E-commerce in China

Changing business as we know it

George T. Haley*

Department of Marketing and International Business, School of Business, University of New Haven, 300 Orange Avenue, West Haven, CT 06516, USA

Received 15 August 2000; received in revised form 1 December 2000; accepted 28 February 2001

Abstract

In discussing the future of e-commerce, many experts have assumed that e-commerce in emerging markets will evolve along the same lines as it has in the US, North America, and to a great extent, in Western Europe. This assumption fails to take into account the differences that exist between the economic infrastructures of emerging markets and those of the developed markets of the West. This article considers how China’s economic infrastructure, which like the infrastructures of most emerging markets is much less highly developed than the industrial West’s, will influence the development of e-commerce in China. By implication, the route of e-commerce development in China may be a more likely route of development for other emerging markets to follow.D2001 Elsevier Science Inc. All

rights reserved.

Keywords:E-commerce; China; Emerging markets

1. Introduction

The Internet and other new-economy technologies have proven to be tremendous sources of economic growth for the more advanced industrialized economies of North America, Europe, and Asia. But e-commerce in the West has developed as it has, and as rapidly as it has, because an existing distribution, financial, and communications infra-structure conducive to e-commerce already existed. This infrastructure has been an extremely influential technolo-gical externality that has benefited the e-commerce industry beyond measure. Yet, one assumption made by many aca-demics and practitioners when they discuss e-commerce in emerging markets is that the technological infrastructure that exists in the West’s more developed economies either exists, or will exist everywhere, and will be the technology that dominates in all markets. In emerging markets such as China there are considerable difficulties in implementing the stand-ard US model that many people in the West assume will dominate when they discuss e-commerce or make prognos-tications about it. However, local markets may determine

that, given local conditions, alternative models may be preferable, especially when dealing with the more rational and economically driven business-to-business markets.

In more-developed economies, advanced communication and computer technologies are pervasive, distribution and warehousing networks are generally extensive, fast, and reliable, and though exceptions such as Japan exist, fin-ancial/credit networks are readily available and efficient. These technologies, and the skilled work forces necessary to employ them, provide the infrastructure needed to make the new-economy technologies so powerful. Additionally, this infrastructure has largely preceded in existence the Internet technologies that have made such powerful use of them. Unfortunately, these infrastructural elements do not exist in most emerging economies (see Ref. [22]). Telephone lines have a low penetration rate in the market and computer access even lower penetration rates.

The developed economies’ preexisting infrastructures permitted the Internet and its related Web-based technolo-gies to create the fantastic cost reductions, increases in productivity, and potential for more of the same that it has in advanced economies. The established infrastructure also permits the private sector to take the fullest possible advantage of the new-economy technologies. In emerging economies, can the same benefits be generated? From our

0019-8501/02/$ – see front matterD2001 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 0 1 9 - 8 5 0 1 ( 0 1 ) 0 0 1 8 3 - 3

perspective, how can the private sector develop the kind of actual and expected returns in emerging economies from Internet-based business strategies that it has in developed economies?

This paper presents evidence that companies can gain measurable competitive advantages over their competitors in emerging markets by building their Web-based capabil-ities. However, the companies cannot simply mimic policies and strategies employed in advanced economies, they must adapt their strategies to local conditions. Section 2 explores local conditions in developing markets that elicit new strategies from companies. Section 3 sketches some strat-egies from successful companies in the developing markets. Conclusions and policy recommendations are offered in Section 4.

2. Local conditions requiring adaptation

In China, local variations in business conditions span both public sector and private sector environments.

2.1. Public sector conditions

China’s economy faces two substantial problems. First, it does not have sufficient Internet-capable communications’ infrastructure and skilled personnel to implement the same Internet strategies as the more advanced economies have done [2,4,14,16]. Second, it does not have the supporting, service-industry infrastructure to maximize the benefits of Internet tools [2,4,6,14,16]. For example, China’s Internet-based vendors can only accept credit card payments when the credit card is issued by a bank located in the same city as the Internet vendor [14]. Additionally, China’s business culture does not adapt well to the impersonal characteristics of the Internet [7].

