Bank–Firm

Relationships: Do

Perceptions Vary

by Gender?

Patrick Saparito

Amanda Elam

Candida Brush

This study examines how small-business owners’/managers’ perceptions about their banking relationships are influenced by the gender of both the small-business owner/ manager and the bank manager. This study draws from social network theory and status expectations state theory to test how gender influences key perceptions about the bank–firm relationship. Using 696 matched firm owner/manager–bank manager pairs, our results show that male–male pairs of business owner/managers and bankers had the highest levels of trust, satisfaction with credit access, and bank knowledge, while female–female pairs had the lowest levels for each measure; with mixed pairs in the middle on all accounts.

Introduction

The number of female business owners is rising rapidly and many are creating substantial businesses. While most privately held businesses in the United States are majority-owned by men (62.5%), women continue to start businesses at three to four times the rate of men (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2007). In the United States, there are more than 10.1 million women-owned firms comprising 40% of all privately held firms, employing more than 13 million people, and generating $1.9 trillion in sales as of 2008 (Center for Women’s Business Research, 2009). Commercial banks are the primary source of funding to small firms, dwarfing other debt markets and venture capital financ-ing (Berger & Udell, 1998). Further, despite many programs to foster loans to small businesses, constricted credit access continues to plague small firms (Coleman & Robb, 2009). We propose that issues surrounding bank–firm relationships are particularly impor-tant for female small-business owners who rely more heavily on commercial and personal debt, or personal savings and investments, with only an extremely small percentage drawing on private equity (Brush, Carter, Gatewood, Greene, & Hart, 2004; Coleman, 2000; Coleman & Robb; Watson, Newby, & Mahuka, 2009).

Please send correspondence to: Patrick Saparito, tel.: 610-660-1157; e-mail: patrick.saparito@sju.edu, to Amanda Elam at amanda.elam@gmail.com, and to Candida Brush at crbrush@babson.edu.

P

T

E

&

1042-2587

© 2012 Baylor University

Research on gender differences in the access to and use of credit for new and small firms is mixed. When controlling for various factors including industry and growth, women-owned firms are no more likely to be turned down for credit or to receive credit with less favorable terms (Orser, Riding, & Manley, 2006). Controlling for key industry and business factors, Robb and Wolken (2005) found no differences in bank lending practices, approval rates, or credit terms between men-owned and women-owned busi-nesses. Other research shows that while women place more importance on relational factors and advice in their interaction with banks, no gender differences exist with respect to the terms and conditions of bank financing, or the provision of service (McKechnie, Ennew, & Read, 1998). However, several studies challenge these findings with evidence that women are charged higher interest rates and need greater collateral to meet financing terms (Coleman, 2000), suggesting that bank managers assess loan applications and interact with female business owners in a discriminatory fashion (Buttner & Rosen, 1992; Carter, Shaw, Lam, & Wilson, 2007; Fay & Williams, 1993). In summary, the evidence that there are gender differences in the provision of credit is equivocal. However, what we do learn from these studies is that women tend to cluster into certain industries, have less industry experience, and smaller and slower growing firms than men (Coleman; McKechnie et al.; Orser et al.; Robb & Wolken).

Researchers generally agree that, compared with men, women have different expec-tations and perceptions for their businesses and banking relationships. Recent studies indicate that not only do female small-business owners start ventures with fewer resources, but they also have expectations for slower growth (Cliff, 1998) and are less familiar with credit sources (Carter, Brush, Greene, Gatewood, & Hart, 2003). Lower expectations for growth and a lack of familiarity with credit sources can cause borrowers to incur psychic costs associated with the loan application process (Kon & Storey, 2003). As such, women may be systematically more likely to be discouraged borrowers who choose not to enter into the credit market because of perceptions that their applications have a high probability of being rejected (Kon & Storey). This phenomenon may explain, in part, evidence from the Center for Women’s Business Research (CWBR) that shows that women are more likely than men to choose financial products based on positive experiences or relationships with lenders (CWBR, 2009). Hence, even though studies are mixed on whether or not female business owners are equally or less likely than male business owners to obtain bank financing, female business owners are still generally less satisfied with both the business-related and interpersonal aspects of their banking rela-tionships than male owners (Fabowale, Orser, & Riding, 1995). As such, important questions arise as to whether female business owners view their relationships with banks differently than do male owners (Coleman & Carsky, 1996), and whether the bank officer’s gender influences these perceptions.

men in male-typed jobs (Foschi, 2000; Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). We argue that these social type-casting ideals influence key perceptions in banking relationships.

Key Perceptions About the Bank–Firm Relationships

The perceptions of both bank officer and small-business owner/manager within bank– firm relationships play a pivotal role in the outcomes of bank–firm relationships (Haines, Riding, & Thomas, 1991; Holland, 1994; Saparito, Chen, & Sapienza, 2004; Uzzi & Lancaster, 2003). Guided by such perceptions, business owners choose to share informa-tion or expand business with banks and, in turn, banks choose to extend credit and other business services to small-business owners (Carter et al., 2007; Cole, Goldberg, & White, 2004; Holland; Kon & Storey, 2003; Saparito et al., 2004; Uzzi & Lancaster).

Research on gender’s influence on bank lending decisions has focused primarily on the perceptions of lending officers. Studies dealing with these key perceptions have identified the existence and use of subjective decision-making criteria that adversely affect female business owners’ access to credit (Carter et al., 2007; Cole et al., 2004; Fay & Williams, 1993). Despite loan officer training models that emphasize more objective, quantifiable criteria, such as capital assets, collateral, capacity, and conditions, research indicates that the character of the applicant stands out as a key basis for decision making among bank lending officers (Carter et al.). Use of such qualitative criteria may be especially common in smaller banks (i.e., under $1 billion in assets) as loan officers in these banks are more likely to consider their “personal interactions with and assessments of loan applicants” when making loan decisions (Cole et al., 2004, p. 249). Additionally, a recent focus group study found distinct differences between the processes that male and female lending officers use in their decision making (Carter et al.). Male lending officers tend to rely more on gut instinct, rapport, and a diffuse sense of the overall process than female lending officers, who tend to focus on formal lending models that include specific lending terms, quality of the business plan, and the presence of brokers. Together, these findings have decided implications for demand-side arguments on the limited access to credit experienced by female business owners, especially with key structural controls concerning business characteristics and industry differences in place, but offer little insight into the supply-side arguments on the self-selection of female business owners out of the process of applying for credit (Carter et al.).

