q

This research is based on work done on EPSRC grant GR/K 51105, Teamworking: building capabilities for manufacturing improvements, Prof David Tran"eld, Prof Stuart Smith and Mr. Morris Foster.

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address:d.tran"eld@cran"eld.ac.uk (D. Tran"eld)

Strategies for managing the teamworking agenda: Developing

a methodology for team-based organisation

qDavid Tran

"

eld

!,

*

, Stuart Smith

"

, Morris Foster

"

, Sarah Wilson

#

, Ivor Parry

#

!Cranxeld School of Management, Cranxeld University, Cranxeld MK 43 0AL, UK

"Centre for the Study of Change, 212 Piccadilly, London WIV 9JD, UK

#Shezeld Business School, Shezeld Hallam University, Shezeld S1 1WB, UK

Abstract

This paper reports the development of a vision driven organisation design methodology, strategic designs for teamworking (SDT), for use by senior managers in their role as organisational architects and engineers. The methodology is based upon models of teamworking. These were developed from existing theory and empirical research. SDT enables managers to design or redesign a requisite organisational form at both a conceptual and detailed level, with the aim of designing and implementing a requisite organisation to contribute to the delivery of strategic objectives. ( 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Teamworking; Manufacturing organisation; Organisation design strategies; Methodology for teamworking

1. Introduction

Research on teamworking and teambuilding seems to have given considerable attention to team skills [1,2] and work design within teams [3,4], whereas there has been less investigation into the links between teamworking and an organisation's speci"c technology, the strategic use of teamwork-ing, or the signi"cance of an organisation's culture on the form of teamworking adopted. Through our research we have come to consider teamworking as part of a strategic, corporate response to the

de-mands for increased e$ciencies and higher quality

levels, combined with #exibility and continuous

innovation, all of which are required to respond to an increasingly competitive and global market place [5]. Given this, the recent drive towards teamwork has departed from its traditional prime concern, the quality of working life [6]. Instead, the key focus now emphasise teamworking as the main organisation design parameter to improve product quality and enhance productivity and performance levels [7], in order to deliver strategic objectives and gain competitive advantage.

Attempting to purposefully design and introduce speci"c forms of teamworked social organisation to ensure the achievement of strategic priorities is a signi"cant addition to#exing the more accepted levers for competitive advantage, namely advanced technologies and integrated information systems.

`Organisational engineeringa of this kind can be

seen as an enhancement, at the level of manufactur-ing systems design, of the argument for

manufac-turing as `a strategic competitive weapona [8].

Furthermore, if teamworking is introduced as the critical social linkage connecting technologies and systems to ensure their strategic exploitation, it might be argued that it lies at the heart of a re-source-based manufacturing strategy [9].

2. Experiences with teamwork

Though many writers extol the virtues of team-working, unfortunately companies often experience di$culties in its implementation [5,10}13]. In the current climate of global competition, managers may tend to rush towards a generic team-based solution to their problems, possibly buying

consul-tants'prescriptions, or emulating the

manufactur-ing processes and organisational forms that have been adopted by companies they know, or regard, as being successful. Organisational leaders may see a particular form of teamwork adopted elsewhere

and consider this to be a panacea }something to

which they must aspire. In doing so, they may discount other options, and implement, without carefully assessing the appropriateness of the model they are considering in relation to their strategic requirements, cultural context, or the complexities of the change they are attempting. It is

namKve approaches such as these that can lead

to the notion of teamworking being discredited by both management and employees. Any organisa-tion embarking on a strategic teamworking venture needs to appreciate the long term and complex nature of the undertaking, and respond accord-ingly. The introduction of teamworking is essen-tially a strategic venture involving both organisa-tional redesign and the development of a change initiative.

Flexible, team-based approaches to manufactur-ing are implicitly linked with a general move amongst leading-edge manufacturing organisations towards a`total systems approacha, and the forma-tion of cellular organisaforma-tional structures, which aim to form natural groups of people and machinery

around information and material #ows [14]. The

change has been described by [15] as a`new theory

of manufacturinga, which will characterise the

`post-modern factory of 1999a. We have adopted

the term `New Wavea [16] as a label for this

emergent institutional form.

