www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Strain differences in aggressiveness of male

domestic fowl in response to a male model

Suzanne T. Millman

1, Ian J.H. Duncan

)Department of Animal and Poultry Science, UniÕersity of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1

Accepted 30 August 1999

Abstract

The objective of this experiment was to determine if the unusually high levels of aggression shown by male broiler breeder domestic fowl towards females is due to a higher overall level of

Ž . aggressiveness in this strain. We compared the aggressive behaviour of broiler breeder BR males

Ž .

with that of males of an Old English Game strain GA which had been bred for fighting. Also, by Ž .

rearing males of a commercial laying strain LR under the same level of feed restriction

recommended for broiler breeder males, we examined the effects of feed restriction during rearing Ž .

on aggressive behaviour at maturity. Full-fed commercial laying strain LA males were used as a control. The behaviour of individual males, nine from each treatment group, towards a model of a male conspecific was recorded for 15 min. The test was repeated 4 weeks later, after the males had received some limited sexual experience. Game strain males reacted most aggressively to the

Ž . Ž .

model, waltzing P-0.001 and crowing P-0.05 more than males from the other treatment

groups which did not differ significantly from each other. Waltzing and crowing also increased

Ž .

significantly from the first to the second test in GA males P-0.005 , but not in males from the other treatment groups. Frequency and duration of ground pecking was significantly less in BR

Ž .

males than in GA or LA males P-0.005 and significantly less in GA and LA males than in LR

Ž .

males P-0.05 . Frequency of wing flapping was significantly greater in BR and LR males than

Ž .

in GA or LA males P-0.005 . In conclusion, broiler breeder males did not behave aggressively towards a male model relative to game strain males. Whereas feed restriction during the rearing phase did affect behaviour of adult males, aggressiveness towards a male model did not increase. q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Aggression; Genetics; Feed restriction; Chickens

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q1-519-824-4120; fax:q1-519-836-9873; e-mail: [email protected] 1

Current address: Farm Animals and Sustainable Agriculture Section, Humane Society of the United States, 2100 L St. NW, 20037 Washington, DC, USA.

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Ž .

1. Introduction

This experiment was conducted as one of a series of experiments investigating problems of aggression towards females by broiler breeder males. High levels of

Ž

aggression directed toward females by male broiler breeder domestic fowl Gallus gallus

.

domesticus have been reported in the poultry industry during the past 5–10 years ŽMench, 1993; Dr. Rachel Ouckama, personal communication . Males are extremely.

rough during mating, forcing copulations and often injuring or killing females. Initially, problems were reported in one particular male strain, but now appear to be associated with all North American commercial strains of broiler breeders. In flocks in which aggression has become a problem, males typically chase and ‘‘corral’’ females into corners. Females avoid males by running away, by hiding in nest boxes and by remaining on raised slatted areas. Females typically have lacerations on the back of the head caused by males pecking and along the torso, underneath the wings caused by males’ claws when they mount roughly. There have been reports of attacks by males on employees in broiler breeder barns and this phenomenon may resemble the mobbing behaviour toward humans handling birds in large breeding flocks observed by Curtis

Ž1986 . Male aggression has a deleterious economic effect on the poultry industry.

through decreasing fertility and increasing female mortality. The injuries and the fear caused to the females also raise serious concerns for animal welfare.

This phenomenon of male aggression towards females is interesting from a theoreti-cal as well as a practitheoreti-cal point of view. Whereas immature males may behave

Ž .

aggressively to females Wood-Gush, 1960; Rushen, 1983 , such aggression by mature

Ž

male domestic fowl is rare Wood-Gush, 1960; Kruijt, 1964; Craig and Bhagwat, 1974;

.

Ylander and Craig, 1980; Bsary and Lamprecht, 1994 . Males and females form separate

Ž .

social hierarchies and males dominate females passively Guhl, 1949 . Furthermore, selection for growth has been found to be associated with decreased aggression

ŽMarsteller et al., 1980 , while selection for egg production and low body weight may be.

Ž .

associated with increased agonistic activity Craig et al., 1975 . Our previous research indicated that broiler breeder males showed more aggression to males than did commer-cial laying strain males and more unusually, they chased and aggressively pecked

Ž .

females much more frequently Millman et al., 1997 . Broiler breeder males also showed lower frequencies of courtship displays and forced more copulations when compared

Ž .

with commercial laying strain males Millman et al., 1996 . Courtship displays may

Ž

arise from conflicting sexual, attack and escape motivations Wood-Gush, 1956; Kruijt,

.