In this section, we introduce several factors of particular importance to small-business owner/managers and bank officers. We draw heavily from the research of Haines and colleagues (e.g., Haines et al., 1991; Riding, Haines, & Thomas, 1994) whose early work helped bring to light three of the four perceptual variables upon which we focus. The four key perceptions in our model are: trust between firm and bank (Saparito et al., 2004; Uzzi, 1999; Uzzi & Lancaster, 2003), the firm’s satisfaction with access to credit (Dunkelberg, Scott, & Cox, 1984; Ennew & Binks, 1993, 1997; Haines et al.; Riding et al.; Uzzi), a bank’s knowledge about the firm (Haines et al.; Uzzi), and small business proclivity to shop for alternate financial institutions (Haines et al.; Riding et al.; Saparito et al.).

Trust

Trust is defined as the intention of one party to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another party (Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, 1998). The role of trust in investor–small firm relationships has received increasing attention (e.g., Saparito et al., 2004; Uzzi, 1999; Uzzi & Lancaster, 2003; Yli-Renko, Autio, & Sapienza, 2001). For example, research finds that trust-filled rela-tionships (i.e., reciprocal trust) is positively associated with greater knowledge transfer between investors and emerging firms (Uzzi & Lancaster; Yli-Renko et al.). Trust facili-tates a more timely, relevant, and fine-grained flow of knowledge by providing expecta-tions that sensitive knowledge will not be misappropriated (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Rowley, Behrens, & Krackhardt, 2000). Moreover, trust provides connections between parties that facilitate strong self-enforcing norms, expectations of reciprocity, and long-term commitment to relationships (Uzzi). Indeed, Saparito and colleagues found that a small firm’s trust in the bank reduced the firm’s likelihood of switching to an alternative bank and Berger and Udell (2002) found that a bank manager’s trust in the small firm is positively associated with a small firm’s access to credit. Thus, economic transactions embedded in trust-filled relationships “reduce fears of misappropriation because transac-tors anticipate that others will not voluntarily engage in opportunistic behaviors” (Uzzi, p. 484). Past research has studied trust from the perspective of the bank (e.g., Berger & Udell, 2002; Uzzi), from the perspective of the small firm (e.g., Saparito et al.), and the reciprocal trust within investor–firm relationships (Uzzi & Lancaster; Yli-Renko et al.). This research focuses on how gender influences various perceptions, including trust, from the perspective of the small-firm owner/manager.

Satisfaction With Access to Credit

Satisfaction with access to credit refers to a small-firm owner’s/manager’s satisfaction with the amount of credit generally made available by the bank relative to the size of the loan request; the terms of attaining credit (e.g., collateral or equity investment require-ments, etc.); and the interest rate (Ennew & Binks, 1993, 1997; Haines et al., 1991; Riding et al., 1994). Adequate access to financial resources is essential to new and small firm growth, and barriers to credit access can: confine and avert entrepreneurial efforts (Churchill & Lewis, 1986; Kirzner, 1982); result in operating difficulties or bankruptcy (Coleman, 2000; Laitinen, 1991); and, ultimately, affect the overall economic health of the business (Berger & Udell, 1998). As such, satisfaction with access to credit is critically important to how small-business owners and managers make sense of the relationship with their bank (Dunkelberg et al., 1984; Riding et al.).

Bank Knowledge About the Firm

to restrict a small firm’s credit access (Diamond). Thus, bank knowledge about a firm is presumed to be positively associated with small-firm credit access (Petersen & Rajan; Uzzi & Lancaster).

While all scholars agree that knowledge plays a pivotal role in bank–firm relation-ships, empirical work in this area has measured knowledge in various ways. Petersen and Rajan (1994) did not directly measure knowledge, but used the length and breadth of the bank–firm relationship as a proxy for knowledge. Their assumption was that longer and broader bank–firm relationships would allow the bank to accumulate greater knowledge about the small firm. Alternatively, Uzzi and Lancaster’s (2003) qualitative study mea-sured knowledge through a series of interviews with bank loan officers. A third approach to measuring knowledge has been to ask small-firm owners/managers their perceptions about the bank’s knowledge of the firm’s business and marketplace (Binks, Ennew, & Reed, 1992; Ennew & Binks, 1993; Haines et al., 1991). Since this study explores how gender influences the small-firm owner’s/manager’s perceptions about the bank–firm relationship, we measure small-firm owners’/managers’ perceptions about the bank’s knowledge of the firm’s business and marketplace.

Likelihood of Switching to an Alternative Bank

A small firm’s likelihood of switching to an alternative bank refers to the small-firm owner’s/manager’s current and future perceptions regarding the potential to shop for and switch to an alternative financial institution (Riding et al., 1994). Customers’ shopping activity has received considerable scholarly interest because a durable bank–customer relationship positively impacts a bank’s profitability (Berlin & Mester, 1998). This prof-itability arises because banks avoid the cost of replacing customers who have shopped and switched to another bank. Additionally, customers who are committed to a particular bank may be willing to pay a small premium in interest rates and fees, and long-term banking relationships facilitate the achievement of economies of scope through selling additional financial services and products (Berlin & Mester). In short, many activities that banks undertake are designed to maintain and expand their economic relationships with existing customers.

Perceptions about inter-firm relationships are influenced by many factors, and gender is one of these important factors (Ely, 1995). To our knowledge, no research to date has considered the importance of both the lending officer’s and small-business owner’s gender simultaneously and how these together influence the business owner’s perception of the banking relationship. Additionally, while various studies have exam-ined different subsets of these four key perceptions of banking relationships, we believe this is the first study to examine all four of these perceptions in the same study. We explore these key perceptions in the next section and propose competing sets of hypoth-eses (homophily versus status expectations) for each key perception identified as central to the bank–firm relationship.

