PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

On: 16 June 2010Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 907217933] Publisher Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Educational Studies

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713415834

Inducing mind sets in self-regulated learning with motivational

information

R. Martensa; C. de Brabanderb; J. Rozendaalb; M. Boekaertsb; R. van der Leedenc

a Open University of the Netherlands, Ruud de Moorcentrum, 6401 DL Heerlen, The Netherlands b

Department Education and Child Studies, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Leiden

University, 2300 RB Leiden, The Netherlands c Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social and

Behavioural Sciences, Leiden University, 2300 RB Leiden, The Netherlands

First published on: 21 January 2010

To cite this Article Martens, R. , de Brabander, C. , Rozendaal, J. , Boekaerts, M. and van der Leeden, R.(2010) 'Inducing

mind sets in self-regulated learning with motivational information', Educational Studies, 36: 3, 311 — 327, First published on: 21 January 2010 (iFirst)

To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/03055690903424915

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03055690903424915

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Vol. 36, No. 3, July 2010, 311–327

ISSN 0305-5698 print/ISSN 1465-3400 online © 2010 Taylor & Francis

DOI: 10.1080/03055690903424915 http://www.informaworld.com

Inducing mind sets in self-regulated learning with motivational

information

R. Martensa*, C. de Brabanderb, J. Rozendaalb, M. Boekaertsb and R. van der Leedenc

aOpen University of the Netherlands, Ruud de Moorcentrum, PO Box 2960, 6401 DL Heerlen,

The Netherlands; bDepartment Education and Child Studies, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Leiden University, PO Box 9555, 2300 RB Leiden, The Netherlands;

cDepartment of Psychology, Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Leiden University,

PO Box 9555, 2300 RB Leiden, The Netherlands Taylor and Francis

The way students perceive a learning climate (e.g. controlling or stimulating) is significantly influenced by feedback and assessment. However, at present much is unclear about the relation between feedback and motivational state. More specifically, the interplay with student characteristics is unclear. Since there is a strong increase of group work, the central research question is what are the effects of positive, neutral or negative feedback presented to collaborating teams of students, on students’ intrinsic motivation, performance and on group processes? One hundred thirty-eight higher education students participated in this study. There were no significant differences in performance across conditions. Multi-level analysis enabled a detailed comparison between groups and individual members of groups. Amongst others, it was found that feelings of competence facilitate the effect of positive feedback at the group level, which suggests that positive feedback boosts interest especially in groups of highly competent students.

Keywords: motivation; self-regulated learning; feedback; incentives; blended learning

Introduction

Often teachers complain that they are confronted with passive students who are reluctant to invest effort. Several researchers have shown that motivation generally decreases in the course of schooling (e.g. Groves 2005). There is a general concern that (intrinsic) motivation is low (e.g. Boekaerts and Martens 2006; Legault, Green-Demers, and Pelletier 2006; Manalo et al. 2006; Saab, van Joolingen, and van Hout-Wolters 2009; Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Soenens et al. 2004). Only with sufficient external pressure (such as exams, withholding study credits) some students can be set to work, whilst others appear motivated. Tsai et al. (2008) put it like this: “Five minutes before the end of a lesson, students may be waiting impatiently for the bell to ring or be so engaged in the lesson that they are quite unaware of the time” (460).

In view of these concerns, and the fact that new learning environments have to rely even more on motivated self-regulated learning, it is not surprising that in the past two decades there has been a strong, renewed interest in the study of motivation in relation to learning (Pintrich 2003; Simon 1995).

*Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

Self-regulated learning

In an attempt to transform students’ passive study behaviour into more active engage-ment, “new” learning concepts have emerged, such as independent learning, self-regulated learning, informal learning, active learning, problem-based learning and work-based learning. Several researchers have combined social constructivism and information and communication technology (ICT) which is sometimes referred to as “new learning” (Simons, van der Linden, and Duffy 2000).

Unfortunately, the theoretical underpinnings of many educational innovations are poor and definitions are vague (Boekaerts and Martens 2006; Martens, Bastiaens, and Kirschner 2007; Martens, Gulikers, and Bastiaens 2004; Stoof et al. 2002).

In order to find some common denominators, Simons, Van der Linden, and Duffy (2000) examined the innovations from the student perspective. They identified the following key features of social constructivism: students are capable of working rela-tively independent from teachers. They are expected to process the learning material at a deep level, explore and experiment, and show some curiosity. Apart from being meta-cognitively active, students need to show responsibility for the regulation of their own learning. They should also be capable and willing to motivate themselves for learning individually and collaboratively (Strijbos, Kirschner, and Martens 2004). Often realistic, authentic learning environments are created to evoke this type of motivation (Garris, Ahlers, and Driskell 2002). It is striking how this desired study behaviour seamlessly matches the study behaviour of students with a high intrinsic motivation (Boekaerts and Martens 2006). Ryan and Deci (2000) contrast intrinsic motivation with extrinsic motivation. The latter denotes the performance of an activity in order to attain a certain outcome whereas the former refers to doing an activity for the inherent satisfaction of the activity itself.

Research has shown that intrinsic motivation leads to specific outcomes. Intrinsi-cally motivated students are more curious, favour collaboration, and experience more positive emotions (e.g. Levesque et al. 2004; Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Soenens et al. 2004). They also exchange information more often with peers and are more explorative (Martens, Gulikers, and Bastiaens 2004). Hardre and Reeve (2003) pointed out that generally these students’ outperform their less intrinsically motivated peers (see also Ryan and Deci 2000). The key or main point we are making here is that the key features of social constructivism coincide with the behaviour that is displayed by intrinsically motivated students (cf. Järvelä and Volet 2004).

