IN SMALL ISLANDS: A SOCIAL CAPITAL ANALYSIS

BUDIATI PRASETIAMARTATI

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY

B O G O R

STATEMENT ABOUT DISSERTATION AND

INFORMATION SOURCE

I herewith declare that the dissertation titled “Community-Based Coral Reef Management in Small Islands: A Social Capital Analysis” is made by myself, under the supervison of the Supervisory Committee and has not yet been proposed in any form to other university. The sources that derived or cited from published and unpublished journal articles or books of other authors have been acknowledged and the list of references is listed at the end of the dissertation.

Bogor, April 2007

ABSTRACT

BUDIATI PRASETIAMARTATI. Community-Based Coral Reef Management in Small Islands: A Social Capital Analysis. Under the supervision of AKHMAD FAUZI, ROKHMIN DAHURI, ACHMAD FAHRUDIN, and HELLMUTH LANGE.

Human activities including bomb and poison fishing and coral mining have threatened Indonesian coral reefs. Many programs have been promoted to alleviate the problem. The focus of social capital’s contribution to sustainable coral reef resource use has been given little attention. Social capital that defined as trust, norms of reciprocity, and networks is argued to facilitate the formation of collective action and institution, which may contribute to sustainable coral reef resource use.

The study is carried out in five islands in South Sulawesi and analyses the state of coral reef, destructive fishing, and fishery sustainability. Three dimensions of social capital (i.e. bonding, bridging and linking social capital) are assessed, including the impact of social capital investment. It discusses institutional analysis of community-based institutional arrangements. Further, a simulation experiment of an agent-based modelling is made to understand dynamic impact of social capital on destructive fishing and fishery.

Results show that bonding, bridging and linking social capital affect the formulation and enforcement of rules and institution at local level. Social capital investment – through networks, capacity and institution building – is a necessary condition for coral reef management, but not sufficient. Enforcing local rules requires credible commitment, but is difficult to attain because of the problem of fit between rules and resource system. When the community capacity and institution are weak, destructive fishing are proliferated, because social norms are not sufficiently strong to prevent widespread individual opportunism.

The study recommends three aspects to achieve sustainable coral reef management: (1) to promote multi-scale governance that can link up different levels of management organization; (2) to improve fishers’ welfare through fulfillment of basic needs, to avert the use of destructive fishing tools for economic reason; (3) to increase disparities of fish price and production costs between fishing using destructive gears and those that do not.

ABSTRAK

BUDIATI PRASETIAMARTATI. Pengelolaan Terumbu Karang Berbasis Masyarakat di Pulau-Pulau Kecil: Analisis Modal Sosial. Dibimbing oleh AKHMAD FAUZI, ROKHMIN DAHURI, ACHMAD FAHRUDIN, dan HELLMUTH LANGE.

Kegiatan manusia, termasuk penangkapan ikan dengan bom dan bius dan penambangan karang, mengancam terumbu karang Indonesia. Banyak progam ditujukan untuk mengatasi permasalahan ini. Namun demikian, kontribusi modal sosial dalam pemanfaatan terumbu karang yang berkelanjutan belum mendapat perhatian. Modal sosial didefinisikan sebagai rasa percaya, norma resiprokal, dan jaringan yang memfasilitasi terbentuknya aksi bersama dan institusi, yang dapat berkontribusi pada pengelolaan sumberdaya termasuk terumbu karang.

Disertasi ini dilakukan di lima pulau kecil di Sulawesi Selatan dan mengkaji kondisi terumbu karang, penangkapan ikan yang merusak, dan keberlanjutan perikanan. Kemudian dianalisis tiga dimensi modal sosial (bonding, bridging, linking) dan dampak investasi modal sosial, serta kelembagaan pengelolaan terumbu karang berbasis masyarakat. Selanjutnya dilakukan simulasi menggunakan agent-based modelling untuk memahami dinamika dampak modal sosial terhadap penangkapan yang merusak dan perikanan.

Hasil analisis menunjukkan bahwa jaringan modal sosial bonding, bridging dan linking mempengaruhi pembentukan dan pelaksanaan aturan dan institusi di tingkat lokal. Investasi modal sosial – melalui peningkatan jaringan, kemampuan dan kelembagaan – merupakan kondisi perlu bagi pengelolaan terumbu karang, namun belum cukup. Komitmen penegakan aturan lokal sulit diterapkan karena perbedaan skala antara aturan dan sistem sumberdaya. Ketika kemampuan dan kelembagaan komunitas lemah, penangkapan ikan yang merusak meningkat, karena norma sosial tidak cukup kuat untuk menghindari tindakan oportunistik yang meluas.

Studi merekomendasikan tiga hal: (1) mendorong tata pengelolaan multi-skala yang mengaitkan organisasi manajemen di berbagai tingkatan; (2) meningkatkan kesejahteraan nelayan untuk menghindari alasan penggunaan bom atau bius karena masalah ekonomi; (3) memperlebar perbedaan harga ikan dan biaya produksi antara penangkapan dengan bom/bius dan yang bukan.

© Bogor Agricultural University’s All right, 2007 All right reserved

No part or all of this dissertation may be reproduced or duplicated in any form including photocopy, printing microfilm, etc. without a written

COMMUNITY-BASED CORAL REEF MANAGEMENT

IN SMALL ISLANDS: A SOCIAL CAPITAL ANALYSIS

BUDIATI PRASETIAMARTATI

Dissertation

Partial Fulfillment for Obtaining a Doctoral Degree in Marine and Coastal Resources Management

GRADUATE SCHOOL

BOGOR AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY

B O G O R

Dissertation’s title : Community-Based Coral Reef Management in Small Islands: A Social Capital Analysis

Name : Budiati Prasetiamartati

Student ID : C 261040202

Approved by the Supervisory Committee,

Dr. Ir. Akhmad Fauzi, M.Sc. Head

Prof. Dr. Ir. Rokhmin Dahuri, MS. Member

Dr. Ir. Achmad Fahrudin, MS. Member

Prof. Dr. Hellmuth Lange Member

Acknowledged by:

Head of Department of Living Resources Management

Dr. Ir. Sulistiono, MSc.

Dean of Graduate School

Prof. Dr. Ir. Khairil A. Notodiputro, MS.

FOREWORD

Praise is to bestow to Allah, with His blessing this dissertation is finalized. The title of the research is Community-Based Coral Reef Management in Small Islands: A Social Capital Analysis.

This dissertation is produced from numerous supports from and discussions with many parties: academic supervisors and lecturers, scholars, family and friends, research assistants, key informants, fishers, boatmen, villagers, and many people who assisted me in various ways throughout the study and research period. Beyond my imagination, this research has given me an opportunity to interact with various people and learn so many new things. Allow me to express my gratitude to them.

Deep gratitude and appreciation are given to Dr. Ir. Akhmad Fauzi, MSc, Prof. Dr. Ir. Rokhmin Dahuri, MS, and Dr. Ir. Achmad Fahrudin, MS at Bogor Agricultural University, and Prof. Dr. Hellmuth Lange at University of Bremen, Germany. Their supports and guidance have never been halted. The process of study and research shows me how teachers and their patience are essential in their role in improving student’s mind and capacity.

A special thank is acknowledged for Dr. Ir. Mennofatria Boer, DEA as the Secretary of Study Program, as well as all members of the Academic Committee of Coastal and Marine Resources Management Study Program, who have assisted me since the beginning of the study and research. Moreover, substantial discussions and support have always been offered by Dr. Luky Adrianto and Dr. Arif Satria.

The study would not have been possible without the scholarship from the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), under the Scholarships for Young Indonesian Marine and Geoscience Researchers. Particular gratitude is given for Dr. Joachim Schneider and Ms. Irmgard Kasperek at DAAD Bonn, Ms. Endah C. Anggoro at DAAD Jakarta Office, and Mrs. Ilona Krueger-Rechmann, Director of DAAD Jakarta Office.

Scholars and colleagues at artec (Research Centre for Sustainability) and ZMT (Centre for Tropical Marine Ecology) had extended their hospitality and assistance during the research period at University of Bremen in 2003-2006. Special thanks are given to Dr. Christine Eifler, Dr. Winfried Osthorst, Ms. Brigitte Nagler, Mr. Heiko Garrelts, Mr. Andreas Rau, Ms. Andrea Meier, Ms. Antje Michallik, and Ms. Marianne Chr. Cyris at artec; Dr. Andreas Kunzmann at ZMT who had introduced me to Prof. Hellmuth Lange and Prof. Rokhmin Dahuri; also Dr. Marion Glaser, Dr. Gesche Krause, Dr. Eberhard Krain, Prof. Dr. Venugopalan Ittekkot, and Ms. Milena Arias-Schreiber. Additionally, I thank to Dr. Regina Birner at University of Göttingen who had assisted me in shaping the initial research design.

