CORRESPONDENCE Prof Gregory Y H Lip,

University of Birmingham Centre for Cardiovascular Sciences, City Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom

g.y.h.lip@bham.ac.uk

Sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb. The author(s) maintained full control of the content and writing of the manuscript

ISSN 2042-4884

Clinical implications and issues in everyday management

NOACs offer efficacy, safety and convenience as thromboprophylaxis in AF patients. Moreover the lack of laboratory monitoring or dose adjustments, as well as the few food and drug- drug interactions, render NOACs attractive alternatives to warfarin in clinical practice especially in patients with unstable INR (TTR >70%).In elderly people NOACs are associated with lower rates of major bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage, compared with warfarin, which represents an important advantage of NOACs since 45% of the patients diagnosed with AF are older than 75 years [40].

Novel Pharmacotherapies for the Prevention of Stroke or

Systemic Embolism in Adults with Non-valvular Atrial Fibrillation -

Part 2

Christos Dresios , MD & Gregory Y H Lip, MD

University of Birmingham Centre for Cardiovascular Sciences

Received: 28/8/13, Reviewed: 28/2/14, Accepted: 28/3/14

Key words: atrial fibrillation, stroke prevention, apixaban DOI: 10.5083/ejcm.20424884.116

328 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICINE VOL III ISSUE I

This article is a continuation of Novel Pharmacotherapies for the Prevention of Stroke or Systemic Embolism in Adults with Non-valvular Atrial Fibrillation - Part 1.

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICINE 2014;3(1):318-327

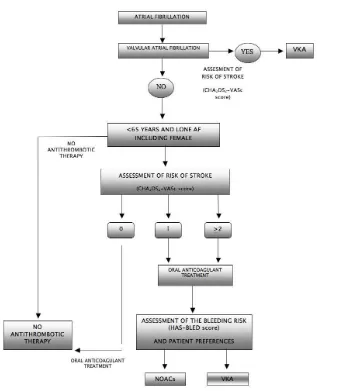

An algorithm illustrating the choice of anti-thrombotic therapy in patients with AF is shown in Figure 1.

Despite the fact that NOACs have gain clinical approval and are currently increasingly available for the prevention of stroke or systemic embo-lism in patients with non valvular AF, there are important clinical considerations in relation to their use in certain clinical circumstances.

NOACs in the elderly

The risk of stroke and bleeding complications increases with age. Despite the fact that NOACs have a favourable risk-benefit profile in all age groups, some caution is required in order to reduce not only the thromboembolic risk but also the bleeding risk. Indeed, in elderly pa-tients receiving NOACs close monitoring of re-nal function is of great importance, particularly relevant for dabigatran which is mainly renally excreted. Thus, in patients receiving dabigatran renal function should be evaluated at least once every 6 months. Also, renal function should be closely monitored during pathological condi-tion that could potentially have impact on cre-atinine clearance.

Elderly patients have higher plasma concentra-tions of dabigatran compared to younger pa-tients, in patients aged 80 years and above treat-ed with dabigatran, dosing should be rtreat-eductreat-ed to 110mg twice daily. Although dose adjust-ment is not routinely recommended in elderly patients treated with rivaroxaban, age related changes in renal function should be evaluated and consequently a dose adjustment should be considered. The benefits of apixaban compared to warfarin in prevention of stroke with lower rates of major bleeding are consistent across major subgroups, including the elderly. In pa-tients receiving apixaban dosing adjustment is not required unless the criteria for dose reduc-tion previously discussed are met.

Missed dose

Due to the fact that NOACs have relatively short half-lives adherence to the therapeutic scheme is of crucial importance. Indeed, the omission of a single dose could be associated with increased thromboembolic risk.

Dabigatran and apixaban should be taken regularly twice a day, at approximately 12 hour intervals. When the prescribed dose of the anticoagulant drug is not received at the scheduled time, the dose should be taken as soon as possible on the same day. A missed dose of dabigatran or apixaban may be administered till 6 h after the scheduled intake. If that is not possible, the missed dose should be skipped and the next scheduled dose should be received as rec-ommended. In any case, the dose should not be doubled within the same day to make up for a missed dose.

On the other hand, patients who miss a dose of rivaroxaban should receive the missed dose till 12 h after the scheduled intake and con-tinue on the following day with the once daily administration as recommended. Similarly to other NOACs, the dose should not be doubled within the same day to make up for a missed dose.