Gender and Perceptions of the Bank–Firm Relationship

et al., 1995; Treichel & Scott, 2006). In a 1990 membership survey of 2,763 Canadian Federation of Independent Business firms, Fabowale et al. found no difference in the credit terms between female and male business owners. Rather gender effects in credit terms including turndowns, approval ratios, and interest rates were explained by controls for business age and size, industry type, managerial experience, outside accounting expertise, and loan securities. However, when controlling for these key variables, these researchers did find that female business owners were much more likely to report higher levels of dissatisfaction with both the interpersonal and business aspects of the banking relationship. More recently, Treichel and Scott examined data from three independent National Federation of Independent Business surveys, collected in 1987, 1994, and 2001, and found no evidence of gender differences in turndown rates between male and female business owners when controlling for characteristics related to the business, the industry, and the bank. At the same time, they found that female business owners were significantly less likely to apply for loans in the first instance, and when approved, the loan rates were lower for female business owners. Controls for business and industry characteristics, as well as loan terms, had little influence on the gender differences in loan rates, leaving open the question of whether the lower reported rates of satisfaction in banking relationship are a reflection of discrimination or other factors coloring the experience for female business owners. In light of these findings, an exploration of the influence of gender on these central perceptual attributes of the bank–firm relationship is warranted.

Homophily

In this study, we draw on two theories to investigate the influence of gender on small-business owner–banker relationships. First, we consider social networking theory, particularly the concept of homophily. As one of the most robust findings in social network research, homophily has been defined as “the tendency for demographically similar people to associate with each other” (Brashears, 2008, p. 400). In other words, similarity breeds connection and results in social ties that not only confer important advantages, or resources, but also results in stronger ties that are more likely to endure over time (McPherson et al., 2001). Of course, while all social networks tend toward homogeneity, not all relationships are the same and some individuals are sought out more often than others (Kim & Aldrich, 2005). Indeed, research on gender and homophily suggests that male entrepreneurs accumulate better social capital than female entrepreneurs by developing larger professional networks with more diverse, powerful, and ultimately resourceful ties (Aldrich, Elam, & Reese, 1997; Brashears; Elam, 2008; Ibarra, 1992).

managers tend to have much less homophilous networks than other female and male managers, suggesting that high performing females may find ways to compensate for both the structural and status effects of homophily on social capital advantages.

Importantly, whether homophily confers advantages or disadvantages on a given individual depends on the activities in question. In a study of business discussion net-works, Renzulli et al. (2000) found that the gender homophily effect in business network strength is explained largely by the proportion of kin in the business owners’ network, placing business owners with a large proportion of demanding kin ties in their social networks at a critical disadvantage. Homophily effects represent key structural differences in the networks of female business owners that put them at a clear disad-vantage in terms of accessing professional resources, compared with male business owners. However, in the realm of caring work and kin-keeping activities, the structural effect of homophily likely confers important advantages when it comes to caring for family members, especially children. In this study, our focus is on the structural impact of homophilous ties between business owners and bankers and how these pairings affect perceptions of the banking relationship.

Status Expectations State Theory

Next we consider status expectations state theory, in particular the concept of cul-turally defined expectations of competence. Status expectations states refers to the cultural beliefs organized along the lines of social status differences, like gender, that set individual expectations about how the self or others will perform at a given task (Foschi, 2000; Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). An important distinction in this theory is the concept of salience—when gender is salient in the context of a particular task situation, cultural beliefs about gender function as rules of the game (Ridgeway & Correll). In effect, when gender is salient, double standards are applied in prejudgments of com-petence (Foschi).

Research on the double standards of competence applied in professional contexts indicates that women face considerable disadvantages in both prejudgments of compe-tence and assessments of performance (Foschi, 2000; Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). In laboratory studies modeling the hiring process, researchers have consistently found that men tend to be rated or selected for hire more often than women, notwithstanding evidence of higher qualifications for women (Foschi; Ridgeway & Correll). Moreover, studies have found that women tend to favor evidence of qualification and ability over gender status in appraisals of professional competence, as compared with men (Foschi; Foschi, Lai, & Sigerson, 1994).

Competing Hypotheses From Homophily and Status Expectations

The distinction between homophily and status effects has attracted little attention in entrepreneurship studies (Elam, 2008). One exception is Ruef, Aldrich, and Carter (2003) who found that homophily and ecological constraints work together to produce minority isolation among entrepreneurial founding teams. Typically, however, the application of the concept of homophily in social networking theory takes for granted the status differ-ences between men and women in the context of new/small-business ownership. In contrast, status expectations state theory makes explicit the possibility that status differ-ences resulting from gender-linked expectations of competence will vary with the task set as well as with the gender of the individual studied.

For this study, we develop four sets of hypotheses, comparing predictions of homoph-ily versus status expectations state effects on key aspects of small-business owner–banker relationships. We argue that both homophily and gender-linked status expectations of competence provide a basis for key perceptions in banking relationships. However, as theoretical constructs, each concept constitutes a distinct social process and must be considered separately.

Social networking theory posits that trust and positive perceptions are governed by the homophily mechanism (McPherson et al., 2001). In other words, individuals will experi-ence the highest levels of trust in relationships, or pairings, with similar others. As such, the homophily argument predicts that same gender pairings (male–male and female– female pairs) will show the highest levels of positive perceptions, followed by mixed-pair relationships with lower levels of trust and less positive perceptions.

In contrast, status expectations state theory argues that positive perceptions will most likely occur in relationships, or pairings, where the fit between the diffuse status charac-teristics of the person being judged (e.g., male or female) and the task set, or role, at hand (banker or small-business owner) follows widely held cultural ideals about gender and appropriate task sets (Foschi, 2000; Ridgeway & Correll, 2004). Both banking and business ownership are typically stereotyped as highly masculine endeavors (Ahl, 2004; Bird & Brush, 2003). Under the assumption that status expectations serve as the under-lying mechanism by which gender exerts an influence on the bank–firm relationship, the rankings should look quite different from those predicted by the homophily argument. In fact, the status expectations state theory argument predicts that for bank–manager/ business–owner relationships, respectively, we expect male–male pairings to have the most positive perceptions, followed by mixed pairings (i.e., female–male/male–female) and, finally by female–female pairings.

As a consequence, the competing hypotheses for these two theoretical perspectives appear as follows:

Homophily Status Expectations State Theory

Hypothesis 1a:Trust in the bank will be higher for male–male and female–female pairs compared with mixed pairs.

Hypothesis 1b:Trust in the bank will be highest for male–male pairs, followed by mixed pairs, and female–female pairs. Hypothesis 2a:Satisfaction with credit access will be higher for

male–male and female–female pairs compared with mixed pairs.

Hypothesis 2b:Satisfaction with credit access will be highest for male–male pairs, followed by mixed pairs, and female–female pairs.

Hypothesis 3a:Perceptions of the bank’s knowledge about the firm will be higher for male–male and female–female pairs compared with mixed pairs.

