© The Author 2013. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the American Association for Public Opinion Research. All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oup.com

MeMory, CoMMuniCation, and data Quality

in Calendar interviews

RobeRt F. belli* ipek bilgen taRek al baghal

abstract Calendar instruments are hypothesized to promote data qual-ity through the increased use of retrieval cues and conversational probes intended to clarify meanings. this research explores these hypotheses by examining the associations between retrieval and conversational verbal behaviors and data-quality measures. a verbal behavior coding scheme was applied to transcripts of 165 calendar interviews that collected life-course information on residence, marriage, employment, and unemploy-ment from respondents in the panel Study of income Dynamics (pSiD). Confirmatory factor analyses revealed three latent factors for interview-ers (retrieval probes, rapport behaviors, and convinterview-ersational behaviors intended to satisfy questionnaire objective) and three latent factors for respondents (retrieval strategies, rapport, and conversational behaviors indicative of difficulty being interviewed). Ratios of discrepancies in annual totals between retrospective calendar reports and reports col-lected for up to thirty years in the pSiD over the total number of avail-able years were used as measures of data quality. Regression analyses show that the level of behavior and the level of experiential complexity interact in their effect on data quality. both interviewer and respond-ent retrieval behaviors are associated with better data quality when the retrieval task is more difficult but poorer accuracy when experiential

Robert F. belli is Director of the Survey Research and Methodology program and the gallup Research Center, and professor of psychology, at the University of nebraska–lincoln, lincoln, ne, USa. ipek bilgen is Survey Methodologist ii at noRC at the University of Chicago, Chicago, il, USa. tarek al baghal is Research assistant professor in the Survey Research and Methodology program at the University of nebraska–lincoln, lincoln, ne, USa. this work was supported by the national institute on aging (national institutes of health) [R01ag17977 to R.F.b.] and the national Science Foundation [SeS1132015 to allan McCutcheon]. the contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the national institute on aging, the national institutes of health, or the national Science Foundation. *address correspondence to Robert F. belli, University of nebraska, Survey Research and Methodology program, 201 north 13th St., lincoln, ne 68588-0241, USa; e-mail: bbelli2@unl.edu.

Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 77, Special issue, 2013, pp. 194–219

doi:10.1093/poq/nfs099

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

complexity is low. both interviewer and respondent rapport behaviors are associated with reduced error for complex employment histories but convey mixed results with marriage and unemployment histories. patterns of results for interviewer conversational and respondent dif-ficulty being interviewed behaviors are likewise inconsistent. Results do not completely confirm hypotheses but nevertheless have implica-tions regarding interviewing practice and suggest direcimplica-tions for future research.

introduction

gaining insight into the cognitive and communicative processes that impact the quality of respondent reports has been the main aim of the Cognitive aspects of Survey Methodology (CaSM) movement since its inception (Jabine et al.

1984; Jobe and Mingay 1991). because these cognitive and communicative

processes occur internally,1 their occurrence can be inferred only from observ-able behaviors. Moreover, although the CaSM movement has concentrated mainly on respondent processes, as exemplified by the now classic response process model of comprehension, retrieval, judgment, and response format-ting (Sudman, bradburn, and Schwarz 1996; tourangeau 1984; tourangeau,

Rips, and Rasinski 2000), interviewer cognitive and communicative processes

also play a critical role (Cannell, Miller, and oksenberg 1981; Maynard and

Schaeffer 2002; ongena and Dijkstra 2007). our aim in this paper is twofold.

First, we illustrate that behavior coding provides insights on those cognitive and communicative processes that impact data quality in survey interviews. Second, we seek to demonstrate that there are classes of interviewer and respondent verbal behaviors that are associated with response accuracy in cal-endar interviews (belli 1998; belli, lee, et al. 2004; bilgen and belli 2010).

a ConCeptUal MoDel oF ReSponSe aCCURaCy

in an attempt to grasp the complex interaction between interviewers and respondents, conceptual models have been developed to illustrate interactional problems (ongena and Dijkstra 2007) and how question characteristics impact the quality of interactions and resulting data (Schaeffer and Dykema 2011). in comparison to these approaches, our conceptual model places greater empha-sis on the covert communicative and cognitive processes of interviewers and respondents (see figure 1). as our data have been collected via telephone

1. by internal communicative processes, we mean those processes that permit the overt features of linguistic and paralinguistic expressions to be understood and generated. although young chil-dren and domesticated animals are exposed to adult human language, they lack the internal com-municative processes that are needed to understand and generate linguistic expression at a human adult level.

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

interviewing, our conceptual model is restricted to this mode, although with slight modifications it can be extended to face-to-face interviews.2

although the formal features of the survey questionnaire have an impor-tant indirect impact on response accuracy, the effects are mediated by covert processes and overt behaviors of interviewers and respondents. these formal features include major distinctions such as whether the method is a conven-tional questionnaire or a calendar. in calendar questionnaires, the critical fea-tures include introductory scripts, the domains and their specific timelines, the length of reference period, and the specific information that will satisfy questionnaire objectives (belli and Callegaro 2009; Freedman et al. 1988).

Communicative and cognitive processes are covert in two senses. First, as these processes consist of unspoken tacit knowledge, they largely exist inter-nally to individuals and need to be inferred by others (Maynard and Schaeffer 2002). Second, a substantive proportion of these processes occur noncon-sciously, and hence exist outside individual awareness. among interviewers, Figure 1. Conceptual Model of telephone interviewing dynamics.

2. among these modifications would be the inclusion of nonverbal communicative behaviors, and that respondents may have direct access to formal features of the questionnaire as in show cards or even perhaps by being permitted to directly view question stems and response options.

Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 196

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

their cognitive processing will reflect the degree to which they have incor-porated general and study-specific training, and personal experiences and characteristics unique to them as individuals. in conventional questionnaires, interviewers are trained to interview in a standardized way; in calendar approaches, interviewers are trained to incorporate retrieval probes to assist the autobiographical recall of respondents. What is retained from training will coexist with tacit rules of ordinary conversation and linguistic structure. in our conceptual model, the overt interviewer and verbal and paraverbal behaviors of interviewers—initially in the form of a question that can later be followed in the exchange by probing, verifications, feedback, and other behaviors—are governed by covert processes.