Developing countries have faced recently the imbalance in development caused by the fascination investors have had for Internet-based investments and start-ups. China’s dot-coms, the darlings of the foreign investors, also created difficulties for the Chinese government’s privatization efforts by making it impossible for the government to attract private funds for the acquisition of government-owned companies in other, more-traditional economic sectors. Finally, China’s Communist Party is struggling to avoid any loss of power and/or influence over the nation’s economic, political, and social environments while still acquiring the benefits of the Internet and its related tech-nologies for China’s economy [7,14,15]. ChinaOnline [7] noted that five significant threats exist to a successful Web in China:

Commercial — the government owns many of the players and could interfere with private parties’ access. Corruption — this increases operating expenses for all

business, Internet-based or brick-and-mortar.

Security concerns — especially dealing with encryp-tion, where government regulators at one time insisted all encryption codes’ projected uses and copies be handed over to government regulators.

Ideology — will content providers have freedom to

operate?

Enforcement — the lack of an adequate tradition of

rule-of-law.

This list makes it plainly obvious that the government is a major element, if not the only element, in each of the five threats to the Internet’s success in China.

2.2. Private sector conditions

Though successful companies have difficulties changing their operating procedures, many overcome these difficulties to attain new success in their Internet environments. Though these companies’ strategic changes include field sales-force reductions, development of new channels of distribution and industry-wide e-trading organizations, they have usually depended on many existing infrastructural systems, such as their established delivery and financial infrastructure for their success. In China and other emerging markets, how-ever, the infrastructure that made their success possible in advanced economies often does not exist, and companies have to develop entirely new ways of doing things all over again [14].

China also presents companies with tremendous uncer-tainty regarding the government’s regulatory posture with respect to e-commerce [15], the local business culture’s resistance to adopting Internet-friendly practices [4], and intellectual property rights [11], and a scarcity of qualified personnel. Additionally, companies will face many of the same problems in China that they face elsewhere, such as the increased competition made possible by the Internet [18] and the huge amount of information and disinformation that spreads like wildfire over the Web [23].

3. Strategic solutions

Many reports on companies’ investments in China speak about the need to accept difficult times and early losses in order to invest in China. The difficulty with this piece of accepted dogma is that losses do not generate strong support at headquarters or among important corporate stakeholders. To be successful, investments must be pur-sued with intense commitment, and intense managerial commitment is developed through generating profits [24]. Thus, a key strategic element for foreign direct investment into China’s rapidly evolving economy is to generate short-term profits in order to build the critical mass of benefits that will generate management commitment to their Chi-nese investments [24]. To generate short-term profits, companies must employ all their best technologies, such as Internet-based marketing and research technologies, but they must also remember the basic tenets of appropriate technology. The best technology for an emerging market is not always the same as the best technology in a developed economy [10]. Indeed, older technology may often prove more appropriate for emerging economies than the latest, cutting-edge technologies. Managements should consider these possibilities when developing their strategic responses to the Chinese business environment’s specific conditions, which include a dearth of skilled personnel, insufficient service-industry infrastructure, WAPs, and the five threats to success.

3.1. Scarcity of skilled personnel

Managers in the Chinese business environment often confront a lack of Internet-savvy or trained personnel and have to develop them through certification programs. People can receive certification of e-commerce capability either through training or through examination [8]. Additionally, Schmit [20] reported of raiding practices undertaken to recruit Internet-capable employees; and Haley and Low [13] discussed Singapore’s effort to acquire immigrants in strategically important technologies. This scarcity of trained personnel will continue to affect China’s Internet-based commercial activities for years, and likely decades, to come.

3.2. Insufficient service industry infrastructure

Insufficient service-industry infrastructure includes poor transportation and credit facilities, and possible solutions.

