Associations of the shared and unique aspects of positive and negative

emotional factors with sleep quality

Jesse C. Stewart

⇑, Kevin L. Rand, Misty A.W. Hawkins, Jennifer A. Stines

Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), Indianapolis, IN, USA

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 14 September 2010

Received in revised form 23 November 2010 Accepted 3 December 2010

Available online xxxx Keywords:

Sleep Quality Depression Anxiety Anger Positive Affect Rumination

a b s t r a c t

Because most studies have examined only one emotional factor at a time, it is not clear which features of these overlapping constructs are important determinants of sleep quality. Our aims were to determine which aspects of negative emotional factors are most strongly associated with poor sleep quality, whether positive emotional factors are independently related to improved sleep quality, and whether rumination explains the links between emotional factors and sleep quality. A total of 224 young men and women completed questionnaires assessing depressive symptoms, trait anxiety, trait anger, trait positive affect, trait rumination, and sleep quality. Structural equation models revealed that greater Neg-ative Affect – the shared variance among the negNeg-ative emotional factors – predicted poor Sleep Quality

(b= .62,p< .0001,DR2= .38); however, unique effects of the positive and negative emotional factors were

not detected. Rumination did not account for the observed relationship. Our findings suggest that the shared, but not unique, aspects of negative emotional factors may be key determinants of sleep quality.

Ó2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of sleep difficulties is high and on the rise. Approximately 64% of American adults (versus 51% in 2001) report having experienced one or more sleep problems at least a few nights a week (National Sleep Foundation, 2009), and about 6% meet criteria for an insomnia diagnosis (Ohayon, 2002). Notably, sleep dysfunction is a predictor of poor health outcomes. Both objective and subjective measures of sleep quality have been found to be predictive of all-cause mortality (Dew et al., 2003; Kripke, Garfinkel, Wingard, Klauber, & Marler, 2002). Other studies have demonstrated that poor sleep quality is associated with an in-creased risk of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease (Schwartz et al., 1999) and diabetes (Ayas et al., 2003). Given the widespread, deleterious effects of poor sleep on health, a crucial next step is to identify determinants of this emerging risk factor.

1.1. Negative emotional factors and sleep quality

Several potential determinants of poor sleep fall in the domain of stable, trait-like emotional factors. Individuals with depressive disorders consistently report sleep complaints and exhibit abnor-malities in sleep architecture (Tsuno, Besset, & Ritchie, 2005). Unlike depression, investigations of anxiety have found little objec-tive evidence of sleep architecture changes, although reports of insomnia are common (Papadimitriou & Linkowski, 2005). Studies examining anger suggest that it is also related to indicators of poor sleep (Caska et al., 2009; Shin et al., 2005), and similar results have been observed for the related constructs of hostility and aggression (Brissette & Cohen, 2002; Ireland & Culpin, 2006).

Most previous studies, however, have examined the effect of a single negative emotional factor on sleep quality, which consider-ably limits the inferences that can be drawn. Because depression, anxiety, and anger are overlapping constructs and cluster within individuals (Clark & Watson, 1991; Spielberger, 1988), it is not known whether each of these emotional factors is independently associated with sleep quality or whether one (or more) is merely a marker for another emotional factor. To illustrate the latter pos-sibility, anxiety could be inversely correlated with sleep quality so-lely due to its strong relationship with depression, which itself may be a determinant of poor sleep. Yet another plausible model is that the individual negative emotion-sleep quality relationships are dri-ven by a shared underlying personality trait, such as negative affectivity (Watson & Clark, 1984). To evaluate these competing

0191-8869/$ - see front matterÓ2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.004

Abbreviations:PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; BMI, body mass index; STAI, Trait Anxiety Inventory; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; STAXI, State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory; PANAS, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; ECQ-R, Rehearsal scale of the Emotional Control Questionnaire; SEM, structural equation modeling; SRMR, Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual; RMSEA, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; CFI, Comparative Fit Index.

