Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:47

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Alignment of University Information Technology

Resources With the Malcolm Baldrige Results

Criteria for Performance Excellence in Education: A

Balanced Scorecard Approach

Deborah F. Beard & Roberta L. Humphrey

To cite this article: Deborah F. Beard & Roberta L. Humphrey (2014) Alignment of University Information Technology Resources With the Malcolm Baldrige Results Criteria for Performance Excellence in Education: A Balanced Scorecard Approach, Journal of Education for Business, 89:7, 382-388, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.916649

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2014.916649

Published online: 29 Sep 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 118

View related articles

Alignment of University Information Technology

Resources With the Malcolm Baldrige Results

Criteria for Performance Excellence in Education:

A Balanced Scorecard Approach

Deborah F. Beard and Roberta L. Humphrey

Southeast Missouri State University, Cape Girardeau, Missouri, USA

The authors suggest using a balanced scorecard (BSC) approach to evaluate information technology (IT) resources in higher education institutions. The BSC approach illustrated is based on the performance criteria of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award in Education. This article suggests areas of potential impact of IT on BSC measures in each of the Baldrige Results Categories of the performance criteria. Many of the identified areas of measurement and expected improvement are unique to educational institutions. The multiple-faceted evaluation approach should provide improved assessment of an institution’s IT resources and offer a broadened perspective of IT usage in the academic setting.

Keywords: balanced scorecard, higher education, information technology

Businesses and educational institutions invest significant amounts of money and time in decisions involving informa-tion technology (IT). Universities are increasing usage of IT resources to attract, admit, advise, enroll, instruct, support, and assess students. To make an appropriate selection of additional IT investments, an educational institution should specify its objectives and goals and evaluate how well each potential IT resource would assist in achieving these aspira-tions. Several questions should be answered. What is the relationship of IT investments to the institution’s mission, core values, and objectives to achieve sustainable results in today’s challenging educational environment? Why is IT resource allocation, deployment, and alignment important? What potential areas of measurement and performance will IT impact? Answers to these important questions should assist educational institutions in selecting and integrating IT resources.

Traditional tools (e.g., capital budgeting techniques) do not give appropriate consideration and weight to important benefits of additional IT resources. Entities (including edu-cational organizations) have to look beyond traditional

cost/benefit analysis when evaluating IT resources. Many benefits of IT integration are difficult to measure or remain hidden in traditional, functional costing systems. For exam-ple, IT integration can improve data accuracy, customer service, decision making, and productivity. Various techni-ques are available to evaluate IT investments; discussion of several of these techniques follows in the next section.

PUBLISHED IT INVESTMENT EVALUATION METHODS

Measuring the effectiveness of IT has consistently been ranked as one of the top ten issues in major surveys of information systems managers (Ball & Harris, 1982; Bran-cheau & Wetherbe, 1987; Dickson, Leistheser, Wetherbe, & Nechis, 1984). Other authors have focused on IT and cus-tomer satisfaction and IT and productivity (Brynjolfsson & Hitt, 1995; Brynjolfsson & Yang, 1996; Sinan, Brynjolfs-son, & Van Alstyne, 2006).

Parker, Benson, and Trainor (1988) reported five basic techniques for evaluating benefits from IT investments: (a) traditional cost/benefit analyses, (b) value linking that esti-mates business process improvements, (c) value accelera-tion that evaluates increased speed of delivering information, (d) value restructuring that calculates Correspondence should be addressed to Deborah F. Beard, Southeast

Missouri State University, Donald L. Harrison College of Business, Department of Accounting, One University Plaza, MS5815, Cape Girar-deau, MO 63701, USA. E-mail: dfbeard@semo.edu

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.916649

productivity increases of employees and the organization, and (e) innovation evaluation that estimates the cutting-edge business practices derived from the IT investment. Ward (1990) presented a portfolio approach to allocating investments in IT, dividing potential IT investments into four categories: Strategic (critical to future), high poten-tial (important to future), key operational (needed for current success), and support (valuable but not critical to current success). He proposed that each category have a different required level of expected return based on the traditional cost/benefit analyses, value linking, and value acceleration measures recommended by Parker et al. Ward believed the higher the risk of failing in a category should demand a higher required level of return in the category.