Overdose

Overdose of NOACs may increase systemic exposure and lead to hemorrhagic complications. In the absence of specifics antidotes able to reverse anticoagulant effects of NOACs the management of NOACs overdose becomes a challenging task for physicians.

Due to the short half life of NOACs the interruption of anticoagulant treatment and supportive treatment is the initial approach. Admin-istration of activated charcoal to reduce absorption between 2 and 6 hours after ingestion of NOACs could be useful in the manage-ment of overdose. Where bleeding is evident, non-specific reversal agents (eg prothrombin complex concentrates, rFVIIa etc) and (for dabigatran) haemodialysis should be considered.

Renal impairment

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with increased risk of both thrombo-embolic and bleeding complication in patients with AF [41,42]. Although NOACs represent a reasonable option for

an-ticoagulant treatment in AF patients with mild or moderate renal impairment, their use in severe renal impairment (CrCl<30ml/min) is not recommended [28].

There is lack of evidence in regard to the use of NOACs in patients on dialysis or in patients that are likely to undergo dialysis in the near future. Thus, NOACs are not recommended in patients on he-modialysis and vitamin K antagonists are considered to represent the most appropriate anticoagulant therapy in this case.

330 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICINE VOL III ISSUE I Currently there is no evidence suggesting which could be the most

effective NOAC for treating patients with moderate renal failure. In addition, the need of dose adjustment should be carefully assessed in the management of patients with renal impairment. All patients that are considered eligible to receive NOACs should undergo not only baseline but also periodic assessment of their renal function. In particular, renal function should be evaluated annually in patients with normal or CKD stage I–II (CrCl ≥60 mL/min) renal impairment, and 2times per year in patients with CKD stage III (CrCl 30–60 ml/).

The estimation of CrCl using the Cockcroft-Gault formula appear to be the most appropriate method to monitor renal function in patients receiving NOACs. It is important to recognize and treat all conditions that may have impact on renal function. Furthermore, close monitoring for any signs or symptoms of bleeding are of vital importance.

Hepatic impairment

NOACs should be used with caution in patients with hepatic im-pairment. In patients receiving NOACs, hepatic function should al-ways be taken into consideration not only because NOACs undergo some degree of hepatic metabolism but also because liver dysfunc-tion could have impact on coaguladysfunc-tion.

Dabigatran is well tolerated by patients with mild to moderate he-patic impairment [43]. Nonetheless, dabigatran is contraindicated

in hepatic impairment or liver disease anticipated to have impact on survival [44]. The safety of dabigatran has not been evaluated in

patients with active liver disease, and the use of dabigatran is not recommended if hepatic enzymes exceed three times the upper limit of normal (ULN)]. Although the principal route of rivaroxaban elimination is renal excretion, hepatic clearance plays an important role, with a significant increase in rivaroxaban exposure in patients with moderate hepatic impairment [45]. Thus, the use of rivaroxaban should be avoided in patients with moderate-to-severe hepatic im-pairment or in patients with any hepatic disease associated with co-agulopathy and clinically significant risk of bleeding complications

[46]. Apixaban should be used cautiously in patients with hepatic

impairment, but due to lack of clinical experience with the use of apixaban in patients with moderate hepatic impairment no dose recommendation is provided in this patient population. However, apixaban is contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic impair-ment or in those with hepatic disease associated with coagulopa-thy and clinically significant bleeding risk [47].

Gastrointestinal bleeding

In the RE-LY trial, GI bleeding was significantly more common with dabigatran 150 mg. The higher rate of GI bleeding with dabiga-tran could be explained in the context of low bioavailability, which results in high concentrations of active drug during transit of the gastrointestinal tract [48].

In ROCKET-AF study, rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily showed a signifi-cantly lower incidence of intracranial bleeding but a signifisignifi-cantly higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeds compared to warfarin. In the ARISTOTLE study the incidence of GI bleeds was lower with apixa-ban compared to warfarin. In view of these data, careful benefit/ risk assessment is of crucial importance prior to prescribing NOACs for patients who are at high-risk for GI bleeding

The elderly, patients with a history of GI bleeding or patients with gastrointestinal tract pathology, such as diverticulosis and angio-dysplasia, inflammatory bowel disease could be at increased of GI bleeding. It would also be reasonable to consider the use of a proton pump inhibitor to add gastroprotection reducing the risk of GI bleeds. In a recent study that evaluated the efficacy and safety of dabigatran in an ‘everyday clinical practice’ population revealed that although there was no difference in major bleeding risk between dabigatran (both doses) and warfarin, gastrointestinal bleeding was lower with dabigatran 110mg (aHR: 0.60, 95%CI: 0.37-0.93) compared to warfarin [49].

