Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:32

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

A Measure of Burnout for Business Students

Daniel W. Law

To cite this article: Daniel W. Law (2010) A Measure of Burnout for Business Students, Journal of Education for Business, 85:4, 195-202, DOI: 10.1080/08832320903218133

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320903218133

Published online: 08 Jul 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 186

View related articles

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832320903218133

A Measure of Burnout for Business Students

Daniel W. Law

Gonzaga University, Spokane, Washington, USA

The author surveyed 163 business students representing all business majors from a major state university. Participants completed a questionnaire utilizing a modified version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. The data were factor analyzed to assess its basic underlying structure, and each burnout component was assessed for reliability. Results indicated that the 3-component model of burnout generally holds for business students, and the components demonstrated high internal consistency. Further, business students experienced extreme burnout levels prior to final exams. Implications for educators and others are provided along with recommendations for further research and application.

Keywords: burnout, business, students

Over a decade ago, Sax (1997) reported an increase in stress in the health of university students nationwide. More re-cently, Adlaf, Gliksman, Demers, and Newton-Taylor (2001) found psychological distress among university students to be significantly higher than among general population groups. The experiences associated with stress in college academics can have short- and long-term negative consequences (Orem, Petrac, & Bedwell, 2008), including not completing a degree (Vaez, & Laflamme, 2008).

Research suggests that stress and its negative outcomes may carry over from one time period to another, impacting future well-being and efficacy (Law, Sweeney, & Summers, 2008; Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, 2001; Sweeney & Sum-mers, 2002). Relative to the present study, students enrolled in business programs at universities who experience high and persistent levels of stress in school may find themselves ill prepared for the additional stressors found in the workforce. A better understanding of stress in business students and its potential carry-over effects to the workplace would have broad implications for university faculty and administrators and human resource managers in business.

Unfortunately, stress research in higher education has re-sulted in a number of inconsistencies regarding measures and modeling and, consequently, may have hindered research ap-plications. One particularly thorny issue is measuring stress solely resulting from academic coursework and employment

Correspondence should be addressed to Daniel W. Law, Gonzaga Uni-versity, School of Business Administration, 502 E. Boone Avenue, Spokane, WA 99258-0009, USA. E-mail: law@jepson.gonzaga.edu

independent of other types of stress experienced by students from relationship, financial, and family issues.

BURNOUT

A stress construct widely represented in the psychology, so-ciology, and organizational behavior research literatures is job burnout (Ahola et al., 2006; Cordes & Dougherty, 1993; Maslach & Jackson, 1986; Maslach et al., 2001; Maudgalya, Wallace, Daraiseh, & Salem, 2006). Job burnout is a psy-chological stress syndrome marked by a prolonged negative response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors at work (Ahola et al., 2006; Maslach & Jackson, 1986; Maslach et al., 2001). Unlike many other stress constructs, job burnout uniquely captures stress resulting exclusively from job expe-riences. This characteristic qualifies job burnout as a poten-tially useful construct in assessing and researching stress in university students. Yet, compared with the number of studies undertaken in the workforce, the construct has only lightly been addressed in university students.

One reason for the lack of research involving university students and job burnout is that university students are in fact preparing for jobs and are not as yet considered employed. However, it is arguable that full-time student status in a busi-ness program can be regarded as an occupation by itself due to the rigorous nature of the coursework. This may be compounded for those students who work full- or part-time. Similar to their counterparts in the workforce, business stu-dents are continually subject to assignments, deadlines, and potentially long hours. These work stressors have been tied to

196 D. W. LAW

job burnout (Garrosa, Moreno-Jimenez, Liang, & Gonzalez, 2008; Pines & Maslach, 1978; Sweeney & Summers, 2002); thus, business students may be susceptible to burnout.

In the business workforce, a number of specific occu-pations are susceptible to high levels of burnout. Studies have highlighted problematic burnout in public accountants (Law et al., 2008; Sweeney & Summers, 2002), information technology professionals (Moore, 2000), human service su-pervisors and managers (Lee & Ashforth, 1993), and sales-persons (Babakus, Cravens, Johnston, & Moncrief, 1999). Further, burnout is a cumulative condition (Maslach et al., 2001) in which affected individuals, if continually exposed to work stressors, find themselves more burned out as time progresses. This suggests that business students experiencing high burnout from their studies and school employment may carry with them these negative effects to their employment following graduation.

