A Four-Year Tracking Study of Attitudes

and Self-Reported Behavior

Thomas J. Cosse´

UNIVERSITY OFRICHMONDTerry M. Weisenberger

UNIVERSITY OFRICHMONDHistorically, the proportion of the American public that expresses positive indicate that they support organ donation and transplantation

views about organ donation exceeds the proportion that actually signs an (Gallup, 1993), the positive views toward donation expressed

organ donor card (ODC). The public seems to say one thing but does by the public are not matched by action.

another. In July 1994, The Advertising Council, Inc., in conjunction with It is doubtful that the supply of cadaveric organs will ever

the Coalition on Donation, launched a major promotional campaign to fully meet the demand. In fact, artificial organs (Basu-Dutt et

educate the U.S. public about organ and tissue donation. This article al., 1997; Kaufmann et al., 1997), xenotransplantation, that

reports on a four-year study tracking attitude toward organ donation and is, organs from animals (Arundell and McKenzie, 1997), and

transplantation and its relationship with direct experience (knowing an even cloned organs (currently banned) may be the ultimate

organ recipient) and intermediate behaviors. The intermediate behaviors solution. In the meantime, however, the organ donation and

investigated are donating blood and signing an ODC. No significant transplantation community is actively seeking to increase the

changes were noted in attitude toward donation, but the proportion of number of posthumous donations. One program seeking to

individuals who had signed an ODC increased significantly.J BUSN RES increase donations is the national advertising and promotion 2000. 50.297–303. 2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. effort undertaken by the Advertising Council, Inc. and the

Coalition on Donation.

National Campaign for

A

ccording to the United Network for Organ Sharing(UNOS), the “# 1” issue confronting the transplanta-

Organ Donation

tion community is the critical shortage oftransplant-In 1993, The Advertising Council, transplant-Inc., (henceforth the Ad able organs (UNOS, 1998a). In fact, the Coalition on Donation

Council) and the Coalition for Donation (henceforth the Coali-(1998) describes the shortage as a public health crisis. During

tion) developed a multi-media national promotion campaign 1988, 27,805 patients in the United States were on the organ

to educate the public about organ and tissue donation. The waiting list and there were 4,084 cadaveric donors. By 1996,

overriding objective of the campaign is to increase the number the number of patients on the waiting list during the year had

of organ and tissue donors. The campaign was launched in nearly tripled to 72,836, but the number of cadaveric donors

July 1994 with the theme “Organ and Tissue Donation: Share had increased to only 5,417 (UNOS, 1998b). Although 20,354

your life. Share your decision.” It stresses the need to sign an organ transplants (cadaveric and living) were performed in

organ donor card and to inform family members of that deci-the United States during 1996, 4,022 patients—about 11 per

sion. During the campaign’s first year, $33.3 million of media day—died while on the waiting lists (UNOS, 1998b). It is

had been donated. In the next year, over $47 million was surprising that the number of cadaveric donors has not

in-donated. (Nathan, 1997). creased over the years, as there are over 2 million deaths

This article reports the findings of a four-year study tracking annually in the United States. While most Americans (85%)

community attitude and behavior in metropolitan Richmond, Virginia, concurrent with the Ad Council/Coalition campaign.

Address correspondence to Thomas J. Cosse, The E. Claiborne Robins School

of Business, University of Richmond, Richmond, VA 23173. As is the case of the advertising and promotion campaign, the

Journal of Business Research 50, 297–303 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

focus of the study is on posthumous (or cadaveric) donation introducing significant bias when the telephone directory is an appropriate sampling frame for a study (Landon and Banks, rather than donation from living donors. Most donations,

especially between unknown or unrelated persons, are cadav- 1977). Usable responses were obtained from 161 persons in 1994, 126 in 1995, 142 in 1996, and 141 in 1997.

eric. (See the Appendix for an overview of the cadaveric organ procurement and allocation system in the United States.)