⇑ Corresponding author. Address: Department of Psychology, IUPUI, 402 North Blackford Street, LD 100E, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA. Tel.: +1 317 274 6761; fax: +1 317 274 6756.

E-mail address:jstew@iupui.edu(J.C. Stewart).

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Personality and Individual Differences

j o u r n a l h o m e p a g e : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / p a i d

models, investigations are needed in which multiple emotional factors are simultaneously examined as correlates or predictors of sleep quality. Unfortunately, only a small number of these types of studies exist (depression and anxiety:Jansson & Linton, 2006; Johnson, Roth, & Breslau, 2006; Mallon, Broman, & Hetta, 2000; Morphy, Dunn, Lewis, Boardman, & Croft, 2007; depression and an-ger:Caska et al., 2009; Shin et al., 2005), and none has examined all three negative emotional factors.

1.2. Positive emotional factors and sleep quality

Another topic that has received limited attention is whether positive emotional factors are associated with improved sleep quality. Although past studies have detected a link between psychological well-being and improved sleep (Nes, Roysamb, Reichborn-Kjennerud, Tambs, & Harris, 2005), the multidimen-sional nature of this construct makes it difficult to discern the specific influence of its positive components. Similar associations have been detected in investigations examining more narrowly de-fined constructs, such as trait positive affect and life satisfaction (Steptoe, O’Donnell, Marmot, & Wardle, 2008; Strine, Chapman, Balluz, Moriarty, & Mokdad, 2008). However, because few studies have adjusted for negative emotions (Gray & Watson, 2002; Steptoe, O’Donnell, Marmot, & Wardle, 2008), it is not known whether positive emotional factors are independent determinants of sleep quality.

1.3. The present investigation

To address these gaps, we conducted a study of young adults in which positive and negative emotional factors, rumination, and sleep quality were assessed. We measured trait rumination because relationships between this cognitive factor and both negative emo-tions and sleep quality have been reported (Thomsen, Mehlsen, Christensen, & Zachariae, 2003; Zoccola, Dickerson, & Lam, 2009). Furthermore, rumination and related constructs are identified as key factors in current models of insomnia (Harvey, 2002). Thus, rumination is one mechanism through which emotional factors may have an impact on sleep quality. Our aims were to determine (a) which aspects of overlapping negative emotional factors (shared versus unique) are most strongly related to poor sleep quality, (b) whether positive emotional factors are independently associated with improved sleep quality, and (c) whether trait rumination explains the emotional factor-sleep quality associations.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

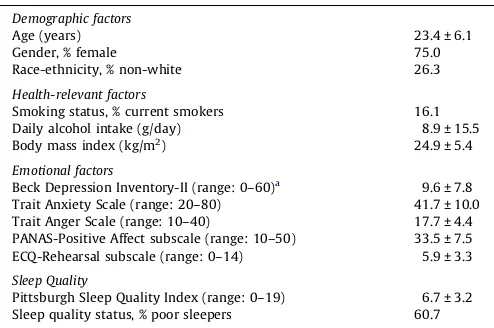

Our sample consisted of 224 young adults enrolled in courses at a large urban university. This study was approved by the institu-tional review board at Indiana University-Purdue University India-napolis. Besides the requirement of ageP18 years, there were no inclusion criteria. Of the 257 enrolled students, we excluded indi-viduals who reported current use of psychotropic medication (n= 18), did not complete all of the PSQI items (n= 10), were miss-ing data for BMI or smokmiss-ing status (n= 4), or did not complete the STAI Trait Anxiety scale (n= 1). The characteristics of the final sam-ple are shown inTable 1.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Negative emotional factors

To assess depressive symptoms, trait anxiety, and trait anger, we administered the BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), Trait

Anxiety scale of the STAI (Spielberger, 1983), and Trait Anger scale of the STAXI (Spielberger, 1988), respectively. The BDI-II is a 21-item, self-report measure of depressive symptom severity that has been shown to have high internal consistency, test–retest reli-ability, and construct validity (Beck et al., 1996). We did not in-clude Item 16 (changes in sleeping pattern) due to concerns that it might artificially inflate the correlation between the BDI-II and PSQI. The Trait Anxiety scale is a 20-item, self-report measure that provides an assessment of stable individual differences in the pro-pensity to experience anxiety. This scale has high internal consis-tency and test–retest reliability, and it correlates strongly with other trait anxiety measures (Spielberger, 1983). The Trait Anger scale is a 10-item, self-report measure that assesses stable individ-ual differences in tendency to experience anger. It has also been found to be internally consistent, reliable over time, and valid (Spielberger, 1988).

