xiv

ABSTRACT

Firmus Madhu Dhengi, 2017, Potential Difficulties for Nataia Speakers in Learning English Phonology, Yogyakarta, English language Studies Graduate Program, Sanata Dharma University.

Nataia, a small language in central Flores, is showing early signs of being endangered. Its native speakers, for instance, now tend to use Bahasa Indonesia as alingua franca in their communication with other ethnic groups around them, pushing their own language to a passive position. The present writer, therefore, considers it important to take necessary measures to prevent the language from further endangerment. The first step taken is to formally set its phonology down to formal writing. The phonology of the language is then compared and contrasted with that of English in order to find their similarities and differences. Attention will be directed especially to the differences that contrastive analysts claim to be potential trouble spots. That is exactly what this thesis entitled ‘Potential Difficulties for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology’ is attempting to reveal.

For a start, the present writer uncovered all the segmental phonemes of Nataia. Both the vowel and consonant phonemes of the local language were extracted by means of commutation tests and minimal set tests from Oko Utu and the lexicon of the present writer as a native speaker of the language. Oko Utu is a research text that contains an account of how an extended family of Nataia gets together to solve their common problems. The long tradition has it that the main speaker of the forum opens the gathering with a long introduction in which he shows off his ability to use traditional proverbs and sayings. In addition to the moral values, the proverbs and sayings also contain all the segmental phonemes of the local language, five of which i.e., /ɗ/, /ř/, /ɣ/, /ğ/ and / β/ turn out to be unique. The revelation of all the segmental phonemes of Nataia leads to the answer to the first research question of this thesis “what are the vowel and consonant phonemes found in Nataia?”.

Secondly, the writer conducted a Constrastive Analysis (CA) of Nataia and English phonology. The result of the CA clearly indicates that English possesses /θ/, /ð/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /tʃ/, and /dʒ/, six characteristic consonant phonemes of the language which are absent from the inventory of Nataia. The problem begins when a Nataia speaker learning English p h o n o l o g y tries to find the ‘ substitutes’ for these ‘unknown’ sounds from the inventory of his or her own language. As a result, the substitution gives rise to a problem of ‘intelligibility’, at least of irritation or amusement. The revelation of the problematic English phonemes leads to the answer to the second research question of this thesis“What segmental English phonemes may cause difficulties for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology?”.

To solve these segmental phonological problems, English teachers may begin with exercises in which one difficult sound is contrasted with another in minimal pairs. At the same time, they can ask their students to find the native pronunciation of words containing the difficult sounds in digital dictionaries. However, they should avoid over-dwelling on the accurate production of these individual sounds. Thus, they should immediately assign their students to read aloud passages in which these problematic sounds appear in connected speech.

xv

produce and recognize sounds in isolation, but in larger forms such as words, phrases and sentences. In fact, a Nataia speaker learning English will have to exert extra efforts because Nataia is a syllable-timed language, whereas English is a stress-timed language. The revelation of the stress and rhythm problems leads to the answer to the third research question of this thesis“What suprasegmental phonemes of English may cause difficulties for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology?”.

To alleviate the pinch of suprasegmental problems, English teachers may begin with drills on ‘word stress’ from a particular word list. Then, they can ask their students to find in a digital dictionary where the primary stress of a certain word is assigned. Later, they have to provide higher units of utterance such as phrases and sentences in which rhythmic patterns of English are extensively exhibited.

xvi ABSTRAK

Firmus Madhu Dhengi, 2017, Potential Difficulties for Nataia Speakers in Learning English Phonology. Yogyakarta, English language Studies Graduate Program, Sanata Dharma University.

Nataia, sebuah bahasa kecil di Flores tengah, mulai menunjukkan tanda-tanda terancam. Para penutur aslinya, misalnya, sekarang cenderung memakai Bahasa Indonesia sebagailingua franca dalam komunikasi kesehariannya dengan suku-suku lain di sekitar mereka. Akibatnya, bahasanya sendiri terdesak ke posisi pasif. Dengan alasan ini, penulis merasa perlu mengambil langkah guna melindungi bahasa itu dari ancaman lebih lanjut. Langkah pertama ke arah sana adalah menuliskan fonologinya secara formal. Lalu, fonologi Nataia diperbandingkan dengan fonologi Inggris untuk mencari persamaan dan perbedaannya. Perhatian diarahkan secara khusus pada perbedaan yang menurut para analis kontrastif berpotensi menimbulkan masalah. Memang inilah yang akan dibeberkan lewat tesis berjudul ‘Potential Difficulties for Nataia Speakers in Learning English Phonology’ ini.

Sebagai langkah awal, penulis lebih dahulu menyingkapkan semua fonem Nataia. Fonem- fonem itu diperoleh melalui tes-tes komutasi dari Oko Utu dan leksikon penulis sendiri sebagai penutur asli bahasa Nataia. Oko Utu adalah teks riset yang berisikan cerita tentang cara sebuah keluarga besar Nataia menyelesaikan persoalan mereka secara bersama. Menurut tradisi, pembicara utama dalam forum itu membuka pertemuan tersebut dengan mengutip sejumlah peribahasa dan pepatah. Selain mengandung ajaran moral, peribahasa dan pepatah itu juga berisikan fonem-fonem segmental bahasa Nataia, lima di antaranya yaitu /ɗ/, /ř/, /ɣ/, /ğ/ and /β/ terbilang unik. Penyingkapan semua fonem Nataia itu menjawab pertanyaan pertama dalam formulasi masalah tesis ini “Apa saja fonem vokal dan konsonan yang terdapat dalam bahasa Nataia?”

Selanjutnya, penulis mengadakan Analisis Kontrastif antara fonologi bahasa Nataia dan Inggris. Hasilnya menunjukkan bahwa bahasa Inggris memiliki /θ/, /ð/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /tʃ/ dan /dʒ/, enam fonem khas Inggris yang tidak terdapat dalam daftar fonem bahasa Nataia. Muncul persoalan ketika seorang penutur Nataia yang mempelajari bahasa Inggris mencari pengganti bagi fonem-fonem asing itu dalam daftar fonem bahasa ibunya. Akibatnya, bisa muncul persoalan ‘kesalahpahaman’, setidaknya rasa risi atau rasa geli. Penyingkapan enam fonem khas Inggris yang menimbulkan kesulitan dalam pelafalan itu akan menjawab pertanyaan kedua dalam formulasi masalah tesis ini “Fonem segmental dalam bahasa Inggris manakah yang bisa menimbulkan kesulitan bagi penutur bahasa Nataia dalam mempelajari fonologi bahasa Inggris?”

Sebagai langkah awal guna membereskan persoalan fonologis segmental ini, guru bahasa Inggris bisa menggunakan latihan di mana suatu fonem dikontraskan dengan fonem lain melalui pasangan minimal. Guru juga perlu meminta anak didiknya mengecek pelafalan asli kata-kata yang memuat fonem-fonem sulit itu di kamus digital. Akan tetapi, guru tidak perlu berlama-lama melatih pelafalan fonem-fonem segmental yang sulit itu. Mereka mesti segera menugaskan peserta didiknya ‘membaca lantang’ suatu bacaan di mana fonem-fonem itu berfungsi dalam suatu arus ujaran. Membaca lantang itu bisa dilakukan secara perorangan maupun secara bersama.

xvii

suku kata dalam suatu ujaran. Lain halnya dengan b ahasa Inggris yang tekanan katanya sangat bervariasi dan berfungsi untuk mengatur irama dalam bertutur. Penyingkapan perbedaan dalam hal ‘tekanan dan ritme’ ini akan menjawab pertanyaan ketiga dalam formulasi masalah tesis ini “Fonem suprasegmental Inggris mana saja yang bisa menyulitkan penutur Nataia dalam mempelajari fonologi bahasa Inggris?”.

Sebagai langkah awal guna membereskan masalah suprasegmental ini, guru bisa mengandalkan dril mengenai tekanan kata dari sebuah daftar kosa kata. Guru bisa juga meminta anak didiknya mengecek tekanan sebuah kata dalam kamus digital. Kemudian guru harus memperkenalkan satuan-satuan ujaran yang lebih besar semisal frase dan kalimat. Soalnya, di sana akan tampak lebih jelas pola-pola ritmis yang khas Inggris.