Because our research focus was on corporate organisational con"guration and the management of change, our work draws heavily on con"guration researchers who have conceptualised organisations holistically and drawn attention to the importance of organisational archetypes in the planning and management of change [17}19]. Particularly, Hin-ings and Greenwood's [20,21], work provides a framework for the analysis of archetypal forms. They consider the archetype in terms of the pattern formed by the interplay between interpretive schema, prescribed frameworks and emergent in-teractions.`Interpretive schemaa, embody the be-liefs, ideas and values of the designers and inform

and shape the`prescribed frameworka.`Emergent

interactionsaresult from application in response to

the interplay between the `interpretive schemaa,

the`prescribed frameworkaand external

environ-mental events. Initially developed for the study of whole organisational forms, particularly in under-standing the dynamics of change, we have adapted this model for use in our research on teams, since we consider the strategic use of teams to be the building blocks of social organisation.

3. Research methodology

Our research was undertaken from both a theor-etical and empirical perspective. Initially, we con-ducted extensive literature searches to ascertain the status of existing theory, as well as undertaking three in-depth case studies of manufacturing com-panies all of which had a considerable track record in designing and implementing teamworking. It was to these conceptual issues of the design of the teamworked organisational form on the one hand and the process of implementation on the other that the detail of our cases attended. From these data sets, we drew some tentative conclusions and developed initial conceptual models. These became the basis for our work and as our research

proceeded we integrated research "ndings, both

teamworking. By so doing, broadly we followed

a`grounded theoryaapproach [22}27].

In all, empirical work was undertaken in 14 com-panies, involving some 134 interviews with man-agers at all levels. Our research strategy "tted broadly Cohen et al.'s [28] conception of` longitu-dinal empirical studya, in which

`the research method is not direct observation,

but rather reconstruction from the organisation's written and oral histories, and perhaps from preserved artefactsa(p. 681)

Data was collected using the concept of a `time

linea, which enabled respondents to identify and

discuss both the purposes for introducing team-working and the activities which had to be under-taken including the order in which they were introduced into the company. Such an approach to data collection allowed respondents to address the issues of transformation holistically and systemi-cally, including both design and implementation

issues. The`time lineamethod proved particularly

user friendly, providing respondents with a natural method for recounting their stories, as well as pro-viding transparency of data for immediate valida-tion. Equally, this process supported further validation and triangulation of speci"c data by checking across the accounts of others in the same company. Additionally, company documentation was accessed and incorporated where available and appropriate.

4. Research5ndings;conceptual models of teamworking

The popular adoption of teamworking has been

argued to be part of companies' attempts to shift

manufacturing paradigm from the legacy`Fordista

forms [29] that dominated most Western

manufac-turing "rms for the past 50 years to the `New

Wavea forms [16] that have emerged from the

Paci"c Rim and particularly Japan. In any attempt to shift paradigm, the change is inevitably`a step

into the unknowna and therefore is likely to be

more dominated by ideas, beliefs, and recipes about

how to achieve the `new utopiaa rather than

ex-clusively driven by pragmatism and contingency. In

these circumstances it is to be expected that organ-isational con"guration is conceived and enacted in

the form of a model or archetype}it is a means of

simplifying uncertainty and focusing on key fea-tures of the desired change.

We begin with the view that teamworking was largely seen as a generic intervention. However, the "eldwork revealed much evidence of contextualis-ing di!erences in purpose, design, and implementa-tion within speci"c task environments. Although there was some evidence of the implementation of

an overall`archetypalaapproach to teamworking,

within this were di!erent types of teamworking. There were distinct di!erences in the way such approaches were structured, managed, and most signi"cantly in our view, in the underlying ideas which shaped their purpose and functioning.

Our research content analysed the case and in-terview data and identi"ed the characteristics of the overall archetypal team form, which we labelled the

`self-directeda model of teamworking. We also

identi"ed two `typesa of teamworking within the overall archetype. These appeared to be related directly to the task context of the application of teamworking, and seemed to be designed with speci"c purpose in mind. For example, in both aerospace and in the o!shore industry a strong

orientation to `projecta teams could be found,

whereas in automotive, `leana teams dominated.