2.2.2. Positive emotional factors

We assessed trait positive affect with the 10-item Positive Affect (PA) scale of the widely used PANAS (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). Participants were asked to report the extent to which they had experienced ten positive emotions during the past few weeks. The PANAS-PA scale has been shown to be internally consistent and stable over time, and it correlates with other self-report and peer-rated measures of positive affect (Watson & Clark, 1994).

2.2.3. Trait rumination

The Rehearsal scale of the ECQ (Roger & Najarian, 1989) was administered to measure trait rumination. It is a 14-item, true– false instrument that provides an index of one’s general tendency to repeatedly think about negative events (e.g., ‘‘I find it hard to get thoughts about things that have upset me out of my mind.’’). This scale has satisfactory internal consistency and test–retest reli-ability (Roger & Najarian, 1989), and it has been found to be corre-lated with other rumination measures (Siegle, Moore, & Thase, 2004).

2.2.4. Demographic and health-relevant factors

The questionnaire battery included items assessing age, gender, race-ethnicity, and smoking status. Because few participants identified their race-ethnicity as Asian/Pacific Islander (n= 14), Hispanic/Latino (n= 11), Native American/Eskimo/Aleut (n= 1), or Table 1

Characteristics of participants (N= 224). Demographic factors

Age (years) 23.4 ± 6.1

Gender, % female 75.0

Race-ethnicity, % non-white 26.3

Health-relevant factors

Smoking status, % current smokers 16.1

Daily alcohol intake (g/day) 8.9 ± 15.5

Body mass index (kg/m2

) 24.9 ± 5.4

Emotional factors

Beck Depression Inventory-II (range: 0–60)a 9.6 ± 7.8

Trait Anxiety Scale (range: 20–80) 41.7 ± 10.0 Trait Anger Scale (range: 10–40) 17.7 ± 4.4 PANAS-Positive Affect subscale (range: 10–50) 33.5 ± 7.5 ECQ-Rehearsal subscale (range: 0–14) 5.9 ± 3.3 Sleep Quality

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (range: 0–19) 6.7 ± 3.2 Sleep quality status, % poor sleepers 60.7 Note:Values are means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and per-centages for categorical variables. PANAS = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; ECQ = Emotion Control Questionnaire.

aItem 16 omitted.

Other (n= 5), race-ethnicity was coded as white versus non-white. BMI was calculated from self-reported height and weight. Daily alcohol intake was computed using a quantify-frequency method (Garg, Wagener, & Madans, 1993) and was log transformed to re-duce positive skew.

2.2.5. Sleep quality

The PSQI (Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989) is a 19-item measure of subjective sleep quality during the past month. The seven component scores (subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction) are summed to calcu-late a global score. A global score of >5 is indicative of severe impair-ment inP2 areas or moderate impairment inP3 areas; individuals with scores >5 have been classified as ‘‘poor sleepers’’ (Buysse et al., 1989). The PSQI has adequate internal consistency and test–retest reliability and is able to distinguish between groups with varying degrees of sleep disturbance – i.e., sleep-disordered patients, depressed patients, and controls (Buysse et al., 1989).

2.3. Procedure

Participants attended a 1-h assessment session held in a com-puter laboratory, during which they completed the questionnaire battery on a secure website. To ensure privacy, individuals were separated by at least one empty terminal. Participants were awarded course credit at the end of the session.