Respondents, of course, can react only to interviewer behavior they can observe, and they will engage in their own covert communicative and cogni-tive processing that will consist of conscious and nonconscious comprehen-sion, retrieval, judgment, and response-formatting strategies and processes. Within these processes are intermixed tacit rules of language and conversation

(Clark and Schober 1992; Sudman, bradburn, and Schwarz 1996). Moreover,

these processes are impacted by personal experiences and characteristics, such as the difficulty of remembering a complex autobiography (burton and blair

1991; Menon 1993), and the cognitive ability and motivation of respondents

to answer questions in an accurate way (krosnick 1991; ongena and Dijkstra 2007). in a paradigmatic question-answering sequence, the respondent’s overt behavior will consist of an immediate adequate (although still poten-tially inaccurate) response (Schaeffer and Maynard 1996). in nonparadigmatic sequences, respondents may ask for clarification, make an evaluative com-ment, provide an inadequate response, or engage in a variety of other behaviors that may require overt interviewer intervention, which will then be mediated by preliminary covert processing on the part of the interviewer. hence, in a cyclic fashion, interviewers and respondents will engage in covert processing and overt verbal behaviors with the intention of terminating in a recordable answer that may be more or less accurate.

in our conceptual model, interviewers may infer whether respondents are motivated, are cooperative, or have the ability to answer questions, and respondents may infer that interviewers may have misunderstood their responses or may have information that would be useful to know to answer questions. Drawing these mutual inferences is one way in which prior ques-tion-response exchanges will have an impact on later ones. Much of what is considered the “common ground” that exists among persons who engage in conversations (Clark and Schober 1992) is drawn from these inferences; spe-cifically for interviewers and respondents, they may develop a largely unspo-ken agreement on how to handle the survey objectives that are being conveyed through the survey instrument. Such agreements may condone a reduction of respondent cognitive effort in the production of responses, and hence encour-age less than optimal answers (houtkoop-Steenstra 2000).

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

VeRbal behaVioR CoDing

a number of validation studies have examined the associations between spe-cific verbal behaviors and response accuracy in retrospective reports from conventional questionnaires. For example, respondent behaviors indicative of cognitive difficulty, such as expressions of uncertainty, inadequate answers, qualified answers, longer response latencies, and saying “don’t know,” are generally associated with decreased accuracy (belli and lepkowski 1996;

Draisma and Dijkstra 2004; Dijkstra and ongena 2006; Dykema, lepkowski,

and blixt 1997). however, measures of cognitive difficulty can in some

con-ditions be associated with increased accuracy, as has been shown from the interactions of cognitive difficulty with respondent age (belli, Weiss, and

lepkowski 1999) and the prevalence of behaviors in respondents’ pasts

(Mathiowetz 1999).

Several explanations may account for these mixed results. Conditions in which cognitive difficulty behaviors are associated with increased accuracy may reflect situations in which either interviewers or respondents recognize that there exists a problem to be overcome; such difficulty, once apparent, may be alleviated by respondents on their own or with interviewer assistance. With regard to interviewers’ providing assistance, however, following up respond-ents’ responses with probing and feedback may also do more harm than good

(belli and lepkowski 1996; belli, lepkowski, and kabeto 2001; Dijkstra

and ongena 2006). nevertheless, the equivocal nature of these results

high-lights that the verbal interactions between interviewers and respondents likely impact response accuracy by each tailoring their turns of speech based on their interpretation of the intended meanings of the other.

latent ConStRUCtS oF behaVioRS

the potential of behavior coding as a method to capture important aspects of interviewing resides on the notion that just as conversational speakers draw inferences regarding the covert processes of others (see figure 1), the sys-tematic examination of the verbal and paraverbal behaviors of interviewers and respondents will provide insights on those covert communicative and cognitive processes that will impact response accuracy. accordingly, because overt behaviors provide clues regarding internal processes, behavior-coding approaches that seek to capture latent constructs as an indication of covert processes are sensible. to date, two studies have associated latent constructs of behaviors, as identified through exploratory factor analyses, with retrospective reporting accuracy. Whereas belli, lepkowski, and kabeto (2001) examined only conventional questionnaire interviews, belli, lee, et al. (2004) examined interviewing from both conventional and calendar questionnaires.

Despite being derived from different questionnaires, different samples, and varied questionnaire methods, both studies uncovered similar “cognitive dif-ficulty” and “rapport” latent constructs. in both cases, cognitive difficulty is

Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 198

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

composed of respondent expressions of uncertainty and inadequate answers. although throughout the history of survey methodology the concept of rap-port has been plagued by differing operational definitions (goudy and potter 1975), the rapport latent construct in both of these behavior-coding studies includes interviewer and respondent laughter and digressions, and among interviewers, unacceptable evaluative feedback (see also houtkoop-Steenstra 2000). Whereas both studies uncovered that a higher prevalence of cognitive difficulty behaviors was associated with poorer accuracy, a higher prevalence of rapport behaviors was associated with poorer accuracy only in belli, lee,

et al. (2004).

CalenDaR inteRVieWing

there is a growing body of literature that details the promise of calendar interviewing in assisting the accuracy of retrospective reports (for reviews,

see belli [forthcoming], table 2; belli and Callegaro [2009]; glasner and

van der Vaart [2009]). behavior-coding studies that have contrasted

cal-endar and conventional questionnaire interviewing have noted important distinctions in the respective prevalence of the behaviors that have been observed, and in associations of behaviors with data quality. these stud-ies are suggestive only that those behaviors that occur more frequently in calendar interviews may underlie processes that are beneficial to response accuracy, as additional evidence is needed to determine whether these pro-cesses actually matter.

With regard to memory processes, calendar interviews have been found to include a greater prevalence of interviewer retrieval probing and spontaneous respondent retrieval strategies (belli, lee, et al. 2004; bilgen and belli 2010). these probes and strategies are labeled parallel when they point to a contem-poraneous event in the past while the respondent is remembering targeted information, and as sequential when they provide cues about what happened earlier or later in time. Sequential behaviors may focus on a) duration, in which an emphasis is place on how long an event took place; or b) timing, in which the attention is placed on when the beginning or ending of a spell of activity took place. in addition, calendar interviews have been found to pro-mote ostensibly beneficial behaviors such as interviewers clarifying intended meanings (see also Schober and Conrad 1997; Suchman and Jordan 1990), alongside ostensibly harmful behaviors such as interviewers providing unac-ceptable evaluative feedback and directive probing (Cannell, Marquis, and

laurent 1977; Cannell, Miller, and oksenberg 1981; Fowler and Mangione

1990).

in their comparison of behavior-accuracy relationships in conventional and calendar questionnaires, belli, lee, et al. (2004) found that latent con-structs behaved differently across methods. Specifically, in comparison to conventional questionnaires, respondents in calendar interviews appear to

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

have benefited more from retrieval cues and to be more resistant to any del-eterious effects of rapport or cognitive problems. these findings provide some support for claims that the data quality of calendar interviews benefits from retrieval cues and conversational behaviors that motivate respondent performance.

the CURRent StUDy

as noted above, the overall results of behavior-coding studies have revealed various patterns with regard to the association of respondent processing dif-ficulty, rapport, and retrieval cues, with response accuracy in calendar inter-views. this lack of consistency may be due largely to behaviors having confounding effects on data quality. For example, rapport can benefit response quality by increasing respondent motivation but can also harm data quality if rapport encourages respondents to ingratiate themselves with their inter-viewers by providing responses that they infer the interinter-viewers would like to hear (Cannell, Miller, and oksenberg 1981; Dijkstra 1987). as for respondents experiencing cognitive difficulty, such difficulty will ordinarily be associated with poorer data quality but such difficulties may also be overcome by atten-tive interviewers who probe so effecatten-tively as to counter its deleterious impact

(belli, lee, et al. 2004).

although more frequent retrieval cues do appear to generally benefit calen-dar interviewing as expected, retrieval cues have not always been found to be beneficial to data quality. the greater reporting of personal landmarks, which are expected to lead to opportunities to draw parallel and sequential associa-tions (belli 1998; belli, Shay, and Stafford 2001), has been observed to have either no or at best a modest positive association with data quality (van der

Vaart and glasner 2007, 2011). Retrieving one event from one’s life may assist

in retrieving other events (belli 1998; brown and Schopflocher 1998), but retrieval of some events may interfere with remembering others (anderson,

bjork, and bjork 1994; Uzer, lee, and brown 2011).

in the current study, our data have been collected from respondents of the panel Study of income Dynamics (pSiD) who have participated in the panel for up to thirty years. they participated in calendar interviews that asked for life-course retrospective reports, and the annual contemporaneous reports of these same panel participants served as validation data for the retrospective reports (for published works of these data, see belli, Smith, et al. 2007; belli, agrawal,

and bilgen 2012). the work of belli, lee, et al. (2004) is the only prior study

that has examined associations between behaviors and data quality in calendar interviews, and the reference period of one to two years in belli, lee, et al.