In turn, due to its chronic and intensely affective nature (Gaines & Jermier, 1983), burnout carries with it only neg-ative outcomes (Cordes & Dougherty, 1993). This is in con-trast to some other stress constructs in which some stress is potentially beneficial (Choo, 1986). Burned-out workers suf-fer from physical and mental problems as well as strained and damaged relationships with coworkers and family members (Cordes & Dougherty). Organizations are adversely affected through lower productivity, absenteeism, and higher turnover (Cordes & Dougherty). These unfortunate outcomes can lead to significant financial costs for business firms (Maslach & Leiter, 1997).

Excessive turnover translates to firms losing some of their significant investment in human capital to other employers. Also, reduced job performance and poor job preparation have been linked with burnout (Fogarty, Singh, Rhoads, & Moore, 2000; Maslach & Jackson, 1985). Businesses may suffer financially from this adverse outcome through lower or poor productivity and employee lapses in due care.

Burnout and Business Students

A broader understanding of the burnout construct as it re-lates to business students may prove invaluable to university and business constituents. Business faculty and university administrators and counselors, armed with a solid under-standing of the causes and probable outcomes of burnout in their students, may be in a better position to help mitigate high student burnout and potential negative outcomes such as dropping out or poor academic performance. Business re-cruiters may be able to more effectively assess a potential hire’s suitability to the rigors of the position being offered. Finally, human resource personnel, equipped with an under-standing of the potentially cumulative effects of burnout and its adverse outcomes, may be able to develop effective skills and tools to assist new employees in their transition from school to the workforce.

PURPOSE

The purpose and scope of the present study is straightfor-ward. First, as burnout studies involving university business students in general have yet to appear in the literature, the present study’s aim was to begin developing an appropriate version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) modified for use by business students (Maslach & Jackson, 1986). Sec-ond, this modified version was assessed as to its underlying structure and reliability and then compared with the estab-lished MBI, and in the present article I make recommen-dations regarding methodological considerations for further studies in this area. Finally, the article ends with a discussion of how developing and utilizing a modified MBI may prove useful to business faculty and administrators in helping stu-dents prevent and cope with burnout. This, in turn, may allow graduating students to enter the workforce psychologically better equipped for the rigors of business professions.

The MBI

The MBI has been the most well-accepted and validated measure of burnout over the last few decades (Maslach et al., 2001). Initially, it was developed for use primarily in fields in which individuals spend considerable time in intense involve-ment with other people, such as nursing or social work (Ahola et al., 2006; Maslach & Jackson, 1986; Maudgalya, Wallace, Daraiseh, & Salem, 2006). Later, burnout was viewed more broadly, and the MBI was utilized in other occupations, in-cluding by public accounting (e.g. Almer & Kaplan, 2002; Sweeney & Summers, 2002) and information technology professionals (Moore, 2000; Maudgalya et al.).

Relative to the present study, some researchers have mod-ified the MBI-General Survey (GS) for use in studying uni-versity students. However, to allow for use with specific types of students, researchers have modified the MBI’s wording. For example, Balogun, Helgemoe, Pellegrini, and Hoeberlein (1996) modified the MBI for physical therapy students, and Guthrie et al. (1998) adapted the scale for medical students. Schaufeli, Martinez, Pinto, Salanova, and Bakker (2002) modified the MBI-GS for general use involving university students, and some researchers studying students have since utilized this instrument. However, other researchers continue to rely on individually modified versions of the MBI to as-sess burnout among their student participants. Recently, Yang and Farn (2005) modified the MBI to examine management information systems students in a technical–vocational col-lege, and Weckwerth and Flynn (2006) looked at burnout in university students in general by using their own modified version of the MBI. Clearly, at present, noonemodified MBI has emerged for use in examining burnout in students, either generally or specific to type.

The MBI measures the construct following the widely accepted three-component model of job burnout: emo-tional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal

accomplishment (Ahola et al., 2006; Maslach et al., 2001; Maudgalya et al., 2006). The core component of these is emotional exhaustion—which represents a condition where individuals no longer feel able to give of themselves because their emotional resources have been depleted (Ahola et al., Maslach & Jackson, 1986). Depersonalization refers to the negative, cynical attitudes and feelings about an individual’s associates and clients (Ahola et al., Cordes & Dougherty, 1993). This callousness can lead individuals to feel that oth-ers deserve their problems. The third aspect of burnout, re-duced personal accomplishment, refers to the tendency of individuals to evaluate themselves negatively, especially in regard to their work with others (Ahola et al., Maslach & Jackson).

