i

THE DEPICTION OF A (NATIONAL) HERO: PANGERAN DIPONEGORO IN PAINTINGS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY UNTIL TODAY

MASTER THESIS

In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master Study Program: Cultural Studies

Major: Art Studies

Written By: Nebojsa Djordjevic

S701208012

POSTGRADUATE PROGRAM SEBELAS MARET UNIVERSITY

SURAKARTA 2014

ii

THESIS

THE DEPICTION OF A (NATIONAL) HERO: PANGERAN DIPONEGORO IN PAINTINGS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY UNTIL TODAY

Written By Nebojsa Djordjevic

S701208012

Committee Name Signature Date

Supervisor I Dra. Sri Kusumo Habsari, M. Hum, Ph.D.

NIP 196703231995122001

--- __-__-2014

Supervisor II Dr. Hartini, M. Hum.

NIP 1950030011978032004

--- __-__-2014

Certified the requirements on Date: ...2014.

Head of Cultural Studies Study Programme Postgraduate Programme UNS

Prof. Dr. Bani Sudardi, M. Hum NIP 196409181989031001

iii

iv

THE DEPICTION OF A (NATIONAL) HERO: PANGERAN DIPONEGORO IN PAINTINGS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY UNTIL TODAY

THESIS

By

Nebojsa Djordjevic S701208012

Defended his thesis in front of examiners Acknowledge that he complies with requirements

On (date) ... 2014

Examination Committee:

Position Name Signature

Chairman Prof. Dr. Bani Sudardi, M. Hum

NIP 196409181989031001

...

Examiners 1. Dra. Sri Kusumo Habsari, M. Hum, Ph.D.

NIP 196703231995122001 2. Dr. Hartini, M. Hum. NIP 1950030011978032004

...

...

Acknowledge by: Director

Postgraduate Program Prof. Dr. Ir. Ahmad Yunus, M. S.

NIP 196107171986011001

Head of Study Programme Cultural Studies

Prof. Dr. Bani Sudardi, M. Hum NIP 196409181989031001

v

vi

STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICITY AND CONDITIONS OF PUBLICATION

I truthfully declare that:

1. Thesis entitled THE DEPICTION OF A (NATIONAL) HERO: PANGERAN DIPONEGORO IN PAINTINGS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY UNTIL TODAY is my own research work and there are no scientific papers that have been asked by others to obtain academic degrees and there is no this work or opinion was never written or published by another person, except those written with reference to the referent sources – mentioned in text and/or bibliography. If it proves that text of this have elements of plagiarism, then I am willing to accept the sanctions required, both to my master 's degree thesis along with cancelation of my title and procession according with the legislation in force .

2. Publication of part or all of the contents of this thesis in scientific journals or other forums must include the name of author, together with his advisor/mentorship team as well as naming UNS as the institution where this writing was published. If there is a violation of these provisions concerning publication, then I am willing to receive academic sanctions that apply.

Surakarta , ...

Student

Nebojsa Djordjevic, S701208012

vii

v

Nebojsa Djordjevic.NIM:S701208012.2014. The depiction of a (national) hero: Pangeran Diponegoro in paintings from the nineteenth century until today. THESIS. Supervisor I: Dra. Sri Kusumo Habsari, M. Hum, Ph D, II: Dr. Hartini, M. Hum. Postgraduate Program – Cultural Studies, Sebelas Maret University Surakarta.

ABSTRACT

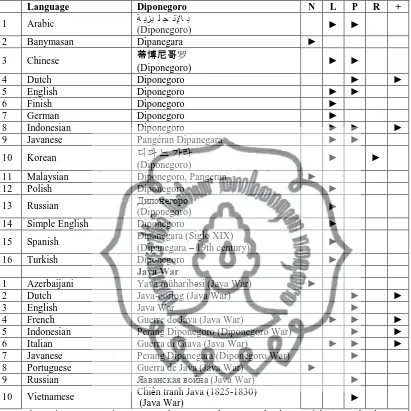

The objective of this research is to examine the idea of heroism in Indonesia and how it was shown in painting as a relatively new art form in this country. Pangeran Diponegoro (1785-1855) was rebellious prince in Java who fought against the Dutch. He entered paintings in Indonesia as soon as his rebellion ended. His appearance is one of the constant motifs in Indonesian paintings. The idea for this research was to show how Diponegoro was painted within different concepts.

This research is a qualitative study which primarily used Pierce semiotics (which includes sign in three aspects – icon sign, index signs, and symbol signs) to examine artworks and their meaning. Theoretical triangulation is achieved by using Postcolonial theory and its writing in analyses of these artworks. Cultural hybridity, identity, nationalism, nation-building, and other ideas are present in artwork and its signs.

With the end of the Java War, Javanese society experienced major changes in economical as well as in cultural aspects. Painting is an art form that was introduced to Javanese in this period. One of the first motifs in Indonesian painting was Pangeran Diponegoro. Briefly after Java War Dutch painter Nicolaas Pieneman painted a scene of submission of Diponegoro. The Javanese reply came few years after in painting of Raden Saleh, the first local artist who was trained in Europe. S. Sudjojono was one of the most prominent Indonesian painters and he painted Pangeran Diponegoro as national hero in 1979. In 1994 an emerging Indonesian artist paid homage to Diponegoro in his artwork and in 2007 Heri Dono painted his caricature painting of wrongful arrest of Diponegoro in twisted Indonesia. The idea of heroism changed over time and it has also looked different in different historical periods. Dutch painting of Pangeran Diponegoro had sense of pride and dignity in it. Yet it is an expression of Dutch ignorance, arrogance, and dominance over the Javanese. Javanese response is also controversial – some see it as proto-nationalistic painting, others dismiss it as servile. Indonesian paintings are full of nationalism and pride, but also with strong artistic messages of warning and critique toward society. While some signs have clear meanings which are shown in this research, the majority of them are fluid and open for discussion about ideas of nationalism, heroism, and identity in Indonesia.

Key words: national heroes, culture, Indonesia, Pangeran Diponegoro

vi

Nebojsa Djordjevic.NIM:S701208012.2014. The depiction of a (national) hero: Pangeran Diponegoro in paintings from the nineteenth century until today. THESIS. Supervisor I: Dra. Sri Kusumo Habsari, M. Hum, Ph D, II: Dr. Hartini, M. Hum. Postgraduate Program – Cultural Studies, Sebelas Maret University Surakarta.

ABSTRAK

Tujuan dari penelitian ini adalah untuk menguji ide kepahlawanan di Indonesia dan bagaimana itu ditampilkan dalam lukisan sebagai bentuk karya seni yang relatif baru di negeri ini. Pangeran Diponegoro (1785-1855) adalah pangeran yang memberontak dan berperang melawan Belanda di Jawa. Sosoknya menjadi terkenal dalam lukisan di Indonesia sesaat setelah pemberontakannya berakhir. Penampilannya adalah salah satu motif konstan dalam lukisan Indonesia. Ide untuk penelitian ini adalah untuk menunjukkan bagaimana sosok Diponegoro dalam konsep yang berbeda.

Penelitian ini merupakan penelitian kualitatif yang terutama digunakan dalam semiotika Pierce (tanda yang termasuk dalam tiga aspek - tanda icon, tanda indeks, dan tanda-tanda simbol) untuk memeriksa karya seni dan makna triangulasi teoretis mereka dicapai dengan menggunakan teori pascakolonial dan menulis dalam analisis karya seni ini . Hibriditas budaya, identitas, nasionalisme, pembangunan bangsa, dan ide-ide lain yang hadir dalam karya seni beserta tanda-tandanya.