Measures

Attitude was measured using an 8-item, 5-point Likert type

Study Objectives

scale named the DONATT scale (see Table 1). The scale was It is believed that prior direct experience is a powerful contrib- developed following traditional scale development procedures (Churchill, 1979). The range of possible scale scores is 8–40, utor to attitude formation and reinforcement (Marks and

Kam-with higher scores indicating more positive attitudes. Coeffi-ins, 1988; Smith and Swinyard, 1983). In the case of organ

cientafor the scale across all four sample years is 0.83. Test-donation and transplantation, knowing an organ recipient,

retest reliability was measured on three convenience samples therefore, should have a positive influence on attitude toward

and ranges from 0.83 to 0.89. organ donation and transplantation.

Action was measured by asking participants if they had Also, there are several intermediate behaviors between

hav-executed an ODC. In addition, traditional demographic data ing a positive attitude toward organ donation and

transplanta-were collected. Finally, data on the prior direct experience tion and the ultimate behavior of organ donation. These

in-factor of knowing a transplant recipient and the intermediate clude such actions as donating blood and signing an organ

behavior factor of having donated blood were obtained. donor care (ODC). This last behavior indicates the intention

of performing the ultimate behavior of becoming an organ donor. It is commonly held that such a demonstrated

behav-Analyses and Findings

ioral intention is a more accurate predictor of actual future

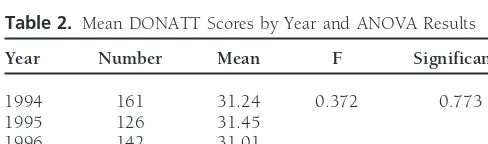

behavior than is attitude (Granbois and Summers, 1975; The four years of data were examined for variations in response Reibstein, 1978; Warshaw, 1980). to the DONATT scale using one-way ANOVA. The DONATT Therefore, the objectives of this study are to measure con- scores did not differ significantly over the course of the study current with the Ad Council/Coalition campaign: (p5 0.773) (see Table 2). That is, there is no evidence of any change in attitude toward donation over the years. Given 1. the changes in attitude toward organ donation and

the millions of dollars in media expenditures, one might have transplantation;

expected a positive change in attitude. While some might 2. the relationship to the prior direct experience of

know-suggest that the campaign was a failure, the absence of a ing an organ recipient; and

control group in this study makes measuring success or failure 3. the more proximate, intermediate behaviors of donating

impossible. It is possible that without the campaign, attitude blood and signing an ODC.

toward donation might have actually declined. It is also possi-ble that an already high positive response would reduce the chances of obtaining a significant gain in attitude.

Research Methods

A different perspective is gained from an examination of The study consists of four cross-sectional surveys conducted

the trend in the proportion of individuals reporting that they approximately one year apart in Richmond, Virginia. The first

had signed an ODC. The proportion reporting that they had survey was conducted in June 1994, just prior to the July

signed an ODC has increased significantly over the period of launch of the Ad Council/Coalition campaign, and was

re-the campaign (p,0.01) (see Table 3). While there has been peated in 1995, 1996, and 1997.

no change in the community’s attitude toward donation, there has been a significant increase in the percentage of respondents

Samples

who say that they have executed an ODC.Are actions matching words? It appears that they are. The A separate probability sample was selected for each survey.

The samples consisted of individuals at least 18 years of age proportion of each sample who had both agreed and strongly agreed with one statement in the DONATT scale: I would residing in the metro telephone calling area. Only persons

residing in households in which no one was employed in the donate my organs after my death and who had signed an ODC has shown a strong increase from 39% in 1994 to 63% healthcare industry are included in this study. Telephone

numbers were randomly selected from the telephone directory in 1997 (see Table 4).

To determine if these findings are the result only of sample (current at the time of each study). The11 sampling

tech-nique was employed so that new listings and unlisted numbers differences, the samples were compared along demographic and experience characteristics. Wheeler and Cheung (1996) could be accessed (Churchill, 1991). It has been shown to be

Table 1. DONATT Scale Itemsa

I would donate my organs after my death.b I find the idea of organ donation repulsive.

I would not allow the organs of a loved one to be donated. Organ transplantation is morally justified.b

Organ donation is against my religious beliefs.

If a family member signed a donor card, then I would approve the donation.b

I am worried that a loved one’s body would be disfigured if their organs were donated. People who receive organ transplants cannot live normal lives.