POTENTIAL DIFFICULTIES FOR NATAIA SPEAKERS IN

LEARNING ENGLISH PHONOLOGY

A THESIS

Presented as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain theMagister Humaniora (M.Hum.)Degree in

English Language Studies

by

Firmus Madhu Dhengi 146332003

GRADUATE PROGRAM OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

i

POTENTIAL DIFFICULTIES FOR NATAIA SPEAKERS IN

LEARNING ENGLISH PHONOLOGY

A THESIS

Presented as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain theMagister Humaniora (M.Hum.)Degree in

English Language Studies

by

Firmus Madhu Dhengi 146332003

GRADUATE PROGRAM OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES

SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

YOGYAKARTA

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The writer would first of all like to express his deepest and sincerest gratitude to Dr F. B Alip MPd, MA, academic advisor of this thesis, for his untiring and meticulous guidance without which this work could not have been completed.

The writer also feels very much indebted to Prof Dr Soepomo Poedjosoedarmo Ph.D, Dr B.B Dwijatmoko MA, Drs F.X Mukarto Ph.D, Drs Barli Bram M.Ed. Ph.D, Dr Novita Dewi M.S, M.A, Dr J. Bismoko and Dr E. Sunarto M.Hum, for their professional expertise and personal views which have in one way or another contributed to the completion of this study.

The writer would also like to thank his friend Erik Christopher, who edited part of this work and translated some Nataia proverbs and sayings into English.

The writer’s deepest and heartfelt thanks also go to Hendra Soenardi Law Firm, which has granted him a scholarship for this graduate study. The writer understands that the scholarship would not have been offered without the benevolent heart of his younger brother and former student, Edi Hendra SH. MML.

The writer would also like to dedicate this thesis especially to his beloved wife, Maria Arita Listyandari, who has been so loving and faithful all along. The last but not the least, may God the Merciful bless anyone to whom the writer has reasons to be grateful.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

COVER PAGE... i

APPROVAL PAGE... ii

THESIS DEFENSE APPROVAL PAGE... iii

STATEMENT ON ORIGINALITY... iv

LEMBARAN PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI... v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS... vi

1.1 Background of the Study... 1

1.2 Statements of the Problems... 6

1.3 Purpose of the Study ... 6

1.4 Significance of the Study... 7

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW... 8

2.1 Review of Related Theories... 8

2.1.1 Nataia and Foreign Language Studies ... 8

2.1.2 Nataia and Language Family ……... 12

2.1.3 Nataia and Verbal Preservation ... 14

viii

2.1.4.2.6 Palatal... 21

2.1.4.2.7 Velar... 21

2.1.4.2.8 Glottal... 22

2.1.5 English Manner of Articulation... 22

2.1.5.1 Voiced and Voiceless... 22

2.1.8.3 Movement Against Contrastive Analysis... 31

2.1.8.4 In Defense of Contrastive Analysis... 33

2.2 Review of Related Studies... 35

2.3 Theoretical Framework... 38

CHAPTER 3: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY... 41

3.1 Object of the Study... 41

3.2 Type of Research... 41

3.3 Procedure of Data Collection... 42

3.4 Procedure of Data Analysis... 44

CHAPTER 4: RESULTS AND ANALYSIS ... 47

ix

4.1.1 Nataia Vowel Phonemes... 47

4.1.2 Nataia Consonant Phonemes... 5 3 4.1.2.1 Places of Articulation... 54

4.2 English Segmental Phonemes with Potential Difficulties...… 66

4.3 English Suprasegmental Phoneme with Potential Difficulties... 77

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS... 85

5.1 Conclusions... 85

5.1.1 Difficulties Behind Nataia Segmental Phonemes ……… 85

5.1.2 English Segmental Phonemes and Potential Hurdles... 87

5.1.3 Suprasegmental Phoneme with Potential Difficulties.…... 89

5.2 Suggestions... 91

x

5.2.3 Textbook Writers ………... 93

REFERENCES... 9 4

xi

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1 English Consonant Chart ... 24

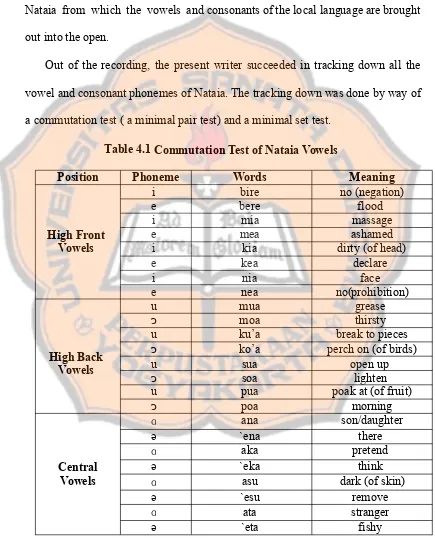

Table 4.1 Commutation Test of Nataia Vowels... 48

Table 4.2 Contrast of Vowel Length... 49

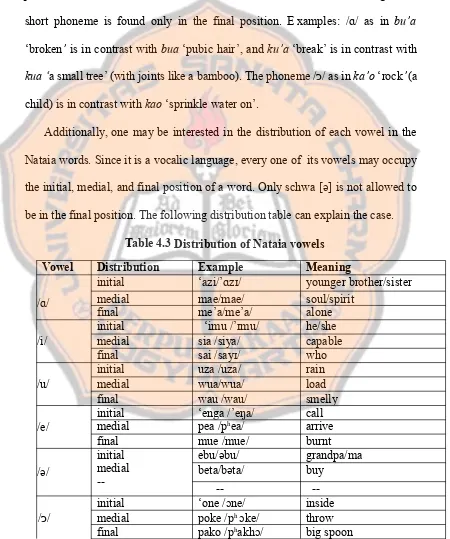

Table 4.3 Distribution of Nataia vowels... 50

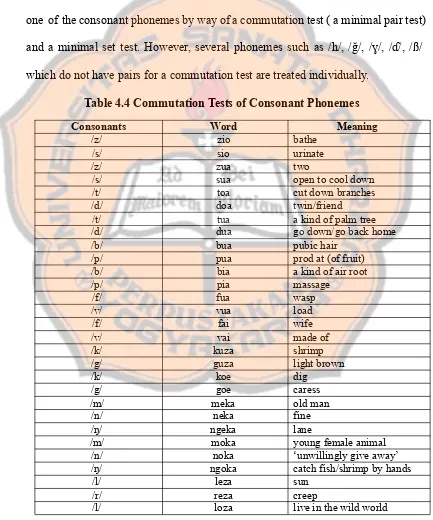

Table 4.4 Commutation Tests of Consonant Phonemes... 53

Table 4.5 Bilabial Sounds... 55

Table 4.6 Labiodental Sounds... 55

Table 4.7 Dental Sounds... 55

Table 4.8 Alveolar Sounds... 56

Table 4.9 Alveo-Palatal Sounds... 56

Table 4.10 Retroflex Sounds... 57

Table 4.11 Velar Sounds... 57

Table 4.12 Glottal Sounds... 58

Table 4.13 Nasal Sounds... 59

Table 4.14 Stops Sounds... 60

Table 4.15 Fricative Sounds... 61

Table 4.16 Tap / Trill... 61

Table 4.17 Lateral Sound... 61

Table 4.18 Implosive Sounds... 62

Table 4.19 Comparison of English and Nataia Phonemes... 67

xii

LIST OF FIGURES

xiii

LIST OF APPENDICES

xiv

ABSTRACT

Firmus Madhu Dhengi, 2017, Potential Difficulties for Nataia Speakers in Learning English Phonology, Yogyakarta, English language Studies Graduate Program, Sanata Dharma University.

Nataia, a small language in central Flores, is showing early signs of being endangered. Its native speakers, for instance, now tend to use Bahasa Indonesia as alingua franca in their communication with other ethnic groups around them, pushing their own language to a passive position. The present writer, therefore, considers it important to take necessary measures to prevent the language from further endangerment. The first step taken is to formally set its phonology down to formal writing. The phonology of the language is then compared and contrasted with that of English in order to find their similarities and differences. Attention will be directed especially to the differences that contrastive analysts claim to be potential trouble spots. That is exactly what this thesis entitled ‘Potential Difficulties for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology’ is attempting to reveal.

