Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 19:18

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Indonesian politics in 2011: democratic regression

and Yudhoyono's regal incumbency

Greg Fealy

To cite this article: Greg Fealy (2011) Indonesian politics in 2011: democratic regression and Yudhoyono's regal incumbency, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 47:3, 333-353, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2011.619050

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2011.619050

Published online: 16 Nov 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1259

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/11/030333-21 © 2011 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2011.619050

INDO NESIAN POLITICS IN 2011: DEMOCRATIC REGRESSION AND YUDHOYONO’S REGAL INCUMBENCY

Greg Fealy*

Australian National University

In 2011, a number of trends in Indonesian politics became clearer. President Susi -lo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) has not become a more reformist and risk-taking president in his second term, contrary to the hopes of many, but has rather become more cautious, aloof and regal in style. He is irked by criticism and dislikes any disturbance to the authority of his rule. The political elite, often in concert with the SBY government, pushed through a range of democratically regressive measures, including allowing politicians to be appointed to the Elections Commission. The malaise within the party system deepened, with less than a quarter of the electorate

professing any party afiliation. Most Islamic parties slid closer to the political peri-phery, and the largest one, PKS, was beset by controversy. Government and com -munity responses to a brutal attack on the Ahmadiyah sect in early 2011 showed the

limits of Indonesia’s much lauded religious tolerance.

Keywords: democratic regression; political Islam; religious intolerance; corruption; pres-idential incumbency

Indo nesia is now in the third year of its quinquennial electoral cycle. The new parliament was installed in August 2009 and President Susilo Bambang Yudho-yono (SBY) began his second term the following month. This is a good juncture at which to assess political trends for the ive-year period, as the legislature, parties and government have settled into patterns of behaviour that will probably prevail till at least the 2014 elections, if not beyond. Of late, Indo nesia and SBY have been basking in the praise of Western political leaders and often, also, the international media. Indo nesia is lauded as a success story of democratisation, religious toler -ance and stability in a Muslim-majority nation. It is held up as a beacon both to the broader Islamic world, where authoritarianism and sectarian conlict are common, and to other Southeast Asian nations, which tend to be rated as only

* This is a revised version of a paper presented to the 29th Indo nesia Update conference,

held at the Australian National University, Canberra, on 30 September 2011. The author

would like to thank Ed Aspinall, Marcus Mietzner and Ken Ward for valuable comments

on an earlier draft. Douglas Ramage, the Managing Director of BowerGroupAsia’s Indo-nesia ofice, acted as discussant of the paper presented at the conference; some of his com -ments are appended in box 1 at the end of this paper.

334 Greg Fealy

semi-democratic or undemocratic.1 SBY is cast as a statesman and reformist

presi-dent whose own values of decency and moderation have imparted greater civility to Indo nesian politics.

The picture I will paint of Indo nesia and its president is less lattering, though by no means bleak. The political system has for several years shown signs of democratic stagnation and backsliding, a trend examined by a number of schol-ars, most notably Marcus Mietzner.2 But during 2011, the evidence that political

reforms are being rolled back became much stronger. On the one hand, the politi-cal elite is tightening its grip on key oversight institutions, often in a manner that reduces transparency as well as the public standing and effectiveness of those institutions. This has the effect of weakening the checks and balances for the exer-cise of power. On the other hand, the parliamentary and party systems, in which much of the elite is embedded, are themselves beset by a deepening malaise that harms their competence and may, over time, undermine conidence in democracy. Far from being a reformist president, SBY is increasingly conservative, remote from his cabinet, governed by public opinion and consumed with his own stand-ing and legacy. Moreover, he is as likely as not to tacitly sanction democratically regressive proposals, even if he does not initiate them. At the same time, Indo-nesia’s record on religious tolerance is being tarnished by sectarian violence, with both the state and civil society complicit in the intimidation and victimisation of unpopular minorities. SBY and his government have contributed to this decline in religious rights, albeit unintentionally. A pithy summation of my argument might be: ‘Indo nesia: not as good as it seems’.

SBY’S REGAL PRESIDENCY3

At the beginning of SBY’s second term, some commentators predicted that we would see a different president from the vacillating, often politically timid ig -ure of the preceding ive years. According to this view, SBY, freed of the burden of re-election, would pursue bold policies in order to cement his place in Indo-nesian history as a visionary president committed to change. In fact, the opposite has been the case. SBY appears to be less concerned with economic and political reform now than he was in his irst term. Instead, he appears preoccupied with status and incumbency. The president seems increasingly not so much to rule as to reign over the country, and he desires to do so serenely. He is acutely sensitive to criticism and to any breaches of protocol that might be taken as disrespectful. Every morning, he and his wife, Ani, are said to pore over the newspapers at breakfast, paying particular attention to critical coverage of the palace or the gov-ernment. Personal attacks on SBY in the media will often agitate him for hours, if not days. He is especially perturbed by controversies that force him into the politi-cal fray to defend himself or his ministers, or to take swift action; when he appears

1 See, for example, Freedom House’s global democracy rankings, which classify Indo nesia as the only full democracy in Southeast Asia. The 2011 rankings are available at <http:// www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=594>.

2 See Mietzner (2011); see also EIU (2008).

3 Much of the material for this section is drawn from conidential interviews with senior oficials and politicians in Jakarta conducted during the irst half of 2011.

in public he seeks to convey a calm, self-possessed authority. In this sense, he aspires to be a regal president.

The style of SBY’s leadership of government has also changed during this term, and not for the better. The president is increasingly aloof from most of his min-isters and relies ever more heavily on a small circle of trusted advisers, notably Hatta Rajasa, the Coordinating Minister for the Economy, Djoko Suyanto, the Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs, and Sudi Silalahi, the State Secretary and a long-time SBY lieutenant. Substantive discussion of pol-icy issues rarely occurs in cabinet and SBY appears to regard such meetings as an opportunity to deliver lengthy, often leaden, disquisitions on problems facing the nation or government. So common has his lecturing become that some ministers have ruefully nicknamed him ‘The Professor’. Many ministers have never been granted a face-to-face meeting with the president, and even senior ministers com-municate with SBY primarily through Hatta, Djoko or Sudi, or cabinet secretary Dipo Alam. A number of more resourceful ministers, frustrated with their lack of direct access and presidential inertia, have persuaded colleagues or sympathetic journalists to write prominent articles in newspapers such as Kompas or Jawa Pos in order to gain SBY’s attention and sway him to act on an issue.

Despite his growing detachment, the president remains, as ever, hesitant in his decision making. One popular joke in Jakarta claims that when asked to choose between ‘A’ or ‘B’, SBY chooses ‘or’! He is especially susceptible to lobbying by important igures, and has been known – much to the chagrin of his ministers – to zig-zag on issues as he comes under pressure from competing forces.

Although SBY’s cautious and increasingly courtly approach to politics does not lead to daring or innovative decision making, it has nonetheless produced settled and stable conditions that are conducive to rapid economic growth. By instinct and personality, SBY is a politician of the ‘middle’. Whenever possible he seeks to avoid conlict with major political or economic forces and tries not to push against the tide of public opinion. Before making important decisions, he or his staff will take soundings from powerful stakeholders in an effort to calculate the political risks. While this is not unusual behaviour for a politician, SBY will often stall or prevaricate on key decisions for weeks or months in a manner contrary to the image of managerial eficiency that he seeks to cultivate. He is particularly heedful of community attitudes and he studies public opinion surveys intently to ensure that, where possible, he is in step with popular sentiment. On many con-tentious issues, SBY has been prepared to decide a matter only after seeing polling data and has chosen a course of action exactly in accord with the majority view. While this pattern of behaviour allows him to defuse potentially divisive issues, it also means that he seldom leads or shapes public opinion and is reluctant to debate controversial initiatives. The removal of fuel subsidies was one such pol-icy issue. While SBY accepted the need to reduce subsidies, he was unwilling to announce the decision himself because of its likely unpopularity. Instead, he left it to his economic ministers to announce and defend the policy.

