Professor Donna Lee Bowen

Abstract

Although links between economic stability and patterns of human movement have been established, very little has been written regarding a possible relationship between political stability and human mobility (Moses, 2011). An especially pressing concern, especially in the wake of the 2011 Arab Spring and increasing U.S. disengagement from Iraq, is the issue of conflict-driven internal displacement of individuals within conflict states. Historically, the issue of internal displacement has been analyzed either as analogous to the concerns of refugees, or as a purely humanitarian issue. However, increasing scholarship has shown that internal displacement, an issue which becomes more pressing with every passing year, has a direct impact upon the overall stability of post-conflict states. Using Iraq as a case study, this paper will attempt to explain the ways in which internal displacement must be analyzed not only as a humanitarian issue, but also as a factor having a direct impact upon political stability and governance,

III. Framing the Issue

The topic of internal displacement is a unique and pressing issue, one which combines the issues of refugee politics, interstate sovereignty and state conflict in new and complex ways. The United Nations first defined internally displaced persons (IDPs) as those “who have been forced to flee their homes suddenly or unexpectedly in large numbers, as a result of armed conflict, internal strife, systematic violations of human rights or natural or man-made disasters, and who are within the territory of their own country” (Cohen, 16). This definition, contentious at the time and the subject of much internal debate, was later updated to include a broader definition of coercion. IDPs were then defined as those “who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular, as a result of, or in order to avoid the effects of, armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural

Sadako Ogata, “[challenges] state sovereignty as the founding principle of international relations” (x).

Some 26 million people worldwide currently live in situations of internal displacement as a result of conflict or human rights violations (O’Brien, 4). Although internally displaced people now outnumber refugees by two to one, their plight receives far less international attention. Why is this the case? Many IDPs are extremely

vulnerable: they remain mired in conflict zones, exposed to violence on a daily basis, and often have limited access to employment, food, education and healthcare. IDPs often become both the chattel and the debris of a war zone; they are caught in the crossfire of internal conflict, and are sometimes pitted against other groups for political purposes. So what impact does displacement have upon the world’s most conflict-ridden nations? And when a conflict ends, how do displaced citizens affect their state’s rebuilding and

reconstruction?

From Global Overview 2011: People Internally Displaced by Conflict and Violence, 16. IV. Internal Conflict and Displacement Politics

Scholars and actors within the framework of displacement and refugee theory have emerged, perhaps in the past 20 years alone, as a new voice in conflict resolution and mitigation, as well as within humanitarian and aid agencies (Cohen, 13). With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the ostensible collapse of a two-poled balance of conflict, Cohen points out that an interesting conundrum arose: although fewer proxy wars were started and fought because of Cold War politics, conflict became more internally-focused even as the economies, societies and interconnected nature of states became more intensely globalized. With the rise of bodies like the European Union and increasing

persecution, conflict and violence, including 28.8 million internally displaced persons. The 2012 level was the highest recorded since 1994. Furthermore, more than half of all refugees worldwide were from five countries: Afghanistan, Somalia, Iraq, Syria, and Sudan (UNHRC 2012). Displacement, in other words, is an unspoken consequence of state conflict, one which promises to explain much about the nature of rebuilding in unstable, post-conflict states (26). So what effect, if any, does internal displacement have on a conflict state’s ability to successfully govern and secure political stability?

V. Post-Conflict Multipliers and IDPs

In this paper, I will attempt to examine the long-term effects of internal displacement upon a post-conflict society, using the example of Iraq as a case study. I argue that internal displacement is one of several consequences of violent conflict that tends to 1) be understudied, ignored and allowed to fester, and 2) has a multiplying effect on the instability of a post-conflict state. Other examples of post-conflict multipliers might include gender-based violence, high levels of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), high levels of treatable diseases and damaged infrastructure. The longer these post-conflict multipliers go unaddressed and unacknowledged by post-conflict states, the worse their impact on that state’s ability to govern and function cohesively and

effectively. I argue that Iraq’s current IDP crisis is an example of these post-conflict multipliers, and negatively impacts the state’s political stability.

