UNDERSTANDING THE MACROECONOMIC

BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT Of EAST AND

SOUTHEAST ASIA

A Reader

Definitions of terms

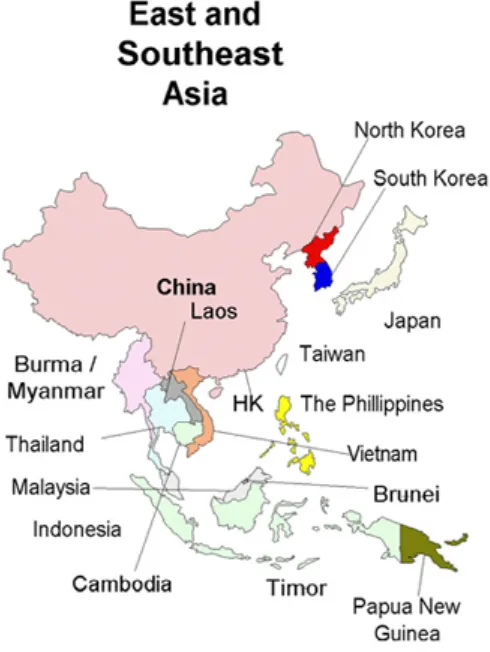

East and Southeast Asia comprises the region roughly situated south of Russian Siberia and East of India. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Map of East and Southeast Asia

Note that the terminology is not always clear. Sometimes the whole region is referred to as “East Asia” – especially in economic contexts. Sometimes China + Korea + Japan are called “Northeast Asia”, sometimes “East Asia”. Moreover the following labels are often used:

• “Far East”, meaning roughly the same as “East and Southeast Asia”

• “Asia-Pacific”: East and Southeast Asia + Australia and Pacific island states

In this reader, we use “Asia” for short when referring to East and Southeast Asia.

ASEAN is the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the most important vehicle for co-operation and integration in Asia. All Southeast Asia countries are members. ASEAN + 3: A loose co-operation structure between ASEAN and China, Korea and Japan; aims at establishing a free trade area (and maybe more) in the long term. NICs or NIEs: Newly Industrialised Countries (Economies); refers traditionally to Hong Kong, Korea, Singapore and Taiwan (but de facto todayseveral other countries could also be included).

The importance of Asia in the world economy

Asia as a whole (including India etc.) accounted for 60 percent of the global production as late as 1820. The share reached its lowest level after World War II with 18.5 percent in 1950 and was 37 percent in 1998 (Bigsten 2002). East and Southeast Asia accounted for 31 percent of the world’s population and 00 percent of its exports in 2000. Foreign Direct Investment1 inflows to Asia (excluding Japan) has been dominating among “developing countries” 2 and comprised 60 percent in 2002. See

Table 1.

Table 1. FDI inflows to Asia, USD billion

2001 2002

Source: United Nations (2003): World Investment Report. N.Y. and Geneva.

East and Southeast Asia, excluding Japan, absorbed 21 percent of global inward FDI on average 1991-96. (Japan took only 0.3%.). In 2002, East and Southeast Asia received 13 percent, excluding Japan, while Japan received 1.4%. As to outward

excluding Japan, while Japan alone accounted for 7.5 percent. Note that the figures may differ rather drastically from year to year.

The direction of the FDI flows has changed over the years: In the 1980s and 1990s, Southeast Asia was the major recipient, while recently (after the Asian crisis 1997-98) China has become the leading recipient. Note that inwards FDI to Japan was very small until recently. However, during the last few years Japan has received increasing volumes of FDI, partly as a result of deliberate policy.

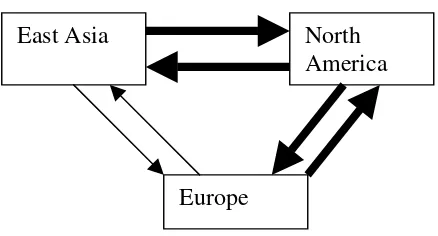

In the global economy, Asia interacts mainly with North America and Europe (the so-called triad), while the rest of the world is more or less marginalised. Note also that the economic relations between Asia and North America are much closer and more developed than those between Asia and Europe. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. The triad

North America

Europe East Asia

Some basic economic facts

A characteristic trait for the region is its heterogeneity:

• N.B. the size of the Japanese economy: Japan alone accounts for 65 percent of the region’s production (but only 29 percent of its exports). Note that these figures used to be much higher. China’s share of production is about 15 percent and its share of exports is 15 percent, too.

• Some of the world’s richest countries and territories are in Asia (Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore) but also some of the poorest (Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia).

(China, Indonesia, Philippines), some are very capital-abundant (e.g. Singapore), etc.

• Economic and political systems are very diverse. Some (like China, Vietnam and Laos) are still one-party (nominally) socialist economies, some very liberal market economies (such as Hong Kong).

• Some are very large (China) and some very small (Singapore, Brunei).

Diversity seems to provide scope for a beneficial division of labour in the region. The Asian development has been development of interdependent economies. Much of the trade and FDI flows are intra-regional. This reduces the dependence of the region on trade cycles in other parts of the world. On the other hand, trouble in one major economy spreads easily to the rest of the region, as shown by the Asian crisis in the late 1990s.

There are also common traits, however, with occasional exceptions:

• High growth rates on average over the long term

• High rates of savings and investment

• Emphasis on education and health care

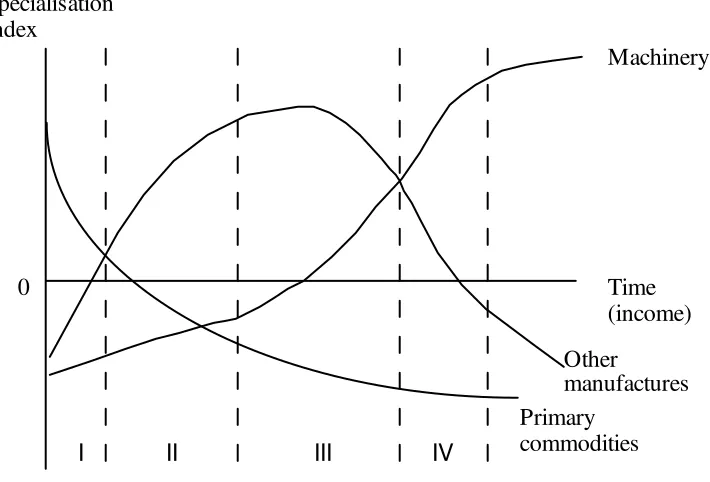

Structural change

Economic development is regular accompanied by a restructuring of the economy. The share of the primary sector (agriculture etc.) decreases while that of industry increases. Finally, the service sector tends to take over as the dominant sector. For Asia, see Table 3.

Income distribution

Table 3. Sectoraldistribution of GDP, %

Country Agriculture Industry Services

1970 2001 1970 2001 1970 2001

China 42 11 45 66 13 24

Indonesia 35 16 28 36 37 48

Philippines 28 20 34 34 38 46

Thailand 30 8 26 44 44 48 Malaysia n.a. 23 n.a. 43 n.a. 49

Korea 30 5 24 44 46 51

Hong Kong n.a. 0 n.a. 14 n.. 86

Singapore 2 0 36 31 61 69

Japan n.a. 2 n.a. 37 n.a. 61

Source: Dowling & Valenzuela, World Bank.