These re#ected the needs of di!ering manufacturing systems (see [30]). Our view is that each of these were su$ciently separate and distinct in their ob-jectives and deliverables, as well as their form and features to be considered to be distinct types within the overall archetype. Each of these forms com-prised a speci"c prescribed format for teamworking containing features best suited for pursuing par-ticular purposes.

Brie#y, the overall self-directed archetype was characterised by the aim of introducing self-control through empowerment of sta!. Often it was

imple-mented by removing supervisory levels,#attening

the hierarchy, increasing multi-skilling, harmonis-ing conditions of employment, and introducharmonis-ing single status. The aim was to develop social control

through a committed, motivated, #exible,

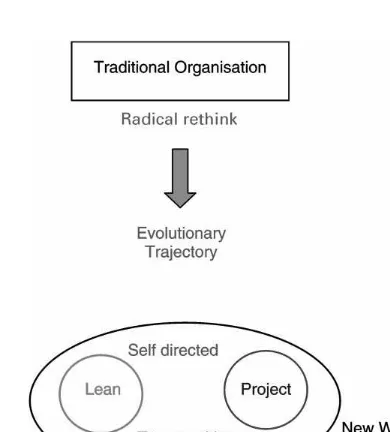

Fig. 1. Teamworking trajectory.

was the desire to break a legacy of alienation and instrumentality characteristic of many workforces. The interpretive schema underpinning the self-di-rected archetype was dominated by social system characteristics, i.e. the nature of human beings and group behavior. Its ideas, values and beliefs ad-dressed the characteristics of the technical system only inferentially, viz., meeting the need for quality and#exibility. In the literature this form of

team-working has been referred to as `self-directeda

[31}33], `Swedisha [34] and `socio-technicala

[35,36].

Within this overall archetype, the two sub-types could be found. Firstly, the lean sub-type seems best "tted to routinised task environments and aims to support, and continuously improve, demand driven production systems that are tightly-coupled and standardised, with little slack in inven-tory or time. There is formal leadership often accompanied by relatively low levels of autonomy, with most opportunities for creativity and innova-tion occurring o!-line in the search for continuous improvement. The prescribed format for lean teams is often dominated by technical system require-ments [35,36,34,29]. This can prove alienating of individuals operating in the lean teams. Indeed

much of Wickens'work has addressed ameliorating

the potentially oppressive features of lean produc-tion [37] and others have written in a similar vein [38].

Secondly, there is the project sub-type. This capi-talises on the traditional strength of the project team which has a limited life, is technically speci"c, and formed to deliver to a pre-de"ned client need usually within a prescribed time constraint and budget. The project sub-type is composed of specialists, integrated together to complete a

single, complex and multi-disciplined task.

It is appropriate in non-routine task environments such as concurrent, or simultaneous engineering and partnering, which have encouraged project teamworking across internal and external organ-isational boundaries, and the acceptance of a

de-gree of ambiguity and #uidity in design as

inevitable and necessary to achieve the objective of integrating and compressing development time scales and meeting customer requirements [1,3, 39}50].

5. Selecting an appropriate team form

Many companies are emerging toward the`New

Waveamodel from a traditional organisational

leg-acy with features such as long hierarchy and having a strong emphasis on functional division, push sys-tems, incorporating high stock levels, adversarial relations both inside and out, etc. For an organisa-tion to break from such paradigm thinking and traditional legacy, its architects and designers need help in conceptualising and articulating a clear con"guration for which to aim. The team forms previously identi"ed aid this thinking process (see Fig. 1: Teamworking trajectory). Our research suggests that the ultimate emergent form will be a combination of the overall self-directed archetype, subsequently contextualised by the task context.

Because of the idiosyncratic nature and speci"c needs of particular task environments, no generally

applicable `best-modela exists, even for the same

industry, product or technological environment [51]. Management rarely will be able to adopt either a single ideal team form, or successfully achieve all the objectives of teamworking embodied in the team types. Instead they may emphasise.

`one or two dimensions at the expense of the

The aim is for the designed team form to match the needs of the task context and provide a balance appropriate for the achievement of organisational purposes [37,38,52]. The`"taof the designed form to the existing organisation will be in#uenced by the work content, the nature of the task, the techno-logy employed, and the environment [53}60].