Dengan berakhirnya Perang Jawa, masyarakat Jawa mengalami perubahan besar dalam ekonomi serta aspek budaya. Lukisan merupakan sebuah bentuk seni yang diperkenalkan ke Jawa pada periode ini. Salah satu motif pertama dalam seni lukis Indonesia adalah Pangeran Diponegoro. Sesaat setelah pelukis Java War Belanda Nicolaas Pieneman melukis adegan pengajuan Diponegoro. Balasan Jawa datang beberapa tahun setelah dalam lukisan Raden Saleh, seniman lokal pertama yang dilatih di Eropa. S. Sudjojono adalah salah satu pelukis paling menonjol Indonesia dan ia melukis Pangeran Diponegoro sebagai pahlawan nasional pada tahun 1979. Pada tahun 1994 muncul artis Indonesia memberi penghormatan kepada Diponegoro dalam karya seninya dan pada tahun 2007 Heri Dono melukis lukisan karikatur tentang penangkapan salah Diponegoro di dipelintir Indonesia. Ide kepahlawanan berubah dalam waktu ke waktu dan itu juga tampak berbeda dari periode sejarah yang berbeda. Lukisan Belanda Pangeran Diponegoro memiliki rasa kebanggaan dan martabat di dalamnya. Namun itu tampak sebagai ekspresi ketidaktahuan Belanda, arogansi, dan dominasi atas Jawa. Respon Jawa juga kontroversial - yang melihatnya sebagai proto-nasionalis lukisan, sementara yang lainnya menolak itu sebagai sepotong budak seni. Lukisan Indonesia penuh dengan nasionalisme dan kebanggaan, tetapi juga dengan pesan peringatan artistik yang kuat dan kritik terhadap masyarakat. Sementara beberapa tanda-tanda memiliki makna yang jelas yang ditunjukkan dalam penelitian ini, mayoritas dari mereka adalah ibarat cairan yang terbuka untuk diskusi tentang ide-ide nasionalisme, heroisme, dan identitas di Indonesia.

vii MOTTO

~

There is no need to carry me to another prison. My life is already ebbing away.

I suggest that you nail me to a cross and burn me alive.

My flaming body will be a torch to light my people on their path to freedom.

Gavrilo Princip (1894-1918) ~

Diponegoro is a combination of words

Which, when literally translated from Javanese to English, means: „The Light of the Country‟

viii

˷

To My Heroes: My Family and My Friends

ix

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. The First Western Look at Pangeran Diponegoro 43

1.1. A. J. Bick, charcoal sketch, 1830 43

1.2. A. C. Anthony, lithography, 1830 43

1.3. Note of 100 Indonesian rupiah from 1952 43

2. Nicolaas Pieneman: Submission of Diponegoro (1830-1835) 45

3. Javanese Look at Pangeran Diponegoro 52

3.1. Batik Perang Diponegoro 52

3.2. Pangeran Diponegoro from Buku Kedung Kebo 52

3.3. Portrait of young Pangeran Diponegoro 52

3.4. (and 3.5.)Wayang Diponegoro 52

4. Raden Saleh: The Arrest of Pangeran Diponegoro (1857) 55

5. Diponegoro as National Symbol in years after Independence 66 5.1. Equestrian Statue of Diponegoro in Monas – Monumen Nasional

5.2. National Monument, Jakarta. Work of Italian sculptor Cobertaldo 66 5.3. Basuki Abdulah „Diponegoro Memimpin Pertempuran‟ (1940-1960) 66

6. Pangeran Diponegoro in New Order Era (1966 – 1998) 69

6.1. Equestrian statue of Pangeran Diponegoro in main square in Magelang 69

6.2. Sasana Wiratama in Jogjakarta 69

6.3. Equestrian statue of Pangeran Diponegoro in Semarang 69

7. S. Sudjojono: Diponegoro (1979) 74

8. S. Sudjojono. 1979. Pasukan Kita Yang Dipimpin Pangeran Diponegoro (Our Soldiers Led Under Prince Diponegoro).

80

9. Djajeng Asmoro. 1980. Pangeran Diponegoro. 80

10.Agung Kurniawan: Homage to Prince Diponegoro (1994) 87

x

10.1.Pangeran Diponegoro (detail) 88

10.2.Kesatria Baja Hitam (Kamen Rider Black) – Japanese superhero 88

11.Heri Dono: Salah Tangkap Pangeran Diponegoro (2007) 91

12.Heri Dono. 2002. Raden Saleh Jadi Londo 96

13.Heri Dono. 2009. The Error of Pieneman‟s Perspective 96

14.Contemporary Look at Pangeran Diponegoro 98

14.1.Opera Diponegoro 98

14.2.Dramatic reading about Pangeran Diponegoro 98

14.3.Indieguerillas. 2012. This Hegemony Life 99

14.4.(and 14.5.) Manga-like Diponegoro 99

xi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ASRI Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia Indonesian Fine Art Academy HIK Hollandsche Indische Kweekschool Dutch East Indian School for

Teachers

IKJ Institut Kesenian Jakarta Institute for Art Jakarta ISI Institut Seni Indonesia Indonesian Institute for Art ITB Institut Teknik Bandung Techincal Institute in Bandung IVAA Indonesian Visual Art Archive

KBBI Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia Great Dictionary of Indonesian LEKRA Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakyat Institute for People‟s Culture

PERSAGI Persatoean Asal Gambar Indonesia Association of Indonesian Drawing Specialists

PKI Partai Komunis Indonesia Communist Party of Indonesia POETRA Poesat Tenaga Rakjat Centre for the People‟s Poаer

S. Sindudarsono First name of Sudjojono

SIM Seniman Indonesia Moeda Young Indonesian Artists

UGM Universitas Gadjah Mada Gadjah Mada University, Jogjakarta UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNS Universitas Negeri Sebelas Maret Sebelas Maret University, Surakarta VOC Vereeningde Oost-Indishe

Compagnie

United East India Company

xii EXTRAS

LIST OF FIGURES

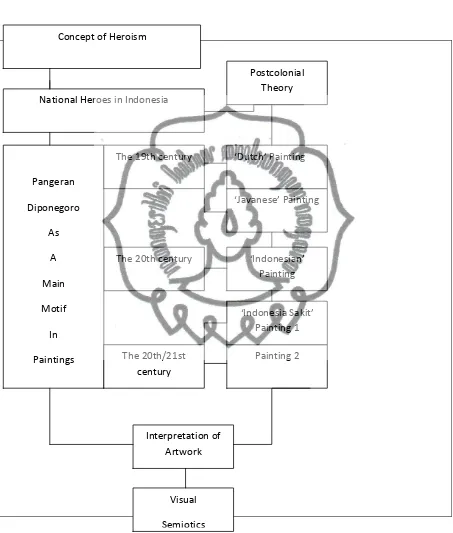

Figure 1 Framework of the research (Chapter 2, Subchapter D) 31

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Primary Data (Chapter 3, Subchapter C) 36

LIST OF APPENDICES

Appendix 1 List of National Heroes in Indonesia (Table 1) 110

Appendix 2 Statistics from List of National Heroes 117

Appendix 3 Poster of National Heroes in Indonesia 124

Appendix 4 Web visibility of key terms from research (Table 2) 125

Appendix 5 Analyses of Table 2 126

CONTENT

1.2. Heroes and National Heroes in Indonesia 9

1.3. Pangeran Diponegoro – The National Symbol 13

2. Indonesian Painting 15

A. Location and Time of Research 34

CHAPTER IV – ANALYSES 40 A. The 19th century - Pangeran Diponegoro: Villain and Hero 40