Cronbach’s coefficienta: all four sample years50.83; 1994, 0.83; 1995, 0.75; 1996, 0.88; 1997, 0.80.

Test-retest reliability was determined using the separate convenience samples of students: 18 undergraduates with 2-week measurement interval50.88; 61 undergraduates with 4-week measurement interval 50.83; and 15 MBA students with 4-week measurement inter-val50.89.

aStatement sequence rotated to control for order bias. bStrongly agree55.

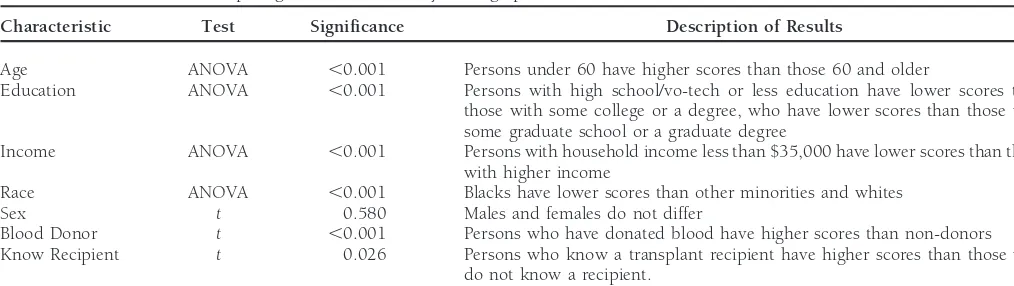

higher income persons are more likely to be organ donors. that a higher DONATT score indicates a more favorable atti-tude toward organ donation. There is no difference in DO-The Gallup survey (1993) found the likelihood to donate

increases significantly with education and nonwhites are less NATT by sex (p 5 0.58); but there is by age (p , 0.001), education (p , 0.001), income (p, 0.001, and race (p, likely than whites to want their organs donated. Non-Hispanic

whites tend to have both higher donation rates and more 0.001). The age groups split right at age 60, with those 60 and over having a lower score than those under 60. Higher favorable attitudes toward organ donation than do Blacks

and Hispanics. This exacerbates the general organ shortage educational levels are associated with higher DONATT scores. Persons with high school/vo-tech or less education have lower problem as some specific groups with a higher need for

trans-plants also have a lower donation rate (Farrell and Greiner, scores than those with some college or a degree while those who have some graduate school or a graduate degree have 1993). Wheeler and Cheung (1996) also found that single

Blacks and lower income Blacks are less willing to be donors higher scores than those with some college or an undergradu-ate degree. The income split occurs at $35,000. Those at or after death.

In some instances, notwithstanding how they feel about above $35,000 are more positive than those under $35,000. Whites and non-Black minorities have higher DONATT scores donation, some people simply believe they are too old or

cannot donate their organs due to medical reasons (Gallup, than Blacks. These findings conform with prior research (Wheeler and Cheung, 1996; Prottas, 1992).

1993). Having donated blood (Pessemier et al., 1977; Sanner,

1994a, 1994b) and knowing an organ transplant recipient are Those who personally know a transplant recipient are more favorable than those who do not (p50.026). Those who have also thought to be related to willingness to donate (Horton

and Horton, 1991). donated blood also have a more favorable attitude toward organ donation and transplantation than do those who have not The results of the analyses are mixed. While the groups

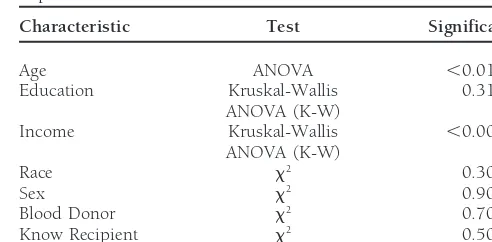

do not differ by sex (p5 0.90), by race (p5 0.30), or by (p,0.001). This also is confirmatory of prior research (Pessem-ier, 1977; Sanner, 1994a, 1994b; Horton and Horton, 1991). education (p50.31), they do differ significantly by age (p,

0.01) and by income (p,0.001). The samples do not differ The two characteristics that are significantly different both by sample year and by DONATT scores are age and income. in the proportion of respondents who have donated blood

(p 5 0.70) or who personally know a transplant recipient Those over 60 years of age were progressively less represented in the samples. The level of income also shows a slight decline (p5 0.50) (see Table 5).