Hypothesis 3b:Perceptions of the bank’s knowledge about the firm will be highest for male–male pairs, followed by mixed pairs, and female–female pairs.

Hypothesis 4a:Likelihood of switching banks will be lower for male–male and female–female pairs compared with mixed pairs.

Research Methodology

We employed a matched-pair sample design of small-firm owners/managers and the bank managers who had responsibility for each of their firm’s accounts. The completion of the three-stage data collection resulted in 696 matched pairs of firm owners/managers– bank account managers. All dependent variables were collected directly from small-business owners/managers. This study design is appropriate given that the purpose of this study was to examine how gender influences firm owner’s/manager’s perceptions of the bank–firm relationship. Data regarding an individual’s gender and age were self-reported by both the small-firm owners/managers and the bank managers. Control variables were collected from the: small-firm owners/managers (i.e., firm size, firm age, growth rate, and business sector; the bank–firm relationship’s age; and whether the bank was the firm’s primary financial institution); bank (i.e., bank size) and the United States Federal Reserve (i.e., bank market competitiveness).

Participating Banks

In the first phase of data collection, we approached 286 banks in Connecticut, Missouri, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. This geographic frame includes a good mix of rural, suburban, and urban areas providing for potentially more generalizable results. Since large banks are generally less involved with small business clients (Cole et al., 2004; Petersen & Rajan, 1994), we limited variation associated with bank size by targeting moderately sized banks with total assets of $100 million to $10 billion. Twenty-two banks agreed to have surveys distributed to both their managers and their small and mid-sized commercial customers and bank managers. This represented a 7.67% participation rate. As we explain more fully below, we asked banks to provide a client list, a lending officer list, and permission to survey both groups. Therefore, we recognized that the survey methodology to attain a matched response of small-firm owners/managers–bank manag-ers was extensive and we were not surprised at this response rate. Participation rates between states did not differ significantly (c2=

4.55, not significant [n.s.]). The median total assets for banks that participated was $248.5 million versus $237.2 million for banks that did not, a difference that is not statistically significant (F=0.95, n.s.).

Sample of Small-Business Owners/Managers

Sample of Bank Managers

In the final phase of data collection, each responding small-business owner/manager identified the bank officer primarily responsible for the company’s account, and each participating bank notified bank employees to expect a survey from the research program. Two hundred sixty-three bank managers were identified and sent surveys. Cover letters indicated that all responses would be anonymous and confidential and surveys were directly returned to the research office in an enclosed and stamped envelope. Managers returned 217 surveys, representing an 82.51% response rate.

Statistical Procedures

We used multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) to test for differences in levels of trust, satisfaction with credit, perceptions of a bank’s knowledge about the firm, and likelihood to switch to an alternative bank between female–female, mixed gender, and male–male small-business owner/manager–bank manager pairs. In order to better isolate and identify differences in our dependent variables due to gender, we were careful to control for factors that are known to influence bank–small firm relationships and the perceptions of these relationships.

Measures Trust

We measured trust using Saparito et al.’s (2004) 4-item index measure. Using a

7-point scale (where 1=very rarely true and 7=very often true), small-firm customers rated the following items: (1) We feel that the bank would act in a fashion consistent with what we would recommend without prior discussion with us; (2) We can freely share concerns and problems about our company and know that they will respond construc-tively; (3) We can freely share concerns and problems about our company and know that they will be interested in listening; and (4) We share common business values with the bank (alpha=.89).

Satisfaction with Credit Access

We measuredsatisfaction with credit accessby a 5-item scale. Items were created and adapted from measures used in large national investigations of small business banking in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada (e.g., Dunkelberg et al., 1984; Ennew & Binks, 1997; Haines et al., 1991). The measure was pilot tested on a sample of small businesses that were clients of a small business development center in a Northeastern U.S. state. Using a 7-point scale (where 1=very dissatisfied and 7=very satisfied), small-firm customers rated the following items: (1) The credit amount that the bank generally makes available when our company makes loan requests; (2) The bank’s security and collateral requirements for obtaining a loan; (3) The bank’s requirements for personal/ company equity invested in the business prior to granting a loan; (4) The bank’s financial reporting requirements for granting a loan; and (5) Interest rates charged on loans (alpha=.91).

appropriate given that the purpose of the study was to examine how gender differences influence various perceptions of the bank–firm relationship.

Bank’s Knowledge of the Firm

Drawing upon the literature and previous measures (Binks et al., 1992; Haines et al., 1991), we created and adapted four items to measure abank’s knowledge of the firm. This measure was pilot tested along with the measure for customer satisfaction with credit. Using a 7-point scale (where 1=very dissatisfied and 7=very satisfied), small-firm customers rated: (1) The bank’s knowledge of our business; (2) The bank’s knowledge of the local market/community; (3) The bank’s anticipation of our credit and other financial needs; and (4) The bank’s anticipation of our financial needs other than credit (alpha=.92).

Likelihood of Switching to an Alternative Bank

We measured likelihood of switching to an alternative bank using Saparito et al.’s

(2004) 5-item measure. Using a 7-item scale (where 1=very unlikely and 7=very

likely), small-firm customers rated the extent to which they were likely within the next year to: (1) switch to an alternative bank to service their borrowing needs; (2) switch to an alternative bank for checking and other deposit accounts; (3) move accounts to banks with slightly more attractive interest rates; (4) move accounts to banks with slightly more attractive fees; and (5) shop for banks with more attractive fees and interest rates (alpha=.92).

Control Variables

We controlled for several factors considered to influence the nature of bank–firm relationships (Petersen & Rajan, 1994; Uzzi & Lancaster, 2003).

Bank Market Competitiveness

Less competitive banking markets are associated with greater credit constraint prob-lems (Berlin & Mester, 1998; Uzzi, 1999). Bank concentration has been shown to affect the access to and interest rates of loans (Petersen & Rajan, 1994; Uzzi). Additionally, less competitive banking markets also limits the ability of firms to switch to alternative banking institutions (Saparito et al., 2004). The U.S. Federal Reserve Bank measures the concentration of bank deposits across geographic banking markets via a bank concentra-tion index. Higher index numbers mean higher concentraconcentra-tions of deposits among banking institutions with fewer branches and alternatives. This is interpreted to mean less compe-tition within a given banking market (Petersen & Rajan). We used this more precise measure of bank competition within local markets instead of using more course-grained binary variables for the state in which a bank is located.