VI. Literature Review

and security crisis. Cohen and Deng also discuss the conflicts which currently limit the ability of regions, states or institutions to address the unique needs of IDPs, and how these limitations affects wartime politics and reconstruction, as well as the politics of peaceful states. As they discuss, the various definitions surrounding the concept of displaced people, as well as refugees, have long been fraught with contention and confusion; as they note, the UNHCR, the U.S. Council on Refugees, and almost all NGOs have differences in their definitions of refugees and IDPs, from slight technical variations to huge and formative categorical differences. This, the authors contend, makes addressing the problem of IDP resettlement much more difficult at a regional, state and international level, because of the lack of normative procedures and understanding surrounding internal displacement (61). They analyze different global regions and their varying approaches to internal displacement, concluding that factors predisposing a state to high levels of displacement include a history of authoritarian rule, underdevelopment, mistreatment of ethnic groups, and external factors of cold war tension or geopolitical conflict (71).

to unstable governance. An increasing body of scholars joins Van Gennip in calling for a more nuanced and holistic approach to post-conflict reconstruction, one which considers the effect of “invisible” damage done to countries during periods of armed conflict. Internal displacement, with its underreporting, fuzzy legal definitions and lack of data, certainly qualifies as this type of damage (59). So what in the case of Iraq makes internal displacement function as a post-conflict multiplier, threatening the political stability of the state?

VII. Political Stability in Iraq: Accountability, Insurgency, Ethnic Conflict and Regional Politics

Several main factors threaten political stability and governance in post-2003 Iraq. Analyzing these threats, and examining the degree to which they are a result of the American invasion and ongoing civil war, makes it possible to untangle the specific indicators of government stability that we can use to analyze displacement’s influence on the Iraqi state. In general, lack of government accountability, ongoing insurgencies and ethnic politics are the key features of Iraq’s political instability that will be most helpful in this analysis. In this section, I will attempt to outline the main links between Iraqi political instability and the Six Key Dimensions of Governance outlined by the World Bank, and how I will use these indicators to analyze the connection between

displacement and political instability.

International Organization for Migration shows the ways in which this corruption and lack of accountability are related to key citizenship struggles for displaced persons. Disruption of traditional family structure, lack of physical security, removal from income and education sources, language and ethnic barriers, a lack of access to legal justice and other factors all prove debilitating barriers to participation in government on the part of displaced persons. When local authorities have an incentive to use limited resources for their own personal gain, or to neglect their legal and governance responsibilities to their citizens, this exacerbates the difficulties of displaced persons. This, in turn, turns the presence of displaced, disenfranchised citizens into a post-conflict multiplier, decreasing citizen incentives to participate effectively in government or demand accountability from their leaders.

Insurgency also proves a key factor in Iraq’s political instability, since constant physical threats prevent leaders from carrying out key changes that are unpopular with insurgent groups, and discourage the function of key aspects of governance, such as elections. An increasing body of authors continues to examine the ways in Iraq’s security situation and insurgencies affect governance and political stability (O’Brien, 34). A study conducted by Ashraf al-Khalidi and Victor Tanner even defines a link between sectarian violence and internal displacement, which they see as both a consequence and a

Office, as well as the Islamic Party and Association of Muslim Scholars (on the Sunni side) gradually became the primary providers of both security and humanitarian services, and how increasing ethnic concentration aggravated this localization of services. The authors conclude that ethnically-focused campaigns by radical armed groups and sectarian parties have gradually altered the demographic make-up of Iraqi society. This, they explain, is the goal of many insurgent and armed groups: to increase the Iraqi people’s reliance upon them, as well as to make their territory more mobilized and homogenous (5). Other scholars, such as O’Brien (2011) have examined the link between insurgency and political stability, and how this impacts displacement.

insurgent groups (505). They, along with other scholars, contribute to a growing body of work that conceives of insurgent movements as developing from and through a variety of socioeconomic stressors, ones that often have links to the ethnic politics of a state, as well as its economic and social indicators. Figure 4 below shows a graphical representation of the way in which levels of insurgent activity have moved almost consistently with periods of political instability in Iraq, such as the time surrounding the 2006 Al-Askari mosque bombing, and the controversial 2005 elections. Insurgency, in this way, becomes both an indicator and a consequence of political instability in Iraq; it also simultaneously acts as a linking mechanism in the creation and perpetuation of high levels of internal

displacement.

invasion: “Thus, societal trauma, extreme violence as a common currency in both politics and crime, and high levels of private gun ownership (both legal and illicit), combined to make the rise of collective violence in Iraq after 2003 relatively easy to organize” (33).