Monitoring anticoagulation effect

One of the major advantages of NOACs is that there is no need for routine coagulation monitoring. In certain clinical situations such as bleeding complications or in case of surgical emergencies the assessment of the anticoagulant status of the patients receiving NOACs may be useful. Currently there are no routinely available specific coagulation tests for this. The INR is not appropriate for the qualitative assessment of NOACs and should therefore not be used in this context.

The Ecarin clotting time (ECT) and thrombin clotting time (TCT, He-moclot) are considered sensitive tests in order to assess the pres-ence [50] of anticoagulation effects attributed to dabigatran. If the

TT or ECT is normal, it is reasonable to assume that plasma concen-trations of dabigatran are minimal. Nonetheless, these coagulation tests are not specific for dose adjustments of the NOACs.

Although there is correlation between dabigatran plasma concen-trations and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) results, the correlation is nonlinear. However, the aPTT can be used as a qualitative indicator of anticoagulation effect (not intensity), attrib-uted to dabigatran. This is useful in the setting of active bleeding or surgical emergencies. Indeed in this context a normal aPTT result will imply a lack of residual anticoagulant effect.

Prothrombin time (PT) is expected to be prolonged in patients re-ceiving rivaroxaban but it is not reliable for measuring the antico-agulant effects of rivaroxaban. Despite the fact that the use of apix-aban is associated with prolongation of PT, INR and aPTT, the use of these coagulation tests is not recommended in order to obtain quantitative assessments of the anticoagulant effects of apixaban. Of note, the anti-Xa assay represent provide a more reliable quanti-tative assessment of the anticoagulant effect for the oral Factor Xa inhibitors [51,52].

The anti-Factor Xa assays have been developed for the quantita-tive determination of rivaroxaban and apixaban using standardized anti-Factor Xa method and validated calibrators and controls[53]. The Xa assay is sensitive to lower amounts of rivaroxaban and apixaban with less variability and may help assess the direct effects of these agents. Chromogenic -based anti-Xa assays are currently considered reasonably sensitive screening tests for the presence of rivaroxaban and apixaban [54,55].

Table 5: Time for restoration of hemostasis after the last dose of NOACs[57].

HALF LIFE ESTIMATE NORMALIZATION OF HAEMOSTASIS

DABIGATRAN 14-17 hours If normal renal function: 12–24 h If CrCl: 50–80 mL/min: 24–36 h

IfCrCl:30–50 mL/min: 36–48 h If CrCl <30 mL/min: ≥48 h

RIVAROXABAN 5-13h Normalization of haemostasis: 12–24 hours

APIXABAN 9-14h Normalization of haemostasis: 12–24 hours

Antidote and management of bleeding

One limitation of the novel anticoagulants is the lack of well estab-lished specific antidote in order to reverse of their anticoagulants effects. Thus the management of the hemorrhagic events is based primarily in supportive strategies rather than in antidotes or spe-cific procedures of reversal of their anticoagulants effects.

In view of the relative short half-life of NOACs compared to war-farin, cessation of treatment may be sufficient to reverse the anti-coagulant effect in case of less serious bleeding (Table 5). Indeed, restoration of haemostasis is to be expected within 12–24 h after the last taken dose of NOACs. [56]

Thus, determining the dosing regimen and the timing of the last administration of NOACs could provide guidance in the context of non life threatening hemorrhage. In contrast to warfarin, none of the NOACs has currently specific compounds currently that directly counteract the anticoagulation effects of NOACs.

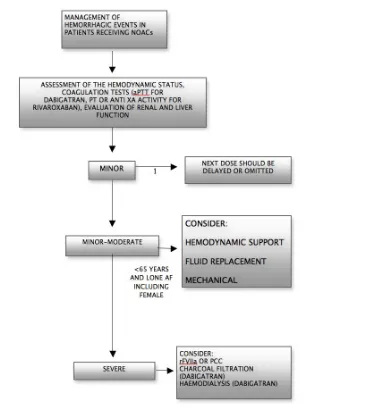

The approach of hemorrhagic complications should be driven mainly by clinical judgment. Indeed management should be con-sidered on individual basis according to the severity of the bleed-ing events. The management of bleedbleed-ing complications accordbleed-ing ESC guidelines 2012 is depicted in Figure 2.

