www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Do female broiler breeder fowl display a preference

for broiler breeder or laying strain males in a

Y-maze test?

Suzanne T. Millman, Ian J.H. Duncan

)Col. K.L. Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare, Department of Animal and Poultry Science, UniÕersity of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1

Accepted 1 April 2000

Abstract

In recent years, the commercial broiler breeder industry has reported problems of male

w

aggression towards females Millman, S.T., 1999. An investigation into extreme aggressiveness of

x

broiler breeder males. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Guelph . Although this aggression

w

is shown by the males and is apparently a defect in their behaviour Millman, S.T., Duncan, I.J.H., 2000. Strain differences in aggressiveness of male domestic fowl in response to a male model.

x

Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 66, pp. 217–233 , it is also possible that it stems in some way from the females. For example, broiler breeder females may not be receptive to male courtship advances, and may avoid males, thus causing frustration in otherwise normal males. The objective of this study was to examine mate preference by broiler breeder females and the effects of sexual experience on preference. A total of 24 mature, broiler breeder females were individually tested in a Y-maze, with females choosing between a broiler breeder male and a laying strain male. Females were tested using male models and tethered live males, both when the females were sexually inexperienced and after they had been housed with broiler breeder or laying strain males for 6 weeks.

Females did not display a male-strain preference when tested with models, but sexually experienced females displayed some evidence of a preference for laying strain males in tests with

Ž .

live males, which did not reach statistical significance P-0.10 . Live males were a stronger

Ž .

attractant for sexually experienced females than were models P-0.005 . Individual females tested with the same pair of males showed different preferences, suggesting females used male behaviour as a basis for their choices, and not male morphology.

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q1-519-824-4120 ext. 3652; fax:q1-519-836-9873.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] I.J.H. Duncan .

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

In conclusion, we found no evidence that broiler breeder females inherently discriminate against broiler breeder males.q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Broiler breeder; Mate choice; Genetics; Sexual behaviour; Chickens

1. Introduction

In this study, we were interested in investigating if broiler breeder females display an inherent male-strain preference and how this preference might be affected by sexual experience.

The commercial broiler breeder industry has reported problems of male aggression

Ž .

towards females in recent years Mench, 1993 . Outbreaks of severe male aggression occur sporadically and causal factors remain elusive. Producers report that aggression is particularly common when males are mixed with sexually underdeveloped females

ŽMillman, 1999 . When males are extremely aggressive, broiler breeder females remain.

on raised slatted areas in the barn and are therefore less accessible to males. Since females often have lacerations on the back of the head or along the torso, it is likely that they learn to remain on the slats to avoid injury. However, it is also possible that avoidance by females precedes injury and male aggression results from frustration. It may even be that problems of male aggression arise in response to low sexual receptivity of broiler breeder females.

Our previous research suggests that broiler breeder females display sufficient levels of sexual motivation to allow full sexual intercourse, particularly when housed with

Ž .

laying strain males Millman et al., 1996 . Broiler breeder females housed with laying strain males had significantly higher fertility than females housed with broiler breeder males, and females responded to displaying laying strain males by approaching them more frequently than broiler breeder males. Broiler breeder males displayed less courtship behaviour and performed more forced copulations than did commercial laying

Ž .

strain males. For further discussion of this point, see Millman 1999 . It is not clear if differences in females approaching males resulted from the effectiveness of courtship displays by laying strain males, or because females found laying strain males inherently

Ž .

more attractive. Kruijt 1964 found that junglefowl males could learn to change their courtship displays. Frequency of one courtship element, such as waltzing, could be increased by reinforcement with access to a female. When a different element, such as cornering, was reinforced, males decreased frequency of waltzing and increased corner-ing. If females in our study found laying strain males more attractive, they may have been more attentive to the courtship displays of these males. Consequently, courtship displays by laying strain males may have been reinforced more frequently than displays by broiler breeder males.

The preference by females for males of one strain over another could result from

differences in the physical conformation andror the behaviour of males. Previous

research indicates that female domestic fowl prefer same-strain males based on differ-Ž

ences in morphology rather than courtship behaviour Lill, 1968b; Lill and Wood-Gush, .

altered through selection for meat traits, with massive muscle development particularly in the breast.

Although some studies found male displays to be important in mate choice by Ž

females Zuk et al., 1992, 1995; Collins, 1994; Chappell et al., 1997; Leonard and

. Ž

Zanette, 1998 , others did not Lill and Wood-Gush, 1965; Zuk et al, 1990c; Ligon and .