Tanner refers to this as a kind of geographic and sectarian-based instability, which occurs when, for instance, the Sadr Office might benefit when poor, urban Shia are displaced from Baghdad, and end up in areas like Najaf or Kerbala, contributing to the fight there against SCIRI. In fact, Khalidi and Tanner identify main four categories of Iraqis who were displaced by sectarian violence: Sunnis from Shia areas, Shia from Sunni areas, Arabs from Kurdish areas, and minority groups from Sunni and Shia areas (26). Thus, given these calculations, creating an atmosphere that encourages and perpetuates instability is to the tactical advantage of insurgent and extremist groups attempting to use citizens as pawns in their regional wars (15). Khalidi and other scholars have examined how this intense geographic instability has lead to changes in the levels of urbanized populations in Iraq, many of which are fleeing to city centers to become part of insurgent movements. Other patterns of urbanization reflect regional migration of various ethnic groups as a result of conflict or intimidation.

From “Varieties of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Iraq, 2003-2009,” 49.

Finally, external factors also tend to contribute to the perpetuation of instability in Iraqi governance, including the functions of international governance groups and aid organizations that Van Gennip outlines in his critique of post-conflict development. Cohen notes the overreliance in the MENA region on international aid organizations, particularly in Iraq, and shows how such IGOs and NGOs that deal specifically with refugees and internally displaced persons have a special degree of lack of coordination compared with other regions (61). Many issues of varying definitions, regional power and sovereignty mean that the issue of government accountability in Iraq is exacerbated from the outside; such organizations have provided the bulk of security and infrastructure funding, especially since 2003.

Dimensions of Governance identified and codified by the World Bank Development Research Group, which nicely line up with the indicators described here that are specific to the Iraqi state’s instability. The indicators are provided in the figure below. The Dimensions of Governance indicators seek to capture the degree to which states succeed in matching their economic development with political development, and attempt to do this in a non-normative fashion. As shown, the indicators measure different aspects of governance related to citizen participation, accountability of leaders, stability and absence of violence, regulatory efficacy, rule of law and corruption. All of these factors effectively describe the aspects of Iraq’s instability that I will attempt to analyze here in relation to displacement.

From “The World Bank Development Project,” www.info.worldbank.org/governance, World Bank.

VIII. Internal Displacement in Iraq: A Post-Conflict Multiplier

The issue of internal displacement in Iraq has regional, national and local

with refugees and IDPS within Iraq, security concerns and varying definitions of displacement have lead to spotty organization, a lack of common protocol and no regional focus. Indeed, as Cohen notes, the displacement crises of Sudan, Somalia and Iraq went all but unaddressed by the region’s only intergovernmental organization, the League of Arab States, who invoked the need for national sovereignty to avoid

involvement. In addition, other institutional problems plague the issue of displacement in Iraq, such as a lack of regional monitoring organizations and a general tendency for aid organizations (who would normally be the first response in dealing with displaced persons) to focus on humanitarian needs alone, and to leave any idea of security or protection out of the equation (Cohen, 236). Ineffective coordination, a lack of reach and unpredictable responses of existing organizations further exacerbate this problem (185). Other factors, including the scale of socioeconomic losses in education, employment and social services, as well as losses of property and livelihood, contribute to the inability of aid organizations or the Iraqi state to adequately address the needs and unique position of IDPs. State institutions will be able to do the best job of coming closest to addressing the needs of IDPs in a given community, but for the time being, it looks doubtful that the Iraqi state will mobilize its resources enough to address the needs of its internally displaced persons.