1.1. Management practices

Due to the growth potential of broiler stock, broiler breeders must be reared under severe feed restriction to prevent obesity and problems associated with rapid growth

ŽLeeson and Summers, 1991 . During the rearing period, feed allocation is 40–50% of.

ad libitum intake resulting in body weights at 22 weeks which are 65% of that of ad

Ž .

libitum fed birds North and Bell, 1990 . Such severe feed restriction results in

Ž .

stereotypic pecking suggestive of high levels of frustration Savory and Maros, 1993 . Moreover, frustration associated with thwarting of feeding behaviour has been shown to

Ž .

increase aggression toward females by males Duncan and Wood-Gush, 1971 . Mench

Ž1988 found that although broiler chicks displayed low levels of aggression when.

compared to laying stock, feed-restricted 12-week-old broilers showed significantly more threats and pecks than did those fed ad libitum. Since much of the aggression appeared at the feeder, she concluded that frustration was a factor. Conversely, our research indicated that aggression was higher in males that were full-fed at maturity

ŽMillman et al., 1997 . However, all of our broiler breeder males were feed-restricted.

during the rearing period to avoid obesity and it is possible that feed restriction during the rearing phase affects aggression at maturity. Effects of the social environment during

Ž

rearing have been shown to affect sexual behaviour of females at maturity Leonard et

.

al., 1993b; Widowski et al., 1998 and aggressive and sexual behaviour of mature males

ŽLeonard et al., 1993a . Feed restriction is imposed at 1–3 weeks of age in broiler.

Ž .

breeder management Ross Breeders, 1997 which coincides with development of social

Ž .

behaviour in chicks Kruijt, 1964 .

1.2. Genetic selection

Broiler chickens have been heavily selected for meat production and reach market

Ž .

weight at 42 days of age North and Bell, 1990 . At this age, broilers have been found to

Ž .

be less aggressive than laying strain males Mench, 1988 . However, it is possible that aggression in broilers does not increase until sexual maturity and hence is only observed in the breeder stock. In attempts to increase breast meat yield, the Cornish strain,

Ž

traditionally used for cock-fighting, has been bred into the male line North and Bell,

.

1990 and it is possible that this has resulted in an increase in aggressiveness.

Also, aggression may have been inadvertently selected through attempts to improve sexual vigour. There persists a belief in the broiler breeder industry that male lines need

Ž

to be more sexually aggressive to overcome problems of low fertility Peterson

.

Breeders, personal communication . Selection for high and low mating lines was

Ž . Ž .

successfully performed by Wood-Gush 1960 using laying stock and by Siegel 1972 using broiler stock. Although a genetic basis for aggressiveness was also found by

Ž . Ž

Siegel 1959 , no relationship was found between aggressiveness and sex drive

Wood-.

Gush, 1958; Siegel, 1972 . Low fertility in broiler breeders was shown to result from

Ž .

lack of cloacal contact and not from low levels of libido in males Duncan et al., 1990 .

Ž .

This experiment was designed to investigate how feed restriction during rearing and genetic strain affect the aggressiveness of male domestic fowl at sexual maturity. We used commercial laying strain males to examine the effects of feed restriction during rearing and thus avoided the confounding effects of obesity in full-fed broiler breeder males. Behaviour of laying strain males fed ad libitum during rearing was compared with that of males feed-restricted to the same degree as in broiler breeder production. Behaviour of broiler breeder males was compared with that of Old English Game males, a strain traditionally bred for its fighting behaviour. Since commercial laying strain males had shown low levels of aggression to females in our previous research they were used as controls. Our hypothesis was that feed-restricted laying strain males would show higher levels of aggression than males fed ad libitum during rearing. We also expected that broiler breeder males would show levels of aggression similar to that of Old English Game strain males and much higher than that of commercial laying strain males. Aggressiveness was determined using a standardised test in which we recorded re-sponses to a model of a cockerel in a standing, non-threatening posture.

2. Animals, materials and methods

Sexually mature males were observed in each of four treatments. Treatments con-sisted of broiler breeder males which had been reared and maintained with feed

Ž .

restricted according to the management guidelines BR , commercial laying strain males

Ž .

which had been reared and maintained with feed provided ad libitum LA , commercial

Ž .

laying strain males which had been reared and maintained with feed restricted LR and

Ž .

Old English Game males reared and maintained with feed provided ad libitum GA . Twenty-four Ross broiler breeder males and 48 ISA Brown commercial laying strain males were purchased from local hatcheries as day-old chicks and were housed at the OMAFRA Arkell Poultry Research Station. All chicks were vaccinated for the standard local diseases and were neither dubbed nor toe trimmed. Commercial laying strain males were randomly assigned to either full-fed or restricted treatments. Males were reared in 3.35 m=3.65 m pens, with pine shavings as litter. At 1 week of age chicks were wing-banded for identification and beak-trimmed to prevent feather pecking. Lighting

Ž .

regime followed recommendations for broiler breeder stock Ross Breeders, 1997 with 8 h of light until 21 weeks of age and gradually increased thereafter to 16 h of light

Ž05:00–21:00 at 25 weeks of age. The BR males were feed-restricted according to the.

Ž .

management guideline for that strain Ross Breeders, 1997 . The LA males were fed ad libitum throughout the experiment. Feed restriction of LR males was such that their body weight was maintained at the same percentage of full-fed body weight as with

Ž .

broiler breeders of equivalent age North and Bell, 1990 . All males were weighed weekly during rearing and were fed a standard mash grower diet daily.

room of the same building. All pens had wire mesh walls and pine shavings on the floor. All males had visual access to neighbouring males.