Sethi and King (1994) provided a methodology for assessing IT investments’ competitive advantage. Violino (1997) reported use of embellished Return on Investment approaches to evaluate IT investment with modern portfolio theory and economic value added.

Tallon, Kraemer, and Gurbaxani (2000) developed a process-oriented model to evaluate IT investment (based on corporate executives’ perceived value of IT investment). The model considered the focus of corporate IT goals and management practices to influence critical value-chain activities. They found that corporate executives perceived a higher payoff of the IT investment (a) the more focused the IT goal and (b) the more the IT goal aligned with the busi-ness’ goals. Barclay (2008) presented a six-dimensional approach to evaluating IT that considers the stakeholder, project process, quality, innovation and learning, benefit, and use.

Several prior studies have examined the potential for the application of the balanced scorecard (BSC) approach to higher education. Some studies suggested how BSC could be implemented in an education environment (Cullen, Joyce, Hassall, & Broadbent, 2003; Hafner, 1998; Papenhausen & Einstein, 2006; Ruben, 1999; Sutherland, 2000). Other studies have detailed BSC measures to man-age and evaluate administrative and academic activities (Beard, 2009; Chen, Yang, & Shiau, 2006; Karathanos & Karathanos, 2005; Umashankar & Dutta, 2007; Umayal & Suganthi, 2010). Chang and Chow (1999) reported accounting department heads were generally supportive of BSC’s applicability and benefits to accounting programs in enhancing strategic planning and continuous improvement efforts. Bremser and White (2000) explained how BSC was used in curriculum design for an accounting program. Kim, Yue, Al-Mubaid, Hall, and Abeysekera (2012) explored the use of the BSC perspectives in assessing information sys-tems and computer information syssys-tems programs. Schobel and Scholey (2012) studied the use of the BSC to assess the distance learning environment in higher education, highlighting the importance of focusing on financial strategies.

Al-Zwyalif (2012) pointed to the importance of using BSC in developing countries and queried deans, deputy deans, heads of scientific departments, financial manag-ers and administrative managmanag-ers in Jordanian Private Universities. He determined that the leaders in these pri-vate institutions were aware of BSC and believed that the basic resources to implement BSC were available. Kamhawi (2011), using a Delphi process, determined that IT plays a critical role in the adoption of BSC. However, none of those authors focused on using a BSC approach in evaluating IT.

Before looking at a suggested application of the BSC to evaluating the IT resource, this paper presents a brief dis-cussion of strategic planning and the IT resource in the next section.

STRATEGIC PLANNING PROCESS AND IT RESOURCES

Educational institutions have increasingly undertaken stra-tegic planning to improve achievement of organizational objectives and operational efficiency. Components of the educational strategic plan (mission, vision, objectives, strat-egies, goals, and initiatives) should be of high importance and properly communicated to stakeholders-administrators, faculty, employees, students, parents, and future employers. Measuring and reporting performance consistent with the institution’s mission, objectives, goals, and initiatives requires a multifaceted approach. A BSC approach that considers various areas of measurements should be an integral part of the strategic planning and management system.

IT relates to the strategic planning process in a variety of ways. IT can be a valuable communications tool. IT may support the attainment of other objectives and goals by pro-viding efficient and effective means of collecting, process-ing, and reporting performance data. Competency of students, faculty, and staff in IT may be an explicit institu-tional aspiration. The availability and utilization of IT resources to enhance the students’ educational experience and expand access to programs could be an explicit institu-tional aim. IT may assist in developing and marketing the institution’s brand or uniqueness and in cultivating relation-ships with alumni, employers, and potential benefactors. IT can help demonstrate fiscal responsibility, stewardship of resources, and compliance with laws and regulations. IT can provide a safer campus with warning systems for vari-ous campus and community emergencies. Thus, IT repre-sents not only a desired resource, but also a tool used to improve communication, to achieve and evaluate goals, to safeguard other resources, and to provide better services to constituents. The next section will demonstrate a BSC approach in evaluating IT resources in a university setting.