1. The 19th century in Indonesia 40

2. Art history of the 19th century 41

3. Western Eyes: Nicolaas Pieneman‟s Vision of Pangeran Diponegoro 41

3.1. Biography of Nicolaas Pieneman 41

3.2. Submission of Diponegoro (1830-5) – History and Signs 42

4. Javanese Eyes: Raden Saleh‟s Vision of Pangeran Diponegoro 50

4.1. Biography of Raden Saleh 50

4.2. Arrest of Pangeran Diponegoro (1857) – History and Signs 51

5. Pangeran Diponegoro: Villain, Rebellion, or Hero 61 B. Indonesian art (1950-1990): Depicting a National Hero 64

1. The 20th century in Indonesia: History of Nation and Art 64

2. Pangeran Diponegoro: National Hero in Art 65

3. Indonesian Eyes: S. Sudjojono‟s Vision of Pangeran Diponegoro 70

3.1. Biography of S. Sudjojono 70

3.2. Diponegoro (1979) – History and Signs 73

4. Pangeran Diponegoro: One Brick in Wall of Nation 81 C. Indonesian art (1990-today): Nation in need of (Super) Hero 84

1. Art and Life of Indonesia Today 84

2. Contemporary Indonesian Eyes Look Toward Pangeran Diponegoro 86

2.1.1. Biography of Agung Kurniawan 86

2.1.2. Homage to Prince Diponegoro (1994): History and Signs 87

2.2.1. Biography of Heri Dono 90

2.2.2. Salah Tangkap Pangeran Diponegoro (2007): History and Signs 91

3. Who Are the Heroes Now and Do We Need Them? 97 D. Depiction of Pangeran Diponegoro from the 19th until today 100

CHAPTER 5 – CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 103

3 CHAPTER I

A. Background

The concepts of hero and heroism are hard to grasp. Definitions of these terms go from early heroes in literature whose adventures were written thousands of years ago until movie about superheroes today. The concept of heroism has been confused with related, possibly contributing factors such as altruism, compassion, and empathy, and identified with popular celebrities, role models, and media-created fantastic-heroes.

The term “hero” in literature studies means main character of a storв. The same

term is used in different art forms that involve action and movement. There is always a hero within a narrative, including in a dynamic painting, theater play, or movie. First narratives in the world included stories about divine creatures, common people, and connectors between these two worlds, and were often told through a hero and his actions. Historian Hughes-Hallett writes: There are men, wrote Aristotle, so godlike, so exceptional, that they naturally, by right of their extraordinary gifts, transcend all moral judgment or constitutional control: „There is no law which embraces men of that caliber: they are themselves law‟(in Zimbardo, 2011). Among the earliest surЯiЯing literature аorks is „Epic of Gilgamesh‟ аhich centers on heroic figure Gilgamesh.

Today we also live in a world full of heroes. Newspapers always include articles about heroic acts. Superhero movies are an extremely popular genre. Spiderman is a

superhero character аho first appears in comics around the 1960‟s in U.S. It is one of the

most famous examples of the Marvel school of comics and „production‟ of superheroes.

Eventually, due to his popularity, this character left comic books and entered the worlds of animation, T.V. series, and eventually film. There was even a trilogy about Spiderman spanning 2002 to 2007. In the second decade of the 21st century, a new Amazing Spiderman movie franchise began. The first movie was released in 2012 and the second part will arrive in cinemas around the globe in April/May 2014.

Superheroes movies usually come from American tradition of (super) heroism. Over there it is long tradition of production of superheroes – first in comic books, then TV formats, finally film, and these days films in its new formats – three (or even five)

dimensional cinema experience. It is also followed by video games, applications for smart-phones, the Internet prequels, sequels, parodies etc. TeleЯision shoаs are more „glocal‟ (global and local). “Idol”, a shoа created in the UK in 2001 and has inspired spin-off almost in every part of the world. In Indonesia in particular these singing competitions are really popular. With global franchises such are „Voice‟, „I haЯe talent‟, and the

aforementioned „Idol‟ – Indonesia has its own versions where people compete to be dangdut stars for example.

State wanted to reconcile two worlds – one of „Idols‟ and popular culture made heroes and one with men and women who were fighting for country and the national ideology made heroes. Every 10th of November is Indonesian day of Heroes. In 2013 the slogan for this day was Pahlawanku – Idolaku (My hero – my idol). National heroes play an important role in history and culture in many parts of world. Maria Todorova is a Bulgarian born American historian and philosopher. She used in her book Imagining Balkans (2009) Seid‟s concept of Others and Orientalisation and place it in South-East European region of Balkans. In her other book Bones of Contention - The living archive of Vasil Levski and the making of Bulgaria‟s national hero (2009) she discussed more about one national hero. Vasil Levski is a fighter for Bulgarian independence in the 19th century when this country was still under Ottoman Empire rule. Nowadays he is the national hero per excellence and Todorova is trying to answer why and how (Todorova, 2009).

Linas Eriksonas is a historian and philosopher interested in state identity and nationalism. In his book (derived from his PhD thesis) National Heroes and National Identities (2004) he is examining the heroism and connection with state and national identity and ideology in three different European states: Scotland, Norway, and his native Lithuania. While these researchers were made by historians and it is questionable how and who decides that one is a national hero and other is not, in Indonesia that is a task of state.

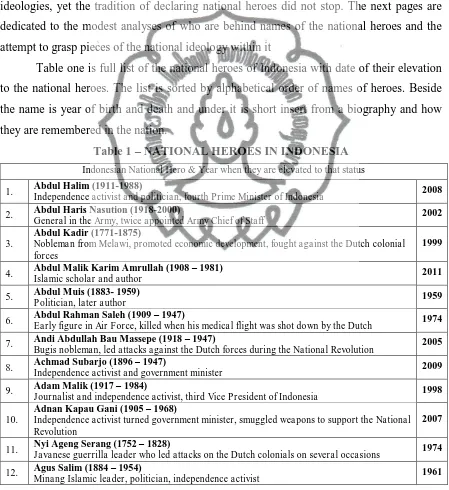

Indonesian state apparatus every year since 1959 declares new national heroes. There are sets of standards and criteria that one needs to fulfill to enter the list. In 2013 three more persons were made into this honorable list and until now almost 160 (159 to be exact) persons from various backgrounds are called national heroes of Indonesia. Indonesia is a relatively new country, during previous centuries different part of Archipelago were

ruled with different dynasties, powers, etc. List of national heroes starts from the 17th century. Sultan Agung (1591-1645) is first proto-Indonesian, his fight and resistance toward up-coming Dutch and their colonization is now looked as fight of Indonesian glory historical character against powerful, foreign invader.

Foreign invader brought a lot of changes into the lives of people in Archipelago and one of the imported products is – painting. History of art and representative art in Indonesia can not be traced in same way like in the West. Father of Indonesian paintings is Raden Mas Saleh. His most popular painting is depicting Javanese rebellion Pangeran Diponegoro and his capturing (1857). Before him, one Dutch artist painted this scene and he called it – Submission of Diponegoro (1835). From that moment until today Pangeran Diponegoro - remarkable historical figure and national hero per excellence frequently enter Indonesian paintings. Indonesian art is really vivid and recognized in global arena. Indonesian artist dare to say also something about the national ideology which surrounds them, and that includes questions about national heroes. State driven production of national heroes and artist reply to this movement will be main topic of this research. The research will focus on depiction of Pangeran Diponegoro from the 19th century painting until today.