Ž .

Nine Old English Game males Pine Albany strain were obtained on loan from a local breeder. While cock-fighting is illegal in Canada, it is still legal in some states in the USA. The parental stock of these birds were imported for show purposes from New York State and the breeder confirmed that the males loaned for use in these experiments were one generation removed from fighting or ‘‘pit’’ stock. All birds were hatched and brooded by an Old English Game female and reared out of doors in a group of mixed age and sex. Prior to sexual maturity males were individually penned with visual access, but no physical access to other males. All Game fowl were obtained at approximately 28 weeks of age. Birds were neither beak-trimmed, toe-trimmed nor dubbed. Since GA males had been individually housed prior to sexual maturity, they were sexually inexperienced, but had received social experience when immature with mature and immature females.

Due to concern for disease transmission GA males were housed at the OMAFRA Isolation Unit of the University of Guelph. Males were individually housed in 1.22 m=1.22 m pens with pine shavings on the floor and a perch located 0.61 m above the floor. Because these males were extremely aggressive, pens were solid sided to prevent fighting and threatening between neighbouring males. Males could see other males through the barred pen door, but could not reach them to fight. At the request of the breeder, all GA males were fed ad libitum a mixture of standard breeder mash, pigeon seed, scratch grains and fresh fruit. Despite the flighty nature of these birds, they had been handled frequently and seldom showed aggression to people. However, certain males were extremely aggressive and had to be handled with care.

Males of all strains were approximately 31 weeks of age when testing began. Our aggression test consisted of recording responses of the males to a model of a male conspecific. Aggression in domestic fowl has been found to be more common between

Ž .

individuals which are similar in appearance Lill, 1968 . A Barred Rock male was chosen for our model as its mottled black and white plumage was markedly different from that of the three male strains tested and hence would affect males equally. The individual Barred Rock male used as the model weighed approximately 3.5 kg, whereas the average weights of BR, LR LA and GA males were 5.4, 2.3, 2.8 and 2.1 kg, respectively, when the experiment concluded at 39 weeks of age. A relaxed and non-threatening pose was chosen in the belief that a threatening Barred Rock male may look more intimidating to the smaller GA, LA or LR strain males than to the large BR males. Also, motivation of males to initiate rather than respond to aggression was of particular interest, as females rarely initiate aggression with males.

The model was developed by suspending a euthanised Barred Rock male in a sling attached to two dowling rods. He was then essentially made into a marionette or puppet by arranging his appendages and head using strings. As this was accomplished prior to rigor mortis, the posture of the bird was easily manipulated such that his head was elevated, beak held level and wings lay close to his body. His eyes were left closed for fear that freezing might affect the structure of the eyeball, making the model less convincing. In addition, one would expect a bird with its eyes closed to be perceived as

Ž .

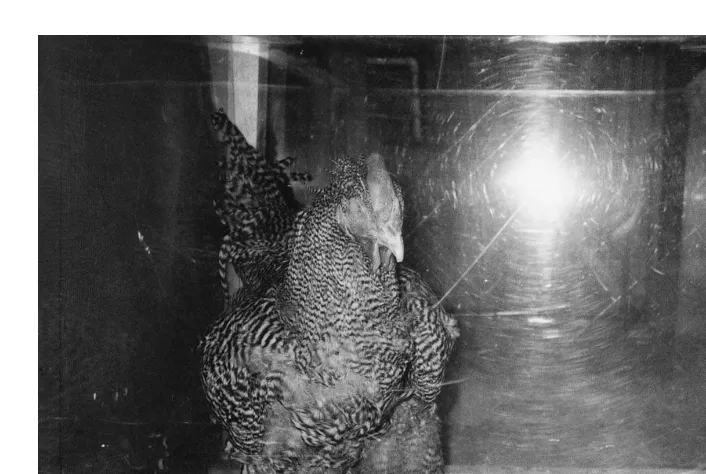

Fig. 1. Frontal view of frozen Barred Rock male model in the Plexiglas box.

freezer for 24 h, the sling and strings were removed and the model was stored in a large plastic bag in the freezer.

When the model was removed from the freezer for approximately 1.5–2.0 h during testing, minimal damage was observed as a result of thawing, likely due to the insulating value of feathers. When first removed from the freezer some frosting up of the comb and wattles was observed. Testing was not initiated until 5–10 min after the model was removed from the freezer, by which time these appendages thawed enough to appear reddish-pink and life-like. The model was placed in a 0.6 m=0.6 m Plexiglas box as protection from physical contact with the males during the test.

Testing was performed in a separate room in the same building in which the birds

Ž .