A further problem is that SBY’s second cabinet has proven to be much weaker than its predecessor. In his irst cabinet, SBY had ‘can-do’ igures such as Vice President Jusuf Kalla and the Coordinating Minister for People’s Welfare, Aburizal Bakrie, to drive through policies and legislation and to respond to thorny issues. There is no comparable igure in the present government. Vice President

336 Greg Fealy

Boediono has great integrity and technical expertise but he has little political nous or clout. Hatta is a savvy strategist and deal maker with broad political connec-tions but he cannot command the vast inancial resources of Bakrie when seeking to ‘persuade’ parliamentarians to pass important bills. Also, the number of under-performing ministers is much greater than in the preceding government, a situa-tion that relects the president’s own prioritising of political stability and loyalty over merit and initiative. The relative weakness of cabinet has been highlighted by the regular ‘report cards’ on ministerial performance issued by the Presidential Working Unit for Supervision and Management of Development (Unit Kerja Pres -iden bidang Pengawasan dan Pengendalian Pembangunan, or UKP4).4

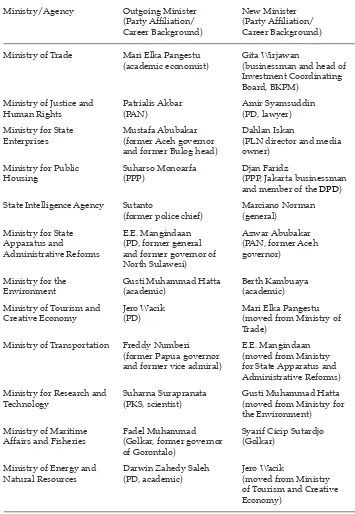

Given the mounting criticism of the government, SBY reshufled his cabinet in late October. The reshufle was more extensive than predicted: 12 ministries changed hands, with eight ministers dismissed and four shifted to new portfolios (table 1). In addition, some 10 new deputy ministers were appointed. In many ways, the new line-up relected the same compromise between technocratic merit and political expediency that had marked SBY’s earlier decisions on cabinet com-position. While the removal of Mari Pangestu as trade minister was unexpected given that she was regarded as one of the more competent cabinet members (Manning and Purnagunawan 2011: 322, in this issue), the appointment of Gita Wirjawan as her replacement won plaudits from many commentators. The reten-tion of Minister of Finance Agus Martowardojo, who had stood irm against pres -sure from powerful political and business interests, was a victory for Boediono and other economic technocrats in the government.

The most controversial aspects of the reshufle were the failure to remove two ministers embroiled in corruption scandals, the Minister for Manpower and Trans-migration, Muhaimin Iskandar, and the Minister for Youth and Sports Affairs, Andi Mallarangeng; and the appointment of SBY loyalists in the president’s Dem-ocrat Party (Partai Demokrat, or PD) to strategic portfolios such as energy and transportation. The appointments of Jero Wacik to the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources and of E.E. Mangindaan to the Ministry of Transportation were widely criticised given that the new ministers had no relevant expertise. The deci-sion appeared to relect PD’s determination to secure greater funding for the 2014 elections from money-rich ministries.5

DEMOCRATIC REGRESSION

For several years, political observers have been warning of the risk of reversal of Indo nesia’s democratisation process (Aspinall 2010; Haris 2011; Mietzner 2011). Mietzner, for example, has argued strongly that most of Indo nesia’s signiicant reforms took place before 2006, with stagnation and some roll-back of democ -racy evident since then. Indications of this regressive trend became far more pronounced during 2011, with the four most salient forms being: the deliberate undermining of key oversight institutions whose primary purpose is to ensure the transparency and integrity of political, economic and bureaucratic processes;

4 ‘UKP4: ministries with “red marks” evenly distributed’, Indo nesia Today, 28/9/2011.

5 ‘SBY controls “lucrative” posts’, Jakarta Post, 19/10/2011.

TABLE 1 Cabinet Changes Announced in October 2011a

Ministry of Trade Mari Elka Pangestu (academic economist)

Ministry of Transportation Freddy Numberi (former Papua governor

a PLN: Perusahaan Listrik Negara (the state electricity company); DPD: Dewan Perwakilan Daerah (Regional Representatives Council); see text and footnote 12 for an explanation of other abbreviations.

338 Greg Fealy

the winding back of regional elections and local democracy; the deepening prob-lems in the functioning of parties and the legislature; and the failure to protect minority rights (discussed in the inal section of this article).

In many instances the government and the major political parties act in con -cert to initiate regressive measures, with both sharing a common interest either in lessening scrutiny of their actions, particularly the risk of malfeasance being exposed, or in expanding their inluence over political processes. The institu -tions most commonly targeted by the political elite are the Corruption Eradica-tion Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, or KPK) and the ElecEradica-tions Commission (Komisi Pemilihan Umum, or KPU), but other bodies such as the Supreme Audit Agency (Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan, or BPK) and the Judicial Commission (Komisi Yudisial) have not been immune.

Together with the Constitutional Court, the KPK has been the most successful new institution of the post-Soeharto era. Since its establishment in 2003, the KPK has investigated more than a thousand corruption cases, many of them involv-ing ministers, governors, mayors, parliamentarians, senior bureaucrats and other prominent igures. In mid-2011, the Minister for Home Affairs informed parlia -ment that the KPK was investigating 155 regional govern-ment heads, including 17 governors. Over the past six years more than two dozen parliamentarians have been found guilty of graft and gaoled. Although the KPK’s public approval rating has slipped from 58% to 41% over the past year, it remains one of the more trusted institutions.6

The KPK’s success in uncovering corruption and bringing high-proile politi -cians and oficials to justice has earned it the wrath of many in elite circles. The parliament has repeatedly sought to curtail the Commission’s investigative and prosecutorial powers, and to appoint less credible or more compliant commis-sioners. For the most part, pressure from the KPK, civil society groups and the media has forced parliament to refrain from making sweeping changes to the KPK’s powers, but attacks on the Commission continue (Butt 2011, in this issue). Fahri Hamzah, a senior parliamentarian from the Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera, or PKS), recently called for the KPK’s disbandment, claim-ing that it was actclaim-ing undemocratically.7 A parliamentary committee is currently

vetting a short-list of nominees for the KPK leadership, with a view to making a recommendation to the president on the inal composition of the Commission (Schütte 2011, in this issue).

The composition and reporting requirements of the Elections Commission, the KPU, have also been the subject of heated debate between political parties on the one hand and NGOs and commentators on the other. In 2011, the major parties pushed through legislation that allowed politicians to serve on the KPU board, provided they irst resigned from their parties. The politicians argued that par -ties were legitimate stakeholders in the electoral system and should therefore be represented on the KPU board. They also pointed to the poor performance of the outgoing board, which was composed largely of ex-bureaucrats and academics with technocratic backgrounds. Undoubtedly many parties were keen to expand

6 ‘Empat alasan kepercayaan public menurun terhadap KPU [Four reasons for falling public trust in KPU]’, Media Indo nesia, 7/8/2011.

7 ‘House corners KPK, threatens its dismissal’, Jakarta Post, 4/10/2011.

their inluence within the KPU so that decisions on the conduct of the 2014 elec -tions could be manipulated to favour their interests.