Because the samples differ by age and income, DONATT over the years of the study. These changes in income and in age distribution would likely mitigate against each other in was tested against the same demographic and experiential

characteristics as were the sample groups (see Table 6). Recall

Table 3. Proportion of Participants Reporting That They Have/Have Not Signed an ODC by Year

Table 2. Mean DONATT Scores by Year and ANOVA Results

Signed an 1994 1995 1996 1997

Year Number Mean F Significance

ODC? (n5161) (n5126) (n5142) (n5141)

1994 161 31.24 0.372 0.773

Yes 28% 37% 50% 44%

1995 126 31.45

No 72% 63% 50% 56%

1996 142 31.01

1997 141 31.52

Table 5. Results of Tests Comparing Samples on Demographic and

Table 4. Proportion of Participants Who Strongly Agree or Agree

with the Statement “I would donate my organs after my death” and Experience Characteristics Who Report That They Have/Have Not Signed an ODC by Year

Characteristic Test Significance

Signed an 1994 1995 1996 1997

ODC? (n5109) (n586) (n599) (n591) Age ANOVA ,0.01

Education Kruskal-Wallis 0.31

ANOVA (K-W)

Yes 39% 54% 67% 63%

No 61% 46% 33% 37% Income Kruskal-Wallis ,0.001

ANOVA (K-W)

Race x2 0.30

x2significant at,0.01.

Sex x2 0.90

Blood Donor x2 0.70

Know Recipient x2 0.50

both attitude (DONATT scores) and behavior (a signed ODC). The change in age distribution should provide an upward bias and the change in income distribution should provide a

downward bias. donation and transplantation than persons who have never

The results of this study are mixed. DONATT scores are given blood. They have also displayed an intermediate behav-unchanged over the course of the four-year study but the ior—more than a positive attitude, less than a signed ODC. proportion of respondents who had signed an ODC had actu- The older segment of the population is also less inclined ally risen significantly over the years. Something had to be than the younger to favor organ donation. A cynical response at work to counteract the lack of enthusiasm for donation may be “So what?” because they are very poor potential donors. manifested by some members of the public. That “something” The fact is that the best cadaveric donors are young accidental may have been the Ad Council/Coalition campaign. While death victims. That response is, however, far too facile. The there are differences among various demographic segments older relative may be the one who has to make the decision in their attitudes toward donation, the reality is that there are to allow the recovery and transplantation of organs from a large numbers in all camps who have favorable attitudes. The deceased loved one. If not the parent of the deceased, the need is to capitalize on those favorable attitudes. older relative may be at least a strong personal influence on While this gratifying upturn in signed ODCs has been the relative who has to make the decision. Perhaps the Ad contemporaneous with the Ad Council/Coalition campaign, Council/Coalition might want to focus part of the campaign it cannot be totally ascribed to it. Also contemporaneous with on the scenario of offering sage advice in a trying moment. the campaign (perhaps due to the campaign) was news media While the attitude toward organ donation has remained attention concerning organ donation and transplantation. Such very stable over the course of the study (as shown by DONATT famous recipients as Larry Hagman, Mickey Mantle, and David scores), the action of signing an ODC has become more preva-Crosby, and such previously unknown donors as Nicholas lent. The lesson in this may be that the Ad Council/Coalition Green (the young American boy whose parents donated his is correct when they emphasize: “Share your life; Share your organs after he was killed by bandits in Italy) were in the decision.” In other words, it is not enough to think positive, news. This news should have helped galvanize public attention one must act positive. This is definitely an example of shaping to the issue of organ recovery and donation. Parsing these behavior in a market for a high-involvement decision. effects is obviously difficult, but there can be little doubt the

campaign was a major factor.