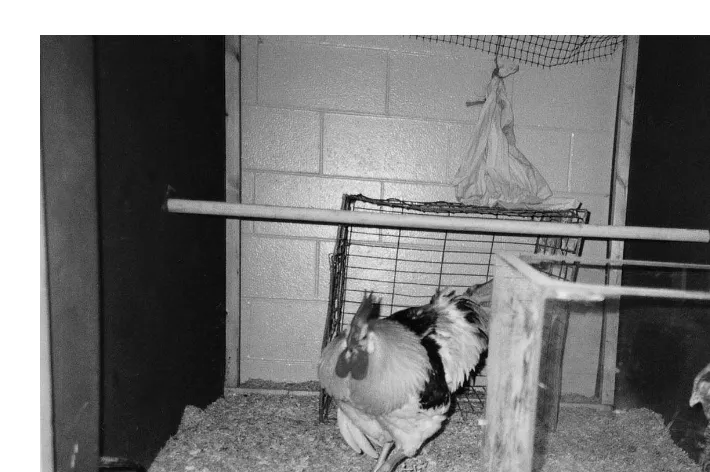

Fig. 2. The arrangement of the test pen. The cotton sheet has been raised, allowing the test male to see and approach the model.

Testing procedure involved carrying a male in an upright position from his home pen to the wire cage. As males were accustomed to being handled, they appeared relaxed and displayed little fear as a result of being carried. In fact, some individuals crowed or gave food calls while being carried to the test room during the second round of testing. Visual access to the model was obstructed while the male was placed in the wire cage and the cotton sheet placed across the open cage front. After allowing the male to acclimatise to the cage for 1 min, the cotton sheet was removed. The male was then able to interact with the model through the Plexiglas. Behaviour was video-recorded for 15 min, after which the male was caught and returned to his home pen.

Males were tested individually. No other birds were in the test room, however some auditory contact with other birds in the building existed. Three birds were tested every second evening between 17:00 and 18:00, with males from the same treatment tested during the same week. This time was chosen because it is known that sexual behaviour

Ž .

in domestic fowl increases later in the day Lake and Wood-Gush, 1956 . Each male was tested once and then tested again 4 weeks later. Since the first test was followed immediately by another experiment in which males were placed with three females for

Ž .

26 h Millman and Duncan, unpublished data , males were sexually inexperienced during the first aggression test, but had received limited sexual experience 4 weeks prior to the second aggression test.

Ž

Videotapes were analysed using the Observer software program Noldus Information

.

Ž .

Descriptions of behavioural elements were in accordance with Wood-Gush 1956 . Frequencies of the following behavioural elements were recorded over 15 min — threats, waltzes, crows, wing flaps and ground pecks. Durations of time spent ground pecking and in an alert posture were also recorded.

Since some males did not perform some behavioural elements, the data set contained a large number of zero values, skewing the distribution from normality. Logarithmic transformation improved the normality of the data; however as zero values tended to be concentrated in certain treatments, variance was not homogeneous. For this reason, non-parametric statistical analysis was felt to be more appropriate and was performed using SAS NPAR1WAY procedure on mean frequencies and differences in frequencies

Ž .

between the first and second aggression test SAS Institute, 1985 . The Kruskal–Wallis test on Wilcoxon scores of ranked sums was used to determine if there was a significant

Ž .

difference between treatments. A Tukey-like test for multiple comparisons Zar, 1984 was used to determine which of these treatments differed.

During the rearing phase males were housed together, with one pen per treatment. One could argue this resulted in one replication of each treatment. However, housing males individually at such an early stage of development would have radically affected their social behaviour at maturity and would have masked any differences resulting from

Ž .

feed restriction during rearing. Also, we wished our research to have relevance to commercial conditions where birds are reared in very large group sizes and further reducing group size in our experiment would have reduced the application of our results. Feed-restricted birds display extreme aggression and mobbing at the feeder during feeding, which could affect social behaviour at maturity. We reared twice the number of birds required for behavioural observation, in an attempt to maximise group size during rearing. Ideally, we would have reared nine pens of males per treatment from which one male would be tested, but this was not possible due to space limitations at the research facility and concerns of the number of animals used for this research. As males were individually housed at sexual maturity and observations did not commence for another 10 weeks we felt justified in treating the nine males within each treatment as replications and not an experimental unit.

3. Results

Feed restriction of laying strain males during the rearing phase was successfully accomplished without causing undue hardship. Feed restriction as practised in the broiler

Ž .

breeder industry is severe and results in stereotypic pecking, increased drinking and

Ž .

increased activity suggestive of frustration and suffering see Section 1 . Casual observation during the rearing phase indicated such behaviour was performed by both broiler breeder and by feed-restricted laying strain males. Broiler breeder males also behaved aggressively during the rearing phase, often chasing and pecking each other. Aggression was not as pronounced in feed-restricted laying strain males, which may indicate differences in severity of feed restriction or strain differences in responses to feed restriction. However, only casual observations were taken at this time. Feed restriction delays maturity and laying strain males developed secondary sexual character-istics and crowed at a later age than males fed ad libitum. Body weight continues to

Ž

increase during the breeding phase in feed-restricted broiler breeder males Ross

.

Breeders, 1997 , but body weight of ad libitum fed males reaches a maximum and levels off at an earlier age. Hence, the percentage of ad libitum body weight attained by

Ž

feed-restricted males increases as the birds age. In our previous research Millman et al.,

.

