Ž .

Applied Animal Behaviour Science 66 2000 119–133

www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Does pecking at inanimate stimuli predict

cannibalistic behaviour in domestic fowl?

Sylvie Cloutier

), Ruth C. Newberry, Carrie T. Forster,

Katherine M. Girsberger

Center for the Study of Animal Well-being, Department of Veterinary and ComparatiÕe Anatomy,

Pharmacology and Physiology, Washington State UniÕersity, PO Box 646520, Pullman, WA 99164-6520, USA Accepted 24 June 1999

Abstract

We assessed the pecking behaviour of caged White Leghorn hens towards feather-shaped

Ž . Ž . Ž

stimuli varying in colour red or blue , material paper or feather and movement stationary or

.

movable attached to a board placed in the feed trough. Each of the eight stimulus combinations was presented to two replicate groups of 5 young hens for 15 min at 45 and 57 days of age. We predicted that the birds would be especially attracted to red movable feathers simulating a live bird

Ž .

with bloodstained feathers. Severe forceful pecks were directed more frequently at feather than

Ž . Ž .

paper stimuli P-0.05 and at movable than stationary stimuli P-0.01 but there was no differential response to red and blue stimuli. We reassessed responses to the stimuli by a subset of the original birds, now in 16 groups of four hens, at 696 and 710 days of age. We found no significant effects of colour, material or movement on the latency to peck the stimuli, or the frequency of gentle and severe pecks at the stimuli, indicating that responses to the stimulus characteristics were not consistent between young and old hens. There was a positive correlation between the frequency of severe feather pecking at flock mates and the frequency of cannibalistic

Ž .

behaviour P-0.01 , consistent with reports that bleeding resulting from feather pecking can lead to cannibalism. We found no significant correlation between the frequency of pecking at the inanimate stimuli and the frequencies of pecking at the flesh and feathers of flock mates. This analysis does not take into account possible behavioural differences between primary cannibals that drew blood and secondary cannibals that joined a cannibalistic attack once blood had been drawn. We conclude that the frequency of pecking at inanimate stimuli was not a good predictor of future cannibalistic behaviour by the hens in this study. However, a tendency for future cannibals and severe feather peckers to have longer latencies to peck the inanimate stimuli

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q1-509-335-2956; fax:q1-509-335-4650; E-mail: [email protected]

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

( ) S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 120

warrants further investigation. It will be possible to use responses to specific types of inanimate stimuli to predict cannibalistic tendencies only if future cannibals are found to have stable responses to those stimuli over time.q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Laying hens; Chicken; Feather pecking; Cannibalism; Social behaviour; Colour preference

1. Introduction

Cannibalism involves the pecking and tearing of skin and underlying tissues of another bird. It is a serious welfare problem in egg laying strains of the domestic fowl

ŽAppleby et al., 1988; Curtis and Marsh, 1992; reviewed by Yngvesson, 1997 and in.

Ž . Ž .

other poultry species including turkeys Newberry, 1992 , pheasants Cain et al., 1984

Ž .

and Muscovy ducks Martin, 1991 .

Ž

Cannibalism is one of the main causes of mortality in laying hens Appleby and .

Hughes, 1991 and, even if a pecked bird survives the attack, the wounds provide a route

Ž .

for infection that may lead to subsequent mortality Randall, 1977 .

Feather pecking is another debilitating behaviour performed by poultry. Feather pecking involves the destruction or removal of feathers of other birds, sometimes including consumption of the feathers. Removal of feathers is painful for the victim

ŽGentle and Hunter, 1991 and feather loss impairs thermoregulatory and flying ability..

Ž

Birds that perform feather pecking are not necessarily cannibalistic Keeling and Jensen, .

1994 . However, bleeding associated with feather breakage or removal during bouts of Ž

feather pecking behaviour has been reported to stimulate cannibalism Hughes and .

Duncan, 1972; Cuthbertson, 1978 .

Beak trimming is the main technique used to control cannibalism and feather pecking in poultry. The procedure is performed without anaesthetic, and there is behavioural and

Ž

neurological evidence that it can cause both acute and chronic pain Duncan et al., 1989; .

Gentle et al., 1990; Glatz et al., 1992 . Vision impairment through the use of dim

Ž .

lighting 1 lux or less , coloured contact lenses or genetically blind birds can be used to control cannibalism and feather pecking but this approach is also questionable. Vision

Ž .

impairment inhibits activity Newberry et al., 1988 . In laying hens, low activity is associated with osteopenia and a high risk of bone breakage during pre-slaughter

Ž .

handling Newberry et al., 1999 . There is a need to develop methods to control cannibalism and feather pecking that do not compromise poultry welfare in other ways.

Ž .

Specific individuals in a flock are cannibalistic Keeling, 1994 and birds with a

Ž .

tendency to peck others early in life maintain this characteristic Cuthbertson, 1978 . The incidence of cannibalism has been lowered through group selection for survivability

ŽMuir, 1996 . In other words, birds in groups with high mortality due to beak-inflicted.

injuries are excluded from the breeding flock. If the tendency to engage in cannibalistic or feather pecking behaviour is highly correlated with pecking behaviour towards specific inanimate stimuli early in life, this information could be used to select against cannibalism and feather pecking without waiting until this harmful behaviour occurs.