For a start, the present writer uncovered all the segmental phonemes of Nataia. Both the vowel and consonant phonemes of the local language were extracted by means of commutation tests and minimal set tests from Oko Utu and the lexicon of the present writer as a native speaker of the language. Oko Utu is a research text that contains an account of how an extended family of Nataia gets together to solve their common problems. The long tradition has it that the main speaker of the forum opens the gathering with a long introduction in which he shows off his ability to use traditional proverbs and sayings. In addition to the moral values, the proverbs and sayings also contain all the segmental phonemes of the local language, five of which i.e., /ɗ/, /ř/, /ɣ/, /ğ/ and / β/ turn out to be unique. The revelation of all the segmental phonemes of Nataia leads to the answer to the first research question of this thesis “what are the vowel and consonant phonemes found in Nataia?”.

Secondly, the writer conducted a Constrastive Analysis (CA) of Nataia and English phonology. The result of the CA clearly indicates that English possesses /θ/, /ð/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /tʃ/, and /dʒ/, six characteristic consonant phonemes of the language which are absent from the inventory of Nataia. The problem begins when a Nataia speaker learning English p h o n o l o g y tries to find the ‘ substitutes’ for these ‘unknown’ sounds from the inventory of his or her own language. As a result, the substitution gives rise to a problem of ‘intelligibility’, at least of irritation or amusement. The revelation of the problematic English phonemes leads to the answer to the second research question of this thesis“What segmental English phonemes may cause difficulties for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology?”.

To solve these segmental phonological problems, English teachers may begin with exercises in which one difficult sound is contrasted with another in minimal pairs. At the same time, they can ask their students to find the native pronunciation of words containing the difficult sounds in digital dictionaries. However, they should avoid over-dwelling on the accurate production of these individual sounds. Thus, they should immediately assign their students to read aloud passages in which these problematic sounds appear in connected speech.

xv

produce and recognize sounds in isolation, but in larger forms such as words, phrases and sentences. In fact, a Nataia speaker learning English will have to exert extra efforts because Nataia is a syllable-timed language, whereas English is a stress-timed language. The revelation of the stress and rhythm problems leads to the answer to the third research question of this thesis“What suprasegmental phonemes of English may cause difficulties for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology?”.

To alleviate the pinch of suprasegmental problems, English teachers may begin with drills on ‘word stress’ from a particular word list. Then, they can ask their students to find in a digital dictionary where the primary stress of a certain word is assigned. Later, they have to provide higher units of utterance such as phrases and sentences in which rhythmic patterns of English are extensively exhibited.

xvi

ABSTRAK

Firmus Madhu Dhengi, 2017, Potential Difficulties for Nataia Speakers in Learning English Phonology. Yogyakarta, English language Studies Graduate Program, Sanata Dharma University.

Nataia, sebuah bahasa kecil di Flores tengah, mulai menunjukkan tanda-tanda terancam. Para penutur aslinya, misalnya, sekarang cenderung memakai Bahasa Indonesia sebagailingua franca dalam komunikasi kesehariannya dengan suku-suku lain di sekitar mereka. Akibatnya, bahasanya sendiri terdesak ke posisi pasif. Dengan alasan ini, penulis merasa perlu mengambil langkah guna melindungi bahasa itu dari ancaman lebih lanjut. Langkah pertama ke arah sana adalah menuliskan fonologinya secara formal. Lalu, fonologi Nataia diperbandingkan dengan fonologi Inggris untuk mencari persamaan dan perbedaannya. Perhatian diarahkan secara khusus pada perbedaan yang menurut para analis kontrastif berpotensi menimbulkan masalah. Memang inilah yang akan dibeberkan lewat tesis berjudul ‘Potential Difficulties for Nataia Speakers in Learning English Phonology’ ini.

Sebagai langkah awal, penulis lebih dahulu menyingkapkan semua fonem Nataia. Fonem- fonem itu diperoleh melalui tes-tes komutasi dari Oko Utu dan leksikon penulis sendiri sebagai penutur asli bahasa Nataia. Oko Utu adalah teks riset yang berisikan cerita tentang cara sebuah keluarga besar Nataia menyelesaikan persoalan mereka secara bersama. Menurut tradisi, pembicara utama dalam forum itu membuka pertemuan tersebut dengan mengutip sejumlah peribahasa dan pepatah. Selain mengandung ajaran moral, peribahasa dan pepatah itu juga berisikan fonem-fonem segmental bahasa Nataia, lima di antaranya yaitu /ɗ/, /ř/, /ɣ/, /ğ/ and /β/ terbilang unik. Penyingkapan semua fonem Nataia itu menjawab pertanyaan pertama dalam formulasi masalah tesis ini “Apa saja fonem vokal dan konsonan yang terdapat dalam bahasa Nataia?”

Selanjutnya, penulis mengadakan Analisis Kontrastif antara fonologi bahasa Nataia dan Inggris. Hasilnya menunjukkan bahwa bahasa Inggris memiliki /θ/, /ð/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /tʃ/ dan /dʒ/, enam fonem khas Inggris yang tidak terdapat dalam daftar fonem bahasa Nataia. Muncul persoalan ketika seorang penutur Nataia yang mempelajari bahasa Inggris mencari pengganti bagi fonem-fonem asing itu dalam daftar fonem bahasa ibunya. Akibatnya, bisa muncul persoalan ‘kesalahpahaman’, setidaknya rasa risi atau rasa geli. Penyingkapan enam fonem khas Inggris yang menimbulkan kesulitan dalam pelafalan itu akan menjawab pertanyaan kedua dalam formulasi masalah tesis ini “Fonem segmental dalam bahasa Inggris manakah yang bisa menimbulkan kesulitan bagi penutur bahasa Nataia dalam mempelajari fonologi bahasa Inggris?”

Sebagai langkah awal guna membereskan persoalan fonologis segmental ini, guru bahasa Inggris bisa menggunakan latihan di mana suatu fonem dikontraskan dengan fonem lain melalui pasangan minimal. Guru juga perlu meminta anak didiknya mengecek pelafalan asli kata-kata yang memuat fonem-fonem sulit itu di kamus digital. Akan tetapi, guru tidak perlu berlama-lama melatih pelafalan fonem-fonem segmental yang sulit itu. Mereka mesti segera menugaskan peserta didiknya ‘membaca lantang’ suatu bacaan di mana fonem-fonem itu berfungsi dalam suatu arus ujaran. Membaca lantang itu bisa dilakukan secara perorangan maupun secara bersama.

xvii

suku kata dalam suatu ujaran. Lain halnya dengan b ahasa Inggris yang tekanan katanya sangat bervariasi dan berfungsi untuk mengatur irama dalam bertutur. Penyingkapan perbedaan dalam hal ‘tekanan dan ritme’ ini akan menjawab pertanyaan ketiga dalam formulasi masalah tesis ini “Fonem suprasegmental Inggris mana saja yang bisa menyulitkan penutur Nataia dalam mempelajari fonologi bahasa Inggris?”.

Sebagai langkah awal guna membereskan masalah suprasegmental ini, guru bisa mengandalkan dril mengenai tekanan kata dari sebuah daftar kosa kata. Guru bisa juga meminta anak didiknya mengecek tekanan sebuah kata dalam kamus digital. Kemudian guru harus memperkenalkan satuan-satuan ujaran yang lebih besar semisal frase dan kalimat. Soalnya, di sana akan tampak lebih jelas pola-pola ritmis yang khas Inggris.

1

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background of the Study

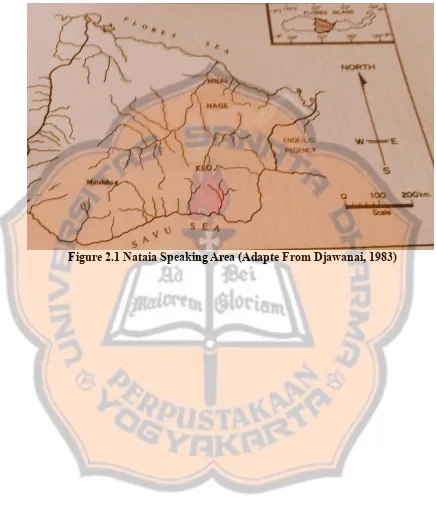

Nataia people, a small ethnic group living on the north central part of the island of Flores, speak a language that is also known as Nataia language. The area where t h e l a n g u a g e i s s p o k e n is part of Nagekeo, a newly established regency that broke away from the Regency of Ngada in 2007. Both Ngada and Nagekeo are parts of the Province of the Southeast Islands.