1996, 1997 , we found feed-restricted broiler breeder males were 80% of the body weight of ad libitum fed males at 37 weeks of age. Similarly, in the current experiment feed-restricted laying strain males were 82% of the body weight of males fed ad libitum.

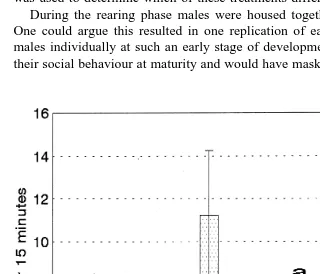

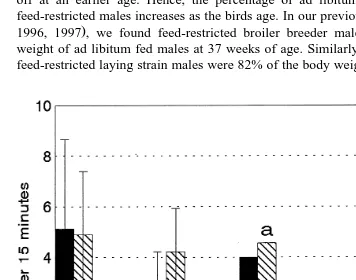

Fig. 5. Frequencies of wing flapping displayed during tests 1 and 2. Mean frequencies of wing flapping

Ž"S.E. and difference in frequencies of wing flapping between the two tests were statistically significant.

As expected, Game males were the most aggressive. Whereas threats occurred at very low frequencies and were not found to differ significantly between treatments, Game

Ž

males waltzed more than 10 times as frequently as did males of other strains Fig. 3,

. Ž

P-0.001 . Crowing also was performed significantly more by Game males Fig. 4,

.

P-0.05 . Both crowing and waltzing were found to increase significantly in Game

Ž .

males during the second test P-0.005 and P-0.05, respectively . One Game male attempted a flying attack on the model through the Plexiglas and casual observation of Game males indicated they were also considerably more aggressive in their home pens. Males attempted to fight with each other through the solid walls of their pens despite visual restriction and some males behaved aggressively to human handlers, which was never observed in males of the other treatments.

Wing flapping occurred at much lower frequencies than did crowing or waltzing and

Ž .

was rarely observed in full-fed males Fig. 5 . Wing flapping was highly variable among individuals. Feed-restricted laying strain males showed significantly more wing flapping

Ž .

than did full-fed laying strain and Game males P-0.005 and wing flapping by broiler breeder males approached being significantly greater than that shown by full-fed laying strain and Game males. Frequency of wing flapping did not change significantly over the two tests for any of the treatments.

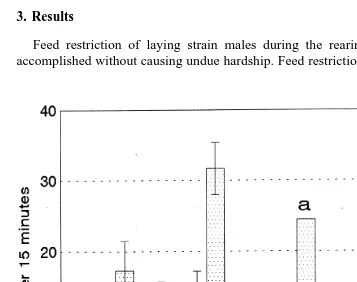

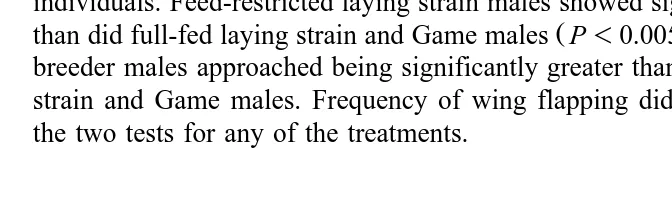

Fig. 6. Frequencies of ground pecking displayed during tests 1 and 2. Mean frequencies of ground pecking

Ž"S.E. and difference in frequencies of ground pecking between the two tests were statistically significant.

Ž

Feed-restricted laying strain males performed the most ground pecking Fig. 6,

.

P-0.05 suggesting that they too were affected by conflicting motivations. Since broiler breeder males showed the lowest levels of ground pecking in both frequency and duration, this display cannot be accounted for simply as foraging due to feed restriction. Game and full-fed laying strain males were intermediate in frequency and duration of ground pecking and for both of these treatments, ground pecking significantly increased

Ž .

during the second test P-0.01 . Although auditory signals were not recorded, casual observation indicated that feed-restricted laying strain, full-fed laying strain and Game males tended to give food calls when they were being carried to the pen in the second test. It is possible that males, due to their prior experience with females in the test pens 4 weeks earlier, were anticipating contact with females. However, this does not explain why feed-restricted laying strain males ground pecked at high levels during the first test. Alert behaviour was highly variable among individuals and was not found to differ significantly between treatments. Broiler breeder males did not show high levels of alert behaviour. Clearly, the low level of aggressive behaviour by broiler breeder males was not a result of overriding fearfulness in males of this strain. Game males showed a significant increase in alert behaviour during the second test when compared with

Ž .

full-fed laying strain males P-0.001 . Interestingly, although Game males appeared to be more alert in the second test, they also displayed more waltzing and crowing. This suggests that either aggressive motivation in Game males was high enough to override their fearfulness or that the alert response may have been more indicative of arousal than fearfulness.