( )

S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 121

was to determine whether pecking behaviour directed towards these stimulus features is predictive of, or correlated with, cannibalistic or feather pecking behaviour directed towards live birds. We assessed the pecking behaviour of the birds towards inanimate

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

stimuli varying in: 1 colour red or blue , 2 material paper or feather and 3

Ž .

movement stationary or movable . We hypothesised that the tendency to peck inanimate stimuli is correlated with a tendency to peck the flesh and feathers of live birds. We predicted that birds would be especially attracted to red movable feathers simulating a live bird with bloodstained feathers. We also predicted that birds that performed cannibalism or feather pecking behaviour would perform severe pecks at the test stimuli more frequently and with a shorter latency than birds that did not participate in cannibalism or feather pecking events.

Our third objective was to determine whether pecking behaviour directed at inanimate stimuli is consistent over time. If pecking at inanimate stimuli increases with increased experience of cannibalistic events, this learning effect would reduce the efficacy of a selection program based on the pecking responses of young birds. Therefore, pecking behaviour was assessed in two experiments, one when the birds were between 6 and 9 weeks of age and a second when they were between 99 and 102 weeks of age.

2. Experiment 1

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Animals and husbandry

We housed 80 female White Leghorn chicks with intact beaks, obtained from a primary breeding company, in 16 groups of five birds. At 5 weeks of age, the groups

were transferred from brooder units to grow-out cages measuring 91 cm long=45 cm

Ž .

wide=37 cm high. Food standard pullet mash was provided ad libitum in an external

Ž .

trough 91 cm long=14 cm wide=9 cm high . Water was available ad libitum from

two cup-drinkers per cage. A sand bath was placed in each cage twice weekly to accommodate dust bathing behaviour. The duration of the photoperiod was 10 h and the

average light intensity at the level of the feeders was 83"7.7 lux.

At 16 weeks of age, a subset of the birds was transferred to solid-sided layer cages

measuring 125 cm long=40 cm wide=40 cm high. They were housed in 16 groups of

Ž .

four birds. Food standard layer diet was provided ad libitum from a feed trough

measuring 125 cm long=14 cm wide=10 cm high. Water was available ad libitum

from four cup-drinkers at the back of each cage. A sand bath was provided on three days per week. The duration of the photoperiod was 11.5 h and the average light intensity at

the level of the feeder was 195"20.4 lux.

( ) S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 122

2.1.2. Experimental treatments

We assessed the pecking behaviour of the birds in each group towards five identical, Ž

equally spaced stimuli attached in a row across a pale wooden board 80 cm long=27

.

cm high=1 cm thick . The board was placed at an angle with the base in the feed

trough, 4 cm from the cage front, and the top 30 cm out from cage front. A wire extending from each top corner was hooked onto the cage front to hold the board in place. The birds had to extend their heads about 11 cm out of the cage to peck the

Ž . Ž

stimuli. Between treatments, the stimuli varied in colour red or blue , material feathers

. Ž .

or paper and movement moveable or fixed in a 2=2=2 factorial design. Two

groups of birds were randomly assigned to each of these eight treatments.

For the feather stimuli, we autoclaved white chicken contour feathers of about 9 cm long and 4.5 cm wide. Half of the feathers were coloured a shade of red similar to fresh arterial blood and the other half were coloured blue. As done in previous research on the

Ž .

responses of pheasants to blood Jones and Faure, 1983 , the colour blue was used as a control for responses to the colour red. Red and blue are the colours that elicit most

Ž .

pecking and approach by day-old chicks Rogers, 1995 . However, this preference may be modified by later experiences as suggested by the variation in colour preferences

Ž .

reported for older birds in the literature e.g., Jones and Carmichael, 1998 . The feathers Ž

were dyed using a combination of clothing dye RIT — CPC International, Indianapolis,

. Ž .

IN, USA , food colouring Schilling —McCormick, Hunt Valley, MD, USA and

Ž .

permanent non-toxic marker Marks-a-lot — Avery Dennison, Framingham, MA, USA to saturate the feathers with the desired colour.

Ž . Ž .

For the paper stimuli, we used red Pro 0699-03 and blue Pro 0674-03 construction

Ž .

paper Pro Art, Beaverton, OR, USA selected to match the feather colours. A trace of a typical contour feather served as a template for the shape and size of the paper stimuli.

Ž .

The movable stimuli feather and paper were tied to the board at the proximal end of the rachis using white nylon string, 9 cm long, so that they hung loosely against the board. The stationary stimuli were glued to the board using a non-toxic washable glue

Ž .

stick Glue Stic — Avery Dennison, Framingham, MA, USA so that they were solidly fixed and did not move. Each stimulus was clearly contrasted against the pale wooden background.

2.1.3. BehaÕiour obserÕations

In Week 6, each group was given a 90-min acclimation session with the stimuli to Ž

reduce novelty that could lead to avoidance of the stimuli Jones and Black, 1979; Jones .

and Faure, 1981 . In the acclimation session, all groups were presented with a wooden

Ž .

board displaying all eight types of stimulus one stimulus from each treatment . At 45 days of age, each group was presented with a board displaying five identical stimuli of the same treatment for a 15-min period. The pecking behaviour of the birds towards the

Ž .

stimuli was recorded using a Hi8 camcorder Sony, Tokyo, Japan . Groups were tested sequentially in a pre-determined random order. They were tested again with the same treatment at 57 days of age but in a different random order. Birds were unable to inspect or peck at stimuli presented to neighbouring groups.

For each 15-min video recording, starting when the board was placed in the trough, Ž .