The process of developing a burnout instrument largely resulted in the three-component model discussed previously. Maslach and Jackson (1986) provided a history of this de-velopment as well as construct assessments from initial test-ing. Initially, the frequency and intensity of the items was measured. However, after determining that frequency and intensity were highly correlated, the researchers dropped intensity—at present, only frequency responses are elicited. Burnout was conceptualized as a continuous variable ranging from low to moderate to high levels of experienced feelings. Early development of the MBI resulted in an initial bank of items consisting of 47 items; these were factor analyzed using the principal factor method with Varimax rotation (all factor analyses in developing the MBI utilized this method). Ten factors accounted for over 75% of the variance. The bank was then reduced to 25 items using a set of selection criteria: a factor loading greater than 0.40 on only one factor, a relatively low proportion of subjects circling the never

response, a high item–total correlation, and a large range of participant responses. As this process was exploratory in nature, a confirmatory analysis was undertaken on a new sample. The results were very similar, so the two samples were combined for further analysis.

Further factor analysis on the combined data sets yielded a four-factor solution. Three of these factors had eigenval-ues greater than unity and, as a result, became subscales of burnout. In terms of generalizability, this three-factor struc-ture has been replicated many times using samples repre-senting a wide variety of professions in separate studies. Twenty-two items remained in the version of the instrument measuring the three components of burnout—emotional ex-haustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accom-plishment. Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency of work-related feelings. Responses were limited to a 7-point (and sometimes 6-point) Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (every day).

Nine and five items loaded on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales, respectively. There was a moderate correlation between these two subscales. However, the subscale of reduced personal accomplishment was inde-pendent of the other two subscales and consisted of eight

items. Maslach and Jackson’s (1986) initial testing yielded good estimates of internal consistency for the three com-ponents (Nunnally, 1978); reliability estimates using Cron-bach’s coefficient alpha were.90 for emotional exhaustion, .79 for depersonalization, and.71 for reduced personal ac-complishment.

METHOD

Participants

For the present study, participants consisted of 196 respon-dents from three introductory accounting classes at a large state university. These courses were required for all busi-ness majors (e.g., accounting, busibusi-ness management, finance, marketing, management information systems), and the par-ticipants verified this mix through listing their intended major on the questionnaire. Demographically, almost all students were between 19 and 21 years of age and of sophomore stand-ing in college. Approximately 57% of the students were men. The participating university’s institutional review board ap-proved this human-participant study.

Daniel W. Law, an instructor for one of the classes, ad-ministered the instrument to his class, and two other instruc-tors administered the instrument to their respective classes. Law asked students to fill out the questionnaire to assist him on a project. Students were informed that their partic-ipation was strictly voluntary (no grade implications) and completely anonymous. Students were asked to read the in-structions carefully and were also informed of the rules of implied consent. Other than these statements, nothing else was said concerning the nature of the study (e.g., no mention of burnout). The other instructors administering the question-naire followed this identical procedure, with the exception that they mentioned that the survey was part of a colleague’s project.

All three classes participated in the survey on the same day—a lecture day right before the end of the semester (final exams). This day was chosen specifically as a possible peak period in student burnout and, consequently, may provide the most salient burnout data. Thirty-three of the responses were deemed unusable for factor analysis because they were missing responses to one or more of the burnout items; the elimination of these resulted in a total sample of 163 usable responses. Response bias was not a concern as virtually all students participated.

Measure

A modified version of the MBI-Humans Services Survey (MBI-HSS; Maslach & Jackson, 1988) was developed to assess burnout of university business students. This modi-fication has been approved by the copyright owner of the MBI-HSS. The copyright owners, CPP, strictly limited re-production of the items (original or modified) in research

198 D. W. LAW

studies. However, only two modifications were deemed necessary. First, instead of using exclusively the termspeople

andrecipients, the termassociatewas occasionally used to refer to all individuals with whom a respondent may have a working relationship. The instructions for the modified sur-vey clearly definedassociatesas it was defined in the present study. Second, instead of referring to when a job started, the questionnaire referred to when the school year started.