Zwartjes, 1995; van Kampen, 1994 . In our previous study, broiler breeder strain males

Ž .

performed less courtship behaviour than laying strain males Millman et al., 1996 . It is also possible that limitations of conformation may make courtship displays by broiler breeder males less effective in releasing female sexual motivation than displays by laying strain males.

The objectives of this study were to tease apart mechanisms of female mate

Ž . Ž .

preference involving 1 male physical characteristics and 2 male behaviour. We also wanted to determine if sexual experience would affect mate preferences by females. Our hypothesis was that females would discriminate against broiler breeder males.

2. Materials and methods

Procedures carried out in this experiment were approved by the University of Guelph Animal Care Committee, according to the guidelines of the Canadian Council for Animal Care.

2.1. Treatments

This experiment was conducted as a repeated measures design with two treatments.

Ž .

Broiler breeder females Arbor Acres were individually placed in a Y-maze to test mate preferences. In the first test, females chose between male models of a broiler breeder

Ž . Ž .

strain Ross and a commercial laying strain ISA Brown . Broiler breeder males had white plumage and laying strain males had buff plumage with some dark brown feathers. In the second test, models were exchanged for a tethered live male of each strain. Females were tested when mature, but sexually inexperienced, and again after they had been housed with males for 6 weeks.

2.2. Birds

Ž .

Hens used in this experiment were mature broiler breeder females Arbor Acres , that had had no physical or visual experience with males. They had been reared in single-sex

Ž

groups of 20–30 individuals according to management guidelines Arbor Acres Farms, .

1995 . At maturity, they were housed in eight 3.35=3.35 m pens of 30 individuals,

with nest boxes and pine shavings for litter. Visual access between pens was restricted by plywood partitions, since pairs of males were to be housed with these females in these pens between Inexperienced and Experienced Tests. A standard laying ration

ŽLeeson and Summers, 1991. was provided daily at 0900 h, with feed restricted

Ž .

according to management guidelines Arbor Acres Farms, 1995 . Target weights were Ž .

achieved, with mean body weight "S.E. for hens being 3.9"0.1 kg just before

16L:8D lighting regimen was provided, with lights on at 0500 h and off at 2100 h. Hens were 48 weeks of age when testing began and were 57 weeks of age when testing concluded. Birds had been wing-banded at 1 week of age for individual identification and three females from each of eight pens were used in the preference tests.

The males used in this experiment had been reared in single-sex groups of 20–30 Ž .

individuals. The broiler breeder males Ross had been reared and maintained with feed

Ž .

restricted according to the management guidelines Ross Breeders, 1997 . The laying

Ž .

strain males ISA Brown had also been reared with feed restricted to give a propor-tional body weight reduction equivalent to the reduction experienced by the broiler Ž . breeder males. Further details on rearing may be found in Millman and Duncan 2000 .

Males were individually housed at sexual maturity in pens with visual, but no physical access between pens. Males of each strain were housed in separate rooms, with

pens for laying strain males measuring 1.8=1.2 m and pens for broiler breeder males

measuring 1.5=1.5 m. All pens had pine shavings as litter. Males had been used in

Ž .

previous experiments Millman and Duncan, 2000 involving behavioural observations and blood sampling. As a result, males were familiar with being handled and had received limited sexual experience. Broiler breeder males were feed-restricted according

Ž .

to management guidelines Ross Breeders, 1997 . Laying strain males were feed-re-stricted to give a proportional body weight reduction equivalent to the reduction that should have been experienced by the broiler breeder males. We were able to achieve the target body weights for the laying strain males, but were less successful in restricting the body weights of our broiler breeder males. Although they were maintained on the recommended growth curve when group-housed during the rearing phase, broiler breeder males gained weight when they were moved into individual pens. This was likely due to large variation in body weights during rearing of broiler breeder males, which did not occur with feed-restricted laying strain males. Thus, when individually housed, underweight broiler breeder males grew, whereas overweight males did not lose weight. Mean body weight of broiler breeder males when testing began at 39 weeks of age was 5.4 kg, which was 25% above the recommended body weight at that age and

Ž .

similar to the body weight of ad libitum fed males Millman, 1999 . Conversely, laying strain males weighed 2.3 kg at 39 weeks of age when testing began, which was 82% of

Ž .

the body weight of ad libitum fed laying strain males Millman, 1999 . This trend persisted through the experiment and at 57 weeks of age when testing concluded, body weights were 5.8 kg and 2.6 kg for broiler breeder and laying strain males, respectively.

2.3. Male models

Male models were developed according to the method described by Millman and Ž .