Our case evidence supported previous work by others, that if an organisation achieves transforma-tion to a new archetypal teamworked form, it may "nd this to be insu$cient, or possibly unstable [12]. DiMaggio and Powell [61] noted that the more an organisation is tightly coupled to a pre-vailing archetypal template within a highly struc-tured"eld, the greater its instability in the face of external shocks. In this situation, the role of incor-porating the characteristics and values of at least one other archetypal team form into its philosophy,

in essence "ne tunes the organisation to become

more integrated [21].

A`New Waveaintegrated organisational form is

an ambiguous concept di$cult to articulate with su$cient clarity to provide an achievable goal. However, the self-directed archetypal team form on the one hand, and the task based team types on the other, can be used to a!ect interpretive schema by readily providing conceptualisations of new and di!erent organisational forms which can o!er the vision for future direction. In this way the arche-type and the team arche-types can be used to assist the organisation in breaking from its existing orienta-tion or legacy, transforming the organisaorienta-tion and achieving radical change [21,62,63].

Leading-edge manufacturers are responding to a marketplace which is demanding both cheap products and high variety. This strategy requires a combination of the quality and productivity

of-fered by lean production techniques, the#exibility

and innovation that self-direction can inspire, and the ability to rapidly solve complex problems and co-ordinate the work of specialists that project teams achieve. We believe the e!ective

implementa-tion of`New-Waveaorganisational forms involves

the integration of selected team characteristics into a combination that is most appropriate to the strat-egy, culture and technology of the company. This is a complex task requiring the development of a methodology to aid managers in this process.

6. Developing the strategic designs for teamworking (SDT) methodology

This purpose of the SDT methodology, therefore, is to assist managers and organisations to navigate

the path from a traditional, or `legacy

organisa-tiona, to a `New Wavea form. Consequently, the

aim of the methodology is to encourage a more strategic approach to the adoption of teamwork-ing, such that the actions taken are in alignment with, and appropriate to, the strategic intent of the organisation. The methodology will also o!er as-sistance to those organisations that have travelled part way along the journey towards implementing an appropriate team form, but have not tackled some legacy issues, or are reverting to type because they have failed to change their infrastructure to support the new behaviours.

To undertake this development work, the project moved into an action research phase. The design of the SDT methodology assumes that strategic choi-ces about the form of teamworking best suited to speci"c manufacturing environments are con-strained by the degree to which teamwork is articu-lated in the minds and experience of the managers involved in taking the decision. If teamworking is only seen as an undi!erentiated generic approach suited to all situations, then it is di$cult to know whom to imitate, or which choice to make between various consultant o!erings, or how to design di!erent approaches to teamworking in di!erent parts of the manufacturing process. The three con-ceptual methods of teamworking upon which the SDT methodology is based are underpinned by di!erentiated assumptions and aims. The logic of the SDT methodology is to use these models to introduce the generic, self-directed form of team-working, and then subsequently to articulate the relationship between manufacturing purpose and organisational design so as to enable practitioners to identify and contextualise their speci"c experien-ces and aspirations for teamworking. The SDT methodology is intended to enable managers to better understand their current teamworking ar-rangements, evaluate how well these"t their stra-tegic purposes, and envisage and plan how these

might be improved by providing a`mapaof

1Over 300 manufacturing managers have been involved in the validation of the models resulting from this research.

However, `the map is not the territorya, and

therefore the methodology should be regarded more as a heuristic devise than an algorithm for optimising organisational design. It is aimed at encouraging managers to re#ect on what they are trying to achieve through their teamworked organ-isational designs and how di!erent con"gurations suit some manufacturing purposes better than others. Out of this process managers are able to see the strengths and limitations of their existing approaches and be more discriminating in evaluat-ing the various approaches available in the market, and can plan changes that need to be put in place to better align the con"guration of teamworking in their factory with the strategic purposes and needs of the various parts of the manufacturing process. Methodologies for introducing such changes all incorporate in some format the questions:

f Where are now?

f Where do we want to get to?

f How do we get there?