The new law also obliged the KPU to consult and collaborate with the parlia -ment and govern-ment on technical election-manage-ment issues.8 Academics as

well as NGOs such as Cetro and Formappi criticised the new law for increasing the risk of the KPU becoming politicised. They argued that the perceived neutral -ity and competence of the Commission would be critical in the upcoming elec-tions, particularly if the result was close and the integrity of the election process came into dispute.9 Party representatives were last allowed on the KPU board for

the 1999 elections; that commission was widely viewed as the most shambolic of the post-Soeharto era. By contrast, the most effective commission was the one that oversaw the 2004 elections; it was made up mainly of specialists from academic and NGO circles.

The Andi Nurpati case serves as another warning about the downside of hav-ing KPU oficials who are too close to political parties. Andi Nurpati, a former KPU board member, stands accused of involvement in the fabrication of a Con -stitutional Court ruling on the allocation of a parliamentary seat in the 2009 elec-tion, although she denies the charge. She is suspected of having conspired with the Court’s clerical staff to alter the ruling in order to deliver the seat to Dewi Yasin Limpo from the People’s Conscience Party (Partai Hati Nurani Rakyat, or Hanura). Last year, Andi caused a stir when she resigned from the KPU to join the board of PD in order to pursue her own political career. Questions are now being raised about whether another six MPs may have gained their seats fraudulently.10

Regional elections were another area where the parliament and the ment combined to push for the scaling back of democratic processes. The govern-ment has long argued that the popular election of governors, and to a lesser extent district and deputy district heads, is harmful to the quality of regional administra-tion and to eficient and harmonious relaadministra-tions between the central government and the regions. There is also widespread concern about the cost, disruption and sometimes conlict caused by the succession of local elections. In 2010, Minister for Home Affairs Gamawan Fauzi announced that the government wanted to eliminate gubernatorial elections and return to the pre-reformasi system of local legislatures electing governors and deputy governors. He also called for the abo-lition of the paired candidate system for district head elections. In subsequent elections only the district head would be popularly elected, and would select the deputy from the ranks of the bureaucracy.11 The minister claimed that the

8 ‘KPU wajib konsultasi dengan DPR [KPU obliged to consult parliament]’, Kompas,

10/8/2011; ‘House passes KPU bill into law’, Jakarta Post, 21/9/2011; ‘Peran partai politik

dominan; UU segera diuji [The dominant role of political parties; law soon to be tested]’,

Kompas, 21/9/2011.

9 ‘Kemandirian KPU harus dijaga [KPU’s independence must be guarded]’, Kompas,

6/4/2011.

10 ‘Kursi tidak sah di DPR [Parliamentary seats invalid]’, Kompas, 14/9/2011.

11 ‘Partai harus biayai calon kepala daerah [Parties have to fund district head candi-dates]’, Kompas, 25/1/2011; ‘Wakil kepala daerah ditunjuk kepala daerah terpilih dari PNS [Deputy district heads appointed from bureaucracy by elected district heads]’, Jawa Pos Online, 26/4/2010.

340 Greg Fealy

changes would make the system cheaper, more administratively streamlined and less prone to corruption. But although reducing the number of regional elections would undoubtedly save money, it would also crimp local democracy and invest greater power in the parties and elites that dominate regional politics. The bill to amend local elections is still to come before parliament.

The trend with these institutional and electoral changes is to cement and expand the power of the current political elite by allowing it to dominate key decision-making processes and limit independent monitoring of its activities. In a political system in which access to vast sums of money is increasingly important to electoral success, all major parties have an interest in being able to use parlia-mentary and ministerial positions to generate funds. The Nazaruddin scandal, described below, provides a graphic example of how parties and ambitious politi-cians depend on accumulating the inancial reserves needed to fund high-proile campaigns. With nearly all these regressive institutional ‘reforms’, the space for civil society is diminished and the scope for elite control extended.

Not only are political leaders undermining the integrity of democratic institu-tions, they are also failing to address mounting problems within the party system. During 2011, more evidence emerged of the slide in public conidence in par -ties and in willingness to afiliate with them. Surveys conducted by the respected Indo nesian Survey Institute (Lembaga Survei Indo nesia, or LSI) show that only 20% of respondents regard themselves as ‘close’ to a particular party, down from 86% in 1999 (LSI 2011: 30). This implies that some 80% of the electorate is willing to change its vote. Coupled with this is the declining vote for major parties and the increase in the number of small parties. In 1999 there were ive parties exceed -ing 3% of the vote; in 2004 this expanded to seven and in 2009 to nine. The shares of the ive ‘big’ parties in 1999 – PDI–P, Golkar, PKB, PPP and PAN12 – dropped

on average by 9% over the next two elections. The result is a more complex politi-cal constellation, which inevitably gives rise to a more variegated ruling coalition with the attendant risk of declining coherence. Despite widespread publicity for such indings and lobbying of political leaders to embark on reforms, few parties have shown any interest in doing so, and most remain preoccupied with their immediate electoral prospects. The only initiative undertaken by the major par-ties has been to raise the threshold for parliamentary representation above the present level of 2.5% of the vote (probably to 3–5%), in a bid to prevent smaller parties from gaining seats and thereby maximise by default their own parliamen-tary representation.13

SBY has contributed to this gradual democratic reversal, most commonly by refusing to defend the country’s democratic institutions unless prompted to do so by public opinion, but also, at times, by directly undermining them. For example, he appears to approve of the plans to scrap gubernatorial elections, seemingly because he believes that governors elected by local legislatures rather than by the

12 PDI–P: Partai Demokrasi Indo nesia-Perjuangan (Indo nesian Democratic Party of Struggle); Golkar: Partai Golongan Karya (Golkar Party); PKB: Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa (National Awakening Party); PPP: Partai Persatuan Pembangunan (United Development Party); PAN: Partai Amanat Nasional (National Mandate Party).

13 ‘Partai masih beda pendapat [Parties still of different views]’, Kompas, 7/1/2011; ‘Anca -man ambang batas [The threat of threshold limits]’, Kompas, 13/9/2011.

people will be more compliant to the wishes of the central government. Similarly, he has raised no objections to the presence of party politicians on the KPU board. Pointedly, SBY has at times joined in criticism of the Commission, claiming that it has ‘extraordinary powers’ and seems ‘answerable only to God’. He was also slow to act on the attempted prosecution of two KPK chairs in 2009 – until polling showed that most voters wanted the charges against them dropped.14

THE NAZARUDDIN SCANDAL AND DEMOCRAT PARTY DIVISIONS

As in every year since Soeharto’s downfall, 2011 has produced a string of corrup-tion scandals that have captured media and public attencorrup-tion. The Minister for Manpower and Transmigration, Muhaimin Iskandar, has been embroiled in graft allegations involving several of his subordinates and is currently under question-ing from the KPK and facquestion-ing calls to step down,15 while the Minister for Social

Ser-vices in the previous government, Bachtiar Chamsyah, was gaoled for 20 months for his role in a corrupt deal. The Bank Century scandal that so dominated politics in 2010 continues to generate occasional headlines, though little progress has been made in uncovering unlawful activity by those involved. But the scandal which caused the greatest sensation was that surrounding Muhammad Nazaruddin, a 33-year-old parliamentarian and, until recently, the national treasurer of PD.