3.2.1. Transportation

Until recently, the operations of courier services such as Federal Express ended once they got their packages across the Chinese border. Federal Express can now provide service within China, but its penetration of the Chinese market remains limited. No other courier service has yet obtained permission to transport packages within China.

Internet vendors usually depend on the Chinese postal service to distribute their products. Though reliable by emerging markets’ standards, China’s postal service is slow and costly, and represents one of the major complaints that customers have about e-commerce in China.

Though consumer e-marketers have to live with this slow and expensive distribution system, ingenious business-to-business marketers have overcome it. For example, one caterer that services commercial sites takes orders over the Internet and contracts with taxis to deliver his food, hot and fresh, to his customers [14]. Similarly, a bottled water com-pany operating in several major cities uses the Internet to receive orders from its clients at its headquarters where it maintains centralized order-processing and inventory records. The company then e-mails orders to regional warehouses in the various markets it serves: bicycle and human carters subsequently deliver bottled water. In both the above exam-ples, a little ingenuity and technological compromise enabled companies to maximize efficiency provided by Internet-based communications, inventory control, and order processing.

3.2.2. Credit facilities

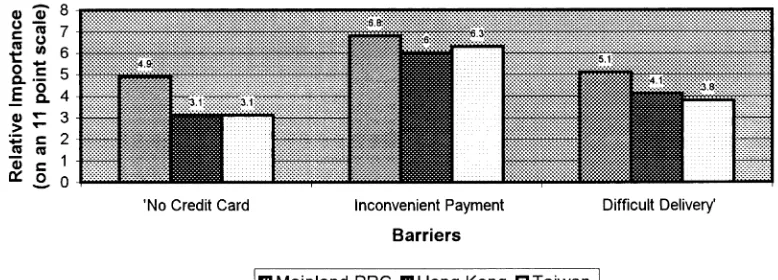

Payment constitutes the greatest e-commerce problem in China. Internet growth is doubling every 6 months [19] but credit cards are only useable in the city where the issuing bank is located. For Internet vendors to accept credit card payments they must have offices located in the same cities as the banks that issued the credit cards; no nationally accepted credit cards exist in China. Consequently, Internet vendors cannot take advantage of many of the benefits of the Internet, especially in B-to-C businesses. The results of a survey taken by the Cheskin Research and Chinadotcom are presented in Fig. 1; not having a credit card and difficulties with payment were two of the most important reasons for not purchasing online. One adaptation for this condition, as mentioned earlier, includes Internet portals and Internet vendors main-taining offices in all of China’s major cities to process orders through their offices in each market. When this solution becomes financially practical, vendors can build market share today rather than waiting until conditions are ideal.

face-to-face negotiation: the services have been the site’s key to success.

3.3. The Wireless Application Protocol (WAP)

The WAP may offset China’s poor infrastructure and limited penetration of PC-based Internet services. Though very few private PC connections exist, cellular phones have become ubiquitous in China and no longer appear as conspicuous consumption [4]. Chinese cellular phone subscriptions are presently growing by 1,000,000 new subscribers a month; their growth is projected to be 37%, compounded annually, through 2006 [21]. Chinese consumers have not responded well to the WAP due to its limitations [5]; but in China, where infrastructure hinders economic growth and development, the WAP’s usefulness to businesses should overcome its limitations until its technology matches its potential. Most PCs owned by businesses in China have multiple users. In a survey, 70% of Chinese cellular phone users considered their phones primarily or exclusively business tools [5]. Consequently, the WAP’s unpopularity among consumers should have limited affect on the development of wireless e-commerce in business-to-business markets. B2B e-commerce is forecast to be 10 times greater than B2C e-commerce in Asia [17]. The Chinese business culture also favors the development of B2B e-commerce. Chinese businesses tend to form long-term relationships and use established channels of distribution for their products. These factors tend to diminish the importance of face-to-face meetings once the relationship is established. Additionally, because B2B exchanges tend to use established credit lines, many of the payment problems associated with B2C e-com-merce do not seem relevant.

