i

SEA-Immun-114 Distribution: General

Joint National/International Expanded

Programme on Immunization and

Vaccine Preventable Disease

Surveillance Review

Republic of the Union of Myanmar

ii

Joint National/International Expanded Programme on Immunization and Vaccine Preventable Disease Surveillance Review, Republic of the Union of Myanmar, 25 September – 8 October 2016 (SEA-Immun-114)

© World Health Organization 2017

Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo).

Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”.

Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Suggested citation.: Joint National/International Expanded Programme on Immunization and Vaccine Preventable Disease Surveillance Review, Republic of the Union of Myanmar. [New Delhi]: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia; [2016]. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris.

Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders. To submit requests for commercial use and queries on rights and licensing, see http://www.who.int/about/licensing.

Third-party materials. If you wish to reuse material from this work that is attributed to a third party, such as tables, figures or images, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that reuse and to obtain permission from the copyright holder. The risk of claims resulting from infringement of any third-party-owned component in the work rests solely with the user.

General disclaimers. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WHO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

iii

interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall WHO be liable for damages arising from its use.

TABLE OF CONTENT

ACRONYMS ... I ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... IV

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ... - 1 -

INTRODUCTION ... 10

BACKGROUND ... 12

REVIEW OBJECTIVES ... 21

METHODOLOGY ... 22

LIMITATIONS ... 23

FINDINGS AND KEY RECOMMENDATIONS BY TOPIC AREA ... 24

GENERAL ... 24

GOVERNMENT SUPPORT ... 24

PROGRESS IN MEETING GLOBAL AND REGIONAL GOALS. ... 46

NUVI ... 60

CONCLUSION ... 63

ANNEXES ... 64

ANNEX 1. LIST OF PARTICIPANTS IN JOINT NATIONAL/INTERNATIONAL EPI REVIEW ... 64

ANNEX 2. AFP SURVEILLANCE INDICATORS,MYANMAR,2016 AS OF WEEK 42 ... 67

ANNEX 3. QUALITY OF MEASLES PERFORMANCE INDICATORS,MYANMAR,2011-2015 ... 68

iv

List of Tables

TABLE 1.EPI SCHEDULE,MYANMAR,2016 --- 17

TABLE 2.FINANCIAL INDICATORS REPORTED TO WHO,MYANMAR,2013-2015(ALL FUND AMOUNTS IN US$) --- 18

TABLE 3.VACCINATION COVERAGE:WHO AND UNICEF BEST ESTIMATES AND COUNTRY ESTIMATES.MYANMAR, 2012-2015. --- 19

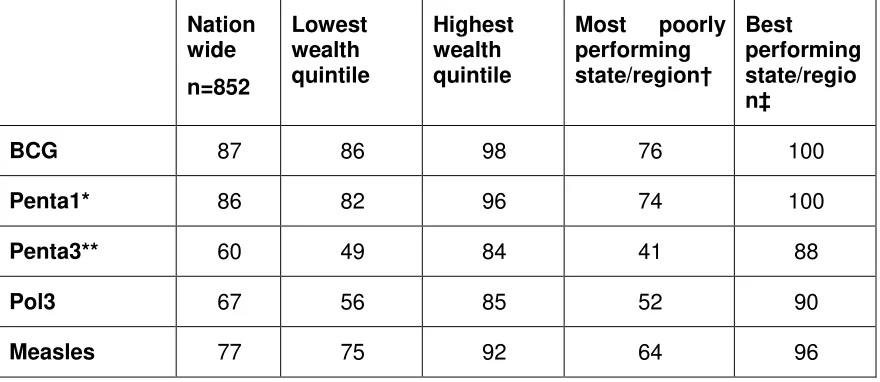

TABLE 4.DHS ESTIMATES OF VACCINATION COVERAGE.MYANMAR,2015-2016 --- 20

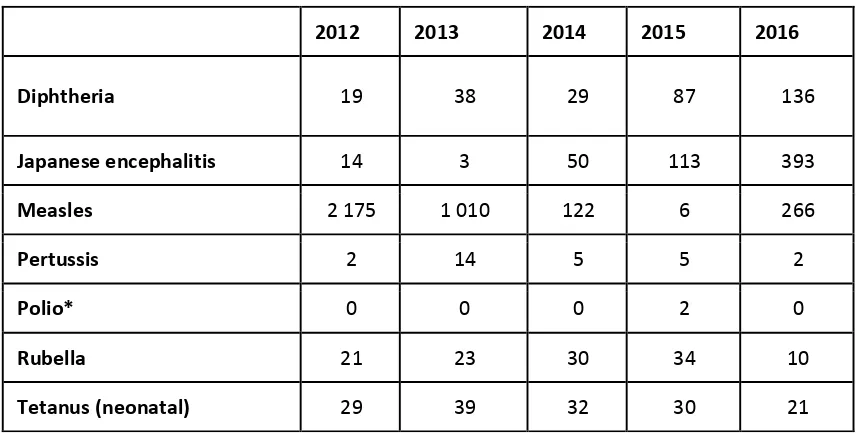

TABLE 5.VPDS REPORTED TO WHO,2013–2016 --- 21

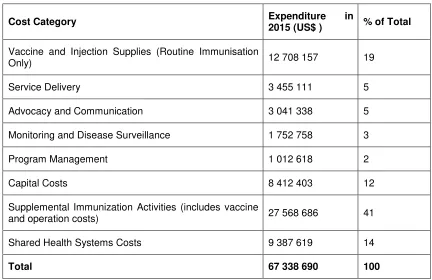

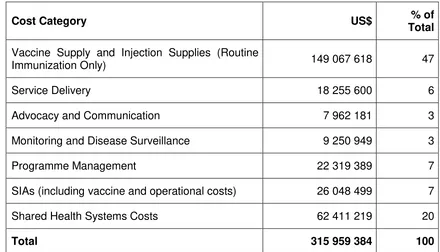

TABLE 6.BASELINE COST PROFILE OF IMMUNIZATION PROGRAMME IN 2015 --- 26

TABLE 7.FUTURE IMMUNIZATION PROGRAMME RESOURCE REQUIREMENTS,2017-2021--- 27

TABLE 8.SOURCES OF EPIVACCINE FUNDING IN MYANMAR AS OF AUGUST 2016 --- 33

TABLE 9.AFP AND FEVER/RASH SURVEILLANCE INDICATORS,MYANMAR,2012-2015 --- 43

List of Figures

FIGURE 1.MAP OF MYANMAR ... 12FIGURE 2.ORGANOGRAM OF THE MOHS,MYANMAR... 14

FIGURE 3.ORGANOGRAM OF THE DOPH,MYANMAR ... 14

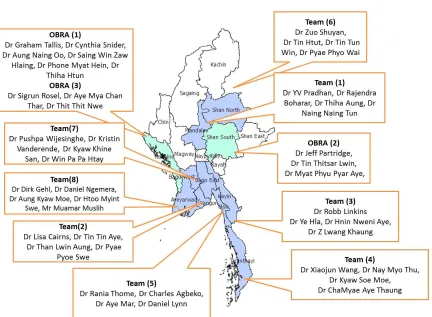

FIGURE 4.MAP OF MYANMAR SHOWING SITES VISITED BY THE REVIEW TEAM ... 23

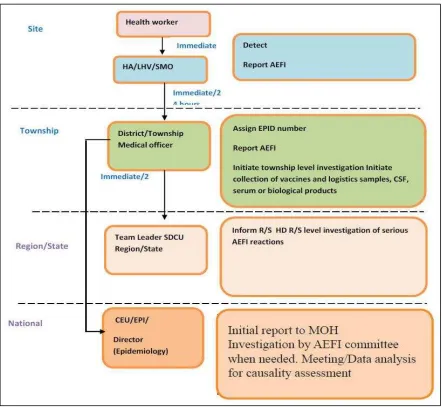

FIGURE 5.REPORT ROUTING, TIMELINE AND MANDATED ACTIONS FOR AEFI ... 31

FIGURE 6.REPORTED SERIOUS AEFI CASES,MYANMAR,2007-2015 ... 32

FIGURE 7.PERFORMANCE OF ISC IN MYANMAR ... 34

FIGURE 8.INTEGRATED WEEKLY VPD REPORTING ... 42

FIGURE 9.FIRST AND SECOND DOSE COVERAGE OF MCV,SIAS, AND CASE AND DEATH COUNT,MYANMAR,1987– MID -2016 ... 51

FIGURE 10.PERCENTAGE OF TOWNSHIPS WITH AT EAST 95% COVERAGE WITH MCV1, BY YEAR.MYANMAR,2010-2015. 51 FIGURE 11.SEROPREVALENCE OF CHRONIC HBV INFECTION IN 18 TOWNSHIPS ... 54

i

A

CRONYMS3MDG Three Millennium Development Goal Fund AEFI adverse events following immunization AES acute encephalitis syndrome

AFP acute flaccid paralysis BCG Bacille Calmette Guerin bOPV bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine

CEPI Central Expanded Programme on Immunization CEU Central Epidemiology Unit

CIF case investigation form

cMYP comprehensive multi-year plan CRS congenital rubella syndrome CTC controlled temperature chain

cVDPV circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus cVDPV2 type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus DG Director General (of Public Health) DHS Demographic Health Survey DoPH Department of Public Health

DoV Decade of Vaccines

DTP diphtheria–tetanus-pertussis

EPI Expanded Programme on Immunization EVM Effective Vaccine Management

GAPIII third edition of the Global Action Plan to minimize post-eradication poliovirus facility-associated risk

Gavi Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance GDP gross domestic product GNI gross national income GVAP Global Vaccine Action Plan GSP good supply practices HBV hepatitis B virus

HCW health care worker

HBeAg hepatitis B e antigen HBsAg hepatitis B surface antigen HepB hepatitis B vaccine

ii

Hib Haemophilus influenzae type B HPV human papilloma virus

HSS2 second health system strengthening grant (from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance)

IEC information, education and communication INGO international nongovernmental organization IPAC Immunization Practices Advisory Committee IPV inactivated poliovirus vaccine

iSC immunization supply chain

JCV Japan Committee "Vaccines for the World's Children" JE Japanese encephalitis

M single antigen measles vaccine

M2 second dose of single antigen measles vaccine MCV measles antigen containing vaccine

MCV1 first dose of measles antigen containing vaccine MCV2 second dose of measles antigen containing vaccine MNTE maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination

MoHS Ministry of Health and MoPF Ministry of Planning and MR measles-rubella vaccine (MR)

MR1 first dose of measles–rubella vaccine MR2 second dose of measles-rubella vaccine

MW midwife

Myanmar the Republic of the Union of Myanmar

NCCPE National Certification Commission for Polio Eradication NCIP National Committee for Immunization Practices

NGO non-governmental organization NHL National Health Laboratory NHP National Health Plan

NPERC National Polio Expert Review Committee

NPLCC National Polio Laboratory Containment Committee NRA National Regulatory Authority

NT neonatal tetanus

NUVI new and underutilized vaccine introduction

iii

OBRA (poliovirus) outbreak response assessment OPV oral polio vaccine

OPV3 third dose of oral polio vaccine P1 poliovirus type 1

P2 poliovirus type 2

PCV pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

Penta pentavalent vaccine (diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus-hepatitis B-Haemophilus influenzae type B)

Pol3 third dose of polio vaccine (either oral or inactivated) PV2 Poliovirus type 2

RCV1 first dose of rubella antigen containing vaccine RHC rural health centre

RHSC rural health sub-centre RSO regional surveillance officer

SEAR World Health Organization South-East Asia Region

SEAR ITAG South-East Asia Regional Technical Advisory Group on Immunization

SEARVAP South-East Asia Region Vaccine Action Plan SIA supplementary immunization activity

SOP standard operating procedure THE total health expenditure

tOPV trivalent oral poliovirus vaccine

TT tetanus toxoid

TT2 second dose of tetanus toxoid UHC universal health care

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

US CDC United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention VDPV vaccine-derived poliovirus

VDPV2 type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus VII Vaccine Independence Initiative VPD vaccine preventable disease VVM vaccine vial monitor

WPV wild poliovirus

WHO World Health Organization

iv

A

CKNOWLEDGEMENTS- 1 -

E

XECUTIVES

UMMARYBackground and Methodology

The Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (Myanmar) has achieved considerable success in preventing and controlling vaccine preventable diseases (VPD). The country has seen a recent increase in government commitment to EPI. Since 2015 (inclusive), Myanmar has successfully introduced four vaccines and intends to introduce three more by end-2019. However, the country faces new challenges as it is forecast to transition from eligibility for funding from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi) and must self-finance all vaccines by 2025. Furthermore, as the country seeks to reach every child with vaccine, it faces unique sociocultural and political challenges.

As part of systematic reviews scheduled to be carried out in all World Health Organization (WHO) South-East Asia Region (SEAR) countries, WHO’s Regional Office for South-East Asia and Myanmar’s Ministry of Health and Sport (MoHS) collaborated to conduct a Joint National/International EPI and VPD Surveillance Review in Myanmar from 25 September to 08 October 2016. In 2015, Myanmar had also experienced an outbreak of circulating type 2 vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV2), to which the country responded in accordance with WHO guidelines. This response was assessed concurrently with the EPI and VPD Surveillance Review; the results of the assessment are reported elsewhere.1

The objectives of Myanmar’s Review were to:

Understand which children in Myanmar are not being fully immunized and the reasons that this is occurring. To the extent possible, efforts were made to assess areas with limited access to government services and increased reliance on other providers such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) or local administrations; Determine if the VPD surveillance system meets national and global targets and is

currently able to detect any VPD outbreaks; this would include laboratory support and data management systems;

Determine if the strategies being implemented for measles and rubella objectives are adequate to maintain or achieve targets;

Assess how strategies and capacities of the immunization programme need to be strengthened to sustain polio-free status and maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination (MNTE), accelerate hepatitis B control and uniformly increase coverage for all routine vaccines; this would include vaccine and supply management,

1

WHO. Regional Office for South-East Asia. Immunization. Documents and Publications. External Second Assessment: Circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Type 2 (cVPDV2) Outbreak Response, Myanmar, 25 September-8 October 2016. Available at

- 2 -

adverse events following immunization (AEFI) management, financing and sustainability.

Myanmar’s Central Epidemiology Unit (CEPI), and WHO’s Regional Office for South-East Asia and Country Office in Myanmar collaborated to assemble a review team of Myanmar members drawn from national and state/regional levels as well as internationals representing a variety of agencies. The team conducted a desk review of relevant policies and guidelines; secondary analysis of available data; interviews with key stakeholders, policy makers, and programme staff; and direct observation of programme implementation at field sites throughout Myanmar.

Key Findings

Myanmar shows an increasing level of government support with increased funding in 2015 for EPI and the articulation of immunization as one of five health priorities in the

new government’s 100-day plan. Historically, Myanmar’s health budget has been low, both in absolute terms and as a proportion of gross domestic product (GDP); this has in turn been reflected in low government funding and a heavy dependency on external funding for the EPI. Recent growth in GDP has translated into an increasing health budget and a 2016 commitment to fund traditional vaccines and co-finance vaccines supported by Gavi.