Appropriate symptomatic treatment, with mechanical compres-sion fluid replacement and haemodynamic support, blood prod-uct are of crucial importance. Where a recent overdose of NOACs is suspected, the use of activated charcoal, reduces absorption of NOACs, thereby may be helpful in the control of the bleeding com-plications. Moreover, dabigatran can be removed by dialysis if rapid reversal of its anticoagulant effects is required[50]. On the other hand, due to the high plasma protein binding, rivaroxaban and apixaban cannot be removed by dialysis [58].

Given that renal excretion of NOACs represents an important route of elimination it is crucial to ensure an adequate level of diuresis. Although, procoagulant reversal agents such as prothrombin com-plex concentrate (PCC), has not been evaluated in clinical studies, in case of life threatening hemorrhage their uses should be con-sidered.

Although the role of three-factor prothrombin complex concen-trates (PCCs) in this field still remain unestablished there is some experimental evidence to support the role of four factor PCCs in reversing the anticoagulant effects of NOACs[59-64,58]. There is no

strong evidence as to whether the activated PCC is superior to PCC in the management of life threatening bleeding in patients receiv-ing NOACs. Further research is also required in order to elucidate the role of recombinant-activated factor VIIa (rFVIIa) in the manage-ment of bleeding complications in patients receiving NOACs[65].

Nevertheless, the use of rFVIIa in patient with life-threatening bleeding may be warranted [28].

Fresh-frozen plasma (FFP) does not reverse the anticoagulant effect of NOACs thus its use as a reversal agent is not expected to be use-ful. However, FFP could be useful as plasma expander during acute bleeding [57].

332 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICINE VOL III ISSUE I Perioperative management

Given the absence of well established methods to reverse pro-longed bleeding times, particular caution is needed in patients taking NOACs. Perioperative management should be established on individual basis taking in considerations the individual throm-botic–bleeding risk and the type of surgery planned.

In case of patients who undergo procedures with minimal hemor-rhagic risk such as cataract, glaucoma or dental procedures, the in-tervention can be planned 18–24 h after the last administration of the anticoagulant[57]. In patients who have standard risk of

bleed-ing it is reasonable to interrupt NOACs for 24 hours prior to elective surgical procedures provided that patients have normal renal func-tion [57]. In case of patients with normal renal function undergoing procedures that carry a high risk of major hemorrhagic complica-tions, it is recommended to stop NOACs 2 days in advance.

Figure 2: Management of bleeding complications in patients recieving NOACs

If the risk of bleeding is high, normal aPTT or PT result in the setting of dabigatran or rivaroxaban, respectively, would suggest a lack of residual anticoagulant effect [55, 50]. A formal management based

on normalization of the aPTT or PT prior to surgical procedures has not been established

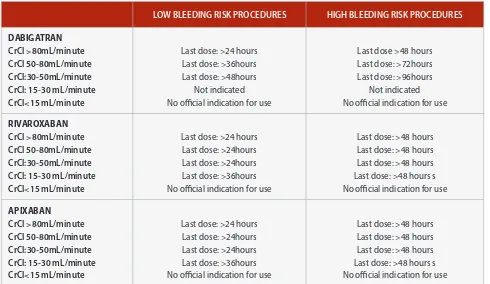

Table 6: A Suggested perioperative management approach.

In patients who are receiving rivaroxaban or apixaban, preopera-tive drug discontinuation is related to the drug elimination half-life, the renal function and the drug dependence on renal excretion (33% for rivaroxaban, 25% for apixaban). As illustrated in Table 6, rivaroxaban and apixaban should be interrupted at least 24hours before low bleeding risk intervention.

In patients with severe renal impairment (CrCl: 15-30ml/minute) the period of discontinuation of both rivaroxaban and apixaban should be longer (at least 36h).

A preoperative management strategy is described in Table 6 [57].

LOW BLEEDING RISK PROCEDURES HIGH BLEEDING RISK PROCEDURES

DABIGATRAN CrCl >80mL/minute CrCl 50‐80mL/minute CrCl:30-50mL/minute CrCl: 15-30 mL/minute CrCl<15 mL/minute

Last dose: >24 hours Last dose: >36hours Last dose: >48hours

Not indicated No official indication for use

Last dose >48 hours Last dose: >72hours Last dose: >96hours

Not indicated No official indication for use

RIVAROXABAN CrCl >80mL/minute CrCl 50‐80mL/minute CrCl:30-50mL/minute CrCl: 15-30 mL/minute CrCl<15 mL/minute