The figures indicating the precise number of speakers of Nataia are not available. However, the educated guess is that they could be around four thousand. This estimate is based on the recent local government data taken before the regional election in 2008 in which the first regent of Nagekeo was elected. The data show that the number of eligible voters from four villages (Watuwawi, Boanio, Kotakisa, and Boaroja) where the language is spoken is approximately three thousand people. According to the electoral law, eligible voters must be at least 17 years of age. Thus, the government data imply that the reasonable number of Nataia speakers may range from a little below to a little above four thousand after those under 17 are counted and included.

Historically and politically, the area where Nataia is spoken today was formerly part of Onderafdeling Nage. For almost four decades (1907-1945), the onderafdeling was ruled by a local king appointed by the Dutch colonial government. Below the puppet ruler whose royal palace was in the village of

commands (Steffan Dietrich, 1942). One of them was the chief of Gemente Nataia who lived in the village of Nataia, on the north-central slope of the Lambo (also known as Amegelu) mountain. A few years after the Indonesian independence in 1945, all the inhabitants of the village of Nataia moved downwards to the level land, close the meadow of Malawitu, and established new villages which are Boanio, Watuwawi, Kotakisa and Boaroja of today.

From these four villages, the people of Nataia can now witness a new development in the history of their language. The local language which has so far been transmitted only verbally is beginning to be formally set down in writing and described linguistically. Therefore, now the people of Nataia have a good reason to be excited because their language is being introduced to the global linguistic community. The logical implication is that Nataia will from now on be part of the written linguistic wealth of the world. Though what is presently introduced is limited to the phonetic and phonological systems of the language, it can still be considered a humble contribution in the absence of any older texts of the language. The present discussion and description of Nataia is based primarily on Oko Utu, a research text that was read by four native speakers of the language in

October of 2015. Oko Utu, the literal meaning of which is ‘gathering to

contribute’, comprises 128 simple sentences that contain adequate information about the phonetic and phonological system of the language.

the Ngada-Lio language grouping (Verheijen, 1977). The bigger members of the group which have a larger number of speakers include Ngadha, Nage, Keo, Ende, and Lio.

Outside Flores, quoting Mansoer Pateda (1977) and Abdul Muthalib (1985), Soepomo explains, there are a number of other vocalic languages all over Sulawesi, from Gorontalo in the north all the way down to Kendari in the Southeast. This explanation implies that very few out of more than seven hundred languages in Indonesia are vocalic (Kompas, com, 03 February, 2011). All these vocalic languages share one specific feature i.e., every one of their words ends in a vowel phoneme. Interestingly, in the case of Nataia, even every syllable ends in a vowel phoneme.

The vocalic nature of Nataia may theoretically become a stumbling block for its speakers in learning English phonology. The reason is that a vocalic language such as Nataia does not tolerate any consonant phoneme in the coda position of its words. On the opposite side, English allows a huge number of its syllables and words to end in a consonant phoneme.

Oko Utu text also reveals that most words of Nataia are bisyllabic i.e.,

consisting only of two syllables. A few monosyllabics do exist but they are mostly function words which tend to reduce their vowels to schwa in a sentence (ne in 2 of the appendix). A few trisyllabics and foursyllabics also exist but they are

mostly loan words (sobaza ‘pray’ in 9 of the appendix) or frozen compounds

mosalaki‘honorable people’ (in 1 of the appendix).

Regardless of the number of its syllables, every word of Nataia ends in a

composed of two syllables. The first syllable mo- ends in [ɔ-], while the second

syllable -na ends in [-ɑ]. The same word mona also indicates that the main

syllable structure of Nataia is of the c onsonant v owel (CV) type. The first

syllable of mona is mo- which is composed of one consonant [m] and one

vowel [ᴐ]. The second syllable-nais also composed of one consonant [n] and one vowel [ɑ]. In addition, a word of Nataia also allows a syllable to consist only of one vowel (V) or V type. The worda’i‘leg’( in 100 of the appendix), for instance, a l s o consists of two syllables i.e., [a-] as the first syllable and [ - ’ i ] as the second syllable.

The syllable structures of Nataia which consist simply of one consonant and one vowel (CV) or just one vowel (V) may also be another potential trouble spot for a Nataia speaker in learning English phonology. This is because English allows various patterns of consonants (C) and vowels (V) such as VC (in), V (a), CCV (pre), CV (vi), VC (ǝs) CVC (kæp), CVC (ʃǝn), etc, in the formation of its syllables (Finegan, 2004: 126).

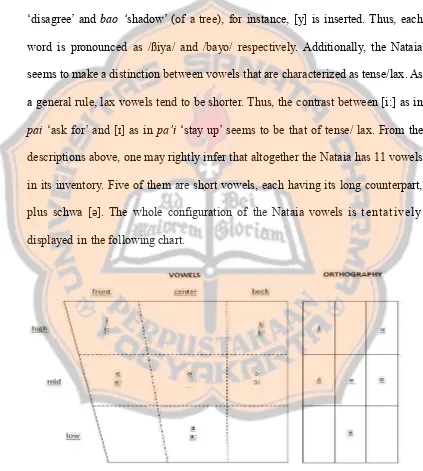

Each word of Nataia consists of one or more syllables and each syllable consists of one or t w o sounds. The speech sounds of Nataia comprise a certain number of vowels and consonants. Both the vowels and consonants of the local language possess certain characteristics that may i g n i t e the inquisitive mind of a linguist. For example, each vowel of Nataia, except the schwa, has its long counterpart. As for consonants, the local language is proud of its five

characteristic sounds i.e., alveolar implosive /ɗ/ as in dhora [ɗᴐrɑ] ‘throw

away’, velar implosive /ğ/ as in ‘geo [ğeᴐ] ‘shine’ , alveolar fricative /ř/

and velar fricative /ɣ/ as in ghama [ɣɑmɑ] ‘grope’ which may lengthen the inventory of unique global speech sounds.

It is to be regretted, however, that two out of the five characteristic sounds of Nataia are being gradually pushed to the sidelines. The way Antonius Moti (42) and Patrisius Seo (40), two out of the four respondents of this study, pronounced the alveolar fricative /ř/ and the velar implosive /ğ/ indicate that the younger speakers are beginning to avoid using the two characteristic sounds. Now the younger speakers seem to prefer using the alveolar trill /r/ instead of the alveolar fricative /ř/. Thus, the words such as rhasa [řɑsɑ] ‘fence’ and rhoba

[řᴐbɑ] ‘sarong’ are now pronounced simply as [rɑsɑ] and [rᴐbɑ], perhaps due to regular contacts with Bahasa Indonesia and neighboring languages or just for easier pronunciation. In addition, the younger speakers also tend to prefer oe[ᴐe] to ‘goe [ğᴐe] for negation, pushing the velar implosive sound [ğ] to a cornered position.

This shift in the phonological preference such as in the use of /r/ instead of /ř/ may be taken simply as an indication of a change or may also be a threat. It is to be noted, however, that there is a bigger problem menacing the existence of Nataia as a whole. Native speakers of the local language are now mingling with transmigrants from different areas who speak different languages. Therefore, they v e r y often have to speak Bahasa Indonesia as a lingua franca in their daily communication, pushing their own language to a passive position.

Nataia is then compared and contrasted with that of English to find their similarities and differences. The comparison and contrast is also expected to answer the research questions of this thesis entitled “Potential Difficulties for Nataia Speakers in Learning English Phonology”.

1.2 Statements of the Problems

This is the very first time Nataia has been set down in formal writing. Therefore, the writer takes advantage of this work to introduce all the phonemes of the local language. At the same time, by way of this work, the writer also tries to find out if there are characteristic phonemes of English that may pose problems for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology. The following research questions are the formulations of the problem statements.

1. What are the vowel and consonant phonemes found in Nataia?

2. What segmental phonemes of English may cause difficulties for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology?

3.What suprasegmental phonemes of English may ca use difficulties for Nataia

speakers in learning English phonology?

