POLICING OUR CAMPUSES: A NATIONAL

REVIEW OF STATUTES

Max L. Bromley

University of South Florida, TampaINTRODUCTION

The Problem of Campus Crime: Yesterday and Today

College campus crime and associated problems have received considerable attention from the media, courts and legislatures during the last ten years. Prior to the 1980s, it seems that most college campuses were relatively free from serious crimes with the exception of the violence which occurred on campus during the Vietnam War era. Education historians such as Hollis (1951), Humphrey (1976), McGrane (1963) and Wertenbacker (1946) have all described the relatively minor crimes that characterized college campuses in the past. In contrast, researchers such as Bromley and Territo (1990), Nichols (1986), Siegal and Raymond (1992) and Smith (1988) describe a greater frequency of serious crimes being committed on campus today. As Bordner and Petersen (1983:38) have stated, “the university is like a city as far as crime in concerned”.

Certainly, the media have focused a significant amount of attention on campus crime issues within the last decade. Articles appearing in USA Today(Ordovensky, 1990), the Chronicle of Higher Education(Lederman, 1993, 1994), the New York Timesmagazine, (Mathews, 1993) and the New York Times(Castelli, 1990) are examples of lengthy feature stories that have focused on crime on campus or security programs being developed in response to those crimes.

themselves in the administration of higher education, this is no longer the case according to Kaplin (1990). Since the mid-1970s the courts, state legislatures and Congress have become active in responding to campus crime issues. For example, according to Smith (1988), campus crime victim lawsuits against colleges have become commonplace. In well reported cases such as Duarte v. State [1979]; Peterson v. San Francisco Community College District, 1984; Miller v. State of New York [1984]; and Mullins v. Pine Manor College[1983], plaintiffs were successful in winning crime liability claims filed against post-secondary institutions. Some students who have been the victims of off-campus crime have also tried to sue their institutions. Case examples include: Donnell v. California Western School of Law [1988], Whitlock v. University of Denver (1987), andHartman v. Bethany College[1991]. While the plaintiffs in these cases were not successful, they are indicative of the current trend in lawsuits against institutions of higher education in the area of safety and security. As a result of these and other lawsuits, colleges and universities now must not only acknowledge the existence of campus crime, but must also take proactive measures to prevent incidents from occurring or suffer the potential monetary consequences.

Following the murder and rape, in 1986, of Jeanne Clery at Lehigh University (Pennsylvania), her parents were successful in winning a lawsuit against the university. The family also engaged in a highly publicized campaign seeking the passage of legislation that would require post-secondary institutions to make public their campus crime statistics. Subsequently, the state of Pennsylvania, in 1988, passed the first campus crime “Right to Know Law”. According to Griffaton (1995), 14 other states have since passed similar laws increasing the public’s awareness of the nature and extent of campus crime. Many of these states also passed legislation requiring educational institutions to enhance their security policies and programs. Congress has also passed the Student Right to Know and Campus Security Act of 1990, which requires campus decision makers to make public security features and policies as well as crime data.

In response to the problem of serious campus crime, the role of campus police has evolved over the last two decades to the extent that many institutions are now served by full-service campus police departments (Nichols, 1986). Historically, parking enforcement at many campuses has been a responsibility of the campus police department. In addition, many of today’s larger urban campuses have significant traffic congestion problems. Currently, full-service campus police agencies must be prepared to deal with more serious traffic problems (including accident-related injuries) and implement drunk driving enforcement programs. Bordner and Petersen (1983) have also noted that many police officers at public institutions have the same responsibilities as their city or county law enforcement counterparts. Atwell (1988:2) notes that “we should be alert to the public’s expectation that campus police will treat crimes of all types in ways very nearly identical to municipal law enforcement agencies”.