Duncan 2000 . Two mature males of each strain were euthanized and each male was suspended in a sling from dowling rods. Prior to rigor mortis, limbs and head of each male were adjusted, in the manner of a marionette, into a non-threatening, standing posture and eyes were closed to avoid possible effects of freezing on eyeball structure. Models were placed in a freezer for 24 h, after which time strings and sling were

Ž removed. Once frozen, models were able to stand alone, without supporting rods Fig.

.

Fig. 1. As viewed by the female from the starting box, a broiler breeder strain male model is on the right and a laying strain male model is on the left.

frosting up of comb and wattles occurred immediately after removal from the freezer, tests were not initiated until 5–10 min had passed, by which time these fleshy appendages thawed enough to appear reddish-pink and life-like. Half of the females

Ž .

tested per day were exposed to one pair of models Pair A , after which models were returned to the freezer and the remaining females were tested with the other pair of

Ž . models Pair B .

2.4. Testing procedure

Tests were conducted from 1700 to 2100 h, as sexual behaviour has been shown to be

Ž .

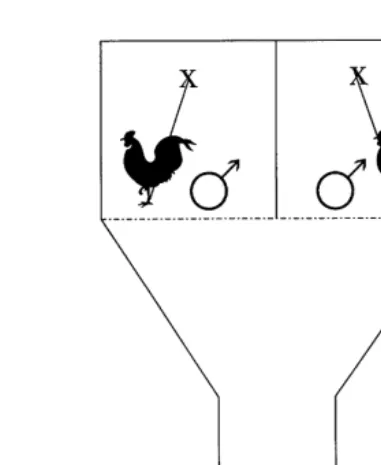

most frequent late in the day Lake and Wood-Gush, 1956 . Three females in each of eight home-pens were tested. Four females were tested per day and randomized so that females from the same home-pen were not tested on the same day. Each female was first tested with male models, after which models were replaced with live, tethered males. Ž . Male strains were randomly assigned to compartment A or B of the Y-maze Fig. 2 , balanced across females, and each female was presented with male strains in the same compartments in all tests. Similarly, each female was always allowed to choose between the same individual live males and models in all tests. Live males were only used in one test per day and were always presented as the same pair of individuals, so that Laying strain male 1 was always paired with Broiler Breeder strain male 1. Eight males of each strain were used, with each male pair used in tests with three females from different home-pens.

Fig. 2. Schematic diagram of the Y-maze used during preference tests. Solid lines represent wooden partitions. Dashed line represents the marker, delineating compartment of each male. Dotted line represents the gate, releasing female from the starting box.

while models were placed in the Y-maze. Models were placed centrally over the rings, which secured the tether in the live male tests and were oriented to face the start box. The plywood partition was removed allowing the female to observe the models for 2 min, after which the starting gate was raised by the observer hidden behind the female. Following testing with male models, the female was caught, returned to the start box and the wooden partition replaced to obscure her view of the compartments. Male models were replaced with live males. Live males were gently carried in an upright position from their home-pens and were secured to tethers using black Velcro leg-bands. As compartments were separated by a wooden barrier, males were not able to see each other during the test. Care was taken to obscure visual contact between males when placing them in the compartments and after both males were tethered, 1 min was allowed for males to acclimitize to the environment before the wooden partition was removed, exposing them to the test female. The female was able to observe the males for 2 min and then the starting gate was raised to release her.

Direct observations were taken with the observer behind a wooden partition, for 5 min during tests with male models and for 15 min in tests with live males. A female was

considered in residence with a male when she entered the 1=1-m compartment in

crouching, prior to courtship displays by the male. A copulation was defined as the male mounting, gripping and treading the female and appearing to achieve cloacal contact.

In an attempt to decrease the confounding variable of fearfulness during testing, birds were acclimatized to the test conditions. At 1 week prior to testing, males were individually released in the test pen for 30 min. The following day, males were tethered for 15 min in each side of the Y-maze. Males had been handled frequently in previous experiments and displayed little fearfulness or alarm in the test surroundings. They explored the test pen thoroughly and spent the remainder of the time foraging. Crowing and wing-flapping were often performed as males could hear, but not see, males in other rooms of the barn. The males adjusted to tethers rapidly and they rarely pulled against the tether.

Females were less accustomed to being handled than the males and had no experience outside their home-pen. A trial run of the test, using surplus birds, indicated that females remained tonic in the starting box and were extremely fearful. Hence, the three test females from each home-pen were placed together in the start box and released simultaneously into the Y-maze for 30 min. The presence of social companions successfully facilitated exploratory behaviour and appeared to reduce fearfulness in the females. The following day, the procedure was repeated for females individually and again during the morning of the day they were tested.