(2004) is considerably shorter than the reference period for the current study.

hence, we will be able to examine the extent of consistency in results for cal-endar interviews that vary in their lengths of reference periods. in addition, the current study has been designed to overcome a key methodological shortcoming Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 200

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

of the prior work of belli, lee, et al. (2004). the earlier research had a con-siderably cruder unit of analysis—the section or domain of the interview—on which to anchor observed behaviors, which led to uncertainty as to the extent of inter-coder agreement at a turn or utterance level. the behaviors observed in the current study are based on those described by bilgen and belli (2010) for the retrospective conventional and calendar interviews, in which each turn of speech served as the unit of analysis to determine inter-coder reliabilities.

in our behavior-coding approach, following from our conceptual model (see figure 1), we will expose latent constructs that underlie the behaviors via confirmatory factor analyses. We also examine factor structures separately for interviewers and respondents, to expose covert processes for each of these survey-interviewing participants. one of our expectations is that any benefits of calendar interviews in improving autobiographical recall would be medi-ated by experiential complexity. Consider, for example, respondents who are being asked about their life-course employment history; some respond-ents may have never been employed, but others will have been continuously employed during their adult life. For such individuals with little or no expe-riential complexity, the difficulty of the retrieval task would be close to nil; they need only remember that they had never worked or had always worked. now consider other respondents who exhibit experiential complexity by working intermittently. their retrieval task would be considerably more dif-ficult, leading to opportunities for error in retrospective reporting; it has been observed that respondents with more complex histories do report less accu-rately (Dykema and Schaeffer 2000; Mathiowetz and Duncan 1988; Schaeffer 1994). accordingly, one would expect that any beneficial impact of processes that are tied to verbal behaviors, especially as revealed by the increased avail-ability of retrieval cues, would occur most often when one’s experiential past was complex. as the panel data include information on the complexity of respondents’ histories, our models that associate latent behavioral measures with accuracy include interaction terms of the latent constructs with experi-ential complexity.

data and Methods

Data ColleCtion

Computer-assisted telephone interviewing: in this study, our sample3

con-sists of 313 individuals randomly selected from the 2001 panel Study of income Dynamics (pSiD) sample. the respondents in this experiment were

3. this paper analyzes participants from an experiment that consists of a nationwide random sample of 632 pSiD respondents who were interviewed using standardized or calendar interviews. our study focuses on only the respondents who were randomly assigned to the calendar inter-views (for more information, see belli, Smith, et al. [2007]; bilgen and belli [2010]).

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

4. in this experiment, twenty-six interviewers were first matched according to their experience levels and then assigned randomly to each interviewing technique (i.e., standardized conventional and calendar), leaving thirteen interviewers in calendar and thirteen interviewers in conventional interviews (belli, Smith, et al. 2007).

5. appendix a and online appendices b and e (http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/content/71/4/603/ suppl/DC1) of belli, Smith, et al. (2007) detail the calendar instrument development and design and calendar interviewer training.

6. the coders were also transcribers in this study, so they already had some knowledge regard-ing the interviews and the study. Details regardregard-ing the selection of transcribers and coders can be found in bilgen and belli (2010, p. 486).

7. More detailed information regarding the verbal behaviors, their development, and their code descriptions can be found in bilgen and belli (2010; see especially tables 2 and 3).

interviewed via a calendar method embedded within a computer-assisted tel-ephone interviewing (Cati) instrument by thirteen interviewers4 (93-percent cooperation rate, aapoR standard definition 1). the study took place from July to September 2002. the participation criteria were to be a part of a house-hold that was interviewed in every wave, which occurred every year, of the pSiD study at least from 1980 to 1997, and to be a respondent in a minimum of half of the waves in which the household has participated. Sampled individ-uals received $50 for participating. out of 313 interviews, 297 were recorded with the consent of the respondent and 291 audible tapes were transcribed.

the Cati calendar instrument was produced in-house at the University of Michigan. the instrument included a number of domains of interest, with each domain consisting of several timelines.5 We restricted analyses to those respondent reports of past behaviors that had adequate variation in panel and retrospective data for our analytic purposes. these criteria restricted analyses to four timelines in three domains. in the residential domain, we examined the residential changes timeline; in the relationship domain, the marriage timeline was analyzed; and in the labor history domain, employment and unemploy-ment (not working and actively seeking work) timelines were the focus of attention.

Verbal behavior data collection: a coding scheme and coder training

docu-ments were developed by a research group at the University of nebraska– lincoln, which included two of the authors, a ph.D.-level consultant, three graduate students, and an undergraduate student. Five coders6 then were trained, and the coding scheme was improved concurrently during these training sessions via feedback from the coders in training. Due to the budget constraints, a random sample of 165 calendar interviews (57 percent of the transcribed interviews) were verbal behavior coded. the final coding scheme included thirty interviewer and twenty-nine respondent verbal behaviors.7

MethoDS

Item statistics and psychometric analyses: the coding scheme includes

numerous latent verbal behavior components, which are captured by several Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 202

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

correlated verbal behaviors used by the interviewers and respondents during the telephone interviews (bilgen and belli 2010). in order to reduce this wide array of verbal behaviors to a more manageable and limited set, at the first stage of our analyses, we used item statistics and factor analyses to synthesize relevant verbal behavior information, and to eliminate both low-occurrence and irrelevant behaviors, which do not relate to latent traits. our ultimate aim was to construct scales of interviewer and respondent verbal behaviors. our approach included both empirical and theoretical dimensions and used confirmatory factor analyses (CFa) to fit models for both interviewer and respondent behaviors. online appendix a provides greater details on the meth-ods used to identify these latent structures and the fit results.

table 1 describes the behaviors associated with each of the latent factors for

interviewers and respondents, respectively. the interviewer CFa model cap-tures latent factors for retrieval probes, rapport, and conversational probes, and the respondent CFa model points to retrieval strategies, rapport, and difficulty being interviewed as major classes of behavior. the latent factors revealed in both models encapsulate main types of behaviors that have often been the focus of attention in the literature (e.g., belli, lee, et al. 2004; ongena and

Dijkstra 2007; Schaeffer and Dykema 2011).