In designing such a methodology a key issue is to decide where the main motivation and energy for change resides. Does it emanate from dissatisfaction with the current situation, or does it result from the attraction of future possibilities? Most methodolo-gies seek to capitalise on both sources of motivation. Audit tools are used to generate dissatisfaction by benchmarking existing performance and practices against either best practice or some idealised model. Awareness of gaps or shortfalls becomes the ener-giser for change in de"ning what needs to be done. The alternative strategy of developing and articula-ting a vision of the future relies on the attractiveness of the envisaged future both to energise its

enact-ment and to enable the current state to be `given

upa. It is important in designing a methodology to decide what comes"rst. If most of the motivation to change is likely to come from dissatisfaction with the present then audit should precede vision; on the other hand, if the attractiveness of an alternative future is likely to be the motivator then vice versa.

Most manufacturing managers1who have been

exposed to the`mapaof teamworking

incorporat-ing the`self-directeda,`leanaand`projectamodels report experiencing it as`paradigm shiftain their thinking about teamworking. Once having heard about it, their thinking and understanding of their prior experience of teamworking is`transformeda. They talk about the three archetypes map as` revel-atoryainsofar as it illuminates areas of their team-working practice, in particular how di!erent parts of the manufacturing process with di!erent impera-tives require di!erent approaches. Typically, this has generated high levels of energy and motivation with groups of managers wanting to proceed immediately to redesign the teamworking arrange-ments. In terms of the change model described above, the teamworking map appears to have con-siderable potential for generating visions of future teamworking con"gurations. On this basis the

methodology has been designed to be `vision

drivenarather than`audit leda. Whilst we believe both are required, in this case we are clear that the vision will provide the main motivation to change with the audit revealing the potential brakes on achieving it.

Deciding the methodology should be `vision

drivenaresulted in most emphasis being placed on

designing processes to enable participants to ex-plore and elaborate the meaning and potential of the approaches to teamworking identi"ed in SDT. To do this the methodology was designed in four steps:

1. Pre-diagnosis and audit.

2. Workshop 1: Awareness raising and conceptual design.

3. Consolidation and data gathering.

4. Workshop 2: Detailed design and action plann-ing.

6.1. Stage one}orientation and audit

The aims and bene"ts of conducting an audit of the existing organisation are to surface and make explicit the taken-for-granted assumptions to the facilitating consultants, and later, in the two

work-shops to`2generate managerial debate about the

data collection include elements of artefact, values/beliefs and taken-for-granted assumptions.

The aim of the audit is to ascertain the history and current status of teamworking in the company, to identify its position on the path between tradi-tional and New Wave organisatradi-tional forms, and to discover which combination of the archetypes would be most appropriate. The audit is based on data from interviews which explore critical inci-dents in the company's history and the values and beliefs of its members with regard to teamworking; observation of organisational artefacts, structures and processes; and questionnaires involving point allocation and choice between archetypes. The audit is undertaken by external facilitators and provides background information for Workshop One, which is the key driver for change.

6.2. Stage two}Workshop One}conceptual design of teamworked organisation

The"rst stage of this workshop is educational in that it familiarises participants with the archetypal teamworking map. Speci"cally, this involves a pre-sentation of the archetype and team types, linking each to di!erent types of outcomes, and tight coup-ling the purposes for adopting teamworking to various team forms and the infrastructures required to support them.

The journey to the `New Wavea team-based

organisation is often one of radical change from one paradigm to another. It involves a fundamental shift in the cognitive structure [65] and behav-ioural patterns of managers and employees. Man-agers may be stuck in paradigm thinking and require input to help them see the options open to them. Radical change can only be made when alter-native templates are articulated, which allow them to shift the perspective through which they view the event [27,66,67]. Through the use of theoretical

models, combined with `reala and `ideal-typea

case-study illustrations, managers are provided with a framework for understanding their organisa-tion and oporganisa-tions upon which they can make informed choices.

The move to teamworking is a journey within a strategic context. It is that context which provides not only the reason for implementing teamworking

but also needs to dictate the speci"c form it will take. Where teamworking is not tightly coupled to the business strategy, implementation will falter, for it will be di$cult to get high-level endorsement and support for the whole system changes that will be necessary to make a coherent teamworked design function e!ectively. Further, the resources for implementation may be limited. Therefore, for spe-ci"cation and implementation to be successful, it is necessary to ensure that strategic intentions have been established by the organisation, and are understood in su$cient detail to be able to inform the teamworking debate. This tight coupling of proposed organisational con"guration to strategy is developed as a dominating theme in Workshop One in producing an agreed conceptual design.