4. Discussion

In this experiment a frozen male was used as a model to elicit aggressive responses by male domestic fowl. As males oriented themselves towards, reacted aggressively towards and even attempted to attack the model through the Plexiglas, we conclude that this approach was effective as a test of aggressiveness. This method of producing models had the advantage of being time efficient and considerably less expensive than using a stuffed model requiring skills of a taxidermist. Assuming freezer space is available, frozen models could be stored for long periods of time with no risk of damage due to moths or mould. Provided that the model was positioned prior to rigor mortis, posture was easily manipulated and was maintained through the freezing process. Comb and wattle colour were not noticeably affected by freezing during the 8 weeks of this experiment, although frosting up occurred immediately on removal from the freezer, but disappeared within 10–15 min at room temperature. Maintaining the frozen model at room temperature for 1.0–1.5 h did not noticeably alter the appearance of the bird, likely due to the insulating value of feathers.

Ž

pecking suggestive of a greater state of conflict Kruijt, 1964; Duncan, 1970; Feekes,

.

1971 . Since wing flapping occurs in a variety of contexts, it is not clear whether

Ž .

conflicting motivations in this situation related to aggressive tendencies. Duncan 1970 found wing flapping to increase in Brown Leghorn males when presented with a caged rather than uncaged female. He suggested wing flapping increased as a result of frustration due to prevention of sexual contact. It is possible in our experiment that hunger and frustrated feeding motivation associated with severe feed restriction resulted in greater conflict in the test situation. However, as threats and waltzes were rarely performed by feed-restricted laying strain males it is unlikely that increased conflict caused or was a result of increased aggressiveness. Ground pecking by full-fed laying strain and Game males increased during the second test to levels equivalent to that of feed-restricted laying strain males. It is possible that sexual experience in the test pens 4 weeks prior to the second test resulted in sexual motivation being superimposed on attack and escape motivation in response to the model. The addition of sexual motiva-tion may have pushed full-fed laying strain and Game males to the same high, perhaps maximal, level of conflict as experienced by feed-restricted laying strain males, resulting in increased ground pecking. However, wing flapping was not seen to increase in full-fed laying strain and Game males during the second test. Also, broiler breeder males, despite being feed-restricted, did not differ significantly from other males in frequency of wing flapping and rarely performed ground pecking. A study by Hocking

Ž .

et al. 1997 found that full-fed 11-week-old laying strain males displayed more pacing and preening than full-fed broiler breeder males at this age, suggesting laying strain males may be more easily frustrated or aroused. While it is possible that broiler breeder males did not experience the same levels of conflict in the test situation due to lower levels of attack, escape andror sexual motivation, strong genetic selection for growth and appetite makes it likely broiler breeder males would have been more affected by hunger and frustration associated with feed restriction than feed-restricted laying strain males. Feed-restricted broiler breeders have been shown to display high levels of spot

Ž

pecking suggestive of frustration Kostal et al., 1992; Savory and Maros, 1993; Hocking

.

et al., 1996 . While feed restriction did impact on behaviour in the present experiment, the effects are difficult to interpret and there is no evidence that aggressiveness towards males was increased as a result of feed restriction during rearing. As our previous research also indicated that males fed ad libitum at sexual maturity were more aggressive towards males than feed-restricted males, we can lay to rest the issue of feed restriction as a causative factor in problems of aggressiveness in broiler breeder males. However, observations were not taken during feeding in either experiment and it is possible that feed-restricted males are more aggressive at the feeder. If so, aggression resulting from feed restriction must be specific to the feeding context, as opposed to general aggressive responsiveness of males.

With regard to our second hypothesis, the results of this experiment indicate that strain differences exist in aggressiveness of male domestic fowl. This conclusion does not come as a surprise as a genetic basis for aggression had been illustrated previously

ŽSiegel, 1959; Guhl et al., 1960 . Clearly, selection for fighting ability in Old English.

showed lower levels of aggression than game strain males and equivalent or lower levels than laying strain males. This low level of aggressiveness in broiler breeder males was surprising since we had expected that the high level of aggression towards males and particularly towards females seen in our previous studies and reported from the poultry industry, would also be expressed towards a model.

One of the factors that may have contributed to the unexpected results in this experiment was the effectiveness of the model as a stimulus for aggression for males of all treatments. Social encounters involve actions of approach and avoidance based on competing curiosity, companionship, attack, escape and possibly sexual motivations. The Barred Rock male used as a model in this experiment was intermediate in size and

Ž .

different in plumage relative to the strains of male tested. Lill 1968 found that domestic fowl reacted most aggressively to intruders of the same strain. Although the plumage of the model was foreign to all males, white broiler breeder males differed most significantly from the black and white mottled colour of the model. Also, since the model was smaller than broiler breeder males it may not been such a potent releaser of aggression for them as it was for the smaller game and laying strain males. The high rate of waltzing and crowing performed by game strain males suggests they may have been attempting to assess the fighting ability of the model. Crowing has been considered to be a signal of social status to other males, since dominant males crow more frequently and

Ž .

respond to crows of other males Leonard and Horn, 1995 . Whereas game strain males crowed significantly more than other males, crowing was one of the few behavioural elements frequently performed by broiler breeder males. This may suggest broiler breeder males were also responding to and assessing the model. However, it is also possible that crowing occurred in response to the novelty of the test environment. Low levels of aggression displayed by broiler breeder males to adjacent individuals in the home pens, as opposed to extremely high levels of aggression between neighbouring game strain males suggests size and plumage of the model relative to the test male cannot entirely account for the differences in aggressive responses.