Bank Size

the size of the bank may reflect the relative importance of the customer to the bank and, hence, the bargaining power of the customer to make demands on the bank. Thus, we controlled for bank size by using the natural log of the bank’s total assets (Berlin & Mester; Petersen & Rajan).

Firm Size

The size of a borrowing firm may affect numerous facets of the bank–firm relationship including: bargaining power; importance to the bank; and access to credit (Petersen & Rajan, 1994; Riding et al., 1994; Wathne, Biong, & Heide, 2001). We used number of employeesandsales revenuesas size measures; the former may have an impact on indirect business for the bank, and the latter is more directly connected with the potential business of the specific customer firm with the bank.

Firm Growth Rate

Firms were resistant to reporting specific profitability figures. However, we were able to collect a measure of a firm’s growth rate. The growth rate of sales may signal the health of a firm as well as the potential future business for the bank (Berger & Udell, 1998; Berlin & Mester, 1998). Using a 7-point scale (where 1=decreasing rapidly and 7=increasing rapidly), small-firm customers rated the growth rate of their firm’s sales over the past 5 years (less if the firm was younger).

Firm Age

Firm age is positively associated with the likelihood of firm survival and it may be relatively more difficult for young firms to obtain alternative lines of credit at the same or better costs (Petersen & Rajan, 1994). Firm age was measured as the number of years the firm had been in operation.

Business Sector

A firm’s business sector can influence its borrowing needs, ability to provide col-lateral, and numerous other factors associated with its ability to attain loans (Berger & Udell, 1998; Berlin & Mester, 1998; Petersen & Rajan, 1994; Saparito et al., 2004). Consistent with the seminal work of Petersen and Rajan, we used the broad business sectors for controlling for these potential affects. We collected this data by providing small-firm business owners a list of broad business sector category names (e.g., Retail, Wholesale, Manufacturing, etc.) and asked the small-firm owner/manager to indicate which business sector best described the firm. Business sector was coded using dummy variables.

Firm–Bank Relationship Age

(Berlin & Mester; Petersen & Rajan; Uzzi). We measured the bank–firm relationship age as the number of years the firm had a business account with the bank.

Primary Bank

Whether or not a bank is the firm’s primary banking institution is also an important factor influencing: the amount of information exchanged between the bank and the firm, the firm’s credit access, and the likelihood of the firm switching to an alternative banking institution (Berlin & Mester, 1998; Petersen & Rajan, 1994; Saparito et al., 2004; Uzzi, 1999). Therefore, we measured whether the bank was the firm’s primary financial insti-tution using a dummy variable (1=if the bank was the firm’s primary bank and 0= oth-erwise).

Small-Firm Owner/Manager Age and Bank Manager Age

The business owner’s/manager’s age is often used as a proxy for human capital (experience) and positively related to performance (Bates, 1990). We collected the age of the small-firm owner/manager and bank manger directly from each respondent in the respective surveys by asking them to identify what category best described their age group (i.e., 21–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, more than 70). We coded this using a 7-point scale (1=21–30 to 7=more than 70).

Results

Responding bank managers and small-firm owner/managers were 47.1% and 27.6% female, respectively, with a median age range of 31–40 and 41–50, respectively. This age breakdown is consistent with the breakdown of small-business owners in the United States, whereby the bulk are between the ages of 45–54 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2007). Additionally, responding small-firm owners/managers within various business sectors ranged from 16.1% female in wholesale to 32% female in retail.

The correlations, means, and standard deviations appear in Table 1. As expected, trust, bank knowledge about a firm, and satisfaction with credit access all show large and highly significant positive correlations with one another (each atp<.01). Also as expected, trust, bank knowledge about a firm, and satisfaction with credit access show large and highly significant negative correlations with the likelihood of switching to an alternative bank (each at p<.01).

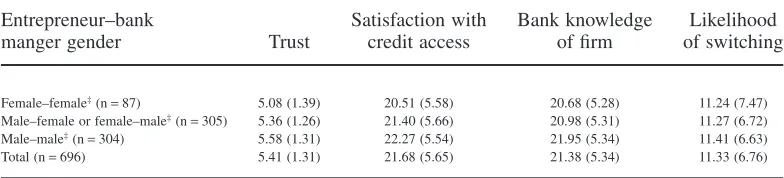

Because each of these variables is highly correlated with one another, it is appropriate to simultaneously test for differences using MANCOVA instead of separate ANCOVA analyses for each of the four dependent variables (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1995). Our hypotheses suggest two different orderings for the gender pairings—the homophily argument predicts that homophilous pairs (male–male and female–female) will produce the most favorable scores on test factors, while status expectations state theory suggests that male–male pairs will show best scores, followed by mixed gender pairs and female–female pairs. Statistical results support the assertion that gender pairings do influence the dependent variables (Wilks lambda l =.97, F8, 1286=2.66, p<.01).

Table 1

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Variables in the Study

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

1. BCI

2. Bank size -.02

3. Firm employees .00 .11**

4. Firm sales -.05 .14** .50**

5. Firm growth -.02 .06 .12** .20**

6. Firm age .03 -.03 .23** .20** -.12**

7. Relationship age -.07* -.12** .03 -.03 -.16** .35**

8. Primary bank -.05 .08* -.06 -.06 -.03 .01 .15**

9. Firm owner age -.05 -.02 .03 .06 -.09** .22** .20** -.02

10. Bank manager age .18** -.11** .00 -.06 -.07 -.01 .14** .02 .10**

11. Trust .03 -.02 .05 .09** .06 .03 -.02 .14** .09** .03

12. Bank knowledge 0.04 -.04 .08* .10** .04 .00 -.01 .10** .03 .02 .73**

13. Customer satisfaction 0.02 .00 .03 .08* .04 -.03 .00 .10** .04 .04 .65** .69**

14. Likelihood of switching 0.04 .03 .02 -.03 -.02 .02 .01 -24** -.08* -.01 -.53** -.53** -.52**

Mean 1,567.44 855.41 19.48 3.32 5.09 21.13 9.65 .86 3.37 2.93 21.57 21.02 21.61 14.29

Standard deviation 656.61 1,636.08 41.11 1.85 1.18 21.57 11.03 .34 1.07 .95 5.19 5.45 5.51 8.33

BCI, bank concentration index.

850

ENTREPRENEURSHIP

THEOR

Y

and

PRA

(F=5.67, p<.001). This pattern of results suggests that the status expectations state theory argument for differences in trust (hypothesis 1b) is supported, while the homophily argument for differences in trust (hypothesis 1a) is not supported.