Special gratitude is given to Dr. Ramalis Subandi Prihandana, who convinced me to take up the opportunity to continue studying and argued that study is an enjoyable journey. Without her compelling tone, I might not have gone through a PhD learning experience. Our get-together and discussions since 1997 in Bandung, The Hague, or Jakarta have always inspired and motivated me.

Andi Nur Jaya had assisted me in various ways during data collection in Taka Bonerate. NGO colleagues in South Sulawesi and Jakarta had provided valuable information and data about the islands, particularly Kapoposang; therefore I thank Kemal Massi, Salam, Dodi, Ipunk, Zatriawan, A. M. Jufri, Nazruddin, and Adras. Staffs at Taka Bonerate MNP Office: Wawan, Cica, Nunu, Hikmah, Marwah, Sunadi, Raduan, and Anto Fajar had facilitated data collection and sea transportation during my stay in Benteng city and Taka Bonerate islands.

Researchers at LIPI-Coremap had helped me a lot, especially Ms. Nurul Dhewani who introduced me to Taka Bonerate for the first time and allowed me to join their trip to Taka Bonerate, also Dr. Denny Hidayati, Ms. Irina Rafliana, and Dr. Sukarno. Staffs and volunteers at Terangi Foundation introduced me to marine life under water and gave me access to their library; therefore appreciation is extended to Tries Razak, Kiki Anggraini, and Heri. The Center for Coral Reef Studies at Hasanuddin University had allowed me to obtain data about the islands, in particular Barrang Caddi; therefore I thank Dr. Jamaluddin Jompa, Ms. Dewi Yanuarita, and Ratnawati. In addition, other researchers with whom I met accidentally in Makassar: Amelia Hapsari and Mercy Patanda, had offered lively discussions and encouragement.

Newly found families and friends have been present during the process. In the islands far away from home, I found the warmth and hospitality of countless fishers’ families. I hope this acquaintance has also given them some benefit too, otherwise I would feel just like all the people who use other people grieve for their own advantage. In particular, I express my gratitude to Pak Nur, Pak Jabbar, Pak Hamzah, Pak H. Burhan, Bu Hj. Indo Tang, Pak Coang, Bu Saenab, Pak H. Azis, and Bani who had accommodated me during my stay in the islands. By the same token, the caring and love from Indonesian families including their lovely children made my stay in Bremen a wonderful period. I specially thank to families of Pujianto and Gery Vidjaja. The friendship of the members of PPI Bremen and other German students: Ina Bausch, Isabel Götte, Olena Horban, and Farid Selmi, had offered me experiences other than study.

In addition, continuous friendship and support from the DAAD PhD scholarship holders and PhD students in Coastal and Marine Resources Management Study Program of Bogor Agricultural University have been encouragingly contributed to the dynamic process of the study. Daeng Taswin, Mas Erwin, Mas Agus, Lukman, Wiwin, Ine, and Pak Khusnul, I owed you a lot for the companionship while pursuing study and research in Germany and Indonesia.

Unconditional supports and continuing prays have always been given by my mother, father, sister, brother, parent-in-laws, sister-in-laws, brother-in-laws, and nieces in Jakarta, Jambi, Makassar and Menado. Data collection in South Sulawesi was smoothed with the presence of an extended family, especially my mother-in-law who always assisted me with logistical and administrative matters for the field works. She had supported an enjoyable stay in Makassar, even though I kept going for days or weeks to the islands and then bringing more papers and messiness home.

Finally, I dedicated the section to the person I care most. I thank my husband for the faith and support on the decision that I took, even tough that meant I had to travel a lot and we had to live apart across different continents and islands in the last three years. But never ending motivation, support and love have always been given for me to continue to move on.

H. Parmo Karyoredjo, SE, MM and Hj. Sudarni Wahyuningsih. She married with Rachmat Irwansjah, ST, MSc in 2002.

She finished her undergraduate study in Regional and City Planning, from Institute of Technology Bandung (ITB) in February 1999. The degree of Master of Arts (M.A.) was obtained in December 2001, in Development Studies, specialization of Public Policy and Administration, from Institute of Social Studies (ISS), The Hague, The Netherlands. The study was facilitated by a STUNED Scholarship. Since October 2003, she received a DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) Scholarship for Young Indonesian Marine and Geoscience Researchers, to continue a PhD study and research, under the supervision of professors and lecturers from Bogor Agricultural University, Indonesia and University of Bremen, Germany.

She had worked for the National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) in 1999-2000 and PT. Townland Indonesia Consultant in 2002-2003. Later on, she has been freelancing and volunteering in some NGOs in Indonesia and The Hague, Brussels, Bremen, as well as freelancing in some consultants in Indonesia.

TABLE OF CONTENT

Page

LIST OF TABLES ... xvii

LIST OF FIGURES ...xx

LIST OF APPENDIX... xxii

GLOSSARY AND ABBREVIATIONS ... xxiii

1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background... 1

1.2 Rationale of the Research ... 2

1.3 Research Questions, Hypotheses, and Research Objectives ... 4

Research Questions ... 4

Hypotheses... 4

Research Objectives... 5

1.4 Introduction to Chapters ... 6

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND: CORAL REEF ECOSYSTEMS, SOCIAL CAPITAL AND MANAGEMENT OF CORAL REEF RESOURCES 8 2.1 Benefits of and Threats to Coral Reef Ecosystems ... 8