Last dose: >24 hours Last dose: >24hours Last dose: >24hours Last dose: >36hours No official indication for use

Last dose: >48 hours Last dose: >48 hours Last dose: >48 hours Last dose: >48 hours s No official indication for use

APIXABAN CrCl >80mL/minute CrCl 50‐80mL/minute CrCl:30-50mL/minute CrCl: 15-30 mL/minute CrCl<15 mL/minute

Last dose: >24 hours Last dose: >24hours Last dose: >24hours Last dose: >36hours No official indication for use

Last dose: >48 hours Last dose: >48 hours Last dose: >48 hours Last dose: >48 hours s No official indication for use

Given that the risk for major bleeding complications after some types of surgery may outweigh the risk for thromboembolism, cau-tion may be required [68]. Thus, NOACs should be restarted

post-operatively when adequate hemostasis has been achieved. NOACs should be restarted 6–8 h after the procedure if immediate and adequate hemostasis has been achieved and the clinical situation allows [57]. On the other hand in high bleeding risk surgical inter-ventions full dose anticoagulation should be deferred 48–72 h af-ter the invasive procedure. Prophylactic doses of LMWH 6-8 hours after the procedure should be considered before resuming NOACs in immobilized patients at high thrombo-embolic risk if adequate hemostasis has been established [57].

Patients who present with an acute coronary syndrome

Patients receiving NOACs may also present withacute coronary syn-drome (ACS). Treating AF patients presenting with an ACS repre-sent a challenging task in clinical practice. Taking into consideration not only that the DAPT does not eliminate completely the risk of late stent thrombosis (the rate is about 0.6% per year in patients on DAPT) but also the limitations of VKAs per se to protect patients from stent thrombosis, management of AF patients after stent im-plantation is complicated [69].

Management should be decided on an individual basis, taking into consideration that the individual bleeding risk should be balanced with the individual ischemic risk. Despite the fact that triple therapy (TT) increases significantly the risk of hemorrhagic complications, this represents the most efficient antithrombotic strategy to pro-tect against both stent thrombosis and thromboembolic complica-tions in AF patients undergoing PCI [70].

334 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICINE VOL III ISSUE I In ATLAS ACS 2–TIMI 51 study, low dose rivaroxaban (2.5mg bid)

reduced the risk of the composite end point of death from car-diovascular causes, myocardial infarction, or stroke at the cost of increased major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage compared to DAPT. Nevertheless there is lack of evidence on ACS in regard to the dose of rivaroxaban used for anticoagulation in AF patients per se, using the stroke prevention dose and treatment regime. In the APPRAISE-2 study, patients were assigned to receive apixaban, in the stroke prevention dose (5 mg b.i.d.), or placebo, in addition to mono or dual antiplatelet therapy. This study showed that the use of apixaban on top of DAPT was associated with higher rate of major bleeding events without a significant reduction in recurrent ischemic events.

Patients who present with an ischaemic stroke

Patients receiving NOACs may also present with an acute ischaemic stroke. In these clinical circumstances it is of crucial importance to estimate the impact of NOACs on the coagulation system and rule out the presence of residual anticoagulant effects before admin-istrating thrombolysis. Thus, thrombolysis should not be adminis-tered regardless of level of prothrombin time, INR, or PTT. Indeed if the aPTT or the PT is prolonged in a patient taking dabigatran or rivaroxaban respectively, as fibrinolytic therapy is potentially of greater risk and thus should not be undertaken [73].

In the RE-LY study, dabigatran 150 mg b.i.d. resulted in a signifi-cant reduction in both ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke, whilst neither rivaroxaban nor apixaban significantly reduced ischaemic stroke, compared with warfarin in the ROCKET-AF and ARISTOTLE trials, respectively.

The timing of initiation of NOACs after stroke has not been estab-lished. The concerns about the use of NOACs in the setting of a new ischaemic stroke are based on the potential risk of causing hemor-rhagic transformation of a new ischemic stroke. In the RE-LY study, patients with a new ischaemic stroke had to wait 2 weeks before initiation of dabigatran. In the ROCKET AF and ARISTOTLE trials, patients could not be treated with rivaroxaban and apixaban within 14 days and 7 days respectively of a new ischemic stroke. In these studies, there was no evidence of increased hemorrhagic transfor-mation with NOACs.