1.3 Purpose of the Study

In line with the problem statements above, the writer would in the first place like to discover what vowel and consonant phonemes are found in Nataia. Then the writer studies how these segmental phonemes of the local language are combined to form syllables and words. It is right here that the problems for Nataia speakers studying English phonology begin.

show what specific consonants of English are absent from the inventory of the local language. Contrastive analysists claim that these foreign phonemes are potential trouble spots for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology.

Finally, the writer would like to reveal two suprasegmental phonemes of English whose nature is quite different from those of Nataia. This difference in nature turns out to be the reason why these two suprasegmental phonemes cause difficulties for Nataia speakers in studying English phonology.

1.4 Significance of the Study

The present work seems to have the following three benefits:

1. By formally introducing the phonemes of Nataia, the present writer wants to make sure that the local language is also preserved in its written form. Besides, the revelation of the phonemes of the local language may help to lengthen the list of unique global speech sounds.

2. Comparison and contrast of Nataia phonology with that of English may reveal which characteristic English phonemes may pose problems for Nataia speakers in learning English phonology. Then, CA can help English teachers in central Flores as a whole, especially in the Nataia speaking area, to be consciously aware of the problems and prepare necessary steps to help their students surmount the hurdles.

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter presents a review of related theories, a review of related studies and a theoretical framework. The review of related theories comprises some basic ideas in support of this study; the review of related studies reveals contributions of some language scholars to this study; the theoretical review shows how this study was conducted and completed.

2.1 Review of Related Theories

The review of related theories comprises Nataia and Foreign Language Studies, Nataia and Language Family, Nataia and Verbal Preservation, English Articulatory Phonetics, English Manner of Articulations, English Phonological System, English Phonological Processes, and Contrastive Analysis (CA).

2.1.1 Nataia and Foreign Language Studies

In the 1920-s, Nage and Keo were registered among tens of onderafdeling

under the larger AfdelingFlores that was ruled by G.A Bosselaar, the then Dutch

have their own native priests. The local priests were expected to take over the

church leadership from the foreign missionaries in due time (De Katholieke

Missien en het Christelijk Huisgezin, Uden , 1929: 67)

The important fact is that eight decades after its birth, the seminary has yielded a good number of indigenous priests. Of equal importance is that it has produced thousands of graduates who have served as layman leaders of Flores. Of no less importance is the silent agreement among the people of the island that the graduates of the minor seminary were fairly good at foreign languages.

Early graduates of the seminary are reputed to be good at Latin and Dutch, the main language courses in the curriculum of the institution. They are said to have gone through difficult times learning the languages only during the first three years (junior high school). Towards the end of the second three years (senior high school), however, they are said to have begun tasting the “sweet fruits” of their tireless efforts.

seven in the first class of 1929, who wished to identify themselves with the white ruling elite (Plechtige Opening van het nieuwe Seminarie, Uden, 1929: 67).

After Indonesia proclaimed her independence in 1945, Dutch was abolished from the curriculum of the new independent state. Soon after, English replaced it as the main foreign language to be learned at the minor seminary. From early 1950-s to the 1960-s, the English teachers in the institution were native speakers from the United States, at least from countries such as the Netherlands and the Philippines where practically everybody speaks English with some ease. This time the participants who were from different local language backgrounds, mostly from the Ngadha-Lio language grouping of which the Nataia is a member, also turned out to be fairly good speakers of English.

Stephanus Djawanai, a former student of the seminary, recalls how the fourth year students of his generation were often asked by their English teacher to make a short speech or even a sermon in English. “Father Garger also asked us to make daily notes on who we spoke to, what we talked about and how long we made a conversation in English,” Djawanai wrote in “Learning a Language, Opening Up a

Horizon (2004: 99)”, an article in memory of his unforgettable years in the

seminary.

integrated approach in which “listening and comprehension, speaking, reading and comprehension, andwriting” received a relatively balanced treatment.

Unfortunately, the glorious years of foreign language learning in the seminary are now said to be history. In a way, the national policy of the Indonesian government seems to have played a part in the sad story. In the early 1970-s, the Department of Religious Affairs (now Ministry of Religious Affairs) issued a xenophobic decree that offered two difficult choices for every foreign missionary: become a holder of an Indonesian passport or leave the country immediately. Also xenophobic, F.M Parera (2004:15)) notes, was a regulation that all the foreign aids for religious purposes should first be notified to the department. In the aftermath, most white missionaries fled this country. Devoted native speakers of English on duty in the seminary were gone. Also gone were English textbooks and graded story-books that had regularly entered the shelves of the library of the institution.

To sum up, the seminary has witnessed the ‘rise and fall’ of three foreign languages. Initially, it was Dutch that was abolished from the curriculum for reasons of nationalism. Then, Latin was relegated from the church service and the curriculum of the seminary, owing to the decree of the Second Vatican Council in the early 1960-s. The decree stipulated that Latin be no longer‘the one and only’

Another clear proof of our language skill decline was that we were not even able to conduct an English Night or English Day, a showcase in which everyone of the former classes showed off their English speaking skill,” Rano wrote in “In Aeternum Memorandum (2004:205)”.

All the three foreign languages have surely gone past their golden days in the institution. Special notes, however, should be taken about the change of status of Latin. The relegation of Latin by the Papal government proves to have had a far-reaching repercussion. Since then, every national language or even a local language such as Nataia has been permitted to be used during the religious ceremony in the Catholic Church. This is presumably the background reason why in the middle of 1960-s, theCatholic Mission of Florespublished a ‘Prayer and

Hymn’ book entitled Sua Budju Ngadji which accentuated an amalgam of

Nage languages.

The Nataia people enjoyed praying and singing using the book because on the whole they were familiar with a lot of words and expressions in it. However, they wanted more i.e., a special‘prayer and hymn’book of their own in which the characteristic sounds and expressions representing their ethnic, emotional and cultural pride are prominent.

2.1.2 Nataiaand LanguageFamily

to break away and form a separate regency which now claims to have a population of a little over one hundred thousand people.

Though Nagekeo has detached itself from Ngada administratively, the two regencies remain closely affiliated in terms of language. Th e family of Ngadha and Nagekeo languages of which Nataia is a member is generally assumed to belong to the Austronesian family of languages. As for the relationship of Nataia with the surrounding languages, Verheijen (1977) indicates that Nataia belongs to the Ngadha-Lio subgroup, which is part of the larger Bima-Sumba group (in line with Jonker, 1898). This system of language grouping has remained unchallenged for over a century and is still recognized by well-reputed institutions such as the Indonesian National Language Institute. Recently, therefore, Inyo Jos Fernandez (1996: 16) suggested that Jonker’s finding be immediately r e v i s e d a n d updated in order to keep pace with the other latest developments in the Austronesian group studies.

Unfortunately, not a single historical-comparative linguist has come up with a fresh idea that challenges Jonker’s proposition. This fact clearly indicates that Jonker’s way of grouping languages in Flores remains in the status quo. The only new development in the Ngadha-Lio language grouping is that Nataia, one of its members, has finally got its turn to be formally described and analyzed in its own right. Indeed, the present work marks the beginning of a completely new era for Nataia language in which it has started to be formally set down in writing and analyzed linguistically for the very first time.

2.1.3 Nataia and Verbal Preservation

speakers of the language are beginning to avoid using the two characteristic sounds of the Nataia. Though now already in their early forties, Moti and Seo are here representing the younger speakers who show a shift in their phonological preference. The younger speakers are beginning to prefer using the alveolar trill /r/ instead of the alveolar fricative /ř/, perhaps due to regular contacts with Bahasa Indonesia and other neighboring languages or simply for the sake of easier

pronunciation. Thus, words such as rhasa [řɑsɑ] ‘fence’ and rhoba [řobɑ]

‘sarong’ are pronounced simply as [rɑsɑ] and [robɑ]. In addition, the younger speakers also tend to use oe [ɔe ] instead of ‘goe [ğɔe] for negation, putting the implosive velar sound [ğ] in a critical position. This is quite in contrast with Tadeus Leu (72) and Anselmus Jogo (52), two elder respondents for this study, who remain faithful to the traditional way of pronouncing the /ř/ and /ğ/.