This, as O’Brien outlines in his 2011 study, is precisely the link between internal displacement and political stability: that a lack of resources and state cohesion prompts cycles of violence attempting to get back those resources and security, but they

community based on the actions of a few individuals, an action which disrupts

community structures until the integrity of the community as a whole is at risk (18). With pressures from the outside, and an inability of aid organizations to address the unique and hidden concerns of internally displaced persons, displacement will continue to be an exacerbating factor in the development of political stability in Iraq.

While the issues surrounding displacement can be best conceived of in terms of their most immediate relationship to conflict, natural disaster or physical insecurity, the feedback effects of violence push this phenomenon into the long-term sphere.

Displacement then becomes a post-conflict multiplier, perpetuating and multiplying the effects of this instability with ongoing time and lack of resources and attention. Tanner and al-Khalidi have written extensively about the nature of internal violence in Iraq, and how it prompts patterns of movement that force certain ethnic groups out of their homes and into differently-oriented geographical areas. As they write of the insurgent groups:

There are many parallels between the radical armed groups on both sides. Both seek to sow violence in areas where inter-communal relations remain good. Al-Washash, for instance, is a poor, mixed area near the upscale Baghdad

neighborhood of Mansur, where relations between Sunni and Shi‘a have remained good and radical sides from neither side hold sway. But in recent months many young people, both Shi‘a and Sunni, have been killed by armed men. Several local residents told of a KIA van that was caught when residents set road blocks and check points. The people in the van confessed that they had been paid to kill young people from both sides. Of course this story remains unconfirmed, but what is important is that people believe it to be true (Brookings Institute, 20).

of regional dynamics, concepts of the issue of displacement, and a pervasive kind of ethnic violence that leads to increased pressure for homogeneity in populations.

According to the Refugee Studies Center, Iraq has suffered from waves of displacement since its inception as a state, most notably during the 1970s and 1990s, when millions were externally and internally displaced in attempting to flee the harsh realities of life under Saddam Hussein (Protracted Displacement, 1). Displaced Iraqis now constitute the second largest worldwide refugee population, at approximately 2 million living abroad—for most of whom, the idea of returning home is all but

impossible. Although the study of refugee populations abroad is necessarily a different topic, complete with complex issues of its own, the inability of Iraqis to return to their own homes —whether they are one town or one continent away—is the ongoing and pervasive issue that deserves analysis. Why are huge amounts of Iraqis forced from their homes? And what happens when they cannot return home?