The story irst broke in April 2011, when the KPK arrested a number of ofi -cials and business people, including the secretary of the Ministry for Youth and Sports Affairs, Waid Muharram, over $360,000 in bribes paid to secure the con -tract to build the athletes’ dormitory for the Southeast Asian Games, which are to be staged in Palembang in late 2011. Among those detained was an employee of one of Nazaruddin’s companies who told the KPK that Nazaruddin had received a 13% ‘fee’ for arranging the contract. Waid also revealed that the Minister for Youth and Sports Affairs, Andi Mallarangeng, had been present at the meeting at which the contractor had been decided and had voiced no objection to the arrangement.16

The scandal spread quickly from there. Nazaruddin denied all of the allega-tions and retaliated by threatening to reveal the involvement in corrupt behav-iour of many PD colleagues and other parliamentarians. At a meeting at SBY’s residence in May, for example, it is said that he brazenly told the president that his son, Edhie Baskoro Yudhoyono, together with Andi Mallarangeng and Andi’s brother, the trusted PD political consultant Zulkarnain ‘Choel’ Mallarangeng, were all implicated in corruption, and threatened to release evidence to support

14 ‘SBY’s commitment to graft eradication questioned’, Jakarta Post, 29/6/2009; ‘Indo nesian

president will not interfere in corruption ighters’ detention’, Jakarta Globe, 31/10/2009; ‘President’s inaction only hurts him’, Jakarta Post, 13/11/2009.

15 ‘Dirjen tahu soal uang 1.5 milyar [Director general knows about the 1.5 billion issue]’, Kompas, 13/9/2011; ‘Minister, budget committee leaders face KPK questioning’, Jakarta Post, 4/10/2011.

16 ‘Graft suspect implicates Democratic Party politician’, Jakarta Post, 29/4/2011; ‘Kader berulah, Demokrat babak belur [Cadres misbehave, Democrats black and blue]’, Gatra,

22/6/2011.

342 Greg Fealy

his claim.17 He later accused the chair of PD, Anas Urbaningrum, of also being

party to inancial misdealings.

The Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court, Mahfud MD, then revealed that Nazaruddin had paid S$120,000 as a ‘friendship gift’ to the Court’s secre-tary general in late 2010. When the oficial tried to return the money, Nazaruddin reportedly said that he would ‘trash’ the Court’s reputation if the payment was returned. Although Mahfud informed the president about the ‘gift’, no action was taken against Nazaruddin. Other cases of dubious Nazaruddin dealings began to emerge – most notably his involvement in education ministry corruption – and his wife also came under investigation for graft.18

The Nazaruddin case exposed, for the irst time, the deep cleavages within PD. The main polarity was between the factions centred on SBY, who chairs the party’s Patrons Council, and supporters of Anas Urbaningrum. Relations between SBY and Anas had been strained since the PD Congress in early 2010, when the lat-ter had defeated the president’s preferred candidate, Andi Mallarangeng, for the position of chair. Nazaruddin was a key inancial supporter of Anas’s campaign and had arranged much of the funding for his extensive travel and generous dis-bursements to regional branches in the run-up to the congress. An indication of Anas’s gratitude to and trust in Nazaruddin came immediately after the congress, when the new chair ignored the wishes of the president’s wife that an SBY loyalist become treasurer and instead appointed Nazaruddin to the position. Anas clearly expected that Nazaruddin would continue to raise large sums of money both for the party and for his own tilt at the 2014 presidential elections, as either a presi-dential or a vice-presipresi-dential candidate. The vast lows of money passing through the parliament were the main source of Nazaruddin’s funds. His free-wheeling fund-raising activities were well known within the party and he had developed a reputation as a brash, often imprudent, political entrepreneur.

Relations between Anas and the palace deteriorated markedly from late 2010, when the chair ignored SBY’s wishes on a succession of party issues. The presi-dent and his wife had indicated that they wanted the governor of North Sulawesi to become the next provincial chair but Anas threw his weight behind the mayor of Manado, who was eventually successful. He has similarly nominated loyalists to party positions in Java and Sumatra, much to the chagrin of SBY. This seems to have conirmed the view within the palace that Anas cannot be trusted to protect the interests of the president’s family after 2014, so it is now actively undermining him.

This, then, is the context for the Nazaruddin scandal. The anti-Anas forces wanted immediate disciplinary action against Nazaruddin, knowing that this would weaken Anas, perhaps irretrievably, while Anas’s circle strove initially to defend Nazaruddin on the grounds that nothing had been proven against him and he had been an energetic supporter of the party. The more outspoken leaders

17 ‘Karena Nazar tak mau sendiri [Because Nazar does not want to go alone]’, Tempo,

30/5/2011; ‘Nazaruddin tak ingin pulang [Nazaruddin does not want to return home]’,

Kompas, 2/7/2011.

18 ‘Nazaruddin membangkang, Demokrat gamang [Nazaruddin objects, Democrats in a faint]’, Gatra, 8/6/2011; ‘Kader berulah, Demokrat babak belur [Cadres misbehave, Demo -crats are black and blue]’, Gatra, 22/6/2011.

from each camp openly attacked each other and the press was illed with reports on the growing rancour within the PD elite. Some Anas supporters were con-vinced that their enemies within PD had leaked details of the Nazaruddin case just to harm their leader. Inevitably SBY won the day, and Nazaruddin was dis -missed as party treasurer on 23 May, though he retained his seat in parliament.19

Nazaruddin responded deiantly to his sacking. He slipped out of Indo nesia for Singapore on 23 May, just hours before he was to be barred from leaving the country. Attempts to persuade him to return to Indo nesia failed. While on the run he kept up a series of interviews and press statements denying the allega-tions against him and accusing other party colleagues and parliamentarians of involvement in graft. He was eventually arrested in a luxury resort in Colombia on 9 August and deported to Indo nesia for prosecution.20 The fallout from the

Nazaruddin case has been considerable. It has tarnished the reputation of PD as a coherent and professional party. To some extent it has also harmed SBY’s stand-ing, with the president clearly unable to persuade the warring factions to conine their differences to the party. The fall in public approval for PD over the past three months is testimony to the impact of the scandal. The issures in the party during 2011 suggest that it may struggle to maintain unity and purpose after SBY ceases to be president.

Even greater harm has been wrought to the prospects of Anas Urbaningrum and Andi Mallarangeng, two promising young politicians who were seen as pos-sible future presidential candidates. According to surveys, Anas in particular had some prospect of being a credible presidential or vice-presidential nominee in 2014. He is an astute political operator; he is ethnically Javanese (almost a neces-sity for serious candidates); and he has Islamic credibility as a former chair of Indo nesia’s largest Muslim student organisation, Himpunan Mahasisiwa Islam (HMI). But he is now tainted and without his main inancial benefactor. As the Nazaruddin saga and inevitable trial drag on over the next year or so, Anas is unlikely to be able to escape further damage to his reputation. Similarly, Andi is facing continuing investigation of his own and his department’s role in the scandal, and is also under pressure over delays in preparations for the Southeast Asian Games.

THE CONTINUING SLIDE OF POLITICAL ISLAM

Another major development in the 2009 general election was the continuing decline of Islamic parties. The nine Islamic parties that contested the election gained 29.3% of the national vote, the lowest total ‘Islamic vote’ in any of Indo-nesia’s democratic elections since 1955. Of the four main Islamic parties – PKB, PPP, PAN and PKS – all but PKS suffered falls in support. Even in the case of PKS the igure rose by only 0.5%, despite its leaders’ conidence that the party’s vote would rise by a third or more. The reasons for the parties’ poor performance included internal ructions, lacklustre or incompetent leadership, perceived lack of economic competence and friction with core constituencies (Fealy 2009; Mietzner

19 ‘Kader berulah, Demokrat babak belur [Cadres misbehave, Democrats are black and blue]’, Gatra, 22/6/2011.