This phenomenon is certainly an initial indication that Nataia is undergoing change in which two of its unique phonemes are being gradually pushed out of regular use. The present writer believes that such a change deserves to be set down in formal writing for a historical reason i.e., to remind future generations that the Nataia people have once pushed certain characteristic phonemes out of their language inventory. Furthermore, the urgent need to put everything down in formal writing emphasizes the fact that Nataia has been an entirely oral tradition all along. To put it more aptly, all forms of customs in the language have so far been transmitted simply by direct verbal interactions.

performs much better in public and is well-versed in the use of traditional proverbs and sayings. Additionally, an e l o q u e n t speaker (usually a n e l d e r l y

m a n f rom a high caste referred to as mosalaki) is very familiar with the

traditions and customary laws of the ethnic group.

The special position of an eloquent speaker clearly indicates that traditional proverbs and sayings also play a decisive role in the preservation of the language and the culture of Nataia people. An eloquent speaker usually takes advantage of

Oko Utu,a forum in which all the members of an extended family of Nataia

get together, to remind the p a r t i c i p a n t s to remain faithful to the value system of their community. The powerful instrument of an eloquent speaker i n t h e f a m i l y f o r u m is the traditional proverbs and sayings which contain highly appreciated values such as “trust and listen to God, respect for parents, monogamy, cooperation, friendship, hard work, the need for a precautionary measure, etc”. All these values are neatly hidden within the traditional proverbs and sayings which have been handed down only orally for generations. Oral communication needs to be given a special emphasis here because an eloquent speaker puts all these values across by way of ‘the sounds and sound patterns’ of the local language. To put it in another way, he makes wise use of the power of the phonetic and phonological systems of the Nataia to preserve the language and perpetuate the value system of the small local community.

local language in its written form, starting now with the preliminary study of Nataia phonology.

2.1.4 English Articulatory Phonetics

A comparison and contrast of English and Nataia phonology needs appropriate theories that describe the speech sounds in the two languages: how they are produced and articulated; how they fall into patterns and change in different circumstances; and most importantly, what aspects of the sounds are necessary for conveying the meaning. (Ladefoged, 2005: 1)

Anybody who wants to answer the above questions has no other choice but to go to the phonetic and phonological theories. Phonetics is concerned with descriptions of speech sounds that occur in languages, of course, including English and Nataia. Actually, the first step one should take is to find out what English and Nataia people are doing when they are talking and listening to speech. Fortunately, in the case of English phonology, a large number of phoneticians -Daniel Jones (1938), Ladefoged (1993), Giegerich (1992), Poole (1999), Aitchison (2003) and Collins and Mees (2003) just to mention a few - have agreed to divide the segmental sounds of the language into two types i.e., vowels and consonants.

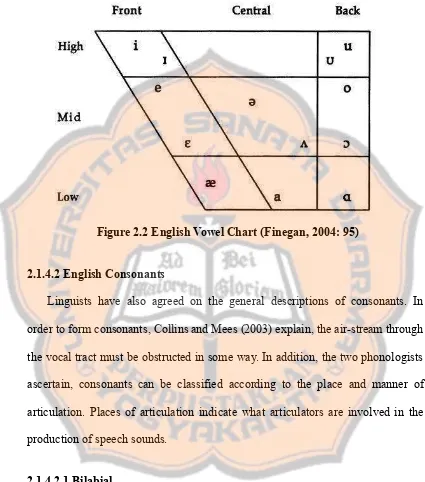

2.1.4.1 English Vowels

raising of different parts of the tongue as well as the extent of the raising. As an example, [i] and [u] are different because [u] is a back vowel, one which is produced with the back of the tongue raised, whereas [i] is a front vowel which is produced with the front of the tongue raised.

There is another important criterion in the classification of vowels i.e., how wide is the mouth open. The vowels [a] and [ɑ] , for instance, have one common feature i.e., they are produced with the mouth wide open. In other words, there is a maximum distance between the tongue and the roof of the mouth. This is a difference in height. Thus, [i] and [u] are high vowels and [a] and [ɑ] are low vowels.

The four vowel sounds, Giegerich (1992) explains, represent the extreme points of the principal dimensions of vowel articulation: height and backness. Thus, [i] is a high front vowel, [u] a high back vowel, [a] a low front vowel and [ɑ] a low back vowel. If the the height of [i]-[a] scale is divided into four points that are of equal distance, Giegerich argues, there will be four vowels that can be symbolized as [i] - [e] - [ɛ] -[a] in the vowel diagram.

For the back series, Giegerich (1992) maintains, one may fill in the corresponding intermediate vowels as [o] and [ɔ], so that [u]-[o]-[ɔ]-[a] represent the set of back reference vowels. This system of reference vowels is known as the Cardinal Vowels Scale (CV Scale) devised by the English phonetician Daniel Jones. In addition, Stuart Poole (1999) explains, vowels made with an open mouth cavity, with the tongue far away from the roof of the mouth, such

surface is close to the roof of the mouth such as /i:/ infleece, the sounds are close vowels.

Figure 2.2 English Vowel Chart (Finegan, 2004: 95)

2.1.4.2 English Consonants

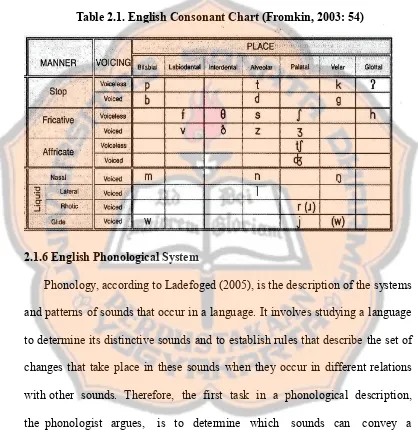

Linguists have also agreed on the general descriptions of consonants. In order to form consonants, Collins and Mees (2003) explain, the air-stream through the vocal tract must be obstructed in some way. In addition, the two phonologists ascertain, consonants can be classified according to the place and manner of articulation. Places of articulation indicate what articulators are involved in the production of speech sounds.

2.1.4.2.1 Bilabial

features. [p] has the features of [- voice, + stop]. [b] has the features of [+voice, + stop] and [m] has the features of [+voice, +stop, + nasal].

2.1.4.2.2 Labiodental

Giegerich (1992) explains that English labiodental sounds i.e., [f],[v]] are produced by raising the lower lip against the upper incisors as in fat and vat. Though both are labiodentals, they are different sounds which are composed of different features. [f] has the features of [+labial, -voice, +fricative] and [v] has the features of [+labial, +voice, + fricative].

2.1.4.2.3 Interdental

According to Giegerich (1992), interdental sounds [θ], [ð] are produced by raising the tip of the tongue against the upper incisors, or inserting it between the

upper and lower incisors as in thigh and thy. The two of them, however, are

discrete sounds which are composed of different features. [θ] has the features of [-voice, + stop, + fricative]. Whereas [ð] has the features of [+ [-voice, + stop, +fricative].

2.1.4.2.4 Alveolar

English alveolar sounds [d],[n],[s],[z],[l],[t], Giegerich explains, are produced by raising the tip of the tongue against the alveolar ridge. Examples are

+fricative, + sibilant]. [l] is composed of features such as [+lateral, approximant, +voice]. [t] is composed of features such as [+stop, - voice].

2.1.4.2.5 Palato-Alveolar

English palatal sounds [ʃ], [Ʒ,] [tʃ], [dƷ], according to Giegerich (1992), are produced by raising the front of the tongue towards the back of the alveolar ridge and the front of the palate as in she and leisure. However, each of them is a discrete sound which is composed of different features. [ʃ] is composed of features such as [+fricative, +sibilant, - voice]. [Ʒ] has the features of [+sibilant, +fricative, +voice]. [tʃ] is composed of features such as [+sibilant, + fricative, -voice].

2.1.4.2.6 Palatal

In the production of a palatal sound [y], Giegerich maintains, the front of the tongue is raised towards the palate, slightly further back than in a palato-alveolar sound. Example: you.

2.1.4.2.7 Velar

English velar sounds [k],[g],[ŋ], according to Giegerich (1992), are produced by raising the back of the tongue towards the the soft palate or velum. Examples:

2.1.4.2.8 Glottal

Glottal sound [h], according to Collins and Mees (2003), is produced when the glottis is open and there is no air stream in the mouth, while [ˀ ] is produced when the air is stopped completely at the glottis by tightly closed vocal cords.