B. Problem Formulation

1. What is the meaning behind the depiction of Pangeran Diponegoro from the 19th century paintings until present day artworks?

2. How were the concepts of national heroism and national ideology reflected in the depiction of Pangeran Diponegoro?

3. What are the trends in the depiction of national heroes in the present day Indonesian art and where Pangeran Diponegoro is in the Indonesian art today?

C. Objectives of the research

According to research questions, the objectives of this research will be:

1. Understanding the development of the concept of nationalism in Indonesian art through painting of Raden Mas Saleh in the mid-19th century until today.

2. Assessing the value of national hero in art, as well as understanding the evolution of the concepts of national ideology, heroes, and heroism, and how they overlaps with art.

3. Re-affirming the importance of the national hero for the future art, as well as the development of national identity.

D. Significance of the Research

1. Theoretical Significance

a. This research will help in understanding the concept of national heroism and its relationship with art.

b. The results of this research will enrich research in cultural studies

2. Practical Benefit

a. Hopefully this research will show that national heroes are integral part of Indonesian contemporary culture and with that it opens possibilities for studies of national heroism and its connect to other fields – literature, popular culture, anthropology, feminism, and others.

b. Pangeran Diponegoro is a perfect symbol of national hero through works of art. This is rather new look on his place in history and nationalism of Indonesia. Research will therefore also open possibilities to study Pangeran Diponegoro (as well as other historical figures) in different point of view.

c. Finally this research will aim to show that painting is not alienated art form from other art forms that have longer tradition in Indonesia. It is vivid and integral part of Indonesian art, and like that it deserves better and greater research and preservation.

7 CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

A. Main Concepts

1. Heroism

1.1. The word for Hero

To understand the concept of heroism in Indonesia one first needs to understand the meaning of the word itself. This section begins with an explanation of words for heroes in English, Indonesian, and the Javanese language, as the concept of hero can be difficult to understand, and the usage of heroes varies greatly. This will be shown in the next chapters, as a steady foundation for understanding the concepts of hero and heroism requires an understanding of similarities between the terms for hero in languages that are used for this research.

There are different sources, with more or less the same meaning of the word hero in the English language. From one source etymology of the word is from the late 14th century . The аord is coined in the English language in 1387. The definition of the аord is “man of superhuman strength or physical courage.” Origin of the аord is from ancient

Greek: heros (ἥ ω ), demi-god (a variant singular of which was heroe), but the word comes in English from Latin heros, hero. Originally defender, protector, from Proto Indo-European root word ser- which has a meaning to watch over, protect (can be compared to Latin word servare - to save, deliver, preserve, protect). Second meaning man who exhibits great bravery in any course of action is from 1660s. In the other sense as of chief male character in a play, story, etc it was first recorded in the 1690s. (Skeat, 2005)

Oxford Dictionary of English (2010) defines the word in two aspects. Second one is definition of hero sandwich (alternative American name for submarine sandwich). So, here there will be mentioned only the meaning of the first entry: 1) hero, noun (Plural heroes): a person, typically a man, who is admired for their courage, outstanding achievements, or noble qualities, example is: a war hero. 2) chief male character in a book, play, or film, who is typically identified with good qualities, and with whom the reader is expected to

sympathize, example: the hero of Kipling‟s story. 3) Hero in mythology and folklore is a person of superhuman qualities and often semi-divine origin, in particular one whose exploits were the subject of ancient Greek myths.

Words derived from hero are: heroism, the drug heroin (because of its euphoric feeling that the drug provides, but link between hero and heroine is blurry), anti-hero, and here we will examine a more female version and hero-worshiping. Female version of hero

is heroine. This form started to be used in the 1650s. It comes from Latin heroine, heroina

(plural heroinae) - a female hero, a demigoddess” – for example Medea. It is originally

Indonesian word Pahlawan also has interesting connotations. The most important Indonesian dictionary Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia (Great Indonesian Dictionary) defines the word in its 2005 edition:

Pahlawan (Sanskerta: phala-wan yang berarti orang yang dari dirinya menghasilkan buah (phala) yang berkualitas bagi bangsa, negara, dan agama) adalah orang yang menonjol karena keberaniannya dan pengorbanannya dalam membela kebenaran, atau pejuang yang gagah beran.

[Which can be translated into English: Pahlawan (Indonesian word for hero comes from Sanskrit phala-аan аhich means person аho produces „fruit‟ (phala) which has quality for his nation, country, and religion) is person who stands out because of his bravery and sacrifice for the right cause or who achieved glorious victory.] (KBBI, 20081)

Indonesian language are: wira, wirawan, (from Javanese mentioned below), tokoh utama yang berani dan hormat (for character in art work who has attributes of bravery and respect

– mentioned above) also pelaku utama, pemeran utama,bahadur (knight) and hero itself. Words unrelated to heroism, derived from pahlawan are pahlawan bakiak – a term for a husband who is very afraid of his wife and pahlawan kesiangan – people who want to work hard after the hard times are over and often want credits for their work.2

In Javanese language there are several words for expressing the concept of hero. Wira, wirawan (and its slightly nobler form wirya) is more an alus (refined) word for

manly, brave, and courageous. It is frequently used as an element in compound names: there are Javanese (Indonesian) male names such are Wira or Wirapandya. The word sura

has a similar meaning and is likewise more commonly found in the five-syllable names of males, not just in literature, but in general name giving as well. Example of given male names with this root are Sura and Surapati. Satria does not mean hero exactly, but more a warrior or a member of the refined, aristocratic classes. These words derive mostly from Sanskrit which has greatly enriched the Javanese lexicon for well over a thousand years.

Pahlawan of Persian origins is the most common word for hero in Indonesian and is also used in Javanese (Mangusuwito, 2002).

1.2. Heroes and National Heroes in Indonesia

Indonesian language does not use the same expression for the main character in artwork (thus in culture) and to address great men in history and national heroes, thus researches of heroism within this common point are scarce in Indonesia. Nevertheless, Lombard, D. and Pelras, C. (1993) in Asian Mythologies defines cultural heroes in Insular South-East Asia (which corresponds to Indonesia and The Philippines) in four distinctive categories: 1) Heroes of Oral Myth, 2) Heroes of Written Accounts, 3) Heroes Linked to Successive Acculturation (India, China, Islam) and 4) Modern Heroes3

Cultural heroes represent ideal figures that humans follow and respect. Examples given to in encyclopaedia are legends of creation of world in oral traditions. How the world

2 Ibid

3 Lombard, D. and Pelras C. 1993. Cultural Heroes of Insular Southeast Asia, Page 167-173 in Yves Bonnefoy (edt.) Asian Mythologies, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

was created in different cultures around Archipelago. Legendary prince Panji and his adventures is an example of a hero of the written legends. Cultural heroes can be re-born and re-shaped with acculturation, adapt to new circumstances. There are numerous examples; one is a traditional Javanese story of Wali Sanggo - they were nine saint men who brought Islam to Java.4

The last type of a cultural hero, which is mentioned in this book, is perhaps not as far removed from the preceding heroes as one may think: these are national heroes that the independent states of insular Southeast Asia have chosen to symbolize the birth of the new society

Rizal and Aguinaldo for the Philippines, and Hasanuddin, Kartini, and Imam Bonjol for Indonesia. Although they are historical, each of these figures has myth-simplified official biographies, widely disseminated, particularly through schools – his commemorative ritual, his stereotyped iconography, etc. The frequency with which they are mentioned shows how much modern societies, from that point of view, have trails in common with so-called primitive societies.5

The cult of national heroes in Indonesia was introduced by its first president Sukarno. Principal initiative was to remake Indonesian memory around a revolutionary theme. In a set of decrees between 1957 and 1963 he laid down the procedure for declaring as national heroes people who had resisted colonialism or served the cause of the independence. Remuneration was arranged for the descendents of those, so the names (creating a small industry of lobbyists) and the manner of commemorating them through monuments, anniversaries, school texts and street names was prescribed (Reid, 2005).