20 ‘Indo nesian fugitive arrested in Colombia’, Straits Times, 9/8/2011.

344 Greg Fealy

2009). Many commentators and Islamic leaders have warned the Islamic parties that they will need to rethink their strategies and behaviour if they are to avoid sliding into electoral oblivion over the next decade. With parliamentary thresh-olds likely to rise in 2014, PKB, PPP and PAN face the possibility of not gaining any seats at the next election.

In the past two years, Islamic parties have done little to respond to the chal -lenges they face and many display symptoms of irretrievable decay. PKB con-tinues to suffer internal strife and has made little headway in efforts to improve relations with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), Indo nesia’s largest Islamic organisation and the main basis for its support. PKB’s chair, Muhaimin Iskandar, who is also Minister for Manpower and Transmigration, has been discredited by his minis-try’s mishandling of foreign worker issues and corruption allegations relating to his personal staff. PPP is also languishing. Its lacklustre chair, Suryadharma Ali, who is also the Minister for Religious Affairs, was re-elected party chair at the PPP Congress in 2011, seemingly for his capacity to dispense patronage rather than for any vision or distinguishing leadership qualities. No substantive policy initiatives emerged from the congress and the event closed early, as if there were no signii -cant problems requiring discussion. PAN’s situation is similar to that of PKB and PPP. Its chair, Hatta Rajasa, is preoccupied with his tasks as Co ordinating Minister for the Economy and conidant to SBY, and relations between PAN and its main constituency in Indo nesia’s largest modernist Islamic organisation, Muhammadi -yah, are cool.

The leaders of PKB, PPP and PAN do not appear able to generate ideas to recapture the imagination or trust of the Islamic community; nor are they capable of making a compelling case as to why overtly Islamic parties are more worthy of Muslims’ support than religiously neutral parties such as PD, Golkar and PDI–P. Indeed, the central tactic for political survival of all three parties is participation in the ruling coalition, as this brings access to inancial resources and opportunities to dispense patronage. Not surprisingly, polling conducted by LSI in May 2011 indicates continuing slippage in Islamic party support, with PKB on 4.5%, PKS on 4.1%, PPP on 4.0% and PAN on 2.4%, giving a total Islamic party vote of just 15% (LSI 2011: 16).

The Islamic party that has arguably fared worst over the past year is PKS, though the nature of its problems differs from that of the three parties just men-tioned. Many in PKS regard 2011 as an annus horribilis in which the party has been beset by a succession of controversies that have greatly tarnished its standing as a ‘clean’, reformist and morally exemplary party. PKS began the year in the uncomfortable position of having to defend one of its star recruits to parliament, the former deputy national police chief, Adang Daradjatun, who refused to dis-close the whereabouts of his fugitive wife, Nunun Nurbaeti. Nunun conveniently developed amnesia and sought treatment in Singapore when it emerged that she was being investigated for bribing MPs to ensure the appointment of Miranda S. Goeltom as Bank Indonesia’s senior deputy governor in 2004.21

In March, the party was buffeted when one of its elders, a wizened, wispy-haired preacher called Yusuf Supendi, went public with allegations of corruption

21 ‘PKS legislator refuses to say where fugitive wife is hiding’, Jakarta Globe, 30/5/2011; ‘Sakit lupa ingat belanja [Amnesia but remembers to shop]’, Gatra, 8/6/2011.

and unethical behaviour by the PKS elite. Among his many allegations were claims that the party secretary general, Anis Matta, had misused some $1.25 mil-lion of campaign funds in 2009; that PKS had breached the election law in 1999 by accepting funding from overseas, to wit the Middle East; that Anis and the party’s paramount leader, Hilmi Aminuddin, had received payments from former armed forces commander Wiranto in 2004 to secure party support for his presidential nomination; and that party president Luthi Hasan Isyaaq had accepted $4.25 million from former Vice President Jusuf Kalla during the latter’s presidential campaign.22 Supendi later submitted documents to the KPK and iled a lawsuit

against 11 senior PKS leaders. His allegations caused consternation in party ranks, as he had a reputation for humility and moral rectitude and was known to be a stickler for detail. While there had previously been occasional reporting of divi-sions and malfeasance within PKS, this was the irst time that a senior igure had been willing to make detailed claims. Supendi’s allegations sparked several weeks of damaging media revelations about the high-living lifestyles of the PKS elite.23

The following month PKS was again in the headlines when one of its MPs, Ariinto, was photographed watching pornography on his tablet computer dur -ing a plenary session of parliament. He initially denied that he had intention-ally accessed an adult website but subsequent photographs clearly showed him browsing a menu of pornographic sites.24 Ariinto agreed to resign a few days

later, but attracted more unlattering headlines when it was revealed that he was still drawing a parliamentary salary in September.25 The Ariinto case was acutely

embarrassing for PKS because the party, and in particular its outspoken Minister for Information and Communication, Tifatul Sembiring, had led a controversial campaign to block access to pornographic websites in Indo nesia. Ariinto him -self had been a co-founder of Sabili magazine, for many years the highest-selling Islamist magazine and a regular fulminator against the evils of pornography. Upon hearing of Ariinto’s actions, PKS parliamentarian Nasir Jamil probably summed up the views of many party cadres when he exclaimed: ‘My! PKS’s image is ruined again’.26

The most recent blow for the party came with a series of Tempo articles expos-ing the involvement of senior PKS leaders in the brokerexpos-ing of meat imports. According to Tempo, two of PKS’s most powerful igures, Hilmi Aminuddin and Suripto, had been pressuring staff at the Ministry of Agriculture to issue meat

22 ‘Top PKS politicians face embezzlement allegations’, Jakarta Globe, 15/3/2011; ‘Pres -iden PKS dilaporkan ke BK DPR [PKS pres-ident reported to parliament’s Ethics Board]’, Republika, 17/3/2011; ‘Adil di sini, sejahtera di sana [Just here, prosperous there]’, Tempo,

28/3/2011; ‘Urgently needed: truly clean and caring party’, Jakarta Post, 15/4/2011.

23 See, for example, ‘Deciphering the inluence of PKS puppet-master Hilmi’, Jakarta Post,

30/3/2011.

24 ‘Ariinto: paripurna sudah dalam kondisi jenuh [Ariinto: I was already fed up with the

plenary session]’, Media Indo nesia Online, 8/4/2011; ‘PKS member trapped by anti-porn stance’, Jakarta Post, 9/4/2011; ‘Fotografer punya 60 frame foto Ariinto nonton video por

-no [Photographer has 60 photo frames of Ariinto watching porn]’, detikNews, 10/4/2011. 25 ‘PKS porn scandal lawmaker still in house’, Jakarta Globe, 8/9/2011.

26 ‘Nasir Jamil: waduh … PKS ancur lagi [Nasir Jamil: My … PKS ruined again]’, Media Indo nesia, 9/4/2011.

346 Greg Fealy

import licences to business people connected to the party, and to approve meat shipments from India despite the risk of disease entering the country. One of the brokers reportedly pushing for access to the lucrative permits was Hilmi’s young-est son, Ridwan Hakim.27 The Minister for Agriculture is Suswono, a PKS leader,

and the party has been systematically entrenching its cadres in key positions within the ministry since it irst gained control of it in 2004.