Researchers such as Sloan (1992) and Peak (1988, 1995), have conducted descriptive studies in order to better understand the organizational similarities between campus and local police departments. However, relatively little has been done to examine the state statutes which provide the basis of campus police power and authority. In order to better understand the extent to which campus police agencies are able to deal with serious crime problems, it is appropriate to further review the source of their police powers. The work of Gelber (1972) remains the only extensive examination of this issue. The purpose of the present study is to provide a more current and detailed analysis of campus police statutes throughout the country.

Three general questions guided this inquiry:

(1) How have the states responded statutorily in their efforts to provide professional campus police/security on colleges and universities?

(2) What are the common elements of current campus police statutes?

(3) What trends can be described with respect to the current statutes?

METHODOLOGY

sent to members of the International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrations in each state to verify that they were current. Follow-up phone calls were made to these individuals as necessary. Finally, assistance in the verification process was obtained from the National Association of College and University Attorneys. The data and subsequent analyses that follow do not reflect laws passed or amendments occurring after October 1994.

RESULTS

The results of this study provide a profile of state laws pertaining to campus police.

Types of Institutions Covered by Statute

Forty-four states have statutes which make specific reference to campus policing, with the vast majority relating to public institutions only. Two states, North Carolina and Texas, have separate statutes granting police powers at public and private institutions of higher education. In contrast, both public and private institutions are granted police authority by the same statute in four states (Indiana, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Virginia). Eight states provide police powers for personnel working at community colleges (Florida, Indiana, Missouri, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and Tennessee).

Location of Statute

Given the rather unique nature of university communities, it was interesting to determine where the laws describing campus police were located within various statutory categories. For example, of the statutes that were found that granted campus police authority, the vast majority are located in a category related to education. However, Arkansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Oklahoma, Wyoming and Texas locate campus police authority outside of the area of education.

“special police officer” status to officers at educational institutions as well as hospitals.

Typical Sections/Elements within Campus Police Statutes

The present study did not reveal a single-model concept with respect to elements typically found within campus police statutes. However, the following sections are often found: appointing authority, jurisdiction, police powers and police officer qualifications/training requirements. Examples of the variation in the content of these sections is described in the section that follows.

APPOINTING AUTHORITY

Typically, the institution’s chief executive officer (president or chancellor) or the governing board (regents, trustees, etc.) is designated as the appointing authority for campus police. Exceptions to this trend are found only in Massachusetts, New Jersey and Rhode Island. The Colonel of State Police in Massachusetts and the Superintendents of State Police in New Jersey and Rhode Island are identified in their respective statutes as having responsibility as appointing authority for campus police officers. For example, the Massachusetts statute states: “The colonel may, upon such reasonable terms and conditions as may be prescribed by him, at the request of an officer of a college, university, other educational institution or hospital licensed pursuant to section fifty-one of chapter one hundred and eleven appoint employees of such college, university, other educational institution or hospital as special state police officers. Such special state police officers shall serve for three years, subject to removal by the colonel and they shall have the same power to make arrests as regular police officers for any criminal offense committed in or upon lands or structures owned, used or occupied by such college, university, or other institution or hospital”.

Jurisdiction

is no less important, but sometimes it is more difficult. For example, cities and counties are usually well-defined political entities that are confined to specific contiguous geographic parameters. Thus, the jurisdiction of the police agencies in these communities is fairly straightforward.

By contrast, the boundaries of many of today’s college campuses are not easily defined. For example, an institution may own or lease properties located apart from what may be viewed as the “main campus” boundaries. Also, the extent to which state legislatures are willing to statutorily authorize campus police to exercise police powers away from campus grounds was of interest in the current inquiry. Jurisdictions were characterized as either “limited” or “extended”. A limited jurisdiction was defined as one wherein officers were limited to campus property or properties specifically under the control of the institution. A jurisdiction was defined as extended if the police were able to exercise their authority beyond campus properties.

Statutes in 21 states were classified as limited and statutes in 22 states categorized as extended. The statute in one state made no mention of jurisdiction.