2.1.5 English Manner of Articulation

According to Mees a n d Collins (2003), manner of articulation indicates the how of sound production. All articulations involve a stricture i.e., a narrowing of the vocal tract which affects the air-stream. Collins and Mees explain further that there are three possible types of stricture: complete stricture, close approximation, and open approximation.

2.1.5.1 Voiced and Voiceless

Collins and Mees (2003) explain that the vocal folds vibrate rapidly when the air-stream is allowed to pass between them, producing what is termedvoice- that is, a sort of ‘buzz’ which one can hear and feel in vowels and some consonant sounds. Examples of vowels are [a],[ɪ] as in aim and ink and voiced consonants are [b], [d] as inbindanddine. For voiceless sounds,the two phonologists assert, the vocal cords and the arytenoid cartilage are held wide apart which allows the air stream to escape freely. Examples of voiceless consonants are [t],[ f] as intime

andfine.

2.1.5.2 Oro-nasals

In addition to the articulatory closure in the mouth, Collins and Mees (2003) explain, the soft palate is raised so that the nasal tract is blocked off, then the air stream will be completely obstructed. Pressure in the mouth will build up and an oral stop will be formed. Oral stops include [p],[b],[t],[k] and [g]. When the articulators come apart, the two phonologists explain, the air-stream will be released in a small burst of sound. This kind of sound occurs in the consonants in the words “pie, buy” (bilabial closure), “tie, dye” (alveolar closure) and “kye, guy”(velar closure).

If the air is stopped in the oral cavity but the soft palate is down so that it can go out through the nose, Collins and Mees (2003) explain, the sound produced is a

nasal stop. Sounds of this kind, the two phonologists say, occur at the beginning of the words “my”(bilabial closure) and “nigh” (alveolar closure)and at the end of “sang” (velar closure). Though both the nasal sounds and the oral sounds can be classified as stops, Ladefoged (2005) argues, the term stop by itself is almost always used to indicate an oral stop and the term nasal to indicate a nasal stop. Thus, the consonants at the ends of the words “bad” and “ban” would be called an alveolar stop and an alveolar nasal respectively.

2.1.5.3 Fricatives

2.1.5.4. Affricates

Some sounds are produced by a stop closure followed immediately by a gradual release of the closure that produces an effect characteristic of a fricative. Therefore, Ladefoged (2005) explains, affricates such as [tʃ and [dƷ] are known as a sequence of a stop plus a fricative.

Table 2.1. English Consonant Chart (Fromkin, 2003: 54)

2.1.6 English Phonological System

Phonology, according to Ladefoged (2005), is the description of the systems and patterns of sounds that occur in a language. It involves studying a language to determine its distinctive sounds and to establish rules that describe the set of changes that take place in these sounds when they occur in different relations with other sounds. Therefore, the first task in a phonological description, the phonologist argues, is to determine which sounds can convey a difference in meaning. When two sounds can be used to differentiate words, he asserts, they belong to different phonemes.

notation of which is between slashes, for example, /p/. Variants of a phoneme, as are pronounced in real speech are allophones. Their notation is between brackets, for example, [p]. There is a crucial difference between sounds that are allophonic variants of the same phoneme and two sounds that are different phonemes. If one substitutes a sound by an allophonic variant, Ladefoged asserts, he or she still gets the same word. However, if one substitutes a sound by another belonging to a different phoneme, he or she gets a different word. Thus, a phoneme is a distinctive unit. Phonemes in a normal speech are fused together and influence each other. There are some rules that try to predict how a phoneme will vary in a given context. These are called allophonic rules which facilitate articulation.

2.1.7 English Phonological Processes

A phonological process, Finegan (2004) explains, is a term used to cover the way in which segments are influenced by adjacent segments, causing phonemes to vary in their realization according to a phonological context. There are some types of English phonological processes which include the following:

2.1.7.1 Assimilation

According to Ladefoged (1993), a sound is coloured or adapted to the sound before or after it. In other words, one sound changes into another sound because of the influence of the neighbouring sounds as in the change of underlying /n/ to /m/ in “input” [ɪmput] or of underlying /z/ to /Ʒ/ in “does she” [dʌƷʃi]. A change is also noticed in the compound ‘sun burnt’ of the sentence ‘my skin is sun burnt’

where the alveolar sound [n] in sun changes to bilabial [m] to adapt to the

[mʌɪskɪnɪzsʌmbə:nt].Another example, the sound [k] in speakwhich is voiceless is followed by [s] which is also voiceless in a phrase such as “The man speaks slowly” [ ðə mæn spi:ks slowlɪ],whereas the sound [g] inbegwhich is voiced is

followed by [z] which is also voiced in the sentence such as “He begs her to

forgive him” [hɪ begz ər tə fɔrgɪv əm].

Another case of assimilation is detected in the pronunciation of the following pairs of words. According to Finegan (2004: 116), the vowels of the words on the left column are shorter in duration than those on the right. If one looks past the spelling, one will notice that each word on the left column ends in a voiceless consonant,whereas each word on the right column ends in a voiced consonant. Thus, English lengthens vowels which precede voiced consonants.

Examples:

cap cab

cat cad

back bag

cot cod

2.1.7.2 Aspiration

Aspiration is articulation of a sound that is accompanied by a small emission of air, in a small explosion (Finegan, 2004: 112). A little differently, Ladefoged (1993) formulates aspiration as “a period of voicelessness after the release of an articulation as in “pie” [phaɪ]. Voiceless stops /t, p, k/ are aspirated when they are

in the initial syllable, in words such as (time, pot, cat), but /p, t, k/ are unaspirated in medial position after an /s/ in words like(spew, stew, skip).

2.1.7.3 Deletion

other words such as “aspects [æspeks],he must be [hɪmʌsbɪ],grandpa[græmpa],

postman [pousman],west cliff[wesklif], andhandsome[hænsəm].

2.1.7.4 Insertion or Epenthesis

Insertion or epenthesis, Reima (1989) explains, is a phonological process in which a certain sound is inserted in order to facilitate pronunciation. The phonologist points to the sentence “I am (e) tired” as an example. In practice, the sentence is pronounced as [ʌɪməthɑɪəd]. A sudden transition from [m] which is

bilabial to [t] which is alveolar seems rather difficult. Thus, the [ə] is inserted for easier pronunciation.

2.1.7.5 Phonotactic Rules

Speakers of a language have an implicit knowledge of which are the combination of sounds that are allowed or are frequent in their language. In English, Finegan (2004) explains, having several consonant sounds together is fairly normal. For example:r + k + t as in worked. This pattern will have a very direct influence on an L2 student learning English.

In English, the linguist argues, consonant +consonant (CC) combinations in initial position are very normal. To these possibilities, one has to add the fact of having an [s] as the first consonant and a plosive as the second (only voiceless -p, t, k-, not voiced b, d , g). For examples, St + vocal as instress, stand. Sk + vocal as in squint, skull.

2.1.7.6 English Stress

According to Reima (1989), English has the following stress rules:

2. A number of words have two different stress patterns according to whether

they are verbs or nouns, e.g., absent, accent, conduct, convict, digest,

separate, perfect, permit, present, suspect, transport.

3. When a suffix is added to a word, the new form is stressed on the syllable as was the basic word, e.g.,

a’bandon a’bandonment

‘happy ‘happiness

‘reason ‘reasonable

4. Words ending in {-tion, -sion, -ic, -ical, -ity,} almost always have primary stress on the syllable preceding the ending, e.g.,

‘public pu’blicity

bi’ology bio’logical

con’tribute contri’bution

e’conomy eco’nomical

5. If a word ending in -ate or -ment has only two syllables, the stress falls on the last syllable if the word is a verb, but on the first syllable if the word is a noun or an adjective. When stressed, the ending is pronounced [eyt], [m] [nt]; when unstressed, it is pronounced [t],[m][n], e.g.,:

cre’ate de’bate

in’flate lo’cate

‘climate ‘senate

‘private ‘cognate

2.1.8 Contrastive Analysis

Contrastive Analysis (CA), Finegan (2004: 574) explains, is a method of analyzing languages for instructional purposes whereby a native language and a target language are compared with a view to establishing points of difference likely to cause difficulties for learners. CA can be portrayed from different aspects such as the following:

2.1.8.1. Historical Perspective

Sir William Jones is a linguist widely considered as the pioneer of a systematic language comparison. Declaring his research finding in a formal speech in 1786, he said:

“Sanskrit bears a resemblance to Greek and Latin which is too close to be due to chance, shows rather, that all the three,’have sprung from some common source which, perhaps, no longer exists and Gothic (that is, Germanic) and Celtic probably had the same origin” (Alatis, 1968). Following the historic speech, linguists all over Europe began to be involved in an open competition for researches in comparative linguistics. They wanted to find out if some languages were so similar that they could be put together under one language family. However, they started to compare and contrast languages for pedagogical purposes only much later. This new comparison and contrast for the betterment of teaching and learning a foreign language would be known as Contrastive Analysis (henceforth referred to as CA).