( )

S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 123

Ž . Ž . Ž .

to a put the head out of the cage eyes beyond the cage front , b peck at a stimulus,

Ž . Ž .

and c peck at the wooden board, 2 the number of severe pecks directed at the stimuli,

Ž .3 the number of gentle pecks directed at the stimuli, and 4 the number of pecksŽ .

directed at the wooden board. Severe pecks were hard pecks with a gripping, and pulling, ripping or tearing motion. They could be accompanied by lateral movement of the head as the bird held and shook a stimulus. When directed at a movable stimulus, they caused the stimulus to be lifted from the board and moved by the beak. When directed at a stationary stimulus, they resulted in the peeling or tearing of the stimulus, or parts thereof, from the board. Severe pecks would likely cause damage if directed at

Ž the skin or feathers of a live bird. Gentle pecks involved non-damaging contacts taps,

.

wipes, nibbles of the beak against a stimulus. They appeared to lack the force that would be needed to break skin or feathers, or to remove the feathers, of a live bird.

Relationships between pecking behaviour at the inanimate stimuli on the board and the cannibalistic and feather pecking tendencies of the birds were assessed. The

Ž . Ž

cannibalism frequencies for the periods from a 1 to 44 days of age before Experiment

. Ž . Ž .

1 and b 58 to 695 days of age between Experiment 1 and Experiment 2, see below were determined. A bird was considered to have performed cannibalism whenever she was found with blood on her beak at the time of a cannibalistic incident or observed pecking at a wound on another bird. Any injurious attack, even when it caused only very minor blood loss, was reported as a cannibalistic event. Groups in which cannibalism occurred were, thus, composed of a combination of cannibals, victims and neutral hens not observed to have participated in any cannibalistic attack. Data on feather pecking

Ž were collected between 76 and 90 weeks of age. Gentle and severe feather pecks as

.

defined above were recorded during six 10-min observation sessions while the birds

Ž .

were competing for a limited amount of canned cat food 15 g per bird placed in the feed trough. Feather pecks were also recorded during six 15-min observation sessions while the birds were competing for access to the sand bath. Severe and gentle feather pecks were distinguished from aggressive pecks in which a bird raised her head and delivered one or more hard, rapid stabs with the beak at another bird, usually at the head region. The total numbers of gentle and severe pecks given by each bird over the 150 min of observation were calculated.

2.1.4. Statistical analysis

A correlation analysis was performed to assess the stability of the response to the stimuli between the tests at 45 and 57 days of age. Analysis of treatment effects on pecking responses towards the inanimate stimuli was based on group means for 45 and 57 days combined. A square root transformation was applied to all frequency and latency variables except the gentle peck counts. They required log transformation to conform to the normality assumption of parametric statistics. We used the general linear

Ž . Ž .

( ) S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 124

2.2. Results — Experiment 1

We examined the intra-individual stability of the pecking and approach responses to the stimuli and board between 6 and 9 weeks of age. The responses at the two ages were

Ž .

significantly correlated 0.25FrF0.65, pF0.02 , indicating that the birds’ responses

remained relatively stable over the period between the tests. We, therefore, pooled the data from the two ages in subsequent analyses.

The latencies to put the head out of the cage and to peck at the wooden board were not significantly affected by stimulus colour, material, movement or their interactions

ŽF1,8F2.38, p)0.1, Table 1 . There was a non-significant trend for a shorter latency.

Ž . Ž

to peck feather stimuli 164"49.3 s than paper stimuli 314"79.2 s; F1,8s3.98,

. Ž . Ž

ps0.081 , and to peck movable stimuli 141"23.8 s than stationary stimuli 337"

.

83.6 s; F1,8s4.99, ps0.056 .

Ž .

Severe pecks were directed more often at feather stimuli 7"1.9 than paper stimuli

Ž2"1.2, F1,8s6.98, ps0.03 and at moving stimuli 8. Ž "1.7 than stationary stimuli. Ž2"1.1, F1,8s10.7, ps0.01 . There was no interaction between movement and.

Ž .

material for severe pecks F1,8s0, ps0.98 . Gentle pecks were directed more

Ž . Ž

frequently at feather stimuli 26"8.3 pecks per bird than paper stimuli 10"3.0;

.

F1,8s6.94, ps0.03 . This effect was primarily due to the relatively low number of

Ž

gentle pecks directed at the stationary paper stimuli 4"0.5, Ryan–Einot–Gabriel–

. Ž .

Welsch multiple range test compared to the movable paper 16"3.8 , stationary

Ž . Ž . Ž .

feather 36"15.6 and movable feather 16"3.4 stimuli F1,8s6.35, ps0.036 .

Ž

Colour had no significant effect on the frequency of gentle pecks blue: 17.8"4.61;

. Ž .

red: 18.3"8.60 or severe pecks blue: 5.1"1.87; red: 4.32"1.74 at the stimuli

ŽF1,8F0.17, p)0.1 . The frequency of pecks to the board was not affected by the.

Ž .

characteristics of the attached stimuli F1,8F0.79, p)0.1, Table 1 .

There were 18 cannibalistic attacks on a total of 16 different birds between 1 and 44 days of age. These attacks occurred in eight of the 16 groups. There were 111 cannibalistic attacks on 49 different birds between 58 and 695 days of age. During this period, 31 birds participated in at least one cannibalistic attack and cannibalism occurred

in 15 of the 16 groups. An average of 8.0"2.19 severe, and 6.2"1.02 gentle, feather

pecks occurred per bird per 150 min when the birds were competing for cat food and the sand bath.