An example of a limited statute is Florida’s which states: “The university police are hereby declared to be law enforcement officers of the state and conservators of peace with the right to arrest, in accordance with the laws of the state, any person for violation of state law or applicable county or city ordinance when such violations occur on any property or facilities which are under the guidance, supervision, regulation, or control of the state university system”.

Georgia provides an example of an extended jurisdiction statute which reads as follows: “Campus means the grounds and buildings owned or occupied by a college or university or the grounds and buildings of a school or training facility operated by or under the authority of the State Board of Education. The term campus shall also include any public or private property within 500 yards of the property of an educational facility and one quarter of a mile of any public street or public sidewalk connecting different buildings of the same educational facility when the property or buildings of the educational facility are located within any county of this state having a population of 400,000 or more”.

Police Powers

Another important element dealt with in state statutes concerns the nature and scope of police powers granted to campus officers. More specifically, do campus police officers possess the same law enforcement powers, including arrest, as those granted to law enforcement officers of local government? In all states that had enacted a campus police statute, campus police had virtually the same powers as their municipal counterparts.

Following are three examples of statutory language that describe the similarity between campus police power and that of local law enforcement. First, in Maryland law, “Officers (referring to campus police) shall have all the powers of peace and police officers in Maryland”. In the Michigan law, “Public safety officers shall be considered peace officers of the state and so have the authority of police officers”. Finally, in Oklahoma, “Campus police officers commissioned pursuant to this act have the same powers, liabilities and immunities as sheriffs or police officers within their jurisdiction”.

Police Officer Qualifications and Training

Other Statutory Features

While not necessarily present in most statutes, several specific features were found in many of the state laws authorizing campus police. Several examples are described in the following sections of this paper.

Hot Pursuit

Authority for campus police to continue the pursuit off-campus of persons suspected of committing campus crimes was clearly granted in nine statutes. For example, in Louisiana, “In the discharge of their duties on campus or while in hot pursuit, on or off the campus, each university or college police officer may exercise the power of arrest”.

In the Maryland law, “…the police officer may not exercise these powers on any other property unless: engaged in a fresh pursuit of a suspected offender”. Finally, the language in Nevada’s statute allows campus officers to exercise their power and authority, “when in hot pursuit of a violator leaving such a campus or area”.

Mutual Aid Agreements

Today, many local police departments and sheriff’s offices have entered into mutual aid or interlocal agreements with neighboring law enforcement agencies. These agreements allow departments to share enforcement resources in times of need. Given the fact that many campus police departments may be dependent on external law enforcement resources for support, the current study also examined “mutual aid” language in the campus police statutes.

Specific reference was made to campus/local police agreements in only nine statutes. In some statutes, the emphasis was placed on campus police being able to expand their jurisdiction beyond institutional boundaries through agreements with local law enforcement agencies. For example, in Indiana, “...additional jurisdiction may be granted by agreement with the Chief of Police of the municipality or Sheriff of the county or the appropriate law enforcement agency where the property is located, dependent on the jurisdiction involved”.

those duties conferred within this section within the municipality for the limited purpose of aiding local authorities in emergency situations”.

External Law Enforcement Agency Authority on Campus

As reported in an earlier section, campus police statutes generally provide campus officers with the same powers of arrest and authority granted to local police and sheriffs. The current study found that ten of the statutes included language specifying that local law enforcement authorities could exercise their police powers on college or university campuses. Apparently, the legislatures of these states wanted to assure local law enforcement officials that campuses would not be exempt from local police authority.

As noted in Delaware’s statute, “Provisions of this statute do not reduce, nor restrict the jurisdiction of other duly appointed peace officers who are empowered to enforce federal or state laws or applicable county or city ordinances on the property of the University of Delaware”. Note that this statute also includes a reference to federal law enforcement.