CA was born when descriptive-synchronic linguistics began to make a name for itself. Advancement in descriptive-synchronic linguistics is marked by the

publication of Language (Sapir, 1921) and Sound Patterns in Language (Sapir,

“I found that it was difficult or impossible to teach an Indian to make phonetic distinctions that did not correspond to ‘points in the pattern of his language’ however these differences might strike our objective ear, but that subtle, barely audible, phonetic differences, if only they hit the ‘points in the pattern’ were easily and voluntarily expressed in writing.” (p. 62)

In Sound Patterns in Language (1925), Sapir explains that the habits of a native speaker are part of a system which is orderly organized. He also underlines the importance of phonemes (points in the pattern) which are different from phones (phonetic entities). Sapir’s view paved the way for the introduction of structural linguistics.

Fries brought Sapir’s views into his classroom activities, paying special attention to his students’ mistakes, both in pronunciation and in writing. After a series of observations, he came to a conclusion that a certain group of students had a tendency to make similar mistakes. He noticed that the students who spoke Spanish, for example, could not pronounce certain English words correctly. They pronounced speak as [espik], study as [estadi] and school as [eskul]. Students from the Philippines also made mistakes, but they showed different patterns. They pronounced the three words above by inserting [e] between the consonant sequence. Thus, speak became [sepik],study became [setadi] and school became [sekul]. Then, Fries related ‘the patterns of mistakes of his students’ to the ‘points in the pattern’ of Sapir. The result is an idea which gave birth to the so-called contrastive analysis.

2.1.8.2 Purposes of CA

whereas Contrastive Analysis endeavors to discover similarities and differences between the first language (L1) and the second language (L2) for the improvement of teaching and learning of a foreign language.

In 1945, Fries, who is recognized as the father of CA, in his bookTeaching

and Learning English as a Foreign Languageemphasized :

The most efficient materials grow out of a scientific descriptive analysis of the language to be learned carefully compared with a parallel descriptive analysis of the native languages of the learner. Only a comparison of this kind will reveal the fundamental trouble spots that demand special exercises and will separate the basically important features from a bewildering mass of linguistic details (p.2).

Almost twelve years later, Robert Lado, one of Fries’ prominent followers, proposed a similar view in his book,Linguistics Across Cultures (1957), saying:

“The most important new thing in the preparation of teaching materials is the comparison of native and foreign language and culture in order to find the hurdles that really have to be surmounted in the teaching ( p. 3) Fries and Lado made CA very popular in the 1950-s and 1960-s. The popularity tempted CA proponents to put forth several claims, some of which are considered overambitious such as the following:

1. mistakes of a learner are primarily due to interference from L1. 2. similar points in L1 and L2 do not cause problems for a learner. 3. different points in L1 and L2 cause serious problems for a learner.

4. different points in L1 and L2 are detected from a comparison of L1 and L2. 5. results of the comparison form the basis on which difficulties are predicted. 6. materials designed on the basis of the comparison of L1 and L2 are useful.

2.1.8.3 Movement Against Contrastive Analysis

Linguists such as Richards, Selinker, and W. R. Lee question the usefulness, necessity, and relevance of CA. Lee, later editor ofEnglish Language Teaching

(1970), writes:

“Now it is often said that by means of a thorough comparison of the native language and the foreign language we can predict the learning errors. But is it true? And if it is true, is such a prediction necessary? And can the comparison be thorough?” ( p.4)

Furthermore, Lee argues:

“Prediction is by no means wholly reliable. Although there are common faults, not all speakers of the same first language cope with the difficulties of learning of a particular foreign language in the same way, making exactly the same mistakes”. (p. 5)

L. A. Hill, a British language scholar who was popular with English teachers in South East Asia in the 1970-s, also discredits the value of CA when he said, “Most of the students’ errors in learning English are caused by the conflict between the patterns within the English language itself.”

On the whole, those critics agree with CA proponents that there is interference from L1. However, they refuse the idea that L1 is the primary source. They explain that there are some other important factors behind the difficulties of a foreign language learner. W. R. Lee states “but it is not only the learner’s native language which exercises this influence. There is interference both from L1 and at every stage from what has already been taught and absorbed.” (Alatis: 186)

“...it seems to me that in relation to L2 teaching, the most important role of contrastive analysis - or rather, of the data obtained by contrastive analysis - is explanatory rather than predictive (p. 159).

Catford is certainly pleased to see CA practitioners design a lot of theories on language teaching and learning. However, he deems it more important for them to go into the field and collect data about students’ mistakes and arrange them into types, exactly like what practitioners of Error Analysis (EA) do. By combining CA and EA, he argues, a language analyst can explain more clearly why certain students make certain mistakes.

2.1.8.4 In Defence of Contrastive Analysis

The controversy above indicates that contrastive analysts and their critics differ mostly about two basic claims of Contrastive Analysis (CA). The first is the claim of CA that the native language interference is the major cause of difficulty in a second language learning. The second is that CA can predict difficulties in the learning of a second language.

In an effort to tackle the first issue, it is well to consider what CA was really like in the early stage of its development in the 1950-s. Back then, Fries and Lado, the two founders of CA, directed their searching light mostly to the phonological errors of their students. They turned out to be fairly successful and quickly made a name for themselves. However, problems appeared as soon as their ambitious followers began to include syntactic and semantic errors in their analysis. In other words, every language scholar seemed to agree in the early days of CA that the native language interference in learning the phonology (also popularly known as

“The learner transfers the sound system of his native language and uses it instead of that of the foreign language without fully realizing it. This transfer occurs even when the learner consciously attempts to avoid it. Force of habit influences his hearing as well as his speaking. He does not hear through the sound system of the target language but filters what reaches his ears through his own sound system.”

(Language Teaching, 1965: 72).

Present-day language scholars also see clear signs of the first language interference in learning the phonology of a second language. M.F Baradja, a staunch advocate of CA, argues that “unless the learner is very young, nobody can deny that there is interference of the mother tongue in the acquisition of the phonology of a foreign language. The fact that an Indian speaks English with an Indian accent, a Japanese speaks English with a Japanese accent, etc., is a definite proof of the existence of the native language interference” (1971: 4). Jack Richards (2002) agrees when he asserts “that very few learners are able to speak a second language without showing evidence of the transfer of pronunciation features of their native tongue”.

In fact, even those scholars who are critical of CA generally agree that there is interference from the mother tongue (L1). What they refuse is the claim that L1 is the primary source of interference. W. R. Lee states… “but it is not only the learner’s native language which exercises the influence. There is interference both from L1 and at every stage from what has already been taught and absorbed.” (Alatis, 1970: 186)

thing is certain, they have finally admitted, that both L1 and L2 are important potential sources of difficulty (1971: 5).

Now comes the issue of prediction. Proponents of CA generally complain that critics of CA misunderstand the meaning of ‘ to predict’ in contrastive analysis. Therefore, staunch advocates of CA such as Baradja consider it necessary to explain that ‘topredict’ means no more than ‘to show with some explanationwhat, where, and whycertain areas in the target language are likely to be potential trouble spots for a learner. To predict, Baradja ascertains, is not intended to mean ‘to show with certainty’. Thus, in making a prediction, it is always possible that an analyst can anytime make a mistake. Fortunately, the Indonesian linguist and English teacher adds, a linguistic science has made so much progress that it can nowadays help a contrastive analyst to attend to the phonological problems more effectively.

The brief discussion above may have made it clear that CA is still useful and relevant in a foreign language teaching. This is precisely the reason why the present writer insists on conducting a CA of English and Nataia phonology in spite of the controversy.

2.2 Review of Related Studies