There were positive correlations between the latencies to put the head out of the cage,

Ž .

()

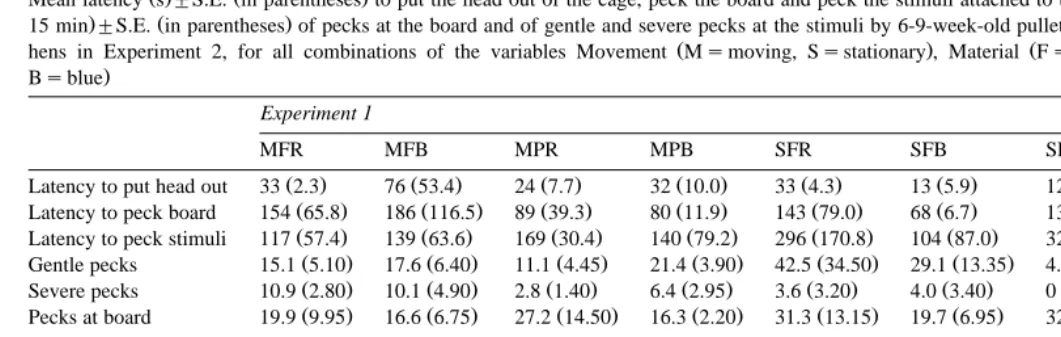

Mean latency s"S.E. in parentheses to put the head out of the cage, peck the board and peck the stimuli attached to the board, and mean frequency per bird per

. Ž .

15 min"S.E. in parentheses of pecks at the board and of gentle and severe pecks at the stimuli by 6-9-week-old pullets in Experiment 1 and by 99–102-week-old

Ž . Ž . Ž

hens in Experiment 2, for all combinations of the variables Movement Msmoving, Ssstationary , Material Fsfeather, Pspaper and Colour Rsred,

.

Bsblue

Experiment 1

MFR MFB MPR MPB SFR SFB SPR SPB Total

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency to put head out 33 2.3 76 53.4 24 7.7 32 10.0 33 4.3 13 5.9 127 113.8 43 5.8 48 14.6

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency to peck board 154 65.8 186 116.5 89 39.3 80 11.9 143 79.0 68 6.7 138 116.2 154 77.7 126 22.0

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency to peck stimuli 117 57.4 139 63.6 169 30.4 140 79.2 296 170.8 104 87.0 326 133.4 622 62.8 239 49.0

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Gentle pecks 15.1 5.10 17.6 6.40 11.1 4.45 21.4 3.90 42.5 34.50 29.1 13.35 4.6 0.60 3.0 0.05 18.0 4.71

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Severe pecks 10.9 2.80 10.1 4.90 2.8 1.40 6.4 2.95 3.6 3.20 4.0 3.40 0 0 4.7 1.24

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Pecks at board 19.9 9.95 16.6 6.75 27.2 14.50 16.3 2.20 31.3 13.15 19.7 6.95 32.0 21.20 23.5 8.05 23.3 3.38

Experiment 2

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency to put head out 458 91.7 186 59.8 362 346.8 245 72.9 228 171.8 345 89.2 194 26.1 336 275.6 294 51.3

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency to peck board 849 51.1 627 1.3 613 208.3 635 33.4 732 88.0 868 32.3 647 108.2 654 243.1 703 40.8

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency to peck stimuli 792 107.6 900.0 0 712 188.0 638 19.8 780 110.6 831 69.0 696 91.8 740 159.6 761 36.5

()

S.

Cloutier

et

al.

r

Applied

Animal

Beha

Õ

iour

Science

66

2000

119

–

133

126

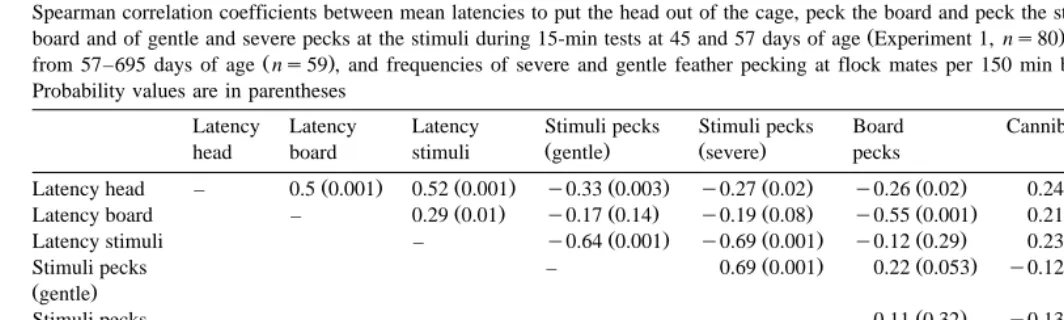

Table 2

Spearman correlation coefficients between mean latencies to put the head out of the cage, peck the board and peck the stimuli, and mean frequencies of pecks at the

Ž .

board and of gentle and severe pecks at the stimuli during 15-min tests at 45 and 57 days of age Experiment 1, ns80 , frequencies of participation in cannibalism

Ž . Ž .

from 57–695 days of age ns59 , and frequencies of severe and gentle feather pecking at flock mates per 150 min between 536 and 624 days of age ns59 . Probability values are in parentheses

Latency Latency Latency Stimuli pecks Stimuli pecks Board Cannibalism Feather pecks Feather pecks

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

head board stimuli gentle severe pecks severe gentle

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency head – 0.5 0.001 0.52 0.001 y0.33 0.003 y0.27 0.02 y0.26 0.02 0.24 0.07 0.24 0.07 0.06 0.67

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency board – 0.29 0.01 y0.17 0.14 y0.19 0.08 y0.55 0.001 0.21 0.11 0.29 0.03 y0.06 0.64

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency stimuli – y0.64 0.001 y0.69 0.001 y0.12 0.29 0.23 0.08 0.23 0.09 0.04 0.77

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Stimuli pecks – 0.69 0.001 0.22 0.053 y0.12 0.38 y0.12 0.36 y0.18 0.16

Žgentle.