Hypothesis 2a proposed a homophily argument for differences in satisfaction with credit access, while hypothesis 2b proposed that differences in levels of satisfaction with credit access would vary according to status expectations state theory. As shown in Table 2, female–female pairs show the lowest levels of satisfaction with credit access, mixed pairs an intermediate level of satisfaction with credit access, and male–male small-firm owners the most satisfaction with credit access (F=4.65,p<.01). Again, this pattern of results suggests that the status expectations state theory argument for differ-ences in satisfaction with credit access (hypothesis 2b) is supported, while the homophily argument for differences in satisfaction with credit access (hypothesis 2a) is not supported.

Hypothesis 3a proposed a homophily argument for differences in levels of small-firm owners’ perceptions concerning a bank’s knowledge of the firm, while hypothesis 3b proposed that differences in levels of a small-firm owners’ perceptions about a bank’s knowledge about the firm would vary according status expectations state theory. Again, the results in Table 2 show that female–female pairs have the lowest levels of small-firm owners’ perceptions about a bank’s knowledge, mixed pairs an intermediate level of small-firm owners’ perceptions about a bank’s knowledge, and male–male small-firm owners the highest small-firm owners’ perceptions about a bank’s knowledge (F=3.49, p<.05). Again, this pattern of results suggests that the status expectations state theory argument for a bank’s knowledge about the firm (hypothesis 3b) is supported, while the homophily argument concerning the bank’s knowledge of the firm (hypothesis 3a) is not supported.

Finally, hypothesis 4a proposed a homophily argument for differences in a small-firm owners’ likelihood of switching to an alternative bank, while hypothesis 4b proposed that differences in a small-firm owner’s likelihood of switching to an alternative bank would vary according to the status expectations state theory. As shown in Table 2, the differences between means for the likelihood of switching banks are not significant (F=0.10, n.s.). Thus, neither the homophily argument (hypothesis 4a) nor the status expectations state theory argument (hypothesis 4b) are supported.

Table 2

Differences in Means by Entrepreneur–Bank Manager Gender†

Entrepreneur–bank

manger gender Trust

Satisfaction with credit access

Bank knowledge of firm

Likelihood of switching

Female–female‡(n=87) 5.08 (1.39) 20.51 (5.58) 20.68 (5.28) 11.24 (7.47)

Male–female or female–male‡(n=305) 5.36 (1.26) 21.40 (5.66) 20.98 (5.31) 11.27 (6.72)

Male–male‡(n=304) 5.58 (1.31) 22.27 (5.54) 21.95 (5.34) 11.41 (6.63)

Total (n=696) 5.41 (1.31) 21.68 (5.65) 21.38 (5.34) 11.33 (6.76)

Discussion

We proposed a competing set of hypotheses drawing from homophily (hypotheses 1a, 2a, 3a, and 4a) and status expectations state theories (hypotheses 1b, 2b, 3b, and 4b). The homophily perspective proposes that the more we have in common, the more positive perceptions and expectations we have about the other party (Brashears, 2008). Connec-tions, so the argument goes, are more readily formed with similar others, perhaps leading to (or because of ) better communications. In contrast, the status expectations state perspective argues that, in the absence of better information, perceptions are based on mental models that support prejudgments of competence relative to a specific task (Foschi, 2000; Ridgeway & Correll, 2004).

Our findings suggest that perceptions about gender status and gender-appropriate work roles influence small-firm owner/manager perceptions about the bank–firm relation-ship and, as such, our findings were generally supportive of status expectations state theory. More specifically, our proposed hypotheses regarding a small-firm owner’s/ manager’s trust in the bank (hypothesis 1b), satisfaction with credit access (hypothesis 2b), and perception of the bank’s knowledge of the firm (hypothesis 3b) were supported. However, the status expectations state theory argument for differences in the likelihood of switching to an alternative bank (hypothesis 4b) was not supported. Our findings did not support any of the hypotheses based on the homophily argument.

While not all of our status expectations state theory hypotheses were supported, we did not expect a perfect fit. These findings advance our understanding about the way homophily and status expectations may shape the nature of bank–firm relationships. The homophily perspective argues that dealing with similar others produces predictable out-comes. Status expectations state theory argues that similarity is not sufficient because perceptions of competence of a predefined task will predict assessments of trustworthiness and fair treatment. In other words, when one party in a dyad does not conform to traditional occupational and gender expectations, the nature of the negotiations and interactions can be influenced as one or the other seeks to conform to gender stereotypes for the job at hand (Nelson, Maxfield, & Kolb, 2009). When parties are working to conform to certain status expectations, they may perceive the other person to be less trustworthy and/or to be less satisfied with the nature of the relationship. Our findings support earlier work by Ibarra (1992), who found homophily and status connections were positively correlated for men in advertising but negatively correlated for women. She argued that social networks play a role in influencing these results. It follows that if female business owners have few women in their financial networks, they would have certain expectations and perceived stereotypes about the likely competence of female bank managers. The extent to which gender stereotypes influence key perceptions of trust and satisfaction of the parties in banking relationships is a logical extension of this research.

trust in the bank (Uzzi, 1999). Further, a small firm’s trust in the bank could, in turn, reduce the business owner’s/manager’s likelihood of switching to an alternative bank (Saparito et al., 2004). Thus, trust may be a mediating mechanism between small-firm owner/manager perceptions of inadequate access to credit and the likelihood of switching to an alternative bank. Indeed, the correlation matrix in Table 1 shows strong (positive/ negative) correlations between each of the dependent variables. However, the dynamic interaction effects of perception of a bank’s knowledge about the small firm, trust in the bank, satisfaction with credit, and the likelihood of switching to an alternative bank are beyond the scope of this particular study.

Future Research

Our study has several limitations. First, the study’s design was quite extensive in that we asked banks to: provide us a list of clients; allow us to survey these clients; and then allow us to survey the associated bank managers. Clearly then, participating banks would likely have a bias toward an interest in lending to small firms. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, our study relies upon cross-sectional data and this limits our ability to examine how bank–firm relationships unfold. Longitudinal data could tease out these dynamic interactions. For example, research shows that longer-term banking relationships are correlated with greater access to credit (Petersen & Rajan, 1994). Therefore, if women are motivated to switch banks due to a lack of trust, this factor may decrease their potential to receive credit (Petersen & Rajan). As such, compared with a male small-firm owner, a female small-firm owner might less readily develop trusting beliefs in the future of the small firm–bank relationship. Consequently, the linkage between credit satisfaction, trust, and switching to an alternative bank might be weaker for women than for men.