Biological Characteristics... 8

Benefits of Coral Reef Ecosystems ... 9

Threats to Coral Reef Ecosystems ... 10

2.2 Coral Reef Ecosystem as Common-Pool Resources ... 12

2.3 Institutions Governing Common-Pool Resources... 13

Property Rights ... 14

Local Institutions and Self-Governance ... 15

Collaborative Management... 16

Integrated Coastal Management ... 18

2.4 Natural Resource Management and Social Capital... 20

Towards An Understanding of Social Capital ... 20

Common-Pool Resources and Social Capital... 21

Potential Role of Social Capital in Coral Reef Management ... 21

3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

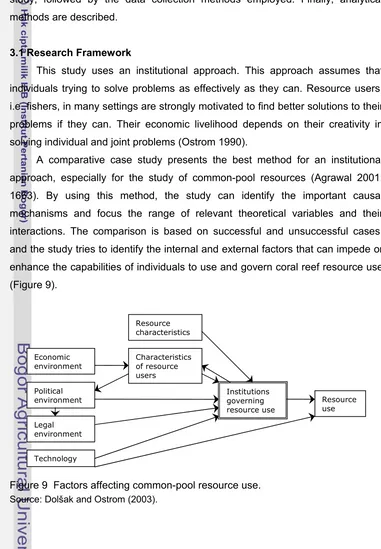

3.1 Research Framework ... 25

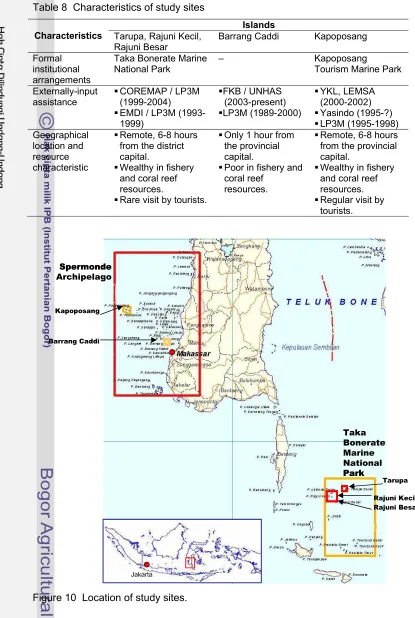

3.2 Selection of Study Sites... 26

3.3 Data Collection Method ... 29

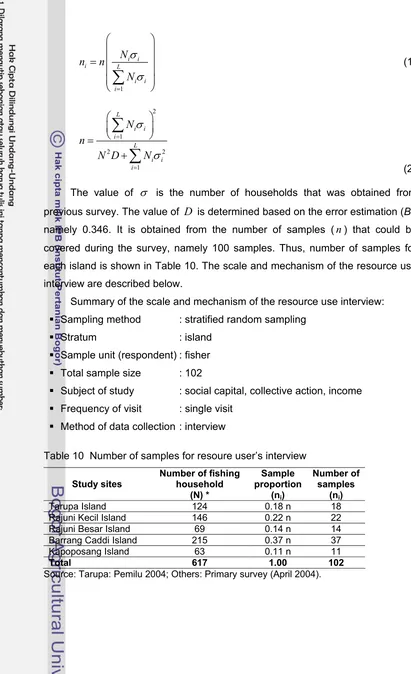

Population Survey... 29

Resource User Interview ... 29

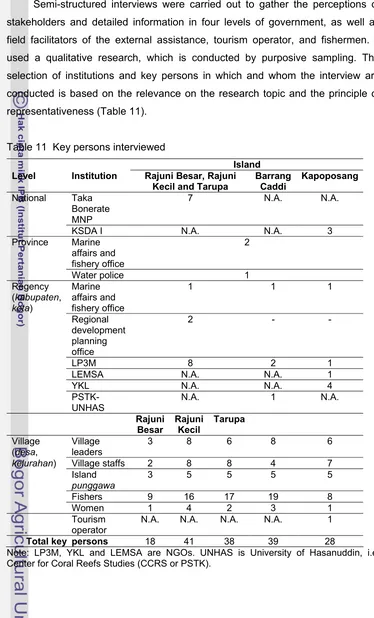

Key Person Interview... 31

Group Discussion ... 32

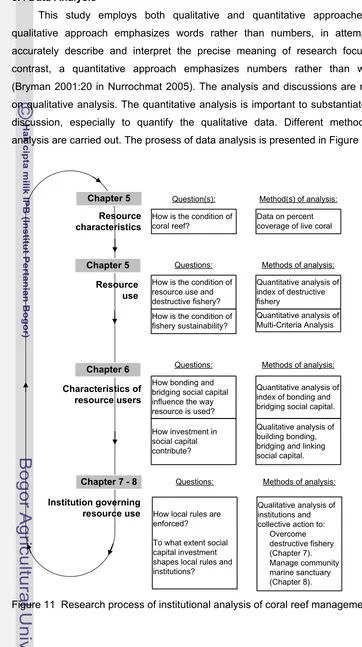

3.4 Data Analysis... 33

Calculating Index of Destructive Fishery ... 34

Participatory Multi-Criteria Analysis (MCA)... 34

Calculating Index of Bonding and Bridging Social Capital... 36

Statistical Analysis ... 37

4 GENERAL CONDITIONS OF STUDY SITES 4.1 Resource Conditions ... 40

Spermonde Archipelago: Barrang Caddi and Kapoposang Islands ... 40

Location and Accessibility... 41

4.2 Institutional Arrangements ... 42

Taka Bonerate Atoll ... 42

Kapoposang ... 43

Barrang Caddi... 44

Resource Users ... 44

4.3 Community Livelihoods... 44

Coastal Fishery... 46

Type of Fishes and Marine Biota ... 46

Fishing Gears ... 48

Seasonal Calendar ... 50

4.4 Socio-economic Conditions ... 51

Education Level and Infrastructure ... 51

Health Infrastructure ... 52

Electricity ... 52

4.5 Population: Ethnicity and Origin... 53

Taka Bonerate Atoll: Rajuni and Tarupa Islands ... 54

Spermonde Archipelago: Kapoposang and Barrang Caddi Islands ... 55

5 CORAL REEF, DESTRUCTIVE FISHING, AND FISHERY SUSTAINABILITY 5.1 Status of Reefs ... 57

Taka Bonerate Atoll ... 57

Barrang Caddi and Kapoposang ... 59

History of Destructive Fishing ... 60

Destructive Fishing 2004 ... 61

Destructive Fishing 2005 ... 63

Taking Coral ... 64

Index of Destructive Fishing ... 65

5.3 Status of Fishery Sustainability... 67

Generation of Indicators ... 69

Weight of Indicators ... 70

Average Weight ... 70

Relative Weight... 71

Group Interests ... 72

Sustainability Index of Criteria ... 73

5.4 Destructive Fishing and Fishery Sustainability ... 74

6 SOCIAL CAPITAL, ITS INVESTMENT, AND DESTRUCTIVE FISHING 6.1 Measuring Social Capital ... 76

Dimensions of Social Capital ... 76

Causal Mechanism of Social Capital ... 78

Social Capital Investment ... 78

6.2 Bonding and Bridging Social Capital ... 80

Generation of Bonding and Bridging Social Capital... 82

Index of Bonding and Bridging Social Capital... 84

Interests of Distinctive Networks... 86

Vertical Bonding Social Capital: Punggawa-Sawi... 87

Fishing Trading Network... 89

Discussions... 91

6.3 Social Capital Investment ... 91

Taka Bonerate Atoll: Rajuni and Tarupa Islands ... 92

Barrang Caddi Island ... 93

Kapoposang Island ... 93

6.4 Building Social Capital for Collective Action ... 94

Building Bonding Social Capital... 95

Building Bridging Social Capital... 97

Building Linking Social Capital... 97

6.5 Cognitive Social Capital: Trust... 99

Community Trust ... 99

7 INSTITUTIONS, RULES, AND COLLECTIVE ACTION: REDUCING DESTRUCTIVE FISHING

7.1 Managing Sustainable Resource: Role of Institution and Collective

Action... 102

Commons and Institutions ... 102

Collective Action and Self-Governance ... 103

Two to Tango: Formal and Community Institutional Capacity ... 105

7.2 Formal Monitoring and Law Enforcement... 106

Formal Coastal Property Regime ... 107

Monitoring in Marine National Park: Taka Bonerate ... 108

Monitoring in Tourism Marine Park: Kapoposang... 110

Monitoring in Barrang Caddi ... 110

7.3 Institutional Analysis of Formal Law Enforcement ... 111

Lack of Ability to Prevent Free Rider ... 111

High Management Cost ... 112

Deficiency to Sanction ... 112

Decrease Trust to Law Enforcement ... 113

7.4 Fishers’ Rules and Collective Action in Coastal Fishery... 114

Fishers’ Rules in Response to Externalities ... 114

Impact of Social Capital Investment: Collective Action in Conservation 116 Conservation Group... 119