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Stimuli pecks – 0.11 0.32 y0.13 0.33 y0.20 0.12 y0.11 0.40

Žsevere.

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Board pecks – y0.14 0.29 y0.14 0.29 0.05 0.71

Ž . Ž .

Cannibalism – 0.33 0.01 y0.16 0.23

Ž .

Feather pecks – 0.30 0.02

Žsevere.

Feather pecks –

( )

S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 127

We did not identify all participants in early cannibalistic events. However, we did find that, on average, birds in groups that experienced at least one cannibalistic event prior to testing at 45 days directed fewer gentle and severe pecks at the inanimate

Ž

stimuli than birds in groups without cannibalism prior to testing gentle pecks: 14.2"

2.67 vs. 21.9"5.14, respectively, ts5.5, dfs14, p-0.001; severe pecks: 3.6"1.02

.

vs. 5.8"1.08, respectively, ts3.1, dfs14, p-0.01 .

2.3. Discussion — Experiment 1

Severe pecks were directed more frequently at feather than paper stimuli and at movable than stationary stimuli, possibly because the feathers and movable stimuli were easier to grasp and manipulate. Feathers may have been more attractive than the flat paper stimuli because they were more familiar, more complex, more easily torn, and more edible. When glued to the board, the uneven surface of the feathers allowed the birds to grip and tear pieces of feather away from the board whereas this was almost impossible with the stationary paper stimuli. Some birds were observed ‘‘chewing’’ following pecks at feathers whereas this behaviour was not observed with paper stimuli. Under free range conditions, domestic fowl chase and capture live prey such as mice and

Ž .

flying insects Newberry, personal observations, 1995; Rogers, 1995 , possibly provid-ing an additional explanation as to why the young hens performed more severe pecks at movable than stationary stimuli.

Although the birds were attracted to movable feathers, our prediction that they would be especially attracted to red movable feathers was not supported by the data. However,

Ž .

given the low sample size used Ns2 groups , further study would be needed to detect

subtle differences in attraction to red movable feathers, especially if only a subset of

Ž .

birds e.g., cannibals might be differentially attracted to such stimuli. In the current work, red and blue stimuli received similar numbers of pecks, suggesting either that colour was not a key feature triggering pecking behaviour or that both blue and red were equally effective in triggering pecking behaviour. The absence of a colour effect suggests that the red colour of fresh blood is not a significant factor in initiating

Ž

cannibalism. In cannibalism, the contrast between blood and feathers especially white .

feathers , or the smell, taste or sheen of fresh blood may be of greater relevance than the colour. The absence of treatment effects on latency to put the head out of the cage,

Ž

latency to peck the board and frequency of pecks at the board within several

.

centimetres of the stimuli suggests that the birds were not differentially fearful of the stimuli.

( ) S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 128

Our hypothesis that severe pecks at inanimate stimuli would be correlated with cannibalism and feather pecking at flock mates was not supported by the data. Contrary to our prediction, birds that subsequently performed cannibalism or feather pecking behaviour did not perform severe pecks at the test stimuli more frequently or with a shorter latency than birds that did not participate in cannibalism or feather pecking events. Future cannibalism and severe feather pecking actually tended to be correlated with longer latencies to approach and peck the inanimate stimuli. Also, birds in groups that had already experienced cannibalism performed fewer pecks at the inanimate stimuli than birds in groups that had not experienced cannibalism.

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Methods

Experiment 2 was conducted to determine whether the pecking responses towards inanimate stimuli observed in Experiment 1 were consistent with pecking responses when the birds were older. The birds were acclimated to the stimulus board during Week 99. Their pecking responses to the inanimate stimuli were assessed at 696 and 710 days of age using the same methods as in Experiment 1 except that there were eight, instead of five, identical stimuli on the board. Not all birds were in their original groups. Therefore, a new random assignment of groups to treatments was used. The data on latency to put the head out of the cage and latency to peck the board were analysed as in Experiment 1. The remaining variables were not normally distributed even after transformation. The Rank procedure was applied to these data prior to analysis using the

Ž .

GLM procedure of the SAS Institute 1989 .

3.2. Results — Experiment 2

The pecking and approach responses to the stimuli and board remained relatively

Ž .

stable between the tests at 99 and 102 weeks of age 0.30FrF0.45, pF0.02 and so

we pooled the data from the two tests in subsequent analyses.

By the start of Experiment 2, cannibalism had occurred in all but one of the groups. However, this increased experience of cannibalism was not associated with increased pecking at the inanimate stimuli. The adult hens were much less responsive to the board and attached stimuli than they had been when young. There was no increase in attraction to the colour red. None of the latency or frequency variables were significantly affected

Ž

by the stimulus colour, material, movement or their interactions F1,8F2.98, p)0.1,

. Table 1 .