To date much evidence has accumulated which shows that intrinsic motivation can be fostered by creating a learning environment that students perceive as support-ing their three basic psychological needs, namely their need for autonomy (e.g. having choices and little external pressure such as grades; Reeve, Nix, and Hamm 2003), competence (e.g. having success experiences) and social relatedness (experi-encing a positive social climate). Ryan and Deci (2000) conceptualised the three basic psychological needs in their self-determination theory (SDT). Research in SDT has repeatedly confirmed that autonomously regulated behaviours are characterised by the experience of interest. By contrast, behaviours experienced as controlling are not associated with interest or task enjoyment. Accordingly, the level of autonomy support in the classroom is a key factor for understanding students’ interest. SDT is a macro-theory of human motivation concerned with the development and functioning of personality within social contexts. SDT is (implicitly) grounded in evolutionary psychology (Bjorklund and Pellegrini 2002) as it stresses that intrinsic motivation is

an evolved propensity. The theory focuses on the degree to which human behaviours are volitional or self-determined – that is, the degree to which people endorse their actions at the highest level of reflection and engage in the actions with a full sense of choice.

Intrinsic motivation consists of two constituents, namely positive emotion and interest. According to Hidi and Renninger (2006), interest experience is a psycholog-ical state that is characterised by an affective component of positive emotion and a cognitive component of concentration. When persons experience interest, their actions acquire an intrinsic quality; they are driven by enjoyment rather than external forces or reasons. Interest is central to both intrinsic motivation and autonomous forms of extrinsic motivation (Ryan and Deci 2000), and extreme forms of interest experience are sometimes referred to as “flow” (Tsai et al. 2008).

States of interest arise through an interaction between the person and the surround-ing context. Individual interest or personal interest is defined as a relatively endursurround-ing disposition to attend to certain objects, stimuli or events over time. However, situa-tional factors may also play a role in influencing students’ interest experience over and above individual characteristics. This study focuses on this surrounding, educational context.

Goals, motivational information, feedback and extrinsic incentives

Goals can be intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic goals include those for self-acceptance, affiliation, community feeling and physical health. In contrast, extrinsic goals are primarily concerned with obtaining some reward or social praise; they are typically a means to some other end or compensate for problems in need of satisfaction. These goals are less likely to be inherently satisfying. Financial success, social status and popularity are common extrinsic goals (Grouzet et al. 2005). By explaining to students that by studying a certain course they can reach a certain intrinsic goal, intrinsic motivation may be increased.

The problem however is that such extrinsic incentives can hinder intrinsic motiva-tion. After all, setting goals for students, even if they are meant to be intrinsic goals, may increase students’ perception of restricted autonomy. Recently published studies address the dilemma of how to give motivational information without making it an external incentive or creating pressure.

When we supply students with motivational information, we are not dealing with a continuous stream of information. It is information that is restricted in time and place. The instrumental value of a task can be increased by linking the task to goals that already have instrumental value for students. In this way we can increase the intrinsic value of the task. But is it enough? Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Sheldon et al. (2004) found that increasing the intrinsic value of a task (for instance by telling students that what they learn will eventually enable them to cure sick children) did increase their intrinsic motivation and thus deep level learning. Extrinsic goals did not have this positive effect.

SDT explicitly states that extrinsic goals or extrinsic motivational information might decrease intrinsic motivation and they may also decrease their well-being. Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Soenens et al. (2004) compared instrumental motiva-tional information in an experiment with three other conditions, namely information aimed at an intrinsic goal, information aimed at an extrinsic goal and a combination of both types of information. The group who received the intrinsic-only information

had the highest scores (both on performance and intrinsic motivation). The extrinsic group had the lowest scores. A combination of extrinsic and intrinsic goals leads to less superior results than the intrinsic-only condition.

These researchers explained that extrinsic goals might be perceived by the students as “controlling” and may thus “counterbalance” the positive effects of intrinsic goals. Husman et al. (2004) put it like this: “Do future goals affect intrinsic motivation in the same negative way that extrinsic reasons for studying have been reported to affect intrinsic motivation?” (66). This account finds support in the find-ing reported by Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Soenens et al. (2004). They reported an interaction effect between (non)controlling contexts and intrinsic/extrinsic goals. Students seem to benefit significantly more from intrinsic goals in an autonomy supportive context than in a controlling context. Unfortunately, experiments such as these are still rare.

In our research programme recently some studies were conducted to increase our understanding of the effects of motivational information. In the first study, it was assessed how intrinsic motivation can be enhanced by presenting instrumental infor-mation to students. This was done by providing 150 Dutch first-year university students with a mind-set at the start of a course and asking them to reflect on what they had been learning during the course, at regular intervals. The results showed that students who got long-term instrumental (career) information and short-term instru-mental (study) information are outperformed by students who got non-instruinstru-mental information that only focuses on aspects of joy and relatedness. Latent semantics anal-ysis showed that the condition with non-instrumental information which led to the best study results was associated with students’ self-written reflection reports that had a relative high status of words associated with intrinsic motivation.

Another study at our department showed that the effects of presenting motivational information to students are not always as straight forward as some have suggested. Van Nuland, Martens, and Boekaerts (2008) found that presenting extrinsic goals to students between 12 and 16 years of age had no effects for female students and an inversed effect for male students: extrinsic goals increased intrinsic motivation. The provisional results of this study show that presenting such motivational information is not easy. What teachers or researchers believe to be intrinsic or motivating may be interpreted differently by students. This makes it difficult to induce the right “mind-set” to students.

Assessment as extrinsic incentive

In line with this interesting line of research, in the present study we take a closer look at the role of assessment.