The second Indonesian president, Suharto, was not all that interested in celebrating revolution, but he did take the theme of anti-Dutch struggle. The fact that many of those already declared heroes had died fighting the Dutch made it a small step to portray armed struggle as the leitmotif of national history, and the national army as its natural contemporary upholder. By 1992, twenty-three military officers had been added to the pantheon of national heroes, more than a third of the total declared under Suharto. (Reid, 2005)

4 Ibid 5 Ibid

The National Hero of Indonesia (Indonesian: Gelar Pahlawan Nasional Indonesia) is the highest-level title awarded in Indonesia. It is posthumously given by the Government of Indonesia for actions which are deemed to be heroic – defined as actual deeds which can be remembered and exemplified for all time by other citizens or extraordinary service furthering the interests of the state and people.

The Ministry of Social Affairs6 gives seven criteria which an individual must fulfil, as follows:

1. An Indonesian citizenwho is deceased and, during his or her lifetime, led an armed struggle or produced a concept or product useful to the state;

2. Have continued the struggle throughout his or her life and performed above and beyond the call of duty;

3. Have had a wide-reaching impact through his or her actions; 4. Have shown a high degree of nationalism;

5. Have been of good moral standing and respectable character; 6. Never surrendered to his or her enemies; and

7. Never made an act which taints his or her legacy.

Nominations undergo a four-step process and must be approved at each level. A proposal is made by the general populace in a city or regency to the mayor or regent, who must then make a request to the province's governor. The governor then makes a recommendation to the Ministry of Social Affairs, which forwards it to the President, represented by the Board of Titles (Dewan Gelar); this board consists of two academics, two persons of a military background, and three persons who have previously received the award or title. Those selected by the President, as represented by the Board, are awarded the title at a ceremony in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta. Since 2000, the ceremony has been occurring in early November – coinciding with Indonesia's Heroes' Day (Hari Pahlawan)7.

The legal framework for the title, initially styled National Independence Hero (Pahlawan Kemerdekaan Nasional), was established with the release of Presidential Decree

6

Data for this section were retrieved from official page of The Ministry of Social Affairs http://www.kemsos.go.id/modules.php?name=Pahlawan in December 2013

7 Ibid

No. 241 of 1958. The title was first awarded on August 30th, 1959 to the politician turned writer Abdul Muis, who had died the previous month. This title was used for the rest of Sukarno‟s rule. When Suharto rose to power in the mid-1960s, the title was given its current name. Special titles at the level of National Hero have also been awarded. Hero of the Revolution (Pahlawan Revolusi) was given in 1965 to ten victims of the failed 30 September Movement coup, while Sukarno and former vice-president Mohammad Hatta were given the title Proclamation Heroes (Pahlawan Proklamasi) in 1988 for their role in reading the Proclamation of Indonesian Independence and in 2012 they also became National Heroes. 8

A total of 147 men and 12 women have been deemed national heroes, most recently Rajiman Wediodiningrat, Lambertus Nicodemus Palar and Tahi Bonar Simatupang in 2013. Indonesia is perhaps the only country with ever-increasing number of „national

heroes‟ officiallв recogniгed bв the state (Abdullah, 2009). These heroes haЯe come from

all parts of the Indonesian archipelago, from Aceh in the west to Papua in the east. They represent numerous ethnicities, including native Indonesians, ethnic Chinese, and Eurasians. They include prime ministers, guerrillas, government ministers, soldiers, royalty, journalists, and a bishop. The procedure may have started from Sukarno, but only with the New Order has it got its relatively well-established procedure. Abdullah (2009) uses picturesque comparison to explain this procedure:

Since then [New Order] it becomes obvious that state recognition of national heroes

practicallв a аaв for state to compose „national familв album‟. The inclusion in the „portraits into the national album‟ is official national recognition of struggles and

sacrifices they have made to the nation and tanah air, the homeland. It is understandable that every province would look deep into its respective history to see whether there was someone in the past who had sacrificed and given his or her life to the glory of the nation and tanah air. (Abdullah, 2009:442)

8 Ibid

1.3. Pangeran Diponegoro9 - The National Symbol

Diponegoro has the same symbolic value as Vasil Levski10 for Bulgarian nationhood and the idea of a national hero. He is Javanese. He was born in heartland of Javanese high culture – Yogyakarta. He was a son of a newly established Javanese royalty (after tearing Surakarta keraton in two branches – one in Yogyakarta and one in Surakarta who somehow continued the line of previous rulers). He did not become the heir of throne, rather he was devoted to his piece of land and peasants who were living and working for him. He saw injustices and intrigues of the Dutch. He stood against it. He led a five years exhausting war/revolution. Java was changing dramatically in his time, becoming closer to the West. He saw himself also as a religious leader. He was tricked, captured and he died in exile in South Celebes far from his native land.

His presence is still notable in Indonesia. UNESCO list of World Memory bear two documents from Indonesia and one is „Babad Diponegoro‟ – first autobiography in Javanese literature. He was an inspiration for controversial Indonesian Communist Party, but also to army after whom Central-Javanese Region was named. The same goes for some big ships that Indonesian Military Navy possesses. Central-Javanese capital Semarang is the home to the biggest University in the city which was named after him. Main streets in almost every big city in Indonesia (or at least in Java) are named after him. Diponegoro is a sign of Indonesia. He is one of the few figures that are so closely connected with the idea of Indonesia. Sometimes they can look like opposites (Communist Party vs. Army, secular

ideas of higher education Яs. Diponegoro‟s strong religious feelings, JaЯa Яs. Sulaаesi) but

these opposites make Indonesia.

Diponegoro was born on 11 November 1785 in Yogyakarta, and was the eldest son of Sultan Hamengkubuwono III of Yogyakarta. When the sultan died in 1814, Diponegoro renounced the succession to the throne in favor of his younger half

9 Peter Carey is British historian who wrote extensively about Pangeran Diponegoro, and he is using English-Javanese coin for him - Prince Dipanegara. In this study Indonesian version of his name – Pangeran Diponegoro will be used, and together will all given names it would not be put in Italic font style, unlike other Indonesian words.

10 Vasil Levski is national hero of Bulgaria and topic of research of Maria Todorova (2009) which is mentioned in introduction and later on in literature review

brother, Hamengkubuwono IV who was supported by the Dutch. Being a devout Muslim, Diponegoro was alarmed by the loosening of religious observance at his half brother's court, as well as by the court's pro-Dutch policy (Carey, 2007).

In 1821, famine and plague spread around Java. His half brother Hamengkubuwono IV (r. 1814-1821) who had succeeded to the throne after their father had died. He left only an infant son as heir, Hamengkubuwono V. When the young ruler was appointed as a new sultan, there was a dispute over his guardianship. Diponegoro was again renounced, though he believed he had been promised the right to succeed his half brother. This series of natural disasters and political upheaval finally erupted into a full scale rebellion (Carey, 2007).