Limitations

Although probability samples were employed in every phase

Management Implications

of the study, the study was limited to the metro area of Rich-This study indicates that the organ procurement and trans- mond, Virginia. This is the headquarters of UNOS, so there plantation community must continue in its quest to under- might have been an initial higher awareness of donation and transplantation. There is, however, no direct evidence of this. stand what motivates individuals to become—or not to

be-come—organ donors and to employ sophisticated marketing Projecting the findings beyond this area may be inappropriate. Also, although the upturn in signed ODCs has been con-techniques to encourage donation. Special emphasis must be

placed on the Black community in particular. While Blacks temporaneous with the Ad Council/Coalition campaign, it should not be totally ascribed to it. As noted, several newswor-continue to demonstrate disproportionate need, they generally

exhibit a less positive attitude toward donation and trans- thy events transpired which may have had an impact on the public’s perception of donation and transplantation. These plantation than do whites.

One approach to gaining insights about motivations may events must also be allowed as having had an impact— whether positive or negative.

be to study blood donors. They are a readily identifiable

Table 6. Results of Tests Comparing DONATT Scores by Demographic and Other Characteristics

Characteristic Test Significance Description of Results

Age ANOVA ,0.001 Persons under 60 have higher scores than those 60 and older

Education ANOVA ,0.001 Persons with high school/vo-tech or less education have lower scores than

those with some college or a degree, who have lower scores than those with some graduate school or a graduate degree

Income ANOVA ,0.001 Persons with household income less than $35,000 have lower scores than those

with higher income

Race ANOVA ,0.001 Blacks have lower scores than other minorities and whites

Sex t 0.580 Males and females do not differ

Blood Donor t ,0.001 Persons who have donated blood have higher scores than non-donors

Know Recipient t 0.026 Persons who know a transplant recipient have higher scores than those who

do not know a recipient.

Groupings used for analysis: Age,30, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59,.59; Education: high school/vo-tech or less, some college, college degree, some graduate school or graduate degree; Income:,$35K, $35K–$64.9K, $65K–$95K,.$95K; Race: Black, other minority, white; Blood Donor: have donated, have not donated; Know Recipient: know an organ transplant recipient, do not know an organ transplant recipient.

Note: Duncan’s multiple range test (a 50.05) was used in conjunction with ANOVA to test for differences between groups.

whether a respondent had signed an ODC—was a self-report of a minor. SOBRA states that when there is no ODC, physi-and cannot be verified. Further, no attempt was made to cians and hospitals are required to present organ donation as determine if social desirability, or “yea-saying,” was at play in an option to the families of patients judged to be dying or participants’ responses. who have just died. This is referred to as required request

(Farrell and Greiner, 1993).

The actual recovery and distribution is conducted by

not-Appendix

for-profit organ procurement organizations (OPOs) (Alexan-der et al., 1992). All OPOs and transplant hospitals are

re-Cadaveric Organ Procurement and

quired by law to be OPTN members. Currently there are 54

Allocation in the United States

independent and 12 transplant-center-affiliated OPOs in theUnited States. Upon notification by a hospital of a potential The National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) of 1984 (as

donor, OPO staff contact the families of potential donors to amended in 1988 and in 1990), the Uniform Anatomical

discuss the donation option, and if permission to recover Gift Act (UAGA), and the Sixth Omnibus Budget

Reconcilia-organs is granted, they enter necessary donor data into the tion Act (SOBRA) provide the legal framework for organ

United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) computer system. donation in the United States. NOTA specifically outlawed

UNOS is a private, non-profit organization that holds federal the buying or selling of human organs and tissue and

estab-contracts to operate the OPTN and to maintain the U.S. Scien-lished the National Organ Procurement and Transplantation

tific Registry of Transplant Recipients. UNOS has specific Network (OPTN) (Prottas, 1993; UNOS, 1997). Note that

policies regarding standards of membership, organ allocation, the use of financial incentives has been suggested by some

and data management. At this time the policies and standards as a means of increasing donations. For further information,

are not enforceable by law and are considered voluntary guid-see Altshuler and Evanisko (1992), Barnett et al. (1992),

ance to OPTN members (UNOS, 1997). Cosse´ and Weisenberger (1997), and Kittur et al.(1991).