Amongst the many options that are possible to stimulate an autonomy supportive learning situation, using praise as informational feedback is often mentioned (e.g. Tsai et al. 2008). In other words, the way feedback is set up, can be very important to the way students experience the learning climate. Although feedback is considered to be a crucial aspect of education, it is certainly not without risk. Ryan and Deci (2008, p. 117) put it:

Gathering information and providing feedback about performance in educational settings is extremely important for maintaining student and teacher motivation and for informing educational policy. Nonetheless, a disturbing trend in information gathering

currently exists in the American educational system. Referred to as high-stakes testing and advocated as a means of motivating students and prompting improved average performance in schools, this trend will predictably lead to a variety of negative consequences in terms of the quality of students’ learning and their psychological well-being.

Ryan and Deci state that testing can basically have three functional significances: informational, controlling and “amotivating”. Evaluations and assessments have informational significance when they provide relevant feedback in a relatively supportive way. That is, when an assessment provides individuals with specific feed-back that points the way to being more effective in meeting challenges or becoming more competent, and does so without pressuring or controlling the individuals, it tends to have a positive effect on self-motivation.

Evaluations and assessments have controlling significance, in contrast, when they are experienced by the individuals as pressure towards specified outcomes or when they represent a means by which the evaluators attempt to control the activity and effort of the individuals or units being tested. According to SDT, when evaluations have controlling significance they tend to produce compliance and rote memorisation, but they ultimately undermine self-motivation, investment and commitment in the domain of activity being evaluated.

Finally, evaluations and assessments have an “amotivating significance” when they convey incompetence to the individuals. Evaluations which have standards that are not optimally challenging or that are perceived to be beyond the reach of the indi-viduals being tested are experienced as amotivating: they undermine all motivation and lead to withdrawal of effort. Empirical evidence for some negative effects of the high-stakes was provided by Cizek (2001).

In education, assessment is one of the most crucial feedback mechanisms. Students take a test, exam, or perform on a task and get feedback. Rakoczy et al. (2008) conceptualise feedback as “information provided by an agent [in our case by the teacher] regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding” (117). This feedback can be a comment, a grade and so on. It can be summative (grading) or formative (a focus on informing students about progress). Feedback can give students tips and hints or it can be more negative, in that it focuses on what students did not know or on the mistakes they made. Unfortunately the latter is the most common use of assessment. It is clear that assessment contains a lot of motivational or instrumental information. So, what is known about the motivational effects of assessment and feedback?

Positive versus negative feedback

An important distinction in feedback after an assessment is the distinction between “positive” and “negative”. Koka and Hein (2005) reported a positive effect on intrinsic motivation when teacher feedback was perceived as positive. These researchers did not experimentally manipulate with feedback. In fact, not much experimental variation of feedback type is available. Some examples of experimen-tal manipulation of feedback in an attempt to increase intrinsic motivation come from Dineen and Niu (2008, p. 45): “Where possible, work is assessed using descriptive evaluations (i.e. excellent, very good, good, adequate, poor) and diag-nostic comments. The intention is to lessen an obsession with grades and ranking, and encourage student reflection” (H5). The main purpose of the Dineen and Niu)

study was to test the efficacy of a western creative pedagogic model in a Chinese context. The study took the form of a teaching intervention through which we aimed to create a temporary “micro” environment, which would positively affect student creativity and related psychological attributes such as intrinsic motivation and confidence. To create such an environment, several factors were simulta-neously addressed. These included classroom settings, scheduling, teaching styles and approaches, teaching methods, tasks and projects, as well as assessments and feedback strategies. Dineen and Niu) found that when compared to the traditional Chinese pedagogical model, the creative pedagogic model developed in the UK significantly improved Chinese students’ creativity and also their perceptions of their own originality, quality of work, confidence in experimentation, work-rate, motivation and enjoyment.

Positive performance feedback has generally been found to enhance intrinsic motivation (Vansteenkiste and Deci 2003). Rakoczy et al. (2008) state that the distinction between informational and controlling functional significance of feed-back is crucial. In the context of cognitive evaluation theory (CET), which is part of self-determination theory this distinction is crucial. Social contexts have control-ling significance when they are experienced as pressuring individuals towards spec-ified outcomes, thus shifting the perceived locus of causality from internal to external. In contrast, social environments have informational significance when they are experienced as supporting competent involvement. The salience of information and control in the particular situation is decisive for the experience of competence and autonomy, which may, in turn, lead to self-determined behaviour (Ryan and Deci 2000). The distinction between informational and controlling components of the social context can also be used to understand the effects of feedback. In some cases, positive feedback (for instance praise) may have negative motivational and cognitive consequences: positive feedback fosters motivation and achievement only when it is effectance-relevant and provided in a supportive way (i.e. when it shows students how they can be more effective in meeting challenges or gaining competence, without being pressuring or controlling) (Rakoczy et al. 2008). So, even positively formulated feedback, if experienced as pressuring and controlling, implies negative motivational and cognitive consequences. A study by Rakoczy et al. (2008) showed that positive evaluative feedback in the classroom was associ-ated with increased intrinsic motivation, whereas negative evaluative feedback was not related to motivation. Informational feedback was shown to foster motivation via emotional experience and cognitive processing. This is in line with findings of Corpus, Ogle, and Love-Geiger (2006), showing positive effects of praise and posi-tive feedback when compared to the social comparison feedback. The interplay with student characteristics is confirmed by Katz et al. (2006) who showed that amongst children with moderate interest, absence of positive feedback was associated with decreased intrinsic motivation for boys, and increased motivation for girls. This gender-related pattern was interpreted by these researchers as suggesting that girls with moderate interest perceived the positive feedback as an attempt to control them.