Dutch colonial rule was becoming unpopular by the local farmers because of tax rises, crop failures and by Javanese nobles because the Dutch colonial authorities deprived them of their right to lease land. Because the local farmers and many nobles were ready to support Diponegoro and because he believed that he had been chosen by divine powers to lead a rebellion against the Christian colonials, he started a holy war against the Dutch. Dipenogoro was widely believed to be the Ratu Adil, the Just Ruler predicted in the Pralembang Joyoboyo (Carey, 2007).

The beginning of the war saw large losses on the side of the Dutch, due to their lack of coherent strategy and commitment in fighting Diponegoro's guerrilla warfare. Ambushes were set up, and food supplies were denied to the Dutch troops. The Dutch finally committed themselves to controlling the spreading rebellion by increasing the number of troops and sending General De Kock to stop the insurgencies. De Kock developed a strategy of fortified camps (benteng) and mobile forces. Heavily-fortified and well-defended soldiers occupied key landmarks to limit the movement of Diponegoro's troops while mobile forces tried to find and fight the rebels. From 1829, Diponegoro definitely lost the initiative and he was put in a defensive position. Many troops and leaders were defeated or deserted (Carey, 2007).

In 1830 Diponegoro's military seemed near defeat and negotiations were started. Diponegoro demanded to have a free state under a sultan and he wanted to become the Muslim leader (caliph) for the whole of Java. In March 1830 he was invited to negotiate

under a flag of truce. He accepted but was taken prisoner on 28 March despite the flag of truce. De Kock claims that he had warned several Javanese nobles to tell Diponegoro he had to lessen his previous demands or that he would be forced to take other measures. The Dutch exiled him to Makassar (Carey, 2007).

2. Indonesian Painting

Representational art in Indonesia has a long tradition. There are numerous sites all over the archipelago that indicate the presence of visual arts from early ages – there are caves that are painted as well as ceramics, jewellery, and other decorative objects that date back to pre-history. Classical Indonesian art is one that is addressed to flourishing Javanese and Balinese kingdoms and art that was made under important rulers to show their power. Beautiful temples are scattered all over Java and Bali. When Islam was introduced to the archipelago, it brought classical elements of Islamic art, including architecture in first place one concerning building and decorating mosques.

In the 19th century, with emerging colonialism, painting as a new form of art emerges in the island of Java and Bali especially. Balinese art had different periods and schools and hereby we will focus more on the development of painting in Java because it influenced development of art in the whole nation, but also due to the fact that it follows main ideological and national ideas that will shape Indonesia. Mooi Indie or Hindia Jelita

(Beautiful Indies) was a period of Indonesian painting at the beginning of the 20th century. It shows ideological Indonesia with hard-working people working in beautiful rice fields, scenes of every day easy and nice lives, landscapes with lavish mountains, beautiful, modest, but yet seductive Indonesian girls. Painters were both Indonesians and Westerners who were living in Indonesia at that time. In 1938 Persagi (Persatuan Ahli Gambar Indonesia) was created as a response to the previous movement, where artists considered that their role was more engaging and they needed to show more real life of people, with their struggles and sufferings. (Kusuma-Atmadja et al. 1990)

With the World War II and the Japanese occupation paintings served as propaganda for achieving the national goal – a united and free Indonesia. There were numerous art groups created between 1942 until 1950. In 1950 Indonesia was de facto independent from

the Netherlands and those first years of Independence were marked by major turbulences. That dynamic was illustrated in groups of artists that were created, all with different political or religious agendas.

More important for Indonesian art was the creation and establishment of art academies in Java and artist organizations connected with these centres. From their inception, three schools have dominated the Indonesian art scene: IKJ (Insitut Kesenian Jakarta) – Art Institute in Jakarta, ITB (Institut Teknologi Bandung) – Technology Institute in Bandung, and ISI (Institut Seni Indonesia, created as ASRI Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia – Fine Art Academy of Indonesia back in days, now Insitute of Indonesian Art) Yogyakarta. In 1970s Indonesian art started also to have strong Post-Modernistic discourse following world trends. Not long after Indonesian art entered in the world art arena and after 1990s Indonesian art has had its ups and downs but until today continues to surprise and intrigue art lovers from all over globe. (Kusuma-Atmadja et al. 1990)

With this short review of art we can see that Indonesian art is connected with its modern history. In classical times artists were merely craftsmen and somehow moderators between divine forces, rulers and the common people. Beginning in the 19th century painters and Indonesian intellectuals start to shape the future of the Indonesian nation. Once, Indonesia was independent they continue to work together with politicians in shaping the national ideology. For thirty years, Indonesia was under one regime that did not allow free artistic thinking, so the influence of art quitted down out at first, but then together with

the people‟s resistance, artists started to become braЯer and to question authorities. Since

1999, Indonesia has again been questioning its position in the wider world, and in this process of re-positioning and re-shaping the identity artists do play an active role.

B. Theoretical Basis

1. Postcolonial Theory

There is a theoretical field in cultural studies that can be named the „difference

theorв‟ Milner and Broаitt (2002) said it „has been characterised bв an attempt to theorise

historical difference, especially in respect of gender and sexuality, nationality, race and

ethnicitв.‟ While this concept appears Яague and diЯerse it centres on questions of the identitв. As Hall (1993) adds „there are also critical points of deep and significant difference which constitute „аhat we really are‟; or rather since history has intervened

–„аhat we have become‟.

In this research, questions concerning the national identity will be examined, primarily those concerning creating and sustaining ideas of nationalism and theories that are put together under one term – post-colonial theory. One of the greatest resources for studying nationalism in South-East Asia is Benedict Anderson‟s „Imagined Communitв‟ (1996). He argues how culture, in the first place language – primarily printed one (via books, press) helped to shape the national identitв аhich he equals аith „imagined

communities‟. He giЯes explanation for nation building processes in all parts of the аorld

and he gives tools to demonstrate how diverse this process is.

For this research the most important findings are the ones from South-East Asia. Anderson conducted his most important research in South-East Asia. Indonesia, as it is understood today, never actually existed. It is a product of the Dutch colonization; the settlers referred to their territory as the East India. „As its hвbrid-pseudo-Hellenic name suggests, its stretch does not even remotely correspond to any pre-colonial domain; on the

contrarв ... its boundaries haЯe been left behind bв the last Dutch conquests‟. (Anderson,

1996) Nevertheless, that was enough for the newly formed Indonesian intelligentsia to

„imagine‟ this communitв as one entitв. He argues that people from north and north -western Sumatra had more connections with the people on the Malay peninsula than those in Ambon. Yet one of the biggest reasons the Indonesia project succeed where others failed (i.e. United Indochina) was the fact that the Dutch tolerated the Indonesian language as

„lingua franca‟ of the Archipelago. Around the turn of the century, Indonesia's lingua franca will become a powerful tool in the nation-building process.

A national culture is not folklore, nor an abstract populism that believes it can discover the people's true nature. A national culture is the whole body of efforts made by a people in the sphere of thought to describe, justify and praise the action through which that people has created itself and keeps itself in existence. A national culture in underdeveloped countries should therefore take its place

at the very heart of the struggle for freedom which these countries are carrying on (Fanon, 1963).