After all females had been tested once with models and live males, pairs of broiler breeder or laying strain males were randomly placed in each of the female home-pens. As males have been shown to maintain social relationships with only visual and auditory

Ž .

contact Mench and Ottinger, 1991 , we paired males with their immediate neighbour in an attempt to decrease fighting. Females were not housed with the individual males they were exposed to during preference tests. Males were fed from raised hoppers to maintain feed-restriction and female feeders contained male exclusion grills. Although the head width of laying strain males was small enough to pass through the exclusion grill, no males in this experiment had their combs dubbed and large combs restricted access to the female feeder. After 6 weeks, males were returned to their individual pens. Preference testing commenced 2 weeks later, with birds familiarized to the test pen during the morning of the day they were tested.

Two weeks following testing, all males were euthanized. Males were weighed and comb length was measured immediately by placing the comb on a ruler, laterally and recording the distance from the front tip to the back tip, in millimeters. Males were autopsied and examined for evidence of abnormalities, such as deep pectoral myopathy and abnormalities of the hock cartilage, which might impede movement or be suggestive of pain.

2.5. Data analysis

Ž .

a Chi-Squared Goodness-of-Fit test Zar, 1984 . Since we could not be sure of the motivation of females preferring neither strain, results were further examined with females choosing neither strain removed from the analysis to determine male strain bias among the females that made a choice.

3. Results

3.1. Females approaches to males

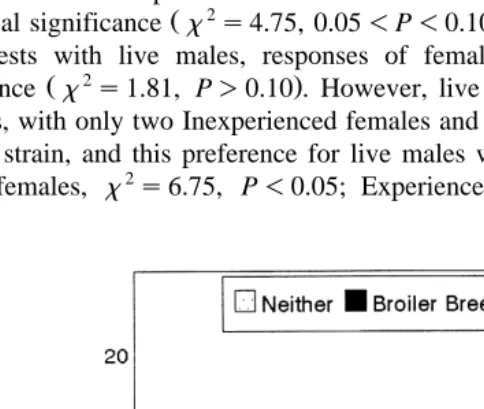

Our first measure of mate preference was based on which male the female ap-proached first, with the assumption females would approach the most attractive male first. Females approached models cautiously and some females crouched and allopecked the comb and wattles of the model when in close proximity. Hence, females appeared to react to models as if they were actual males and not simply novel objects. The number of Inexperienced females choosing broiler breeder strain, laying strain and neither strain,

Ž 2 .

did not differ significantly Fig. 3, x s0.25, P)0.10 . There was no difference in

Ž 2 .

female responses after receiving sexual experience x s4.47, P)0.10 . Although a

greater number of Experienced females chose neither strain, this difference did not reach

Ž 2 .

statistical significance x s4.75, 0.05-P-0.10 .

In tests with live males, responses of females were also unaffected by sexual

Ž 2 .

experience x s1.81, P)0.10 . However, live males were a stronger attractant for

females, with only two Inexperienced females and one Experienced female approaching Ž

neither strain, and this preference for live males was statistically significant

Inexperi-2 2 .

enced females, x s6.75, P-0.05; Experienced females, x s12.25, P-0.005 .

Fig. 3. Number of females preferring male models and tethered live males. Statistical significance according to

Ž .

When females preferring neither strain were removed from the analysis, there was no strain preference among Inexperienced females that made a choice, and although twice as many Experienced females chose laying strain males than broiler breeder strain

Ž 2 .

males, this did not reach statistical significance x s3.67, 0.05-P-0.10 . We

assumed females would first approach the most attractive male, but it is likely that females approached males for a variety of reasons. Some females displayed strong sexual motivation, adopting a sexual crouch, giving food-type calls and allopecking the male’s comb or wattles. Other females appeared to be exploring and seemed quite oblivious to the males. No preference for left or right arms of the Y-maze was displayed by either Inexperienced or Experienced females during testing with male models or live males. Hence, although there was some suggestion that Experienced females were more discriminating and may have some preference for live laying strain males, there was little evidence of an inherent mate preference based on female approach.

3.2. Females interactions with males

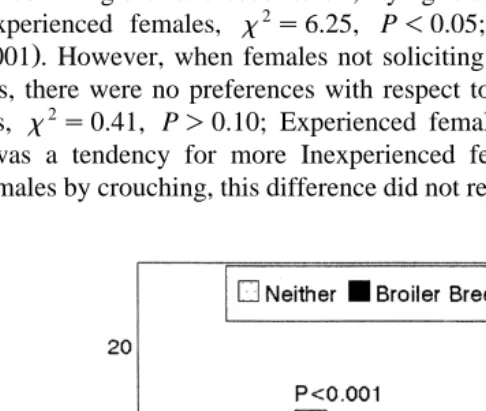

The second measure of preference was based on the interactions of females with males during live male tests. There were significant differences between the number of

Ž females soliciting broiler breeder strain, laying strain and not soliciting either strain Fig.