3.4. The five threats to success

The five threats to success in China include issues dominated by the government: commercial factors, enforce-ment, corruption, ideology, and security concerns. Three of

these threats, commercial factors, corruption, and enforce-ment, are already under withering attack by a government that seems seriously divided on the desirability of the Internet, free markets, and private business.

The commercial factor, governmental participation in Chinese industry, was and is so tremendous, that though privatization proceeds, the Chinese government will have a significant presence in industry for the foreseeable future. This holds true for all business segments — manufacturing, agriculture, services, and distribution. Out-side of the postal service, the military provides the sole transportation and distribution of resources that can reach all areas within China. The military also remains the largest industrial concern in China, including within its dominion companies that produce consumer goods. Con-sequently, companies that wish to serve some of China’s more remote or less populated regions frequently find themselves competing against the military, their only option for transporting their goods.

enforcement of intellectual property rights has followed economic development. But China has not enjoyed uniform economic development: income in urban centers averages three times the income in rural areas [4]; and in some rural regions and regions dominated by the old government-owned heavy industries, average per capita income levels have fallen over the last decade. Hence, unless Beijing can reassert its authority over the provin-cial governments, significant difficulties will continue regarding enforcement of the laws in the books.

The government is also tacklingcorruption, but as with the previously discussed problems, no victory appears in sight. The potential misuses of the fight against corruption add to the difficulties in rooting it out. Many feel that political motivations and tensions between China’s economic reform-ers and its Old Guard drive some charges of corruption. However, legitimate anticorruption efforts are also underway. As the government continues its efforts to harness corruption, companies’ profitability should be enhanced.

Finally,ideologyand security concernswill continue to be problems so long as the Communist party insists on maintaining social and political control of China. Though many authors continue to differentiate between China’s reform and antireform-oriented leaders, management must remember that all Chinese leaders are first and always loyal communists. Whatever their economic perspective, Chinese governmental leaders support policies that they believe will most likely maintain the Communist Party’s power in China. The Communist leadership’s economic ideology may vary, but its ideology of power and its maintenance adheres to those espoused in this party for almost half a century.

Security concerns appear preeminently on the mind of China’s leaders and bureaucrats. For example, many mem-bers of the government seem convinced that Microsoft’s programs, and all other computer programs produced by US companies, come equipped with backdoors accessible by the US government [4] — this is what China’s government would like to do. To try and combat this danger, China’s government demanded that companies deposit copies of all encryption programs with governmental regulators who could track encrypted communications. The Chinese gov-ernments’ distrust of commerce and foreign powers has existed for centuries and has been felt most strongly by their own businesses [12]. This distrust forms an integral part of communism, and also of Confucianism, so it is likely to continue. Business interests must be prepared to fight for their interests, through any available legal, political, and social channels, whenever ideological and security issues arise. Businesses should: (1) Keep scrupulous records and data to prove the basic honesty and straightforwardness of their intentions in any and all business dealings; (2) Develop the strongest relationships possible with both central and provincial governments, and with private business interests, to argue their case if necessary; and (3) Remember that China remains a public law system of justice rather than a rights-based system. In public law systems, an individual’s

rights originate entirely from the governing authority’s willingness to recognize and to grant those rights to the individual, and not on an inherent possession of rights guaranteed by law [3,11]. The next section offers some implications and policy recommendations.