Comparison of pecking responses to the inanimate stimuli in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 revealed only two significant Spearman correlations. Birds that had pecked more frequently at the board in Experiment 1 had a shorter latency to peck the

Ž . Ž

board rs y0.27, ps0.04 , and pecked the board more frequently rs0.26, ps

.

()

S.

Cloutier

et

al.

r

Applied

Animal

Beha

Õ

iour

Science

66

2000

119

–

133

129

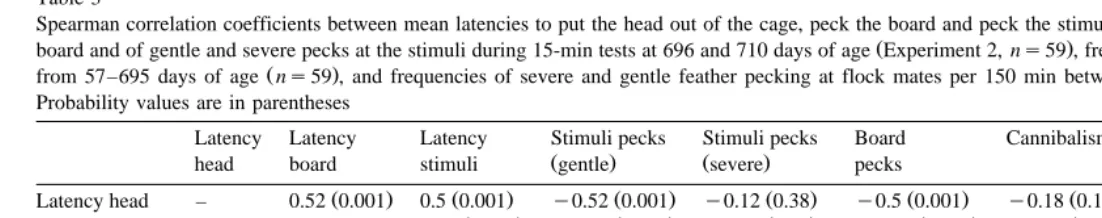

Table 3

Spearman correlation coefficients between mean latencies to put the head out of the cage, peck the board and peck the stimuli, and mean frequencies of pecks at the

Ž .

board and of gentle and severe pecks at the stimuli during 15-min tests at 696 and 710 days of age Experiment 2, ns59 , frequencies of participation in cannibalism

Ž . Ž .

from 57–695 days of age ns59 , and frequencies of severe and gentle feather pecking at flock mates per 150 min between 536 and 624 days of age ns59 . Probability values are in parentheses

Latency Latency Latency Stimuli pecks Stimuli pecks Board Cannibalism Feather pecks Feather pecks

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

head board stimuli gentle severe pecks severe gentle

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency head – 0.52 0.001 0.5 0.001 y0.52 0.001 y0.12 0.38 y0.5 0.001 y0.18 0.18 0.02 0.88 0.04 0.77

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency board – 0.55 0.001 y0.53 0.001 y0.04 0.74 y0.94 0.001 y0.18 0.17 y0.14 0.31 y0.07 0.63

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Latency stimuli – y0.98 0.001 y0.41 0.001 y0.53 0.001 0.03 0.81 y0.05 0.69 y0.06 0.66

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Stimuli pecks – 0.41 0.001 0.51 0.001 y0.09 0.51 0.06 0.68 0.05 0.71

Žgentle.

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Stimuli pecks – 0.06 0.64 y0.04 0.76 0.10 0.45 0.09 0.5

Žsevere.

Ž . Ž . Ž .

( ) S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 130

As found in Experiment 1, there were positive correlations between the latencies to Ž put the head out of the cage, peck the board and peck the stimuli in Experiment 2 Table

.

3 . As these latencies increased, fewer pecks at the stimuli and the board were made per 15-min test. Birds that performed more gentle pecks at the stimuli also performed more severe pecks at the stimuli and more pecks at the board. The birds’ history of cannibalism and feather pecking at flock mates was not significantly correlated with their pecking frequencies at the inanimate stimuli in Experiment 2. However, birds that had participated in cannibalistic events tended to perform more pecks at the board.

3.3. Discussion — Experiment 2

The adult hens showed a relatively low response to the inanimate stimuli. This lack of responsiveness was also noticed during acclimation to the stimulus board in Week 99. At that time, we tried sprinkling some feed on the board and noticed that hens rapidly approached the board and pecked at the feed as it slid down the board into the feed trough. We saw no overt escape or freezing behaviour by the hens in the presence of the stimulus board. These informal observations suggest that the low rate of pecking at the stimuli by older birds was not due to increased fearfulness of the stimuli. Jones and

Ž .

Carmichael 1998 reported a higher frequency of pecking at inanimate stimuli by adult hens than we observed in this study. However, their hens were housed in individual cages from 16 weeks of age, thus limiting their exposure to cannibalism and feather

Ž .

pecking. Bessei et al. 1997 , who reported a correlation between the frequency of pecks at inanimate stimuli and feather pecks, also used hens housed individually from 26 weeks of age. Their results may not be applicable to group housed birds.

It is possible that the inanimate stimuli were no longer sufficiently novel to attract intrinsic exploration or that the older birds were less motivated to explore than the

Ž .

young hens. Newberry 1999 reported that broiler chickens showed peak responses to novelty at four to five weeks of age. We are not aware of any research on the ontogeny of exploration in domestic fowl over the age range of the present study.

The lack of correlation between responses to the inanimate stimuli between the two experiments is probably related to the reduced responsiveness of the older birds to the stimuli. This finding was also probably influenced by the fact that individual birds were not presented with the same treatment at both ages. The pecking responses of an individual specifically attracted to a stimulus characteristic that was presented in one experiment but not in the other would not be correlated. Although there were differences in housing conditions between the two experiments, these differences did not lead us to expect a lower responsiveness to the stimuli among the older birds. By contrast, the higher light intensity in the adult hen room might have been expected to favour a higher

Ž .

frequency of severe pecking at the stimuli Kjaer, 1998 .

4. General discussion

( )

S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 131 Ž

domestic fowl and pheasants Jones and Faure, 1981; Jones and Faure, 1983; Rogers, .