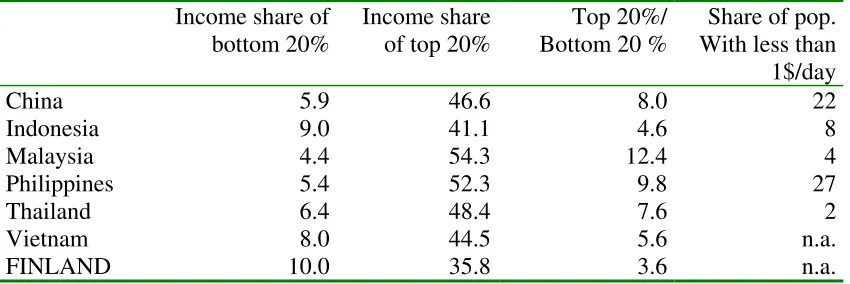

Table 4. Income distribution, 2000

Income share of bottom 20%

Income share of top 20%

Top 20%/ Bottom 20 %

Share of pop. With less than

1$/day

China 5.9 46.6 8.0 22

Indonesia 9.0 41.1 4.6 8

Malaysia 4.4 54.3 12.4 4

Philippines 5.4 52.3 9.8 27

Thailand 6.4 48.4 7.6 2

Vietnam 8.0 44.5 5.6 n.a.

FINLAND 10.0 35.8 3.6 n.a.

Source: Kokko 2003.

Health status

Health is another indicator of development; see Table 3. Health status is closely, but not perfectly, correlated with national income per capita.

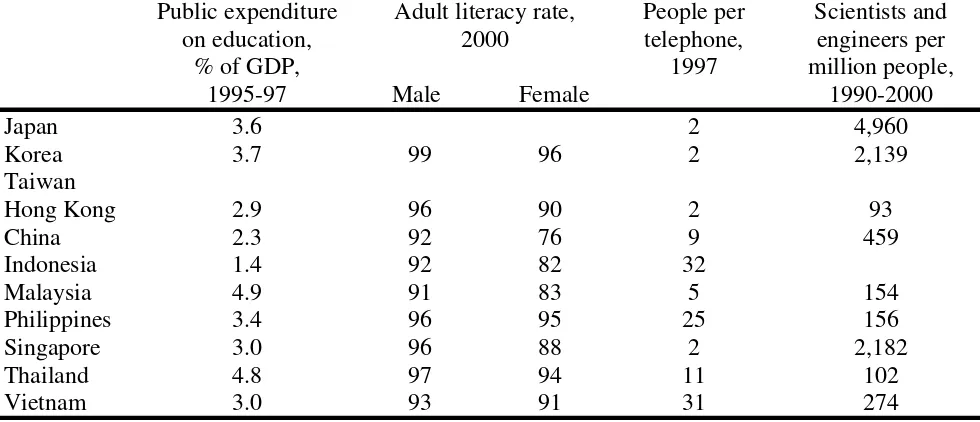

Education and technology

Table 3. Helth indicators

Table 4. Some indicators of the level of education and technology

Explaining economic development in Asia

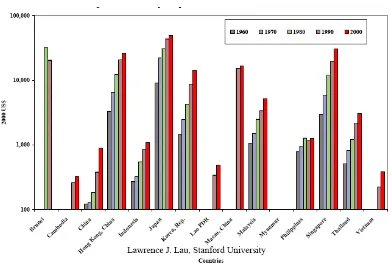

With some notable exceptions, East and Southeast Asia is the most successful example of economic development during the last four decades. See Figure 3, to get an idea of the growth of the GDP/capita3 in the region.

Figure 3. Real GDP per capita in Asia, 1960 – 2000 at 1995 prices

Source: Lau 2003.

Given the favourable development, researchers have been looking for an “Asian development model”, i.e., is there a common set of policy measures that can explain what happened? A typical formulation is the following one (El Kahal 2001):

“The Asian Model”

• A stable macroeconomic and financial system - limited fiscal deficits

- encouraged savings

- encouraged investment, including FDI - avoided overvalued exchange rates

• State interventionism

- selective interventions (industrial policy): targeting credit to selected industries, artificially low borrowing rates, protecting import substitutes, public investment in applied research, etc.

- export promotion

- performance-based credit allocation (cheap funding required meeting certain performance targets)

• Administrative competence - public spending on education

- governments guided but did not override the decisions of firms

policies were constantly subject to review, ineffective policies were quickly abandoned

- qualified government bureaucracy

• Political and economic stability and social cohesion

- government adapted the principle of wealth-sharing (all groups should benefit from growth)

- strong bureaucracy, insulated from political pressure; formalised negotiations between public and private sector to avoid lobbying

- Confucian values and work ethic have been invoked as a reason for success

Note, however, that the above “model” is very oversimplified, as the various points apply to a very different extent in different countries. Hence the talk about an “Asian model” is strongly exaggerated. This is now widely recognised. Instead, the discussion has largely evolved about the question of whether a market-friendly environment or selective government interventionism has been the decisive factor behind the development, or whether there may be other important reasons as well. Moreover, there are also examples of less successful development in the regio. Even those cases should be possible to explain!

The main competing arguments are:

advantages. This, in combination with favourable external conditions, such as strongly expanding global trade in the late 1900s, fuelled economic growth. 2) Government intervention was crucial for “guiding” the development. The

government provided, often within an authoritarian framework,

• promotion of selected industries (“picking winners”)

• investment in education, health care, housing etc.

• basic institutions (law and order, property rights etc.)

• prudent macroeconomic management (keeping inflation and unemployment in check, balanced government finances etc.)

• protection against self-serving special interests 3) Other factors

• Culture (Asian cultural tradition may be conducive to development)

• Geographical factors (good possibilities for optimal division of labour, according to comparative advantages; cf. the “Flying geese” model below.

• Note that these factors must be seen as complementary to the first two categories.

Problems

It is easy to see that all the above explanations are “wrong” in the sense that they all can be easily criticised:

• It is misleading to think that markets have been left alone, although they were often less distorted than in most other developing countries. Most government have, in fact, intervened more or less heavily in the markets.

• Government regulations are not unusual in developing countries, but the result has often been poor. One reason is the danger for interventions to cause distortions and promote inefficiency. Another reason is that authoritarian governments may easily turn predatory. See article in Appendix 1.

It seems clear that most countries have applied a mix of market-led development and government interventions. To see what the market and the government, respectively, can do, we look at the two major trade and industrialisation strategies: Import substitution (IS) and export orientation (EO):

Import substitution model: Produce for a protected home market; substitute domestic goods for imports. To achieve this, trade barriers, subsidies or foreign exchange controls were imposed. This was the strategy applied by most developing countries until the 1980s. Although it has been largely abandoned by now, especially in Asia, there remain traits of that policy in many countries.

The theoretical rationale for the IS model is the so-called infant industry argument

which says thatnew industries are not competitive with established ones in developed countries without protection. In the long run, it is argued, the protected industry will become competitive without protection through “learning by doing.” However, in practice, the results have been mostly discouraging:

• Since the domestic market is small, they are soon saturated and the growth potential is exhausted. Moreover, there is little competition, leading to inefficiency, high costs and low quality;

• It is hard to get beyond the easy phase of IS, production of simple consumption goods; when IS was extended to capital and intermediate goods production the result was often poor products at a high price.

• IS requires regulations: bureaucracy leads to slow decision-making. Decisions on investment and technological innovation at the firm level are delayed.

• Special interests are created, which want protection to go on. Firms may use resources to influence government and secure more protection; this may lead to corruption, and mitigates the incentive to produce efficiently.

