Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 00:04

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Fostering Creativity in Business Education:

Developing Creative Classroom Environments

to Provide Students With Critical Workplace

Competencies

Michaela Driver

To cite this article: Michaela Driver (2001) Fostering Creativity in Business Education: Developing Creative Classroom Environments to Provide Students With Critical Workplace Competencies, Journal of Education for Business, 77:1, 28-33, DOI: 10.1080/08832320109599667

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320109599667

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 202

View related articles

Classroom

Fostering Creativity in Business

Education: Developing Creative

Environments to Provide

Students With Critical Workplace

Competencies

MICHAELA DRIVER

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

East Tennessee State University Johnson City, Tennessee

reativity has been identified as a

C

critical dimension in making orga- nizations successful today (Miller,1987; Miller, 2000; Robinson

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Stern,1997). In fact, creativity has been declared essential for a business’s long- term survival (Robinson & Stern, 1997), and an organization’s ability to “pro- mote and guide” creativity has been identified as business’s “greatest chal- lenge’’ in terms of survival and prof- itability (Miller, 1987, p. 4). Conse- quently, creativity, which has been defined as employees’ engaging in valu- able activities for improvement at their own initiative (Miller, 1987), is a com- petence that many organizations strive

for today.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

As consumers become lessand less loyal, as competition from around the world intensifies, and as the Internet provides unlimited consumer choices, more and more business orga- nizations are discovering that being cre- ative and consistently delivering a prod- uct or service that delights customers in ever-novel ways is fast becoming their only sustainable advantage in the mar- ketplace (Miller, 2000).

The increase in organizational inter- est in creativity has in turn resulted in more published research on the creative organization. This literature has focused

ABSTRACT. This article explores the value of exposing students to creative classroom environments in business education to prepare them for creative workplaces. A study of student percep- tions in four undergraduate business classrooms indicates that dimensions

of creativity training, such as providing time and rewards for creativity, stimu- lating risk taking, diversity of thinking, cooperation, and questioning of assumptions, can be effctively integrat- ed into business education.

on where and how creativity occurs in organizations.

Parameters of Organizational Creativity

Parameters or characteristics that have been identified as facilitating cre- ative behaviors in organizations range from structural to cultural variables. Structural variables refer to organiza- tional systems or procedures, that is, generally objective and perhaps tangible dimensions, whereas cultural variables refer to an organization’s values, beliefs, and customs, subjective vari- ables relating to the social context.

On the structural side, systems that support creativity, such as interactive information technologies and reward and budgeting systems, have been iden-

tified as important (Miller, 2000; Robin- son & Stern, 1997; Woodman, Sawyer, & Griffin, 1993). On the cultural side, perceived organizational support for creativity, tolerance of differences, strategic alignment, allowing for self- initiated and unofficial activities, capi- talizing on serendipity, fostering broad communication and exposure to diverse stimuli, knowledge sharing, and the ability to delay judgment have all been identified as critical factors for organi- zational creativity (Bernacki, 2000; Miller, 2000; Robinson & Stern, 1997; Siege1 & Kaemmerer, 1978).

The greater number of variables iden- tified on the structural versus the cultural side indicates that cultural variables apparently are more critical than support- ing structures in fostering the creative potential of an organization’s employees (Bernacki, 2000). Certainly, organiza- tional creativity depends on employees’ having the proper resources, such as ade- quate time for creative thinking and money to experiment (Nohria & Gulati, 1996) or adequate information technolo- gies and flexible structures that encour- age collaboration (Woodman et al., 1993). However, cultural variables such as environments that welcome creative ideas without exerting control or that

20

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for Businessencourage risk taking and questioning of assumptions may be even more critical

(Buchen, 2000; Dess

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Picken, 2000).In particular, the following cultural dimensions have been advanced as

essential for creative organizations: per- ceived support for creativity, especially at the top (Amabile, 1988; Eisenberger, Fasolo, & Davis-LaMastro, 1990; Siegel & Kaemmerer, 1978), encouragement of diversity in perspectives (Bernacki, 2000; Dess & Picken, 2000; Miller, 2000; Siegel & Kaemmerer, 1978), and the freedom to take risks and initiate unofficial activities (Dess & Picken, 2000; Miller, 1987; Miller, 2000; Robin- son & Stern, 1997). Thus, a creative organization has values, beliefs, and norms that encourage creative behaviors. It encourages diversity of membership and viewpoints and fosters members’ beliefs in the safety of experimenting and handling projects outside of their normal area of responsibility or the normal busi- ness process, even if mistakes are made. Rather than referring to any particular attribute or structure, creativity as an organizational characteristic refers to an environment that facilitates individual and group creativity.

Organizational creativity may be improved by either maintaining and enriching the organization’s culture in support of creativity or by increasing the likelihood that employees will exhibit creative behaviors once exposed to a favorable environment. The latter sce- nario can be encouraged through busi- ness education, which presents a rich and perhaps untapped opportunity for organi- zations. More creative educational envi- ronments will provide more valuable human capital to prospective employers through better preparation of students for their membership in organizations.

Unlike creativity in art or music edu- cation, creativity in business education is not an end in itself, as the primary purpose of business education must still be to provide relevant business knowl- edge. However, because it has become critical in nearly all aspects of the busi- ness process and daily work activities (Robinson & Stern, 1997), creatihy, much like diversity and globalization, should be considered as one of several dimensions commonly included in mainstream business courses such as

Introductory Business Management and Organizational Behavior (Palmer, 2000). In addition, the value of adding creativity as a dimension of business education is not so much in teaching it

as a subject, but rather in providing cre- ative environments that simulate those that students are likely to encounter in the workplace. In fact, studies on encouraging creativity in students have shown that the development of creative classroom environments is critical for students’ propensity to engage in cre-

ative acts (De Souza Fleith, 2000).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Benchmarks for Creative Behavior

In this article, I describe how the business education setting can serve as a practice field for students’ future organi- zational experiences involving creativi- ty. More specifically, I present ways in which classroom instruction in a wide variety of business courses can help stu- dents respond to creative environments and practice their creative abilities. Suc- cess will depend on the degree to which the classroom exhibits these characteris- tics. Steps for fostering creative behav- iors in the classroom include (De Souza Fleith, 2000):

1. Allowing time for creative think-

2. Rewarding creative ideas and prod-

3. Encouraging sensible risks 4. Allowing mistakes

5. Imagining other viewpoints 6. Encouraging explorations of the

7. Questioning assumptions

8. Refraining from evaluating/judging 9. Fostering cooperation rather than

0. Offering free rather than restricted

1. Encouraging dissent and diversity

2. Setting students up for success

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3. Requiring little if any rote learning

Like the characteristics of creative organizations, the factors that encourage creative behaviors in the classroom are more cultural than structural. They focus on the atmosphere, values, beliefs, and norms rather than setting up systems or

ing

ucts

environment

competition

choices

rather than failure

providing specific resources (other than the time required to implement the char- acteristics). Creativity in the classroom has been advocated as a critical success factor for students entering an increasing- ly diverse, rapidly changing, multination- al workplace (Palmer, 2000). Much like creativity in organizations, creative stu-

dent behaviors are seen less a

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

9a functionof individual characteristics and more as the product of an environment that stimu- lates creativity (De Souza Fleith, 2000; King Mildrum, 2000). The creative class- room offers various positive benefits, ranging from higher student achieve- ments to better learning skills (Palmer).

Consequently, I propose that a class- room environment that implements the steps described above will produce cre- ative behaviors in students more effec- tively than other classroom environ- ments. In turn, students who feel more encouraged to exhibit creative behaviors in the classroom should respond more favorably to other creativity-stimulating environments, such as those in creative organizations.

Method

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Subjects and Procedure

I studied four undergraduate manage- ment courses that I taught at a regional university in the Southeastern United States. The courses were all part of the standard management curriculum and included Organizational Behavior (MGT 3000), Advanced Organizational Behav- ior (MGT 4010, sections 1 and 2) and Organizational Theory and Development (MGT 4020). The students were college juniors or seniors, and the courses were structured to develop a creative environ- ment in the classroom. Assignments and class activities were designed to encour- age creative behaviors in individual stu- dents as well as in student groups. I pre- sented lecture materials in a manner encouraging diverse perspectives, cre- ative reflection, questioning of assump- tions, and multiple interpretations. Class discussions and student participation encouraged diverse perspectives, cooper- ation, and lack of judgment, and students were recognized frequently for creative approaches. I used the following tech- niques, corresponding to the 13 dimen- sions identified above:

September/October 2001 29

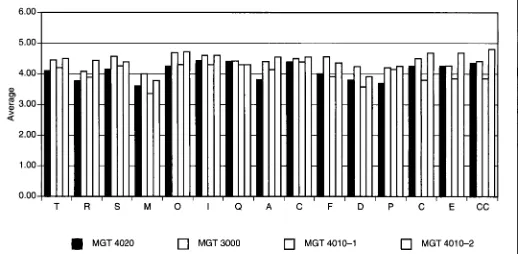

FIGURE 1. Average Responses for Each Survey Item, Across the Four Courses

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

6.00

I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

a,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

$

3.00 2.001

.oo

0.00

I

RS M O

MGT4020

O M

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Nore.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Please referzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

to Table 2 for definitions of dimensions.I

QzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

T 3000

A C

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

0

MGT 11 0-1zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

cl

E ;T 40’

cc

,2

1. Allowing time for creative think- ing. I provided in-class time for individ- ual and group exercises encouraging idea generation.

2. Rewarding creative ideas and

products. I reviewed outcomes of group and individual problem-solving activi- ties with the entire class and pointed out creative approaches, praising them and explaining how they add value to the problem-solving process.

3. Encouraging sensible risks. I encouraged class members to take unique and different approaches in vari- ous class exercises and group activities and rewarded any efforts in this direc- tion, particularly if they did not work as intended, and recognized them as learn- ing experiments.

4. Allowing mistakes. Any class member trying out a new idea or approach and who made a mistake was never ridiculed or even judged. The class was encouraged to treat different approaches with respect.

5. Imagining other viewpoints. I would present one viewpoint on any subject and then invite the class to come up with alternate scenarios that would either support or disprove any theory presented. I also made a point of regu-

larly asking students to reflect privately on what was just presented and to imag- ine applications that would provide alternative ways of conceiving the ideas presented.

6. Exploring the environment. I reg-

ularly asked students in class and via written reflective assignments to explore how the ideas they learned in class relate to their own personal expe- riences and the world they live in. I asked them to be alert for how certain dynamics in their groups and in their personal lives related to the theories investigated in class, thereby stimulat- ing their curiosity about how all of the ideas presented could be explored further.

7. Questioning assumptions. As stu- dent comments were solicited in class, I used probing questions to make the assumptions behind those statements transparent. In addition, several individ- ual and group exercises were used to show how students normally solve prob- lems or approach various issues covered in the courses. This was followed by extensive discussions on how the same processes could be done differently and what this shows about the participants’ assumptions.

8. Refraining from evaluating/judg-

ing. All exercises and discussions as well as any feedback on written assign- ments with regard to creative ideas or approaches were kept in a strictly non- judgmental tone. I frequently stressed that the activities were not about perfor- mance but exploration and probed the students for additional ideas.

9. Fostering cooperation rather than competition. I framed any exercise in class as well as class discussions as a cooperative learning effort and acted as a facilitator, intervening whenever com- petitive tendencies arose and reminding the class that the exercise was not about winning but about learning.

10. Offering free rather than restrict- ed choices. Any activity related to cre- ativity was kept as unstructured as pos- sible. I allowed the students to decide how to perform each task but provided encouraging and stimulating feedback when they requested it. I also solicited input from students on how they thought that several activities should be carried out.

1 1. Encouraging dissent and diversi- ty. Several exercises in class were designed for role-playing negotiations in diverse settings, and I regularly

30 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessTABLE 1. The Survey Instrument

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

This is a survey to find out about your thoughts on the creativity of your classroom environment. Please note that this is not

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

a test andthat there are no right or wrong answers. Just try to find the answer that most matches how you really feel about something. Please fill out the following survey by marking an X in the answer slot that best describes how you feel about a particular statement. Please note that:

I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

= Strongly disagreezyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2 = Somewhat disagree 3 = Undecided 4 = Somewhat agree 5 = Strongly agree

1. During this class, I was given time for creative thinking.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2 . I felt that I was rewarded for creative thinking.

3. I thought that when I was asked to be creative, taking some sensible risks was acceptable.

4. When I was asked to be creative, I was not afraid to make mistakes.

I

5. I was frequently encouraged to think about other viewpoints besidesthe most obvious one or the one I felt most comfortable with. 6. I was encouraged to explore ideas.

7. During class discussions and in the lectures I was encouraged to question the way I would normally see things.

8. My creative ideas were received with an open mind by the instructor.

I

9. During class activities there was quite a bit of cooperation among students.

10. When asked to be creative, I felt that I was free to make my own choices.

I 1. During class discussions and other activities that encouraged us to be creative, I did not feel pressured to conform to what others in the class were thinking or doing.

12. When I was asked to be creative, I often received positive feedback about my or my group’s approach.

~~

13. Learning in this class seemed more interesting and fun.

14. I think that this class encouraged me to be creative.

I

15. I believe that this class had the kind of environment that inspires youto be more creative.

played “devil’s advocate” and encour- aged students to challenge each other’s views.

12. Setting students up for success rather than failure. I regularly provided

positive feedback on individual or group discussions that showed an effort at cre- ativity, and I adopted a supportive style across course activities to boost students’ confidence in their creative abilites.

13. Requiring little if any rote learn- ing. Through various experiential learn- ing activities and assignments geared toward application and understanding of concepts rather than memorization, I

September/Octoher

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2001 31 [image:5.612.49.568.114.656.2]sought to make the learning experience more interesting and creative for stu- dents.

I also provided guidelines for the assignments, particularly the semester group projects, on how to make them more creative and indicated the weight- ing that creativity would receive in the overall project grade. Less than 5% of the actual grade depended on the cre- ativity of the presentation, as I sought to call student attention to it rather than

offer a real reward for it. In addition, throughout the course I encouraged students to view creativity as a learning tool and engage in it for their own ben- efit-to be internally motivated to exhibit it rather than feeling mandated to do so.

At the end of the semester, I had stu- dents fill out a survey measuring their perceptions of how various aspects of the classroom environment fostered cre-

ativity.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

An assistant collected the sur-veys from the students, so I did not have access to them until after the end of the semester, preventing students from feel- ing that their responses would have any impact on their class grade. The survey,

shown in Table 1 , consisted of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

15 ques-tions. Questions 1 through 13 related to each of the 13 dimensions presented earlier. Questions 14 through 15 assessed students’ overall perception of the classroom’s encouragement of cre- ativity. Students, whose responses

TABLE 2. Student Responses to 15 Survey Questions Regarding Classroom Creativity Dimensions

Response on scale T R S M O I Q A C F D P C E C C

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

M g t 4020

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( n =zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

17)Response5 (%) 29 24 41 35 53 53 53 29 59 24 18 29 35 47 53 Response4(%) 59 47 41 24 29 41 35 35 29 59 59 41 53 29 29 Response 3 (%) 6 18 6 18 12 0 12 24 6 12 12 6 12 24 18

Response 2 (%) 0 6 12 18 0 6 0 12 0 6 1 2 1 8 0 0 0

Response 1 (%) 6 6 0 6 6 0 0 0 6 0 0 6 0 0 0

Average response 4.06 3.76 4.12 3.65 4.24 4.41 4.41 3.82 4.35 4.00 3.82 3.71 4.24 4.24 4.35

Mdn 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 4 5 4 4 4 4 4 5

SD 0.97 1.09 0.99 1.32 1.09 0.80 0.71 1.01 1.06 0.79 0.88 1.26 0.66 0.83 0.79 M g t 3000 ( n = 28)

Response5 (%) 54 39 57 39 64 64 57 54 57 57 50 43 61 43 54 Response4(%) 36 29 39 39 36 29 32 29 32 39 29 36 29 39 36 Response 3 (%) 11 29 4 4 0 7 7 18 11 4 14 18 1 1 18 1 1

Response 2 (%) 0 4 0 1 8 0 0 4 0 0 0 7 4 0 0 0

Response 1 (%) 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Average response 4.43 4.04 4.54 4.00 4.64 4.57 4.43 4.36 4.46 4.54 4.21 4.18 4.50 4.25 4.43

Mdn 5 4 5 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 4 . 5 4 5 4 5

SD 0.69 0.92 0.58 1.09 0.49 0.63 0.79 0.78 0.69 0.58 0.96 0.86 0.69 0.75 0.69

Mgr 4010 ( n = 17)

Response5(%) 47 29 41 29 47 53 59 53 53 35 24 35 41 47 41 Response4(%) 35 41 47 24 47 35 24 24 41 35 41 53 24 18 29 Response 3 (%) 12 18 6 6 0 6 1 2 1 2 0 18 12 6 18 18 12

Response2(%) 0 12 6 3 5 0 0 0 6 0 12 18 0 12 12 12

Response 1 (%) 6 0 0 6 6 6 6 6 6 0 6 6 6 6 6

Averageresponse 4.18 3.88 4.24 3.35 4.29 4.29 4.29 4.12 4.35 3.94 3.59 4.12 3.82 3.88 3.88

Mdn 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 4 4

SD 1.07 0.99 0.83 1.41 0.99 1.05 1.10 1.22 1.00 1.03 1.23 0.99 1.29 1.32 1.27

M g t 4010-2 (n = 17)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Response5(%) 59 59 35 18 76 71 47 59 65 41 41 35 71 76 82 Response4(%) 35 29 65 59 18 18 41 35 24 53 35 59 24 12 12

Response 3 (%) 0 6 0 12 6 12 6 6 12 6 6 0 6 12 6

Response2 (%) 6 6 0 6 0 0 6 0 0 0 12 6 0 0 0

Response 1 (%) 0 0 0 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 0 0 0 0

Averageresponse 4.47 4.41 4.35 3.76 4.71 4.59 4.29 4.53 4.53 4.35 3.94 4.24 4.65 4.65 4.76

Mdn 5 5 4 4 5 5 4 5 5 4 4 4 5 5 5

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

SD 0.80 0.87 0.49 1.03 0.59 0.71 0.85 0.62 0.72 0.61 1.25 0.75 0.61 0.70 0.56

Nore. C =cooperation; 0 = other viewpoints: A = absence of judgment; F = free choice; R = reward; I = explore ideas; CC = creative classroom; D = diver-

sity: S = sensible risk: L = nonrote learning; Q = question assumptions: T = time; M = mistakes: P = positive feedback: E = encouraged to be creative.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

32 Journal of Education for Business

[image:6.612.48.566.216.706.2]remained anonymous, provided answers on a Likert-type scale ranging

from

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(strongly disagree) to 5 (strong-zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ly agree).

Findings

Results of the survey, shown in Table 2, indicate that the students in all four courses seemed to perceive their class- room environments as encouraging their creative behaviors. Both the response frequencies and the averages for all the particular dimensions of creativity, as well as the two more general measures (“encouraged to be creative” and “cre- ative classroom”) seem to indicate that students in all four courses agreed that the dimensions identified as critical for fostering creative behavior in the class- room were indeed present in their own classrooms. The averages, median scores, and relatively low standard devi- ations on all 15 responses demonstrate that most students either agreed or strongly agreed with the statements that indicated that creativity was fostered in various ways. Particularly encouraging were the high averages on responses to questions 14 and 15, which were designed to assess students’ overall per- ception of how their classroom encour- aged creativity.

Another noteworthy point about the survey results is that the perceptions of creativity seemed to be fairly stable across the four courses. The graph pro- vided in Figure 1, showing the average responses for each item across the four courses, demonstrates this stability.

The data in Figure

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 indicate that,though the subject matter varied in three of the four courses, with one course being taught across two sections and with class activities and exams

varying slightly, the overall instruc- tional method applied seems to have led to similar results. This in turn would indicate that creative behaviors can be stimulated in the classroom somewhat independently of a course’s specific theoretical content (of courses the courses in this study were still part of one discipline). Further, this may support the notion that the encourage- ment of creativity in the classroom is related more to the instructor’s meth- ods and approach than to the actual subject matter, and can become a part of a basic toolkit of instruction rather than being tied to a specific course or even program.

Conclusion

The integration of creativity into busi- ness education aids students in preparing for the creative workplace environments that are becoming more common as organizations seek to develop creative competencies as one of their few sus- tainable competitive advantages in today’s marketplace. My study of four business classrooms indicates that devel- oping the various characteristics identi- fied as stimulating creativity in the class- room does indeed encourage students to exhibit more creative behaviors.

This study, by presenting some of the

instructional techniques that can be used

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

tb foster the perception of a creative classroom environment, constitutes a first step toward the integration of cre- ativity into business education. It also lends support to the idea that business courses can support such instructional methods and that students do recognize them. The latter recognition, though cer- tainly not a proof that students actually

become more creative after experiencing such classroom environments, is a nec- essary condition for providing students with some education on creative think- ing in the business context. More research is needed to determine the exact value of exposing college students to creative classroom environments as a critical component of their preparation for their professional lives.

REFERENCES

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and

innovation in organizations, Resetrrch

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

In Orgtr-nizational Behavio4 10, 123-1 67.

Bernacki, E. (2000). Ckairi retrctive crerrtive. New Zealand Management, 47(2), 20-24.

Buchen, I. H. (2000). Paving the way for work- place creativity. National Productivitv Review:

19(2). 33-36.

De Souza Fleith, D. (2000). Teacher and student perceptions of creativity in the classroom envi- ronment. Roeper Review, 22(2), 148-158. Dess. G. G. (2000). Changing roles: Leadership in

the 21

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

st century. Organizational Dynamics,28(3), 18-34.

Eisenberger. R.. Fasolo, P., & Davis-LaMastro, V.

( 1 990). Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innova-

tion. Journul

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Applied Psychology, 7 3 I ) .51-59.

King Mildrum, N. (2000). Creativity workshops in the regular classroom. Roeper Review 22(3), 162-1 68.

Miller, M. (2000). Six elements of corporate cre- ativity. Credit Union Magazine, 66(4), 20-23.

Miller, W. C. (1987). The creative edge: Fostering innovation where vou work. New York: Addi- son-Wesley.

Nohria, N., & Gulati, R. (1996). Is slack good or bad for innovation? Academy of Management

Journal, 3Y(S), 1245-1264.

Palmer, G. A. (2000). Connected and alive with the arts. Converge, June, 60-66.

R0binson.A. G. & Stern, S. (1997). Corporate cre-

ativity: How innovation and improvement actw ally happen. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler. Siegel, S. M., & Kaemmerer. W. E (1978). Mea-

suring the perceived support for innovation in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology

Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. ( I 993). Toward a theory of organizational cre- ativity. Academy qf Management Review. 18(2), 63(5), 553-562.

293-32 I .