2.4. Data analysis

We first performed correlational analyses to quantify the degree of overlap among the emotional measures and to examine the associations of the emotional factors with sleep quality. Next, we used SEM with maximum likelihood estimation using LISREL 8.8 (Joreskog & Sorbom, 2008) to test the hypothesized latent-variable models. To assess model fit, we examined absolute (model

v

2 -sta-tistic and SRMR), parsimonious (RMSEA), and incremental (CFI) fit indices (Hu & Bentler, 1999).3. Results

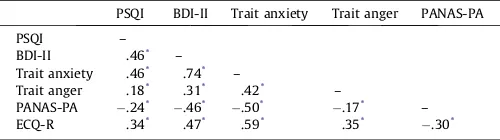

3.1. Correlational analyses

Bivariate correlations revealed that there was substantial over-lap among the emotional factors, as they shared 3–55% of the var-iance (seeTable 2). In addition, partial correlations between the emotional measures and the PSQI were all significant, and most were moderate in size. The BDI-II, Trait Anxiety, and Trait Anger scores were associated with poorer sleep quality, whereas the PANAS-PA score was related to better sleep quality.

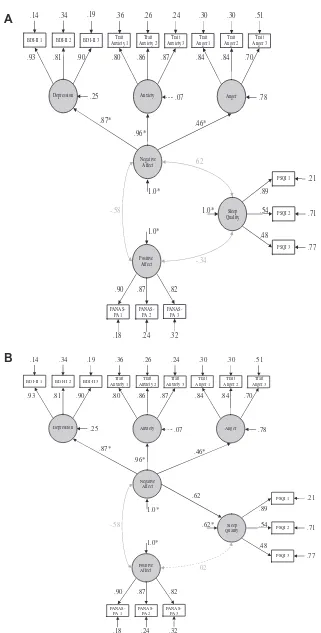

3.2. Structural equation models

We first created a measurement model consisting of the first-order latent variables of Depression, Anxiety, Anger, Positive Affect, and Sleep Quality. We aggregated items into three parcels per scale because modeling a large set of measured indicators adversely af-fects model fit (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). To rule out potential confounders, we adjusted the PSQI parceled indi-cators for age, gender, race-ethnicity, smoking, daily alcohol intake, and BMI.1We also modeled a second-order latent variable of

Nega-tive Affect as driving the first-order latent variables of Depression, Anxiety, and Anger. In the measurement model, Negative Affect, Positive Affect, and Sleep Quality were freed to correlate. This model showed acceptable fit to the data,

v

2(84,N=224)= 143.36 (p= 0.0006), RMSEA = .051, CI90: (0.034, 0.067), SRMR = 0.047, CFI = .98. As can be seen in Panel A ofFig. 1, the correlations among Negative Affect, Positive Affect, and Sleep Quality were significant (allps < .0001).

To determine which aspects of the negative emotional factors were most strongly associated with sleep quality, we first freed a structural path from Negative Affect to Sleep Quality. The signifi-cant path (b= .62,p< .0001) indicates that shared aspects of the negative emotional factors strongly predicted poorer sleep quality (seeFig. 1, Panel B), accounting for 38% of the variance. To illustrate this effect, we computed the percentage with a PSQI global score >5 for each tertile of the Negative Affect latent variable score, which revealed that 31%, 68%, and 84% of those in the lower, mid-dle, and upper tertile, respectively, were poor sleepers. We then freed the structural paths from each of the first-order latent vari-ables to Sleep Quality, one at a time, to examine whether there were unique effects of depression, anxiety, and anger. Individually freeing the paths from Depression [D

v

2(1,N=224)= 0.40 (p= 0.53)], Anxiety [D

v

2(1,N=224)= 0.02 (p= 0.89)], and Anger [D

v

2(1,N=224)= 1.13 (p= 0.29)] did not improve model fit. Furthermore, the struc-tural paths from Depression (b= .13, p= .48), Anxiety (b= .13,p= .90), and Anger (b= .09,p= .30) were all nonsignificant. Taken together, these results indicate that only the shared aspects of the negative emotional factors influence sleep quality. To evaluate whether the positive emotional factor was associated with better sleep quality, we next freed the structural path from Positive Affect to Sleep Quality. The nonsignificant path (b= .04,p= 0.69) suggests that trait positive affect may not exert an independent, protective effect on sleep quality.