The programme benefits from a number of advisory and oversight bodies, several chaired by the Director General (DG) of Public Health. Reporting of AEFI and response to AEFI has been adequate to detect and mitigate the impact of several major events in recent years. All vaccines used in the country must be licensed by Myanmar’s National Regulatory Authority (NRA). Vaccine is procured annually through the United Nations

Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The country underwent an Effective Vaccine Management

(EVM) review in 2015 and has developed an improvement plan, in the process of implementation, to respond to the findings of this review.2

Equitable and universal delivery of vaccination in Myanmar is challenged in several

- 3 -

by the second grant from Gavi for health system strengthening (HSS2) funding which will cover 2017 -2019.3

VPD surveillance is an integral part of the evaluation process to ensure that a country is delivering high quality vaccination services to the entire population. Elimination and eradication goals require that countries raise their surveillance standards and their use of surveillance data to levels beyond those needed for disease control alone. While VPD surveillance in Myanmar is strong enough to detect large outbreaks, its usefulness to the programme is hampered by limited sensitivity, resulting in part from inadequate health worker awareness of surveillance protocols and specimen collection for suspected cases, as well as by incomplete local ownership in terms of data analysis and use. In addition, it is possible that the country’s sociocultural and political diversity impact under-reporting of diseases. The National Health Laboratory (NHL) provides excellent support to the programme, but at times confronts challenges in terms of quality of specimens received and/or incomplete or no case investigation forms (CIF). Myanmar was certified polio-free on 27 March 2014 with all other countries in the region. The last case of indigenous wild poliovirus (WPV) was reported in 2000 and the last imported WPV was identified in 2007. However, the country has experienced cases of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV), with the most recent cases confirmed in 2015 in Rakhine State. Outbreak response assessments (OBRA) were carried out twice as per the requirements of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative; the second OBRA was conducted concurrently with this EPI and VPD surveillance review. Reports of both first and second assessment are available at:

http://www.searo.who.int/entity/immunization/documents/en/

The country achieved MNTE in 2010. Since that time, the country has made continuous efforts to maintain MNTE with a particular focus on ensuring that women receive at least two doses of tetanus toxoid (TT), conducting neonatal tetanus (NT) surveillance, and promoting the presence of skilled attendants at births.

Myanmar administers the first dose of measles containing vaccine (MCV1) at 9 months and the second dose (MCV2) at 18 months of age. MCV2 was introduced in 2012; in 2015, following a nationwide measles-rubella vaccine (MR) supplementary immunization activity (SIA) targeting those aged 9 months – 15 years and achieving a reported 94% coverage, Myanmar replaced single antigen measles vaccine (M) at 9 months with MR and plans to begin using MR as MCV2 in 2017. To achieve measles elimination, at least 95% coverage with two doses of MCV must be reached in 100% of districts. In 2015, only 19% of districts achieved at least 95% coverage with MCV1. Measles surveillance indicators suggest substantial surveillance gaps while there is relatively little awareness of rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS). Sentinel CRS surveillance is scheduled to begin in 2017.

3

- 4 -

Myanmar has intermediate to high hepatitis B endemicity. A major intervention to prevent mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B is administration of a dose of hepatitis B vaccine within 24 hours of birth (HepB-BD). Hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) was introduced in 2003, with HepB-BD supported by Gavi. The discontinuation of Gavi support for HepB-BD resulted in discontinuation of HepB-BD as part of EPI. HepB-BD will be (re)introduced in hospitals in the last quarter of 2016. However, reaching regional 2020 hepatitis B control goals will require expansion of the use of HepB-BD beyond hospitals.

Myanmar has a functional National Committee for Immunization Practices (NCIP) to guide decisions on new and underutilized vaccine introduction (NUVI). Since 2012 (inclusive), Myanmar has successfully introduced MR, inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine (bOPV) and pneumococcal vaccine (PCV) and plans to introduce Japanese encephalitis (JE) vaccine in 2017, rotavirus vaccine in 2018, and human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine in 2019. In terms of NUVI, a major challenge faced by Myanmar is expansion of sentinel surveillance sites and generation of burden of disease and economic data to adequately inform decision-making processes.

Key Recommendations

A. Government Support

Advocacy

Look for opportunities to advocate at the highest level (for example, Cabinet) for the EPI. Work with partners [US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), WHO and UNICEF] to develop a slide-set showcasing immunization as a ‘best-buy’ which can be used in advocacy.

Finance

Advocate at all levels and with all stakeholders for a comprehensive health financing policy in the context of the universal health care (UHC) vision for Myanmar as a pre-requisite for increasing health budget allocations.

Advocate for the CEPI to be an example of increasing national financial shares for essential public health services and of high return on investments in the health sector.

Operationalize the comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2017-2021 (cMYP) financing strategy options and explore innovative resource mobilization and financial instruments (for example, community participation, an immunization trust fund4, and efficiency gains in service delivery).

4

A detailed explanation of immunization trust funds is provided in Domestic trust funds. In Immunization financing: A resource guide for advocates, policymakers and program managers (website).

- 5 -

Reform and restructure financial management at the central and regional levels to allow effective utilization of available resources, including greater flexibility in funding allocation at peripheral levels and more rapid transfer of funds from central to peripheral level.

Oversight Bodies

Explore whether oversight and advisory bodies may wish to follow WHO ‘best practices’ by having chairmanship independent from government.

AEFI Surveillance

Develop stringent regulations requiring proper supply regulatory inspection for public and private sectors.

Allocate budget for enhancing AEFI surveillance. Vaccine Licensing, Procurement and Management

Accelerate the approval of the Vaccine Independence Initiative (VII) and initiate its implementation.

Accelerate the implementation of the EVM improvement plan with close monitoring of progress against established milestones and timelines.

Strengthen human resource support for the iSC and management in following ways:

Establish sanctioned posts for cold chain Key persons and supportive staff at all levels;

Redefine necessary qualifications and terms of reference for iSC and management posts particularly at the storage points where large quantities of vaccines are kept (central and state/region sub-depot);

Provide routine training to staff, as well as on-the-job coaching through supportive supervision.

Advocate for a national budget line to ensure stable and predictable funding for the iSC once Gavi’s HSS2 to Myanmar is ended.

Demand Generation

Implement and evaluate the impact of the communication activities defined in HSS2.

Conduct training at regional and township levels to improve interpersonal and risk communication skills among basic health staff and volunteers.

- 6 - Service Delivery

Short term

Implement HSS2.

Develop a quarterly implementation plan and set up a high-level mechanism of oversight (DG or Minister).

Mid/long term

Create national and state/regional-level government budget lines for EPI to cover both vaccine and operational costs (for example, field allowances for midwives (MWs), vaccine transportation, outbreak response, supervision and monitoring). Create positions and supportive funding for dedicated EPI staff (EPI and cold chain

key persons, data focal person) at state/region and township levels.

Allow flexibility and promote local approaches and language to encourage tailoring of service delivery to special populations.

B. VPD Surveillance

Focus Regional Surveillance Officer (RSO) responsibility on VPD surveillance and EPI.

Increase frequency of active VPD surveillance in large hospitals.

Provide VPD surveillance-specific refresher training to clinicians and health staff with a specific focus on case definitions, procedures for specimen collection and transport.

Increase laboratory confirmation and genotyping of cases.

Encourage calculation of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) and fever/rash surveillance indicators at subnational levels to increase ownership.