4, Inexperienced females, x2s6.25, P-0.05; Experienced females, x2s15.25,

.

P-0.001 . However, when females not soliciting either strain were removed from the

Ž

analysis, there were no preferences with respect to male strain solicited Inexperienced

2 2 .

females, x s0.41, P)0.10; Experienced females, x s0.14, P)0.10 . Although

there was a tendency for more Inexperienced females than Experienced females to Ž 2

solicit males by crouching, this difference did not reach statistical significance x s7.0,

Fig. 4. Number of females soliciting and copulating with tethered males during preference test. Statistical

Ž .

.

0.05-P-0.10 . Not all males responded sexually to females, even when presented

with a strong sexual crouch. It was not clear if failure to respond resulted from distraction by the other male in the maze, lack of libido, or male mate preferences. Conversely, several females copulated two or three times during a single test. Two females copulated with both strains of male during the test and in both cases, females copulated with the laying strain male first. However, as preference was unclear, these observations were discarded from the analysis. There were significant differences among the number of females copulating with broiler breeder strain, laying strain and not

Ž 2

copulating with either strain Inexperienced females, x s9.5, P-0.01; Experienced

2 .

females, x s12.75, P-0.005 . However, no strain preference was detected within

Ž 2

females that copulated Inexperienced females x s1.6, P)0.10; Experienced

fe-2 .

males, x s1.0, P)0.10 . Hence, based on interactions of females with males, there

Ž .

was no evidence to support the notion of preferences or avoidances of particular strains of male.

3.3. Females proximities to males

For our third measure of preference, we considered time spent in residence with live Ž .

males Fig. 5 . Each 15-min test was divided into 30-s periods, so that females could spend a maximum of 30 time periods in each compartment of the maze, resident with broiler breeder strain, laying strain or neither strain. Because females could move freely between compartments, they could spend time in each of the compartments during one 30-s period and thus, the sum of the time periods for the three locations could be more than 30. When the number of time periods that the females spent in each compartment were compared, time periods spent with broiler breeder strain and laying strain males

Ž 2

did not differ Inexperienced females, x s2.47, P)0.10; Experienced females,

Fig. 5. Mean number of 30-s time periods females spent in residence with tethered live males. Statistical

Ž .

2 .

x s0.47, P)0.10 . However, data were highly variable, as some females spent all of

the available time with one male and other females moved actively throughout the maze. Sexual experience did not seem to affect motivation of females to be in close proximity to males, since approximately twice as much time was spent in residence with neither

Ž 2

strain compared with either of the males by both Inexperienced females x s25.0,

. Ž 2 .

P-0.001 and Experienced females x s27.3, P-0.001 . Hence, there was no

evidence of a male strain preference based on the number of time periods females spent with males.

3.4. IndiÕidualÕariation

We saw some evidence that certain individual males were attractive to females. For example, Laying strain male 1 was chosen in all six tests in which he was used. Furthermore, in five tests, females approached Laying strain male 1 within 2 min of being released from the starting box. In four tests, females spent 93% to 100% of time periods in residence with Laying strain male 1, and females solicited and copulated with Laying strain male 1 during four of the six tests. Of the 10 females that chose the same male during Inexperienced and Experienced trials, seven preferred the laying strain male. Although Laying strain male 1 was preferred by all three females he was presented to, results involving other pairs of males were inconclusive. One female consistently preferred Broiler Breeder strain male 8, while another female consistently preferred Laying strain male 8 and the same situation was observed with Pair 9. It is difficult to know if these differences arose randomly from chance or whether they reflected distinct differences in the preferences of individual females.

3.5. Physical differences between males

Since there was no consistency in the preferences by females regarding the males presented, male morphological traits must not have been of great importance in female choice. Comb size of broiler breeder strain males ranged from 67.5 to 97.5 mm, with a mean of 73.0 mm and laying strain males had combs ranging in size from 67.5 to 75.0 mm, with a mean of 70.0 mm. In all pairs, broiler breeder strain males had larger combs, wattles and shanks than did laying strain males. Health status of the males also did not appear to affect females’ choice. When males were autopsied 2 weeks following this study, we found that four broiler breeder strain males were afflicted with deep pectoral myopathy and each of these males was chosen by at least one female. It is difficult to know whether these males had been affected during the testing of Inexperienced females, and although two of the males were rejected by all three Experienced females to which they were presented, two of them were chosen by two of three Experienced females to which they were presented.