Variable construction and description of the analyses: at the second stage of

data analyses, we constructed factor score estimates per interview for each of the latent constructs revealed in both the interviewer and respondent CFas, and separately for each of the three domains (residence, relationship, and labor histories). these estimates consisted of calculating z-scores, per inter-view within each domain, of each component behavior, and then summing the

z-scores of each factor’s corresponding behaviors. as the behaviors differed in their frequency of occurrence,8 our approach using z-scores ensured that each behavior contributed equal weight to each latent construct. For each of the timelines, we modeled the effects on the discrepancy between the retrospec-tive and panel reports of the interviewer verbal behavior scales, the respondent verbal behavior scales, and the interaction between respondent verbal behav-ior scales and experiential complexity.

hence, as a first step, we constructed experiential complexity measures from information available in the panel data for residence, marriage, and employ-ment, and unemployment timelines. For each of these timelines, the panel data provided annual self-reports from the years 1968 to 1997 of whether respond-ents moved, were married, were employed, and were unemployed (not work-ing and actively seekwork-ing work). For each interview, the residential experiential complexity measure was constructed as the sum of the number of years a move was indicated in the panel from 1968 to 1997, divided by the number of years

8. online appendix a, tables a1 and a2, provide descriptive statistics on specific behaviors (see the supplementary data online).

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

table 1. interviewer and respondent Factor Models from Confirmatory Factor analyses: Behaviors and their descriptions

panel a: interviewer model

latent factor behavior Description

Retrieval probes parallel probe interviewers probe respondents with an event that is not part of the domain being directly queried to be used as a contemporaneous anchor

Sequential probe interviewers ask respondents within the same domain for the event that followed or preceded the one just discussed

Duration probe interviewers ask respondents how long an event spell took place

Rapport laughter interviewers laugh

Digression interviewers make a comment that is not a direct attempt to satisfy questionnaire objectives

Unacceptable feedback interviewers follow a response with a non-neutral or affectively laden comment

Conversational probes Verification interviewers seek assurance of response correctness Clarification interviewers clarify aspects of question or questionnaire

task-related feedback interviewers notify respondents of an interviewing task that needs to be completed before continuing

Continued

Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal

204

panel b: Respondent model

latent factor behavior Description

Retrieval strategies parallel strategy Respondents spontaneously remember contemporaneous events from an area other than the domain being queried

Duration response Respondents spontaneously report length of spells

Sequential response Respondents spontaneously report event spells that occurred earlier or later in time Use season Respondents use season to time event occurrence

Use age Respondents use their age to time event occurrence

Rapport laughter Respondents laugh

Digression Respondents make a comment that is not a direct attempt to satisfy questionnaire objectives

Difficulty being interviewed Request for clarification Respondents seek clarification on the study or on what is being asked

Correct earlier response Respondents make a correction to a response provided earlier during the interview Don’t know response Respondents indicate not knowing the answer

Disagreement Respondents disagree with any directive probing, verification, or misstatements made by interviewers

note.—adapted from bilgen and belli (2010).

table 1. Continued

, Communication, and Data Quality

205

9. as noted in belli, Smith, et al. (2007), many cases have missing data in certain years. often, such missingness is due to respondents not having joined the panel for a number of years later than 1968. at other times, households did not participate in the panel for certain years, or data were missing in the retrospective calendar reports. in all analyses reported below, if for any given year missing data were observed in the panel or the calendar, that year was treated as missing (i.e., unavailable). of available panel data per respondent.9 hence, the residential experiential complexity measure was a proportion of years for which data were available in which residential changes had been recorded in the panel. the marriage experiential complexity measure consisted of the total number of marriages between the years of 1968 to 1997 divided by the number of available years. employment (i.e., work) complexity was calculated as the proportion of avail-able years in which there was any transition in employment status, and unem-ployment complexity as the proportion of available years in which there was a transition in unemployment status.

as a second step, a discrepancy measure for each timeline per interview was created that consisted of the proportion of the total number of years of avail-able data in which a difference in status between calendar and panel reports occurred out of the number of years of available data (i.e., missing data were not included in either the numerator or denominator). our discrepancy meas-ure is intended to captmeas-ure overall error in the calendar as compared to the contemporaneous panel reports for that specific timeline. as noted below, due to the binomial nature of the dependent variable in the absolute discrepancy models, we fit a logistic regression model via the SaS pRoC genMoD pro-cedure. in the analyses, we used logistic transformation via logit link function and specified dist = binomial in the MoDel statement to allow estimated proportions (i.e., μi or pdiscrepancy = 1) to be distributed between 0 and 1.

as a third step, we examined the association between verbal behaviors and discrepancy and conducted twelve logistic regression models examining interviewer behaviors (one for each of the four timelines and three interviewer verbal behavior scales), and twelve parallel models examining respondent behaviors. For each model, we examined the interaction between each domain-specific verbal behavior scale and experiential complexity one at a time, while controlling for the remaining interviewer verbal behavior scales. each model also included respondent and interviewer characteristics as control variables (respondent age, gender, race, education, and interviewer age, gender, and inter-viewing experience). of the thirteen interviewers, only one was nonwhite, and hence interviewer race was not included. appendix a provides the descriptive statistics for each of these control variables. For each domain, the domain-spe-cific verbal behavior scale included only those behaviors that occurred during interviewing on the specific timeline within that domain. hence, only those verbal behaviors that occurred when the interviewing was targeting residen-tial history were included in models testing residenresiden-tial reporting discrepancy; those that occurred in the relationship history section were tested in examining Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 206

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

discrepancy in reports of marriage; and only those that occurred when labor history was being asked were used in examining discrepancies in reports of employment and unemployment. accordingly, and for example, the interac-tion of interviewer retrieval probing and residence experiential complexity in predicting residential discrepancy is examined via the following model:

LN[Prd/(1 – Prd)] = β0+ β1(I’werRetrieval)R+ β2(I’werRapport)R+ β3(I’wer

ConvProbes)R+ β4(Experiential Complexity)R+ β5(R’dent Age) + β6(R’dent

Gender) + β7(R’dent Race) + β8(R’dent Educ) + β9(I’wer Age) + β10(I’wer

Gender) + β11(I’wer Experience) + β12 (I’werRetrieval*Experiential

Complexity)R+ e, in which R = Residence and rd = Residence Discrepancy.