In the latter part of Workshop One, the partici-pants use the three SDT models to produce an idealised view of the teamworking requirement. This involves analysing the manufacturing organ-isation into its appropriate teams and identifying which forms of teamworking are best suited to speci"c situations.

6.3. Stage three}consolidation

The participants are provided with a summary of the output from Workshop One together with a written document (an edupac), which provides them with more information on the archetypes. They are asked to re#ect on the output produced in Workshop One, and to consider what will need to change in order to bring about an ideal team-based design.

6.4. Stage four}Workshop Two

required form of teamworking and support struc-tures. This phase prioritises change in terms of feasibility and expected bene"ts.

The aim of the SDT methodology is to achieve a coherent organisational whole to deliver the established strategic purpose, by aligning an appro-priate organisational form for its achievement [68,69].

7. Conclusions

Although popular, teamworking often is proving problematic in implementation. Our work in a variety of experienced companies suggests this is because many organisations are failing to contex-tualise the archetypal self-directed model to suit their speci"c task environment, and hence to link teamworking speci"cally to their wider strategic agenda. The teamworking models developed as part of this research provide a variety of forms designed to be used within the SDT methodology to impact on the interpretive schema of managers, thus enabling them to envision and purposefully prescribe formats, designs and the paths they choose to follow. The development of the SDT methodology to facilitate this process surfaces taken-for-granted assumptions and encourages more open debate. It also facilitates a speci"cation of the necessary, detailed changes required within the social system to support the required changes.

References

[1] J.M. Kouzes, B.Z. Posner, The Leadership Challenge: How to Get Extraordinary Things Done in Organisations, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 1987.

[2] K. Fisher, Leading Self-Directed Work Teams: A Guide to Developing New Team Leadership Skills, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1993.

[3] J.R. Hackman, G.R. Oldham, Work Redesign, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1980.

[4] P.A. Goodman, Designing E!ective Work Groups, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 1986.

[5] M. Higgs, D. Rowland, All pigs are equal? Management Education and Development 23 (4) (1992) 349}362. [6] D. Buchanan, Cellular manufacture and the role of teams,

In: J. Storey (Ed.), New Wave Manufacturing Strategies, Paul Chapman, London, 1994.

[7] N. Oliver, R. Delbridge, J. Lowe, Lean production practices and manufacturing performance: International comparisons in the auto components industry, Refereed Paper, BAM Conference, 1995.

[8] W. Skinner, Manufacturing: The Formidable Competitive Weapon, Wiley, New York, 1985.

[9] V. Mole, D. Gri$ths, M. Boisot, Theory and practice: An exploration of the concept of core competence in BPX and Courtaulds, British Academy of Management Conference, Aston, September 1996.

[10] R. Kilmann, A holistic program and critical success factors of corporate transformation, European Management Journal 13 (2) (1995) 175}186.

[11] R. Howard, Brave New Workplace, Elizabeth Siftington, New York, 1985.

[12] B. Sandkull, Lean Production: The Myth which Changes the World? Lean Production. Part Two: Comparative Cultural Recipes for Management, 1994.

[13] R.F. Conti, M. Warner, Taylorism, teams and technology in re-engineering work organisations, New Technology, Work and Employment 9 (1994) 2.

[14] J. Parnaby, A systems approach to the implementation of JIT methodologies in Lucas industries, International Jour-nal of Production Research 26 (3) (1988) 483}492. [15] P.F. Drucker, The emerging theory of manufacturing,

Harvard Business Review 68 (1990) 3.

[16] A. Harrison, J. Storey, New wave manufacturing strat-egies: Operational, organisational and human dimensions, International Journal of Operations and Production Man-agement 16 (2) (1996) 63}76.

[17] R. Drazin, A.H. Van de Ven, Alternative forms of"t in contingency theory, Administrative Science Quarterly 30 (1985) 514}539.