Finally, we included the first-order latent variable of Rumina-tion, which was modeled using three parceled indicators from the ECQ-R. Negative Affect, Positive Affect, Rumination, and Sleep Quality were freed to correlate. This model showed acceptable fit,

v

2(126,N=224)= 198.61 (p= 0.0009), RMSEA = .044, CI90: (0.029, 0.058), SRMR = 0.047, CFI = .99. We then estimated three structural paths. The paths from Negative Affect to Sleep Quality (b= .59,

p< .0001) and Negative Affect to Rumination (b= .69, p< .0001) were significant, whereas the Rumination to Sleep Quality path was not (b= .03,p= .81). These results are inconsistent with trait rumination being a mediator of the negative affect–sleep quality relationship.

4. Discussion

Our study is the first to examine the associations of the shared and unique aspects of negative and positive emotional factors with Table 2

Correlations among measures of emotional factors, trait rumination, and sleep quality.

PSQI BDI-II Trait anxiety Trait anger PANAS-PA

PSQI –

BDI-II .46* –

Trait anxiety .46* .74* –

Trait anger .18* .31* .42* –

PANAS-PA .24* .46* .50* .17* –

ECQ-R .34* .47* .59* .35* .30*

Note: N= 224. Correlations involving PSQI are partial correlations controlling for age, gender, race-ethnicity, body mass index, cigarette smoking, and daily alcohol intake. PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II, PANAS-PA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Positive Affect subscale, and ECQ-R = Emotion Control Questionnaire-Rehearsal subscale.

*p< .05.

1 We residualized the PSQI parceled indicators instead of including the demo-graphic and health-relevant factors in the models as covariates, as the latter would have yielded a ratio of participants to estimated parameters below the acceptable lower limit of 5:1 (Kline, 2005)

BDI-II 1 BDI-II 2 BDI-II 3 Trait Anxiety 1

PANAS-PA 1

PSQI 1

Sleep Quality

Positive Affect Negative

Affect

.14 .34 .36 .19 .26 .24

.93 .81 .90 .80 .86 .87

.07

.87*

.96*

1.0*

1.0*

.90 .87 .82

.89

.54

.48

.18 .24 .32

1.0*

-.58

Depression Anxiety

.30 .30 .51

.84 .84 .70

.78

Anger

.25

.46*

.21

.71

.77

PSQI 2

PSQI 3

-.34 .62 Trait

Anxiety 2 Trait Anxiety 3

Trait Anger 1

Trait Anger 2

Trait Anger 3

PANAS-PA 2

PANAS-PA 3

BDI-II 1 BDI-II 2 BDI-II 3 Trait Anxiety 1

PANAS-PA 1

PSQI 1

Sleep Quality

Positive Affect Negative

Affect .14 .34 .19 .24.36 .26

.93 .81 .90 .80 .86 .87

.07

.87*

.96*

1.0*

1.0*

.90 .87 .82

.89

.54

.48

.18 .24 .32

.62*

-.58

Depression Anxiety

.30 .30 .51

.84 .84 .70

.78 Anger .25

.46*

.21

.71

.77 PSQI 2

PSQI 3

.02

Trait Anxiety 2

Trait Anxiety 3

Trait Anger 1

Trait Anger 2

Trait Anger 3

PANAS-PA 2

PANAS-PA 3

.62

A

B

Fig. 1.(A) Measurement model of Depression, Anxiety, Anger, Negative Affect, Positive Affect, and Sleep Quality. (B) Structural model of Negative Affect as a predictor of Sleep Quality. Values associated unidirectional arrows between variables are standardized regression coefficients, bidirectional arrows between variables are Pearson correlation coefficients, and unidirectional arrows pointing at a single variable represent error variances. Paths with significant values are solid, whereas paths with nonsignificant values are dashed. BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II. PANAS-PA = Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Positive Affect subscale. PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.N= 224. ⁄Coefficient fixed to 1.0 prior to standardization.