The Rhode Island statute uses somewhat different terminology to achieve the same end: “Appointment of special officers (e.g., campus police) hereunder shall in no way limit the powers, authority and responsibility of state police and police of the various cities and towns to enforce state law and municipal ordinances on property owned by the educational institutions”. The Arkansas statute states that, “none of the present jurisdictional powers or responsibility of the county sheriffs or city police over the land or property of institutions or persons on the land shall be ceded to the security officers of state institutions. The appointment or designation of institutional security officers shall not be deemed to supersede, in any way, the authority of the state police or the county sheriffs, or that of the peace officers of the jurisdiction within which the institution, or portions of it, shall be located”.

Bonding and Equipment Requirements

Fifteen statutes listed specific requirements for campus police officers such as bonding or made mention of specifications for campus police with respect to uniforms, badges or vehicles to be used.

office, except that no such badge shall be required to be worn by any plain clothes investigator or departmental administrator, but any such person shall present proper credentials and identification when required in the performance of such officer’s duties”.

The New Jersey campus police statute requires “Each policeman when on duty, except when employed as a detective to wear in plain view a name plate and a metallic shield or device with the word ‘Police’ and the name or style of the institution for which he is appointed inscribed thereon”.

In the Louisiana law, a bond requirement is specified requiring that “…each such police officer shall execute a bond in the amount of $10,000 in the favor of the state, for the faithful performance of his duties. The premium on the bond shall be paid by the employing institution”.

The campus police statute for Kentucky mentions emergency vehicles. “Vehicles used for emergency purposes by the safety and security department of a public institution of higher education shall be considered as emergency vehicles and shall be equipped with blue lights and sirens and shall be operated in conformance with the requirements of KRS Chapter 189”.

Rule Enforcement by Campus Police

While the present study focused on specific, traditional police powers and responsibilities granted through campus police statutes, additional regulatory and enforcement requirements were also found in several laws. These noted specific tasks required of some campus police officers that may not have a parallel in local law enforcement agencies. For example, several statutes specify that campus police are responsible for the enforcement of institutional rules or regulations in addition to criminal law enforcement.

In North Dakota, the statute states, “…the board of higher education shall provide for the administration and enforcement of its regulations and may authorize the use of the special policemen to assist in enforcing the regulations in the law on the campus of a college or university…”. The Utah campus police statute states, “Members of the police or security department of any college or university also have the power to enforce all the rules and regulations promulgated by the Board of Regents as related to the institution”.

police powers necessary to enforce all state laws as well as rules and regulations of the Board of Regents and the Board of Trustees”.

Miscellaneous Features of Campus Police Statutes

The current study revealed a number of miscellaneous features found in several state statutes that provide insight into the unique role played by members of campus law enforcement departments. For example, the statute in Alabama includes a section that prohibits campus police officers from entering a classroom for the purpose of enforcing traffic or parking citations.

The campus police statute in Illinois directs the state to provide liability insurance for the University of Illinois police officers. The Indiana campus police statute includes a clause that allows governing bodies of the respective institutions to expressly forbid police power to be granted, if they so choose. This statute also has a provision that allows campus police to remove persons from buildings or campus grounds whenever such persons refuse to leave after being requested to do so.

The campus police statute in Kansas specifically authorizes the University of Kansas Medical Center police facility to make emergency transports of medical supplies and transplant organs.

The Maryland statute which grants police authority also allows the Board of Regents to authorize presidents of the constituent institutions to make use of campus security forces or building guards instead of a campus police force if they so desire. A separate statute in Maryland allows the governor to appoint “special policemen” for private four-year institutions and community colleges if deemed necessary2.

According to the Massachusetts statute, “special state police officers” may be appointed at the request of the college or university by the Colonel of the State Police. These officers are appointed for three years and are subject to removal by the Colonel. They may also be reappointed after three years.

A rather unique feature found in the Michigan state statute directs the governing Board of Control to establish a public safety department oversight committee comprised of faculty, students and staff. This committee receives and addresses grievances by persons against public safety officers and it may also recommend to the institution disciplinary actions against the police officers.

regarding “use of force” and the equipment authorized for use by its officers in carrying out that policy.