Finally, we can conclude that although many of these studies were conducted in traditional “classroom” contexts, similar effects are also reported in learning situation that imply more student’s self-regulation, and even in computer-based education where the computer provides the feedback (Bracken, Jeffres, and Neuendorf 2004; Bracken and Lombard 2004).

Research questions

There are important indications that the way students perceive a learning climate (e.g. controlling or stimulating) is significantly influenced by feedback and assessment. The tendency towards high-stakes testing is not without danger, when considered from a motivational perspective. However, at present much is unclear about the rela-tion between feedback and motivarela-tional state, as it is with the effects of motivarela-tional information in general. More specifically, the interplay with student characteristics such as initial motivational patterns is mostly unclear. In addition to this, in the “new” learning environments, with an emphasis on self-directed learning we see a strong increase of group work, peer assessment, computer-supported collaboration and so on. This means that feedback after assessments is often at a group level. This might complicate the complex relation between student characteristics, group processes and feedback type even further. The central research question then is what are the effects of positive, neutral or negative feedback presented to collaborating teams of students, on students’ intrinsic motivation and on group processes?

Method Participants

The participants were 138 first-year students from the Department of Education of Leiden University (17 males, 121 females; aged between 17 and 33 years, M = 18.9, SD = 1.30). Due to external circumstances some students were not able to fill in all the questionnaires at all data collection points across the three months of the experi-ment. Moreover, some students dropped out from the study programme. This loss of data was unsystematic and was comparable across conditions.

The experiment was part of a regular, introductory course in education. It was part of the study requirements for all students enrolled in the course. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three experimental conditions in a within-subjects design. Due to logistic considerations, the number of participants across the conditions was not equal.

Procedure

The experiment took place in a four-month period. During the course students had to attend classes, work by themselves, as well as in small groups on tasks and assign-ments. The learning environment was aimed at “blended” learning, combining various aspects of “new learning”. In the course, students developed competencies related to lectures, group work and self-study. A lot of cooperative learning was required as well as self-regulation during self-study that prepared the group meetings. Students made use of the electronic learning environment of Leiden University, which is a black-board-based environment in which students can find individualised assignments, group work tools and so on. During the course three types of feedback, positive, neutral and negative, were used as a within-subject factor. Thus, during the course as a whole every subject received more or less equal amounts of positive, neutral and negative feedback. The participants received 19 times feedback based on a group product. In the condition with positive feedback, we used positively formulated suggestions for improvement (e.g. “you can improve your product by B”) and the feedback always started with emphasising the positive points of the product. More

words were used for the positive comments without really changing the content. In the neutral condition, students got exactly the same feedback, but in a random order and formulated in a neutral way (e.g. “with regard to B it can be noticed that…”). In the negative condition, students again got exactly the same feedback but formulated in a negative way (e.g. “your product was insufficient with regard to B”). In the negative condition, the feedback started with the negative comments. It is important to note that concerning the factual content of the feedback comments there was no difference between the conditions and that all participants got all conditions during the course period. Questionnaires were administered each time a few hours after the feedback was handed out.

Variables

Measurements were collected by means of internet questionnaires that were adminis-tered after each of 19 classes in the course. The questionnaire on interest and on basic needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness contained eight bipolar items, two items for each construct. A listing of these items is appended (Appendix 1). Responses were collected on a five-point scale. The reliability of the scales per class according to Cronbach’s α ranged for autonomy from α =.81 to α = .96 with median α = .91,

for competence from α = .74 to α = .92 with median α = .85, for relatedness from α =

.65 to α = .85 with median α = .76, and for interest from α = .69 to α = .92 with

median α = .82.

The questionnaire on positive and negative emotions contained a list of 11 state-ments about emotions during the class like “I felt tense”, “I felt in good spirits”, “I felt relaxed” and “I felt frustrated”. The student could indicate his of her level of agree-ment on a five-point scale. After reversing scoring directions for negative emotions, the reliability per session using Cronbach’s α ranged from α = .882 to α = .954 with

median α = .921.

At four moments during the course, students delivered an individual paper and received a grade for its quality. These grades could theoretically range from 0 to 10, with 10 being the perfect score.

Analysis

First, we explored the data by investigating the overall average scores in the three conditions. After these explorations we conducted our main analyses with a restricted set of variables: autonomy, competence, relatedness and interest. Because of the hier-archical nature of our data on autonomy, competence, relatedness and interest we used multi-level analysis. Each aspect was measured in each of maximally 19 sessions. Sessions were nested within students, students were nested within cooperative groups. The number of groups was 29. Each group contained typically four or five students. There was one group with six students. As a result all the analysis models contained three levels: the group level, the student level and the session level.

Each session was characterised by the type of feedback that the students received. Type of feedback was coded with two dummy variables, fbpos and fbneg. Fbpos was 1 when the student received positively phrased feedback in the current session and 0 otherwise. Fbneg was coded 1 when the student received negatively phrased feedback in the current session and 0 otherwise. Both variables were coded 0, when the student received feedback that was neutrally formulated. That way, neutral feedback became

the reference category in the regression analysis. In preliminary analyses, the option to code feedback as a dimension form negative (–1) through neutral (0) to positive (+1) was rejected, because it consistently explained less variance. Type of feedback was systematically varied over sessions and groups.