sleep quality. We report three important findings that address existing gaps. First, we found that the shared aspects of depression, anxiety, and anger were more strongly related to sleep quality than were the unique aspects. Structural equation models revealed that Negative Affect – a latent variable representing the shared variance among the negative emotions – was associated with poorer sleep quality, whereas depressive symptoms, trait anxiety, and trait an-ger were not in the presence of the Negative Affect variable. The observed relationship may be clinically meaningful, as 84% of adults with Negative Affect scores in the upper tertile were identi-fied as poor sleepers versus only 31% of those with scores in the lower tertile. Our results raise the possibility that a common underlying factor may account for the associations of individual negative emotional factors with sleep quality detected in past studies. Furthermore, the failure to take into account the overlap among negative emotional factors could explain previous inconsis-tent results (cf.Jansson & Linton, 2006andJohnson et al., 2006). Whether or not a particular negative emotion is found to be asso-ciated with sleep quality in a given sample may depend on the ex-tent to which the emotional measure taps this underlying common factor.

Defined as a pervasive disposition to experience negative emo-tions across situaemo-tions (Watson & Clark, 1984), negative affectivity has recently been examined as a determinant of sleep quality, and an inverse association has been detected (Danielsson, Jansson-Fröjmark, Linton, Jutengren, & Stattin, 2010; Fortunato & Harsh, 2006; Gau, 2000; Gray & Watson, 2002; Williams & Moroz, 2009). In contrast to our investigation (which employed SEM to ex-tract a measure of negative affectivity), most previous studies have used neuroticism subscales of personality inventories to assess negative affectivity and did not simultaneously examine the effects of individual emotional factors. Critically, the results of the existing neuroticism-sleep studies are ambiguous, given that any one of the negative emotional factors (i.e., depression, anxiety, or anger) could have been driving the observed relationships.

The second noteworthy finding was that the positive emotional factor did not exert an independent, protective effect on sleep qual-ity. Although the bivariate correlation between trait positive affect and sleep quality was significant, no association was observed in the SEM model. Thus, our results suggest that positive emotion mea-sures may be related to sleep quality merely because they are mark-ers of the absence of negative affect. Results of another investigation support this conclusion (Brissette & Cohen, 2002). In two other stud-ies, however, high positive emotionality was associated with im-proved sleep quality, even after controlling for negative emotions (Gray & Watson, 2002; Steptoe et al., 2008). A possible explanation for these conflicting findings is that our latent Negative Affect variable may overlap with positive affect measures to a greater extent than the global assessments used in past studies.

Our third important finding was that trait rumination did not play a role, as a mediator or a confounder, in the negative affect– sleep quality relationship. Negative Affect remained related to Sleep Quality in the presence of Rumination, even though Rumina-tion was correlated with the PSQI in the univariate analyses and was associated with Negative Affect in the SEM analyses. Our re-sults contrast with the finding that negative emotions and rumina-tion are independent correlates of sleep quality (Thomsen et al., 2003). While our findings suggest that rumination may not be part of the causal chain linking negative affect and sleep, they should not be overinterpreted. First, we may have detected mediation if we had examined other forms of perseverative cognition, such as trait worry (Brosschot, Gerin, & Thayer, 2006), or momentary cog-nitive activity, such as state rumination or worry (Brosschot, Van Dijk, & Thayer, 2007). Second, rumination may be associated with some aspects of sleep quality, such as sleep latency, but not others (Zoccola et al., 2009).