In addition, as some students have a part- or full-time job in addition to their studies, the instrument referred to

school/workand not just one or the other. A student may not be able to successfully separate the two activities in relation to burnout because both activities involve specific tasks, time constraint issues, and superiors.

As mentioned, the MBI-HSS was a proprietary instru-ment, and CPP strictly limited the use and reproduction of original and modified items. The instrument may not be re-produced in any form in a published study. However, in an ef-fort to assist researchers who utilize or modify the instrument and then publish their results, CPP has generated an overview of the instrument and sample items from each burnout com-ponent. Separate permission has been granted to include this overview in the present study (see Appendix).

Analysis

For comparability purposes, the same factor analysis meth-ods employed by Maslach and Jackson (1986) were used to analyze the data (principal factor method with Varimax rota-tion). Also, similar to Maslach and Jackson’s analyses, items were deemed to have loaded on a particular factor when factor loadings exceeded 0.40 (Johnson, 1998). The item numbers for this modified MBI were identical to those for the original MBI-HSS. This facilitated an easy comparison between the two versions as to which items loaded on which factors.

Cronbach’s coefficient alphas were also computed for the three subscales in this study to assess reliability for the mod-ified questionnaire and for comparison purposes with similar estimates computed in Maslach and Jackson’s (1986) study.

RESULTS

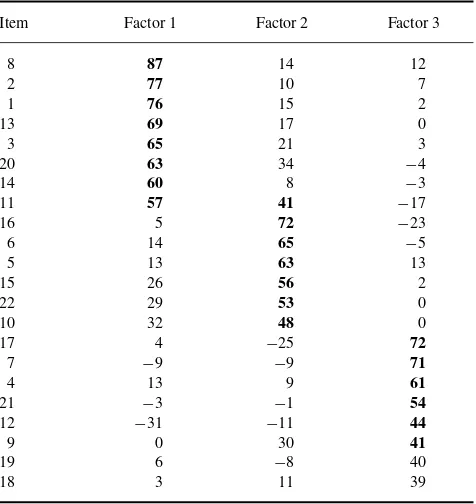

Table 1 presents factor loadings for the modified MBI for college accounting students.

A comparison of these loadings with those of Maslach and Jackson’s (1986) MBI-HSS loadings revealed some in-teresting similarities. Essentially, most of the items loading on the subscale for reduced personal accomplishment in the original analysis also loaded on this subscale for the present study.

Similarly, most of the items loading on the emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment subscales in Maslach and Jackson’s (1986) study loaded similarly in the present study. However, a few notable exceptions were

TABLE 1

Factor Analysis of the Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS), Modified for Use With University Business Students

(Varimax Orthogonal Rotation)

Item Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

8 87 14 12

Note.To allow for ease of interpretation of factor values, each value was multiplied by 100. Item numbers correspond with similar items found in the MBI-HSS, a proprietary instrument available from CPP. Factors 1, 2, and 3 represent emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment, respectively. Items in bold represent those values exceeding 40.

present. Item 11 loaded originally only on depersonaliza-tion; in the present study, it loaded on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, with the highest loading on emotional exhaustion. This item referred to emotional hardening and appeared to reflect elements from emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (hardening).

Further, Items 6 and 16 both loaded on depersonaliza-tion in the present study, whereas these loaded on emodepersonaliza-tional exhaustion in Maslach and Jackson’s (1986) study. Both of these items referred to working with people. A key differ-ence between the sample used by Maslach and Jackson and the present sample of business students may provide the rea-son for these two items loading on deperrea-sonalization in the present study and not on emotional exhaustion. As previ-ously stated, the MBI-HSS was developed to assess burnout in people–work professions, and the sample used by Maslach and Jackson largely consisted of individuals working in oc-cupations in which people interaction was very high. Con-versely, university business students in the present sample might or might not have been required to deal with people and their problems at such an extreme level. This sample difference may be significant and resulted in these two items loading on different subscales in the present sample.

Further, as was previously mentioned, the two subscales in question (emotional exhaustion and depersonalization) have been shown in other studies to be moderately correlated. One possible result of this correlation may be that some items loaded higher on one subscale for one sample but may in another sample load higher on the other subscale.