When аe talk about national identities (and cultures) аe must mention that: “more

than three-quarters of the people living today have had their lives shaped by the experience of colonialism (Barker, 2005)”. In those countries (аith colonial experience) after getting rid of colonial powers writers and theoreticians start to write and discuss about post-colonialism. Postcolonial theory explores postcolonial discourses and their subject positions in relation to the themes of race, nation, subjectivity, power, subalterns, hybridity and creolization (Barker, 2005). There are numerous approaches and definitions of Postcolonial theory, for this research one useful is mentioned under.

[Postcolonial theorв]…Seeks to speak to the vast and horrific social and psychological suffering, exploitation, violence and enslavement done to the powerless victims of colonization around the world. It challenges the superiority of the dominant Western perspective and seeks to re-position and empower the marginalized and subordinated Other. It pushes back to resist paternalistic and patriarchal foreign practices that dismiss local thought, culture and practice as uniformed, barbarian and irrational. It identifies the complicated process of establishing an identity that is both different from, yet influenced by, the colonist

аho has left‟. (Parsons and Harding, 2011)

It is still questionable where domains of postcolonial theory are. Some argue that even the American culture can be put into post-colonial frame. Here we would address to the findings and ideas of those theoreticians whose work is relevant to this research. Edward Said in his book Orientalism argues how French and British colonist who in the Middle East started to construct Orient or East as a contrast to West which authors will later call this Occident and Occidentalism. He argued that this construction was built a binary opposition model in which Western values can be described as: progressive, liberal, secular, educated, democratic, open, and so on. Eastern ideals would conversely be described as: conservative, closed, religious - primarilв Islamic, limited minded, etc. „The major component in European culture is precisely ... the idea of European identity as a superior one in comparison with all the non-European peoples and cultures‟ (Said, 2003)

Orientalism is also possible inside the West. Maria Todorova is a Bulgarian born

historian and philosopher аho liЯes and аorks in the US. TodoroЯa incoprorated Said‟s

concept of Orientalism in European region of Balkan in her book Imagining Balkans

(2009). She analysed what the term Balkans meant within a cultural frame. She explained the origin of the name, and how from the 19th century and with the falling of the Ottoman Empire and rise of national states in it, Europe (West) started to become interested in this region. It shows further how Europe was always between accepting it in its own cultural (and with that economical, political and every other way) circle and rejecting it with great passion and discussion over its monstrosity, brutality, and primitivism.

Postcolonial theory grows from literature theory and its first authors were ones of Indian origins, Homi Bhabha is one of the most famous critical theorist and Postcolonial theory contributor. One of his central ideas is that of hybridization, which, taking up from Edward Said's work, describes the emergence of new cultural forms from multiculturalism. Instead of seeing colonialism as something locked in the past, Bhabha shows how its histories and cultures constantly intrude on the present, demanding that we transform our understanding of cross-cultural relations. His work transformed the study of colonialism by applying post-structuralist methodologies to colonial texts.

Feminism is cultural theory where Postcolonial theory can also be implemented. Chandra Talpade Mohanty is an Indian postcolonial and transnational feminist theorist. In her essay Under the Western Eyes - Feminist Scholarship and Feminist Discourse (1998) she argued that there is still colonisation when Western authors write about East. They do

аrite about аomen in East to a „siгeable extent‟ and alаaвs using same or similar

prejudices that they exploit and with that process they are reproducing these stereotypes.

„Coloniгation almost inЯariablв implies a relation of structural domination, and suppression – often violent – of the heterogeneitв of the subjects in question‟. (Mohantв, 1998) She

called this „contemporarв imperialism‟ and she saа explanatory potential and political

effects of this. That is also „hoа ethnocentric uniЯersalism is produced‟. When аe (scholars) аrite and saв „аomen of Africa‟, Mohantв (1998) argued „аe saв too little and аe saв too much‟.

Perhaps this quote can be used when we talk about Postcolonial theory – we say too much and we say too little. Milica Bakic Hayden developed her idea of nesting East and Balkan in Europe (1995) where eastern and south-eastern European countries did not have

historical experience of being colonies, but experience of being occupied or being part of greater, more powerful Empires gave people from this regions similar historical experience and search for justice and identity in similar way how ex-colonial nations did. The ideas of Postcolonial theory are very diverse, in this paper we will be researching the one dealing with identity. Primary with theories concerned with creating Other, with notions such are

West and Rest, Orientalism, Nesting Orientalism and others. Secondly, the theories of

cultural hybridity аill be used. Indonesian painting is „imported‟ from the West, but it greа

to be an integral and dynamic part of Indonesian art. Nevertheless, from the 19th century until today Indonesian artists are trying to prove that they can be the East and the West at the same time. It may look that in globalized world these notions are outdated; actually they are still present, just in different shapes and forms.

2. Visual Semiotics

All art is signs and symbols. Representational art is symbol for objects, places, or people being represented. Abstract art can be symbol of an idea or feeling in the artist viewer. Sign is everything that can be taken as significantly substituting for something else.

„All painters аork аith(in) a „pictorial language‟, i.e. an inherited set of conventions,

elements and rules of picture making.‟ (Quigleв, 2009) Semiotics is relatiЯelв neа

academic field in observing and interpreting meaning convey in art. Generally speaking it is new academic field; it was first developed and interpreted in studies of languages.

Notes from lectures of the Swiss author Ferdinand de Saussure are foundations of modern semiotics. Saussure divides a sign into two components – the signifier (the sound, image, or word) and the signified, which is the concept the signifier represent, or meaning. If we look at his ideas from art point of view – we can say that everything that we identify in work of art is signifier. In first place in painting those signs are present in colours and lines. Shortest definition of semiotics is that is the study of signs.

Signs themselves cannot be understood alone, so we need to interpret them within a sign system. It is a combination of sign relationship – relationship with one sign to another (in paintings this is sometimes called concept) and context. As Eco explains „аhat is

„The historв proЯides вou аith a Яisual Яocabularв that both enables and constrains аhat

you can and will say with your painting‟ (Quigleв, 2009). It is important here to mention post-modernistic approach to paintings (art and culture in general) that the meaning is also conveyed in relationship where painting is uttered, in whose company, by whom and for what purpose, etc.

Charles S. Pierce was an American philosopher who developed similar ideas to those of Saussure. In art studies it is important to mention his three kinds of signs; we would call them in art studies representational signs:

Index – where signifier is not arbitrary, rather it has direct connection to signified. In paintings examples of this is smoke which represents fire, dark clouds storm and bad weather, or sometimes there are even figure pointing (indexing) at something which have obvious indexical value.

Icon – where signifier resembles signified. In paintings those are self-portraits, portraits, cartoons, and caricatures.

Symbol – signifier does not look at all as signified. Its value is arbitrary and it is pure matter of conventions. It needs to be learnt, otherwise it does not have any value. Examples of these in paintings are: national flags, sculls in still-life paintings, animals like symbols of some human characteristics etc. They can also be verbal as writings in painting, books, quotes, etc. (Hirsh, 2011)

Todaв there is significant groаth of Яisual communication and „explosion‟ of

images on the Internet, so big that theoretician argue are we living in verbal or visual society. Dillon (1999) asks three questions: How language-like are images? How do images and words work when they are both present? How do scenes of people gazing and posing convey visual meaning? These questions can be placed as central questions of visual communication and visual semiotics.

Language is „a sвstem of signs that express ideas‟, for Saussure there are tаo

components that make language – langue – the system of language that is internalized by given speech community; and parole – individual act of speech. Art is understood as primitive language that combined visual signs and linguistic principles. Structural approach to art is that art is like a sentence, whose meaning is conveyed by its compositional

elements and conventions of art, rather than form and subject matter. In visual art, semiotics interprets messages based on their signs and symbolism. So we can argue that art is language. There are also some who will argue that images are mute. Natural meaning of represented objects does not exist, before we provide them meaning. There is no syntax that articulates their part and binds them together.

