloff, 1999).

Of course, integrating the Survivor lessons, which may be time consuming, into classroom discussions can prove problematic. Here are some suggestions for doing so. First, in my own principles classes, relatively little time is devoted to cartel theory in the traditional areas- the monopoly and oligopoly sections. However, I do spend some time cover- ing the game theory chapter in both the principles of microeconomics and inter- mediate microeconomics courses that I teach. Here, along with the familiar “prisoner’s dilemma,” I spend most of my effort discussing cartel (in)stability and incentives to cheat. As such, I can easily remove older examples and replace them with more timely and intu- itive examples (from the students’ per-

spectives) such as the cartel story from

Survivor Island. The examples should

prove useful to instructors who also fol- low this pattern. If not, this cartel story can be introduced in traditional sections (monopoly/oligopoly) by those who spend less time covering the game theo- ry portions of the text (principledinter- mediate).

The real value of the Survivor lessons may be their ability to be integrated into (a) undergraduate game theory courses, (b) undergraduate industrial organiza- tion courses, and (c) graduate (MBA- level) managerial economics courses. Here, the instructor generally has more time to devote to anecdotes that rein- force the textbook treatment of topics. In each of these three courses, monopoly and oligopoly models require significant portions of the semester, thus offering instructors ample opportunity to once again substitute more timely and intu- itive economics examples for traditional textbook treatments and examples.

Concluding Comments

Toward the end of the series, holding together the cartel consumed hours of time and normal daily activities for each of the four original cartel members. Each member kept constant vigil over the others’ interactions with cartel and noncartel participants alike. In a tradi- tional business setting, such policing efforts would have consumed resources that otherwise could have been devoted to production. All of the cartel-like activities that took place on Survivor Island-many of which have been detailed above-offer useful supple- ments to other methods of teaching this important aspect of microeconomic the- ory (see Caudill & Mixon, 1994). The fact that use of these examples inte- grates popular culture, which is familiar to most students, only heightens their value.

NOTES

I . The Real World involves young strangers

brought together as roommates who live and inter- act in front of television cameras. Road Rules

involves young strangers who live together (in front of television cameras) in a recreational vehi- cle. In this format, the young adults travel from locale to locale and perform “missions” (e.g., ath- letic contests, mental challenges, etc.) against each other or other contestants. In its 2000 ver-

Novernber/Decernber 2001 93

sion, MTV introduced a monetary reward system for its Road Rules contestants.

2. Big Brother usually aired 4 nights each week (on CBS) and in 30-minute edited episodes, although the general public could view live cam- era feeds via the Internet (<www.bigbroth- er2000.com>) at any time of the day. Every 2 weeks, each roommate nominated two other roommates to he “voted out of the house. The two roommates with the most nominations were then “marked for banishment.” and the general public decided which roommate was “banished” by participating in a phone poll. The phone poll spanned the course of the full week between roommate nominations and the banishment announcement. The entire show spanned approxi-

mately

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3.5 months. The last remaining roommate was awarded $500.000.3.The Summer 2000 version was filmed on Pulau Tiga in the South China Sea. Thirteen edit- ed television episodes appeared on CBS in the spring and summer of 2000. The two original tribes were named Tagi and Pagong, each com- prising teams of eight “castaways.” After the first six episodes, the remaining 10 members of the two tribes merged to form a tribe called “Rattana.” After the merger, the game was played, by partic- ipants, on an individual (as opposed to a team) basis. This is explored in more detail later in the article.

4. Sonja. like all castaways, was able to dis- cover the voting outcomes only upon departing from the island. All castaways were discouraged by CBS from disclosing information regarding the winner of the contest by signing $4 million liabil- ity contracts.

5.The main difference between the Tagi alliance and business enterprises ( e g , OPEC members) is that the Tagi members are not pro- ducing and selling a tangible product. However, other writers have described cartel behavior in

nonmarket settings (Caudill

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Mixon, 1994; Fleisher, Goff, & Tollison, 1992), including vote-producing congressional alliances (Mixon &

Ressler, 2000).

6. Rich often pointed out in postshow televi- sion and print interviews that the show’s produc- ers created the theme “Outwit . . . Outplay

. . .