ALIGNMENT OF UNIVERSITY IT RESOURCES 383

APPLYING A BSC APPROACH TO IT RESOURCES OF AN EDUCATIONAL ENTITY

To date, no single technique has been effective in dem-onstrating the wide range of benefits derived from IT. Measuring IT benefits using only financial measures is problematic because some benefits are often hard to quantify in dollars and IT intangible benefits are excluded. Difficulty arises when trying to measure quali-tative improvements with quantiquali-tative metrics. Here we explore how the criteria for the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (a BSC approach) could be used in considering IT investments in a university.

A BSC should be a component of a strategic man-agement system that links the entity’s mission, core val-ues, and vision for the future with strategies, targets, and initiatives explicitly designed to inform and moti-vate continuous improvement efforts (Hoffecker, 1994; Kaplan & Norton, 1992, 1993, 1996a, 1996b; Maisel, 1992; Newing, 1994, 1995). Aligning IT resources with the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award perfor-mance criteria reveals both financial and nonfinancial benefits of IT initiatives and demonstrates how IT is an important consideration in the strategic management system.

Kaplan and Norton (1992) first introduced the BSC con-cept in theHarvard Business Reviewarticle, “The Balanced Scorecard-Measures that Drive Performance.” The basic premise of the BSC is that financial results alone cannot measure and explain value-creating activities (Kaplan & Norton, 2001). Kaplan and Norton (1992) suggested that organizations should develop a comprehensive set of finan-cial and nonfinanfinan-cial measures of performance. They sug-gested that measures address the follow four perspectives:

1. financial perspective, 2. customer perspective,

3. internal business processes perspective, and 4. learning and growth perspective.

The measures in these four perspectives must align with the company’s vision and strategic objectives (Kaplan & Norton, 1996a). The identification of goals, measures, and targets consistent with the organization’s vision, mission, and objectives should integrate with strategic planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Building on the BSC approach, the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award performance criteria for the educa-tion award:

. . .are designed to help educational institutions use an inte-grated approach to organizational performance manage-ment that results in 1) the delivery of ever-improving value to students and stakeholders, contributing to education qual-ity and organizational stabilqual-ity, 2) improvement of overall

organizational effectiveness and capabilities, and 3) organi-zational and personal learning. (Baldrige National Quality Program, 2009, p. 51)

The 2013–2014 criteria require that applicants for this award specify results in the following outcomes areas (Bal-drige National Quality Program, 2013):

1. Student learning and process results (customer per-spective and internal business process perper-spective): Should demonstrate the effectiveness of instruction and curriculum on student learning for all student segments and the students’ satisfaction in learning outcomes. Key learning results and process effective-ness and efficiency results that directly serve students should be considered. Performance measures should include, as examples, the capacity to improve student performance, student development, and the educa-tional climate; indicators of responsiveness to student or stakeholder needs; and key indicators of accom-plishment of organizational strategy and action plans that impact on student learning.

2. Customer-focused results (customer perspective): Should involve satisfaction measurements concern-ing educational programs, service features and deliv-ery, and complaint resolutions that bear on student development and learning. Reported results should measure and analyze long-term relationships and engagement of students and stakeholders.

3. Workforce-focused results (learning and growth per-spective): should measure important characteristics of the work environment (productivity, learning-cen-tered, engagement, and care for employees). Mea-surement parameters should include, for examples, innovation and suggestion rates; retention rates; internal promotion rates; courses or educational pro-grams completed; increase in certification levels of employees; knowledge and skill sharing; employee well-being, absenteeism, and turnover; and number of employee grievances.

4. Leadership and governance results: Should evaluate the organization’s leadership, governance, strategic plan achievement, and social responsibility. Perfor-mance measures include achievement of the strategic objectives; internal and external fiscal accountability; indicators of ethical behavior, stakeholder trust in the governance of the organization, regulatory and legal compliance, safe environment, and organizational citizenship.