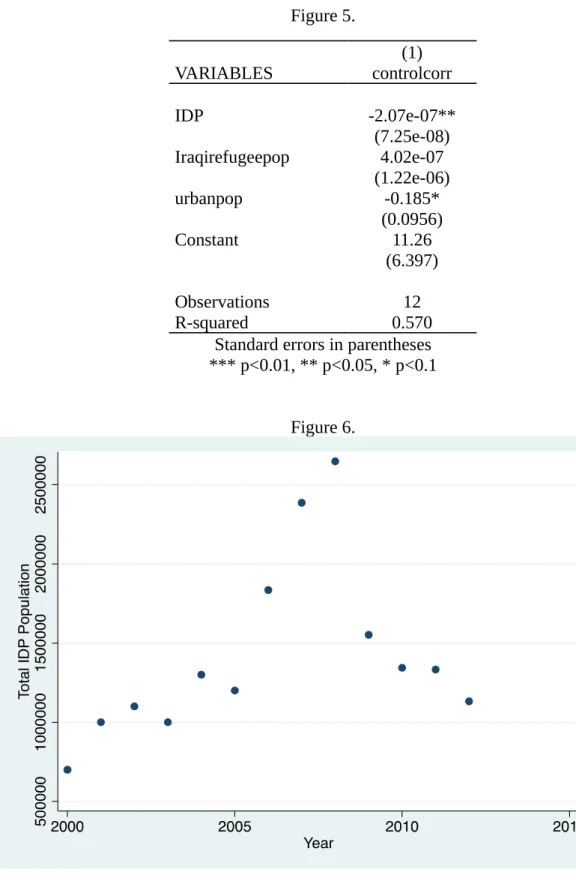

Joseph Sassoon identifies three main “waves” of forced displacement in post-2003 Iraq: the first taking place from May post-2003 to February 2006, during the initial waves of violence following the invasion; the second from February 2006 to summer 2007, following the sectarian bombing of the Al-Askari mosque; and the third during the American troop surge (10). As he notes, and as is apparent from the data, the ebb and flow of forced displacement is a function of the political situation of a given area, and the interaction between the internally-facing insurgent violence and the externally-facing IDPs, who see escape as their only option. Various socioeconomic factors contribute to this, and are important to consider separately.

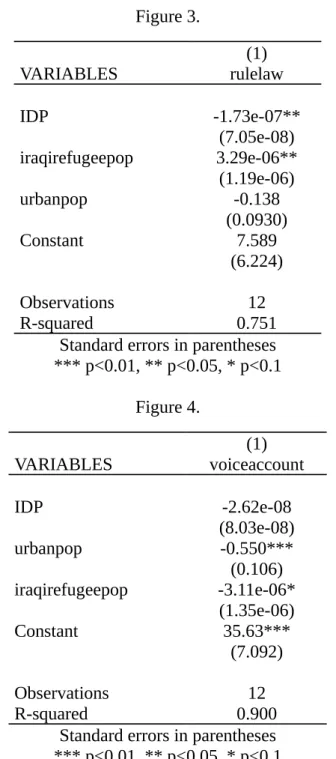

In order to properly establish links between Iraq’s displacement and political instability, I performed a series of regressions on key indicators from the years spanning from 2000 to 2013. Using the World Bank Governance Indicators, which range from -2.5 (low) to 2.5 (high) and data relating to the number of IDPs, the number of internal refugees, and the urbanization of the Iraqi population, I sought to operationalize the relationship between political stability and development.

The results of these regressions, shown in an attached appendix, are revealing. I created a variable that averaged each year’s score along each of the six indicators, and used this average score as a yearly estimate of overall political stability for each year. As shown in Figure 7, this overall score dropped intensely between 2005 and 2007, went up slightly around 2008, and began to drop off again around 2012. However, this variable showed no statistical correlation with any of the displacement indicators. For this reason, each of the six dimensions of governance was analyzed in isolation with the displacement variables, and this allowed for some important statistical relations to be established. As shown in Figure 1, there is a marked and significant relationship between overall government effectiveness and the degree of urbanization of the Iraqi population. This suggests, as previously noted, that urbanization, a symptom of displacement, can be negatively tracked with government effectiveness. The overall Iraqi refugee population and urbanized population are both statistically correlated with government effectiveness and regulatory quality at the 95% confidence level. The increase of the Iraqi IDP

population and refugee population is also negatively correlated with rule of law, and with voice and accountability. This suggests that as more refugees and IDPs enter and

participate in the Iraqi state, political stability is degraded.

There are significant limitations to the data and analysis in this study. A lack of information plagues the development workers and study of Iraq, since the security situation makes accurate data collection difficult. Similarly, the data presented here covers only 12 years, and may not be extensive enough of a set of data to draw long-term conclusions. Finally, key indicators which would be helpful to include in this analysis— including levels of government expenditure on health care and unemployment and numbers of female-headed households and children out of school—are lacking. Further research that yields data on these indicators is sorely needed.

In addition, there are many important reasons to consider alternate explanations, both for the development of Iraq’s political instability as well as its displacement

situation. Of course, alternate explanations play a role in this consideration: they are both the result of complex and interworking social, economic and political factors. As noted, one interesting contributor to the discussion of internal displacement is a difficulty in measurement and information-gathering, noted by most scholars in the field, which makes analysis of the issues of displacement extremely difficult, if not impossible. As Tanner, Cohen, and others note, the figures released by various aid organizations are often skewed one way or another based on that individual organization’s conception of refugees and IDPs, and many often combine the multiplying effects of refugees and IDPS in one single indicator. Additionally, many agencies don’t feel the need to make a

Similarly, IDPs living with family or friends often are not recorded or noticed as living in a displaced situation, and this discounts a good deal of the Iraqi IDP population.