Conclusion: IS as a strategy has been unsuccessful. It is difficult to back down, however, because of strong special interests and because extensive restructuring of the industry is often necessary.

In Asia, most countries (exceptions Hong Kong, Singapore, Brunei) adopted IS policies after the war. The IS policies were gradually abandoned, beginning, with the Newly Industrialised Economies (NIEs), Korea and Taiwan in the early 1960s. From the mid 1980s most of Asia had abandoned IS, but selective protection did not disappear altogether.

The export-led model: Produce for the world market according to your comparative advantages, i.e., each country should specialise in products that it is relatively good at producing and import the rest. The country is then engaged in the global division of labour.Several interpretations of the EO concept is possible:

a) Deregulate and let the markets determine what to produce; the govt may step in, however, when the markets do not work properly (e.g., research and development (R&D), education, training of labour, housing and health care);

b) Measures that favour the export sector or particular industries with comparative advantages or potential comparative advantage. (Tax concessions, cheap credits, tariff exemption for inputs, government enterprises for input manufacturing). This alternative means heavy intervention, too. This is what is meant by industrial policy.

How can government intervention be defended in the case of EO, which is, in principle, a market-oriented strategy?

• Firms may be reluctant to take the risk involved in venturing into global markets;

• Capital markets are often rudimentary in developing countries (difficult to borrow for a firm to overcome initial losses, even if the long-run prospects may be good);

• New export-oriented industries may have external effects (effects that extend beyond the industry itself). For instance, technological and/or managerial knowledge can be diffused to other parts of the economy.

c) Encourage FDI. FDI are “package deals”, involving real capital

(machinery and equipment), technology, management and marketing know-how. Host countries hope for linkage effects to domestic firms and

technology transfer is supposed to contribute to further growth.

Criticism of export-led industrialisation

• A pure market solution may produce a lopsided economy (cf. Brunei (which is very dependent on oil and gas), Singapore (which became concentrated in electronics);

• Distortions in favour of exports may be equally damaging as distortions in favour of import-competing goods—“picking winners” is difficult; ex. heavy and chemicals industries in Korea in the late 70s; heavy industries in Malaysia in the 1980s, the aerospace industry in Indonesia in the 1990s etc. Cf. also the collapse of the Korean chaebol (diversified conglomerates), which were largely built with the aid of industrial policy, in the 1990s.

• The “fallacy of composition” argument: What can be done by one cannot be done by all, if all developing countries would go for export-oriented

When are interventions successful?

As a matter of fact, the Asian governments have been interventionist (with few exceptions, such as Hong Kong), although export-oriented. To which extent this is an

explanation of growth is controversial, it is not certain that the countries have been successful because of this interventionism. The question is, whether the countries could have done as well or better without interventions. (In fact, also many

unsuccessful governments are interventionists.) There are some prerequisites for successful interventions, however:

• It is important that interventions do not work against the market forces in the long run. (A country whose main asset is unskilled labour, for example, should not try and develop hi-tech industries.) This view sees the government as helpful if it intervenes when markets do not the do the job properly. Interventions should not be an instrument for promoting the interest of pressure groups. In East Asia authoritarian but developmental governments kept special interests at bay, and they were prepared change policy quickly if necessary;

• A capable and reasonably uncorrupted bureaucracy, insulated from special interest groups, is important;

• The economic and social institutions should be efficient. This means factors like law and order, protection of property and contract rights, a transparent and predictable business environment etc.

These qualities are present to differing extent in different countries in Asia. There is not “perfect” case. (In Southeast Asia generally weaker public service and institutions than in Northeast Asia.)

The role of cultural factors and geographical synergy

Culture

The East Asian culture (particularly Confucian philosophy) is allegedly conducive to development through emphasising:

• Thrift,

• Education,

• That the group is more important than the individual,

• Respect for authority).

This is also the core of the so-called “Asian values”. These values appear most prominently in Northeast Asia, Vietnam and among the ethnic Chinese community in Southeast Asia. The idea of Asian values is a controversial one, for some discussion, see Appendix 3.

Criticism:

• Although there may well be some truth in these ideas, it is hard to prove them as it is difficult or impossible to measure the effect of “culture”

• Confucian philosophy was earlier cited as an obstacle to economic growth.

• Several non-Confucian countries have been successful as well. Note, however, the role of Chinese minority in, e.g., Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand, where this group is important or decisive for the economy.

Geographical synergy

East Asian countries are close to each other but very different as to factor endowments. Some are labour abundant, some skill abundant and some capital abundant, etc. This may encourage a division of labour that benefits the whole group. The closeness may also promote spill over effects from one country to another; a country may benefit from being close to a successful neighbour through trade and investment links.

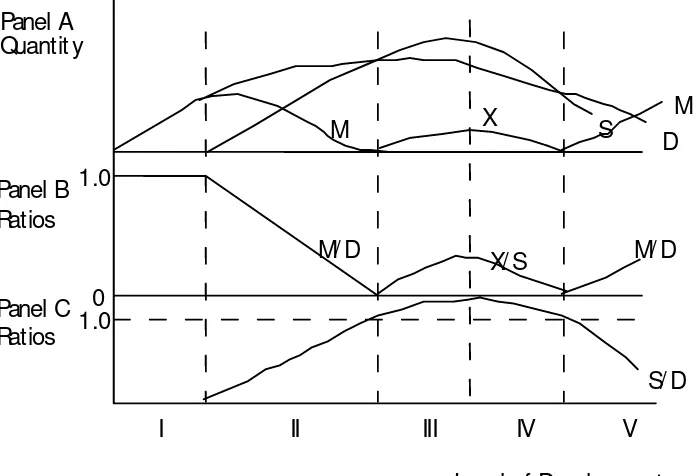

Criticism of the “Flying Geese”:

• Services are difficult to fit into the model: many – although not all – services cannot be removed from their users;

• The pattern has recently become blurred because of the “fragmentation” of production: The final product may be put together from a large number of standard components, manufactured in many different countries and then assembled.

The “overseas” Chinese: More or less informal networks have been built by the activities of ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia who conduct business between

themselves. These networks also play a great role in engaging China in the economic interaction in the region.

Industrial, trade and investment policy

Industrial policy refers to selective interventions by the government in order to change the industrial structure of a country in a way that is perceived as favourable, i.e., more advanced. A broader definition of industrial policy includes attempts at creating a favourable business climate in general. Obviously, this includes trade policy (cf. the discussion on IS and EO policies above) and policy towards FDI. Many Asian countries used, and still use, industrial policy extensively as an instrument for development.

Examples of industrial policy:

Japan

• A new Ministry of Trade and Industry (MITI) was empowered to guide the

industrial development (engaged in industrial planning, financing, enforcing mergers, setting production quotas, rationing foreign exchange, and sourcing and allocating foreign technology to individual firms)

• Rationing of funding and foreign exchange the major instruments, especially

in the beginning; later more indicative “guidance” by the state

• The Ministry of Finance exerted strong influence on the allocation of credits

• Firms were encouraged to aim for export and the infant industry protection

such as subsidised loans, tax holidays treatment, etc were conditional on satisfactory export performance

• FDI not encouraged

• The regulation of competition different from that of the West: Industries were allowed to concentrate, however, competition was fierce despite a small number of players

Korea

• Change took place from IS to EO in the early 1960s

• Export promotion through credit allocation, tax favours, tariff exemptions on inputs; measures mostly targeted very big chaebol

• Incentives linked to export performance

• Simultaneously, protection of home market, also depending on export performance

• Exchange rate policy (the value of the won was kept low)

• FDI not encouraged

• Forced mergers, sales or liquidation because of inefficiency or “excessive

competition”

• Occasional failures happened, especially in the context of the emphasis on heavy industry in the 1970s

Taiwan

• Targeting first labour intense industry; from the mid 1970s heavy industries (with less success) and high-tech industries from the 1980s

• Tax incentives, export credits and insurance etc., but not selective financing

• FDI were encouraged

Southeast Asia

The region took up many traits from export oriented industrial policy in Northeast Asia from the mid 1980s, but the state bureaucracy was usually weaker (except for Singapore) and less insulated from special interest groups and, hence, corruption a bigger problem.