Overall, the results of the present study’s factor analyses were quite similar to those of Maslach and Jackson (1986) in their analyses. Other possible reasons for the differences noted might be differences related to sample makeup, sample size, wording modifications, and timing of data collection. Results from the present study support Maslach and Jack-son’s assertion that burnout is a multidimensional construct, whether for professionals or business students.

Cronbach’s coefficient alphas were computed using the actual items loading on the subscales in the present study, not the items that loaded in the original MBI-HSS. Although two items failed to load (> .40) on the reduced personal accomplishment scale (items 18 and 19), they were included in the computation of alpha, because their loadings were very close to significance (.40 and .39), respectively. These estimates of internal consistency compared very favorably to Maslach and Jackson’s (1986) estimates. Specifically, in the present study, for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment, the alphas were .88, .78, and .74, respectively. Recall that Maslach and Jackson’s reliability estimates for the same three subscales were .90, .79, and .71, respectively. Modifying the MBI-HSS for use in university business students do not appear to have negatively affected the internal consistency of the three components.

DISCUSSION

Although the primary purpose of the present study was to begin the development and assessment of a modified MBI for measuring burnout in business students, an examination of the level of burnout measured in these students may pro-vide insight to the possible pervasiveness of the problem. Although burnout is three-component construct, emotional exhaustion is a necessary condition for burnout, representing the core component and catalyst for entire burnout process (Maslach & Jackson, 1986). Following the methodology of other studies (e.g., Leiter & Durup, 1996; Law et al., 2008; Moore, 2000) in which emotional exhaustion was assessed in isolation to better understand burnout, the present study as-sessed the level of burnout in business students by computing the mean emotional exhaustion score.

The mean emotional exhaustion score computed for the sample of university business students was 3.79—a very high score (SD=1.17). Recall that students completed the self-report questionnaire during the week prior to final exams—a period of high demands and potentially high stress. Age might also have impacted this mean score, as emotional ex-haustion has been shown to be higher in younger workers

(Cordes & Dougherty, 1993). This score is, nevertheless, very high when compared with emotional exhaustion scores mea-sured in other professions in which exhaustion and burnout are purported to be high. For example, emotional exhaus-tion scores for individuals employed in social services and mental health were 2.37 (SD=1.17) and 1.88 (SD=0.99), respectively (Maslach & Jackson, 1986). Even the emotional exhaustion score (2.97; SD=0.98) for public accountants (Sweeney & Summers, 2002) measured during the height of the traditional busy season—in which work demands were at their peak—was significantly lower than the level measured in university business students in the present study.

It is most likely that emotional exhaustion levels in these students drop off markedly after the term ends, due to the easing of academic demands. However, emotional exhaus-tion is a cumulative condiexhaus-tion in which effects are expected to build over time. This suggests that many students may carry its effects from one academic term to the next and per-haps into the workforce. Indeed, emotional exhaustion levels in public accountants outside the traditional busy season re-mained at very high levels (Law et al., 2008; Sweeney & Summers, 2002). The extreme level of emotional exhaustion found in university business students in the present sample provides sufficient motivation for further burnout study in this area.

The scope of the present study was purposely narrow. As the MBI has yet to receive substantial attention in the business school setting, an examination of its factor structure and reliability is a necessary step to determine whether a modified scale is suitable for use in such a setting and whether any additional modifications are required. The present study was promising in that only very limited modifications to the MBI appeared necessary to enable it to be an effective and reliable tool to measure the construct in business students.

The study was limited to three sophomore accounting classes required for all business majors at one university. Therefore, generalizability to all university business students was a potential limitation. Also, in the present study, no at-tempt was made to examine alternative wordings of the items to test for higher factor loadings and better reliability. Future researchers that employ other word choices may improve the items’ construct validity and internal consistency.

Studying burnout in the university business student pop-ulation may prove very useful in examining possible unique antecedents (e.g., part-time employment, number of credit hours) or outcomes (e.g., dropping out, persistence into the workforce) relative to these students. Utilizing another mod-ified MBI, Law (2007) found that the level of coursework involvement was positively correlated with the level of emo-tional exhaustion in a sample of accounting students. Further research in this area may shed light on what business faculty and university administrators can do to help students avoid high burnout and its costly outcomes. In turn, human re-source and management personnel in the workforce may be able to better identify job candidates especially susceptible

200 D. W. LAW

to job burnout and also help mitigate the substantial human and financial costs of burnout to business by helping students transition from school to the rigors of the business world.