UNOS provides the OPO with a priority listing of potential The UAGA explicitly authorized the voluntary gifting of

recipients. The first list generated is usually limited to patients body parts upon death and delineates a hierarchy of rules

in the OPO’s service area. If a suitable recipient is not found governing how the gift may be stipulated and who may

on that list, a regional list is generated, and finally a nationwide commit the gift. The U.S. organ donation process is based on

list is obtained. The OPO then contacts the OPOs in the explicit consent. Under explicit consent, individuals (adults)

areas where potential recipients are located. The donor’s OPO decide if they wish to become organ donors. Typically

com-maintains the donor and coordinates organ recovery, preserva-mitment to be a donor is made by signing an organ donor

tion, and transportation. The recipients’ OPOs (one donor’s card (ODC)—which may be one’s state driver’s permit. By

organs may go to a number of different recipients) arrange law an individual’s wish to be a donor, as demonstrated by

the transplant activities—line up the transplant teams and an executed ODC, is a binding authorization to remove the

prepare the recipients for surgery. UNOS assists the recovery person’s organs after death regardless of the wishes of the

and transplantation teams with organ matching and transpor-individual’s family. In the absence of an ODC, the UAGA

tation (Benenson, 1991) and oversees the process to ensure specifies which family members have a right to authorize a

and Ethical Components of Organ Donation.Nebraska Medical

In April 1998, the Department of Health and Human

Ser-Journal(October 1993): 324–330. vices published the OPTN Rule requiring standardized criteria

Gallup Organization:The American Public’s Attitude Toward Organ

for listing patients on the waiting lists and for determining

Donation and Transplantation: A Gallup Survey for The Partnership

medical status (HHS 1998a). In addition, the rule eliminates for Organ Donation(February 1993). the current practice of first searching for recipients within the

Granbois, Donald, and Summers, John O.: Primary and Secondary recovering OPO’s service area. Further, it requires a nation- Validity of Consumer Purchase Probabilities.Journal of Consumer wide search to find the person most in need of an organ(s). Research(March 1975): 31–38.

The rule was set go into effect in July 1998 (see HHS, 1998b). Horton, Raymond L., and Horton, Patricia J.: A Model of Willingness However, considerable opposition was expressed by members to Become a Potential Organ Donor.Social Science Medicine33,

9 (1991): 1048. of the procurement and transplantation community. In

Octo-HHS: HHS Rule Calls for Organ Allocation Based on Medical Criteria, ber 1998, the 1999 Omnibus Appropriations Act was passed.

Not Geography.HHS News Release. U.S. Department of Health The act places a one-year moratorium on the OPTN Rule.

and Human Services. (March 26, 1998a). During that year the act requires review of the OPTN policies

HHS: Improving Fairness and Effectiveness in Allocating Organs and a number of studies dealing with the impact of the OPTN

for Transplantation. HRSA News: Fact Sheet. U.S. Department Rule on procurement and transplantation. Refer to the UNOS of Health and Human Services. Health Resources and Services homepage at www.unos.org and the Health Resources and Administration. (March 26, 1998b).

Services Administration homepage at www.hrsa.dhhs.gov for Kaufmann, Ralf, Nix, Christoph, Klein, Martin, Reul, Helmut, and regular updates on this issue (UNOS, 1998b). Rau, Gu¨nter: The Implantable Fuzzy Controlled Helmholtz-Left Ventricular Assist Device: First in Vitro Testing.Artificial Organs 21, 2 (1997): 131–137.

For this article, the authors received the 1998 Steven J. Shaw Award for the

Best Conference Paper at the Annual Conference of the Society for Marketing Kittur, Dilip S., Hogan, M. Michele, Thukral, Vinod K., McGaw,

Advances. Lin Johnson, and Alexander, J. Wesley: Incentives for Organ Donation?Lancet338 (December 1991): 1442.

Landon, E. Laird Jr., and Banks, Sharon K.: Relative Efficiency and

References

Bias of Plus-One Telephone Sampling.Journal of MarketingRe-search14 (August 1977): 294–299. Alexander, J. Wesley, Broznick, Brian, Ferguson, Ronald, Haid,

Ste-phen, Kirkman, Robert, Melzer, Juliet, and Phillips, Michael: Or- Marks, Lawrence J., and Kamins, Michael A.: The Use of Product gan Procurement Organization Function.UNOS Update(Septem- Sampling and Advertising: Effects of Sequence of Exposure and

ber, 22-25, 1992). Degree of Advertising Claim Exaggeration on Consumers’ Belief

Strength, Belief Confidence, and Attitudes.Journal of Marketing Altshuler, Jill. S., and Evanisko, Michael J.: Financial Incentives for

Research25 (August 1988): 266–281. Organ Donation: The Perspectives of Health Care Professionals.