The Virginia statute includes a unique feature that allows the governing boards of institutions of higher education to establish, equip and maintain auxiliary police forces. Members of the auxiliary police forces shall have the same authority as campus police officers when called on for assistance. These auxiliary officers must comply with the same requirements as the campus law enforcement officers as established by the Department of Criminal Justice Services.

Finally, the campus police statute in West Virginia provides that campus security officers also have the authority to assist local peace officers with traffic control on public highways in and around premises owned by the state of West Virginia. This is allowed whenever such traffic is generated as a result of an athletic event or other activity conducted or sponsored by state institutions of higher education and when such assistance has been requested by local peace officers.

Other Provisions for Granting Campus Police Authority

In South Carolina, police officers at public institutions derive their authority from a statute that primarily covers state constables3. For the states of Hawaii and Idaho, statutory reference is made only to the broad powers granted to their respective Board of Regents without mention of campus police. Likewise, no campus police statutes for the states of Nebraska, South Dakota or Arizona were found.

The Connecticut statute covers state colleges and universities only. Therefore, as a private institution, Yale University is not granted police powers under the statute. However, Yale police officers receive their police authority from another state statute, specifically Public Act 83-466 Section 3. This statute allows the city of New Haven, Connecticut, to appoint persons designated by Yale University to act as Yale University police officers4.

In Idaho there is no specific campus police statute, only a law that describes the broad administrative powers granted to the Board of Regents. Campus police departments at higher education institutions have no police authority; however, the University of Idaho and Boise State University contract for law enforcement services with their local police departments5.

institutions may appoint police officers under the “Company Police Act”. Under this statute, private educational institutions may apply to the Attorney General of the state and be certified as a company police agency. Individual applications for the company police officer must also be sent to the Attorney General.

DISCUSSION

The current study revealed wide variations in the statutes granting campus police authority throughout the United States. As with other laws, it appears that state legislatures often enact campus police statutes to solve or attempt to solve specific problems at a given time. For example, the increases in the number of automobiles on campus probably led to the inclusion of language such as that found in Mississippi’s statute that specifically requires the regulation of vehicular traffic and parking on campuses. Provisions that allow the removal of trespassers from campus facilities may have resulted from the Vietnam War era during which many campus police statutes were initially enacted. Legislatures have also been sensitive to the proper balance of police authority between campus law enforcement departments and their local counterparts. Gelber (1972) noted that historically many campuses required their officers to be deputized by local police authorities. A number of statutes also included language granting local police departments authority on campus.

In addition to granting full police authority to many campus police departments, statutes frequently reflected the regulatory role played by many campus police departments. Part of the history and tradition of campus law enforcement is reflected in statutory language that requires campus law enforcement officers to be university “rule enforcers” as well as “law enforcers”.

Campus police statutes vary greatly in length and specificity. Several of the statutes were very detailed while others were extremely concise and more limited in their scope. For example, Oklahoma and Virginia have rather lengthy comprehensive statutes covering several pages. In contrast, the campus police statute from the state of Minnesota is one paragraph in length.

states have passed such laws. The present study found the majority of states granting police authority to officers at public institutions. Furthermore, the powers of campus police at these institutions are generally equivalent to that of their local law enforcement counterparts. Frequently, campus police statutes also establish minimum selection and training standards for campus law enforcement officers similar to those required of local police.

The typical campus police statute today specifies that the ultimate appointing authority for campus police rests with the governing body or chief executive officer of the college or university. This is a situation parallel to the mayor or the city manager in a municipal setting, who also has the ultimate responsibility for supervising the police department. Many of the legislatures recognized that campus police may have need to exercise their police powers beyond the immediate geographic boundaries of the institution and included appropriate provisions. Given the mobility of today’s criminals, it is somewhat surprising that specific authority to engage in “hot pursuit” was not included in more campus police statutes. In contrast, more statutes included language specifying bonding or equipment requirements (15) than the number allowing campus police departments to enter into mutual aid agreements with local law enforcement agencies (9).