[18] H. Mintzberg, Structure in Fives: Designing E!ective Or-ganisations, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cli!s, NJ, 1983. [19] D. Miller, P.H. Friesen, Organisations: A Quantum View,

Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cli!s, NJ, 1984.

[20] C.R. Hinings, R. Greenwood, The Dynamics of Strategic Change, Blackwell, Oxford, 1988.

[21] C.R. Hinings, R. Greenwood, Understanding radical or-ganisational change: Bringing together the old and the new institutionalism, Academy of Management Review 21 (4) (1996) 1022}1054.

[22] B.G. Glaser, A.L. Strauss, Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, Aldine, Chicago, 1967.

[23] K.E. Kram, Phases of the mentor relationship, Academy of Management Journal 26 (1983) 608}625.

[24] K.E. Kram, L.A. Isabella, Mentoring alternatives: The role of peer relationships in career development, Academy of Management Journal 28 (1985) 110}132.

[25] R.I. Sutton, The process of organisational death: Disband-ing and reconnectDisband-ing, Administrative Science Quarterly 32 (1987) 542}569.

[27] L.A. Isabella, Evolving interpretations as a change unfolds: How managers construe key organisational events, Acad-emy of Management Journal 33 (1) (1990) 7}41. [28] M.D. Cohen, R. Burkhart, G. Dosi, M. Egidi, L. Marengo,

M. Warglien, S. Winter, Routines and other recurring action patterns in organisations: Contemporary research issues, In-dustrial and Corporate Change 5 (3) (1996) 653}698. [29] C. Forza, Work organisation in lean production and

tradi-tional plants: What are the di!erences? Internatradi-tional Jour-nal of Operations and Production Management 16 (2) (1996) 42}62.

[30] D.R. Tran"eld, J.S. Smith, S. Wilson, I. Parry, M.E. Foster, Teamworked organisational engineering: Getting the most out of teamworking, Management Decision 36 (6) (1997). [31] S. Caudron, Are self-directed teams right for your

com-pany? Personnel Journal, December (1993) 76}84. [32] T.P. Mullen, Integrating self-directed teams into the

man-agement development curriculum, Journal of Manage-ment DevelopManage-ment 11 (5) (1992) 43}54.

[33] P. van Amelsvoort, J. Benders, Team time: A model for developing self-directed work teams, International Journal of Operations and Production Management 16 (2) (1996) 159}170.

[34] R. Van der Meer, M. Gudin, The role of group working in assembly organisation, International Journal of Opera-tions and Production Management 16 (2) (1996) 119}140. [35] J. Cutcher-Gershenfeld, M. Nitta, B. Barrett, N. Belhedi, J. Bullard, C. Coutchie, T. Inaba, I. Ishino, S. Lee, W.J. Lin, W. Mothersell, S. Rabine, S. Ramanand, M. Strolle, A. Wheaton, Japanese team-based work systems in North America: Explaining the diversity, California Management Review 37 (1) (1994) 42}64.

[36] W. Niepce, E. Molleman, A case study: Characteristics of work organisation in lean production and socio-technical systems, International Journal of Operations and Produc-tion Management 16 (2) (1996) 77}90.

[37] P. Wickens, The Road to Nissan: Flexibility, Quality, Teamwork, Macmillan, London, 1987.

[38] J.R. Barker, Tightening the iron cage: Concertive control in self-managing teams, Administrative Science Quarterly 38 (1993) 408}437.

[39] A. Ward, J.K. Liker, J.J. Cristiano, D.K. Sobek II, The second Toyota paradox: How delaying decisions can make better cars faster, Sloan Management Review (1995) 43}61. [40] D. Buchanan, Boddy, Management objectives in technical change, In: D. Knights, H. Wilmott (Eds.), Managing the Labour Process, Gower, Aldershot, 1986.

[41] K.B. Clark, T. Fujimoto, Product Development Perfor-mance}Strategy, Organisation and Management in the World Auto Industry, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, 1991.

[42] F. Harrison, Advanced Project Management, Gower, Aldershot, 1985.

[43] M. Jenner, C. Mabey, What is it that Makes Teams Work? A Study of 49 Project Teams in the Construction Industry. British Academy or Management Conference Proceedings, Aston Business School, Birmingham, 1996.