The revelations and accusations concerning PKS have a broader signiicance for Islamic politics. Numerous observers have warned that PKS seems to be cre -ating a new kind of political Islam in Indo nesia, one that is more ideologically driven, puritanical and transnational than the creed of any other Islamic party. With its Muslim Brotherhood-derived doctrine and organisational principles, PKS has been seen as a harbinger of a more Middle Eastern form of Islamism. Certainly the party’s internal discourse abounds with the rhetoric of social and political transformation undergirded by Islamic values (Bubalo and Fealy 2005: ch. 4). Some writers have gone so far as to describe PKS as an insidious and ulti-mately undemocratic force, based on the assumption that if it gained power, it would replace popular sovereignty with a theocracy.28

But developments over the past year suggest that PKS is not so much trans-forming Indo nesian politics as being transformed by it. The low ethical standards of much of Indo nesia’s political elite, its vaulting rent seeking, its nepotism and its disdain for grassroots sentiment are now evident in the upper levels of PKS, though certainly not to the degree found in other parties. It seems likely that the imperatives of electoral politics in Indo nesia will continue to erode the principles and rectitude of the party. PKS won a dramatic increase in its vote in 2004, partly because it was seen as a fresh alternative voice in Indo nesian politics. By 2014, PKS may appear rather too similar to other run-of-the-mill Islamic parties.

AHMADIYAH AND THE LIMITS OF RELIGIOUS TOLERANCE

‘Moderate Muslim’ is probably the term most frequently used by international leaders to describe contemporary Indo nesia, and many Indo nesian leaders trade heavily on their nation’s reputation as one of the most tolerant Muslim-majority countries. SBY, himself, makes regular reference to religious moderation when addressing foreign audiences, often suggesting that other parts of the Muslim world could learn from Indo nesia’s example. For a genuine democracy, reli -gious pluralism and the protection of minority rights are core elements. Mature democracies should have detailed statutes enshrining religious rights, while also ensuring that law enforcement agencies uphold the sanctity of such laws without prejudice.

Despite perceptions within Indo nesia and internationally, the incidence of reli -gious sectarianism has been growing for several years, often with the conniv-ance or indifference of state authorities. This intolerconniv-ance takes numerous forms,

27 ‘Impor renyah “daging berjanggut” [Soft and crunchy imports of “bearded meat”]’,

Tempo, 14/3/2011; ‘Pemain daging Partai Sejahtera [Prosperous Party’s meat players]’, Tempo, 14/3/2011; ‘Partai putih di pusaran impor daging [Pure party at centre of meat imports]’, Tempo, 6/6/2011.

28 See, for example, Dhume (2005).

from low-level harassment and legal restrictions to damage of property, enforced re location and bloody violence. The most frequent form relates to prohibitions on the building of houses of worship, most commonly churches but also on occasion mosques and Buddhist temples. One widely reported case concerns the refusal of the Bogor municipality to agree to the construction of a church despite a Supreme Court ruling conirming the legality of the building permit. Bogor’s mayor ignored the court order and has now decreed that no church may be erected in a street bearing an Islamic name. The central government has taken no action against the mayor, and the Minister for Home Affairs, Gamawan Fauzi, has sup -ported the right of the Bogor administration to reject proposals to construct places of worship.29 Several NGOs that monitor religious intolerance have noted that

abuses of religious rights jumped sharply in 2010 and 2011. The Moderate Muslim Society, for example, recorded 81 serious cases of abuse in 2010, a 30% increase on the previous year, and the Setara Institute, in a similar survey, found 196 cases, or double the number in 2009.30 A former state secretary and noted liberal Muslim

intellectual, Djohan Effendi, has described the past two years as the worst for religious freedom since independence, a view echoed by former Muhammadiyah chair Ahmad Syaii Maarif.31

By far the most egregious and systematic religious rights abuses were experi-enced by the Ahmadiyah sect, which has a membership estimated to be between 50,000 and several hundred thousand. Ahmadiyah sees itself as part of the Mus-lim community, but most MusMus-lims object to the sect, primarily because its founder, Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908), proclaimed himself a prophet in contraven -tion of the Qur’anic statement that Muhammad was the inal messenger of God. Although Ahmadiyah has been present in Indo nesia since 1925 and one of its leaders served briely in a Soekarno-led cabinet in the mid-1960s, in recent dec -ades opposition to the group has intensiied. In 1980, the National Council of Indo nesian Ulama (Majelis Ulama Indo nesia, or MUI) declared Ahmadiyah a deviant sect and called on the government to ban it, though no action was taken. It repeated its call in 2005, and three years later the government issued a Joint Ministerial Decree limiting Ahmadiyah’s outreach activities but stopping short of proscription.32

On 6 February 2011, the most shocking act of religious violence in several years occurred in the Cikeusik sub-district of Banten. A mob of more than 1,000 people attacked the house of an Ahmadiyah family, accusing them of proselytising in the local community. Although the family itself had been evacuated by the police, 17 Ahmadis remained behind to guard the house. Within half an hour, three of them had been beaten to death, ive seriously injured, and the house and vehicles torched. A young Ahmadi ilmed the entire attack, including the gruesome killing

29 ‘Bogor pressed once again to re-open church’, Jakarta Globe, 15/6/2011; ‘Churches can’t

be built in streets with Islamic names: Bogor mayor’, Jakarta Globe, 19/8/2011.

30 ‘Tahun kelam beragama [Gloomy year to be religious]’, Kompas, 22/12/2011; ‘Wave of

religious intolerance intensiies’, Jakarta Globe, 30/12/2011.

31 ‘Kebebasan beragama di Indo nesia dinilai suram [Religious freedom in Indo nesia seen

as bleak]’, Kompas, 19/12/2010.

32 For more information on Ahmadiyah in Indo nesia, see Ahmad (2007) and Crouch

(2011).

348 Greg Fealy

of his colleagues. On the video, the police can be seen standing by as the Ahmadis are savagely beaten, intervening only when the victims are dead.33 When the

video footage made it onto the internet and into television broadcasts, there was immediate public revulsion at the violence and demands for the police to act. Eventually 12 people were charged, including one of the Ahmadis who had been trying to defend the house. All were subsequently found guilty and gaoled for between three and six months, with the Ahmadi – whose hand had been almost severed in the attack – receiving the equal-longest sentence.34

The politics surrounding the attack and its aftermath were revealing, particu-larly the responses of the SBY government and Islamic leaders. The initial public sympathy for those killed and injured proved short-lived, and within days of the attack the Cikeusik Ahmadis had gone from victims to villains. Numerous Islamic politicians argued that the Ahmadis had provoked the attack by refusing to halt their preaching, and said that the sect should be banned in order to prevent fur-ther communal disorder.

Government ministers helped to harden public attitudes against Ahmadiyah. The Minister for Justice and Human Rights at the time, Patrialis Akbar, a senior Muhammadiyah member and PAN politician, told the press that he had no rea-son to believe that the Ahmadis’ human rights had been breached.35 The

Minis-ter for Religious Affairs, Suryadharma Ali, repeatedly criticised Ahmadis during the following weeks for offending Muslims with their beliefs and urged them to ‘rejoin’ the Islamic community. A week after the attack, Minister for Home Affairs Gamawan Fauzi met a number of the most virulent anti-Ahmadiyah campaigners, including Habib Rizieq Shihab from the Islamic Defenders Front (Front Pembela Islam, or FPI), at a meeting he described as ‘warm and friendly’.36 The Minister for

Defence, Purnomo Yusgiantoro, endorsed a ‘prayer mat’ operation during which soldiers in West Java and Banten ‘occupied’ Ahmadiyah mosques seeking to ‘per-suade’ Ahmadis to return to the ‘true path’. Purnomo’s approval came despite NGO claims that dozens of Ahmadis had been coerced into renouncing their

33 Extracts from the video, most carrying warnings of their graphic nature, can be found

on YouTube: <http://www.youtube.com/verify_age?next_url=http%3A//www.youtube. com/watch%3Fv%3DeGAycEJeq5o>.