C. Progress in Meeting Global and Regional Goals

Polio

For recommendations related to polio, please see those contained in the report of the OBRA conducted from 25 September to 08 October 2016, available at

http://www.searo.who.int/entity/immunization/documents/en/

MNTE

In highest-risk communities incompletely reached through routine immunization, TT SIAs targeting women of child bearing age could be considered.

To improve the sensitivity of the existing case based NT surveillance system:

- 7 -

o strengthen the maternal and infant death reporting and auditing system and

investigate all reported infant deaths;

o establish a monitoring mechanism for community based surveillance,

comparable to that used for AFP surveillance;

o ensure that the NT case investigation form allows supervisors and

surveillance personnel at all levels to have a complete understanding of the history and symptoms of the case and to confirm diagnosis of the suspected NT case; and

o adapt the case response to the cause(s) of non-protection. If the mother

requires vaccination to protect further unborn children, other eligible women in the same community should also be evaluated for TT vaccination status and targeted for immunization based on eligibility.

To increase use of skilled delivery care in high-risk and hard-to-reach areas consider:

o strategic re-deployment of MWs to high-risk areas; and

o strategic deployment of lady health visitors to fill gaps in skilled birth

attendance.

To expand the types of providers able to administer TT vaccine consider:

o using auxiliary MWs as TT vaccinators to minimize missed opportunities for

TT protection; and

o in hard-to-reach areas, partnering with qualified private or NGO sector

providers with success and local acceptability operating in those contexts. To increase use of facility care by communities in close proximity to health centres,

consider:

o an incentive scheme (for example, conditional cash transfers) for

accessible communities; and

o vouchers for transport to rural health centres (RHCs).

Measles and Rubella

Increase commitment to measles and rubella elimination by:

o gaining agreement to 2020 rubella elimination goal once the second dose of

MR (MR2) is added to the routine immunization schedule; and

o finalizing the National Measles and Rubella Strategy, 2016-2020, ensuring it

reflects the rubella elimination goal.

Increase to at least 95% MCV2 coverage in all districts by:

o developing costed sub-national measles/rubella elimination work plans with

- 8 -

o conducting village-level risk assessment and mitigation;

o conducting school-based immunization record checks at school entry; and o conducting SIAs when the population immunity gap equals the size of the

birth cohort.

Move from “control” to “elimination” standard surveillance by:

o increasing surveillance sites beyond AFP sites to include all health facilities,

and train relevant staff;

o developing a clear implementation plan, with communication strategy, for

fever/rash surveillance, and a field guide with standard operating procedures (SOPs) with clear designation of roles and responsibilities for specimen collection and transport, and train relevant staff; and

o finalizing CRS guidelines and establishing CRS sentinel sites in 2017 as

planned.

Improve rapid outbreak control and response by:

o implementing hospital infection control;

o vaccinating high risk adults, including health care workers (HCW), at no

cost; and

o vaccinating at-risk populations, such as orphaned children cared for within

monasteries. Hepatitis B

Develop an immunization specific national hepatitis B operational plan to achieve the 2020 hepatitis B control goal and expand HepB-BD to reach deliveries that occur outside hospitals.

Explore using vaccine for HepB-BD outside the cold chain in RHCs, sub-centres, and home births. This would require using a single dose HepB-BD with vaccine vial monitors and approval by the National Immunization Technical Advisory Group and relevant national regulatory body.

Train HCW on birth dose storage, vaccination, and recording. NUVI

Develop a sustainable immunization financing plan and periodically update it to ensure predictable funding for sustaining routine immunization and NUVI.

- 9 -

Implement the cold chain improvement plan with the Gavi HSS2 to expand the cold chain capacity to accommodate JE, rotavirus and HPV vaccine introduction, as well as provide expansion of the cold chain to cover more service delivery points.

Conclusion

10

I

NTRODUCTIONThe Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (Myanmar) has achieved considerable success in preventing and controlling vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs). The country has seen a reduction of > 90% in cases of diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus when compared to the period prior to the implementation of the EPI in 1978. Myanmar achieved maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination (MNTE) in 2010 and was certified polio-free in 2014. Recent years have seen the successful introduction of measles-rubella vaccine (MR), inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine (bOPV) and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV). Reporting of the EPI target diseases (polio, measles, rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, neonatal tetanus (NT)) and Japanese encephalitis (JE) (for which the vaccine is not yet part of the country’s EPI) are mandatory and is based on clinical and/or laboratory evidence; reporting for some diseases is based on syndromic surveillance.

In spite of impressive decreases in the overall morbidity and mortality due to VPDs in Myanmar, gaps in coverage in certain populations have led to disease outbreaks. In 2012 and 2015, Myanmar experienced outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV). Sporadic cases of diphtheria, many based on clinical diagnosis, have been reported annually, with numbers varying from 19 to 87 in the past five years. Myanmar subscribes to the key strategic objectives of the Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) and the global goals of the Decade of Vaccines (DoV) (2011-2020)5 (1) achieve a world free of polio, (2) meet vaccination coverage targets, (3) reduce child mortality, (4) meet global and regional elimination targets, and (5) develop and introduce new vaccines. Myanmar also subscribes to regional goals of eliminating measles and controlling6 rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) by 2020, as well as accelerating the control of hepatitis B and JE. In line with the World Health Organization (WHO) South-East Asia Region (SEAR) Vaccine Action Plan (VAP), the country also seeks to strengthen routine immunization systems and services, and accelerate the introduction of new vaccines.7

The South-East Asia Regional Technical Advisory Group on Immunization (SEAR-ITAG) recommends that each country should conduct periodic joint national-international programme reviews in addition to its own regular internal programme monitoring. The last international EPI review in Myanmar was conducted in 2008.

5

Global Vaccine Action Plan. World Health Organization. 2013.

http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/en/ . Accessed 15 November 2016

6

Defined as a95% reduction of rubella and CRS as compared with the 2008 baseline nationally and for the Region

7

11

Joint national/international EPI reviews conducted in SEAR, including this one, have three broad objectives, which are to:

provide a snapshot to public health programme directors and public health policy makers on the status of the EPI and VPD surveillance;

assess progress in meeting key national, regional and global goals; and

provide an opportunity to share lessons learned with other countries which share the same goals for preventing and controlling VPDs.

12

B

ACKGROUNDGeneral

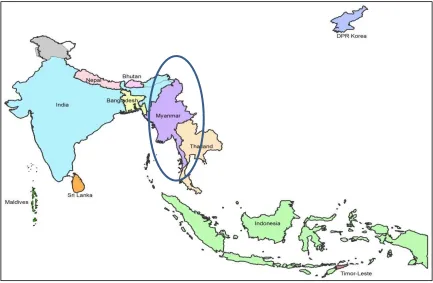

Myanmar, a South-East Asian country, shares boundaries with the People's Republic of Bangladesh, the Republic of India, and the People’s Republic of China, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and the Kingdom of Thailand. The country covers approximately 676 000 km2. It is administratively divided into one territory and 14 states or regions with a total of 74 districts.