Similarly, the spontaneous respondent retrieval strategies and residence expe-riential complexity interaction is examined via the following model:

LN [Prd/(1 – Prd)] = β0+ β1(R’dentRetrieval)R+ β2(R’dentRapport)R+ β3

(I’wingDiff)R+ β4(Experiential Complexity)R+ β5(R’dent Age) + β6(R’dent

Gender) + β7(R’dent Race) + β8(R’dent Educ) + β9(I’wer Age) + β10(I’wer

Gender) + β11(I’wer Experience) + β12 (R’dentRetrieval*Experiential

Complexity)R+ e, in which R = Residence and rd = Residence Discrepancy.

as a fourth step, we analyzed the cumulative effect of interviewer and respondent verbal behaviors in interaction with experiential complexity in pre-dicting discrepancy. For the cumulative analyses, we calculated latent variable estimates by summing the domain-specific factor estimates from the earlier and current domains; this approach ensured an equal weight of each domain’s contribution to each estimate. For instance, in order to create the cumulative interviewer retrieval behavior for labor domain, we summed, per interview, the factor score estimates for retrieval behavior from residence, marriage, and labor domains. because residence is asked about first, cumulative analyses are restricted to the marriage, employment, and unemployment domains. in the cumulative logistic regression analyses, we examined the interaction of each of the cumulative interviewer verbal behavior estimates and experiential com-plexity on discrepancy (i.e., measurement error) in nine separate models (for each of the three domains and three cumulative interviewer verbal behavior estimates), while controlling for the remaining cumulative interviewer verbal behavior estimates. the same approach was used with respondent behaviors. the logic underlying these cumulative analyses is that behaviors that occur in prior sections may have a cumulative impact on reporting accuracy as inter-viewers and respondents continue to assess the nature of their interaction during the entire interview (see figure 1). an alpha of 0.10 was set for the regression analyses, as we were interested in revealing consistent patterns of results instead of seeking the confirmation of single results.

For any of these noncumulative and cumulative models in which a significant interaction was not observed, we tested for main effects in models separately by

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

domain and by interviewer and respondent behaviors. each of these main effects models included all three terms that represented the interviewer and respondent factors, respectively.10 For those models in which a significant interaction was found, we conducted a regions of significance (RoS) analysis to determine at which percentiles of the experiential complexity distribution, if any, there were significant differences of behaviors on discrepancies (at α = 0.10).11although much of the work on RoS has examined linear regression-type models (bauer

and Curran 2005), as the log link model function linearizes the model in the

logs odds metric, the same region of significance method may be used for a log link model as with a linear model (hayes and Matthes 2009).

results

DeSCRiptiVe ReSUltS

Due to processing errors, the loss of data occurred for nine cases.12 hence, of the 165 behavior-coded interviews, results were conducted on the remain-ing 156 cases. the descriptive statistics for the experiential complexity and

10. all of our significance tests were adjusted taking into account clustering due to interview-ers. Design effects (deff), i.e., the inflation of variances due to interviewer effects, were calcu-lated for dependent variables in one-way analyses of variance of each of the dependent variables with interviewers as the factor. the calculated design effects were Moves = 1.64, Marriage = 2.00, employment = 1.45, and Unemployment = 0.97. the covariance matrices of all models were inflated by the respective design effects calculated for each dependent variable; for example, all variance and covariance estimates for marriage models were multiplied by 2. Since the design effect for unemployment was less than one, no inflationary factor was used. another consideration in our modeling is that accounting for interviewer effects requires that we estimate degrees of freedom based on the number of interviewers, which is smaller than the number of respondents. accordingly, we calculated our degrees of freedom to the number of interviewers – 1 = 12, which follows what would be done in a cluster sample survey with no strata using a taylor series approximation (lee and Forthofer 2006). Using these inflated covariance matrices and 12 df, appropriate standard errors and p-values were calculated for all interaction and main effect regression coefficients.

11. For an interaction effect in a regression, it may be examined whether the effect of one variable (focal variable) varies as a function of a second predictor (moderator variable). the focal vari-ables are the verbal behaviors, and the moderator is experiential complexity. to find the regions of significance for the interaction between the two, with 12 df and using p < 0.10 as the threshold, the following calculation is used:

Varβ Cov Expeerinetail Complexity) Var( )(Experiential Complexity) ,

+ β1

2

where βF is the coefficient for the main effect of the focal variable (the verbal behavior), β1 is the coefficient for the interaction between the focal (verbal behavior) and moderator (difficulty), and Experiential Complexity is the value for the experiential complexity variable. the goal is to find values of difficulty that satisfy the equation (i.e., at or greater than ±1.78).

12. For four of these cases, the calendar Cati instrument did not preserve the collected data. For five of these cases, the case identification numbers from transcription and coding did not match any case identification numbers in the calendar data files.

Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 208

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

discrepancy measures for each timeline are presented in table 2.13 as each mean is based on a proportion calculated for each case on the number of occur-rences divided by the number of years of available data, each of the means can be converted to percentages. For example, a mean of 0.168 indicates that on average respondents reported a change in residence in 16.8 percent of the available years. Moreover, a mean of 0.083 in table 2 indicates that respond-ents in the panel data had an average of 8.3 percent of their available years indicating a transition between employment and a state of not being employed or vice versa. likewise, across cases, the mean percentage of available years in which there was a discrepancy between panel and calendar reports varied between 7.1 and 12.4 percent, depending on the timeline.14

logiStiC MoDelS on DiSCRepanCy

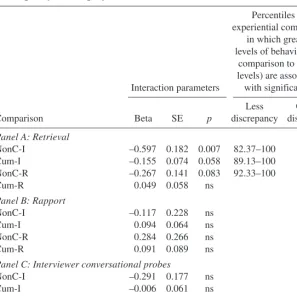

listwise deletion in the logistical modeling led to a loss of three cases due to missing data on respondent education, and hence results are based on 153 interviews. tables 3–6 provide significant behavior and difficulty interactions table 2. Means, standard deviations, and Percent of Zero Cases per domain for experiential Complexity and discrepancy

Domain Measure

changes 0.168 0.158 17.31 0.124 0.123 26.28

Marriage number 0.045 0.025 7.69 0.071 0.166 60.90

employment transitions 0.083 0.097 19.87 0.104 0.201 50.64

Unemployment transitions 0.126 0.131 34.62 0.111 0.153 35.90

13. appendix b provides information on the frequency and percentage of interviews conducted by each interviewer on the 156 cases.

14. one reviewer of an earlier version of this paper questioned the utility of the discrepancy measure by correctly noting that failing to retrospectively report an annual event observed in the panel would result in one discrepancy, but retrospectively reporting an event in a year that dif-fered from that in the panel would result in two discrepancies. First, an advantage of the discrep-ancy measure is that it is sensitive to several errors, including omission, commission, and dating. Second, it is not possible with our data to determine whether a reported event is the event that exists in the panel even if the events are misaligned by one year. third, this issue becomes less of a concern in the marriage and employment timelines as marriages, and periods of employment, usually span more than one year. Fourth, although this issue is more of a concern for residential changes and unemployment, as with each, events are likely to occur in discrete years, there are reasons as to why this issue is not very challenging. as residential changes revealed only mod-est underreporting, the discrepancy measure would be most sensitive to detecting dating errors. although there was more severe underreporting in unemployment, we found that out of a total of 450 discrepancies, only seven were misaligned by one year.