34 The trial was itself controversial. One of the judges repeatedly berated the Ahmadi ac-cused and made critical remarks about his faith, prompting Human Rights Watch Asia to

refer the matter to the Judicial Commission. Footage of the trial can be found on YouTube: <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5ryhl_no3I>. Upon handing down the inal ver -dict, the senior judge defended the light sentences given to the attackers, saying that the vigilantes had been provoked by the Ahmadis and had shown remorse. Little remorse was evident, however, when the attackers were released from gaol and greeted by cheering

crowds. See ‘Hakim sidang Cikeusik: vonis pidana sudah patut dan adil [Cikeusik case judge: criminal verdict is itting and just]’, Republika Online, 28/7/2011; ‘Cikeusik verdicts handed down with disbelief’, Jakarta Globe, 29/7/2011.

35 ‘Menkumham: jangan langsung simpulkan insiden Cikeusik langgar HAM [Justice and Human Rights Minister: don’t immediately conclude the Cikeusik incident breaches hu -man rights]’, detikNews, 8/2/2011.

36 ‘Mendagri rembukan dengan FPI cs [Home Affairs Minister confers with FPI et al.]’,

detikNews, 16/2/2011.

faith.37 SBY was more circumspect, denouncing the violence and calling on the

police to apprehend those who had broken the law. As in past cases of Ahmadiyah attacks, he carefully avoided naming the organisation, probably because he did not want to be seen as defending it, but also quite possibly because, like so many Indo nesian Muslims, he actively dislikes Ahmadiyah and its beliefs.38

The central government applauded moves by a number of provincial and dis-trict governments to ban Ahmadiyah in their regions, usually on the grounds of preserving public order. The administrations in Pekanbaru, Garut and Tasik malaya sought to halt all Ahmadiyah activities, and the governors of South Sulawesi, West Java and East Java issued orders either restricting or proscribing the organi-sation. The legality of these regional instructions is open to question given that Indo nesia’s regional autonomy laws state that only the national government has authority over religious affairs. At least three ministers – the Ministers for Justice, Home Affairs and Religious Affairs – backed the local administrations for assist-ing the national government in implementassist-ing its Joint Ministerial Decree and for safeguarding the purity of religious teachings.39

If the government was outspoken in support of regional Ahmadiyah bans, it was surprisingly silent on another dimension of the controversy. After the Cikeusik attack, a number of Islamist groups declared that SBY should either ban Ahmadiyah or stand down as president. Several prominent leaders, includ-ing FPI’s Habib Rizieq and Munarman, spoke openly of overthrowinclud-ing the gov -ernment if there was no action on Ahmadiyah,40 while former general Tyasno

Sudarto and Abu Jibril, the leader of the Indo nesian Mujahidin Council (Maje -lis Mujahidin Indo nesia, or MMI), conirmed that they had drawn up plans for an Islamic revolution.41 These threats drew no response from the government or

its security services. Their inaction on this occasion contrasted sharply with the prompt arrest, prosecution and gaoling of student protesters and critics who had ridiculed or ‘insulted’ the president in previous years. The most notorious case was that of a student who was gaoled for daubing the letters ‘SBY’ on a water buf-falo.42 Yet on the issue of Ahmadiyah, Islamist leaders were seemingly immune

from investigation despite repeated subversive statements.

In response to criticism of the Ahmadiyah attack by human rights groups, many Indo nesians have argued that the issue has been blown out of proportion and that most minorities live peacefully and without intimidation. While there is a good

37 ‘Menag: operasi sajadah untuk Ahmadiyah ajakan persuasive [Religious Affairs Min

-ister: prayer mat operation for Ahmadiyah is a persuasive offer]’, detikNews, 15/3/2011;

‘Indo nesia denies forced religious conversions’, Jakarta Globe, 16/3/2011.

38 ‘Presiden: cari pihak yang bertanggungjawab [President: ind those responsible]’,

Kompas, 8/2/2011.

39 ‘Pelarangan Ahmadiyah di daerah dianggap sesuai [Ahmadiyah bans in regions re-garded as appropriate]’, Republika Online, 21/3/2011.

40 ‘FPI ancam gulingkan Yudhoyono [FPI threatens to overthrow Yudhoyono]’, Tempo-Interaktif, 11/2/2011.

41 ‘Plot to undermine Indo nesian president’, Al-Jazeera, 22/3/2011, <http://english. aljazeera.net/video/asia-paciic/2011/03/2011322402237872.html>; ‘Retired generals

us-ing Islamic groups in attempt to topple president: report’, Jakarta Globe, 22/3/2011. 42 ‘SBY takes offence at protesting buffalo’, Jakarta Post, 3/2/2010.

350 Greg Fealy

deal of truth to this, it is the exceptional rather than the general cases that offer the more exacting measure of tolerance, and on this score Indo nesia fails the test. Three particular criticisms can be levelled at the SBY government and its law enforcement agencies. First, they have not upheld the rule of law. The police had prior knowledge of the Cikeusik attack but failed to prevent it. While the attack was under way, police looked on as lives were taken and property destroyed. The sentences for the 11 attackers were manifestly inadequate given the three deaths, and the one Ahmadi on trial endured hostile questioning from the judges about his faith. In stark contrast, mention could be made of the two Baha’i adherents who were recently gaoled for ive years in Lampung for holding interfaith meet -ings for children.

Second, the right to religious freedom is universal and is enshrined in the Con-stitution as well as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, to which Indo-nesia is a signatory. Yet the Ahmadiyah case shows that Indo Indo-nesia is selective in its application of this principle. The Ahmadis are an almost friendless sect in Indo nesia, with few prominent igures willing to defend it. Some of this is indeed due to Ahmadiyah’s own exclusivity and political missteps. But it is precisely Ahmadiyah’s unpopularity that makes it a searching test case. In many parts of Indo nesia, Ahmadiyah is a persecuted minority that can expect little or no protec -tion from the state.

Third, the government’s handling of the Ahmadiyah issue exacerbates reli-gious intolerance by emboldening sectarian vigilantes. These Islamist activists are politically savvy and opportunistic; they are able to sense when political and social conditions favour them, as they do with the Ahmadiyah issue. The govern-ment’s failure to respond resolutely to the Islamists’ subversive threats and con -tinuing intimidation of Ahmadiyah is interpreted as either tacit approval or fear of retribution. It is doubtful that the SBY government wants to fan intolerance, but it unwittingly does so when it fails to act.

Some observers have predicted that the Ahmadiyah case marks the beginning of a trend towards ever greater circumscription of religious life, both by the state and by activist Islamist groups. They speculate that the campaign of intimidation directed at Ahmadiyah will be followed by more intense targeting of other ‘devi-ant’ sects such as the Shia and the many local heterodox variants of Islam.43 This

is unlikely, primarily because the Ahmadiyah case is sui generis. Such is the across-the-board loathing of Ahmadiyah that it has a uniting effect on Muslim opinion. No other group is in this position. The Shiites, for example, are politically well connected, attract considerable interest and sympathy among well-to-do urban Muslims, and enjoy the backing of Iran, an increasingly important trading part -ner for Indo nesia. Similarly Christians, despite their dificulties in being able to construct churches, are nonetheless able to count on state protection, due in no small measure to their political and economic clout as well as their prominence as media owners and intellectuals. While Islamists may continue to criticise these minorities and mobilise against them, they are unlikely to gain the support of the broader Muslim community or to receive any backing from the government in the form of ‘turning a blind eye’.