4. Discussion

Ž .

proven elusive Duncan and Hughes, 1988 . Females associate with males for a variety of reasons, of which mating is only one. For example, as a result of being handled and removed from their flock mates, females may have been fearful and may have approached males for social companionship or protection. However, a male-strain preference, regardless of motivation, would likely be correlated with mate choice and some individual females displayed evidence of strong sexual motivation during testing. Although we did not compare broiler breeder females with laying strain females, there was no evidence that broiler breeder females have unusually low levels of sexual motivation, inherently or because of competing motivations, such as hunger. They readily approached and solicited copulations from males. Although it is possible that commercial management practices may occasionally result in mixing of females that are less sexually mature than males, and therefore less sexually receptive, this cannot account for problems of hyper-aggressiveness by male broiler breeder fowl.

Ž .

Although Ligon and Zwartjes 1995 found that female junglefowl did not display a preference for males based on feather colour, this trait has been shown to be important

Ž

in own-strain recognition of domestic fowl Lill, 1968a,b; Marler et al., 1986; Evans and .

Marler, 1992 . Female domestic fowl display preferences for males of their own strain which are rooted in male morphology rather than in differences in male courtship

Ž .

displays Lill and Wood-Gush, 1965; Borowicz and Graves, 1986 . However, own-strain bias of females is affected by rearing conditions. When females are reared with

Ž .

other-strain males, they crouch for both other-strain and own-strain males Lill, 1968b . In our experiment, females had no experience with males, but were reared with same-strain females. This may have resulted in a bias by females for broiler breeder strain males, which were similar in colour and size to females, relative to the laying strain males, which had buff and brown-coloured feathers and lighter body weight. Same-strain bias has been found to affect the sexual behaviour of male chickens, such that males court own-strain females more than other-strain, regardless of rearing

Ž .

experience Lill, 1968a; Marler et al., 1986; Evans and Marler, 1992 . Hence, in our study, the broiler breeder females may have acted as a stronger stimulus for courtship of broiler breeder strain males than laying strain males. As females did not prefer broiler breeder strain males, either own-strain bias was not a factor in our experiment or laying strain males were able to overcome this bias and were as attractive, or possibly even more attractive to females than were broiler breeder strain males.

Studies on junglefowl, the putative progenitor of domestic fowl, suggest that traits, such as comb size or colour and iris colour which may give some indication of health or

Ž

condition, are important factors of mate choice by females of this species Zuk et al., . 1990a,b, 1995; Ligon and Zwartjes, 1995; Ligon et al., 1998; Chappell et al., 1997 . Since both male and female junglefowl infected with an intestinal parasite had smaller and paler combs, traits such as comb length, comb colour and iris colour may reflect

Ž .

traits. We found little evidence that our females were able to detect male health status, since unhealthy males were chosen by females, both prior to and following experience with males.

Ž .

Leonard and Zanette 1998 found that comb size and colour did not significantly correlate with mate choice of White Leghorn females. However, von Schantz et al.

Ž1995 found that White Leghorn females preferred males with larger combs. It is not.

clear whether these discrepant results reflect genetic differences between the stocks used Ž .

or differences in experimental methods. Graves et al. 1985 found that although female domestic fowl preferred to approach unfamiliar males that had large combs, when presented with familiar males, females preferred dominant males independently of comb

Ž

size. It is known that dominance status positively correlates with comb size Siegel and .

Dudley, 1963 . Hence, the importance of comb traits in other mate choice studies may be a reflection of male dominance status and not a preference for comb size per se. This could also explain why variability has been observed in results. In addition to physical and physiological traits, social rank is highly dependent on experience. Since pairs of males were housed with females between Inexperienced and Experienced female trials, dominance status of males may have changed during the course of the experiment and a male perceiving himself to be a dominant individual during testing of Inexperienced females may have become subordinate by the time he was used during testing of the Experienced females. However, this type of change was unlikely to occur within trials of Inexperienced or Experienced females.

We did not analyse male behaviour during the preference tests, as we expected it to be confounded with female proximity. However, in our previous research, we found that broiler breeder males performed significantly less courtship behaviour than laying strain

Ž .

males Millman et al., 1996 . The males used in the current experiment were also previously observed interacting individually with groups of three broiler breeder fe-males. During these observations, laying strain males performed significantly more copulations than broiler breeder strain males and received more allopreening by females ŽMillman, 1999 . Conversely, broiler breeder strain males chased females, and females. struggled more frequently during mating attempts of broiler breeder strain males. Hence, it seemed reasonable to assume that during the current study, broiler breeder strain males would perform less courtship during the preference test than laying strain males and would be more likely to chase the female.