Indonesia

• Export promotion and liberalisation of foreign trade from the mid 1980s but continued targeting of some strategic sectors (capital and/or skill intensive, e.g., aerospace!) with doubtful comparative advantages. Direct state involvement (SOEs) in targeted sectors was also common

• Restrictions on FDI lifted

• Targeting of industries created elite of special interests, which were protected through monopoly rights etc.

• Foreign borrowing was encouraged, which led to a big foreign debt

Malaysia

• Leading theme: Assisting the “indigenous” population i.e., the Malays through SOEs, ownership and employment quotas in private firms (certain percentage had to be Malay), govt procurement, university quotas etc. This was the “New Economic Policy” (NEP), but the similar polices prevail today

• Problems with inefficient SOE and other protected industries and vested special interests, “cronies”

• Less protectionist IS policy to begin with than most LDCs

• FDI encouraged but channelled to special export processing zones (EPZs)

• Recent emphasis on information and communications technology (ICT); a special zone, the Multimedia Supercorridor set up around the capital area

Thailand

• Started out as a major exporter of agricultural goods

often coupled with domestic content requirements. However, investment incentives were applicable to a wide range of industries

• Shift from IS towards EO in the 1980s, especially in labour intensive industries, but domestic industry was still protected by rather high tariffs

• From mid 80s, large inflows of FDI and rapid industrialisation and export growth until the crisis in 1997-98

• Favourable development resumed in the 2000s

China

• Market oriented reforms from 1978 beginning with agriculture

• Increasing role of town-and village enterprises (TVEs) and private firms contributed to strongly increasing exports from the mid 1980s

• Special economic zones and 14 coastal cities were used as vehicles for development and designated sites for FDI. Investment incentives, infrastructure etc. were available at those locations

• From the late 1980s possible to set up FDIs also in other parts of the country

• China tried to target certain industries (textiles, electronics, machinery) but with less than full success

• SOEs “encouraged” to export

• The exchange rate of the renmimbi was kept low in order to preserve and improve international price competitiveness

• China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001; this entails further liberalisation of trade and financial markets

(Kokko 2002)).

Economic co-operation and integration

In Asia there is a high degree of de facto integration (the economies are

interdependent, their economic structure complementary, leading to large intra-regional trade and investment flows). However, there is relatively little organised

integration and co-operation, compared to other parts of the world.

d) the big players (Japan and China) have relied on multilateral arrangements (WTO) instead of regional solutions. Institution building for regional co-operation only slowly got started in the 1960.

In the 1990 the situation has gradually changed, but co-operation and (organised) integration still proceed slowly because of the heterogeneity and large size of the region (note that North America often have to be included because of their importance as trade partners). Several organisations also have a de facto background in security considerations despite being referred to as economic co-operation.

Terminology

Economic co-operation is a more general and looser term than integration. In principle, co-operation can concern everything between a one-off consultation (e.g. taking a common standpoint in international negotiations, building a bridge or railway between neighbouring countries, etc.) to total co-ordination of economic policies. In international organisations, co-operation is usually about production of so-called public goods (goods whose production has a positive or negative side-effect on the society at large). Examples: International trade regime (WTO), industrial

standards, customs terminology and classifications, etc.

Integration means either a spontaneous process of merging economies due to the working of market forces or a deliberate policy aiming at abolishing discrimination between domestic and foreign good, services and factors of production. The latter can be carried out at different levels of ambition:

1) Trade preferences = partners lower trade barriers for certain or all goods between themselves, but not against third countries

2) Free trade area (FTA) = trade barriers are abolished between partners, but trade policy against third countries are not harmonised

3) Customs union = as FTA but members also have a common external trade policy

4) Common market = free movement of goods, services and factors of production 5) Economic Union = as customs union but also common currency and more or

Only the two first ones are realistic alternatives for Asia-Pacific at this stage. The only regional one up and working today is AEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA), which is strictly not yet a FTA since trade barriers, although low, still exist. Moreover Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) aims at free trade among its members, but the goals are vague and far away. Moreover there are some bilateral FTAs in the region if Australia and New Zealand are included, notably between Singapore on the one hand and Japan, Australia and New Zealand, respectively, on the other.

Organisations for co-operation and integration

This activity got started only slowly in the 1960s and 1970s. The early attempts often have a membership extending to more than East and Southeast Asia. ASEAN was the first intra-Asian organisation; see below. There were also a few “non-starters”, e.g. the Pacific Free Trade Area (PAFTA), which was proposed as a FTA between the developed parts of Asia-Pacific and the Organisation for Pacific Trade, Aid and Development (OPTAD) modelled on the OECD.

Important non-government organisations (NGOs)

Such organisations emerged from the late 1960s on. They tended to have a very small bureaucracy and loose political connections. This made participation possible from countries without formal relations (such as China and Taiwan).

• Pacific Basin Economic Council (PBEC); consists of national committees of leading business people (over 1000 firms are represented). Builds relationships between the regional business communities, aims at increasing trade and FDI and promote economic and social development. Advises (and lobbies)

governments as to development issues. Member committees from Australia, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Ecuador, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and the United States. Today PDEC is closely affiliated to APEC; see below.

• Pacific Trade and Development Conference (PAFTAD); private organisation

discussion of Asia-Pacific economic issues, and produces publications on international economic and development issues pertaining to Asia-Pacific.

• Pacific Economic Cooperation Conference (PECC); est. in 1980. The

members are officially private individuals, but the membership makes sure that the results of its deliberations reach the ears of the decision makers. The membership has a tripartite structure: Representatives from the business community, universities and government agencies. PECC is a regional forum for co-operation and policy co-ordination in order to promote economic development in the Asia-Pacific region. PECC is the only NGO official observer of APEC; see below. Gives analytical support and information to APEC. Member committees from: Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Ecuador, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, The Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Pacific Islands Forum, Taiwan, Thailand, United States, Vietnam.

Inter-governmental organisations

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), formed in 1989 and originally modelled on the OECD is a rather loose consultative forum, but with ambitions to form a free trade area by 2010 (for developed members) and 2020 (for developing members); also including free FDI movements. APEC is important because it accounts for about 40 percent of world trade and 50 percent of world production. It is weakened, however, by its heterogeneous membership. For instance, there have been conflicts as to whether the activities should be regulated by formal agreements or voluntary co-ordination and peer pressure. (Americans propose more formal structure, Asians a less formal.)

APEC is a discussion forum on trade and economic co-operation, and aims at

increasing co-operation between developed and developing countries, as well as being a counterforce against trade barriers and protectionism. It aims specifically at “open regionalism”, i.e. wants to avoid forming a closed bloc.

achieved. Committees, working groups and task forces provide a broad and largely informal contact surface for the member economies, however, and foster an ongoing dialogue.

Membership: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, China, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Russia, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, United States, Vietnam.