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

on the absolute discrepancies in the residence, marriage, employment, and unemployment timelines, respectively. these tables report regression param-eters and observed regions of significance in the percentiles of experiential complexity scores in which greater levels of behaviors are associated with lower or higher levels of discrepancy. For example, table 3 reveals that higher levels of noncumulative respondent retrieval is associated with less discrep-ancy at high percentiles of experiential complexity (91.97 to the 100th per-centile), and that greater discrepancy at the low percentiles of experiential complexity (0 to 79.95th percentiles) is observed with noncumulative inter-viewer retrieval. each table consists of separate panels devoted to interinter-viewer and respondent retrieval behaviors (interviewer probing and respondent strate-gies, respectively), interviewer and respondent rapport behaviors, interviewer conversational probing behaviors, and respondent difficulty being interviewed behaviors.

tables 3 and 5 illustrate two similar patterns of significant associations

for the residence and employment timelines. First, greater levels of verbal behaviors are associated with less discrepancy between retrospective and panel reports at higher percentiles of experiential complexity, which is the table 3. logistic regression Coefficients for the interaction of Behaviors and experiential Complexity on discrepancy, and Percentiles of experiential Complexity associated with significantly less and Greater discrepancy: residence

Panel D: Respondent difficulty being interviewed

Respondent –0.332 0.117 0.015 0–91.71

Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 210

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

only pattern observed in unemployment (table 6). Second, greater levels of verbal behaviors are associated with a greater discrepancy at lower percen-tiles of experiential complexity. both patterns are observed in employment with noncumulative and cumulative interviewer retrieval, and with cumula-tive respondent retrieval (table 5). the first pattern alone is observed with respondent retrieval in residence (table 3), and in unemployment with noncu-mulative and cunoncu-mulative interviewer retrieval and noncunoncu-mulative respondent retrieval (table 6); it is also observed with three of the four interaction sig-nificance tests for rapport in employment (table 5). the second pattern alone occurs with interviewer retrieval and conversational probes, and respond-ent difficulty being interviewed in residence (table 3). Significant main effects were also observed for some of the unemployment models in which table 4. logistic regression Coefficients for the interaction of Behaviors and experiential Complexity on discrepancy, and Percentiles of experiential Complexity associated with significantly less and Greater discrepancy: Marriage

nonC-R –3.268 1.413 0.039 91.73–100 0–77.30

Cum-R –0.667 0.771 ns

Panel B: Rapport

nonC-i 0.199 0.884 ns

Cum-i 1.174 0.594 0.072 0–46.38

nonC-R –2.798 1.333 0.058 99.26–100 0–18.83

Cum-R –0.027 0.779 ns

Panel C: Interviewer conversational probes

nonC-i 2.616 0.985 0.021 0–69.82 98.28–100

Cum-i 2.506 0.679 0.003 0–54.12 91.73–100

Panel D: Respondent difficulty being interviewed

nonC-R 2.326 1.089 0.054 85.72–100

Cum-R 2.268 0.808 0.016 0–48.27 91.40–100

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

the behavior by complexity interaction is not significant: Verbal behav-iors are associated with greater discrepancy for noncumulative (β = 0.099, Se = 0.028, p < 0.004) and cumulative (β = 0.018, Se = 0.009, p = 0.069) interviewer rapport.

as for the marriage timeline (table 4), with the exception of noncumulative respondent retrieval and rapport, the dominant patterns of significant interac-tion effects are opposite to those observed with residence, employment, and unemployment: higher levels of behaviors are associated with more discrep-ancy at higher percentiles of experiential complexity, and they are associated with less discrepancy with lower complexity. in addition, a higher level of noncumulative interviewer retrieval is associated with greater discrepancy (β = 0.153, Se = 0.038, p < 0.015).

table 5. logistic regression Coefficients for the interaction of Behaviors and experiential Complexity on discrepancy, and Percentiles of experiential Complexity associated with significantly less and Greater discrepancy: employment

nonC-i –0.666 0.224 0.012 97.94–100 0–79.28

Cum-i –0.341 0.101 0.006 96.18–100 0–84.17

nonC-R –0.424 0.276 ns

Cum-R –0.217 0.094 0.040 93.84–100 0–33.55

Panel B: Rapport

Panel D: Respondent difficulty being interviewed

nonC-R –0.066 0.176 ns

Cum-R 0.031 0.064 ns

Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 212

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

discussion

the StRUCtURe oF VeRbal behaVioRS anD Data QUality

We expected the verbal behaviors that have been observed to be more prevalent in calendar interviews—especially those that involve retrieval and clarification processes— to be associated with better data quality. our results provide only limited support for the expected benefits of retrieval behaviors. among the supportive evidence is that, in all eight tests that provided significant results for retrieval behaviors during circumstances in which respondents’ histories are more complicated and hence lead to a relatively difficult retrieval task, all eight reveal that an increased use of retrieval behaviors is associated with better data quality. overall, these findings are consistent with the notion that table 6. logistic regression Coefficients for the interaction of Behaviors and experiential Complexity on discrepancy, and Percentiles of experiential Complexity associated with significantly less and Greater discrepancy: unemployment

Panel D: Respondent difficulty being interviewed

nonC-R –0.137 0.171 ns

Cum-R 0.005 0.064 ns

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

engaging in effortful retrieval will be beneficial in calendar interviews among respondents who have complicated experiential histories that are more dif-ficult to recall.

however, evidence also points to the unexpected finding that, when retrieval is not very difficult at all because of an uncomplicated history, the greater use of retrieval probes and strategies decreases data quality. perhaps some respondents who are exposed to minimal retrieval probes and engage in mini-mal retrieval strategies are able to automatically remember their uncompli-cated pasts, whereas other respondents who have difficulty remembering their uncomplicated pasts are exposed to numerous unsuccessful retrieval cues. also contrary to expectation is that, in retrospective reports of marriage, interviewer retrieval probing is associated with less accuracy regardless of complexity.

interviewer conversational probes have mixed effects on data quality, and it is best to consider each timeline separately. in employment, conversational probes assist data quality when the retrieval task is difficult. in residence, con-versational probes harm data quality when the retrieval task is easy, and in marriage, they harm data quality when the retrieval task is difficult but help accuracy when the retrieval task is easy. Similar mixed patterns associated with the residence and marriage timelines are observed with respondent dif-ficulty being interviewed; the behaviors that compose this measure have occa-sionally revealed mixed results in the literature (belli, Weiss, and lepkowski

1999; belli, lee, et al. 2004; Mathiowetz 1999). it is difficult to develop

rea-sonable explanations based on mixed results, but the fact that various topics and situations are impacted differently points to the possibility that at times interviewers are able to assist respondents when they are expressing difficulty in a retrieval task, but at other times the assistance of interviewers only makes matters worse.

our results for rapport behaviors are also mixed, which is not unexpected, as prior research has been equivocal about the impact that rapport may have on data quality (belli, lepkowski, and kabeto 2001; belli, lee, et al. 2004,

henson, Cannell, and lawson 1976; Weiss 1968; Williams 1968). our results

may provide at least a partial explanation for these mixed results. according to the motivation/ingratiation model of Dijkstra (1987), rapport increases respondent motivation as well as the tendency for the respondent to ingratiate him- or herself with the interviewer. With employment, rapport may lead to an increased motivation on the part of respondents to report accurately, which is consistent with the observation that in employment, increased rapport is associated with better data quality when the retrieval task is more difficult. but our results also point to the possibility that rapport is at times associated with an ingratiation process. having been frequently married may be seen by some respondents as socially undesirable and difficult to admit. When respondents initiate rapport (and retrieval), marriages are reported more accurately when their occurrence is more frequent, indicating that they may be ingratiating interviewers by admitting their marriages within the context of humor and Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 214