First, we analysed the data on autonomy, competence and relatedness separately to establish the effect of positive and negative feedback and the variability of these effects between groups and between students. For each analysis two models were constructed. The unconditional model contains the intercept and three components of variance: between groups, between students and between sessions. Fixed and random effects were consecutively added and tested. The end model described the effect of positive and negative feedback, overall (fixed) and the variability of their effect (random) at the group level and the student level. Of the random effects only signifi-cant effects are reported. Fixed effects were tested using the Wald test, random effects using the likelihood-ratio test.

Next, we analysed the data on interest, also to establish the effects of positive and negative feedback and the variability of these effects at different levels of analy-sis. In addition, we explored sequentially the effects of autonomy, competence and relatedness on interest and on the relation of positive and negative feedback with interest.

Results

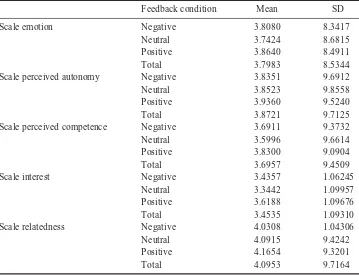

Table 1 shows the scores per condition. In all conditions, the positive feedback condi-tions seem to outperform the neutral and the negative feedback condicondi-tions.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of all scales.

Feedback condition Mean SD

Scale emotion Negative 3.8080 8.3417 Neutral 3.7424 8.6815 Positive 3.8640 8.4911

Total 3.7983 8.5344

Scale perceived autonomy Negative 3.8351 9.6912 Neutral 3.8523 9.8558 Positive 3.9360 9.5240

Total 3.8721 9.7125

Scale perceived competence Negative 3.6911 9.3732 Neutral 3.5996 9.6614 Positive 3.8300 9.0904

Total 3.6957 9.4509

Scale interest Negative 3.4357 1.06245 Neutral 3.3442 1.09957 Positive 3.6188 1.09676

Total 3.4535 1.09310

Scale relatedness Negative 4.0308 1.04306 Neutral 4.0915 9.4242 Positive 4.1654 9.3201

Total 4.0953 9.7164

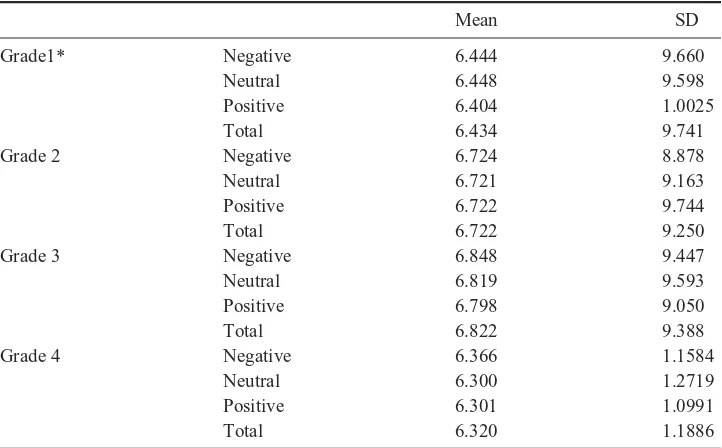

Table 2 depicts the grades in the conditions. These grades do not differ signifi-cantly across the conditions.

Although the data in Table 1 seem to indicate effects in the expected conditions, these averages do not take into account that the data are nested, in individuals, groups and sessions. Multi-level analysis enables us to look more into detail in this nested structure and to correct for effects form for instance from the group partici-pants who were joining.

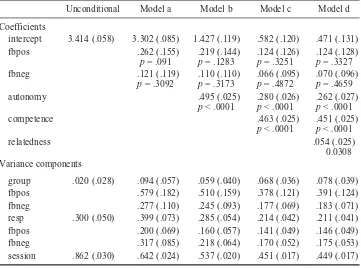

Table 3 summarises the results of the multi-level analyses of autonomy, compe-tence and relatedness using the unconditional model and the end model. The tests that were used consecutively in the process of the construction of the end model are reported in the text. Unstandardised regression weights are labelled as b. The analysis of autonomy showed initially that positive feedback (fbpos) in general had a positive effect on autonomy (b = .072, SE = .036, p = .0455). However, the fixed effect of negative feedback (fbneg) proved to be not significant (b = .004, SE = .04, p = .992) and rendered the fixed effect of fbpos not significant as well. Adding random effects of fbpos and fbneg for students significantly diminished the log likelihood-ratios (χ2(2) = 19.091, p < .0001, respectively χ2(3) = 31.29, p < .0001). Random effects of

fbpos and fbneg for groups did not improve the log likelihood-ratio (χ2(2) = 1.013,

p = .6026, respectively χ2(3) = 6.381, p = .0945). Thus, according to the final model

positive and negative feedback had no overall (fixed) effect on autonomy, but students varied systematically in how they react to positive (σ2 = .115) and negative

(σ2 = .184) feedback.

Adding fbpos to the model indicates that positive feedback enhances sense of competence (b = .191, SE = .04, p < .0001). Adding fbneg also appears to contribute to sense of competence (b = .096, SE = .044, p = .0291).

Furthermore, adding random effects for fbpos and fbneg improved the prediction of competence considerably (χ2(2) = 16.844, p = .0002, respectively χ2(3) = 49.057,

Table 2. Grades at four points in the course in different feedback conditions.

Mean SD

Grade1* Negative 6.444 9.660

Neutral 6.448 9.598

Positive 6.404 1.0025

Total 6.434 9.741

Grade 2 Negative 6.724 8.878

Neutral 6.721 9.163

Positive 6.722 9.744

Total 6.722 9.250

Grade 3 Negative 6.848 9.447

Neutral 6.819 9.593

Positive 6.798 9.050

Total 6.822 9.388

Grade 4 Negative 6.366 1.1584

Neutral 6.300 1.2719

Positive 6.301 1.0991

Total 6.320 1.1886

*Grades can vary theoretically between 0 and 10.