1995 . Young domestic fowl and pheasants tend to avoid blood upon first presentation

ŽJones and Black, 1979; Jones and Faure, 1981 suggesting that attraction to blood may.

be acquired secondarily to exposure to wounds resulting from feather pecking, fighting or accidental injury. Olfactory cues associated with blood contribute to its avoidance by

Ž .

chicks Jones and Black, 1979 . Chicks can learn to associate specific odours with

Ž .

specific colours and tastes Jones and Roper, 1997; Barnea et al., 1999 . The taste

ŽFraser, 1987 and odour of blood, and of lipids coating the feathers, may play an.

important role in the development of attraction to blood and feathers. Lipids would have been removed from our test feathers when they were autoclaved and dyed. Therefore, the stimuli in our study were not associated with the particular odour or taste of blood and feathers, which may explain why the adult hens were not attracted to the inanimate stimuli despite previous experience of cannibalism and feather pecking. By contrast,

Ž .

Yngvesson and Keeling 1998 found that adult hens pecked blood-stained feathers more frequently than unstained feathers in a preference test.

It has been suggested that feather peckers are more active birds that spend less time

Ž .

pecking at food and the environment Hughes, 1982 , or that they are more fearful birds

ŽVestergaard et al., 1993 , than non-feather peckers. If our feather pecking and cannibal-.

istic birds were more active or more fearful than their flock mates when young but not when older, this could explain the tendency for cannibalism and severe feather pecking to be correlated with longer latencies to inspect and peck at the stimuli and board in Experiment 1 but not in Experiment 2. However, this explanation is inconsistent with the lack of correlation between pecking frequencies at inanimate stimuli and live birds in

Ž .

either experiment. Jones et al. 1995 reported no difference in duration of tonic

immobility between high and low feather pecking lines of domestic fowl, thus suggest-ing that feather peckers are not more fearful. Our results are more consistent with the idea that birds that developed a search image for pecking the feathers or flesh of flock mates became less interested in pecking inanimate stimuli that differed in odour, taste and other characteristics.

Social learning may also have reduced correlations between responses to inanimate stimuli and flock mates. Fowl use information obtained from observing flock mates to

Ž

evaluate the quality of a feeding site McQuoid and Galef, 1992, 1993; Nicol and Pope, .

1994 . In social groups, birds have the potential to witness cannibalistic attacks and to

Ž .

become actively involved. Martin 1991 observed that, over a period of five days, all members of a flock of 100 Muscovy ducklings with intact beaks were injured by cannibalism and that increasing numbers of birds participated in the cannibalistic attacks. In our study, we could not distinguish between primary cannibals that drew blood and secondary cannibals that joined a cannibalistic attack once blood had been drawn. These birds may differ in their pecking behaviour towards inanimate stimuli. Also, the design of our study did not allow us to determine whether birds became differentially attracted to red moving feather stimuli after participating in cannibalistic attacks. Such a possibility awaits further research.

( ) S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 132

were not consistent between young and old hens. On the other hand, the greater latency of some future cannibals and severe feather peckers to approach and peck the stimuli and board may have predictive value and warrants further investigation. It is also possible that future cannibals respond differently than non-cannibals to inanimate stimuli having specific characteristics. To our knowledge, our study provides the first published data on the frequency of cannibalistic attacks made by individually-identified caged

Ž .

birds with intact beaks over an extended period two years and with all attacks

registered, not just deaths resulting from cannibalism.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to J. Courneen, B.L. Van Way, D. Jensen and B. Wheeler for animal care, J. Huyler and G. Van Orden for veterinary care, S. Dhillon and M. Knott for providing feathers, C.M. Ulibarri for scientific discussion and R. Alldredge for statistical advice. This material is based upon work supported by the Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service, US Department of Agriculture, under Agreement No. 97-35204-4812 to R.C. Newberry and C.M. Ulibarri, and by a Summer Grant for Veterinary Students from the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation to C.T. Forster and K.M. Girsberger.

References

Appleby, M.C., Hughes, B.O., 1991. Welfare of laying hens in cages and alternative housing systems: environmental, physical and behavioural aspects. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 47, 109–128.

Appleby, M.C., Hogarth, G.S., Anderson, J.A., Hughes, B.O., Whittemore, C.T., 1988. Performance of a deep litter system for egg production. Br. Poult. Sci. 29, 735–751.

Barnea, A., Gvaryahu, G., Rothschild, M., 1999. The effect of the odour of pyrazine and colours on recall of

Ž . Ž .

past events and learning in domestic chicks Gallus gallus domesticus . In: van Emden, H.F. Ed. , Insects and Birds. Chapman & Hall, London, UK, in press.

Bessei, W., Reiter, K., Schwarzenberg, A., 1997. Measuring pecking towards a bunch of feathers in individually housed hens as a means to select against feather pecking. In: Koene, P., Blockhuis, H.P.

ŽEds. , Proceedings of the 5th European Symposium on Poultry Welfare, Wageningen, The Netherlands,.

pp. 74–76.

Cain, J.R., Weber, J.M., Lockamy, T.A., Creger, C.R., 1984. Grower diets and bird density effects on growth and cannibalism in ring-necked pheasants. Poult. Sci. 63, 450–457.

Curtis, P.E., Marsh, N.W.A., 1992. Cannibalism in laying hens. Vet. Rec. 131, 424.