Important non-starter: East Asian Economic Group (EAEG) was mooted by then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad (Malaysia). The idea was to form an Asian

counterforce to the emerging blocs in other parts of the world and a common platform for the members in, e.g., trade negotiations. Non-Asian countries would not be

accepted as members.

Due to American (!) resistance the EAEG never materialised – a watered-down version the East Asian Economic Caucus (EAEC) was established instead under APEC but never became anything beyond rhetoric. Note, however, that the recent co-operation between ASEAN and Northeast Asia (the so-called ASEAN + 3 process, see below) may create something that resembles the original EAEG.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established in 1967 and is the most important regional organisation in Asia. All Southeast Asian countries are now members: Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand (1967), Brunei Darussalam (1984), Vietnam 1995, Burma and Laos (1997) and Cambodia (1999). Important schemes:

• AFTA (ASEAN Free Trade Area); most tariffs between members reduced to 0 – 5% by the end of 2002. A rule of origin of 40 percent is applied (i.e. at least 40% of the value of a product must originate in ASEAN in order to qualify for preferential tariff rates.) Aims at full abolishment of trade and, eventually, an ASEAN Economic Community by 2020, implying free movement of goods, services, capital and labour among members;

companies from two different ASEAN countries. It is not a legal entity but merely an "umbrella association" under the scheme wherein the output of the participating companies will enjoy a preferential tariff rate in the range of 0-5%” (ASEAN Secretariat);

• ASEAN Forum; security dialogue;

• ASEM (the Asia-European Meeting) was originally proposed by ASEAN;

• System with discussions with so-called dialogue partners at the

Post-Ministerial conferences (i.e., after the annual meetings of ASEAN’s economic ministers) on issues of common interests. Dialogue partners are: the US, Canada, the EU, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, China and India.

The benefits of AFTA are controversial. This is because trade may be diverted towards less efficient producers than would be the case under non-discriminatory arrangements. However, it is clear that making the region more attractive to foreign investors is more important as a goal of AFTA than increasing intra-regional trade.

ASEAN + 3; Inofficially implements the EAEC, but not a “real organisation” yet. Recognising the importance of establishing the same link with Northeast Asia and the important role that East Asian countries play in the region, the heads of state and government of China, Japan and Korea were invited to the Second ASEAN Informal Summit in Kuala Lumpur in 1997. The first “ASEAN+3” summit was followed by separate “ASEAN+1” meetings with the leaders of China, Japan and Korea.

ASEAN now regularly holds joint meetings – usually after ASEAN summits or ministerial conferences – with representatives of China, Japan and Korea on issues of economic co-operation. Free trade ASEAN-China is aimed at officially by 2010. For Korea and Japan (2012) the process has not gone that far, but in the case of Japan a framework agreement has already been signed.

ASEAN has also agreed to form a “partnership” with the “Closer Economic

Growth triangles

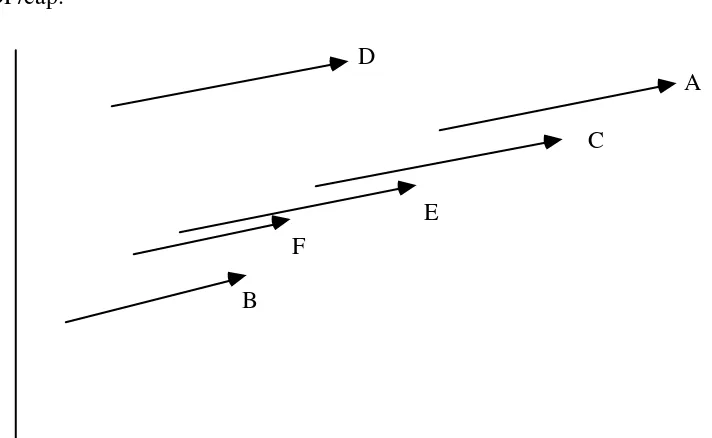

The process of regional integration in ASEAN has partly taken place through so-called growth triangles. The general idea is to link adjacent parts of two or several countries with different comparative advantages based on, e.g., differences in technology, labour endowment, natural resources, capital etc., to form a sub-region conducive to growth. Such a growth triangle is “borderless” regarding goods and capital movements, although there remain barriers against the movement of labour. Thus large wage differences remain part of the picture.

The first, and most important, such “triangle” the Singapore-Johor-Riau (SIJORI) area was conceived after 1988 with a revision of investment regulations in Indonesia. At first the development was mainly based on joint ventures between Singapore

government-linked companies and the Indonesian private sector. Subsequently MNCs based in Singapore began to locate investments in Batam and Bintan (in Indonesia), which both can offer land and labour at low cost. The cost of labour in Riau province is only about one-fifth of that in Singapore and land is very cheap compared to Singapore, too. Business grew rapidly after development of infrastructure and transport links.

The greatest impact of the SIJORI triangle has been in Batam. Relations between Singapore and Johor are much older than the Growth Triangle concept, for historical reasons. Companies from Singapore moved to Johor before there were any formal agreements because of the short distance and cultural closeness. However, the third leg of the triangle, the Johor-Riau link is still weak due to the alleged lack of

complementarities and the physical distance. The central government in Malaysia has also been less interested in the project than Indonesia and Singapore.

Other attempts at forming growth triangles:

In ASEAN

• Penang (Malaysia) – Sumatra (Indonesia) – South Thailand (the “Northern Triangle”)

These are far less important and have to a great extent remained in the level of rhetoric only. One problem is that they lack an important hub like Singapore.

In East Asia

• Guangdong & Fujien provinces (China) – Hong Kong – Taiwan

• The area around Tumen river: China – Korea – Russia

Appendix 1.

THE ENDOGENOUS STATE AND ECONOMIC

DEVELOPMENT: A SURVEY

International Journal of Development Issues,

Vol. 1, No. 2, 2002

Hans C. Blomqvist

Swedish School of Economics and Business Administration POB 287

FIN-65101 Vasa Finland

E-mail: [email protected]

Tel.: +358-6-3533 734

Introduction

The history of post-war economic development is mostly rather depressing reading in that there are few success stories. There are some, however, most of them East Asian1. Even the recent serious recession cannot wipe out the enormous progress that took place over preceding decades in these countries. Because of this there is now a voluminous literature on what has sometimes — rather misleadingly — been called “the Asian model” (see, e.g. Islam 1994, Jomo 1997: 27, 157), aiming at finding out its “secrets”.

Much of the discussion has evolved around the relative importance of market forces versus government interventions (cf., e.g., Aoki et al. 1997: 1, Smith 1995, World Bank 1993). In the context of explaining the successful Asian development it is possible to distinguish roughly between two groups of authors, the “neo-classicists” and the “structuralists” (or “statists”) emphasising either the role of the free market or the selective interference of governments.

The dichotomy between “state” and “market” is, however, unfortunate in two respects. Firstly, the importance of interaction between market forces and institutions, mostly created by the state, is obscured by this distinction (cf. Zysman and Doherty 1995). Due precisely to a complicated interaction of this kind we can observe many different types of development patterns, not least in Asia, which all seem to be viable. Secondly, the role of the state has mostly been seen in a traditional instrumental perspective by both neoclassicists and statists. The proper role of the state is presumably one of identifying and correcting market failures, according to the neoclassical approach (cf. the approach taken in, e.g., Balassa 1991, World Bank 1993, 1997) and one of “governing the market” (Wade 1990) according to the structuralist approach. In both cases government interventions may be misguided and excessive and create distortions and “rents” which are potential sources of additional distortions (c.f. Islam 1992). What then determines what types of interventions are actually undertaken and to what extent? It seems like mainstream economics has been slow at addressing those problems.