Figure 1. Map of Myanmar

In 2014, the population of Myanmar was estimated at 51.5 million. Approximately 28% of the population was aged 0-14 years, 6% was aged more than 65 years and the median age in the country was 27.1 years. The population growth rate was 0.89% with a total fertility rate per woman of 2.29. Life expectancy at birth was 67 years. Under-five mortality per 1000 live births was 72. From 2008 to 2012, the male literacy percentage in those aged >15 years was 92.6% and the female literacy percentage for the same age group was 86.9%. Approximately 28% of households are urban.8 Myanmar has >130 ethnic groups speaking more than 100 languages and dialects. There are eight major

8

13

ethnic groups: Bamar, Shan, Kayin, Rakhine, Mon, Chin, Kachin and Kayah. Approximately 90% of the population is Buddhist, 5% is Christian, and 4% Muslim. Myanmar is considered a lower middle income country with a gross domestic product (GDP) in 2014 of US$ 64.33 billion and an annual GDP growth rate that year of 8.5%.9 In November 2015, general elections were held resulting in the National League for Democracy forming the national government. Priority areas within health for the government include the strengthening of the immunization programme and health information systems, standardization of working procedures across health sectors, the development of a code of ethics for all health personnel, fostering cooperation between private and public sectors, and responding to outbreaks in a timely and appropriate fashion.

Health Services and EPI in Myanmar

Health Services

In 1993, the National Health Policy was developed which places ‘Health for All’ as a

primary objective. The National Comprehensive Development Plan (Health Sector) covers the period from 2010/2011 to 2030/2031. Short-to-medium-term planning is provided through a series of five-year health plans, with the most recent covering the period from 2011/2012 to 2015/2016.10

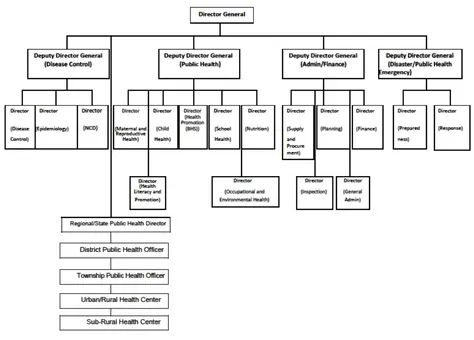

The Ministry of Health and Sport (MoHS), previously known as the Ministry of Health, is responsible for planning, financing, administrating, regulating and providing health care. The Department of Public Health (DoPH) is one of six departments within the Ministry, and is responsible for immunization which is managed by Central Expanded Programme on Immunization (CEPI) as well as disease surveillance activities; both of these fall under the Central Epidemiology Unit (CEU) (Figures 2 & 3).

9 The World Bank data base (online database). Washington: World Bank; 2016

(http://data.worldbank.org/country/myanmar, accessed 31 July 2016)

10

14 Figure 2. Organogram of the MoHS, Myanmar

Source: Ministry of Health Restructuring, 2015. Ministry of Health and Sport. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

Figure 3. Organogram of the DoPH, Myanmar

15

In Myanmar, both public and private sectors provide health care, with the private sector providing primarily ambulatory care. The strengthening of community-based health services is considered critical to improving health care in Myanmar. The importance of building national capacity in field epidemiology is also recognized and Myanmar participates in the Association of South-East Asian Nations Plus Three Field Epidemiology Training Network.11

EPI

The EPI was launched in Myanmar in 1978. Partner support for the EPI is received from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance (Gavi) (new vaccine introduction, cold chain expansion, health system strengthening), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (procurement of traditional vaccines, education and communication materials and cold chain expansion), WHO (surveillance, capacity building, review meetings, etc.) and the Three Millennium Development Goal Fund (3MDG)12 (operational support to targeted townships, cold chain support). The role of the local community, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)

and women’s organizations is limited to advocacy and social mobilization. A recent focus of immunization services has been the border and hard-to-reach areas which have displaced and vulnerable populations, as well as areas of previous conflict and peri-urban areas. Few NGOs work in these settings. Difficulties in reaching populations have been linked to inadequate staff for immunization; as a result, the MoHS plans to increase the number of staff trained to give vaccinations.13 The government which came to power in 2016 has articulated immunizations as being one of its top five health priorities.

A comprehensive multiyear plan (cMYP) for immunization covers 2017-2021. This plan has the following programme objectives:

To strengthen immunization programme management, human resources, financing and service delivery to provide equitable service to all target populations including special strategies for peri-urban, slum, migratory populations, geographically and socially hard- to-reach and conflict areas;

To improve demand creation and ownership of immunization through community participation and communication;

To strengthen immunization supply chain (iSC), vaccine management and build stronger cold chain systems at all levels;

To achieve the goals of eradication, elimination and control of VPDs: and

To maintain zero polio cases (both wild poliovirus (WPV) and VDPV);

11

Health in Myanmar. 2014. Ministry of Health. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

12 The 3MDG project is funded by a consortium of agencies – Australian Agency for

International Development (AusAID), Danish International Development Agency (Danida), European Union, Swiss Confederation, Sweden, Department for International Development (DFID), and United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

16 To maintain MNTE status;

To achieve elimination of measles and control of rubella and CRS by 2020;

To strengthen and maintain strong surveillance systems for AEFI and other priority VPDs;

To introduce new and underused vaccines and new technology into routine immunization, supported by evidence of disease burden.14

Myanmar has recently seen a number of initiatives to perform in-depth evaluations of and strengthen aspects of its EPI. In 2015, the country conducted an Effective Vaccine Management (EVM) assessment. Key recommendations from this assessment included increasing vaccine storage significantly, assuring temperature control during storage and transport, and strengthening data and programme management.15 In response to this, a cold chain expansion and replacement plan was developed16 and has been partially implemented with funding from 3MDG. In 2016, the country also underwent an evaluation, supported by UNICEF,17 with the development of a Supply Chain Data Use Manual.18 The Joint Appraisal coordinated by Gavi in 2016 noted the following bottlenecks and impediments to the EPI: immunization equities; data quality with specific concerns around denominators; service delivery; cold chain and vaccine management; management of vaccine and injection materials; community participation; and human resource capacity.19 Through Gavi, Myanmar has also received funding for health system strengthening from 2017 to 2019. Although this funding is not EPI-specific, many of the bottlenecks that it seeks to address were noted in the Joint Appraisal and are directly linked to EPI performance. In terms of EPI, the funding will target demand creation, cold chain and vaccine supply management, leadership, management and coordination, service delivery, and data and health information systems.20

Finally, as a lower middle income country, Myanmar is expected to reach full self-sufficiency in terms of vaccine purchase by 2025. A first step is self-self-sufficiency with regard to the traditional EPI vaccines by 2017. This goal is supported by the proposal for

14

Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2017 – 2021. Ministry of Health and Sport. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

15

Dissemination of Effective Vaccine Management Assessment (EVMA) Findings. 25 May 2015. UNICEF. Presentation made at Partner Meeting.

16 Myanmar cEVM Improvement Plan. 2016-2021. 2015. Ministry of Health and Sport.

Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

17 Immunization Supply Chain Data Use in Myanmar. Situational Report. 201. UNICEF 18

Myanmar Immunization Supply Chain Data Use Manual. Generation, collection, analysis and use of supply chain data. 2016. Ministry of Health and Sport. Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

19

Joint appraisal report. Myanmar. 2016. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

20

17

subscription to the VII,21 developed by the MoHS and submitted to the Ministry of Planning and Finance (MoPF) for approval.22 Given the depth and robustness of these assessments, the EPI review team has focused its energies on other aspects of the immunization programme while still touching on such critical facets as programme financing and iSC.

National EPI Schedule

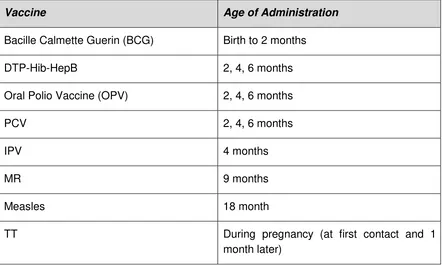

In 2016, the EPI schedule in Myanmar is as summarized below. Table 1. EPI schedule, Myanmar, 2016

Vaccine Age of Administration

Bacille Calmette Guerin (BCG) Birth to 2 months

DTP-Hib-HepB 2, 4, 6 months

Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) 2, 4, 6 months

PCV 2, 4, 6 months

IPV 4 months

MR 9 months

Measles 18 month

TT During pregnancy (at first contact and 1

month later)

As of 2015, IPV is offered with the second dose of pentavalent vaccine and the second dose of OPV, at the age of four months. PCV has been added to the vaccine schedule as of July 2016.