Educational Studies

321

Table 3. Multi-level regression analyses of positive and negative feedback on autonomy, competence and relatedness.

Autonomy Competence Relatedness

unconditional end model unconditional end model unconditional end model

Coefficients

intercept 3.809 (.061) 3.779 (.067) 3.677 (.050) 3.578 (.062) 4.070 (.081) 4.074 (.089)

fbpos .084 (.049)

p = .0865

.247 (.075)

p = .001

.056 (.060)

p = .3506

fbneg .017 (.054)

p = .7529

.100 (.063)

p = .1124

−.044 (.064)

p = .4849

Variance components

group .00 (.00) .00 (.00) .00 (.00) .00 (.00) .115 (.051) .141 (.061)

fbpos .094 (.038) .055 (.027)

fbneg .045 (.032)

resp .472 (.062) .533 (.075) .288 (.041) .410 (.062) .306 (.048) .314 (.051)

fbpos .115 (.038) .088 (.042)

fbneg .184 (.047) .291 (.064) .107 (.040)

p < .0001). However, the overall (fixed) effect of fbneg disappeared as a result of this addition. Adding a random effect for groups of fbpos improved prediction (χ2(2) =

16.89, p = .0002), but not of fbneg (χ2(2) = 6.296, p = .0981). According to the final

model positive feedback in general strengthens feelings of competence (b = .247), but there are also systematic differences between groups (σ2 = .094) and between students

(σ2 = .088) in how they react to positive feedback. The general effect of negative

feed-back on feelings of competence is not significant, but there are systematic differences between students (σ2 = .291) in how they react to negative feedback.Overall effects

of fbpos and fbneg on relatedness are clearly absent (b = .037, SE = .038, p = .3302, respectively b = –.042, SE = .042, p = .3173). However, random effects of fbpos and fbneg for students are both significant (χ2(2) = 12.981, p = .0015, respectively χ2(3)

= 26.862, p < .0001). The random effects for groups are also significant (χ2(2) =

10.092, p = .0064, respectively χ2(3) = 9.088, p < .0281). However, allowing random

effect of fbpos for groups, reduced the variance associated with the random effect of fbpos for students virtually to zero ((χ2(3) = 2.742, p = .4331).The final model then

implies that in general relatedness is not affected by positive and negative feedback, but that groups differ systematically in how they react to positive (σ2 = .055) and

negative (σ2 = .045) feedback and that students differ systematically in how they react

to negative feedback (σ2 = .107).

The analysis of interest initially proceeds along the same course (Table 4). Sequentially adding fixed effects of positive and negative feedback leads initially to significant results (b = .237, SE = .048, p < .0001, respectively b = .112, SE = .053,

p = .0346). Random effects of fbpos and fbneg for students proofed to be significant (χ2(2) = 80.409, p < .0001, respectively χ2(3) = 92.089, p < .0001). Also random

Table 4. Parameter estimates using positive feedback, negative feedback, autonomy, competence and relatedness as predictors of interest.

Unconditional Model a Model b Model c Model d

Coefficients

intercept 3.414 (.058) 3.302 (.085) 1.427 (.119) .582 (.120) .471 (.131) fbpos .262 (.155)

group .020 (.028) .094 (.057) .059 (.040) .068 (.036) .078 (.039) fbpos .579 (.182) .510 (.159) .378 (.121) .391 (.124) fbneg .277 (.110) .245 (.093) .177 (.069) .183 (.071) resp .300 (.050) .399 (.073) .285 (.054) .214 (.042) .211 (.041) fbpos .200 (.069) .160 (.057) .141 (.049) .146 (.049) fbneg .317 (.085) .218 (.064) .170 (.052) .175 (.053) session .862 (.030) .642 (.024) .537 (.020) .451 (.017) .449 (.017)

effects for groups of fbpos and fbneg improved prediction (χ2(2) = 45.048, p < .0001,

respectively χ2(3) = 18.043, p = .0004). By adding the random effect of fbneg for

students, however, the fixed effect of fbneg lost its significance and by adding the random effect of fbpos for groups, the fixed effect of fbpos also lost its significance. According to Model a, then, there were no general effects of positive and negative feedback, but there were substantial differences both between groups (σ2 = .579,

respectively σ2 = .277) and between individual students (σ2 = .200, respectively σ2 =

.317) in how they reacted to positive and negative feedback.

Introducing the basic need variables: autonomy, competence and relatedness in the analysis model allowed us to analyse how basic need fulfilment related to interest directly and to explore to what extent basic need fulfilment moderated the influence of the two types of feedback as indicated by the reduction of variability of their effects at the group level and the student level. Addition of basic need fulfilment variables to the model one by one disclosed which of these variances were affected.

According to Model d, both feelings of autonomy and of competence had a strong positive overall effect on reports of interest (b = .262, SE = .027, p < .0001, respec-tively b = .451, SE = .025, p < .0001). They reduced the interest variance between sessions substantially (σ2 = .642 > .537 > .451). They also explained considerable

parts of the interest variance between students (σ2 = .399 > .285 > .214). Feelings of

autonomy in addition appeared to explain small parts of the variance of interest effected by positive and negative feedback both at the level of groups and at the level of students: apparently, more autonomous students (σ2 = .200 > .160, respectively σ2 = .317 > .218) and students in more autonomous groups (σ2 = .579 > .510,

respec-tively σ2 = .277 > .245) gained more interest from positive, respectively negative

feedback than their counterparts. The relative interest gain of autonomous students from negative feedback is noteworthy here. Feelings of competence also facilitated the effects of positive and negative feedback, but especially the effect of positive feed-back at the group level (σ2 = .510 > .378 for positive feedback and σ2 = .245 > .177

for negative feedback), which suggested that positive feedback boosted interest espe-cially in groups of students with high sense of competence. In addition, individual students feeling competent gained slightly in interest both from positive and negative feedback (σ2 = .160 > .141, respectively σ2 = .218 >.170). Relatedness had a small

direct effect (b = .054, SE = .025, p = .0308) on interest but appeared not to explain the influence of different types of feedback.