7.5 Monitoring Individual Compliance... 121

Community Monitoring... 122

Problem of Scale in Achieving Credible Commitment ... 124

Cost of Monitoring... 125

Tolerance and Fairness ... 125

Higher Order Dilemma: Local Sanctioning ... 127

7.6 Problem of Institution Supply: Why Local institution Does Not Last Longer? ... 129

Discount Rate: Fishers’ Perception on Future Resource Stock... 129

Interests among Community-level Decision Makers... 131

Policy Impediments... 133

7.7 Social Capital, Local Rules and Destructive Fishing ... 134

Analysis of Logistic Regression ... 134

Formal Rules, Local Rules and Destructive Fishing ... 135

8 RULES, RULE MAKING AND RULE BREAKING: PROTECTION OF COMMUNITY MARINE SANCTUARY 8.1 Background... 138

8.2 Sanctuary Establishment ... 138

8.4 Barrang Caddi... 140

Rules ... 140

Monitoring ... 141

Distribution of Cost ... 142

Benefit ... 143

8.5 Rajuni and Tarupa ... 143

Rules ... 144

Monitoring and Local External Enforcement... 145

Credible Commitment and Sanction ... 146

Costs and Benefits... 146

Formal Recognition... 147

8.6 Problems in Rules Enforcement ... 147

9 AGENT-BASED MODELLING OF SOCIAL CAPITAL AND DESTRUCTIVE FISHING 9.1 Introduction ... 150

9.2 Simulation Experiment... 151

The Model of Destructive Fishing and Social Capital ... 152

Sensitivity Analysis ... 156

9.3 Sanction, Fish Price, Production Cost, and Destructive Fishing... 159

10 SUMMARY, CONCLUSION, AND POLICY RECOMMENDATION 10.1 Summary ... 160

10.2 Conclusion ... 166

10.3 Policy Recommendation ... 168

10.4 Recommendation for Further Study... 171

LIST OF TABLES

Page

1 Total net benefits and losses due to threats of coral reefs ... 12

2 Four classes of property rights holders in relation to their bundles of rights... 15

3 Differences between the North and South countries on the important variables for success delivery of ICM program... 19

4 Complementary categories of social capital ... 20

5 Social capital and fisheries governance ... 23

6 Methods of social capital investment... 24

7 Case studies... 27

8 Characteristics of study sites... 28

9 Number of respondents on the population interview ... 29

10 Number of samples for resource user’s interview ... 30

11 Key persons interviewed ... 31

12 Respondents of participatory MCA... 32

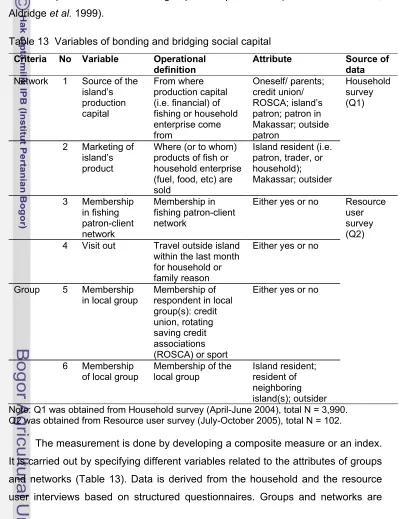

13 Variables of bonding and bridging social capital ... 36

14 Variables for each indicator ... 38

15 Accessibility to the islands... 41

16 Formal institutional arrangements of studied islands ... 42

17 Occupation of working population ... 45

18 Fish and other marine biota caught by resident fishers ... 47

19 Fishing gears utilized by resident fishers... 48

20 Approximate start of blast and poison fishing in study sites ... 49

21 Seasonal calendar... 50

22 Fishers activities in different seasons... 50

23 Level of education ... 52

24 Establishment of island-wide electricity system ... 53

25 Population of study sites... 53

26 Population ethnicity ... 54

27 History of Rajuni and Tarupa Islands ... 55

28 History of Kapoposang ... 56

29 Classification of quality of reef... 57

31 Average percent of hard coral cover at Taka Bonerate MNP in 2000 ... 58

32 Coral reef condition in South Sulawesi in 2003 ... 59

33 Coral cover in Barrang Caddi Island in 2005... 59

34 Type of marine habitat in Kapoposang TMP ... 59

35 Fishing gears in each island (2004)... 62

36 Use of bomb fishing in each island (2005) ... 64

37 Use of poison fishing in each island (2005)... 64

38 Coral taking in each island (2005) ... 65

39 Means and test of variance of destructive fishing in 2004 and 2005... 66

40 Index of destructive fishing in 2004 and 2005 ... 66

41 List of sustainability indicators for the fishery system ... 69

42 Dimensions of social capital by different authors ... 78

43 Institution building of local fishers... 79

44 Variables of bonding and bridging social capital ... 81

45 Value each variable of bonding and bridging social capital... 83

46 Bonding and bridging social capital ... 85

47 Fish trading network ... 90

48 Strategies and activities of community-based externally-input assistance .... 92

49 Influence of state capability and social capital on institutional choice ... 105

50 Comparative policy analysis of community and institutional capacity ... 106

51 Stakeholder analysis in coastal monitoring and management ... 107

52 Zoning system for capture fisheries... 108

53 Fisher rules addressing technological and assignment problems ... 115

54 Fishers’ collective action in resource use ... 117

55 Fishers’ monitoring driven by external assistance... 122

56 Authority of local monitors and park rangers in Taka Bonerate MNP and Kapoposang TMP... 124

57 Characteristics of resource use ... 132

58 Resource use and institutions governing resource use ... 136

59 Community marine sanctuaries ... 139

60 Fishing in sanctuary and level of trust ... 140

61 Simulation result to observe the impact of sanction ... 156

62 Simulation result to observe the impact of fish price ... 157

63 Simulation result to observe the impact of production cost (1) ... 157

64 Simulation result to observe the impact of production cost (2) ... 158

LIST OF FIGURES

Page

1 The relationship between the chapters in this thesis ... 6

2 Types of coral reefs ... 9

3 Total economic value of coral reef uses ... 10

4 Sources of coral reef degradation ... 11

5 A general classification of goods ... 12

6 Factors affecting common-pool resource use ... 14

7 Spectrum of co-management arrangements ... 17

8 Institutions for cross-scale linkages... 24

9 Factors affecting common-pool resource use ... 25

10 Location of study sites ... 28

11 Research process of institutional analysis of coral reef management... 33

12 Number of fishers using bomb and poison ... 63

13 Fishing gears of each island... 63

14 Frequent poison and bomb fishing by resident fishers ... 64

15 Coral taking in each island ... 65

16 Index of bomb and poison fishing in 2004 and 2005 ... 67

17 Estimated average weight for fishery sustainability indicators ... 70

18 Estimated relative weight for fishery sustainability indicators ... 71

19 Indicator importance (average weight) based on group interests... 73

20 Sustainability index of criteria of fishery system ... 74

21 Relationships between three indicators of social capital ... 78

22 Index of bonding and bridging social capital... 85

23 Index of vertical bonding social capital ... 88

24 Perceived benefits of external assistance on fish and coral reef condition ... 95

25 Level of community trust and frequency of bomb and poison fishing... 99

26 MCS System at Taka Bonerate MNP between 2002-2003 ... 109

27 A cycle of collective action by fishers ... 116

28 Performance of local conservation group in all islands (A) and each island (B) ... 120

29 Existence of local conservation group vis-à-vis frequent poison fishing... 121

30 Fishers’ monitoring on blast or poison fishing ... 122

32 Tolerance, fairness, forbid, and agree on sanction destructive fishing... 128 33 Poison fishing; benefit to coral reef condition; benefit to size of fish ... 131 34 Fishing in community sanctuaries in all islands (A) and each island (B) ... 139 35 Establishment and protection of community marine sanctuaries in

Barrang Caddi ... 140 36 Establishment and protection of community marine sanctuaries in

LIST OF APPENDIX

Page

GLOSSARY AND ABBREVIATIONS

Binmas Law enforcement officer of the police department assigned and resided in village

Binsa, babinsa Law enforcement officer of the army forces assigned and resided in village

BKSDA Natural Resource Conservation Office, Ministry of Forestry BPD Village representative body (Badan Pertimbangan Desa) BTNTB Management authority of Taka Bonerate Marine National Park

(Balai Taman NasionalTaka Bonerate)

CCRS Center for Coral Reef Studies of Hasanuddin University (Pusat Studi Terumbu Karang, PSTK)

Coremap Coral Reefs Rehabilitation and Management Program DKP Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries

FKB Coastal Partnerships Forum (Forum Kemitraan Bahari) FORMAK Community Forum for Conservation (Forum Masyarakat

Konservasi), Rajuni Besar Island

KCC Kapoposang Care Consortium (Konsorsium Pemerhati Kapoposang), a consortium of two NGOs

Kabupaten District Kecamatan Sub-district

KUHAP Criminal code procedures

LEMSA Indonesian Maritime Institute (Lembaga Maritim Nusantara), NGO

LIPI Indonesian Institute of Sciences

LP3M Institute of Rural, Coastal and Community Studies (Lembaga Pengkajian Pedesaan Pantai dan Masyarakat), NGO

MCS Monitoring, Controlling and Surveillance MNP Marine National Park of Taka Bonerate Punggawa Capital owner, patron or boss

ROSCA Rotating saving credit associations (arisan) Sawi Low level of fisherman

TMP Tourism Marine Park of Kapoposang

1.1 Background

Coral reef is an important marine resource as a source of biodiversity, a breeding ground for fishes and other marine biota, and supplying benefits for human communities, especially those who dependent on marine resources, i.e. fishermen and coastal communities. Indonesia has approximately 51,000 square kilometers of coral reefs. Most of these reefs are fringing reefs, adjacent to the coastline and easily accessible to coastal communities (Burke et al. 2002). However, a modeling of ‘Reefs at Risk in South East Asia’ suggests that human activities threaten over 85% of Indonesia’s coral reefs, with nearly one half at high threat. Threat to coral reef ecosystem includes fishing using explosives and poison which have been dated back since the Second World War (Pet-Soede et al. 1999). Destruction of coral reef due to these practices can contribute to weakening spawning aggregation for various reef fish and biota.

Problems faced within ocean fishery and coral reefs are associated with the nature of this resource, which is categorized as commons1. The common-pool resources shares two characteristics: (1) it is highly costly or impossible to exclude potential users from access to and appropriate the resource; and (2) the resource unit appropriation will subtract the resource stock available. Due to these characteristics, commons is confronted with problems of free-rider and of overuse. This situation is called “tragedy of the commons” by Hardin (1968), which occur when the resource is open access.