The weakness of traditional economic analysis of the state in economic development has been the neglect of the endogenous character of the public sector. Hence it has not been taken into account why politicians and state bureaucracy behave as they do to the extent it deserves. Similarly, the fact that both markets and governments are constrained by institutions (“rules of the game”) which, in turn, evolve in interaction with them (North 1993), is often neglected. An obvious consequence has been difficulties to explain why some countries develop and some do not.

A third way, the institutional approach to economic development has been the subject of much interest recently and there is now a rapidly increasing body of literature on the topic (for an excellent recent overview, see Clague 1997). East Asia, with many different types of state, as well as a (mostly) outstanding development record, appears to be a particularly interesting object for case studies on the role of the state in development.

1

The focus of this paper is thus on the developmental role of the “state”, a term that is used here to denote the group of people, government and core bureaucracy that make and implement decisions in the name of the public interest. For simplicity I will use the terms “state” and “government” interchangeably, even though there may, in principle, be objections to this. The emphasis of the paper is on a theoretical survey of the state in interaction with the surrounding society, where the occasional illustrations are mostly taken from the Asian experience.

The state and economic development: a historical overview

The role of the state as an agent of development has been perceived very differently in different times. The basic proposition, that the state indeed has a role to play in economic development has mostly been taken for granted, however. The basic justification for a state as the body that defines and enforces property and contract rights and provides public goods such as law and order and defence has been uncontroversial. The same is largely true for so-called functional interventions (Jomo 1997: 119, Lall 1996: 5) when the state steps in to correct market failures. Other typical fields of state intervention, like income redistribution, stabilisation and selective industrial policy, have been much more controversial, even if most states in reality are involved in all of them.

Analytically, the state has mostly been treated in a similar way in economic analyses no matter how its proper role has been interpreted, that is, as an exogenous and basically benevolent monolith that intervenes in the economy in order to improve its functioning. Accordingly, the approach has usually been to find appropriate and well-defined means to reach equally well-well-defined targets. Policy failures have been explained in terms of imperfect information or lacking capability of the state apparatus (cf., e.g., Lall 1996: 21, World Bank 1997: 2–3) while successful interventions have not required any particular explanations as the prescribed instrument has produced the expected result.

Imperfect information and implementation costs certainly play a role when explaining policy failures. Some policy measures (such as devaluations) are relatively easy to carry out, from an administrative point of view, while others (such as tax reforms) are much more demanding (cf. Krueger 1993: 68). The more complicated tasks a government takes on the more obvious is the risk of failure. The problems are typically much more prevalent in developing countries with limited human resources which may be spread too thinly as a consequence of too ambitious government programmes. As argued in this article, there are other reasons for poor policies as well, however. In particular, the state need not be benevolent in the first place and what it “wants” is typically determined by a complicated interplay of factional interests.

the state. Command economies of the Soviet type also seemed to be successful at the time, and were then perceived as a serious challenge to the market system (cf., e.g., Krueger 1993: 39, 42).

In the specific context of economic development, the dominating view was that ill-functioning markets and “vicious circles” prevented industrialisation and other development. The market was perceived as part of the problem, not part of the solution (see, e.g., Srinivasan 1985). Hence, the markets alone could not be relied on for achieving growth and development. Instead, it was held that only a strong and well co-ordinated effort by the state could bring about development. This implied a large public sector as well as extensive interventions in the private sector (see, e.g., Blomqvist and Lundahl 1997).

An important and far-reaching result of this thinking was the import-substitution (IS) model of industrialisation, prescribing industrialisation behind trade barriers. This model was — largely because of the mistrust of markets — frequently combined with a good deal of central planning and regulations of, e.g., prices, wages as well as foreign trade and capital flows. Government officials were thought to be able to foresee which industries would eventually be viable and were expected to set up incentives for promoting them (Krueger 1993: 48). In countries with an elite leaning towards Marxism the ideal was to eliminate the market mechanism to the greatest extent possible, although this could seldom be fully accomplished in practice.

Although the import-substituting model remained dominating for a long time, it was met by increasing criticism, although little was actually published before the 1970s (Hicks 1989). The reasons for the criticism can be found both in theoretical developments and in the unfolding empirical experience of applying the model. Together they produced the so-called neo-classical counter-revolution of development economics (Toye 1987). Policy-induced distortions in the economy, “government failures”, which were seen as a more serious problem than the deficiencies of the market system by the representatives of this “school”, became the focus of attention in work by, e.g., Lal (1983); see also Srinivasan (1985).

A major interpretation problem with these government-induced distortions is that their detrimental effects are often evident, so the question then is why they are undertaken at all. The seemingly obvious conclusion — that economic agents may be as selfish when operating in the public sector as they are regularly assumed to be in the private sector — did not seem to occur to researchers. The traditional way out instead is to point at “non-economic” or “political” factors. Since this introduces a “black box” — as well as a tautological element — into the argument it is not an entirely satisfactory solution, however.

took some time before it became evident what was going on in the first place (cf. Hicks 1989). The reason for the switch of strategy was hardly an inherent market-friendly conviction of the governments of these countries, however, but it happened rather because they met constraints — such as a small home market — that forced them out of the IS paradigm.

The planned economies proper also performed poorly which induced half-hearted and largely unsuccessful attempts at reforms. After lagging behind more and more the system — at least in its Soviet version — broke down altogether (see, e.g. Winiecki 1991). Both in the case of import substitution and in the case of central planning, rent-seeking interest groups and a self-serving state, with hindsight, appear to have played a key role in the failure.

As a consequence of the apparent defeat of the interventionist approach due to related “government failures”, the ideal of a “minimalist” state became fashionable both among academics and international agencies (see Chang and Rowthorn 1995: 7–19, Hicks 1989, Martinussen 1997: 263). Except for granting basic public goods, such as law and order, and institutions like a system of property and contract rights, the state should stay out of the economy, according to this view. Several important international agencies, especially the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, became proponents of this approach, and many academics explained the successful development of many East Asian countries as a consequence of adhering to the basic principles of the market system (cf., e.g., Balassa 1981, Burenstam Linder 1986, Chen 1979. See also Chiu and Lui 1998 and Friedman and Friedman 1980).

Several recent developments have challenged this “neo-liberal” ideal of an non-interventionist government. Theoretical research, especially within the so-called new institutional economics paradigm, has been instrumental in changing the views on the potential role of the state. A central contribution of this approach is its emphasis on the importance of “efficient” institutions2, many of which are created or supported by the state (cf., e.g., North 1997, Chang and Rowthorn 1995, Clague 1997). In other words, even if reasonably undistorted markets have an indisputable role in a successful development strategy a well-functioning market economy also presupposes the support of institutions.

Again, however, a major reason for reconsidering the ideal of the “minimalist” state was empirical. Firstly, the unprecedented success of the East Asian economies became subject to closer scrutiny and was partly re-interpreted. Many of these countries represent strongly interventionist states, suggesting that the laissez-faire

approach may not be the optimal one when rapid economic development is called for. There are indeed good reasons to believe that the need for interventions by the state is stronger the less developed the country is (Reinert 1999). (In other words, East Asia has been invoked as an example of both market-led and government-led growth.) Such sentiments have been expressed, of course, for quite a while with Chalmers Johnson as one prominent, but far from the only example (see, e.g. Johnson 1982). Secondly, the spectacular lack of success in many transition economies, particularly the former Soviet Union where the state is weak and passive and the institutional

2

framework undeveloped, underlines the importance of well-functioning government (and other) institutions.