Changing NOACs to (or from) VKAs

It is recommended that dabigatran should be started immediately as soon as the INR falls below 2.0 [74,75]. In the case of transition to

rivaroxaban it is recommended that warfarin should be discontin-ued and rivaroxaban initiate when INR falls to <3.0 (US labeling) or ≤2.5 (Canadian label) [76,77]. In case of conversion from warfarin to apixaban it is recommended starting apixaban when INR <2 [47,78].

When changing from dabigatran to warfarin, the precise time that warfarin should be started depends on renal function. In particular it is recommended that warfarin should be started 3 days before discontinuing dabigatran in case CrCl is more than 50 mL/min and 2days when CrCl falls between 30 to 50 mL/min [44]. In regard to

the conversion from rivaroxaban to warfarin it is suggested that pa-tients should be treated with warfarin and a parenteral anticoagu-lant 24 hours after discontinuation of rivaroxaban (US prescribing information) [76]. Rivaroxaban should be administrated

concomi-tantly with warfarin until INR ≥2.0 [77].

For apixaban, this should be interrupted and start both a parenteral anticoagulant and warfarin at the time the next dose of apixaban would have been taken. Parenteral anticoagulant should be dis-continued when INR reaches the target range [78]. According to

Ca-nadian labeling warfarin should be administrated at usual starting doses and continue apixaban until INR ≥2. Then apixaban should be interrupted [47].

Cardioversion and ablation

According ESC guidelines in patient with AF of >48 h duration or when there is doubt about its duration, oral anticoagulant is rec-ommended at least 3 weeks prior to cardioversion. Alternatively, early cardioversion may be performed after exclusion of left atrial thrombi by transesophageal echocardiography.

Based on the 2012 ESC guidelines focused update dabigatran rep-resent a valid alternative to warfarin in patients undergoing elec-tive cardioversion. Although there is a lack of prospecelec-tive regis-tries, observational data from the RE-LY, ROCKET-AF and ARISTOTLE trials did not reveal any difference in the rate of strokes or systemic thromboembolic events [79-81].

Thus, cardioversion could be considered safe in patients receiving NOACs provided that effective anticoagulation could be reliably confirmed. In case of uncertainty in regard to the adherence to the anticoagulant therapy it is considered appropriate to rule out the presence of left atrial thrombi performing TEE.

What about AF ablation? One study revealed that ablation carried out whilst still taking dabigatran is associated with increased risk of bleeding or thromboembolic complications compared with unin-terrupted warfarin therapy [82]. On the other hand, another study

using a protocol based strategy in the periablation setting found that dabigatran has a favorable efficacy and safety profile [83]. An-other recent study that evaluated outcomes in patients with AF treated with warfarin or rivaroxaban undergoing cardioversion or catheter ablation found that rivaroxaban was a safe alternative to warfarin peri-cardioversion or ablation [81].

CONCLUSION

The limitations and concerns associated to warfarin led to the development of novel anticoagulant agents with favorable phar-macologic properties which aim at increasing of the percentage of AF patients under effective and safe anticoagulant therapy. De-spite the fact that VKAs still represent the only therapeutic option in patients with mechanical prosthetic valves and end stage renal impairment, NOACs constitute a landmark shift in the field of anti-coagulant treatment.

REFERENCES

Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001 May 9;285(18):2370-5.

Olesen JB, Lip GYH, Kamper A-L, Hommel K, Kober L, Lane DA, Lindhardsen J, Gislason GH, Torp-Pedersen C. Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2012;367:625–635.

Hohnloser SH, Hijazi Z, Thomas L, Alexander JH, Amerena J, Hanna M, Keltai M, Lanas F, Lopes RD, Lopez-Sendon J, Granger CB, Wallentin L. Efficacy of apixaban when compared with warfarin in relation to renal function in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2821–2830

Stangier J, Stähle H, Rathgen K, Roth W, Shakeri-Nejad K.

Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dabigatran etexilate, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor, are not affected by moderate hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48:1411–1419

Pradaxa, European Summary of Product Characteristics, 2011

Kubitza D, Roth A, Becka M, Alatrach A, Halabi A, Hinrichsen H, Mueck W. Effect of hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics and

pharmacodynamics of a single dose of rivaroxaban - an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013 Jan 8

Xarelto Summary of Product Characteristics – EU. http://www.xarelto.com

Product monograph for Eliquis. Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada. Montreal, QC H4S 0A4. November 2012.

Eikelboom JW, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz M, Healey JS, Oldgren J, Yang S, Alings M, Kaatz S, Hohnloser SH, Diener HC, Franzosi MG, Huber K, Reilly P, Varrone J, Yusuf S. Risk of bleeding with 2 doses of dabigatran compared with warfarin in older and younger patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy (RE-LY) trial.