To avoid the problem of overuse and to increase efficiency and sustainability of resource use over time, common-pool resource should be governed. It can be governed by users themselves or external authorities (Ostrom 1990; Ostrom et al. 1994; Dolšak and Ostrom 2003). A top-down approach to coastal fishery is done through command and control, which include among others fishing license and sea patrols. However, these have only been reducing blast and poison fishing during the patrols, but not eliminating them; while patrol at the sea is expensive and difficult to be implemented effectively

1

(Pet-Soede et al. 1999). Many had argued that powerful economic forces and the socio-economic frameworks of the fishermen are driving the practices continued (Cesar 1996; Pet-Soede et al. 1999; Fauzi and Buchary 2002).

A complementary approach in responding to the problem is by promoting the sense of stewardship and the collective action of local fishers communities over the resources where their livelihood dependent upon. Resource users are proved to be capable of managing common-pool resource, including coastal fishery (Berkes 1985; Ostrom 1990; Dolšak and Ostrom 2003). Managing coastal fishery means managing the way the resource is harvested in the fishing grounds, where coral reefs situated.

1.2 Rationale of the Research

Many programs and projects had been promoted by the government and supported by multilateral or bilateral donors, to promote sustainable coastal and marine resources management. These initiatives include Marine Resources Evaluation Project (MREP), Coastal Community Development and Fisheries Resource Management (CO-FISH), Marine and Coastal Resource Management Project (MCRMP), which were funded by ADB, as well as Coral Reefs Rehabilitation and Management Program (COREMAP) that funded by ADB and the World Bank.2 Despite various initiatives to halt the destruction of coral reefs

and to promote sustainable coastal and marine resource use, which also endorsed by the community, the state of coral reefs in Indonesia remains poor or is getting worse. COREMAP estimation suggests that in 2000 overall within Indonesia only 6.2% of the coral reefs remain in excellent condition with coral coverage between 76-100% (Hanson et al. 2003; Dahuri 2003: 209).

On the other hand, the presence of social capital is considered important in promoting sustainability of resource use (Ostrom et al. 1994; Grafton 2005). Thus, it is appealing to investigate to what extent social capital has been promoted in and affected the coastal management projects, particularly in coral reef use, management, and condition. Social capital is viewed as one important feature for long-enduring self-governance of common-pool resources. Many empirical studies showed that common-pool resources can also be used and

2

managed sustainably by the resource users themselves (Berkes 1985; Ostrom 1990).

In this regard, social capital is defined as “the capacity of communities to cooperate for managing natural resources in a sustainable way” (Birner and Wittmer 2004). Moreover, with regard to dimension of social capital, it is generally understood that social capital has some combination of role-based or rule-based (structural) and mental or attitudinal (cognitive) origins (Coleman 1988; Putnam 1993; Serageldin and Grootaert 2000). Cognitive social capital embraces norms and trust, while structural social capital consists of rules, networks, and organizations (Uphoff 2000).

Another definition of social capital is trust, norms of reciprocity, and networks that facilitate the formation of collective action and institution (Grootaert et al. 2003). Trust, shared norms, and norms of reciprocity are important for the establishment of institutional arrangements. Shared norms can reduce the cost of monitoring and sanctioning (Ostrom 1990). Trust makes social life predictable, while it creates a sense of community, and it makes it easier for people to work together (Folke et al. 2005). These features known as social capital are important to lubricate or facilitate cooperation among individuals to develop and implement rules or institutions, and resolve collective action problems that are needed to manage natural resources on a sustainable way (Ostrom 1990; Agrawal 2001).

Based on this perspective, social capital may contribute to sustainable resource use, including that of common-pool resources such as coastal resources and coral reefs. However, whereas social capital is defined differently by various authors and studies, it is largely disputable on which mechanisms social capital has been manifested into sustainable resource use. This endeavor resembles to what had been investigated by Krishna (2002), even though the focus was not on the natural resource management, notwithstanding coral reefs management.

2001); building trust and the growth of social network (Grafton 2005). This investment is considered to promote local rules or institution to govern coral reef resources, therefore improve sustainable coral reef resource use. The capacity building of local communities in natural resources management is at the same time regarded as social capital investment.

Following this emerging perspective, a community-based management has been promoted by local NGOs, university, and national and regional government, in small islands in South Sulawesi to spur shared stewardship among resource users. It had advocated collective action of local fisher communities to promote among others, environmentally-friendly fishing practices and establishment of community marine sanctuaries. Therefore, it is appealing to investigate to what extent investment in social capital of fisher communities can alleviate the problem of overuse that generally associated with common-pool resources, and succeed in promoting durable collective action and institutional arrangements to govern the resource.

1.3 Research Questions, Hypotheses, and Research Objectives

Research Questions

Previous section has described that the theories on common-pool resources and natural resource management propose that social capital might play a role in achieving sustainable resource use. Based on this perspective, the following questions will be specifically posed on this study:

1. How social capital contributes to sustainable resource use?

2. Which dimensions of social capital, in terms of bonding, bridging and linking social capital, contributes to sustainable resource use and management?

3. To what extent social capital investment of fisher communities delivers collective action and institutional arrangements to govern sustainable resource use?

Hypotheses

Along with the above research questions, the following hypotheses will be specifically sought on this study:

2. Bonding, bridging and linking social capital will promote sustainable coral reef resource use.

3. Investment in social capital will improve sustainable coral reef resource use.

Research Objectives

A comparative study is carried out in several small islands situated in Taka Bonerate Atoll and Spermonde Archipelago, South Sulawesi, which aims to assess to what extent social capital as well as investment in social capital of fisher communities contribute to sustainable coral reef resource use. The specific objectives of the study are:

1. To investigate to what extent social capital contributes to sustainable coral reef resource use.

2. To investigate to what extent the dimensions of social capital, in terms of bonding, bridging and linking social capital, contributes to sustainable coral reef resource use and management.

3. To investigate to what extent social capital investment of fisher communities delivers collective action and institutional arrangements to govern sustainable coral reef resource use.

In order to investigate social capital and its relation to institutional arrangements of coral reef resource use at local level, the research framework must include the analysis of factors influencing resource use. An institutional analytical framework analyzing factors affecting resource use acknowledges that the use of coral reef resource is affected by formal and informal institutions governing its use (Dolšak and Ostrom 2003: 10). Formal institution includes government laws and rules, and their enforcement. Alternatively, informal institution is usually characterized by non-written rules or code of conducts accepted by a specific group of people. The establishment and endurance of institution arrangements are affected by the characteristics of resource system and of resource users or fisher communities.

craft rules. Third, how rules, institutional arrangements and collective action have been created by fisher communities are explored. The institution governing resource use is likely to influence the way resource is utilized, and then can explain the differing practices of destructive fishing and fishery sustainability across the studied islands.

Figure 1 The relationship between the chapters in this thesis.

Source: Adapted from Dolšak and Ostrom (2003).

1.4 Introduction to Chapters

Chapter two of this thesis presents a literature review. It begins with an overview of the characteristics and problems associated with common-pool resource, as well as the potential institutional arrangements to alleviate the problems. Next, it discusses co-management and stakeholder collaboration for integrated coastal zone management (ICZM). The significant and determinants of social capital in natural resource management and common-pool resources are then described.

A research methodology is presented in chapter three. It explains the research framework and the consideration of selecting five small islands for this study, followed by methods of data collection. Finally, analytical methods are described.

Chapter four describes the condition of study sites. The description focuses on the island fisher communities. It shows the very nature and situation where these communities live: their livelihoods, coastal fishery, origin and ethnic groups, as well as social infrastructure.

Institution governing resource use

Resource characteristics

Characteristics of resource users

Chapter 5 Destructive fishing. Fishery sustainability.

Chapter 6

Bonding, bridging, linking social capital. Investment in social capital.

Chapter 4

Resource characteristics.

Chapter 7, 8, 9

Rules, collective action and institution.

Chapter five starts with a discussion of the empirical findings: explaining the condition of resource use in each island, specifically the extent of destructive fishing, as well as fishery sustainability of each island.

The characteristics of resource users are examined in chapter six. It covers the cognitive and various dimensions of social capital. Further, social capital investment and its impact to collective action are investigated.

Chapter seven and eight explores how and about rules, institutional arrangements and collective action have been crafted by the fisher communities. Chapter seven also includes the analysis of formal institutional arrangements. Chapter eight focuses on community marine sanctuary, while chapter eight examines destructive fishing. This analysis then explains the differing practices of destructive fishing and fishery sustainability across the studied islands.