Finally, O’Brien’s work suggests another alternate hypothesis: is the involvement of foreign troops a factor which uniquely sets apart a conflict and IDP situation like Iraq, making it an unfair comparison? The presence of an occupying force certainly multiplies the likelihood of violent or resentful responses in the form of insurgencies, and can exacerbate political instability (55). This suggests that a cross-state analysis is crucial. In order to understand the unique factors of state-level conflict and instability that

characterize displacement issues, an analysis of multiple states would be a crucial direction for future research.

XI. Conclusion

As Tanner notes in his report on sectarian-induced displacement, the violence in Iraq “is neither spontaneous nor popular” (3). He argues that most citizens would

desperately like to see a change in the rhetoric of their nation’s politics and security, one which would allow for greater vocalization of silenced topics, including displacement, homelessness and refugee status. As the US commitment in Iraq becomes less and less concrete, and less interesting to voters, it seems inevitable that the direction of Western aid and involvement in Iraq will be in NGOs and official aid organizations, and not so much in troops on the ground. So what of ongoing political instability, and its impact on the lives of everyday Iraqis?

As I have attempted to show, internal displacement has emerged as one of the most wide-reaching, pervasive and insidious effects of the conflict in Iraq, one that threatens the lives and livelihood of citizens from all sectors of life in the country.

political instability the longer it goes unaddressed. Past conceptions of displacement have counted the topic as mainly impacting humanitarian factors, but it is more complex than this. There are, as other scholars have also shown, direct links between political

instability (including insurgency, lack of accountability, and corruption), and displacement in Iraq. Like other post-conflict multipliers, displacement promises to continue as a silent but deadly drain on the Iraqi state and its ability to heal. The longer this problem goes unaddressed, the less hope there is for future generations of Iraqi citizens, at home and elsewhere.

Works Cited

Al-Khalidi, Ashraf and Victor Tanner. “Sectarian Violence: Radical Groups Drive Internal Displacement in Iraq.” The Brookings Institution: University of Bern Project on Internal Displacement. October 2006.

Al-Khalidi, Ashraf, and Victor Tanner, Sectarian Violence: Radical Groups Drive Internal Displacement in Iraq, The Brookings Institution, October 2006.

Al-Makhamreh, Sahar; Spaneas, Stefanos; Neocleous, Gregory. “The Need for Political Competence Social Work Practice: Lessons Learned from a Collaborative Project on Iraqi Refugees—the Case of Jordan.” The British Journal of Social Work42.6 (Sep 2012): 1074-1092.

Berman, Eli, Callen, Michael, and Joseph F. Felter. “Do Working Men Rebel? Insurgency and Unemployment in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Philippines.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 55 (2011): 496-528.

Output: The Role of Reforms.” International Monetary Fund: Working Paper. 2013. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1391.pdf (accessed 10 February 2014).

Couldrey, Marion and Tim Morris, eds. Iraq’s Displacement Crisis: The Search for Solutions. Special Issue. 2007. Forced Migration Review. Oxford University. http://www.fmreview.org/en/FMRpdfs/Iraq/full.pdf (accessed 16 January 2014).

Cohen, Roberta. “The Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement: An Innovation in Internal Standard Setting.” Global Governance 10, no. 4 (October 2004): 549-480. Military and Government Collection, EBSCOhost (accessed March 14, 2014).

Cohen, Roberta and Dawn Calabia, “Improving the US Response to Internal Displacement: Recommendations to the Obama Administration and the Congress,” Brookings-Bern Project on Internal Displacement, Jun. 2010. Cohen, Roberta and Francis M. Deng. Masses In Flight: The Global Crisis of Internal

Displacement. The Brookings Institution: Washington, D.C., 1998.

Chatelard, Géraldine, Incentives to Transit: Policy Responses to Influxes of Iraqi Forced Migrants in Jordan, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, Working Paper, RSC no. 2002/50.