Journal of the American Medical Association 267 (April 1992): Nathan, Howard: Phase III Campaign for Organ and Tissue Donation.

2037–2038. Coalition on Donation Memorandum to OPO Executive Directors

(November 24, 1997). Arundell, M. A., and McKenzie, I. F. C.: The Acceptability of Pig

Pessemier, Edgar A., Bemmaor, Albert C., and Hanssens, Dominique Organ Xenografts to Patients Awaiting a Transplant.

Xenotrans-M.: Willingness to Supply Human Body Parts: Some Empirical plantation4 (1997): 62–66.

Findings.Journal of Consumer Research4 (December 1977): 131– Barnett, Andrew H., Blair, Roger D., and Kaserman, David L.:

Improv-140. ing Organ Donation: Compensation Versus Markets.Inquiry29

Prottas, Jeffrey M.: Altruism, Motivation, and Allocation: Giving and (Fall 1992): 372–378.

Using Human Organs.Journal of Social Issues49 (Summer 1993): Basu-Dutt, Sharmistha, Fandino, Mary R., Salley, Steven O., Thomp- 137–150.

son, Ian M., Whittlesey, Grant C., and Klein, Michael D.:

Feasibil-Prottas, Jeffrey M.: Competition for Altruism: Bone and Organ Pro-ity of a Photosynthetic Artificial Lung.ASAIO Journal21, 2 (1997):

curement in the United Sates.The Millbank Quarterly70 (Summer 279–283.

1992): 299. Benenson, Esther L.: UNOS: Evolution of the Organ Procurement

Reibstein, David J.: The Prediction of Individual Probabilities of and Transplantation Network.Dialysis & Transplantation20, 8

Brand Choice.Journal of Consumer Research5 (December 1978): (1991): 495–496.

163–168. Churchill, Gilbert A. Jr.:Marketing Research: Methodological

Founda-Sanner, Margareta: Attitudes Toward Organ Donation and Trans-tions, 5th ed., Dryden Press, Hinsdale, IL. 1991.

plantation: A Model for Understanding Reactions to Medical Pro-Churchill, Gilbert A. Jr.: A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures cedures After Death.Social Science & Medicine38 (August 1994a):

of Marketing Constructs.Journal of Marketing Research16 (Febru- 1141–1152.

ary 1979): 64–73. Sanner, Margareta: A Comparison of Public Attitudes Toward

Au-Cosse´, Thomas J., and Weisenberger, Terry M.: Perspectives of the topsy, Organ Donation, and Anatomical Dissection: A Swedish Use of Financial Incentives for Human Organ Donation, inMar- Survey.Journal of the American Medical Association271 (January keting: Innovative Diversity. Proceedings Atlantic Marketing Associa- 1994b): 284–288.

tion 1997 Annual Conference. Jerry W. Wilson, ed., Nashville, TN. Smith, Robert E., and Swinyard, William R.: Attitude-Behavior

Con-1997, pp. 89–100. sistency: The Impact of Product Trial Versus Advertising.Journal

UNOS:1996 Annual Report: The U.S. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients and The Organ Procurement Transplantation Network. Recipients and The Organ Procurement Transplantation Network, UNOS and Health Resources & Services Administration. U.S. UNOS and Health Resources & Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 1998b.

Department of Health & Human Services, 1997. Warshaw, Paul R.: Predicting Purchase and Other Behaviors from UNOS: http://www.unos.org (January 21, 1998a). General and Contextually Specific Intentions.Journal of Marketing

Research17 (February 1980): 26–33. UNOS: http://www.unos.org/Newsroom/archive regs update

102-199.htm(1998b). Wheeler, Mary S., and Cheung, Alan H. S.: Minority Attitudes Toward