5. Budgetary, financial, and market results (financial perspective): Should measure the entity’s key bud-getary, financial, and market results including an assessment of the effectiveness of financial resources management, long-term financial viability, and mar-ket opportunities and risks.

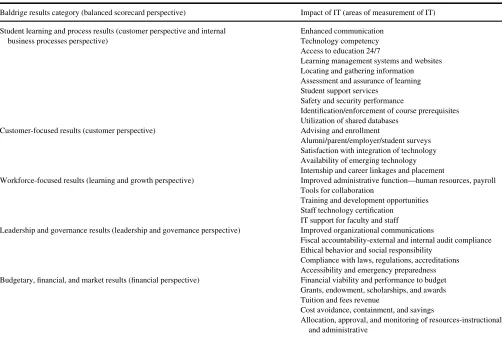

These results areas represent a balanced scorecard for an educational institution. IT has the potential for impacting the above perspectives in both direct and indirect ways. Using the Malcolm Baldrige BSC approach, Table 1 high-lights the alignment of IT resource applications in an educa-tional institution to the five outcomes or results criterion.

HOW IT CAN ENHANCE STUDENT LEARNING AND PROCESS RESULTS?

The student learning and process results criteria are unique to educational institutions. The evaluation of a business or typical government agency would not consider a student learning outcome. Integration of IT can directly and indi-rectly impact student learning results. Focusing on student competencies in technology is an important component of a university education to prepare students to thrive in today’s IT-dominated world.

Computer-based testing gives students quicker and indi-vidualized feedback from the assessments (examinations, homework). Technology (through learning management systems, email, course web pages, and course chat rooms or

forums) has allowed connectivity between the student, course instructor, and other students. Computer- and web-based programs allow students to acquire and reinforce topics through instant grading. Instructor and course web-sites support face-to-face courses by providing access to additional learning materials. In more recent years, online courses have expanded the traditional classroom around the globe and to 24/7 access.

IT enables the university to provide better service to its students by providing services online. Online registration allows quicker and more convenient course enrollment. Computerized verification of students’ records for course prerequisites allows for better assurance that only eligible students enroll in a course. Use of electronic waiting lists for full courses more fairly and efficiently distributes seats to the first on the list. IT resources allow students to get quick answers to questions with self-service query capabili-ties, such as running a report to determine the courses needed to complete their selected degree.

Quicker identification and better supervision of at-risk students is possible with the aid of IT resources. Electronic monitoring of grades and class attendance through online grade books and online attendance reporting enables more TABLE 1

Relating Information Technology to the Balanced Scorecard Perspectives of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award in Education

Baldrige results category (balanced scorecard perspective) Impact of IT (areas of measurement of IT)

Student learning and process results (customer perspective and internal business processes perspective)

Enhanced communication Technology competency Access to education 24/7

Learning management systems and websites Locating and gathering information Assessment and assurance of learning Student support services

Safety and security performance

Identification/enforcement of course prerequisites Utilization of shared databases

Customer-focused results (customer perspective) Advising and enrollment

Alumni/parent/employer/student surveys Satisfaction with integration of technology Availability of emerging technology Internship and career linkages and placement

Workforce-focused results (learning and growth perspective) Improved administrative function—human resources, payroll Tools for collaboration

Training and development opportunities Staff technology certification

IT support for faculty and staff

Leadership and governance results (leadership and governance perspective) Improved organizational communications

Fiscal accountability-external and internal audit compliance Ethical behavior and social responsibility

Compliance with laws, regulations, accreditations Accessibility and emergency preparedness Budgetary, financial, and market results (financial perspective) Financial viability and performance to budget

Grants, endowment, scholarships, and awards Tuition and fees revenue

Cost avoidance, containment, and savings

Allocation, approval, and monitoring of resources-instructional and administrative

ALIGNMENT OF UNIVERSITY IT RESOURCES 385

immediate detection of students having trouble. Exception reporting of these students could alert proper personnel so immediate intervention can be considered.