Discussion

In education, research has shown that students’ (intrinsic) motivation is low (e.g. Boekaerts and Martens 2006; Legault, Green-Demers, and Pelletier 2006; Manalo et al. 2006; Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Soenens et al. 2004).

In line with previous studies, this study shows again that inducing mind-sets by giving specific motivational information is not as straightforward as some have claimed, or as many teachers think it is. In this study, we used feedback on assess-ments of group admissions to manipulate with motivational information. Earlier stud-ies on the effects of positive versus more negative assessment have produced mixed results (e.g. Bracken, Jeffres, and Neuendorf 2004; Bracken and Lombard 2004; Katz et al. 2006). In this study, during a course three within-subject conditions were used. The learning processes in this course can be characterised as self-regulative. There was a strong emphasis on collaboration and on the use of ICT (via blackboard).

In a period of about three months, the participants got feedback based on a group product. In the condition with positive feedback, we used positively formulated suggestions for improvement, in the neutral condition students got exactly the same feedback, but in a neutral way, and in the negative condition the factually identical feedback was presented in a more negative way.

We compared the grades the participants got on various moments in time. These did not differ significantly across conditions. With multi-level analysis we made a more detailed distinction of the influence of the group participants belonged to and the session number. We also analysed models in which positive feedback, negative feed-back, autonomy, competence and relatedness were as predictors of interest. Although relatively explorative, some interesting findings can be reported. In line with SDT, feel-ings of autonomy and of competence have a significant positive effect on report of inter-est. They reduce the interest variance between sessions substantially. Feelings of autonomy in addition appear to explain small parts of the variance of interest effected by positive and negative feedback both at the level of groups and at the level of students: apparently, more autonomous students and students in more autonomous groups gain more interest than their counterparts from positive respectively negative feedback. The relative interest gain of autonomous students from negative feedback is striking. Feel-ings of competence also facilitate the effects of positive and negative feedback, but especially the effect of positive feedback at the group level, which suggests that positive feedback boosts interest especially in groups of highly competent students.

This study certainly has some shortcomings, amongst which are the relatively small sample size for multi-level analyses, the relatively high percentage of female participants and the fact that we tried to get a grip of very complex motivational processes by means of quantitative techniques. A good supplement or recommenda-tion for future research would be to use qualitative research methods to understand the complex process that takes place when groups of self-regulating students are confronted with feedback.

Note

This article is partly based on a paper presented at the 11th international conference on motivation, 22 August 2008.

Notes on contributors

Rob Martens works at the Open University of the Netherlands at the Ruud Moor Centre as a full professor on educational innovation and teacher education.

Cees de Brabander works at Leiden University, Educational Studies on subjects such as educa-tional innovation and student motivation.

Jeroen Rozendaal worked at Leiden University at the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, the Department of Education and Child studies, with a focus on the research of moti-vational processes. Currently, he is the owner of StudioRev in the Netherlands, which is about the producing and directing of cultural and educational media.

Monique Boekaerts works at Leiden University, Educational Studies. She is a full professor with a focus on motivation and self-regulated learning.

Rien van der Leeden works at Leiden University at the Department of Psychology and is a specialist in research methodology.

References

Bjorklund, D.F., and A.D. Pellegrini. 2002. The origins of human nature. Evolutionary developmental psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Boekaerts, M., and R. Martens. 2006. Motivated learning: What is it and how can it be

enhanced? In Instructional psychology: Past, present and future trends. A look back and a look forward, ed. L. Verschaffel, F. Dochy, M. Boekaerts, and S. Vosniadou, 113–30. London: Elsevier.

Bracken, C.C., L.W. Jeffres, and K.A. Neuendorf. 2004. Criticism or praise? The impact of verbal versus text-only computer feedback on social presence, intrinsic motivation, and recall. Cyber Psychology and Behavior 7: 349–57.

Bracken, C.C., and M. Lombard. 2004. Social presence and children: Praise, intrinsic motiva-tion, and learning with computers. Journal of Communication 54: 22–37.

Cizek, G.J. 2001. More unintended consequences of high-stakes testing. Educational Measurement, Issues and Practice 20: 19–28.

Corpus, J.H., C.M. Ogle, and K.E. Love-Geiger. 2006. The effects of social-comparison versus mastery praise on children’s intrinsic motivation. Motivation and Emotion 30: 335–45. Dineen, R., and W. Niu. 2008. The effectiveness of western creative teaching methods in

China: An action research project. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 2: 42–52.

Garris, R., R. Ahlers, and J.E. Driskell. 2002. Games, motivation, and learning: A research and practice model. Simulation and Gaming 33: 441–67.

Grouzet, F.M.E., T. Kasser, A. Ahuvia, J.M.F. Dols, Y. Kim, S. Lau, R.M. Ryan, S. Saunders, P. Schmuck, and K.M. Sheldon. 2005. The Structure of goal contents across 15 cultures.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89: 800–16.

Groves, M. 2005. Problem-based learning and learning approach: Is there a relationship?