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

storytelling. however, when interviewers engage in frequent rapport (and retrieval probing) behaviors, married respondents may feel uncomfortable and, in an attempt to ingratiate interviewers, report their marriages less adequately. the impact of rapport on unemployment is a bit more difficult to explain. although one might expect that frequent unemployment would be undesir-able to report, increased rapport is associated with less accuracy regardless of whether unemployment occurred frequently or infrequently.

iMpliCationS

our results reveal that patterns of associations between verbal behaviors and data quality depend not only on the inherent difficulty of retrospective reports, but also on which specific information is being queried. although we are con-fident, as illustrated in our conceptual model (see figure 1), that latent verbal behaviors reflect specific processes, one of the more challenging implications of our results is that these latent verbal behaviors appear to be ambiguous in terms of the exact cognitive and conversational processes that underlie their occurrence. in other words, each of the latent constructs of verbal behaviors is likely reflecting several specific processes.

Despite these complications, insights are procured. as one example, retrieval behaviors appear to be helpful when the retrieval task is more dif-ficult, but also appear to backfire when the retrieval task is easier. as another example, rapport is usually helpful but may be detrimental if the informa-tion being queried is sensitive in nature. Such insights provide potential direc-tions for calendar design and interviewer training. it may be advantageous, for example, to screen respondents on how often they have experienced behaviors with interviewers using retrieval probing only in those instances in which the experienced behaviors are likely to have occurred often. interviewers who seek the development of close interpersonal rapport may be advantageous only for questionnaires that minimize the asking of sensitive information, or when they can capture reciprocity of friendliness on the part of respondents.

admittedly, the insights we have gained are limited because cognitive and communication processes can be observed only indirectly. in addition to the mainly quantitative approach we have taken, insights into the impact of the latent constructs we have identified may benefit by the inclusion of quali-tative-oriented approaches that emphasize contextualized and interactional analyses. hence, our research provides a foundation upon which this future work can be built.

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

appendix a

descriptive statistics for Control variables

panel a: Continuous Characteristics

n Mean S.D.

Respondent years of education 153 13.15 2.57

Respondent age 156 62.40 11.77

interviewer age 13 46.38 14.13

panel b: Count Characteristics

n percent

Respondents—white 129 82.69

Respondents—non-white 27 17.31

Respondents—male 85 54.49

Respondents—female 71 45.51

interviewers—male 3 23.10

interviewers—female 10 76.90

interviewers—less than one year’s experience 3 23.10

interviewers—one or more years’ experience 10 76.90

appendix B

Frequency and Percentage of interviews administered by each interviewer

interviewer Frequency percent

a 6 3.85

b 14 8.97

C 10 6.41

D 16 10.26

e 10 6.41

F 15 9.62

g 19 12.18

h 9 5.77

i 16 10.26

J 7 4.49

k 12 7.69

l 6 3.85

M 16 10.26

total 156 100.02

supplementary data

Supplementary data are freely available online at http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/. Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 216

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

references

anderson, Michael C., Robert a. bjork, and elizabeth l. bjork. 1994. “Remembering Can Cause Forgetting: Retrieval Dynamics in long-term Memory.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 20:1063–87.

bauer, Daniel J., and patrick J. Curran. 2005. “probing interactions in Fixed and Multilevel Regression: inferential and graphical techniques.” Multivariate Behavioral Research 40:373–400.

belli, Robert F. 1998. “the Structure of autobiographical Memory and the event history Calendar: potential improvements in the Quality of Retrospective Reports in Surveys.” Memory 6:383–406.

———. Forthcoming. “autobiographical Memory Dynamics in Survey Research.” in Sage Handbook of Applied Memory, edited by t. J. perfect and D. S. lindsay. thousand oaks, Ca: Sage.

belli, Robert F., Sangeeta agrawal, and ipek bilgen. 2012. “health Status and Disability Comparisons between Cati Calendar and Conventional Questionnaire instruments.” Quality & Quantity 46:813–28.

belli, Robert F., and Mario Callegaro. 2009. “the emergence of Calendar interviewing: a theoretical and empirical Rationale.” in Calendar and Time Diary Methods in Life Course Research, edited by R. F. belli, F. p. Stafford, and D. F. alwin, 31–52. thousand oaks, Ca: Sage.

belli, Robert F., eun ha lee, Frank p. Stafford, and Chia-hung Chou. 2004. “Calendar and Question-list Survey Methods: association between interviewer behaviors and Data Quality.” Journal of Official Statistics 20:185–218.

belli, Robert F., and James M. lepkowski. 1996. “behavior of Survey actors and the accuracy of Response.” health Survey Research Methods: Conference proceedings, 69–74. DhhS publication no. (phS) 96–1013.

belli, Robert F., James M. lepkowski, and Mohammed U. kabeto. 2001. “the Respective Roles of Cognitive processing Difficulty and Conversational Rapport on the accuracy of Retrospective Reports of Doctor’s office Visits.” in Seventh Conference on Health Survey Research Methods, edited by M. l. Cynamon and R. a. kulka, 197–203. DhhS publication no. (phS) 01-1013. hyattsville, MD: U.S. government printing office.

belli, Robert F., William l. Shay, and Frank p. Stafford. 2001. “event history Calendars and Conventional Questionnaire Surveys: a Direct Comparison of interviewing Methods.” Public Opinion Quarterly 65:45–74.

belli, Robert F., lynette M. Smith, patricia M. andreski, and Sangeeta agrawal. 2007. “Methodological Comparisons between Cati event history Calendar and Standardized Conventional Questionnaire instruments.” Public Opinion Quarterly 71:603–22.

belli, Robert F., paul S. Weiss, and James M. lepkowski. 1999. “Dynamics of Survey interviewing and the Quality of Survey Reports: age Comparisons.” in Cognition, Aging, and Self-Reports, edited by n. Schwarz, D. park, b. knäuper, and S. Sudman, 303–25. philadelphia: taylor & Francis.

bilgen, ipek, and Robert F. belli. 2010. “Comparisons of Verbal behaviors between Calendar and Standardized Conventional Questionnaires.” Journal of Official Statistics 26:481–505. brown, norman R., and Donald Schopflocher. 1998. “event Clusters: an organization of personal

events in autobiographical Memory.” Psychological Science 9:470–75.

burton, Scot, and edward blair. 1991. “task Conditions, Response Formulation processes, and Response accuracy for behavioral Frequency Questions in Surveys.” Public Opinion Quarterly 55:50–79.

Cannell, Charles F., kent h. Marquis, and andré laurent. 1977. “a Summary of Studies of interviewing Methodology.” Vital and Health Statistics 69, Series 2.

Cannell, Charles F., peter V. Miller, and lois oksenberg. 1981. “Research on interviewing techniques.” in Sociological Methodology, edited by S. leinhardt, 389–437. San Francisco: Jossey-bass.