IT can improve communication within an educational institution. Electronic communications (e.g., email, instant messaging, texting) improves the efficiency of communica-tion by allowing individuals to generate a message when a question arises, then work on other matters while waiting for a reply. The recipient can retrieve messages when it is convenient, not requiring the meeting of the two or more individuals for telephone conversations or face-to-face meet-ings. A person or department can disseminate information to many interested parties through a mass communication or posting of information on a password-protected webpage.

HOW IT CAN ENHANCE CUSTOMER-FOCUSED RESULTS?

Analysis of IT impact on customer-focused outcomes is different in an educational institution from the evalua-tion of a business or typical government agency because of the various customers’ diverse needs. Obviously, the customers of an educational institution and its IT resour-ces include the students. Other customers include future employers of the students, alumni, students’ parents, faculty, staff, and community.

Course scheduling using IT can provide many benefits. Possible benefits include elimination of scheduling conflicts in terms of time, place, and personnel. Monitoring of course demand allows modification of course offering based on actual demand. Use of current enrollment data could assist in forecasting future courses needed.

Not only can advisors and advisees stay connected by electronic communications and websites, IT resour-ces also allow quick acresour-cess to online transcripts and degree requirement reports. Instant generation of what-if analyses assist during advising sessions what-if students are considering different majors/minors.

HOW IT CAN ENHANCE WORKFORCE-FOCUSED RESULTS?

The first two areas of results (student learning and process results, customer-focused results) in the performance crite-ria for the education award evaluate functionality unique to educational institutions. Educational institutions will use IT in unique ways to achieve the student learning and cus-tomer-focus outcomes. In the remaining results areas, edu-cational institutions may use IT in manners similar to businesses and governmental organizations.

IT resources provide tools for collaboration at increased communication speeds. This empowers faculty members to share and receive ideas on improved teaching effectiveness,

undertake research and professional development, and net-work with colleagues and other professionals.

Technology allows increased professional development opportunities for staff and faculty. IT resources allow train-ing of faculty and staff by ustrain-ing online courses, webcasts, and interactive television that can involve quicker delivery of new information that traditional methods of training and professional development (written instruction manuals and face-to-face sessions). The human resource function has also been transformed by IT. Many employee forms or data entry screens are available online to allow employees to self-service changes in tax and benefits information. Having payroll information digitally sent to financial institutions and check stubs available online has significantly reduced paper and distribution costs.

IT can also provide improved efficiency and communi-cation in facilities management repairs and maintenance. Personnel can complete an online work order request and receive electronic notifications when a work request is accepted, scheduled, and completed, or why the work request was denied.

RELATED TO LEADERSHIP AND GOVERNANCE RESULTS

Effective and efficient use of IT resources can improve stra-tegic management of the institution. Improved two-way communication and participation with constituents can result from IT usage and should improve the development and distribution of the university’s mission, strategic vision, core values, and priorities. Faculty, staff, administrators and other stakeholders should play an active role in the develop-ment of the mission and vision statedevelop-ments and in the priori-ties of the university. IT can provide efficient ways to solicit input and feedback.

IT resources can enhance communications of matters other than just strategic planning. Electronic communica-tion is often faster, easier, and cheaper than tradicommunica-tional mail, memo distribution, or people assembly. Selective dis-tribution of electronic communication can reduce informa-tion overload from frivolous data. IT resources can improve the internal control system. Transactions should require proper authorization (controlled by user identification and password of individuals creating or approving the transac-tion). Electronic controls can prevent improperly autho-rized transactions. Programming of the system could highlight particularly large transactions, actions undertaken by someone other than the employee with assigned respon-sibility, actions taken from an address other than the typical or a local address, or cases where management electroni-cally overrode the programmed controls. Controls need to be in place to assure that the educational entity complies with laws, regulations, and students’ privacy rights. IT resources can monitor, perform, and enforce these controls.

IT resources can also enable an institution to provide individualized services to students with special needs (dis-ability services). IT resources can be used to convert printed materials to larger print or audio for students with visual impairment. Computerized testing could replace pencil-and-paper examinations for students with movement difficulties.