4.1. Limitations

One limitation of our study is the cross-sectional design, which precludes us from drawing directional inferences. It is possible that chronically experiencing negative emotions contributes to the onset of insomnia (Jansson & Linton, 2006; Johnson et al., 2006) or that insomnia is a risk factor for emotional disturbances (Danielsson et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2006). Another limitation is that we used a self-report measure to assess sleep quality. In a study comparing subjective and objective sleep assessments (Means, Edinger, Glenn, & Fins, 2003), individuals with insomnia tended to underestimate their sleep duration relative to controls, a finding that raises concerns regarding the accuracy of self-reports of sleep. Although evidence linking subjective sleep quality to health outcomes attests to its importance (Kripke et al., 2002), fu-ture studies should explore whether the same pattern of results is found when sleep quality is assessed by actigraphy or polysomnog-raphy. A third limitation is that we derived our measure of nega-tive affectivity from scales assessing depression, anxiety, and anger only. Future studies should obtain a broader assessment by including measures of other facets of negative affectivity, such as disgust and scorn. A final limitation is that our participants were healthy, young adults, although an advantage of such a sample is that there is a low probability that medical conditions are operat-ing as confounders. Additional investigations are needed to deter-mine whether our findings extend to middle-aged or older adults and to various patient groups, such as those with mood, anxiety, or sleep disorders.

4.2. Conclusions

In sum, we show for the first time that the shared, but not the unique, aspects of depression, anxiety, and anger may be impor-tant determinants of sleep quality. From a research perspective, our results underscore the importance of simultaneously examin-ing overlappexamin-ing emotional constructs and teasexamin-ing apart the influ-ence of their common and unique features. Had we examined the emotional factors one at a time only, we would have reached vastly different conclusions. From a clinical perspective, our findings lead us to speculate that including a module designed to reduce nega-tive affectivity may enhance the potency of psychological interven-tions for insomnia. Similarly, the efficacy of interveninterven-tions designed to prevent or treat depressive and anxiety disorders might be en-hanced by concurrently addressing sleep quality.

References

Ayas, N. T., White, D. P., Al-Delaimy, W. K., Manson, J. E., Stampfer, M. J., Speizer, F. E., et al. (2003). A prospective study of self-reported sleep duration and incident diabetes in women.Diabetes Care, 26, 380–384.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the beck depression inventory(2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. Brissette, I., & Cohen, S. (2002). The contribution of individual differences in

hostility to the associations between daily interpersonal conflict, affect, and sleep.Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 1265–1274.

Brosschot, J. F., Gerin, W., & Thayer, J. F. (2006). The perseverative cognition hypothesis: A review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation and health.Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60, 113–124.

Brosschot, J. F., Van Dijk, E., & Thayer, J. F. (2007). Daily worry is related to low heart rate variability during waking and the subsequent nocturnal sleep period. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 63, 39–47.

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research.Psychiatry Research, 28, 193–213.

Caska, C. M., Hendrickson, B. E., Wong, M. H., Ali, S., Neylan, T., & Whooley, M. A. (2009). Anger expression and sleep quality in patients with coronary heart disease: Findings from the heart and soul study.Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 280–285.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 316–336.

Danielsson, N. S., Jansson-Fröjmark, M., Linton, S. J., Jutengren, G., & Stattin, H. (2010). Neuroticism and sleep-onset: What is the long-term connection? Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 463–468.

Dew, M. A., Hoch, C. C., Buysse, D. J., Monk, T. H., Begley, A. E., Houck, P. R., et al. (2003). Healthy older adults’ sleep predicts all-cause mortality at 4 to 19 years of follow-up.Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 63–73.

Fortunato, V. J., & Harsh, J. (2006). Stress and sleep quality: The moderating role of negative affectivity.Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 825–836. Garg, R., Wagener, D. K., & Madans, J. H. (1993). Alcohol consumption and risk of

ischemic heart disease in women.Archives of Internal Medicine, 153, 1211–1216. Gau, S. F. (2000). Neuroticism and sleep-related problems in adolescence.Sleep, 23,

495–502.

Gray, E. K., & Watson, D. (2002). General and specific traits of personality and their relation to sleep and academic performance.Journal of Personality, 70, 177–206. Harvey, A. G. (2002). A cognitive model of insomnia.Behaviour Research & Therapy,

40, 869–893.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Ireland, J. L., & Culpin, V. (2006). The relationship between sleeping problems and aggression, anger, and impulsivity in a population of juvenile and young offenders.Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 649–655.