Information on the importance of male courtship on mate preference by female fowl Ž is ambiguous. Display rates of unsuccessful male junglefowl tend to increase Lill and

.

Wood-Gush, 1965 and female junglefowl crouch more frequently for displaying males

ŽLill, 1966 . Zuk et al. 1990b, 1992 found display rate of males to be of little. Ž .

importance in preferences by female junglefowl, but in a later study, display rate was Ž correlated with condition-dependent morphological traits preferred by females Zuk

.

et al., 1995 . Some of the discrepancy of findings between experiments may arise from grouping all display elements into one category, since courtship elements vary in their

Ž .

potency to attract females Wood-Gush, 1954 .

if this non-significant statistical trend reflects a true preference by Experienced females. The sexual experience gained by the females, while living with males between the trials, may have altered their preference. However, it is also possible that the experience gained by the stimulus males, while living with females between the trials, might have altered their behaviour so that they were not giving the same signals in the second trial as in the first. This might have been responsible for the trend in female preference. For example, it is known that frequencies of occurrence of elements of male courtship can

Ž .

be altered by conditioning procedures Kruijt, 1964; van Kampen, 1997 . It is possible in our study that during the inter-trial period, laying strain males learned quickly to adjust their courtship patterns and displays so that they were very effective in gaining the attention of females. The broiler breeder males, on the other hand, may have been slow learners and may not have adjusted their courtship and displays. This would result in the stimulus quality of the laying strain males being higher in the second test than in the first and might account for the trend for them to be preferred.

Some of the inconsistencies in the results from this study may also have been due to males behaving differently towards different females. It is known that males show mate preferences and will court some individual females more than others within a flock ŽWood-Gush, 1956; Blohowiak et al., 1980 . Thus, the fact that with a particular pair of. males, some females preferred one and some preferred the other, may have been due to

Ž

the male having a special attraction to certain females and acting differently by either .

emitting subtle signals or more obvious elements of courtship behaviour towards those females.

Finally, this experiment was performed as one part of a larger project investigating aggression towards females by broiler breeder males. As a strong male strain preference by females was not evident from our observations, we can assume that avoidance of males by female broiler breeder fowl results from learning and not innate aversion. There was nothing in the morphology or behaviour of broiler breeder males that caused females to avoid them completely. However, females were less likely to associate with broiler breeder males after they had received experience with males. Behaviour of both males and females may differ in commercial conditions as a result of social or environmental factors and the importance of social elements affecting aggressiveness by broiler breeder males has yet to be determined.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the technical assistance we received for this project from the staff at the OMAFRA Arkell Poultry Research Station. We would also like to thank Dr. Tina M. Widowski for her helpful advice. Funding for this project was provided by an NSERC operating grant to Dr. Ian J.H. Duncan.

References

Arbor Acres Farms, 1995. Arbor Acres FSY Management Manual. Glastonbury, CT, USA.

Borowicz, V.A., Graves, H.B., 1986. Social preferences of domestic hens for domestic vs. junglefowl males and females. Behav. Processes 12, 125–134.

Chappell, M.A., Zuk, M., Johnsen, T.S., Kwan, T.H., 1997. Mate choice and aerobic capacity in red junglefowl. Behaviour 134, 511–529.

Collins, S.A., 1994. Male displays: cause or effect of female preference? Anim. Behav. 48, 371–375.

Ž .

Duncan, I.J.H., Hughes, B.O., 1988. Can the welfare needs of poultry be measured? In: Hardcastle, J. Ed. , Science and the Poultry Industry. Agricultural and Food Research Council, London, pp. 24–25. Evans, C.S., Marler, P., 1992. Female appearance as a factor in the responsiveness of male chickens during

anti-predator behaviour and courtship. Anim. Behav. 43, 137–145.

Graves, H.B., Hable, C.P., Jenkins, T.H., 1985. Sexual selection in Gallus: effects of morphology and dominance on female spatial behavior. Behav. Processes 11, 189–197.

Hardesty, M., 1931. The structural basis for the response of the comb of the brown Leghorn fowl to the sex hormones. Am. J. Anat. 42, 277–323.

Ž .

Harding, C.F., 1983. Hormonal influences on avian aggressive behaviour. In: Svare, B.B. Ed. , Hormones and Aggressive Behaviour. Plenum, New York, pp. 435–467.

Harding, C.F., 1986. The importance of androgen metabolism in the regulation of reproductive behavior in the avian male. Poult. Sci. 65, 2344–2351.

Ž .

Kruijt, J.P., 1964. Ontogeny of social behaviour in Burmese red junglefowl Gallus gallus spadiceus .