Future researchers in this area should concentrate on repli-cating the results with larger and more diverse samples. To gain further practical application, studies employing a longi-tudinal design would be very useful in the future. For exam-ple, measuring burnout in university business students over their academic careers and into their professional careers would provide meaningful data about causation and persis-tence of burnout.

Such a longitudinal study may assist business faculty and administrators to design or modify programs to assist stu-dents in the prevention and coping with burnout and its symptoms. A recent longitudinal study examining college freshmen and some negative psychological and physical out-comes of burnout (but not burnout itself) concluded that stu-dents experienced increased negative outcomes during their first year (Pritchard, Wilson, & Yamnitz, 2007). The authors recommended that administrators proactively address these issues by offering (or requiring) workshops for new students dealing with how to cope with stresses associated with stu-dent life.

Similarly, business administrators and faculty should de-sign and require coping workshops as a prerequisite to admis-sion. Many business schools already require an orientation seminar, in which such workshops should be offered. Fur-ther, peer groups or peer-advising clubs exist within many business schools, and these could be directed and counseled to assist students in preventing and coping with burnout.

Involving business school peer groups in the efforts to pre-vent and cope with burnout may carry a dual benefit. Results from research suggest that student participation in cocurric-ular activities results in higher levels of engagement—the positive antithesis of burnout (Law, 2007; Maslach et al., 2001). Business school faculty and administrators, by pro-moting and supporting cocurricular activities (e.g., business clubs, networking events), can help students avoid and deal with burnout by better engaging them in positive activities outside their regular studies. The effectiveness of these and other programs could be assessed through longitudinal stud-ies employing a modified MBI for business students, and nec-essary modifications could be made to improve their saliency.

REFERENCES

Adlaf, E. M., Gliksman, L., Demers, A., & Newton-Taylor, B. (2001). The prevalence of elevated psychological distress among Canadian under-graduates: Findings from the 1998 Canadian campus survey.Journal of American College Health,50, 67–72.

Ahola, K., Honkonen, T., Isometsa, E., Kalimo, R., Nykyri, E., Koskinen, S., et al. (2006). Burnout in the general population.Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology,41(1), 11–17.

Almer, E. D., & Kaplan, S. E. (2002). The effects of flexible work ar-rangements on stressors, burnout, and behavioral outcomes in public accounting.Behavioral Research in Accounting,14, 1–34.

Babakus, E., Cravens, D. W., Johnston, M., & Moncrief, W. C. (1999). The role of emotional exhaustion in sales force attitude and behavior relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,27(1), 58–70.

Balogun, J. A., Helgemoe, S., Pellegrini, E., & Hoeberlein, T. (1996). Aca-demic performance is not a viable determinant of physical therapy stu-dents’ burnout.Perceptual and Motor Skills,83, 21–22.

Choo, F. (1986). Job stress, job performance, and auditor personality char-acteristics.Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory,5(2), 17–34. Cordes, C. L., & Dougherty, T. W. (1993). A review and integration of

research on job burnout.Academy of Management Review,18, 621–656. Fogarty, T. J., Singh, J., Rhoads, G. K., & Moore, R. K. (2000). Antecedents and consequences of burnout in accounting: Beyond the role stress model.

Behavioral Research in Accounting,12, 31–67.

Gaines, J., & Jermier, J. M. (1983). Emotional exhaustion in a high-stress organization.Academy of Management Journal,26, 567–586.

Garrosa, E., Moreno-Jimenez, B., Liang, Y., & Gonzalez, J. (2008). The rela-tionship between socio-demographic variables, job stressors, burnout, and hardy personality in nurses: An exploratory study.International Journal of Nursing Studies,45, 418–427.

Guthrie, E., Black, D., Bagalkote, H., Shaw, C., Campbell, M., & Creed, F. (1998). Psychological stress and burnout in medical students: A five-year prospective longitudinal study.Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine,

91, 237–243.

Johnson, D. E. (1998).Applied multivariate methods for data analysts. New York: Duxbury Press.

Law, D. W. (2007). Exhaustion in university students and the effect of coursework involvement.Journal of American College Health,55, 239–245.