Jansson, M., & Linton, S. J. (2006). The role of anxiety and depression in the development of insomnia: Cross-sectional and prospective analyses.Psychology & Health, 21, 383–397.

Johnson, E. O., Roth, T., & Breslau, N. (2006). The association of insomnia with anxiety disorders and depression: Exploration of the direction of risk.Journal of Psychiatric Research, 40, 700–708.

Joreskog, K. G., & Sorbom, D. (2008).LISREL (version 8.8). Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International.

Kline, R. B. (2005).Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press.

Kripke, D. F., Garfinkel, L., Wingard, D. L., Klauber, M. R., & Marler, M. R. (2002). Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia.Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 131–136.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173.

Mallon, L., Broman, J. E., & Hetta, J. (2000). Sleeping difficulties in relation to depression and anxiety in elderly adults. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 54, 355–360.

Means, M. K., Edinger, J. D., Glenn, D. M., & Fins, A. I. (2003). Accuracy of sleep perceptions among insomnia suffers and normal sleepers.Sleep Medicine, 4, 285–296.

Morphy, H., Dunn, K. M., Lewis, M., Boardman, H. F., & Croft, P. R. (2007). Epidemiology of insomnia: A longitudinal study in a UK population.Sleep, 30, 274–280.

National Sleep Foundation (2009).Summary of findings of the 2009 sleep in America Poll. Washington, DC: National Sleep Foundation.

Nes, R. B., Roysamb, E., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Tambs, K., & Harris, J. R. (2005). Subjective wellbeing and sleep problems: A bivariate twin study.Twin Research & Human Genetics: The Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies, 8, 440–449.

Ohayon, M. M. (2002). Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn.Sleep Medicine Reviews, 6, 97–111.

Papadimitriou, G. N., & Linkowski, P. (2005). Sleep disturbance in anxiety disorders. International Review of Psychiatry, 17, 229–236.

Roger, D., & Najarian, B. (1989). The construction and validation of a new scale for measuring emotion control.Personality and Individual Differences, 10, 845–853. Schwartz, S., Anderson, W. M., Cole, S. R., Cornoni-Huntley, J., Hays, J. C., & Blazer, D. (1999). Insomnia and heart disease: A review of epidemiologic studies.Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 47, 313–333.

Shin, C., Kim, J., Yi, H., Lee, H., Lee, J., & Shin, K. (2005). Relationship between trait-anger and sleep disturbances in middle-aged men and women. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58, 183–189.

Siegle, G. J., Moore, P. M., & Thase, M. E. (2004). Rumination: One construct, many features in healthy individuals, depressed individuals, and individuals with lupus.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 645–668.

Spielberger, C. D. (1983).Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (form Y). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Spielberger, C. D. (1988).State-trait anger expression inventory professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Steptoe, A., O’Donnell, K., Marmot, M., & Wardle, J. (2008). Positive affect, psychological well-being, and good sleep. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 64, 409–415.

Strine, T. W., Chapman, D. P., Balluz, L. S., Moriarty, D. G., & Mokdad, A. H. (2008). The associations between life satisfaction and health-related quality of life, chronic illness, and health behaviors among US community-dwelling adults. Journal of Community Health: The Publication for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, 33, 40–50.

Thomsen, D. K., Mehlsen, M. Y., Christensen, S., & Zachariae, R. (2003). Rumination – Relationship with negative mood and sleep quality.Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 1293–1301.

Tsuno, N., Besset, A., & Ritchie, K. (2005). Sleep and depression.Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66, 1254–1268.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposition to experience aversive emotional states.Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465–490.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1994).The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. Ames: University of Iowa.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Williams, P. G., & Moroz, T. L. (2009). Personality vulnerability to stress-related sleep disruption: Pathways to adverse mental and physical health outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 598–603.

Zoccola, P. M., Dickerson, S. S., & Lam, S. (2009). Rumination predicts longer sleep onset latency after an acute psychosocial stressor.Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 771–775.