Chapter nine presents a simulation of resource utilization using computer tools. The simulation experiment uses an agent-based modelling to understand the dynamics impact of social capital on destructive fishing and fishery.

Capital and Management of Coral Reef Resources

This chapter presents theoretical background about the characteristics of coral reef ecosystems, as well as institutional perspective of natural resources and natural resource management, including coral reef resources. The relationships between ecological and social systems is due to the fact that human population are living in, on and from natural resources, including coastal and marine resources. The ecological system of natural resources is dynamic. The ecological system is vulnerable and has a characteristic of resilience. Human seek to understand natural dynamic in order to be able to take benefit, but without deteriorating it. They try to investigate how and to what extent their rate of exploitation is acceptable for the resource system. This is the main idea of sustainable development (WCED 1987). The societal responses to this endeavor is evolving: from state ownership and regulation on resource use to community-based management; and now increasingly efforts have been paid to collaborative management between government and community, as well as integrated coastal management, in order to bring together various knowledge and expertise to understand and tackle issues of the ecological and social systems associated with coastal and marine resources.

2.1 Benefits of and Threats to Coral Reef Ecosystems Biological Characteristics

They can only grow in warm, well lit waters and require a solid surface on which to settle. A change of environmental conditions such as higher temperatures, a change in salinity, or disease can cause coral polyps to expel the algae. This makes coral totally white or known as coral bleaching, and when the bleaching is irreversible, then the coral dies (Spalding et al. 2001: 15; Zubi 2004).

Coral reefs consist of four main types, namely fringing reefs, barrier reef platform reefs, and atolls (Figure 2). Fringing reefs develop in shallow waters along the coast of tropical islands or continents. The corals grow outwards towards the open ocean. Fringing reefs in Indonesia are located in the southern coast of Java, Lombok, Sumbawa, East Nusa Tenggara and Papua (Dahuri 2003). Barrier reefs are structures rising up from a deeper base at some distance from the shore, with a lagoon separating them from the coast. Barrier reef can be found in Central Sulawesi and East Kalimantan. Bank or platform reefs are reefs with no obvious link to a coastline that usually lie in sheltered seas and quite far offshore. They are flat-topped with small and very shallow lagoons. Atolls are rings of reef and typically have a shallow, sandy, sheltered lagoon in the middle. They can be found in Taka Bonerate in South Sulawesi (ibid).

Figure 2 Types of coral reefs.

Source: Zubi (2004).

Benefits of Coral Reef Ecosystems

Coral reefs offer various functions that provide a number of goods and services, such as fisheries, tourism, coastal protection, biodiversity, research and medicinal use (Dahuri et al. 1996; Cesar 1996; Bunce et al. 2000: 208; Spalding et al. 2001:47-55). The economic value of coral reefs can be calculated based on

(a) Fringing reef (b) Platform reef

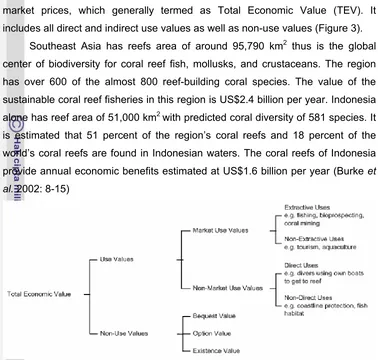

market prices, which generally termed as Total Economic Value (TEV). It includes all direct and indirect use values as well as non-use values (Figure 3).

Southeast Asia has reefs area of around 95,790 km2 thus is the global center of biodiversity for coral reef fish, mollusks, and crustaceans. The region has over 600 of the almost 800 reef-building coral species. The value of the sustainable coral reef fisheries in this region is US$2.4 billion per year. Indonesia alone has reef area of 51,000 km2 with predicted coral diversity of 581 species. It

[image:33.612.130.508.76.436.2]is estimated that 51 percent of the region’s coral reefs and 18 percent of the world’s coral reefs are found in Indonesian waters. The coral reefs of Indonesia provide annual economic benefits estimated at US$1.6 billion per year (Burke et al. 2002: 8-15)

Figure 3 Total economic value of coral reef uses.

Source: Bunce et al. (2000).

Threats to Coral Reef Ecosystems

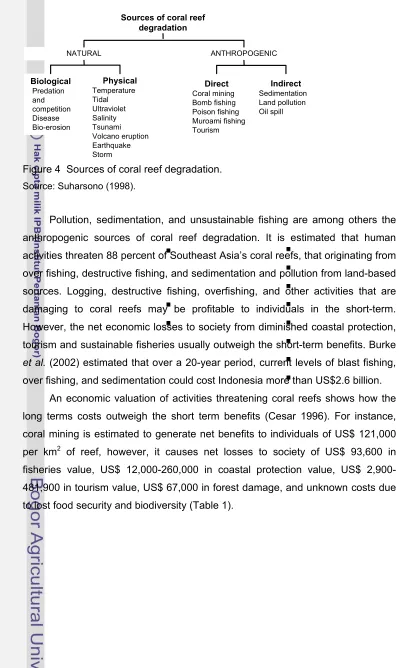

Sources of coral reef degradation

NATURAL ANTHROPOGENIC

Biological

Predation and competition Disease Bio-erosion

Physical

Temperature Tidal Ultraviolet Salinity Tsunami Volcano eruption Earthquake Storm

Direct

Coral mining Bomb fishing Poison fishing Muroami fishing Tourism

Indirect

[image:34.612.110.509.69.737.2]Sedimentation Land pollution Oil spill

Figure 4 Sources of coral reef degradation.

Source: Suharsono (1998).

Pollution, sedimentation, and unsustainable fishing are among others the anthropogenic sources of coral reef degradation. It is estimated that human activities threaten 88 percent of Southeast Asia’s coral reefs, that originating from over fishing, destructive fishing, and sedimentation and pollution from land-based sources. Logging, destructive fishing, overfishing, and other activities that are damaging to coral reefs may be profitable to individuals in the short-term. However, the net economic losses to society from diminished coastal protection, tourism and sustainable fisheries usually outweigh the short-term benefits. Burke et al. (2002) estimated that over a 20-year period, current levels of blast fishing, over fishing, and sedimentation could cost Indonesia more than US$2.6 billion.

An economic valuation of activities threatening coral reefs shows how the long terms costs outweigh the short term benefits (Cesar 1996). For instance, coral mining is estimated to generate net benefits to individuals of US$ 121,000 per km2 of reef, however, it causes net losses to society of US$ 93,600 in

Table 1 Total net benefits and losses due to threats of coral reefs (present value; 10% discount rate; 25 year time-span; in 1000 US$; per km2)

Net Benefits

to Individuals Net Losses to Society

Threat ..

Total Net

Benefits Fishery

Coastal

Protection Tourism Food Security

Bio-

diversity Others Total Net Losses Poison

Fishing 33.3 40.2 0.0

2.6 -

435.6 n.q. n.q. n.q.

42.8 - 475.6 Blast

Fishing 14.6 86.3 8.9 - 193.0 2.9 -

481.9 n.q. n.q. n.q.

98.1 - 761.2 Coral

Mining 121.0 93.6

12.0 - 260.0

2.9 -

481.9 n.q. n.q. > 67.0

175.5 - 902.5 Sediment

(due to logging)

98.0 81.0 - 192.0 n.q. n.q. n.q. 273.0

Overfishing 38.5 108.9 - n.q. n.q. n.q. n.q. 108.9

Source: Cesar (1996). n.q. means not quantifiable.

2.2 Coral Reef Ecosystem as Common-Pool Resources

Benefits and threats to coral reef ecosystems are not exceptional, but also occur to other natural resources. An institutional perspective classified goods or resources based on two important attribute: exclusion and substractability. Using these attributes, there are four main types of goods or resources: private, public, toll or club goods, and common-pool resources (Figure 5). Ocean and its entrenched resources such as fishery and coral reefs are categorized as common-pool resources or commons. This resource shares two characteristics. The first characteristic relates to the cost of excluding potential users from access to the resource. Excluding potential users is impossible or highly costly. The second is substractibility or rivalry, which means that harvest or exploitation of the resource will subtract its amount for others to do the same.

Substractibility

Low High

Difficult Public goods Common-pool

resources Exclusion

Easy Toll goods Private goods

Figure 5 A general classification of goods.