43 ‘Shiites fear they are the next target’, Jakarta Globe, 14/3/2011.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

There is much to celebrate about Indo nesia’s democratisation process since 1998. The country is much freer and fairer than at any time since the early 1960s. Basic rights, such as the right to elect and remove a government, to associate freely, to have substantial freedom of speech and belief, and to have laws applied fairly, are generally observed. But evidence has also emerged in 2011 that the process of reform has ground to a halt or gone into reverse in a number of ields, albeit not in a dramatic way as yet. Left to their own inclinations, the Indo nesian government, parliament and parties would proceed with the democratic clawback, seeking not so much fundamentally to change the present system as to curtail scrutiny of their own activities and narrow the space for civil society oversight and counter-pressure.

The contours of the current phase of politics have become easier to discern over the past year. Competing with SBY’s concern for development and good governance is his preoccupation with securing his place in history and the future of his family. His desire for popularity and recognition of his presidential achieve-ments – which, to date, are far more modest than his supporters proclaim – often runs counter to good decision making. Meanwhile, the internal divisions of SBY’s Democrat Party and its reliance on the president himself for much of its cohesion have been exposed. Political Islam also appears incapable of addressing its own slide and the party system in general is badly in need of revitalisation, though few within the elite are disposed to address this. Compared to most other countries in the region, Indo nesia still scores relatively well on democracy and human rights, but the trend line points down, not up.

REFERENCES

Ahmad, Munawar (2007) ‘Faith and violence’, Inside Indo nesia 89 (January–March),

avail-able at <http://www.insideIndo nesia.org/edition-89/faith-and-violence-1407014>. Aspinall, Edward (2010) ‘Indo nesia: the irony of success’, Journal of Democracy 21 (2): 20–34.

Bubalo, Anthony and Fealy, Greg (2005) ‘Joining the caravan? The Middle East, Islam

-ism and Indo nesia’, Lowy Institute Paper 05, Lowy Institute for International Policy,

Sydney.

Butt, Simon (2011) ‘Anti-corruption reform in Indonesia: an obituary?’, Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 47 (3): 381–94, in this issue.

Crouch, Melissa (2011) ‘Religious “deviancy” and law’, Inside Indo nesia, 25 August, available

at <http://www.insideIndo nesia.org/stories/religious-deviancy-and-law-28081471>. Dhume, Sadanand (2005) ‘Indo nesian democracy’s enemy within: radical Islamic party

threatens Indo nesia with ballots more than with bullets’, YaleGlobal, 1 December,

avail able at <http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/Indo nesian-democracy’s-enemy-within>.

EIU (Economist Intelligence Unit) (2008) Index of Democracy 2008, EIU, London.

Fealy, Greg (2009) ‘Indo nesia’s Islamic parties in decline’, Inside Story, 11 May, available at

<http://inside.org.au/Indo nesia%e2%80%99s-islamic-parties-in-decline/>.

Haris, Syamsuddin (2011) ‘Negara tersandera politik busuk [State hostage to rotten poli-tics]’, Kompas, 5 February.

Kuncoro, Mudrajad, Widodo, Tri and McLeod, Ross H. (2009) ‘Survey of recent develop-ments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 45 (2): 151–76.

LSI (Lembaga Survei Indo nesia) (2011) ‘Pemilih mengambang dan prospek perubahan

kekuatan partai politik [Floating voters and the prospects for political party power]’,

352 Greg Fealy

LSI, Jakarta, 15–25 May, available at <http://www.lsi.or.id/riset/403/Rilis%20LSI%20 29%20Mei%202011>.

Manning, Chris and Purnagunawan, Raden M. (2011) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 47 (3): 303–32, in this issue.

Mietzner, Marcus (2009) ‘Indo nesia’s 2009 elections: populism, dynasties and the consoli

-dation of the party system’, Analysis, Lowy institute for International Policy, Sydney,

May.

Mietzner, Marcus (2011) ‘Indo nesia’s democratic stagnation: anti-reformist elites and resil -ient civil society’, Democratization, iFirst, available at <http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/135

10347.2011.572620>.

Schütte, Soie Arjon (2011) ‘Appointing top public oficials in a democratic Indonesia: the

Corruption Eradication Commission’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 47 (3): 355– 79, in this issue.

BOX 1 The WeakeningOf deMOcracyandThe cOsTsOf cOnsensus

While Indonesia’s economic prospects continue to improve, democratic reform has

stalled. A key indicator of stagnation is the appearance of efforts to weaken or reduce the effectiveness of a wide range of oversight agencies, both those set up in the early years of reformasi and the few pre-existing agencies that were reinvigorated after 1998. The efforts to weaken the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) and the election management bodies are by now well recognised. However, a number of other, less well-known, agencies that play an important role in the democratisation process have also been undermined or neglected.

One example has been parliament’s (ultimately unsuccessful) efforts to weaken

the Financial Transaction Reports and Analysis Center. This inluential agency tracks the inancial transactions of allegedly corrupt oficials, then collaborates closely with the KPK and the Judicial Maia Taskforce in the investigative and prosecutorial processes. Upon realising in 2010 that the agency was instrumental in enabling the

KPK to convict numerous MPs, factions in parliament sought to weaken it. A second example concerns the failure to strengthen the National Ombudsman Commission, which monitors and oversees the quality of public services, but which conspicuously

lacks the authority to enforce its rulings. Oficials are able to ignore the Ombudsman

with impunity. Parliament has shown no interest in strengthening its mandate, or in enhancing its ability to sanction government authorities that disregard its rulings.

Three other potentially important oversight and anti-corruption agencies are the

Police Commission, the Prosecutorial Services Commission within the Attorney Gen

-eral’s Ofice (AGO) and the Supreme Audit Agency (BPK), the latter established as

long ago as 1946. NGOs note that the Police Commission is under pressure not to investigate alleged police involvement in crime and abuses of power. The

Commis-sion is housed inside police headquarters and is chaired by retired police oficers. It

has failed to provide any genuine oversight of the Police, despite the presidential ‘order’ that it monitor police performance more effectively. Similarly, the independent

Prosecutorial Services Commission, which is supposed to scrutinise the AGO’s

anti-corruption procedures, lacks support from both the legislative and executive branches of government. Early in the reformasi period, the BPK redeined its role essentially to become a companion agency to the KPK in ighting graft through forensic audits. In

2009 parliament appointed a new BPK leadership, under which the agency has largely withdrawn from its widely applauded anti-corruption work. Public sector accounting

reform is discussed in greater detail in Kuncoro, Widodo and McLeod (2009: 171–4).

The leadership style of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) can be seen as a constraint to reform but also as a guarantee of stability – at least until 2014. SBY pur-sues an extreme form of consensus and inclusivity, even though contentious policy matters rarely lend themselves to unanimity in a democracy. His apparent insistence on full agreement among coalition members has been a factor in slowing or stalling reform in such areas as fuel subsidies, rice imports, civil service restructuring, foreign direct investment, infrastructure and competitiveness. Repeatedly in public

state-ments, SBY has made clear his preference for gradualism, conlict avoidance and com -promise over strong policy or performance, regardless of the issue. With this as the over-riding approach to leadership, we should not expect any sweeping reforms in

the next three years. Meanwhile, middle-class Indonesians – especially the younger, self-conident, more sophisticated ones, are coming to believe that a little more dis -cord and elite contestation might improve governance and the quality of democracy.

Douglas Ramage