EPI Service Delivery

Vaccines in Myanmar are delivered through four different approaches: fixed, outreach, mobile and ‘crash’. Fixed immunization sites are located in maternal child health centres, urban health centres and township hospitals in urban settings, and in rural health centres

21 The VII is a UNICEF-based initiative established in 1991. It provides a financial mechanism to

ensure a systematic, sustainable vaccine supply for countries which can afford to finance their own vaccine needs but may require certain support services.

22Myanmar’s Plan for Subscription to the VII. 2016. Ministry of Health and Sport. Republic of

18

(RHCs) and sub-centres (RHSCs) in rural areas. Approximately 80% of immunization services are provided through outreach services. Outreach services are defined as

‘monthly, routine immunization services provided by a midwife away from her resident village in areas which are easily accessible’. Hard-to-reach and conflict zones are accessed through mobile or crash approaches. Mobile approaches are described as

‘routine immunization services provided by a midwife away from her resident villages in areas that are not easily accessible. Services may or may not be given monthly, but (are

given) a minimum of six times a year’ while crash approaches are ‘special immunization services provided by a group of health workers to cover hard-to-reach areas during the open season at least three times per year. These crash services are normally mobilized as a campaign, require extra resources and target all children under three years of age at least and women of child bearing age’.23

Financing of Immunization Programme

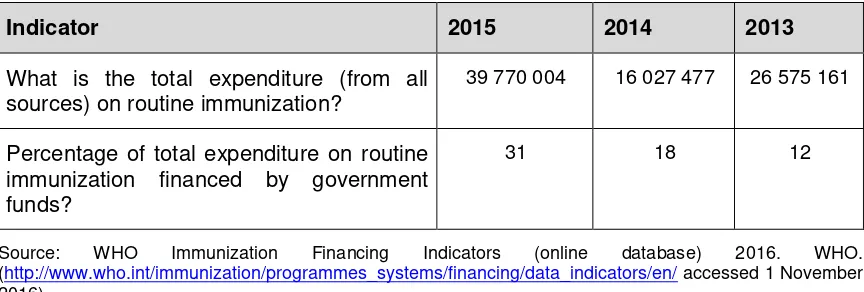

Financial indicators reported to WHO for years 2013, 2014 and 2015 are below.

Table 2. Financial indicators reported to WHO, Myanmar, 2013-2015 (all fund amounts in US$)

Indicator 2015 2014 2013

Are there line items in the national budget specifically for the purchase of vaccines used in routine immunizations?

Yes Yes Yes

Is there a line item in the national budget for the purchase of injection supplies (such as syringes, needles and safety boxes)

Percentage of total expenditure on vaccines financed by government funds

19

Indicator 2015 2014 2013

What is the total expenditure (from all sources) on routine immunization?

39 770 004 16 027 477 26 575 161

Percentage of total expenditure on routine immunization financed by government funds?

31 18 12

Source: WHO Immunization Financing Indicators (online database) 2016. WHO. (http://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/financing/data_indicators/en/ accessed 1 November 2016)

EPI Performance

WHO and UNICEF best estimates for vaccine coverage in Myanmar show that, over the past four years, coverage of antigens has either plateaued or decreased (Table 3). Variations in estimates of national vaccination coverage are evident in the differences among WHO and UNICEF best estimates for vaccine coverage, country estimates and Demographic Health Survey (DHS) 2015-2016 results (Tables 3 & 4). Differences in vaccination coverage between lowest and highest wealth quintiles and between poorest and best performing states/regions as estimated by survey are demonstrated in Table 4.

Table 3. Vaccination coverage: WHO and UNICEF best estimates and country estimates. Myanmar, 2012-2015.

2012 2013 2014 2015

BE* CE** BE CE BE CE BE CE

BCG 87 87 86 86 86 92 86 94

DTP1- 89 89 90 90 90 92 90 94

DTP3 84 84 75 75 75 88 75 89

HepB 3 58 -- 75 72 75 88 75 89

Hib3 75 72 75 88 75 89

IPV1 8 93

MCV1 84 84 86 86 86 88 86 84

MCV2 80 80 80 82 80 78

TT2plus 85 85 81 81 85 85 83 83

Pol3 87 87 76 76 76 88 76 89

RCV1 86 84

Source: WHO Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: Monitoring System. 2016 Global Summary (online data base). WHO

20

%5D=MMR accessed Sept 12, 2016). *BE: WHO and UNICEF best estimates of vaccine coverage; **CE.: Country estimates

Table 4. DHS estimates of vaccination coverage. Myanmar, 2015-2016

Nation

Source: Ministry of Health and Sports (MoHS) and ICF. Myanmar Demographic and Health Survey 2015-16. May Pyi Taw, Myanmar, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: Ministry of Health and Sports and ICF (https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR324/FR324.pdf, accessed 20 June 2017).

*Penta1: First dose of pentavalent vaccine (DTP-HepB-Hib) **Penta3: Third dose of pentavalent vaccine

†Most poorly performing state/region with regard to coverage for the specific vaccine

‡Best performing state/region with regard to coverage for the specific vaccine

VPD Surveillance

Myanmar has mandatory monthly aggregate reporting of 17 diseases, including eight VPDs or syndromes, some of whose causes are vaccine preventable. These eight VPDs or syndromes are: acute flaccid paralysis (AFP); measles; tetanus; whooping cough; diphtheria; acute respiratory infection/pneumonia; viral hepatitis and meningitis. AFP, measles and NT have case based reporting, are reported weekly, and are subject to both active and passive surveillance. Routine data analyses performed on the monthly reports by VPD or syndrome include:

number of cases and deaths per month,

number of cases and deaths per township, and number of cases by sex and age.

21 Status of VPDs

VPDs reported to WHO for 2013 - 2015 are summarized below.

Table 5. VPDs reported to WHO, 2013 – 2016

Source: WHO Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: Monitoring System. 2016 Global Summary (online data base). WHO

(http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/countries?countrycriteria%5Bcountry%5D%5B %5D=MMR accessed 21 June 2017). Excludes one type 1 VDPV in 2012

*Polio refers to all polio cases (indigenous or imported) including polio cases caused by cVDPV. The two cVDPV2 cases identified in 2015 are not included in the official report on this website.

R

EVIEWO

BJECTIVESThis review focused on the following core areas: government support to EPI,

VPD surveillance,

progress in meeting global and regional goals, and

Considerations around new and underutilized vaccine introduction (NUVI). The objectives of the EPI Review were:

to understand which children in Myanmar are not being fully immunized and the reasons that this is occurring. To the extent possible, efforts were made to assess areas with limited access to government services and increased reliance on other providers such as NGOs or local administrations;

to determine if the VPD surveillance system meets national and global targets and is currently able to detect any VPD outbreaks; this would include laboratory support and data management systems;

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Diphtheria 19 38 29 87 136

Japanese encephalitis 14 3 50 113 393

Measles 2 175 1 010 122 6 266

Pertussis 2 14 5 5 2

Polio* 0 0 0 2 0

Rubella 21 23 30 34 10

22

to determine if the strategies being implemented for measles and rubella objectives are adequate to maintain or achieve targets;

to assess how strategies and capacities of the immunization programme need to be strengthened to sustain polio-free status and MNTE, accelerate hepatitis B control and uniformly increase coverage for all routine vaccines; this would include vaccine and supply management, AEFI management, financing and sustainability.