Source: Ostrom et al. (1994).

is “substractibility problem”, and consequently the resource is prone to over exploitation or destruction (Berkes 2006). This situation is called “tragedy of the commons” by Hardin (1968). However, the term “commons” used by Hardin is meanwhile widely acknowledged to describe a “tragedy of open access” (Stillman 1975 in Berkes 1985; Birner and Wittmer 2003). A growing analysis on commons was evolved after this influential inquiry (see Berkes 1985; Ostrom 1990; Feeny et al. 1990).

The use of common-pool resource may also present negative externalities to those who do not benefit from such use. The benefits obtained by the appropriators may not be fitting to the social cost. Coral mining for house building can be detrimental for coral reef’s functional use as coastal protection which may result in coastal erosion. Destruction of coral reef due to illegal fishing practices can contribute to weakening spawning aggregation for various reef fish and biota. These two problems are identified as the “commons dilemma” (Ostrom 1990). It reflects a “social dilemma” that occurs when the short-term self-interest of individuals result in sub-optimal benefits at the aggregate of social level (Rudd 2001). Olson (1965) has investigated this issue that is widely known as “the Logic of collective action”.

2.3 Institutions Governing Common-Pool Resources

The problems associated with common-pool resources can be alleviated if it is governed in order to increase the efficiency and sustainability of resource use over time. An institution to govern common-pool resource has to deal with the threats of overuse and of free riding. Common-pool resource can be governed by users or external authorities. No matter who governs a particular common-pool resource, it is critical to regulate at least two broad aspects, namely (1) access to the resources, in order to lift free riding problem, and (2) rules governing resource use, in an attempt to elevate overuse problem and destructive utilization (Ostrom 1990; Feeny et al. 1990; Pomeroy and Berkes 1997; Dolšak and Ostrom 2003).

management and informal social norms (North 1990; Ostrom 1990). Institutions will shape incentives and actions taken by individuals.

Figure 6 Factors affecting common-pool resource use.

Source: Dolšak and Ostrom (2003)

Property Rights

The study on institution and resource management emphasizes the importance of property rights. Property right offers incentives for the right holders to access, withdraw, as well as manage the resources. Property is “a claim to a benefit (or income) stream”, whereas a property right is “a claim to a benefit that some higher body – usually the state – will agree to protect through assignment of duty to others who may covet, or somehow interfere with, the benefit stream” (Bromley 1992).

Generally, it is understood that at least there are four categories of property rights within which common-pool resources are held, namely open access, private property, communal property, and state property or state governance (Feeny et al. 1990). Moreover, another way of explaining property rights is the bundle of rights (Schlager and Ostrom 1992). Property-rights regimes in a given area can be distinguished among diverse bundle of rights that may be held by the users of a resource system. The bundle of rights includes use rights (i.e., access and withdrawal rights), rights to exclude others, rights to manage, and the right to sell. Moreover, it defines a property-rights schema ranging from authorized user, claimant, proprietor, and owner (Table 2).

Different bundles of property rights affect the incentives individuals face, the types of actions they take, and the outcomes they achieve. Authorized users possess no authority to devise their own rules of access and withdrawal. Because authorized users do not design the rules they are expected to follow,

Resource characteristics

Economic environment

Political environment

Legal environment

Technology

Characteristics of resource users

Institutions governing resource use

they are less likely to agree to the necessity and legitimacy of the rules. Claimants, owners and proprietors have rights of management, thus face stronger incentives than do authorized users to make current investments in resources, including on governance structures.

Table 2 Four classes of property rights holders in relation to their bundles of rights

Owner Proprietor Claimant Authorized

User

Access and withdrawal

X X X X

Management X X X

Exclusion X X Alienation X

Source: Schlager and Ostrom (1992: 252).

Local Institutions and Self-Governance

Organizing collective action and building institution governingcommon-pool resource use must resolve a common set of problems. These consist of “coping with free-riding, solving commitment problems, arranging for the supply of new institutions, and monitoring individual compliance with sets of rules” (Ostrom 1990: 28-29). In investigating how to address commons dilemma, the main objects of attention of scholars are generally on local communities, institutions, resources, and outcomes (Agrawal 2001). These studies investigate how some groups of individuals succeed in breaking out the trap inherent in the commons dilemma and are able to build and endure self-governance (ibid; Berkes 1985).

Nevertheless, pure communal property systems and community-based resource management are always embedded in state property systems and derive their strength from them. The user community is dependent on the enforcement and protection of local rights by higher levels of government. Even those community groups with well-functioning local management system are dependent on the central government for legal recognition of their rights and their protection against outsider (Berkes and Folke 1998). This corresponds to one of Ostrom’s design principles, namely a nested enterprise or legal recognition that provides a linkage of local institution with higher institutions. Therefore, the sharing of resource management responsibility and authority between users and government agencies, or co-management, is increasingly important.

Collaborative Management

Government is unable to manage resources on their own. However, the same is true for communities and resource users (Silva 2006: 8). A community-based approach can only resolve local problems that are restricted to locations where the project had been delivered, whereas the resource system itself is regional in nature, which is also utilized by resource users beyond local level. This touches the issue of multi-scale resources that necessitates multi-scale management. Most of resource management systems have some cross-level linkages and drivers at different levels, especially in a globalized world (Berkes 2006).

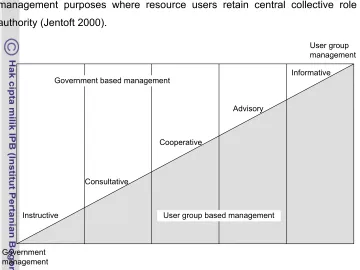

In responding the limitations of state-led and community-based approaches, a collaborative management (co-management) approach is sought (Dahuri et al. 2001; Satria 2002; Bengen 2004). Co-management is defined as the sharing of responsibility and authority between the government and the community of resource users to manage natural resources (Pomeroy and Williams 1994; Sen and Nielsen 1996). Co-management institutions are rooted as cross-scale institutions, in order to resolve cross-level issues that are pervasive in commons management (Berkes 2006).

Within a management spectrum, there exists a community-based co-management, where resource users become directly and formally involved in the management decision-making process through the delegation of regulatory functions to fishermen’s organizations, or to organizations especially designed for management purposes where resource users retain central collective role of authority (Jentoft 2000).

Figure 7 Spectrum of co-management arrangements.

Source: Sen and Nielsen (1996).

In promoting co-management that involves collaboration among multi-level of stakeholders, including exchanges of knowledge and communications, social capital is a necessary condition, where trust and networks are embedded. By the same token, the collaboration network for co-management provides an arena where social capital is enhanced (Folke et al. 2005; Grafton 2005). The extent, to which social capital is defined in this study, will be elaborated in the preceding section.

Co-management is acknowledged to resolve resource management issues that characterized in multi-scale systems. The approach underscores the collaboration of stakeholders, among others but not limited to government and resource users. It is applied to various types of resources. Moreover, for coastal resources that have distinct characteristics, another approach to resolve the complexity is through Integrated Coastal Management (ICM).

Government based management

User group based management Cooperative

Consultative

Instructive

Advisory

Informative User group management

Integrated Coastal Management

Integrated Coastal Management (ICM) is a societal approach to understand and resolve issues of ecological and social systems situated in the coastal and marine area. The coastal zone is area of land-sea interface, which contains various habitats and ecosystems which are dynamic in nature, located in marine and terrestrial environment; and is also characterized by competition for land and sea resources and space by various stakeholders, which often resulting in severe conflicts and destruction of the functional integrity of the resource system (Cicin-Sain and Knecht 1998; Bodungen and Turner 2001). Coastal and marine resources, including coral reef, are characterized by multi-benefits, which lead to multi-users and multi-interests. This situation calls for ‘integrated’ nature of decision making to achieve sustainability in social, economic, and ecological aspects.

Cicin-Sain and Knecht (1998) defines integrated coastal management as “a continuous and dynamic process by which decisions are made for the sustainability use, development, and protection of coastal and marine areas and resources” (Cicin-Sain and Knecht 1998: 39). The process is designed to overcome the fragmentation inherent in single-sector management approaches, in the splits in jurisdiction among different levels of government, and in the land-water interface. The main element of coastal governance is its integration across disciplines, stakeholder groups, and generations (Constanza et al. 1998). The term of integration in the coastal management embraces several dimensions: intersectoral integration, intergovernmental integration, spatial integration, science-management integration, and international integration (Cicin-Sain and Knecht 1998).

increased knowledge on natural resources and on relationship between natural resources and human activities.