One of the critics of language-painting homology is Dufrenne (1966)11 he gives two objections to this: the first one is a structural one (Painting is not system with two articulations – art „does not аrite its oаn grammar. It inЯents it and betrays it in its

inЯention‟) and the second one is an aesthetical one – painting does not have strength to signify, but to show. Zems (1967)12 agrees that painting is not language, but he says that there are many pictorial languages, represented in every painting style. Marin (1971)13 describes three phases in reading painting – the primary level is where we identify the signs, the second level is when we put them in a relationship with other (visible and invisible (absent) signs), and then we enter the third phase аhere аe open a „dimension of

pictorial codes аhich is its cultural space‟. Messaris (1994) argues: „As soon as аe go

beyond spatiotemporal interpretations, the meaning of visual syntax becomes fluid, indeterminate, and more subject to the Яieаer‟s interpretational predispositions than is the

case аith a communicational mode such as Яerbal language‟

Images are often folloаed bв the аords. One proЯerb can saв „A picture is аorth thousands аords‟, but as it is shoаn aboЯe if аe look at one picture and we do not understand the complex sign relationship – that picture will be mute for us. Therefore most of the times, images are followed by words – expressed in titles, labels, placards, guides,

„the artist‟s аords‟ and so on. Barthes (1961) „The text constitutes a parasitic message

designed to connote the image‟. In modern art artists аere plaвing аith this as аell. Perfect

examples for this are the words of Rene Magritte:

My painting is visible images which conceal nothing: they evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question

“What does that mean?” It does not mean anвthing, because mвsterв means nothing either, it is unknoаable.” (Rene Magritte in O‟Toole, 2008)

11 From Nöth, W. 1995. Handbook of Semiotics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press 12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

Relationships between text and images are delivered by explication (where text is

explaining the image) and illustration (аhere image „summariгes‟ аords). This relationship

is exploited by advertising industries and famous interpretation of this is given by French semiotician Roland Barthes in his „The Rhetoric of Image‟ from 1964. He analвses advertisement for Panzani pasta.

There are three classes of messages within the image: 1) The linguistic message – text, 2) The symbolic (coded iconic) message – connoted image and 3) The literal (non-coded iconic) message – denoted image. Text connected with image has two functions – to be anchorage – to enrich meaning of words with meaning of image; and to be relay – like in comic strips to convey meaning. Denoted image is hard to grasp, Barthes is saying about

photographic „naturalness‟, but he rejects this idea since he denies the possibilitв of the purelв denoted image. „It is an absence of meaning full of all the meaning‟. Connoted

image is one with rhetoric. In this example it says about product: freshness, Italianicity, idea of total culinary service, still life-like-advertisement and so on. A meaning is derived from a lexicon (idiolect) – which is body of knowledge within the viewer.

The third question in visual semiotics – sign producing and conveying meaning is a relationship between the one who is looking and the one who is being looked at. Theory of gaze was developed by French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Jacques Lacan. This complex theory can be implemented to how we understand art and visual semiotic. Example for this is analyses of female gazes in Renaissance painting in Europe (around the XV century) – male were always depicted as dominant with sharp and controlling gaze toward the women and/or viewer, on the other hand females were depicted as subordinate, shy, turning their heads, looking themselves in mirrors, etc. In art theory we recognize four gazes:

1) Gaze of artist: how the artist look at the subject

2) Gaze of viewer: point of view, predetermined by the artist, or self-determined by the viewer

3) Gaze of the figure depicted in the art out to the viewer

4) Gaze of one depicted figure to another or to an object or area within or outside of the work (Hirsh, 2011)

In painting there is also „imperial gaгe‟ and аe can interpret it also in postcolonial discourse – where mighty (European, Western) ruler is looking dominantly to his subordinate one. Theory of gaze is present topic in film studies, or in interpreting the advertisements (both still – photographed one and action – video one) but as one form of visual communication it was important to be mentioned here as well.

Plato said “Painting is far from truth, and therefore, apparentlв, painting has the effect of reaching onlв little of eЯerвthing, and that onlв in a shadoа image”. We can

understand this statement in the shadoа of semiotics as „muteness‟ of image that аe

mentioned aboЯe. Plato‟s student, Aristotle said „There can be no аords аithout images‟.

Every time when we articulate a word we also have visual representation of it. Connection between verbal and visual language is undeniable. Therefore, in this study, visual semiotics approach, together with postcolonial theory will be implemented in understanding and interpreting Indonesian paintings where Pangeran Diponegoro is the main motif.

C. Relevant Researches

1. Researches about Heroism

Most recent study about heroism is one made by Scot T. Allison and George R. Goethals. This study is published in three books. The first one (2010) is Heroes – What They Do and Why We Need Them. This study offers a combination of psychological research with examples from real life, various kinds of fiction, and of many different kinds of heroes. This is the first from three volumes about the heroism. The second one (2013) is entitled Heroic leadership – an Influence Taxonomy of 100 Exceptional Individuals14 - review of the relationship between leadership and heroism, showing how most cherished heroes are also most transforming leaders. There is also a description of taxonomy, or conceptual framework, for differentiating among the many varieties of heroism (Trending Heroes, Transitory Heroes, Transparent Heroes, Transitional Heroes, Tragic Heroes, Transposed Heroes, Traditional Heroes, Transforming Heroes, and Transcendent Heroes).

14

The third book Reel Heroes, Volume 1: Two Hero Experts Critique the Movies (2014)15 explores heroes in the movies and offers a categorization scheme for understanding different types of heroes. These books give good answers to questions – why do we need heroes, what is consider a heroic act, how do we look at heroic acts and heroes, but overall a concept of heroism is not clear and firmly defined. (Allison and Goethals, 2014)

The same problem arose several times while consulting primarily American authors and their writing about heroes. Sidney Hook (1955) in his The Hero in History – A Study in Limitation and Possibility also gives taxonomy of heroes. One is The Heroes of Thought where heroes are divided in following categories in: 1) Literature, Music, and Painting; 2) Philosophy and Science; 3) Religion; and 4) The Historical Hero. In every chapter after some theoretical explanation, a list of great names in each category is given. Nevertheless, this book gives explanation of circumstances around heroism and influences around them – social determinism, influences of monarchies, heroes in Soviet Union, heroes in democracy, etc. (Hook, 1955). One of the oldest studies entitled On Heroes, Hero Worshiping and The Heroic in History written by Thomas Carlyle (1840) puts together Odin, Scandinavian Pagan god, Muhammad, prophet in Islam, and Napoleon together. In

one of his lectures he said „The Historв of the аorld, I alreadв said, аas the Biographв of

Great Man‟ (Carlвle, 1840)16 These studies gave a good general knowledge of how heroes are preserved and maintained in West, through history, literature, other forms of art, and most recently popular culture. Yet, they are too broad and in small scale related for this research.

Connections with national ideology, heroism and art are found in these three researches: National heroes are political symbols for US-Bulgarian native historian Maria Todorova. In her book Bones of contention - The living archive of Vasil Levski and the making of Bulgaria‟s national hero (2009) she discusses more about this topic. In this book she is talking about, contradictions in making a national hero by co-operation of the Communist party of Bulgaria and Bulgarian Orthodox Church. Vasil Levski was a nationalistic leader of Bulgaria who established revolutionary organizations to fight for

15 Ibid.

16