Behaviour Suppl. XII, 1–201.

Lake, P.E., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1956. Diurnal rhythms in semen yields and mating behaviour in the domestic cocks. Nature 178, 853.

Leeson, S., Summers, J.D., 1991. Commercial Poultry Nutrition. University Books, Guelph, Ont., Canada. Leonard, M.L., Zanette, L., 1998. Female mate choice and male behaviour in domestic fowl. Anim. Behav. 56,

1099–1105.

Ligon, J.D., Zwartjes, P.W., 1995. Ornate plumage of male red junglefowl does not influence mate choice by females. Anim. Behav. 49, 117–125.

Ligon, J.D., Kimball, R., Merola-Zwartjes, M., 1998. Mate choice by female red junglefowl: the issues of multiple ornaments and fluctuating asymmetry. Anim. Behav. 55, 44–50.

Lill, A., 1966. Some observations on social organisation and non-random mating in captive Burmese red

Ž .

junglefowl Gallus gallus spadiceus . Behaviour 26, 228–241.

Lill, A., 1968a. An analysis of sexual isolation in the domestic fowl: 1. The basis of homogamy in males. Behaviour 30, 107–126.

Lill, A., 1968b. An analysis of sexual isolation in the domestic fowl: II. The basis of homogamy in females. Behaviour 30, 127–145.

Lill, A., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1965. Potential ethological isolating mechanisms and assortative mating in the domestic fowl. Behaviour 25, 16–44.

Marler, P., Dufty, A., Pickert, R., 1986. Vocal communication in the domestic fowl: II. Is a sender sensitive to the presence and nature of a receiver? Anim. Behav. 34, 194–198.

Mench, J.A., 1993. Problems associated with broiler breeder management. Fourth European Symposium on Poultry Welfare, 195–207.

Mench, J.A., Ottinger, M.A., 1991. Behavioral and hormonal correlates of social dominance in stable and disrupted groups of male domestic fowl. Horm. Behav. 25, 112–122.

Millman, S.T., 1999. An investigation into extreme aggressiveness of broiler breeder males. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Guelph.

Millman, S.T., Duncan, I.J.H., Widowski, T.M., 1996. Forced copulations by broiler breeder males. In:

Ž .

Duncan, I.J.H., Widowski, T.M., Haley, D.B. Eds. , Proceedings of the 30th International Congress of the International Society for Applied Ethology. Col. K.L. Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada, p. 50.

Millman, S.T., Duncan, I.J.H., 2000. Strain differences in aggressiveness of male domestic fowl in response to a male model. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 66, 217–233.

Ross Breeders, 1997. Ross Parent Stock Management Guide. Huntsville, AL, USA.

Siegel, P.B., Dudley, D.S., 1963. Comb type, behavior and body weight in chickens. Poult. Sci. 42, 516–522. van Kampen, H.S., 1994. Courtship food-calling in Burmese red junglefowl: I. The causation of female

van Kampen, H.S., 1997. Courtship food-calling in Burmese red junglefowl: II. Sexual conditioning and the role of the female. Behaviour 134, 775–787.

Von Schantz, T., Tufvesson, M., Goransson, G., Grahn, M., Wilhelmson, M., Wittzell, H., 1995. Artificial selection for increased comb size and its effects on other sexual characters and viability in Gallus

Ž .

domesticus the domestic chicken . Heredity 75, 518–529.

Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1954. The courtship of the brown leghorn cock. Br. J. Anim. Behav. 2, 95–102. Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1956. The agonistic and courtship behaviour of the brown leghorn cock. Br. J. Anim.

Behav. 4, 133–142.

Zar, J.H., 1984. Biostatistical Analysis. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Zuk, M., Johnson, K., Thornhill, R., Ligon, J.D., 1990a. Mechanisms of female choice in red junglefowl. Evolution 44, 477–485.

Zuk, M., Thornhill, R., Ligon, J.D., 1990b. Parasites and mate choice in red jungle fowl. Am. Zool. 30, 235–244.

Zuk, M., Thornhill, R., Ligon, J.D., Johnson, K., Austad, S., Ligon, S.H., Thornhill, N.W., Costin, C., 1990c. The role of male ornaments and courtship behavior in female mate choice of red jungle fowl. Am. Nat. 136, 459–473.

Zuk, M., Ligon, J.D., Thornhill, R., 1992. Effects of experimental manipulation of male secondary sex characters on female mate preferences in red jungle fowl. Anim. Behav. 44, 999–1006.

Zuk, M., Popma, S.L., Johnsen, T.S., 1995. Male courtship displays, ornaments and female mate choice in captive red jungle fowl. Behaviour 132, 821–836.