Thus, ICM process must be dynamic and adaptive, in which policy-making is an iterative experiment acknowledging uncertainty, rather than a static “answer”, in order to cope with changing circumstances, increased knowledge of the behavior of coastal process and of human behavior, and changing government policies (Constanza et al. 1998; Turner and Bower 1999). This comes to the point that ICM shall be defined as an adaptive and dynamic policy-making process acknowledging uncertainty, with the purpose of achieving sustainable use of coastal and marine resources.

ICM has been applied in both developed and developing countries. The ICM application in a country depends on some influential contexts or variables. At least three important variables differentiate the ICM application in the North and South countries: (1) the governance capacity, authority and insitutional structures; (2) the pace of coastal change, driven by population pressures; and (3) the prospects of sustained financial support for a coastal management program, as is shown in Table 3 (Olsen 2003).

Table 3 Differences between the North and South countries on the important variables for success delivery of ICM program

North South

Governance capacity

Stable, harness rule of law; stringent zoning control

Low capacity and control

Speed of coastal change

Restrained High growth of unplanned urban

development Coastal

management funding

Subsidies, incentives from national and provincial government

No sustained source of core fund. Insufficient fund in provincial and municipal government. Thus, rely on external funds.

Source: Olsen (2003).

2.4 Natural Resource Management and Social Capital Towards An Understanding of Social Capital

Among various explanations on promoting sustainability of resource use over time is the presence of social capital. It is viewed as one important feature for long-enduring self-governance of common-pool resources. Social capital is identified as “the capacity of communities to cooperate for managing natural resources in a sustainable way” (Birner and Wittmer 2004). Coleman (1990) used social capital to refer to features of social organization such as trust, norms and networks. Ostrom (1990) used social capital to refer to the richness of social organization.

Social capital has been investigated by different disciplinary perspectives (Rudd 2001). Sociologists view social capital as with individual who can use social networks for personal economic advantage by acquiring resources within the network (Nee 1998; Burt 2000). Political scientists have a tendency to emphasize civil society and how it can enhance the level of general trust in a society. Having trust for strangers can make it easier to engage in transactions with them and, in aggregate, can enhance regional economic performance (see Putnam 1993). Economists see social capital in a boarder terms, as the institutional infrastructure that facilitates trade with strangers whom one might not trust at all. It is because property rights, money and banking, insurance, and the legal system reduce people’s reliance on personal trust, therefore reducing the transaction costs of trading (North 1990).

Table 4 Complementary categories of social capital

Structural Cognitive

Sources and manifestations

Roles and rules

Networks and other interpersonal

relationships

Procedures and precedents

Norms

Values

Attitudes

Beliefs

Domains Social organizations Civic culture

Dynamics factors Horizontal linkages

Vertical linkages

Trust, solidarity, cooperation, generosity

Common elements Expectations that lead to cooperative behavior, which produces

mutual benefits. Source: Uphoff (2000).

Correspondingly, Uphoff (2000) views social capital as having some combination of role-based or rule-based (structural) and mental or attitudinal (cognitive) origins. They are related and interactive, but distinguishable (Table 4).

Common-Pool Resources and Social Capital

With regard to common-pool resources, the institutional capacity of resource users is a necessary condition to resolve the problems associated with common-pool resources, i.e. free riding and overuse. However, based on detail study of several local commons, the capacity of resource users to design and enforce rules is not a sufficient condition to ensure resolution of complex dilemmas. Extending reciprocity to others, building trust to develop better rules, and accessing reliable information about complex process is important assets for resource users to craft and enforce institutions. Resource users who have developed forms of mutual trusts and social capital can utilize these assets to craft institutions that avoid the common-pool resources dilemma and arrive at reasonable outcomes (Ostrom et al. 1994).

In this respect, trust is one significant aspect for the establishment and endurance of institutional arrangements. Trust makes social life predictable, while it creates a sense of community, and it makes it easier for people to work together or cooperate (Folke et al. 2005). Trust, together with shared norms and norms of reciprocity are cognitive social capital, which is important to lubricate or facilitate cooperation among individuals to develop and implement rules or institutions, and resolve collective action problems that are needed to achieve societal goals (Coleman 1990; Putnam 1993; Ostrom et al. 1994).

Potential Role of Social Capital in Coral Reef Management

Many studies shows that in tropical developing countries, where formal institutions may be relatively weak, social networks remain important for controlling opportunism and solving social dilemmas in the inshore fisheries (Berkes 1986; Rudd 2001; Bavinck 2001). These studies focused on local-level or community-based fishery management, in which a well-defined boundary of social structure and interaction exist. In this way, the recurrent interactions among agents will form a local social structure may affect economic decisions and outcomes of resource users through three main mechanisms, as follows: 1. Information sharing. Frequent interactions in local organizations and

information sharing) and to exchange information about their daily lives (two-way information sharing).

2. Impact of transaction costs. Frequent and regular interaction in social settings, agents establish patterns of expected behavior and build bonds of trust. Combined with the possibility of sanctions, this lowers the likelihood of opportunistic behavior by agents that are in the same social structure, thus affect the level of transaction costs associated with many market exchanges. 3. Reduction of collective action dilemmas. Selective constraints are important

for agents as an incentive to participate in mutually-beneficial collective action (Olson 1965). Frequent and regular interactions in social settings lead to the development of institutions that can serve as such constraints, thus lowering the incentives of individual agents to free ride (Isham 2001: 4-5).

Three main dimensions of social capital with regard to social networks are distinguished: bonding, bridging and linking social capital (Woolcock 1998; Narayan 1999). Bonding social capital is strong bonds of social relationships which are endorsed among family members or among members of an ethnic group. Bridging social capital is weaker but more cross-cutting ties of social relationships, which can be found in relationships from different ethnic groups or acquaintances. Linking social capital are connections between those with differing levels of power or social status e.g. links between the political elite and the general public or between individuals from different social classes (Aldridge et al. 1999; Grootaert et al. 2003).

Based on definitions of bonding, bridging, and linking social capital, the impact of social capital in fishery management as pointed by Isham (2001) is restricted to the bonding social capital, which is networks and interactions among resource users within a local social boundary. However, local or community-based management is often faced challenges from external economic and political stresses which impinge upon those systems, such as loss of community control over the resource, commercialization of subsistence fisheries, rapid population-growth, and rapid technology-change (Berkes 1985). This challenge is related with the cross-level issues that are pervasive in commons management (Berkes 2006).

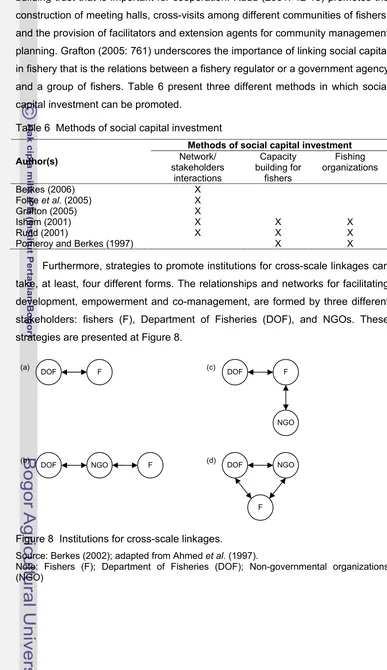

bridging and linking social capital. The diverse networks of social capital can contribute to different aspect of fisheries governance: promote conflict resolution, increase rule compliance, enhance flexibility to change, overcome rent-seeking behavior, and promote management options for uncertainty (Grafton 2005), as presented in Table 5.

Table 5 Social capital and fisheries governance

Type of social capital Aspects of fisheries

governance Bonding Bridging Linking

Conflict resolution X X X

Rule compliance X X X

Enhanced flexibility to change

X X

Rent-seeking behavior

X X

Management options with uncertainty

X X X

Source: Grafton (2005). Note: ‘X’ indicates the governance factor (row) is likely increasing in the number and quality of connections of the given type of social capital (column). In other words: social capital will increase governance factors.

Building and Investing in Social Capital

If social capital is a necessary condition to craft and enforce rules for common-pool resources (Ostrom et al. 1994), as well as for fisheries governance (Grafton 2005), therefore it is significant to acknowledge how improvement in social capital is to undertake. Another crucial consideration for social capital investment is to overcome the cross-level issues that are pervasive in commons management. Therefore, the role of cross-scale institutions is significant to provide a means to bridge the divide between processes taking place at different levels (Berkes