As mentioned previously, in 2015 Myanmar experienced a cVDPV outbreak in the state of Rakhine. A cVDPV outbreak response assessment (OBRA) was scheduled for mid-2016. As programme areas to be reviewed for the OBRA were also relevant to the EPI review, a decision was taken in conjunction with the MoHS and partners to hold these two evaluations concurrently. Teams traveling to Rakhine as well as to Shan South considered the same issues that all teams did but paid particular attention to AFP surveillance and the quality of polio supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) that were conducted to respond to the cVDPV outbreak. The OBRA is detailed in a separate report.24

M

ETHODOLOGYThe MoHS and WHO’s Regional Office for South-East Asia and the WHO Office in Myanmar collaborated to assemble a review team of Myanmar nationals and internationals, including representatives from WHO, UNICEF, the United States Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC), Gavi, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Ministry of Health of Indonesia (Annex 1). The team addressed the core questions through a desk review of relevant policies and guidelines; secondary analysis of available data; interviews with key stakeholders, policy makers, and programme staff; visits to hospitals and direct observation of programme implementation at field sites in Myanmar.

In consultation with WHO’s Regional Office for South-East Asia, the MoHS of Myanmar selected the areas and the facilities for site visits. These sites included urban and rural locations, areas with high and low coverage, hard-to-reach areas, conflict areas, areas with migratory populations, and areas with recent outbreaks of VPDs. The states/regions of Chin, Kachin, Kayah, Magway, Naypitaw, Sagaing, and Shan East were not visited.

24

WHO. Regional Office for South-East Asia. Immunization . Documents and Publications. External Second Assessment: Circulating Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus Type 2 (cVPDV2) Outbreak Response, Myanmar, 25 September-8 October 2016. Available at

23

Figure 4. Map of Myanmar showing sites visited by the review team

Upon returning to Naypitaw, the field teams presented their findings and assessments to each other through extensive discussions on 5-6 October. The consensus conclusions and recommendations were shared on 7 October at a forum led by the Director General (DG) of the DoPH and attended by government public health programme directors and policy makers from the national, regional, and district levels as well as other key stakeholders. On 8 October the team leader and SEARO focal staff person met with the Minister of Health and Sport to discuss findings and recommendations.

L

IMITATIONS24

F

INDINGS ANDK

EYR

ECOMMENDATIONS BYT

OPICA

REAGeneral

In general, Myanmar has many areas of strength in its immunization and VPD surveillance systems. These include extremely dedicated staff, a very good national laboratory, and renewed commitment to reaching the unreached and improving immunization coverage. Nonetheless, the programme is challenged in a number of ways: financially, it remains heavily dependent on external funding; there are large inequities between townships, particularly those in conflict zones, self-administered regions and other hard-to-reach areas; persistent language, transportation and operational cost barriers for health workers exist; frontline staff are overburdened in the face of sanctioned but vacant posts; and challenges with monitoring and quality of reported data are present. Findings and key recommendations are outlined below.

Government Support

Context

Government support is critical to a well-functioning immunization system. Government support includes high level advocacy for the programme; dedicated and adequate funding; strong governance and policies; vaccine licensing, procurement and management; demand generation; and support for service delivery.

Findings

Advocacy and Financing

25 Health Financing and Costs of the CEPI

Health Expenditures

In 2014, Myanmar’s total health expenditure (THE) was 2% of GDP, of which private health expenditures made up 54%. THE per capita in 2014 was US$ 20, at the upper end of the rising trend in THE per capita which has occurred since 2007. Although THE as a percentage of GDP was stable from 2004 to 2014, the percentage represented by government expenditures has increased from a low of 9% in 2005 to a high of 46% in 2014. While the percentage of THE represented by private health expenditures has fallen over time, the percentage of these private health expenditures paid for out of pocket remains high at 94% in 2014, similar to what it has been for the preceding decade. THE as a percentage of GDP and THE per capita remain low when compared to other countries in the region at a similar income level25. While THE in terms of percentage of GDP has remained stable, purchasing power parity has almost doubled from 2008 to 2014.26 Health financing is clearly critical in the context of Sustainable Development Goals and Universal Health Care (UHC), and thus very relevant to the overall financing of the immunization programme.

Costs and Financing of CEPI

In 2015, the total cost of Myanmar’s immunization programme, including VPD surveillance, was US$ 67.0 million (Table 6). Of this, 19% was spent on vaccine and injection supplies for routine immunization and 41% was spent on SIAs. The remaining costs were allocated to programme management (2%), service delivery (5%), disease surveillance (3%), and advocacy and communication (5%). Fourteen percent was contributed to shared health system costs. This year was unusual in that it saw both a wide age range MR campaign and a polio vaccination outbreak response campaign for children aged less than 5 years, resulting in SIA costs of more than US$ 27 million. Because SIAs are associated with high but non-recurrent costs, it is important to consider the routine immunization programme independent of SIAs when conducting financial analyses of cost projections.

25

In Nepal THE for 2014 represented 6% of GDP and had a per capita value of US$ 40; In Bangladesh, THE for 2014 represented of 3% GDP and had a per capita value of US$ 31.

26

Global Health Expenditures. NHA Indicators. On line database. WHO.

26

Table 6. Baseline cost profile of immunization programme in 2015

Cost Category Expenditure 2015 (US$ ) in % of Total

Vaccine and Injection Supplies (Routine Immunisation

Only) 12 708 157 19 Service Delivery 3 455 111 5 Advocacy and Communication 3 041 338 5 Monitoring and Disease Surveillance 1 752 758 3 Program Management 1 012 618 2 Capital Costs 8 412 403 12 Supplemental Immunization Activities (includes vaccine

and operation costs) 27 568 686 41 Shared Health Systems Costs 9 387 619 14

Total 67 338 690 100

Source: Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2017 – 2021. MoHS. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar.

The government financed 7% of the overall immunization programme (including SIAs) and 14% of the routine immunization programme.27 This funding went for health worker salaries, and operational, transportation, and building costs. Gavi was the largest source of funding, financing 56% of the costs of the programme. The second largest source of financing was 3MDG (15%); funding from this consortium went towards purchasing new cold chain equipment through UNICEF. Other sources of financing were UNICEF for traditional vaccines and injection supplies (5%), Gavi funding passed through UNICEF (6%) and WHO (4%) for training, microplanning, and information, education and communication (IEC)/social mobilization, and US CDC funding channelled through WHO for surveillance and the polio SIA (7%).

27

This figure, drawn from the cMYP, is less than half that reported to WHO: WHO Immunization Financing Indicators (online database) 2016. WHO.

(http://www.who.int/immunization/programmes_systems/financing/data_indicators/en/

27 Financial Projections for CEPI, 2017-2021

The cMYP 2017-2021 includes projections for the costs of CEPI. The annual requirements are between US$ 59 million and US$ 73 million with fluctuations mainly explained by the planned SIAs (for example, JE vaccine and MR). The table below aggregates the costs over the five-year period of the plan.