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

Clark, herbert h., and Michael F. Schober. 1992. “asking Questions and influencing answers.” in Questions about Questions, edited by J. M. tanur, 15–48. new york: Russell Sage Foundation. Dijkstra, Wil. 1987. “interviewing Style and Respondent behavior: an experimental Study of the

Survey interview.” Sociological Methods & Research 16:309–34.

Dijkstra, Wil, and yfke ongena. 2006. “Question-answer Sequences in Survey interviews.” Quality & Quantity 40:983–1011.

Draisma, Stasja, and Wil Dijkstra. 2004. “Response latency and (para)linguistic expressions as indicators of Response error.” in Methods for Testing and Evaluation of Survey Questionnaires, edited by S. presser, J. M. Rothgeb, M. p. Couper, J. t. lessler, e. Martin, J. Martin, and e. Singer, 131–47. hoboken, nJ: Wiley.

Dykema, Jennifer, James M. lepkowski, and Steven blixt. 1997. “the effect of interviewer and Respondent behavior on Data Quality: analysis of interaction Coding in a Validation Study.” in Survey Measurement and Process Quality, edited by l. lyberg, p. biemer, M. Collins, e. de leeuw, C. Dippo, n. Schwarz, and D. trewin, 287–310. new york: J. W. Wiley and Sons. Dykema, Jennifer, and nora Cate Schaeffer. 2000. “events, instruments, and Reporting errors.”

American Sociological Review 65:619–29.

Fowler, Floyd J. Jr., and thomas W Mangione. 1990. Standardized Survey Interviewing. newbury park, Ca: Sage.

Freedman, Deborah, arland thornton, Donald Camburn, Duane alwin, and linda young-DeMarco. 1988. “the life history Calendar: a technique for Collecting Retrospective Data.” in Sociological Methodology 18, edited by C. C. Clogg, 37–68. San Francisco: Jossey-bass. glasner, tina, and Wander van der Vaart. 2009. “applications of Calendar instruments in Social

Surveys: a Review.” Quality & Quantity 43:333–49.

goudy, Willis J., and harry R. potter. 1975. “interview Rapport: Demise of a Concept.” Public Opinion Quarterly 39:529–43.

hayes, andrew F., and Jörg Matthes. 2009. “Computational procedures for probing interactions in olS and logistic Regression: SpSS and SaS implementations.” Behavior Research Methods 41:924–36.

henson, Ramon, Charles F. Cannell, and Sally lawson. 1976. “effects of interviewer Style on the Quality of Reporting in a Survey interview.” Journal of Psychology 93:221–27.

houtkoop-Steenstra, hanneke. 2000. Interaction and the Standardized Survey Interview. Cambridge, Uk: Cambridge University press.

Jabine, thomas b., Miron l. Straf, Judith M. tanur, and Roger tourangeau, eds. 1984. Cognitive Aspects of Survey Methodology: Building a Bridge between Disciplines. Washington, DC: national academy press.

Jobe, Jared b., and David J. Mingay. 1991. “Cognition and Survey Measurement: history and overview.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 5:175–92.

krosnick, Jon a. 1991. “Response Strategies for Coping with the Cognitive Demands of attitude Measures in Surveys.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 5:213–36.

lee, eun Sul, and Ronald n. Forthofer. 2006. Analyzing Complex Survey Data. thousand oaks, Ca: Sage.

Mathiowetz, nancy a. 1999. “Response Uncertainty as indicator of Response Quality.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 11:289–96.

Mathiowetz, nancy a., and greg J. Duncan. 1988. “out of Work, out of Mind: Response errors in Retrospective Reports of Unemployment.” Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 6:221–29.

Maynard, Douglas W., and nora Cate Schaeffer. 2002. “Standardization and its Discontents.” in Standardization and Tacit Knowledge, edited by D. W. Maynard, h. houtkoop-Steenstra, n. C. Schaeffer, and J. van der Zouwen, 3–45. new york: Wiley.

Menon, geeta. 1993. “the effects of accessibility of information in Memory on Judgments of behavioral Frequencies.” Journal of Consumer Research 20:431–40.

ongena, yfke p., and Wil Dijkstra. 2007. “a Model of Cognitive processes and Conversational principles in Survey interview interaction.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 21:145–63.

Belli, Bilgen, and Al Baghal 218

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/

Schaeffer, nora Cate. 1994. “errors of experience: Response errors in Reports about Child Support and their implications for Questionnaire Design.” in Autobiographical Memory and the Validity of Retrospective Reports, edited by n. Schwarz and S. Sudman, 142–60. new york: Springer-Verlag.

Schaeffer, nora Cate, and Jennifer Dykema. 2011. “Response 1 to Fowler’s Chapter: Coding the behavior of interviewers and Respondents to evaluate Survey Questions.” in Question Evaluation Methods: Contributing to the Science of Data Quality, edited by J. Madans, k. Miller, a. Maitland, and g. Willis, 23–39. new york: Wiley.

Schaeffer, nora Cate, and Douglas W. Maynard. 1996. “From paradigm to prototype and back again: interactive aspects of Cognitive processing in Standardized Survey interviews.” in Answering Questions: Methodology for Determining Cognitive and Communicative Processes in Survey Research, edited by n. Schwarz and S. Sudman, 65–88. San Francisco: Jossey-bass.

Schober, Michael F., and Frederick g. Conrad. 1997. “Does Conversational interviewing Reduce Survey Measurement error?” Public Opinion Quarterly 61:576–602.

Suchman, lucy, and brigitte Jordan. 1990. “interactional troubles in Face-to-Face interviews.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 85:232–41.

Sudman, Seymour, norman M. bradburn, and norbert Schwarz. 1996. Thinking about Answers: The Application of Cognitive Processes to Survey Methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-bass. tourangeau, Roger. 1984. “Cognitive Science and Survey Methods.” in Cognitive Aspects of

Survey Methodology: Building a Bridge between Disciplines, edited by t. b. Jabine, M. l. Straf, J. M. tanur, and R. tourangeau, 73–100. Washington, DC: national academy press. tourangeau, Roger, lance J. Rips, and kenneth Rasinski. 2000. The Psychology of Survey

Response. Cambridge, Uk: Cambridge University press.

Uzer, tugba, peter J. lee, and norman R. brown. 2011. “the impact of Cue Repetition on autobiographical Memory Retrieval.” poster presented at the 52nd annual Meeting of the psychonomic Society, Seattle, Wa, USa.

van der Vaart, Wander, and tina glasner. 2007. “the Use of landmark events in ehC interviews to enhance Recall accuracy.” Report commissioned by the U.S. bureau of the Census. Washington, DC.

———. 2011. “personal landmarks as Recall aids in Surveys.” Field Methods 23:37–56. Weiss, Carol h. 1968. “Validity of Welfare Mothers’ interview Responses.” Public Opinion

Quarterly 32:622–33.

Williams, J. allen Jr. 1968. “interviewer Role performance: a Further note on bias in the information interview.” Public Opinion Quarterly 32:287–94.

at Mahidol University, Faculty of Medicine, Siriraj Hospital on March 16, 2015

http://poq.oxfordjournals.org/