Circulation. 2011 May 31;123(21):2363-72.

Larsen TB, Rasmussen LH, Skjøth F, Due KM, Callréus T, Rosenzweig M, Lip GY. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran etexilate and warfarin in ‘real world’ patients with atrial fibrillation: A prospective nationwide cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Apr2

van Ryn J, Stangier J, Haertter S, Liesenfeld KH, Wienen W, Feuring M, Clemens A. Dabigatran etexilate—a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor: interpretation of coagulation assays and reversal of anticoagulant activity. Thromb Haemost 2010;103:1116–1127.

Tripodi A. Measuring the anticoagulant effect of direct factor Xa inhibitors. Is the anti-Xa assay preferable to the prothrombin time test? ThrombHaemost2011; 105:735–736.

Barrett YC, Wang Z, Frost C, Shenker A. Clinical laboratory measurement of direct factor Xa inhibitors: anti-Xa assay is preferable to prothrombin time assay. ThrombHaemost2010;104:1263–1271.

Samama MM, Contant G, Spiro TE, Perzborn E, Guinet C, Gourmelin Y, Le Flem L, Rohde G, Martinoli JL; Rivaroxaban Anti-Factor Xa

Chromogenic Assay Field Trial Laboratories. Evaluation of the anti-factor Xa chromogenic assay for the measurement of rivaroxaban plasma concentrations using calibrators and controls. Thromb Haemost. 2012 Feb;107(2):379-87

Eby C. Novel anticoagulants and laboratory testing. Int J Lab Hematol. 2013 Jun;35(3):262-8

Samama MM, Guinet C. Laboratory assessment of new anticoagulants. Clin Chem Lab Med 2011;49:761–72.

Levi M, Eerenberg E, Kamphuisen PW. Bleeding risk and reversal strategies for old and new anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents. J Thromb Haemos 2011;9:1705–12.

Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M, Antz M, Hacke W, Oldgren J, Sinnaeve P, Camm J, Kirchhof P. EHRA practical guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Eur Heart J (2013). 58. Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, Meijers JC, Buller HR and Levi M. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011; 124: 1573-9.

Zhou W, Schwarting S, Illanes S et al. Hemostatic therapy in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage associated with the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran. Stroke. 2011; 42:3594-9.

Dager WE. Developing a management plan for oral anticoagulant reversal. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. In press

Kalus JS. Pharmacologic interventions for reversing the effects of oral anticoagulants. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. In press.

Marlu R, Hodaj E, Paris A et al. Effect of non-specific reversal agents on anticoagulant activity of dabigatran and rivaroxaban: a randomised crossover ex vivo study in healthy volunteers. Thromb Haemost. 2012; 108:217-24.

Siegal DM, Cuker A. Reversal of novel oral anticoagulants in patients with major bleeding. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013 Feb 7. [Epub ahead of print]

Levy JH, Faraoni D, Spring JL, Douketis JD, Samama CM.

Managing new oral anticoagulants in the perioperative and intensive care unit setting. Anesthesiology. 2013 Feb 14. [Epub ahead of print]

Warkentin TE, Margetts P, Connolly SJ, Lamy A, Ricci C, Eikelboom JW. Recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) and hemodialysis to manage massive dabigatran-associated post-cardiac surgery bleeding. Blood 2012;119:2172–2174

Lu G, Deguzman FR, Hollenbach SJ, Karbarz MJ, Abe K, Lee G, Luan P, Hutchaleelaha A, Inagaki M, Conley PB, Phillips DR, Sinha U.A specific antidote for reversal of anticoagulation by direct and indirect inhibitors of coagulation factor Xa. Nat Med. 2013 Apr;19(4):446-51. doi: 10.1038/ nm.3102. Epub 2013 Mar 3.

336 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOVASCULAR MEDICINE VOL III ISSUE I

Product information for Pradaxa. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Ridgefield, CT 06877. December 2012.

Product monograph for Pradaxa. Boehringer Ingelheim Canada Ltd. Burlington, ON L7L 5H4. December 2012.

Product information for Xarelto. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Titusville, NJ 08560. November 2012.

Product monograph for Xarelto. Bayer Inc. Toronto, ON M9W 1G6. July 2012.

Product information for Eliquis. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Princeton, NJ 08543. December 2012.