Agonistic encounters involve both attack and appeasement displays. In this experi-ment, the stationary male model placed behind a Plexiglas barrier enabled us to focus on the motivation of males to initiate an aggressive encounter. In their review of aggressive

Ž .

motivation, Koolhaas et al. 1997 discussed the lack of correlation between behavioural scores of aggressiveness. They proposed ‘‘pro-active’’ and ‘‘reactive’’ classifications in relation to how an animal reacts to a wide variety of environmental challenges. It is possible that while broiler breeder males were less likely to initiate an aggressive

Ž .

encounter they may have reacted to displays of other males and females more

Ž .

Ž .

observation by Guhl et al. 1960 indicated that game cocks are extremely aggressive and do not show submissiveness, whereas junglefowl display both aggressiveness and submissiveness at high levels. Given the high levels of aggression displayed by game strain males in the home pens it is likely that game strain males would also react more aggressively to a live, threatening male.

The interaction between sexual and aggressive motivation is not clear. Leonard et al.

Ž1993a found that aggressiveness in males, reared in single-sex groups, decreased after.

males had been housed with females. The fact that males were penned with females in

Ž .

our previous studies Millman et al., 1996, 1997 could have affected aggressive motivation in several ways. Firstly, perhaps the males were more aggressive in this environment because they had a resource to compete for. In the current test situation, males were placed in a novel pen, with no food, water or social companions other than the model. In the group housing environment, access to females may have increased competition between males. Similarly, aggression to both males and females may also result from competition for food, water and space in crowded commercial barns. A second possibility is that sexual motivation, resulting from housing males with females, interacted with aggressive motivation. Hormones such as testosterone and oestrogen metabolites have been correlated with both sexual and aggressive behaviour in avian

Ž .

species Harding, 1986 . Perhaps aggressiveness was increased in the presence of a sexual stimulus with broiler breeder males. A third possibility is that laying strain males may be better able to establish and maintain a social hierarchy. Whereas aggressiveness was similar in laying and broiler breeder strain males in the current test situation, aggressiveness may have decreased more dramatically over time in laying strain males when group housed in our previous studies. The fact that our previous research indicated courtship behaviour was significantly lower, and chasing of females higher in broiler

Ž .

breeder than laying strain males Millman et al., 1996 suggests broiler breeder males may not perform and recognise social signals necessary for a stable social hierarchy. Further research is necessary to determine which if any of these factors are important as causative agents for the aggressive behaviour of male broiler breeder fowl towards female conspecifics.

In conclusion, results from this experiment indicate that the management practice of feed restriction is not a contributing factor to increased aggressiveness towards a male model by mature male domestic fowl. Furthermore, high levels of aggression by broiler breeder males is not a result of a general increase in aggressiveness in males of this strain as measured by motivation to initiate agonistic encounters.

Acknowledgements

References

Bastock, M., 1967. Courtship. Aldine Publishing, Chicago, IL.

Ž .

Bsary, R., Lamprecht, J., 1994. Reduction of aggression among domestic hens Gallus domesticus in the presence of a dominant third party. Behaviour 128, 311–324.

Craig, J.V., Bhagwat, A.L., 1974. Agonistic and mating behavior of adult chickens modified by social and physical environments. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 1, 57–65.

Craig, J.V., Jan, M.L., Polley, C.R., Bhagwat, A.L., Dayton, A.D., 1975. Changes in relative aggressiveness and social dominance associated with selection for early egg production in chickens. Poult. Sci. 54, 1647–1658.

Curtis, P.E., 1986. Mobbing behaviour by adult breeding chickens. Vet. Rec. 119, 273–274.

Duncan, I.J.H., 1970. Thwarting of sexual behaviour. The behaviour of the domestic fowl under conditions of drive interaction and goal inaccessibility. PhD Thesis, University of Edinburgh, pp. 162–167.

Duncan, I.J.H., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1971. Frustration and aggression in the domestic fowl. Anim. Behav. 19, 500–504.

Duncan, I.J.H., Hocking, P.M., Seawright, E., 1990. Sexual behaviour and fertility in broiler breeder domestic fowl. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 26, 201–213.

Ž

Feekes, F., 1971. ‘‘Irrelevant’’ ground pecking in agonistic situations in Burmese Red Junglefowl Gallus

.

gallus spadiceus . PhD thesis, University of Groningen, The Netherlands, pp. 1–112.

Guhl, A.M., 1949. Heterosexual dominance and mating behaviour in chickens. Behaviour 2, 106–120. Guhl, A.M., Craig, J.V., Mueller, C.D., 1960. Selective breeding for aggressiveness in chickens. Poult. Sci.

39, 970–980.

Harding, C.F., 1986. The importance of androgen metabolism in the regulation of reproductive behavior in the avian male. Poult. Sci. 65, 2344–2351.