Recently we have perhaps witnessed the beginning of a new swing of the pendulum, when the once solid growth of East Asia plummeted in 1997. Even though this was arguably a short-term disturbance, it rekindled the discussion on state versus market once again, this time with a more critical view on the activities of the state. All government measures need not be beneficial for development, not even in successful economies, and the extent of interventions may be less important than their “quality” (cf. Chiu and Lui 1998).

The endogenous state

Theoretical development from the 1960s on eventually improved our understanding of the “non-economic” factors behind seemingly irrational and distorting government policies. Emerging theory in the realm of political economy, above all Mancur Olson’s work on interest groups (Olson 1965), the theory on public choice (Buchanan and Tullock 1962) and rent-seeking (Krueger 1974, Bhagwati and Srinivasan 1983), etc. contributed to a new and more complex view on the role of the state. Another issue, indirectly related to this was the question of culture as a factor behind economic development. In the case of East Asia the potential role of the Confucian ethic (and, later, so-called Asian values) has been widely discussed, starting from the contribution by Kahn (1979) but with rather inconclusive results.

The institutionally inclined economist typically had a rather negative view on the role of the state to begin with. The state is allegedly represented by largely self-serving politicians and officials, who see more to their own interest than to that of the general public. Interest groups, in turn, put pressure on the state in order to obtain favours and are willing to pay for these in various ways. Outright corruption is not unusual. Resources are wasted in the process and the outcome is likely to be distorted. In the extreme case the state itself becomes the dominating interest group with the aim of maximising the revenue of the ruling elite while giving little or nothing in return. This is the so-called predatory state. In other cases, however, the state seems to have contributed considerably to a positive economic development, which seems to suggest that there may be checks and balances that may direct the inherent selfishness of decision makers into favourable activities from the society’s point of view. This seems to have been the case especially in East Asia.

“will” of the state is formulated through competition between different factions and their interaction with non-state actors (cf., e.g., Clark and Roy 1997: 6).

Thus if the state behaves in a way that seems inoptimal, it is not necessarily because the “right” kind of action is unknown. In fact, it is fairly easy to state the basic prerequisites for favourable economic development: reasonably undistorted markets, a stable macroeconomic environment, a high rate of investment in physical and human capital, provision of basic public goods and institutions (cf., e.g., World Bank 1993, ch. 2). Favouring specific firms and sectors through suppressing competition seems, in turn, to be a certain recipe for failure.

Adhering to the general principles of development promotion just outlined still gives a great deal of leeway to the policy makers as to what type of policy they prefer to pursue. Empirically, of course, the experience of the state as an agent of development varies a great deal. In East Asia, in particular, the experience of strongly intervening states has arguably been encouraging, even if it remains controversial to what extent interventions really have been a major reason for the rapid development (cf., e.g. World Bank 1993, ch. 2). There are many examples of interventionist states that have been much less successful, however while some Asian economies have been successful with a minimum of intervention.

Understanding the mechanisms that lead to more or less successful state activities would be important indeed. Even if a good deal of research has been done in this realm, the mechanisms are still far from fully understood. Considering the East Asian region only, it is evident that the degree and type of interventionism have been very different in different countries and that excellent results seem to have been compatible with very different policy stances. The cases of Hong Kong and Singapore are instructive here as the former relied heavily on the markets while the latter had much more government interference. Nevertheless both have reached about the same level of GDP per capita. Another illuminating pair would be Thailand and Malaysia, where the latter has had a much more interventionist government but both have been able to display very high growth rates.

Thus it is hard to see a clear relation between the degree of government intervention

per se and development. An active government is no guarantee for good governance. The important thing, instead, is what kind of interventions is carried out, and this, in turn, depends on the motives of the political elite to intervene in the first place. As noted by North (1979), the creation of a state is, on the one hand, a “precondition for economic growth”; on the other hand the state is the reason for “man-made decline”. In order to understand its role it has to be “endogenised”, i.e., it is necessary to analyse the motives and incentives of the individuals that are entitled to act in the name of the state and their interaction with the surrounding society. This interaction is constrained by various institutions.

contribution observes that states with relatively good institutions are able to grow rapidly due to the catch-up effect and they do not have to be particularly benevolent in order to do so (Olson 1997).

Basic cultural values may have a deep influence on the formation of institutions and choice of policies (cf. Hicks 1989, Lal 1998a). Hence the institutional structure may differ widely in different countries due to the fact that institutions are formed as a result of an evolutionary process. To some extent institutions are also an outcome of deliberate design by the elite, however (Robinson 1998), largely depending on the room for manoeuvring it has. Hence, poor institutions are not necessarily due to incompetence and ignorance but can be a consequence of rational decisions by the those in power aiming at promoting their selfish interest before that of the society.

Types of state—a simple taxonomy

In order to understand the actual behaviour of a particular state it is useful to classify different types of states into different groups, depending on the ultimate goals of the state and on the kind of popular support it enjoys. I will use a classification scheme originally proposed by Lal and Myint (1996) and later modified by myself (Blomqvist 1998, 2000). I assume here, somewhat simplifying, that a state always can promote development if it wishes to do so. While this may not always be the case, it is highly doubtful whether differences in developmental capability can explain systematic differences in development record (Robinson 1997). The classification, of course, identifies ”models”, not real states, which more often than not display characteristics from more than one category.

On the one hand, a state can be classified according to its “benevolence”, i.e. whether it is genuinely oriented towards economic development or not. Depending on this, a state can be either “developmental” or “predatory”. The ultimate objective of the predatory state is to maximise the welfare of the ruler or ruling clique.

On the other hand, a state can be either autonomous or dependent (or factional, according to the terminology of Lal and Myint 1996). The autonomous state is insulated from the pressure of special interests, but also from the electorate at large, and is able to set its own objectives independently, while the dependent state functions as an instrument for an electoral majority or a special interest group that happens to be in power at the moment (see Lal and Myint 1996) and whose behaviour reflects collective decision making subject to various constraints (Krueger 1993: 59). An autonomous state is non-democratic by definition while a dependent state may, but need not be democratic.

Combining the two principles of classification gives us a taxonomy, illustrated in

Figure 1 Types of State

A u t o n o m o us

D e v e l o p - m e n t a l

P r e d a t o r y

G u a r d i a n Parl i ame ntary de mocracy

A b s o l u t i s t

B u r e a u c r a ti c- a u t h o r i t a r i an

Hijacked Dependent

Source: Blomqvist 2000.

The “guardian state” is developmental and inclined towards maximising the “welfare” of the society (including, of course, the elite) as the state perceives it. (As the ideas as to what constitutes the best for a country may sometimes be rather peculiar, a guardian state is not necessarily “benevolent” in the common sense of the word (cf. Krueger 1993: 60).)

Since it is independent of the electorate, the guardian state is not democratic, although some democratic institutions may be entertained. Basic Confucian ideals are compatible with this type of state, even if such ideals are by no means necessary or sufficient to bring about such a model. In Asia, Hong Kong under the last decades of British rule may serve as an example of this type of state. Singapore has been mentioned as a case in point as well (Lal and Myint 1996) but is actually a more complicated case (see, e.g. Low 1998).