Nagarakanti R, Ezekowitz MD, Oldgren J, Yang S, Chernick M, Aikens TH, Flaker G, Brugada J, Kamensky G, Parekh A, Reilly PA, Yusuf S, Connolly SJ. Dabigatran vs. warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of patients undergoing cardioversion. Circulation 2011;123:131–136.

Flaker G, Lopes R, Al-Khatib S, Hermosillo A, Thomas L, Zhu J, Ruzyllo W, Mohan P, Granger C. Apixaban and warfarin are associated with a low risk of stroke following cardioversion for AF: results from the ARISTOTLE Trial. Eur Heart J 2012;33(Abstract Supplement):686.

Piccini JP, Stevens SR, Lokhnygina Y, Patel MR, Halperin JL, Singer DE, Hankey GJ, Hacke W, Becker RC, Nessel CC, Mahaffey KW, Fox KA, Califf RM, Breithardt G; ROCKET AF Steering Committee & Investigators. Outcomes Following Cardioversion and Atrial Fibrillation Ablation in Patients Treated with Rivaroxaban and Warfarin in the ROCKET AF Trial.

Lakkireddy D, Reddy YM, Di Biase L, Vanga SR, Santangeli P, Swarup V, Pimentel R, Mansour MC, D’Avila A, Sanchez JE, Burkhardt JD, Chalhoub F, Mohanty P, Coffey J, Shaik N, Monir G, Reddy VY, Ruskin J, Natale A. Feasibility and safety of dabigatran versus warfarin for periprocedural anticoagulation in patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: results from a multicenter prospective registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012 Mar 27;59(13):1168-74

Winkle RA, Mead RH, Engel G, Kong MH, Patrawala RA. The use of dabigatran immediately after atrial fibrillation ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012; 23(3):264-8.

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

REFERENCES (Continued)

Hutchaleelaha A, Lu G, Deguzman FR, Karbarz MJ, Inagaki M, Yau S, Conley PB, Sinha U. Hollenbach S.J. Recombinant factor Xa inhibitor antidote (PRT064445) mediates reversal of anticoagulation through reduction of free drug concentration: a common mechanism for direct factor Xa inhibitors. ESC Congress 2012. Citation European Heart Journal ( 2012 ) 33 ( Abstract Supplement ), 496

Spyropoulos AC, Turpie AG. Perioperative bridging interruption with heparin for the patient receiving long-term anticoagulation. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2005;11(5):373-379.

Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, Abrecht L, Vaina S, Morger C, Kukreja N, Jüni P, Sianos G, Hellige G, van Domburg RT, Hess OM, Boersma E, Meier B, Windecker S, Serruys PW. Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007 ;369(9562):667-78.

Menozzi M, Rubboli A, Manari A, De Palma R, Grilli R. Triple antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing coronary artery stenting: hovering among bleeding risk, thromboembolic events, and stent thrombosis Thromb J. 2012 ;10(1):22.

Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Bassand JP, Bhatt DL, Bode C, Burton P, Cohen M, Cook-Bruns N, Fox KA, Goto S, Murphy SA, Plotnikov AN, Schneider D, Sun X, Verheugt FW, Gibson CM; ATLASACS 2–TIMI 51 Investigators. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recentacute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2012, 366:9-19.

Alexander JH, Lopes RD, James S, Kilaru R, He Y, Mohan P, Bhatt DL, Goodman S, Verheugt FW, Flather M, Huber K, Liaw D, Husted SE, Lopez-Sendon J, De Caterina R, Jansky P, Darius H, Vinereanu D, Cornel JH, Cools F, Atar D, Leiva-Pons JL, Keltai M, Ogawa H, Pais P, Parkhomenko A, Ruzyllo W, Diaz R, White H, Ruda M, Geraldes M, Lawrence J, Harrington RA, Wallentin L; APPRAISE-2 Investigators. Apixaban with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome.

N Engl J Med2011, 365:699-708.

Matute MC, Masjuan J, Egido JA, Fuentes B, Simal P,

Dı´az-Otero F, Reig G, Dı´ez-Tejedor E, Gil-Nun˜ez A, Vivancos J, Alonso de Lecin˜ana M. Safety and outcomes following thrombolytic treatment in stroke patients who had received prior treatment with anticoagulants. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;33:231–239.

67

68

69

70

71

72

![Table 5: Time for restoration of hemostasis after the last dose of NOACs[57].](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/3964293.1907713/4.595.58.539.112.247/table-time-restoration-hemostasis-dose-noacs.webp)