Hocking, P.M., Maxwell, M.H., Mitchell, M.A., 1996. Relationship between the degree of food restriction and welfare indices in broiler breeder females. Br. Poult. Sci. 37, 263–278.

Hocking, P.M., Hughes, B.O., Keer-Keer, S., 1997. Comparison of food intake, rate of consumption, pecking activity and behaviour in layer and broiler breeder males. Br. Poult. Sci. 38, 237–240.

Koolhaas, J.M., de Boer, S.F., Bohus, B., 1997. Motivational systems or motivational states: behavioural and physiological evidence. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 53, 131–143.

Kostal, L., Savory, C.J., Hughes, B.O., 1992. Diurnal and individual variation in behaviour of restricted-fed broiler breeders. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 32, 361–374.

Ž .

Kruijt, J.P., 1964. Ontogeny of social behaviour in Burmese Red Junglefowl Gallus gallus spadiceus . Behaviour Suppl. XII, 1–201.

Lake, P.E., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1956. Diurnal rhythms in semen yields and mating behaviour in the domestic cock. Nature 178, 853.

Leeson, S., Summers, J.D., 1991. Commercial Poultry Nutrition. University Books, Guelph, Ontario, Canada. Leonard, M.L., Horn, A.G., 1995. Crowing in relation to status in roosters. Anim. Behav. 49, 1283–1290. Leonard, M.L., Zanette, L., Fairful, R.W., 1993a. Early exposure to females affects interactions between male

White Leghorn chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 36, 29–38.

Leonard, M.L., Zanette, L., Thompson, B.K., Fairfull, R.W., 1993b. Early exposure to the opposite sex affects mating behaviour in White Leghorn chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 37, 57–67.

Lill, A., 1968. Some observations of the isolating potential of aggressive behaviour in the domestic fowl. Behaviour 31, 127–143.

Marsteller, F.A., Siegel, P.B., Gross, W.B., 1980. Agonistic behavior, the development of the social hierarchy and stress in genetically diverse flocks of chickens. Behav. Processes 5, 339–354.

Mench, J.A., 1988. The development of aggressive behavior in male broiler chicks: a comparison with laying-type males and the effects of feed restriction. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 21, 233–242.

Mench, J.A., 1993. Problems associated with broiler breeder management. In: Savory, C.J., Hughes, B.O.

ŽEds. , Proceedings of the Fourth European Symposium on Poultry Welfare. Universities Federation for.

Animal Welfare, Potters Bar, UK, pp. 195–207.

Millman, S.T., Duncan, I.J.H., Widowski, T.M., 1996. Forced copulations by broiler breeder males. In:

Ž .

International Society for Applied Ethology. Col. K.L. Campbell Centre for the Study of Animal Welfare, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada, p. 50.

Millman, S.T., Duncan, I.J.H., Widowski, T.M., 1997. Extreme aggression in male broiler breeder fowl. In:

Ž .

Hemsworth, P.H., Spinka, M., Kostal, L. Eds. , Proceedings of the 31st International Congress of the ISAE. Research Institute of Animal Production, Prague, Czech Republic, p. 188.

Noldus Information Technology, 1993. The Observerw

, base package for DOS, Version 3.0 edn., Wagenin-gen, The Netherlands.

North, M.O., Bell, D.D., 1990. Commercial Chicken Production Manual, 4th edn. Chapman & Hall, New York, NY.

Ross Breeders, 1997. Ross Parent Stock Management Guide. Huntsville, AL, USA.

Rushen, J., 1983. The development of sexual relationships in the domestic chicken. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 11, 55–66.

SAS Institute, 1985. SASw

Introductory Guide for Personal Computers, Version 6 edn. SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA.

Savory, C.J., Maros, K., 1993. Influence of degree of food restriction, age and time of day on behaviour of broiler breeder chickens. Behav. Processes 29, 179–190.

Siegel, P.B., 1959. Evidence of a genetic basis for aggressiveness and sex drive in the White Plymouth Rock cock. Poult. Sci. 38, 115–118.

Ž .

Siegel, P.B., 1972. Genetic analysis of male mating behaviour in chickens Gallus domesticus : I. Artificial selection. Anim. Behav. 20, 564–570.

Widowski, T.M., Lo Fo Wong, D.M.A., Duncan, I.J.H., 1998. Rearing with males accelerates onset of sexual maturity in female domestic fowl. Poult. Sci. 77, 150–155.

Wilson, H.R., Miller, N.P., Nesbeth, W.G., 1979. Prediction of the fertility potential of broiler breeder males. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 35, 95–118.

Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1956. The agonistic and courtship behaviour of the brown leghorn cock. Br. J. Anim. Behav. 4, 133–142.

Wood-Gush, D.G.M., 1958. Genetic and experiential factors affecting the libido of cockerels. Proc. R. Phys. Soc. Edinburgh 27, 6–7.

Wood-Gush, D.M.G., 1960. A study of sex drive of two strains of cockerels through three generations. Anim. Behav. 8, 43–53.

Ylander, D.M., Craig, J.V., 1980. Inhibition of agonistic acts between domestic hens by a dominant third party. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 6, 63–69.