Another limitation of cross-sectional data concerns the potential for change. Mental models become refined with experience. Hence, the tenure of the bank–firm relationship could impact the extent to which gender is salient for expectations of competence. We controlled for the duration of the relationship in this study. However, as female business owners and bankers become more common, cultural stereotypes will likely change, decreasing the influence of gender on bank–firm relationships. That said, female business owners are likely to become more accepted first in certain industries. For example, women are more likely to run businesses in retail, beauty/fashion, and financial service sectors, but are less likely to be in manufacturing, construction, and high-growth industries like technology and biotech. Longitudinal research on the impact of the changing gender composition of women’s business ownership in certain industries on broadly held cultural stereotypes could inform our expectations of the salience of gender in future bank–firm relationships.

comparable female business owners. These perceptions on the part of a bank manager might require small-business owners to transfer more (or less) information to the bank and might increase (or decrease) waiting times for a final loan decision. This situation, in turn, could affect a small firm’s perceptions about a bank’s knowledge of the small firm, trust in the bank, satisfaction with credit, and the likelihood of switching to an alternative bank. Future research based on mutual perceptions would allow researchers to examine these connections.

Conclusions

This study examined how the gender of the business owner and of the bank manager influences perceptions about the banking relationship. We drew from social network and status expectations state theories of gendered interaction, and tested hypotheses exploring the influence of gender on perceptions of trust, the bank’s knowledge of the firm, satis-faction with credit, and the likelihood of switching banks, as key factors in bank–firm relationships. Our findings offer strong support for a status expectations state theory perspective. Male–male pairings did indeed show the highest levels of trust, satisfaction with access to credit, feelings that the bank has high levels of knowledge about their firm, and the least likelihood of switching to an alternative bank. In contrast, we found that the female–female pairs demonstrated the lowest levels of trust, satisfaction with access to credit, feelings that the bank had the low levels of knowledge about their firm, and the most likelihood of switching to an alternative bank. Mixed gender fell in the middle.

This study makes two important contributions to the study of bank–firm relationships. Few studies have considered the likely influence of gender on the bank–firm relationship, and, even then, only examine how the gender of the bank manager, as a key decision maker, influences loan decisions for male and female business owners. Our findings indicate that the perceptions of the business owner hold important implications for the success of bank–firm relationships. Importantly, our study indicates that homophily is a limited measure for the investigation of gender and social network ties. Indeed, gender as a marker of social status should be considered as a distinct factor influencing bank–firm relationships and, consequently, resource acquisition and small business outcomes.

REFERENCES

Ahl, H. (2004).The scientific reproduction of gender inequality: A discourse analysis of research texts on women’s entrepreneurship. Stockholm, Sweden: Liber Copenhagen Business School Press.

Aldrich, H., Elam, A., & Reese, P. (1997). Strong ties, weak ties, and strangers: Do women business owners differ from men in their use of networking to obtain assistance? In S. Birley & I. MacMillan (Eds.),

Entrepreneurship in a global context(pp. 1–25). London, U.K.: Routledge.

Bates, T. (1990). Entrepreneur human capital inputs and small business longevity.The Review of Economics and Statistics,72, 551–559.

Berger, A. & Udell, B. (1998). The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle.Journal of Banking & Finance,22, 613–673.

Berlin, M. & Mester, L.J. (1998). On the profitability and cost of relationship lending.Journal of Banking & Finance,22, 873–898.

Binks, M. & Ennew, C. (1997). Smaller businesses and relationship banking: The impact of participative behavior.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,21(4), 83–92.

Binks, M.R., Ennew, C.T., & Reed, G.V. (1992). Information asymmetries and the provision of finance to small firms.International Small Business Journal,11, 35–46.

Bird, B.J. & Brush, C.G. (2003). A gendered perspective on organizational creation.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,26, 41–65.

Brashears, M.E. (2008). Gender and homophily: Differences in male and female association in Blau space.

Social Science Research,37, 400–415.

Brush, C.G., Carter, N.M., Gatewood, E.J., Greene, P.G., & Hart, M.M. (2004).Clearing the hurdles: Woman building growth businesses. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Burt, R.S. (1998). The gender of social capital.Rationality and Society,10, 5–46.

Buttner, E.H. & Rosen, B. (1992). Rejection in the loan application process: Male and female entrepreneurs’ perceptions and subsequent intentions.Journal of Small Business Management,30, 58–65.

Carter, N.M., Brush, C.G., Greene, P.G., Gatewood, E.J., & Hart, M.M. (2003). Women entrepreneurs who breakthrough to equity financing: The influence of human, social and financial capital. Venture Capital Journal,5, 1–28.

Carter, S., Shaw, E., Lam, W., & Wilson, F. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurship, and bank lending: The criteria and processes used by bank loan officers in assessing applications.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,31, 427–444.

Center for Women’s Business Research. (2009). Key facts about women-owned businesses. Available at: http://www.womensbusinessresearchcenter.org/research/keyfacts/, accessed 17 July 2011.

Chafetz, J. (1997). Feminist theory and sociology: Underutilized contributions for mainstream theory.Annual Review of Sociology,23, 97–107.

Churchill, G.A. (1991).Marketing research: Methodological foundations. Chicago, IL: Dryden.

Churchill, N. & Lewis, V. (1986). Bank lending to new and growing enterprises. Journal of Business Venturing,1, 193–206.

Cliff, J. (1998). Does one size fit all? Exploring the relationship between attitudes towards growth, gender, and business size.Journal of Business Venturing,13, 523–542.

Cole, R., Goldberg, L., & White, L. (2004). Cookie cutter vs. character: The micro structure of small business lending by large and small banks.Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis,39, 227–251.

Coleman, S. (2000). Access to capital and terms of credit: A comparison of men- and women-owned small businesses.Journal of Small Business Management,38, 37–52.

Coleman, S. & Carsky, M. (1996). Understanding the market of women-owned small businesses.Journal of Retail Banking Services,18, 47–50.

Coleman, S. & Robb, A. (2009). A comparison of new firm financing by gender: Evidence from the Kauffman Firm Survey Data.Small Business Economics,33, 397–411.