The democratic version of the partial state can a priori be assumed to be more developmental than the authoritarian (predatory) type. Whether it is necessarily more developmental than any autonomous state is a moot point, much discussed in the context of East Asia, see, e.g., Clark and Roy (1997: 151), Lal (1998b), Low (1998: 22–36), McGuire and Olson (1996), Okuno-Fujiwara (1996: 403). One reason speaking for democracy in this context, according to McGuire and Olson (1996), is that a majority in a democratic society earns some market income in excess of its tax income. The argument seems rather unconvincing, however, since it is not unusual that the ruling clique of authoritarian, predatory regimes earns a market income as well (cf. the “crony capitalism” in the Philippines under Ferdinand Marcos).

the power of the elite to tinker with property and contract rights (Clague et al. 1997). This is not really the case with autonomous governments, where there is always a risk that the state changes the rules in its own favour (cf. Olson 2000:36). Moreover, there are usually built-in checks such as a constitutionally determined division of power. The democratic system is also, as a rule, more transparent than other systems because the flow of information is less controlled.

The characteristics just mentioned make abuse of power more difficult although “grey areas”, such as financial support to party-controlled organisations, political appointments and rent-creating regulations, may remain. There is no reason to believe that a democratic government, a priori, would be entirely free from predatory traits compared to other forms of government, although it may be more constrained and although predation may take on different forms (cf. Lal 1998a: 122). Pressure groups may concentrate their efforts on certain parts of the government, or even certain key officials, who may affect decisions in a direction favourable to the groups through, e.g., passing on selective information (Tirole 1994). The need of a democratic government to court key interest groups in order to get re-elected is also widely believed to increase the size of the public sector and its interventionist stance over time, with doubtful effects on allocative efficiency and economic development (cf. Doshi 1996). Thailand or the Philippines of today may be good examples of a democratic, partial state.

The autonomous predatory state can, according to Lal and Myint (1996), be of two types. In an absolutist state the full authority of the state rests with a ruler (a king, dictator or colonial power) and the raison d'être of the state is maximising the welfare of this ruler. The Philippines under Marcos or, possibly, Indonesia under Suharto may perhaps be used as examples here, even if much more extreme cases can be found in other parts of the world.

In the bureaucratic-authoritarian type of state a dominating group wields the power in a more or less collective manner. The group referred to may be a political party, or an ethnic or religious group. Bureaucratic-authoritarian states are often one-party states where maximisation of public employment is a means through which the ruling group attempts to maintain support (cf. Krueger 1993: 63). The remaining “socialist” countries in the region may be mentioned as examples in this case. Obviously, the distinction between the two main types of autonomous predatory states may not always be sharp. In both cases, the bureaucracy itself may be rent-seeking as well, which is easier if the costs of monitoring it is high, which often is the case in developing countries (cf. Sartre 1998). This adds, of course, to the predatory character of the government and to its detrimental effects.

instruments of power but if the time horizon of the ruler is short enough he may still prefer to steal from the citizens instead of developing the economy (Olson 2000:26).

The dependent predatory state, the "hijacked" state, finally, is based on smaller coalitions or cliques that are able to capture the state for longer or shorter periods of time with the aid of brute force or superior financial resources. Many military regimes have been of this type and so have some ethnically based governments in multi-ethnic societies. Factional rivalry among a powerful landed oligarchy may produce a similar result as may powerful private companies (Hellman et al. 2000). In this case, there is very little that keeps the government from turning predatory. The partial state is inherently unstable which implies that it probably has little to gain from economic development and indeed from taking into account the consequences of its actions on the economy as a whole. China, between 1911 and 1949, is a case in point.

Evolution of the type of state

From the point of view of development it is interesting to look into reasons why a state comes to be of a certain type, and what mechanisms may take a state from one type to another, for, example, from a partial to an autonomous predatory state, and further to a more developmentally inclined one and perhaps on to a multipolar democratic one. Although some research has been done on that, our knowledge is still far from complete.

The type of state that can be found at a given moment of time is an outcome of an evolutionary process, where the basic endowments of an economy interacts with developing institutions and where the bargaining power of organised groups play a central role. Rules tend to be changed when the bargaining power changes (Voigt 1998). As a rule, the intrusive role of the state tends to be reduced and becomes more indirect as the economy becomes more developed (Reinert 1999).

The “hijacked” state is likely to be the worst alternative from the development point of view since it is weak and thus very unstable (cf. Lundahl 1997). As noted already, the ruling clique tends to concentrate on extracting as much income as possible in the short run without paying much attention to the overall effects on the economy. The result is bound to be ambiguous and distorted property rights as well as lack of any commitment on the part of the state, leading to a situation where the incentives promoting productive activities are minimal. Even if the social return to such activities is likely to be high the prospects for private gains are poor. This type of state is characteristic for a situation when several factions compete for power but all of them are too weak to be able to hold on to it for more than a short time. The end result is often a total break down of the state apparatus. The situation is not unlike that in Cambodia after the Vietnamese occupation, where the international community (viz. the United Nations) in effect had to take over the role of the state.

or be able to acquire, a large stake in the economy. It is easy to show that the larger the share of the economy the elite controls, the less distorting its policies are likely to be (Olson 1982: 41-44). This is because it stands to gain more from growth (and lose more as a result of declining production that may follow from predatory behaviour) if it controls a large part of the economy than if it only controls a small part.

It can also be shown that a predatory state has an interest in providing collective goods that enhance the productivity of the private sector, if the increase in income can be expropriated, fully or partly, by the ruling elite (see, e.g., Findlay and Wilson 1987). In that case the government should normally aim at maximising the national income. In the case of a bureaucratic-authoritarian state, for which a central way of distributing favours to the members of the ruling elite is through public employment, there is a tendency for the public sector to grow excessively, however, as all state revenue is spent on employing more government staff (Blomqvist and Lundahl 1997).

The prospects of economic gain may thus discipline the state to behave in a reasonably restrained fashion. If the economic incentives for a state to promote economic growth, by means of prudent macroeconomic policy, provision of public goods and efficient institutions, are strong enough, it may develop towards a guardian state. The probability and the time pattern of a positive response to policies are likely to be a crucial factor. Obviously, the discount rate of the government is important here. If the risk of being thrown out of office is high the discount factor tends to be large. Then it is more or less irrelevant for the ruling elite what is going to happen in the long run. The optimal strategy for the government is to concentrate on expropriating as much as possible, as quickly as possible.

While the idea of development prospects is an intuitively attractive one it may not explain all cases of developmental governments. In fact, the Asian NIEs are all examples of countries, which were not regarded by the experts as promising candidates for rapid development in the late 1950s and early 1960s (cf., e.g., Blomqvist and Lundahl 1997, Hicks 1989). In fact, their favourable development went unnoticed, by and large, until the 1970s. Ex post we know, of course, that these countries are just about the best examples of successful development that can be found. An important reason for this seems to be that all Asian NIEs developed under a serious external threat. A strong economy was then a prerequisite not only for the government’s ability to stay in power, but also for the survival of the state as such. National security and economic development are then two sides of the same coin (see, e.g., Gunnarsson and Lundahl 1996, Gunnarsson and Rojas 1995: 103–104).

Another factor pertaining to the inclination of an authoritarian government to be developmental appears to be the endowment of natural resources. Since these are relatively easy to exploit within enclaves even with a poor general level of infrastructure, a rich endowment of resources may, in fact, encourage predatory behaviour of the state (cf. Robinson 1997, Leite and Weidmann 1999). This may well have been one of the factors behind the delay in development in the large ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries as compared to, e.g., the Asian NIEs, which were all resource-poor.