Institutions must identify, quantify, and implement vari-ous measures to evaluate performance and promote contin-uous improvement throughout the university. IT can explicitly and implicitly be part of those objectives or part of measuring and evaluating performance.

RELATED TO BUDGETARY, FINANCIAL, AND MARKET ISSUES

Web-based resources are important tools used to attract stu-dents to an institution of higher learning. Data obtained from university web pages may be the first exposure that a prospective student has to the institution. An attractive, informative, and easy to maneuver set of webpages is essential in marketing to potential students and may influ-ence their selection of institution. The information provided could enhance each student’s decision-making process with key facts such as tuition cost, student graduation rate, and student retention comparisons between the institution and rivals.

Over the years, IT resources have continued to grow in usage by many entities. The most obvious reasons for IT explosion in organizations are its abilities to reduce cost and make data more easily and quickly accessible to a wide group of users. Cost savings come over time and usually result from reduction of human labor to complete a task. Having one data set from which all users can draw will improve data accuracy, reduce duplication of effort, reduce total amount of data stored, and eventually reduce cost.

CONCLUSIONS

This article proposes aligning IT resources of an educa-tional institution with the BSC-type results criteria of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award in Education. Educational institutions are different from businesses and typical governmental agencies so their IT resources need a unique evaluation tool. However, other entities should con-sider the importance of IT resources to reaching goals, improving results, and enhancing long-term sustainability.

This proposal emphasizes the reliance of educational institution on their IT resources in aligning plans, processes, decisions, people, actions, and results. Recognizing the mul-tiple impacts of IT acquisition, implementation, and assess-ment on educational institutions is essential. IT acquisition requires more than a traditional capital budgeting analysis.

Higher education institutions demand that the IT system increasingly delivers a portion of the institution’s primary objectives of promoting and demonstrating student learning and stakeholder satisfaction. The most significant contribu-tion of this article is the linking of IT resources used in an educational institutional to the specific criteria outcome areas of the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award in Education. Action to identify measures and targets in each of the results categories should be undertaken by specific institutions with their mission, values, and strategies in mind.

REFERENCES

Al-Zwyalif, I. (2012). The possibility of implementing balanced scorecard in Jordanian private universities. International Business Research, 5

(11), 113–120.

Baldrige National Quality Program. (2009).2009–2010 education criteria for performance excellence. Gaithersburg, MD: Author.

Baldrige National Quality Program. (2013).2013–2014 Education criteria for performance excellence. Gaithersburg, MD: Author.

Ball, L. D., & R. G Harris. (1982). SMIS members: A membership analy-sis.MIS Quarterly,6(1), 19–38.

Barclay, C. (2008). Toward an integrated measurement of IS project per-formance: The project performance scorecard. Information Systems Frontiers,10, 331–345.

Beard, D. (2009). Successful application of the balanced scorecard in higher education.Journal of Education for Business,11, 275–282. Brancheau, J. C., & Wetherbe, J. C. (1987). Key issues in information

sys-tems management.MIS Quarterly,11(1), 23–45.

Bremser, W. G., & White, L. F. (2000). An experimental approach to learning about the balanced scorecard.Journal of Accounting Education,

18, 241–255.

Brynjolfsson, E., & Hitt, L. (1995). Information technology as a factor of production: The role of differences among firms.Economics of Innova-tion and New Technology,3, 183–200.

Brynjolfsson, E., & Yang, S. (1996). Information technology and produc-tivity: A review of the literature.Advances in Computers,43, 179–214. Chandler, J. S. (1982). A multiple criteria approach for evaluating

informa-tion systems.MIS Quarterly,6, 61–74.

Chang, O. H., & Chow, C. W. (1999). The balanced scorecard: A potential tool for supporting change and continuous improvement in accounting education.Issues in Accounting Education,1, 395–412.

Chen, S. H., Yang, C. C., & Shiau, J. Y. (2006). The application of the bal-anced scorecard in the performance evaluation of higher education.The TQM Magazine,18, 190–205.