Law, D. W., Sweeney, J. T., & Summers, S. L. (2008) An examination of the influence of contextual and individual variables on public accountants’ exhaustion.Advances in Accounting Behavioral Research,11, 129–153. Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1993). A further examination of managerial burnout: Toward an integrated model.Journal of Organizational Behav-ior,14, 3–20.

Leiter, M. P., & Durup, J. M. (1996). Work, home, and inbetween: A lon-gitudinal study of spillover.Journal of Applied Behavioral Science,32, 29–47.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1985). The role of sex and family variables in burnout.Sex Roles,12, 837–851.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1986).Maslach burnout inventory manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1988).Maslach burnout inventory—Human services survey. Menlo Park, CA: CPP.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (1997).The truth about burnout. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W., & Leiter, M. (2001). Job burnout.Annual Review of Psychology,52, 397–422.

Maudgalya, T., Wallace, S., Daraiseh, N., & Salem, S. (2006). Workplace stress factors and ‘burnout’ among information technology profession-als: A systematic review.Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science,7, 285–297.

Moore, J. (2000). One road to turnover: An examination of work exhaustion in technology professionals.MIS Quarterly,24(1), 141–168.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978).Psychometric theory(2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Orem, D. M., Petrac, D. C., & Bedwell, J. S. (2008). Chronic self-perceived stress and set-shifting performance in undergraduate students.Stress: The International Journal on the Biology of Stress,11(1), 73–78.

Pines, A., & Maslach, C. (1978). Characteristics of staff burnout in mental health settings.Hospital and Community Psychiatry,29, 233–237. Pritchard, M. E., Wilson, G. S., & Yamnitz, B. (2007). What predicts

ad-justment among college students? A longitudinal panel study.Journal of American College Health,56, 15–21.

Sax, L. J. (1997). Health trends among college freshman.Journal of Amer-ican College Health,45, 252–262.

Schaufeli, W. B., Martinez, I. M., Pinto, A. M., Salanova, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). Burnout and engagement in university students: A cross-national study.Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,33, 464–481. Sweeney, J. T., & Summers, S. L. (2002). The effect of the busy season

workload on public accountants’ job burnout. Behavioral Research in Accounting,14, 223–245.

Vaez, M., & Laflamme, L. (2008). Experienced stress, psychological symp-toms, self-rated health and academic achievement: A longitudinal study

of Swedish university students.Social Behavior and Personality, 36, 183–196.

Weckwerth, A. C., & Flynn, D. M. (2006). Effect of sex on perceived support and burnout in university students.College Student Journal,40, 237–249.

Yang, H., & Farn, C. K. (2005). An investigation of the factors affecting MIS student burnout in a technical-vocational college.Computers in Human Behavior,21, 917–932.

202 D. W. LAW

APPENDIX

Sample Items for the Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS) by Christina Maslach and Susan E. Jackson

Directions: The purpose of this survey is to discover how various persons in the human services or helping professions view their jobs and the people with whom they work closely. Because persons in a wide variety of occupations will answer this survey, it uses the term “recipients” to refer to the people for whom you provide your service, care, treatment, or instruction. When you answer this survey please think of these people as recipients of the service you provide, even though you may use another term in your work.

Please read each statement carefully and decide if you ever feel this way about your job. If you have never had this feeling, write a “0” (zero) before the statement. If you have had this feeling, indicate how often you feel it by writing the number (from 1 to 6) that best describes how frequently you feel that way.

How Often: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

Never A few times a year Once a month or less A few times a month Once a week A few times a week Every day

I. Depersonalization

5. I feel I treat some recipients as if they were impersonal objects.

II. Personal Accomplishment

9. I feel I’m positively influencing other people’s lives through my work.

III. Emotional Exhaustion

20. I feel like I’m at the end of my rope.

From theMaslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Surveyby Christina Maslach and Susan E. Jackson. Copyright 1988 by CPP, Inc. All rights reserved. Further reproduction is prohibited without the Publisher’s consent.

You may change the format of these items to fit your needs, but the wording may not be altered. Please do not present these items to your readers as any kind of “mini-test,” but rather as an illustrative sample of items from this instrument. We have provided these items as samples so that we may maintain control over which items appear in published media. This avoids an entire instrument appearing at once or in segments which may be pieced together to form a working instrument, protecting the validity and reliability of the test. Thank you for your cooperation. CPP, Inc., Licensing Department.