“Country Data Reports: Iraq.” Worldwide Governance Indicators. World Bank Development Project.

http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#countryReports (accessed 11 April 2014).

“Displacement: The New 21th Century Challenge.” UNHCR: Global Trends 2012. http://unhcr.org/globaltrendsjune2013/, accessed 12 March 2014.

Dodge, Toby. “Chapter 4: Rebuilding the Civil and Military Capacity of the Iraqi

State.” Iraq: From War to a New Authoritarianism.The International Institute for Strategic Studies. 2012. 115-145.

Fawcett, John and Victor Tanner. “The Internally Displaced People of Iraq.” The Brookings Institution: University of Bern Project on Internal Displacement. October 2002.

Ferris, Elizabeth. The Looming Crisis: Displacement and Security in Iraq, The Brookings Institution, Aug. 2008.

Hughes, Geraint. “The Insurgences in Iraq, 2003-2009: Origins: Developments and Prospects. Defence Studies 10, no. 1/2 (March 2010): 152-176. Accessed March 16, 2014.

“Iraqi Protracted Displacement.” Workshop Report. Refugee Studies Center, University of Oxford. March 2012. http://www.internal displacement.org/

publications/2012/workshop-report-iraqi-protracted-displacement (accessed March 18, 2014).

Joes, Anthony James. Resisting Rebellion: The History and Politics of Counterinsurgency. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004.

Jones, Seth G. and Patrick B. Johnston. “The Future of Insurgency.” Studies In Conflict and Terrorism, 36:1 (2013): 1-25.

Lindsay, Jon and Roger Peterson. “Varieties of Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Iraq, 2003-2009.” Center on Irregular Warfare and Armed Groups. US Naval War College.

http://Lindsay-and-Petersen---Varieties-of-Insurgency-and-Counterinsurgency-in-Iraq.pdf (accessed March 18, 2014).

Moses, Jonathon. “Emigration and Political Development: Exploring the National and International Nexus.” Migration and Development 1 (2012): 123-137.

O’Brien, Brad Michael. “The US Response to the Displacement of Iraqis Since 2003. MA Diss, University of Utah, 2011.

Oliker, Olga, Audra K. Grant, Dalia Dassa Kaye, The Impact of U.S. Military Drawdown in Iraq on Displaced and Other Vulnerable Populations, Occasional Paper, Rand: National Defense Institute, 2010.

Sassoon, Joseph, The Iraqi Refugees: The New Crisis in the Middle East, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2009.

United States Government Interagency Counterinsurgency Initiative. “Counter-Insurgency Guide.” U.S. Government. January 2009.

http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/119629.pdf (accessed March 16, 2014).

UNHCR, “Internally-Displaced People,” 2001-2011, http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49c3646c146.html.

(accessed 11 April 2014).

US Department of State, Bureau of Population, Migration and Refugees, Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2005 Report to the Congress, Jan. 1, 2005, www.state.gov.

Van der Auweraert, Peter. “Was establishing new institutions in Iraq to deal with

displacement a good idea?” Forced Migration Review. Oxford University. 2013. http://www.fmreview.org/fragilestates/vanderauweraert (accessed 16 January 2014).

Van Gennip, J. (2005). Post-conflict reconstruction and development. Development, 48(3), 57-62.

doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.development.1100158

Codebook

IDP: number of internally displaced Iraqis living within Iraqi borders

iraqirefugeepop: total number of refugees of non-Iraqi origin living within Iraqi borders urbanpop: percentage of Iraqi citizens living in urbanized areas, percentage of total rulelaw: Rule of Law

voiceaccount: Voice and Accountability

poltotal: Averaged Six Indicators for Indicated Year regqual: Regulatory Quality

Figure 5.

(1)

VARIABLES controlcorr

IDP -2.07e-07**

(7.25e-08)

Iraqirefugeepop 4.02e-07

(1.22e-06)

urbanpop -0.185*

(0.0956)

Constant 11.26

(6.397)

Observations 12

R-squared 0.570

Standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1