Advances in Health Sciences Education 10: 315–26.

Hardre, P., and J. Reeve. 2003. A motivational model of rural students’ intentions to persist in, versus drop out of high school. Journal of Educational Psychology 95: 347–56. Hidi, S., and K.A. Renninger. 2006. The four-phase model of interest development.

Educational Psychologist 41: 111–27.

Husman, J., W. Derryberry, H. Crowson, and R. Lomax. 2004. Instrumentality, task value and intrinsic motivation: Making sense of their interdependence. Contemporary Educational Psychology 29: 63–76.

Järvelä, S., and S. Volet. 2004. Motivation in real-life, dynamic, and interactive learning envi-ronments: Stretching constructs and methodologies. European Psychologist 9: 193–7. Katz, I., A. Assor, Y. Kanat-Maymon, and Y. Bereby-Meyer. 2006. Interest as a motivational

resource: Feedback and gender matter, but interest makes the difference. Social Psychology of Education 9: 27–42.

Koka, A., and V. Hein. 2005. The effect of perceived teacher feedback on intrinsic motivation in physical education. International Journal of Sport Psychology 36: 91–106.

Legault, L., I. Green-Demers, and L. Pelletier. 2006. Why do high school students lack moti-vation in the classroom? Toward an understanding of academic motimoti-vation and the role of social support. Journal of Educational Psychology 98: 567–82.

Levesque, Ch., A.N. Zuehlke, L.R. Stanek, and R.M. Ryan. 2004. Autonomy and competence in German and American university students: A comparative study based on self-determi-nation theory. Journal of Educational Psychology 96: 68–85.

Manalo, E., M. Koyasu, K. Hashimoto, and T. Miyauchi. 2006. Factors that impact on the academic motivation of Japanese university students in Japan and in New Zealand.

Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient 49: 114–31.

Martens, R., Th. Bastiaens, and P.A. Kirschner. 2007. New learning design in distance educa-tion: Its impact on student perception and motivation. Distance Education 28: 81–95. Martens, R., J. Gulikers, and Th. Bastiaens. 2004. The impact of intrinsic motivation on

e-learning in authentic computer tasks. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 20: 368–76. Pintrich, P.A. 2003. A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in

learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology 95: 667–87.

Rakoczy, K., E. Klieme, A. Bürgermeister, and B. Harks. 2008. The interplay between student evaluation and instruction: Grading and feedback in mathematics classrooms. Journal of Psychology 216: 111–24.

Reeve, J., G. Nix, and D. Hamm. 2003. Testing models of the experience of self-determina-tion in intrinsic motivaself-determina-tion and the conundrum of choice. Journal of Educational Psychol-ogy 95: 375–92.

Ryan, R.M., and E.L. Deci. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well being. American Psychologist 55: 68–78. Ryan, R.M., and E.L. Deci. 2008. The high-stakes testing controversy. “Higher Standards”

can prompt poorer education. http://www.psych.rochester.edu/SDT/index.php (accessed October 15, 2009).

Saab, N., W. van Joolingen, and B. van Hout-Wolters. 2009. The relation of learners’ motiva-tion with the process of collaborative scientific discovery learning. Educational Studies

35: 205–22.

Simon, H.A. 1995. The information-processing theory of mind. American Psychologist 50: 507–8.

Simons, R., J. Van der Linden, and T. Duffy. 2000. New learning. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Stoof, A., R. Martens, J. Van Merriënboer, and Th. Bastiaens. 2002. The boundary approach of competence: A constructivist aid for understanding and using the concept of compe-tence. Human Resource Development Review 1: 345–65.

Strijbos, J.W., P.A. Kirschner, and R.L. Martens, eds. 2004. What we know about CSCL: And implementing it in higher education. Boston: Kluwer Academic/Springer Verlag.

Tsai, Y., M. Kunter, O. Lüdtke, U. Trautwein, and R.M. Ryan. 2008. What makes lessons interesting? The role of situational and individual factors in three school subjects. Journal of Educational Psychology 100: 460–72.

Van Nuland, H., R. Martens, and M. Boekaerts. 2008. The effect of motivational why-infor-mation on intrinsic motivation, performance and self-regulated learning behaviour in a classroom context. Paper presented at ICM 2008 Motivation in Action, 11th International Conference on Motivation, August 22, in Turku, Finland.

Vansteenkiste, M., and E.L. Deci. 2003. Competitively contingent rewards and intrinsic moti-vation: Can losers remain motivated? Motivation and Emotion 27: 273–99.

Vansteenkiste, M., J. Simons, W. Lens, K. Sheldon, and E. Deci. 2004. Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: The synergistic effects of intrinsic goal contents and auton-omy-supportive contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 87: 246–60. Vansteenkiste, M., J. Simons, W. Lens, B. Soenens, L. Matos, and M. Lacante. 2004. Less is

sometimes more: Goal-content matters. Journal of Educational Psychology 96: 755–64.

Appendix 1. Listing of items in motivation questionnaires

Interest:

At this moment I would prefer to work on another task

At this moment I am very interested in this task

I find my work in doing this task boring I find my work in doing this task fascinating Autonomy:

In doing this task we are allowed NOT enough room to take our own decisions

In doing this task we are allowed enough room to take our own decisions

In doing this task I find we have NOT enough freedom

In doing this task I find we have enough freedom

Competence:

I do NOT feel capable to perform this task satisfactory

I feel capable to perform this task satisfactory

I do NOT have enough knowledge and skills for this task

I have enough knowledge and skills for this task

Relatedness:

In this task we do NOT work well together Doing this task we work in harmony I would rather like to work in another

group

I like working in this group