Outlast.” According to Rich, this gave contestants a rationale for strategy and forming allianceskar- tels.7. The remaining three cartel members-Rich, Sue, and Rudy-had some indication that one of their members had defected because (a) Jenna, that week’s loser, received only four total votes, and (b) Sean had previously announced an alphabetical system for tribal council voting and he pronounced that Jenna was next on his alphabetical list.

8. The success of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Survivor spilled over to TheEarly Show. On Thursdays, when every “sur- vivor” (except Greg) appeared on The Early Show for his or her first postexpulsion interview, ratings for The Early Show were up over 25% (compared with 1999 ratings). Additionally, the median age of CBS’s prime time audience dropped 4 years since Survivor debuted (Peyser, 2000, p. 59).

9. These traits were so important to Rich that he concluded a subpact with Rudy to form a sec- ond cartel between the two should the final four be represented by the original four cartel members. Rich’s ability to coordinate the formation of the two cartels and select reliables is suggested by his background. He (39 years old) had spent most of his career as a corporate trainer, conducting semi- nars on conflict management, team building, prac- tical negotiation, and public speaking (<www.cbs.coms).

10. Rudy also directed veiled threats to the other cartel members while they were on the island. Many of these were threats of physical harm toward any potential defectors. These threats included statements similar to “I know people on the outside” or “I’ve got friends back home who’ll ‘take care’ of double-crossers.” These are interest- ing devices for forcing commitment to cartel deci- sions. Perloff (1999, pp. 427-428) detailed the use of threats of violence by Italian bakers in New York City (early 1990s) to enforce cartel pricing in that market.

11. It also would not have been unreasonable for Rich to assume that Sean’s pronouncements would lead to retaliatory votes against Sean by his own alphabetical target. Had this occurred, it would have offered further protection to Rich and his cartel cohorts. Examination of the information

in Table

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1, however, reveals that this did not occur.ACKNOWLEDGMENT

1 would like to thank an anonymous referee, Mark Dickie, and Charles Sawyer for their helpful comments.

REFERENCES

Becker, W. E., & Watts, M. (1995). Teaching

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

tools: Teaching methods in undergraduate eco-

nomics. Economic Inquiry, SJ(0ctober). Becker, W. E., & Wattas, M. (1998). Teaching eco-

nomics to undergraduates: Alternatives to chalk and talk. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. Caudill, S. B., & Mixon, F. G., Jr. (1994). Cartels and the incentive to cheat: Evidence from the classroom Journal of Economic Education, 25(Summer), 267-269.

Fleisher, A. A,, 111, Goff, B. L., & Tollison, R. D.

( 1992). The National Collegiate Athletic Asso-

ciation: A study in cariel behavior. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Frank, R. H. (1987). If Homo Economicus could choose his own utility function, would he want one with a conscience? American Economic

Review, 77(September), 593-604.

Kish-Goodling, D. M. (1998). Using the Merchant

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Venice in teaching monetary economics.

Journal of Economic Education, 29(FaII), 330-339.

Mankiw, N. G. (1998). Principles of economics. New York: Dryden.

Mixon, F. G., Jr., & Ressler, R. W. (2001). Loyal political cartels and committee assignments in Congress: Evidence from the Congression- al Black Caucus. Public Choice, 108, Parkin, M. (2000). Economics. Reading, MA:

Addison Wesley Longman.

Perloff, J. M. (1999). Microeconomics. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Peyser, M. (2000, August 28). Survivor tsunami.

Newsweek. pp. 52-59.

Tinati, F. D., & Khandke,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

K. (2000). From rhythm and blues to Broadway: Using music to teacheconomics. Journal of Economic Education,

3I(Summer), 253-270.

Trandel, G. A. (1999). Using a TV game show to explain the concept of a dominant strategy.

Journal of Economic Education, 30(Spring),

Varian, H. R. (1999). Intermediate microeconom-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ics: A modern approach. New York: Norton. Watts, M., & Smith, R.E. (1989). Economics in

literature and drama. Journal of Economic Edu- cation, ZO(Summer), 291-307.

692-700. 3 13-330. 133-140.