Table 7. Future immunization programme resource requirements, 2017-2021

Cost Category US$ % of

Total

Vaccine Supply and Injection Supplies (Routine

Immunization Only) 149 067 618 47

Service Delivery 18 255 600 6

Advocacy and Communication 7 962 181 3

Monitoring and Disease Surveillance 9 250 949 3

Programme Management 22 319 389 7

SIAs (including vaccine and operational costs) 26 048 499 7

Shared Health Systems Costs 62 411 219 20

Total 315 959 384 100

Source: Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2017 – 2021. Section 4.2, p. 40 MoHS. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar

The main driver of future costs is the introduction of new vaccines (PCV in 2016, JE in 2017, rotavirus in 2018, HPV in 2019). The total costs for traditional and new vaccines are projected to increase from US$ 12.7 million in 2015 to US$ 27.1 million in 2021. With a 2014 gross national income (GNI) of US$1 270 per capita, Myanmar is in a phase of preparatory transition from being eligible to no longer being eligible for Gavi financing. The country is projected to enter the accelerated transition phase with regards to eligibility for Gavi funding in 2020 (depending on actual GNI growth rates). The government of Myanmar is aware that co-financing obligations for Gavi-supported vaccines will increase over time and is developing appropriate budget provisions and plans for 2016 and 2017.

28

of the EPI by committing to finance the traditional vaccines previously covered by UNICEF and to co-finance Gavi-supported vaccines, beginning with co-financing of the Gavi-funded pentavalent vaccine and PCV in 2016 (see Vaccine Procurement and Funding, below).

The cMYP 2017-2021 also develops several comprehensive and, at times innovative, strategies to improve the financial sustainability of the EPI. These are to:

increase funding from the government and external partners through conducting advocacy meetings at all levels;

increase spending on the immunization program by building community ownership through community participation and local resource mobilization in immunization service delivery;

improve efficiency of the immunization program through contracting a third party for vaccine transportation in urban settings, establishing a well-functioning EPI store for both vaccines and dry goods; and implementing the EVM improvement plan;

conduct cost-effectiveness studies of new vaccines and VPD surveillance; and

develop a financial sustainability plan, including creation of an “immunization trust fund”.28

Although none of these strategies has been fully explored as yet, they remain an excellent starting point to increase the resource base and the efficiency of the EPI. During field visits, lack of adequate township resources to fund basic operational costs, such as transportation and daily allowances, was noted. Disbursement of funds from central to township level was also noted to involve a complex and slow process.

Policy and Governance

National and Subnational Plans

Myanmar is currently developing a National Health Plan (NHP) 2017 – 2021, which covers communicable and non-communicable disease, including improving new-born and child health, strengthening the health system, and increasing coverage in border, peri-urban and rural areas. Plans for the EPI, including disease and programme-specific objectives, are incorporated into the NHP. In addition, immunization was included among the top priorities of the new government in its ‘100 Days Health Plan’, with a focus on introduction of new vaccines and increasing routine immunization coverage.29

28 Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2017 – 2021. Section 4.2, pp 51. MoHS. The Republic of the

Union of Myanmar

29

Ministries clarify undertakings in first 100 days. The Republic of the Union of Myanmar

President’s Office. (http://www.president-office.gov.mm/en/?q=issues/public-service/id-6550

29

The country’s most recent cMYP covers the period from 2017 to 2020.30 An annual work plan is also developed at state/regional level. In addition, each township develops an annual microplan for EPI.

National Oversight and Advisory Bodies

National oversight and advisory bodies include the National Committee on Immunization Practices (NCIP), the National Committee for the Certification of Polio Eradication (NCCPE), the National Polio Expert Review Committee (NPERC), National Polio Laboratory Containment Committee (NPLCC), the (measles and rubella) National Verification Committee (NVC), and the Adverse Event Following Immunization (AEFI) oversight committee.

All committees have membership drawn from a range of disciplines, including paediatricians, public health experts, and epidemiologists; many individuals are members of multiple committees. The NCCPE has functioned since 1999, and reports regularly to the Regional Commission for the Certification of Polio Eradication. The NCIP was established in 2009, with a charter written in 2013. This charter generally follows WHO recommendations, although it does not mandate rotation of members or a chairperson who is independent of government. Due process as outlined in the charter is routinely followed by the NCIP, which makes decisions on the introduction of new vaccines, changes in vaccine schedules, and other vaccine-related issues. All recommendations from the NCIP are referred to the MoHS for approval prior to implementation. Most decisions by the NCIP are unanimous; on the few occasions where a vote is necessary, this vote is conducted anonymously. The committee has formal terms of reference and meets at least twice annually. Members must reveal any conflicts of interest; on the rare occasions that these exist, members recuse themselves from discussion and voting. The decision to introduce a vaccine is made following a review of data, including information as available on the local burden of disease. The agenda for NCIP meetings is proposed by the secretariat, and approved by the MoHS. In general, it reflects matters that are topical for CEPI. The NVC is the most recently constituted advisory body, holding its first meeting in mid-2016. The NCIP, NCCPE, NVC and AEFI oversight committees are chaired by the DG, although his attendance at meetings is often limited by other obligations. The chair of the NPERC is a neurologist, while the chair of the NPLCC is the director of the NHL. The secretariat for all bodies is the EPI Manager. In general, support from the secretariat is excellent, but at times oversight and advisory body members do not have timely access to preparatory materials as these are shared electronically, and not all members have the facilities necessary to download and print documents.

30 Comprehensive Multi-Year Plan 2017 – 2021. Ministry of Health and Sport. The Republic

30 AEFI31

Passive surveillance for AEFI prioritizing serious or publicized events was initiated in 2001. In 2015, under the umbrella of the requirements for vaccine safety covered by the 1972 Public Health Law and 1992 National Drug Law, the MoHS issued AEFI surveillance guidelines aligned with WHO recommendations. Currently there is no dedicated budget for vaccine safety in the MoHS budget. The key national authorities implementing AEFI surveillance include the Food and Drug Administration Department, the DoPH and/or Department of Medical Services in charge of the Immunization Programme through the CEU, and the national AEFI oversight committee. Adverse events which occur following immunization with non-EPI vaccines are overseen by the Adverse Drug Reaction Committee, and are not handled by CEPI.

All AEFIs reported by health workers are required to initially be investigated by the township medical officer. Deaths, serious AEFIs, and AEFIs of significant public concern are investigated by the CEU and CEPI or AEFI committee once the report of the case is received. The AEFI committee then conducts causality assessment. Aggregated data from minor AEFIs is reported from townships using a hard copy reporting form and, for more serious AEFIs, a case investigation form. These forms are archived at national level, and key variables are entered into an electronic line-list database.

The MoHS provides feedback to the public regarding events of social concern. However, there is no mechanism for systematic feedback on AEFI surveillance performance or antigen-specific safety analyses.

Advance preparations for risk communication and interaction with the media have been made, including developing an information package and identifying spokespeople; monitoring the media with the recognition that it may be necessary to call a media conference in some circumstances; and, after the crisis has resolved, ensuring follow-up on any commitments that the government has made to the media.

In recent years, the AEFI surveillance system in Myanmar has successfully handled several events. In November 2012, following the introduction of Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib)-containing pentavalent vaccine, AEFI temporally linked to the administration of the pentavalent vaccine occurred. However, assessment showed no causal link, and the programme was able to continue using the pentavalent vaccine. In January 2015, serious AEFIs occurred during a nation-wide MR campaign, and were well-handled. In March 2016, there was a coincidental cluster of neonatal sepsis cases following immunization of babies with hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) in Bagot General Hospital; the programme was able to successfully respond to this cluster.

31

31

In 2015, the reported rate of AEFI exceeded 10 cases per 100 000 surviving infants in Myanmar, considered by WHO to be the benchmark for sensitivity of surveillance. In the 2015 MR campaign, a total of 3 473 AEFIs cases were reported of which 3 339 were minor AEFI and 134 serious AEFI.

Figure 5. Report routing, timeline and mandated actions for AEFI