Cullen, J., Joyce, J., Hassall, T., & Broadbent, M. (2003). Quality in higher education: From mentoring to management.Quality Assurance in Edu-cation,2, 1–5.

Dickson, G. W., Leistheser, R. L., Wetherbe, J. C., & Nechis, M. (1984). Key information systems issues for the 1980’s.MIS Quarterly,8, 135– 159.

Hafner, K. A. (1998).Partnership for performance: The balanced score-card put to the test at the University of California. Retrieved from http:// www.ucop.edu/ucophome/businit/10-98-bal-scor-chapter.pdf

Hoffecker, J., & Goldenberg, C. (1994). Using the balanced scorecard to develop companywide performance measures.Journal of Cost Manage-ment,8(3), 5–17.

Kamhawi, E. (2011). IT and non-IT factors influencing the adoption of BSC systems: A Delphi study from Bahrain.International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management,60, 464–492.

ALIGNMENT OF UNIVERSITY IT RESOURCES 387

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard-measures that drive performance.Harvard Business Review,70(1), 71–79. Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1993). Putting the balanced scorecard to

work.Harvard Business Review,71(5), 134–142.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996a). Translating strategy into action: the balanced scorecard. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996b). Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system.Harvard Business Review,74(1), 75–85. Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (2001). On balance.CFO,17, 73–78. Karathanos, D., & Karathanos, P. (2005). Applying the balanced scorecard

in education.Journal of Education for Business,80, 222–230.

Kim, D., Yue, K., Al-Mubaid, H., Hall, S., & Abeysekera, K. (2012). Assessing information systems and computer information systems pro-grams from a balanced scorecard perspective.Journal of Information Systems Education,23, 177–192.

Maisel, L. S. (1992). Performance measurement: The balanced scorecard approach.Journal of Cost Management,6(2), 47–52.

Newing, R. (1994). Benefits of a balanced scorecard.Accountancy,114

(1215), 52–53.

Newing, R. (1995). Wake up to the balanced scorecard. Management Accounting,73(3), 22–23.

Papenhausen, C., & Einstein, W. (2006). Implementing the balanced scorecard at a college of business.Measuring Business Excellence,103(3), 15–22. Parker, M. M., Benson, R. J., & Trainor, H. E. (1988).Information

eco-nomics: Linking business performance to information technology. Eng-lewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Ruben, B. D. (1999). Toward a balanced scorecard of higher educa-tion: rethinking the college and universities excellence indicators of

framework. Higher Education Forum, QCI, Center for Organiza-tional Development and Leadership, Rutgers University. Retrieved from http://dfcentre.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Balanced-Scorecard-in-Higher-Education.pdf

Schobel, K., & Scholey, C. (2012). Balanced scorecards in education: Focusing on financial strategies.Measuring Business Excellence,16(3), 17–28.

Sethi, V., & King, W. R. (1994). Development of measures to assess the extent to which an information technology application provides compet-itive advantage.Management Science,40, 1601–1627.

Sinan, A., Brynjolfsson, E., & Van Alstyne, M. W. (2006).Information, technology and information worker productivity: Task level evidence. MIT Center for Digital Business Working Paper, October.

Sutherland, T. (Summer, 2000). Designing and implementing an academic scorecard.Accounting Education News, 11–13.

Tallon, P. P., Kraemer, K. L., & Gurbaxani, V. (2000). Executives’ perceptions of the business value of information technology: A process-oriented approach. Journal of Management Information Systems,16, 145–173.

Umashankar, V., & Dutta, K. (2007). Balanced scorecards in managing higher education institutions: An Indian perspective.International Jour-nal of EducatioJour-nal Management,21, 54–67.

Umayal, K., & Suganthi, L. (2010). A strategic framework for manag-ing higher educational institutions.Advances in Management,3(10), 15–21.

Violino, B. (1997). Return on investment.Information Week,30, 36–40. Ward, J. M. (1990). A portfolio approach to evaluating information

sys-tems investments and setting priorities.Journal of Information Technol-ogy,5, 222–231.