4. Conclusions

The future for e-commerce appears very bright in China, but that future can suffer catastrophically at the hands of a divided and suspicious government. Present growth rates of e-commerce-related activities can continue unabated for many years to come if the government controls the five threats. This growth potential exists whether one considers technologies with relatively low market penetration, such as the PC-based Western-style Internet; or those with relatively high market penetration, such as in cellular phones. Invest-ing in China’s communications and other e-commerce-related businesses appears as a necessity for companies that hope to achieve globally competitive positions, but it entails substantial risk. Motorola, currently (February 2001) the largest single investor in China [9,21], has demonstrated that its strategy carries substantial risk and uncertainty. China’s markets possess many problems, but managers can surmount these if they adapt to the infrastructural, business, and political situations that they will face. To enter China successfully, a company must commit to China for the long-term; but high risks and uncertainty call for high liquidity and rapid returns. Commitment includes several variables, and a willingness to stick with an invest-ment for the long-term forms only one. Another equally important element includes the strength of one’s commit-ment. As Yan [24] has pointed out, companies cannot maintain strong commitments without showing profits for the effort. As regards profit expectations, managers should approach China, despite its potential, with the reservations and cautions of any other developing market.

References

[1] Berkman B. Information losing value/impeding decision-making, posted Friday, February 21, 1997 ( http://www2.osl.state.or.us/ archives/libs-or.html ).

[2] Barnert R, Gupta R, Lee JB, Schroepfer AM, Gould GM, Tan S. B2B commerce/Internet Asia Pacific: B2B@sia Powered by e-frastructure. New York: Goldman Sachs Global Equity Research, 2000. [3] Carver A. Open and secret regulations in China and their implication

for foreign investment. In: Child J, Lu Y, editors. Management issues in China, international enterprises. London: Routledge, 1996. pp. 11 – 29. [4] Cheskin Research. Greater e-China insights. Prepared in cooperation

with China.com, Redwood Shores, US, October 2000.

[5] China.Com. Chinese mobile users give thumbs down to WAP. January 10, 2001. pp. 1 and 4.

[6] ChinaOnline News. E-commerce in China: horse drawn buggies on the information highway? December 29, 1999.

[8] ChinaOnline News. New program to train China companies in e-commerce. June 12, 2000b.

[9] ChinaOnline News. Motorola becomes largest foreign investor in China. February 6, 2001.

[10] Dunn PD. Appropriate technology. New York: Shoken Press, 1979. [11] Haley GT. Intellectual property rights and foreign direct investment in

emerging markets. Mark Intell Plann 2000;18(5):273 – 80 (Special issue on ‘‘Strategic Marketing in Emerging Economies’’).

[12] Haley GT, Tan CT, Haley UCV. New Asian emperors: the overseas Chinese, their strategies and competitive advantages. Oxford (UK): Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998 (164 pp.).

[13] Haley UCV, Low L. Crafted culture: governmental sculpting of mod-ern Singapore and effects on business environments. J Organ Change Manage 1998;11(6):530 – 53.

[14] Jeffrey L. China’s wired. Toronto: Stonecutter Communications, 2000a. [15] Jeffrey L. New Internet rules: red tape or money grab. China’s Wired.

2000;4(11). (Newsletter, November).

[16] Lee JB, Barnet R, Murray C, Yamashina H, Gupta R, Berquist TP, Friedman J. B2B commerce/Internet Asia Pacific: B2B@sia: e-volution or e-xtinction. New York: Goldman Sachs Global Equity Research, 2000.

[17] Marks SJ. Asia/Pacific market is not just big — it’s complex. Micro-times Mag, 210 (August 1, available at MicroMicro-times.com).

[18] MeetChina.Com. MeetChina.com expands to Korea with nation’s most popular trade portal. Business to business section, December 6, 2000. [19] Richardson M. Internet gap is widening for Asians: experts seeking

ways to narrow digital divide. Int Herald Trib 2000 (September 14).

[20] Schmit J. Internet revolution rolls through Asia. USA Today 2000 (February 11).

[21] Snyder C. Motorola (China) plans move into broadband, Net products. ChinaOnline News, February 5, 2001.

[22] Economist.. From bamboo to bits and bytes. Survey of Asian busi-ness. Economist 2001;22:8 (April 7 – 13).

[23] Varian HR. The information economy. Sci Am 1995;273:200 – 1 (September).

[24] Yan R. Short-term results: the litmus test for success in China. Harv Bus Rev 1998;76(5):61 – 9. (Sept. – Oct., Reprint 98511, 11 pp.).