Cuthbertson, G.J., 1978. The development of feather pecking and cannibalism in chicks. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 4, 292.

Duncan, I.J.H., Slee, G.S., Seawright, E., Breward, J., 1989. Behavioural consequences of partial beak

Ž .

amputation beak trimming in poultry. Br. Poult. Sci. 30, 479–488.

Fraser, D., 1987. Mineral-deficient diets and the pig’s attraction to blood: implications for tail biting. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 67, 909–918.

Glatz, P.C., Murphy, L.B., Preston, A.P., 1992. Analgesic therapy of beak-trimmed chickens. Aust. Vet. J. 69, 18.

Gentle, M.J., Hunter, L.N., 1991. Physiological and behavioural responses associated with feather removal in Gallus gallus var domesticus. Res. Vet. Sci. 50, 95–101.

( )

S. Cloutier et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 66 2000 119–133 133

Ž .

Hughes, B.O., 1982. Feather pecking and cannibalism in domestic fowls. In: Bessei, W. Ed. , Disturbed Behaviour in Farm Animals. Verlag Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart, Germany, pp. 138–146.

Hughes, B.O., Duncan, I.J.H., 1972. The influence of strain and environmental factors upon feather pecking and cannibalism in fowls. Br. Poult. Sci. 13, 525–547.

Jones, R.B., Black, A.J., 1979. Behavioral responses of the domestic chick to blood. Behav. Neural Biol. 27, 319–329.

Ž .

Jones, R.B., Faure, J.-M., 1981. The effect of age on the responses of pheasants Phasianus colchicus to conspecific blood. IRCS Med. Sci. 9, 498–499.

Ž .

Jones, R.B., Faure, J.-M., 1983. A further analysis of the responses of pheasants Phasianus colchicus to conspecific blood. IRCS Med. Sci. 11, 955–956.

Jones, R.B., Roper, T.J., 1997. Olfaction in the domestic fowl: a critical review. Physiol. Behav. 62, 1009–1018.

Jones, R.B., Carmichael, N.L., 1998. Pecking at string by individually caged, adult laying hens: colour preferences and their stability. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 60, 11–23.

Jones, R.B., Blockhuis, H.J., Beuving, G., 1995. Open-field test and tonic immobility responses in domestic chicks of two genetic lines differing in their propensity to feather peck. Br. Poult. Sci. 36, 525–530. Keeling, L.J., 1994. Feather pecking — who in the group does it, how often and under what circumstances?

In: Proceedings of the 9th European Poultry Conference, Glasgow, Scotland. UK Branch, World’s Poultry Science Association, Andover, UK, pp. 288–289.

Keeling, L.J., Jensen, P., 1994. Do feather pecking and cannibalistic hens have different personalities? In: Proceedings of the 28th International Congress of the International Society for Applied Ethology, Foulum, Denmark. National Institute of Animal Science, Tjele Denmark, p. 105.

Kjaer, J.B., 1998. Light intensity affects physical activity and feather pecking in chickens. Poult. Sci. 77, 1843.

´

Martin, F., 1991. Evaluation de la pertinence de la pratique du debecage comme moyen de prevention du´ ´ ´

Ž .

picage et du cannibalisme chez le canard de Barbarie Cairina moschata eleve industriellement. MSc´ ´

thesis, Universite du Quebec a Montreal, Montreal, Canada.´ ´ ` ´ ´

Ž

McQuoid, L.M., Galef, B.G., 1992. Social influences on feeding site selection by Burmese fowl Gallus

.

gallus . J. Comp. Psychol. 106, 137–141.

McQuoid, L.M., Galef, B.G., 1993. Social stimuli influencing feeding behaviour of Burmese junglefowl: a video analysis. Anim. Behav. 46, 13–22.

Muir, W.M., 1996. Group selection for adaptation to multiple-hen cages: selection program and direct responses. Poult. Sci. 75, 447–458.

Newberry, R.C., 1992. Influence of increasing photoperiod and toe clipping on breast buttons of turkeys. Poult. Sci. 71, 1471–1479.

Newberry, R.C., 1999. Exploratory behaviour in young domestic fowl. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 63, 311–321. Newberry, R.C., Hunt, J.R., Gardiner, E.E., 1988. Influence of light intensity on the behavior and performance

of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 67, 1020–1025.

Newberry, R.C., Webster, A.B., Lewis, N.J., Van Arnam, C., 1999. Management of spent hens. J. Appl. Anim. Welfare Sci. 2, 13–29.

Nicol, C.J., Pope, J., 1994. Social learning in small flocks of laying hens. Anim. Behav. 47, 1289–1296. Randall, C.J., 1977. A survey of mortality in 51 caged laying flocks. Avian Pathol. 6, 149–170.

Rogers, L.J., 1995. The Development of Brain and Behaviour in the Chicken. CAB International, Tucson, USA.

SAS Institute, 1989. SASrSTAT User’s Guide, Version 6, 4th edn., Vol. 2. SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA. Vestergaard, K.S., Kruijt, J.P., Hogan, J.A., 1993. Feather pecking and chronic fear in groups of red junglefowl: their relations to dustbathing, rearing environment and social status. Anim. Behav. 45, 1127–1140.

Yngvesson, J., 1997. Cannibalism in laying hens. A literature review. Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Animal Environment and Health, Skara, Sweden. Yngvesson, J., Keeling, L.J., 1998. Are cannibalistic laying hens more attracted to blood in a test situation

Ž .