[44] D.S. Kezsbom, Integrated planning process } making a team work: Techniques for building successful cross-functional teams, Industrial Engineering 33 (1995) 39}41. [45] B. Metcalfe, Project management system design: A social and organisational analysis, Proceedings of The Second International Conference on Managing Integrated Manu-facturing: Strategic Organisation and Social Change, Leicester University, 1996.

[46] P.W.G. Morris, The Management of Projects, Thomas Telford, London, 1994.

[47] P.K. Smart, An empirical investigation of the factors contributing to the successful implementation of CE, in: The Proceedings of The Second International Confer-ence on Managing Integrated Manufacturing: Strategic Organisation and Social Change, Leicester University, 1996.

[48] H. Takeuchi, I. Nonaka, The new product development game}stop running the relay race and take up rugby, Harvard Business Review 64 (1) (1987) 137}146. [49] G.M. Winch, Thirty years of project management what

have we learned? British Academy or Management Con-ference Proceedings, Aston Business School, Birmingham, 1996.

[50] G.M. Winch, Contracting systems in the European con-struction industry, in: R. Whitley, P.H. Kristensen (Eds.), The Changing European Firm: Limits to Convergence, Routledge, London, 1996.

[51] F. Mueller, Teams between hierarchy and commitment: Change strategies and the internal environment, Journal of Management Studies 33 (3) (1994) 383}403.

[52] F. Carr, Introducing team working: A motor industry case study, Industrial Relations Journal 25 (3) (1994) 199}209. [53] C.C. Manz, K. Mossholder, F. Luthans, An integrated perspective of self-control in organisations, Administra-tion and Society 19 (1987) 3}24.

[54] J.W. Slocum, H.P. Sims Jr., A typology for integrating technology, organisation and job design, Human Rela-tions 33 (1980) 193}212.

[55] C.C. Manz, Self-leading work teams: Moving beyond self-management myths, Human Relations 11 (1992b) 1119}1140. [56] C.C. Manz, H.P. Sims Jr., Self-management as a substitute for leadership: A social learning theory perspective, Acad-emy of Management Review 5 (1980) 361}367.

[57] A.H. Van de Ven, A reviews framework for organi-sational assessment, in: E. Lawler, D. Nadler, C. Cam-mann (Eds.), Organisational Assessment: Perspectives on the Measurement of Organisational Behaviour and the Quality of Working Life, Wiley Interscience, New York, 1979.

[58] A.H. Van de Ven, A. Delbecq, A task contingent model of work-unit structure, Administrative Science Quarterly 19 (1974) 183-197

[59] A.H. Van de Ven, A. Debecq, R. Koenig, Determinants of co-ordination modes within organisations, American So-ciological Review 41 (1976) 322}328.

[61] P.J. DiMaggio, W.W. Powell, Introduction, in: W.W. Powell, P.J. DiMaggio (Eds.), The New Institutionalism in Organisational Analysis, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1991, pp. 1}38.

[62] G. Johnson, Strategic Change and the Management Pro-cess, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1987.

[63] D. Miller, Evolution and revolution: A quantum view of structural change in organisations, Journal of Manage-ment Studies 19 (1982) 131}151.

[64] G. Johnson, Managing strategic change: strategy, culture, action, Long Range Planning 25 (1) (1992) 28}36.

[65] K.D. Benne, The processes of re-education: an assessment of Kurt Lewin's views. In: W.G. Bennis, K.D. Benne, R. Chin, K.E. Corey (Eds.), The Planning of Change, 3rd

edition, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1976, pp. 315}326.

[66] M.W. McCall, Making sense with nonsense: helping frames of reference clash, in: North-Holland/TIMS Studies in Management Science, North-Holland, New York, 1977, pp. 111}123.

[67] W.H. Starbuck, Organisations and their environments, in: M.D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of Industrial and Organ-isational Psychology, Rand McNally, Chicago, 1976, pp. 1069}1123.

[68] R. Hamermesh, Note on Implementing Strategy, Harvard Business School, Boston, MA, 1982, Case no: 383}015. [69] H.E.R. Uyterhoeven, R.W. Ackerman, J.W. Rosenblum,