Diamond, D.W. (1991). Monitoring and reputation: The choice between bank loans and directly placed debt.

Dunkelberg, W., Scott, J., & Cox, E. (1984). Small business and the value of bank-customer relationships.

Journal of Bank Research,14, 248–258.

Elam, A. (2008). Gender and entrepreneurship: A multilevel theory and analysis. London, U.K.: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ely, R. (1995). The power in demography: Women’s social constructions of gender identity at work.Academy of Management Journal,38, 589–634.

Ennew, C. & Binks, M. (1993). Financing entrepreneurship in recession: Does the banking relationship constrain performance? In N. Churchill (Ed.),Frontiers of entrepreneurship research(pp. 481–495). Babson Park, MA: Center for Entrepreneurial Studies Babson College.

Ennew, C. & Binks, M. (1997). Information asymmetries, the banking relationship and the implications for growth. In P. Reynolds, P.P. McDougall, C.M. Mason, W.B. Gartner, & P. Davidsson (Eds.),Frontiers of entrepreneurship research(pp. 457–470). Babson Park, MA: Center for Entrepreneurial Research, Babson College.

Fabowale, L., Orser, B., & Riding, A. (1995). Gender, structural factors, and credit terms between Canadian small businesses and financial institutions.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,3, 41–65.

Fay, M. & Williams, L. (1993). Gender bias and the availability of business loans. Journal of Business Venturing,8, 363–376.

Foschi, M. (2000). Double standards for competence: Theory and research.Annual Review of Sociology,26, 21–42.

Foschi, M., Lai, L., & Sigerson, K. (1994). Gender and double standards in the assessment of job applicants.

Social Psychology Quarterly,57, 326–339.

Haines, G., Riding, A., & Thomas, R. (1991). Small business bank shopping in Canada.Journal of Banking & Finance,15, 1041–1056.

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1995).Multivariate data analysis. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Holland, J. (1994). Bank lending relationship and the complex nature of bank-corporate relations.Journal of Business Finance & Accounting,21, 367–393.

Ibarra, H. (1992). Homophily and differential returns: Sex differences in network structure and access in an advertising firm.Administrative Science Quarterly,37, 422–447.

Ibarra, H. (1997). Paving an alternative route: Gender differences in managerial networks.Social Psychology Quarterly,60, 91–102.

Kim, P.H. & Aldrich, H.E. (2005). Social capital and entrepreneurship.Foundations and Trends in Entrepre-neurship,1, 1–52.

Kirzner, I. (1982). The theory of entrepreneurship in economic growth. In C. Kent, D. Sexton, & K. Vesper (Eds.),The encyclopedia of entrepreneurship(pp. 272–276). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kon, Y. & Storey, D.J. (2003). A theory of discouraged borrowers.Small Business Economics,21, 37–49.

Laitinen, E. (1991). Financial ratios and different failure processes.Journal of Business Finance & Account-ing,18, 649–673.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J.M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks.

Annual Review of Sociology,27, 415–444.

Nahapiet, J. & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advantage.

Academy of Management Review,23, 242–266.

Nelson, T., Maxfield, S., & Kolb, D. (2009). Women entrepreneurs and venture capital: Managing the shadow negotiation.International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship,1, 57–76.

Orser, B., Riding, A., & Manley, K. (2006). Women entrepreneurs and financial capital.Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,30, 643–665.

Petersen, M. & Rajan, R. (1994). The benefits of firm-creditor relationships: Evidence from small business data.Journal of Finance,49, 3–37.

Petty, J.W. & Upton, N.B. (1997).The entrepreneur and the banker: A comparative study of perceptions. Paper presented at the Annual Babson College-Kauffman Foundation Entrepreneurship Research Conference. Babson Park, MA.

Renzulli, L.A., Aldrich, H., & Moody, J. (2000). Family matters: Gender, networks, and entrepreneurial outcomes.Social Forces,79, 523–546.

Ridgeway, C.L. & Correll, S.J. (2004). Unpacking the gender system: A theoretical perspective on gender beliefs and social relations.Gender & Society,18, 510–531.

Ridgeway, C.L. & Smith-Lovin, L. (1999). The gender system and interaction.Annual Review of Sociology,

25, 191–216.

Riding, A., Haines, G., & Thomas, R. (1994). The Canadian small business-bank interface: A recursive model.

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice,18, 5–24.

Robb, A. & Wolken, J. (2005).Firm, owner and financing characteristics: Differences between female and male-owned small businesses. Working paper, presented at the University of North Carolina Boot camp on Women and Minority Entrepreneurship Research, August, 2005.

Rousseau, D.M., Sitkin, S.B., Burt, R.S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust.Academy of Management Review,23, 405–421.

Rowley, T., Behrens, D., & Krackhardt, D. (2000). Redundant governance structures: An analysis of structural and relational embeddedness in the steel and semiconductor industries.Strategic Management Journal,21, 369–386.

Ruef, M., Aldrich, H., & Carter, N. (2003). The structure of founding teams: Homophily, strong ties and isolation among US entrepreneurs.American Sociological Review,68, 195–222.

Saparito, P., Chen, C., & Sapienza, H. (2004). The role of relational trust in bank-small firm relationships.

Academy of Management Journal,47, 400–410.

Treichel, M. & Scott, J. (2006). Women owned businesses and access to bank credit: Evidence from three surveys since 1987.Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance,8, 51–67.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. (2007).2007 business owner survey. Washington, DC: Bureau of the Census. Available at: http://www.census.gov/econ/sbo/, accessed 17 July 2011.

Uzzi, B. (1999). Embeddedness in the making of financial capital: How social relations and networks benefit firms seeking financing.American Sociological Review,64, 481–505.

Wathne, K., Biong, H., & Heide, J. (2001). Choice of supplier in embedded markets: Relationship and marketing program effects.Journal of Marketing,65, 54–66.

Watson, J., Newby, R., & Mahuka, A. (2009). Gender and the SME “finance gap.”International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship,1, 42–56.

Yli-Renko, H., Autio, E., & Sapienza, H. (2001). Social capital, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge exploitation in young technology-based firms.Strategic Management Journal,22, 587–613.

Patrick Saparito is an assistant professor at Haub School of Business, Saint Joseph’s University, 5600 City Avenue, Philadelphia, PA 19131, USA.

Amanda Elam is President of Galaxy Diagnostics, Inc., and an instructor of Management, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship at North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA.