Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:09

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Learning Styles and Student Performance in

Introductory Economics

Bruce Brunton

To cite this article: Bruce Brunton (2015) Learning Styles and Student Performance in Introductory Economics, Journal of Education for Business, 90:2, 89-95, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.980716

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2014.980716

Published online: 12 Dec 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 245

View related articles

Learning Styles and Student Performance

in Introductory Economics

Bruce Brunton

James Madison University, Harrisonburg, Virginia, USA

Data from nine introductory microeconomics classes was used to test the effect of student learning style on academic performance. The Kolb Learning Style Inventory was used to assess individual student learning styles. The results indicate that student learning style has no significant effect on performance, undermining the claims of those who advocate greater instructional design concern for different learning styles.

Keywords: economics, learning models, learning preferences, learning style, teaching methodology

The notion that a student’s learning style is a crucial deter-minant of academic success has become increasingly popu-lar in recent years. The groundswell for support for this notion is strong in both the core Education literature and in the peripheral educational literature of the physical scien-ces, social scienscien-ces, and business disciplines. Reasons for the rising popularity of learning styles may be coming from two directions. As Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, and Bjork (2009) suggested, there is a booming learning style industry selling questionnaire sets, guidebooks, evaluation software, and consulting services. In addition to this push factor is a growing chorus of voices among the higher education user community arguing that the quality of college education is declining while tuition costs continue to rise. Arum and Roksa’sAcademically Adrift(2011), for example, revealed three trends: average grades are up, student time preparing for class is down, and measured learning gains are down, relative to several decades ago. The claim spawned by their survey that 45% of students did not show any significant improvement in learning during their first two years of col-lege is a bullet point that is difficult to ignore. Their results were uneven across majors and schools but one of the gen-eral trends noted was that students majoring in business were among the majors that had the smallest gains in criti-cal thinking. Given this troubling scenario, any effort that claims to improve learning outcomes (e.g., greater class-room focus on learning style issues) warrants more

attention. The purpose of this paper is to provide some addi-tional empirical evidence on learning styles and evaluate the implications for business faculty.

The article is organized as follows. In the next section the general literature on learning styles and the associated empirical research on student learning style and academic success is briefly reviewed. Then an overview of the Kolb learning model is presented. This is followed by a descrip-tion of the data, discussion of the course design used, and a summary and interpretation of the statistical results. In the concluding section I suggest a general strategy for business faculty to address student learning style issues.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

There are dozens of models of learning styles and it is beyond the scope of this paper to review and assess the entire field (for a thorough review of learning style models, see Cassidy, 2004). Learning style models based on the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; Coffield, Moseley, Hall, & Ecclestone, 2004) personality measures were the first to achieve broad usage. These models are rooted in Carl Jung’s writings on personality archetypes. Perhaps because of this origin, personality type and learning style are often considered semantically equivalent. The MBTI approach is based on how a person identifies along four dichotomies: life orientation (extravert vs. introvert), per-ception (sensing vs. intuitive), mode of decision making (thinking vs. feeling), and attitude (judging vs. perceiving). Respondents’ results lead to a designation of one of 16 dif-ferent psychological types. A number of related models

Correspondence should be addressed to Bruce Brunton, James Madison University, Department of Economics, 800 S. Main Street, MSC 0204, Harrisonburg, VA 22812, USA. E-mail: bruntobg@jmu.edu

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.980716

have emerged that are variations of the 16-type MBTI, allowing designers to modify questionnaires or extend sur-veys to achieve a better field match.

Another widely used model is Kolb’s Learning Style Inventory (LS; Kolb, 1976) which similar to the MBTI has been extended and modified by later researchers. Kolb (1984) argued that “knowledge results from the combina-tion of grasping and transforming experience” (p. 41). Kolb’s early work (Kolb, 1971, 1981) on experiential learn-ing theory lead him to draw attention to conflicts between student learning styles and the styles common among dif-ferent disciplines. This framing of learning theory in terms of discipline specific insights and the convenience of a short survey have made Kolb’s model popular and Kolb’s own home base in management might have added to the appeal of his LSI as an instrument for business education research.

Kolb (1981) mapped out the position of different disciplines in his learning style grid. A number of studies have since tried to verify the disciplinary learning styles indicated by Kolb and explain others he had not mentioned. Robert Loo (2002), in this journal, provided the most comprehensive review of stud-ies that have typed the learning styles of business majors. Beyond trying to establish which learning styles are most com-mon, other writers (e.g., Goortha & Mohan, 2010) have offered curriculum design suggestions based on recognizing which learning styles are most prevalent.

More ambitious efforts have sought to empirically deter-mine whether learning styles affect academic performance. While the results are mixed they appear to lean toward a consensus that learning styles matter. There have been a number of studies in economics that support the consensus view (e.g., Boatman, Courtney, & Lee, 2008; Borg & Shapiro, 1998; Borg & Stranahan, 2002; Emerson & Taylor, 2007; Ziegart, 2000). Several of the economics edu-cation studies have tended to also support a related result that a match between the learning style of student and teacher improves student performance, although as Borg and Stranahan pointed out, this affect disappears in upper level courses. Fallen (2006) found significant differences in student learning styles and performance among business majors in Norway, suggesting the learning style–academic performance link is not related to national borders.

Bacon (2004) represents the minority opinion, finding that learning styles had little effect on learning outcomes for marketing students. While there are fewer dissenting voices, as Pashler et al. (2009) suggest, the rapid expansion of the learning style industry in recent years ought to prompt some healthy skepticism. Further, Pashler et al. and other recent voices from psychology have offered a serious twofold critique: first, that surveying students about prefer-ences is not the same thing as empirically determining learning styles and, second, as Rohrer (2012) noted, “even if the empirical evidence revealed a consistent benefit of style-based instruction, providing tailored instruction would not make sense unless its benefits were large” (p 65), and

the high costs of such instruction are typically ignored in this debate.

KOLB’S LEARNING THEORY AND LEARNING STYLES

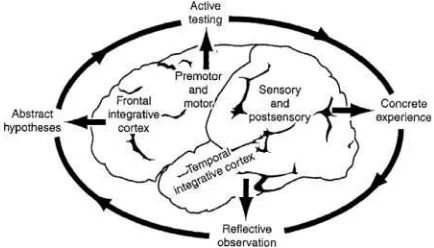

Kolb (1971, 1981) posed a dichotomy for grasping experi-ence between concrete experiexperi-ence (CE) and abstract conceptualization (AC) and a dichotomy in modes of trans-forming experience between reflective observation (RO) and active experimentation (AE). He contended that the experiential learning process being described relates to the process of brain functioning as depicted in Figure 1. The responses to a set of 12 questions in the LSI lead to scores for these four dimensions, which in turn allow for a deter-mination that one of four learning styles is dominant.

Kolb (1984) suggested that students develop a prefer-ence for learning in a particular way. Students may adopt different learning styles in different situations, but they tend to favor some learning behaviors over others. He iden-tifies four learning styles:

Divergersview situations from many perspectives and

rely heavily on brainstorming and generation of ideas.

Assimilators use inductive reasoning and have the

ability to create theoretical models.

Convergers rely heavily on hypothetical–deductive

reasoning.

Accommodatorscarry out plans and experiments and

adapt to immediate circumstances.

Each of the learning styles is associated with a different way of solving problems, as indicated in Figure 2. The par-ticular choice of learning style reflects the individual’s abil-ities, environment, and learning history. According to Kolb (1984), individuals learn better when subject matter is pre-sented in a way that is consistent with their preferred learn-ing style. Kolb and others uslearn-ing his model (e.g., Nulty & Barrett, 1996) have proposed possible disciplinary matches to the four leaning styles, as suggested in Figure 3.

FIGURE 1 The experiential learning cycle and regions of the cerebral cortex (reproduced from Kolb & Kolb, 2005).

90 B. BRUNTON

There is a seductive logic that emerges from this litera-ture—because learning styles are apparently easy to iden-tify, and vary by major, faculty can presumably optimize student performance by choosing an instructional design that matches learning style to major. However, several cav-eats should be noted. First, it is too easy to assert a major uniformly has a particular learning style. As Kolb (1984) noted, “undergraduate majors are described only in the

most gross terms. There are many forms of engineering or psychology. A business major at one school can be quite different from one at another” (p. 86). Second, a learning style is not equivalent to a genetic marker that a person will have for life. Kolb (1984) contended that the four learning modes (CE, AC, RE, and AE) he identified are parts of a learning cycle that all individuals experience. Which modes a person emphasizes change over time with changing work FIGURE 2 Characteristics of Kolb’s learning styles. AED active experimentation; ROD reflective observation; AC Dabstract conceptualization;

CEDconcrete experience.Source: Adapted from Kolb (1984).

FIGURE 3 Learning styles and disciplinary groups.Source: Nulty and Barrett (1996).

and life experiences and greater educational attainment. From this perspective, the ideal instruction mix would be the one that optimally moves each student along his or her learning styles evolutionary path. Obviously, such individ-ual tailoring of teaching is not possible. Finally, from the experiential learning theory perspective A. Y. Kolb and D. A. Kolb (2005) advocated, learning is a holistic, adaptive process. Because optimal learning would involve progres-sively more successful integration of the four learning modes, the more logical instructional focus is the entire degree curriculum rather than a single course.

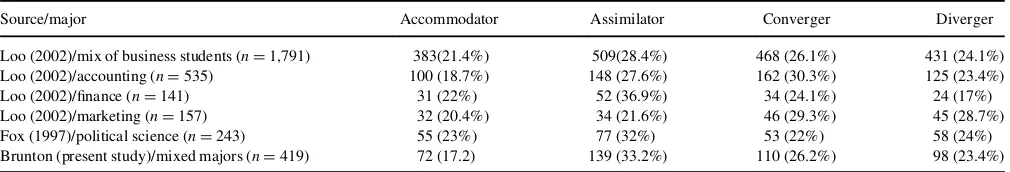

In Table 1 the distribution of learning styles is shown for different groups of undergraduates. Loo’s (2002) metastudy reveals several patterns. A large undergraduate pool of business students with diverse majors produces a relatively even allocation across the four learning styles. The distribu-tion of political science majors is similar to business majors and both groups have a slight tilt toward the assimilator style. Fox and Ronkowski (1997) found the share of assimi-lators rises with upper compared to lower class students. The difference in percentages of divergers and assimilators between finance and marketing majors suggests that instructional design influenced by expected learning style distributions is more plausible for upper division courses.

METHODS, DATA, AND RESULTS

Using Kolb’s (1976) four learning styles as dummy varia-bles, performance differences were estimated and the results are presented in this section. The sample used included 419 undergraduates who took introductory microeconomics (and completed the course and provided complete information for all variables included in the sample) in one of the nine sections taught over a three-semester period. In each of these nine classes, students had the same textbook, course design, and instructor. This comparability across classes is an advantage for pooling data. Often in other studies, to get a big enough sample size, multiple instructors are included and this creates the problem that instructor effects are a source of variance in student performance results.

The student population taking introductory microeco-nomics is primarily freshmen and sophomores and primar-ily business majors but there are also a variety of other

majors. The male–female ratio for the sample was roughly 60–40 and the distribution of student learning styles for these two groups was similar, as indicated in Table 2. The teaching method used in each section was a combination of lecture and small group cooperative activities. Classes met three days a week and two of those days involved tradi-tional lecture. The third day was used for small-group proj-ects, quizzes, assignments, or activities related to the material covered in the preceding two classes. Groups were composed of 4–5 students, selected so that group composi-tion achieved a gender balance and a diversity of learning styles, pretest scores, and students who had previously (and not previously) taken an economics course. Most group work was done in class.

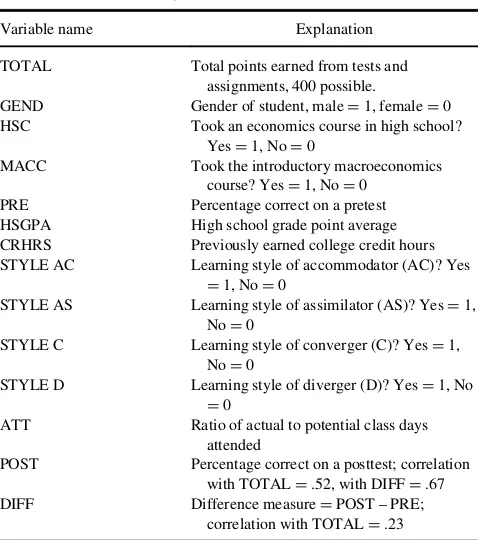

The estimation process added student learning style as a mediating, additional input to a set of independent variables that reflect the human capital students bring to a course. This educational production function approach is fairly conventional in business education research. Student per-formance was assumed to be affected by their innate ability (captured by grade point average [GPA], SAT score, or ACT score), whether they had previously taken other eco-nomics courses or were familiar with the subject matter, general student skills inferred from total credit hours taken in college, and their effort, which was proxied by atten-dance. Information on these variables is presented in Table 3.

Student performance can be measured in several ways: the total points generated over the semester from tests and assignments, the performance on an end of semester TABLE 1

Learning Styles Distribution of College Students

Source/major Accommodator Assimilator Converger Diverger Loo (2002)/mix of business students (nD1,791) 383(21.4%) 509(28.4%) 468 (26.1%) 431 (24.1%)

Loo (2002)/accounting (nD535) 100 (18.7%) 148 (27.6%) 162 (30.3%) 125 (23.4%)

Loo (2002)/finance (nD141) 31 (22%) 52 (36.9%) 34 (24.1%) 24 (17%)

Loo (2002)/marketing (nD157) 32 (20.4%) 34 (21.6%) 46 (29.3%) 45 (28.7%)

Fox (1997)/political science (nD243) 55 (23%) 77 (32%) 53 (22%) 58 (24%)

Brunton (present study)/mixed majors (nD419) 72 (17.2) 139 (33.2%) 110 (26.2%) 98 (23.4%)

TABLE 2

Distribution of Students, by Learning Style and Gender

Category Accommodator Assimilator Converger Diverger All students

nD419 nD72 nD139 nD110 nD98

100% 17.2% 33.2% 26.2% 23.4% Male students

posttest, and/or the difference in posttest score versus pretest score. A pretest was given on the first day of class and a posttest that had 75% of the pretest questions was embedded in the final exam. Because of this approach, pretest and posttest variables are percentages rather than raw scores. As indicated in Table 3, the three perfor-mance measures are not highly correlated. Although the somewhat low correlation between TOTAL and POST is somewhat puzzling, the more important issue is whether the relationship between learning styles and performance is different for the various dependent variable possibili-ties. The similar performance across learning styles for TOTAL, POST, and DIFF can be seen in the sample means data in Table 4. TOTAL is the preferable depen-dent variable because it reflects a fuller spectrum of stu-dent work and it is used for the ordinary least squares regression estimates shown in Table 5.

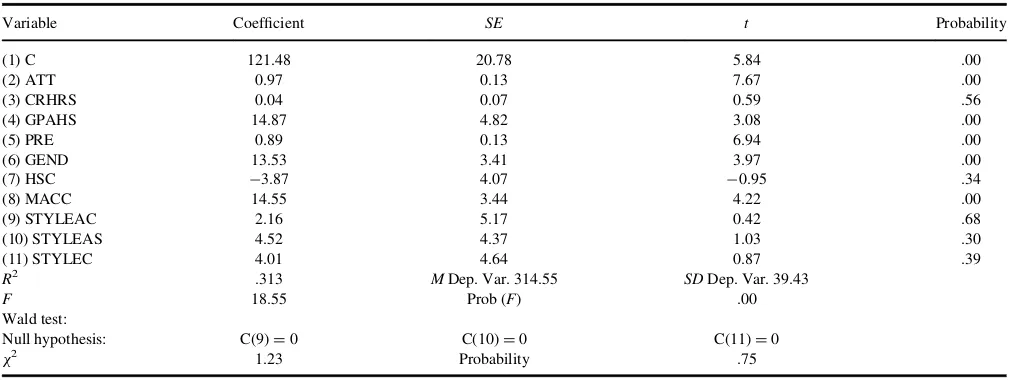

Several of the results in Table 5 are consistent with pre-vious education research. Attendance (ATT), as prepre-viously demonstrated (e.g., Romer [1993] is the classic), does mat-ter. As ATT is measured in percentage terms, the 0.97 regression coefficient means a one-unit (1%) increase in attendance results in an almost one-point increase in total points. With a maximum possible total of 400 points in a semester, a student attending 90% of the classes is likely to earn a full letter grade higher than a student who attends 50% of the classes. Positive and significant relationships also are evident for ability and previous awareness of the subject. High school GPA may not be the best proxy for

innate ability but it is easier to obtain than college GPA (freshmen may have none when they take the course) or SAT scores. A 1.3-point increase in GPA is worth about 20 points, or half a letter grade. Similarly, having taken the introductory macroeconomics course (MACC) before tak-ing the microeconomics course is worth about one third of a letter grade. The pretest score (PRE) captures some of the previous course work effect of the MACC variable; it is also, as expected, highly significant. Another familiar result in economics is the differential gender performance (for explanations, see Walstad, 1995). Being a male is worth about one third of a latter grade in the results here.

The number of previous credit hours was included to capture student skills. Students who have taken more courses should have a better sense of how to study and man-age their time. However, this assumed human capital mea-sure is only slightly positive and not significant. Having taken an economics course in high school (HSC) has a neg-ative sign, perhaps suggesting some type of offsetting behavior; however, the result is not significant.

Given the studies in economics and other fields cited ear-lier that claim learning style affects performance and the LSI disciplinary grouping match of economics majors as assimilators, it would be reasonable to expect that the Assimilator dummy variable would turn out to be positive and significant. The results in Table 5 indicate positive coefficients for the accommodator (AC), assimilator (AS), and converger (C) learning styles relative to the diverger (D) style. As with all dummy variables, this means there is an upward shift of the intercept of the regression line when the performance of students with either the AC, AS, or C learning styles is compared to the baseline style D. Although the coefficient of the AS variable is slightly more positive than the AC or C styles, it is not statistically signif-icant at any normally accepted level. Moreover, the learn-ing style variables are neither individually significant nor jointly significant.

The results of a Wald test for joint significance are shown in Table 5. The Wald test operates by testing the null hypothesis that a set of independent variables is equal to some value. In the model tested here, the null hypothesis is that the coefficients of the three learning style variables TABLE 3

Explanation of Variables

Variable name Explanation TOTAL Total points earned from tests and

assignments, 400 possible.

GEND Gender of student, maleD1, femaleD0

HSC Took an economics course in high school? YesD1, NoD0

MACC Took the introductory macroeconomics course? YesD1, NoD0

PRE Percentage correct on a pretest HSGPA High school grade point average CRHRS Previously earned college credit hours STYLE AC Learning style of accommodator (AC)? Yes

D1, NoD0

STYLE AS Learning style of assimilator (AS)? YesD1,

NoD0

STYLE C Learning style of converger (C)? YesD1,

NoD0

STYLE D Learning style of diverger (D)? YesD1, No D0

ATT Ratio of actual to potential class days attended

POST Percentage correct on a posttest; correlation with TOTALD.52, with DIFFD.67

DIFF Difference measureDPOST – PRE;

correlation with TOTALD.23

TABLE 4

Sample Means of Key Variables for the Four Learning Styles

Variable AC (nD72) AS (nD139) C (nD110) D (nD98) Average

TOTAL 308.13 317.21 317.99 312.01 314.63 POST 61.94 62.35 63.67 62.49 62.66 DIFF 28.32 26.02 27.07 26.45 26.79 PRE 33.63 36.33 36.6 36.04 35.87 HSGPA 3.62 3.68 3.72 3.66 3.68 CRHRS 29.32 31.72 34.23 29.71 31.49 ATT 86.64 88.53 90.08 89.12 88.75

Note: AC D accommodator; AS D assimilator; C D converger;

DDdiverger.

(listed as variables 9, 10, and 11 in Table 5) are simulta-neously equal to zero, as shown in Table 5 by the specific variable constraints of C(9) D0 C(10)D0 C(11)D0. If the test fails to reject the null hypothesis, this suggests that dropping the variables from the model will not have an adverse effect on the fit of the model,x2D1.23,pD.75. If thep value were less than the commonly used criterion of .05, the null hypothesis would be rejected; because it is not, the null hypothesis that the coefficients are simultaneously equal to zero can be accepted.

CONCLUSION

This study indicates that learning style differences are not significant determinants of performance in introductory microeconomics. It would be a mistake, however, to con-clude that learning styles do not matter. Rather, the more appropriate general conclusion is that we do not yet know enough about learning styles. Pashler et al.’s (2009) cri-tique that the research so far is not correctly testing perfor-mance differences in learning styles needs to be addressed. But even if this critique were unwarranted, Kolb himself (1984) pointed out that learning styles evolve and that sim-ple discipline designations are inappropriate. Static labels are convenient but perhaps misleading. Freshmen and soph-omore undergraduates, the relevant group for this study, are still in a formative stage. If there is more fluidity in learning styles at this stage in their development, it would make sense that learning style variables would not be useful pre-dictors. Following this logic, only when students have taken enough courses in a particular field will their learning style begin to adapt to the disciplinary characteristics of their major. Therefore, learning style concerns for faculty may

be more relevant in upper division undergraduate and grad-uate courses.

For lower level undergraduate courses, the more relevant lesson of this study is that attendance matters. Rather than try to identify learning styles and target different styles with matching techniques, faculty should simply concen-trate on creating an engaging classroom to encourage higher attendance. This is of course a perennial pedagogical goal that involves designing a course employing some diversity of teaching methods so that students have a vari-ety of stimuli.

REFERENCES

Arum, R., & Roksa, J. (2011).Academically adrift: Limited learning on college campuses.Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Bacon, D. R. (2004). An examination of two learning style measures and their association with business learning.Journal of Education for Busi-ness,79, 205–208.

Boatman, K., Courtney, D., & Lee, W. (2008). See how they learn: The impact of faculty learning styles on student performance in introductory economics.American Economist,52, 39–48.

Borg, M. O., & Shapiro, S. L. (1996). Personality type and student perfor-mance in principles of economics.The Journal of Economic Education,

27, 3–25.

Borg, M. O., & Stranahan, H. A. (2002). Personality type and student per-formance in upper- level economics courses: The importance of race and gender.The Journal of Economic Education,33, 3–14.

Cassidy, S. (2004). Learning styles: An overview of theories, models, and measures.Educational Psychology,24, 419–444.

Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E.. & Ecclestone, K. (2004).Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review.London, UK: Learning and Skills Network.

Emerson, T. L., & Taylor, B. A. (2007). Interactions between personality type and the experimental methods.The Journal of Economic Educa-tion,38, 18–35.

Fallan, L. (2006). Quality reform: Personality type, preferred learning style and majors in a business school.Quality in Higher Education,12, 193–206.

TABLE 5

Regression Results With Total Points Earned as Dependent Variable (nD419)

Variable Coefficient SE t Probability

(1) C 121.48 20.78 5.84 .00

(2) ATT 0.97 0.13 7.67 .00

(3) CRHRS 0.04 0.07 0.59 .56

(4) GPAHS 14.87 4.82 3.08 .00

(5) PRE 0.89 0.13 6.94 .00

(6) GEND 13.53 3.41 3.97 .00

(7) HSC ¡3.87 4.07 ¡0.95 .34

(8) MACC 14.55 3.44 4.22 .00

(9) STYLEAC 2.16 5.17 0.42 .68

(10) STYLEAS 4.52 4.37 1.03 .30

(11) STYLEC 4.01 4.64 0.87 .39

R2 .313 MDep. Var. 314.55 SDDep. Var. 39.43

F 18.55 Prob (F) .00

Wald test:

Null hypothesis: C(9)D0 C(10)D0 C(11)D0

x2 1.23 Probability .75

94 B. BRUNTON

Fox, R. L., & Ronkowski, S. A. (1997). Learning styles of political science students.PS: Political Science and Politics,30, 732–737.

Gootha, P., & Mohan, V. (2010). Understanding learning preferences in the business school curriculum.Journal of Education for Business,85, 145–152.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education.Academy of Man-agement Learning and Education,4, 183–212.

Kolb, D. A. (1971).Individual learning styles and the learning process. Working Paper #535-71. Cambridge, MA: Sloan School of Manage-ment, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Kolb, D. A. (1976).The Learning Styles Inventory: Technical manual.

Boston, MA: McBer & Company.

Kolb, D. A. (1981). Learning styles and disciplinary differences. In A. Chickering (Ed.),The modern American college (pp. 232–255). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kolb, D. A. (1984).Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development.Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Loo, R. (2002). A meta-analytic examination of Kolb’s learning style pref-erences among business majors.Journal of Education for Business,77, 252–256.

Nulty, D. D., & Barrett, M. A. (1996). Transitions in students’ learning styles.Studies in Higher Education,21, 333–345.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2009). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest,9, 105–119.

Rohrer, D., & Pashler, H. (2012). Learning styles: Where’s the evidence?

Medical Education,46, 634–635.

Romer, D. (1993). Do students go to class? Should they?Journal of Eco-nomic Perspectives,7, 167–174.

Walstad, W. B., & Robson, D. (1997). Differential item-functioning and male-female differences on multiple-choice tests in economics. The Journal of Economic Education,28, 155–171.

Ziegert, A. L. (2000). The role of personality temperament and student learning in principles of economics: Further evidence.Journal of Eco-nomic Education,31, 307–322.