Today’s college campuses are often cities within cities and as such are vulnerable to serious crimes. The tens of thousands of students, faculty and visitors and the multi-million dollar investments in campus facilities and equipment require a professional level of police protection. Furthermore, litigation and recent federal and state legislation make it incumbent on campus executives to deal proactively with issues relating to campus crime and campus policing. Therefore, it would seem that consideration should be given to the enactment of comprehensive campus police statutes that provide the foundation for a professional response. This review of contemporary statutes provides an opportunity to examine the features that may be relevant in developing a model campus police statute. Based on the current review, it is suggested that a model statute include elements such as: appointing authority, jurisdiction, police officer qualifications and training requirements in compliance with standards required for other law enforcement officers.

violators who commit crimes on campus. States that do not provide police authority for officers working at private institutions or community colleges could consider doing so. For example, in Oklahoma, campus police departments at private institutions are considered “public” agencies for the limited purposes of law enforcement. Finally, a model statute should provide the governing board or chief executive officer of institutions of higher education with the option of establishing security departments that do not have sworn officers. However, if that option is chosen, the statute should mandate that local law enforcement officials be called to the campus to investigate all crimes once reported.

NOTES

The author would like to express appreciation to Dr Max Dertke for his review of this manuscript and very helpful comments. Also Ms Michelle Whitcomb was very helpful in locating statutes. Josh Martin of the National Association of College and University Attorneys was also of great help. Finally, various members of the International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators were of great assistance in this project.

This is a revision of a paper presented at the 1996 annual meeting of the American Society of Criminology. The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their insightful and helpful comments.

1. According to a follow-up phone interview with Lt Tim Banks of the University of Wyoming, campus police are appointed as “peace officers” of the state and as such have jurisdiction throughout the entire state.

2. This information regarding private institutions and community colleges was verified by Captain Richard Duran of the University of Maryland Police Department.

3. Chief Carl Stokes of the University of South Carolina provided the information regarding constable powers in his state.

4. This information was forwarded from Chief Allan R. Guyette, Chief of Police, Yale University.

REFERENCES

Atwell, R.M. (1988), Memorandum Regarding Campus Security, American Council on Education, Washington, DC.

Belkmap, J. and Erez, E. (1995), “The victimization of women on college campuses: courtship violence, date rape and sexual harassment”, in Fisher, B.S. and Sloan, J.S. (Eds), Campus Crime: Legal, Social and Policy Perspectives,

Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL.

Bordner, D.C. and Petersen, D.M. (1983), Campus Policing: The Nature of University Work,University Press of America, Lanham, MD.

Bromley, M.L. and Territo, L. (1990), College Crime Prevention and Personal Safety Awareness, Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL.

Castelli, J. (1990), “Campus Crime 101”, The New York Times Education Life,

4(November):1.

Gelber, S. (1972), The Role of Campus Security in the College Setting,United States Department of Justice, Washington, DC.

Griffaton, M. (1995), “State level initiatives and campus crime”, in Fisher, B.S. and Sloan, J.J. III (Eds), Campus Crime: Legal, Social and Policy Perspectives,

Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL.

Hollis, D.W. (1951), The University of South Carolina. Vol. I. South Carolina College, University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, SC.

Humphrey, D.C. (1976), From King’s College to Columbia 1746-1800,

Columbia University Press, New York, NY.

International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators (1995),

Campus Crime Report, 1991-1993, IACLEA, Hartford, CT.

Kaplin, W.A. (1990), The Law of Higher Education, 2nd ed., Jossey-Bassey Publishers, San Francisco, CA.

Kirkland, C. and Siegel, D. (1994), Campus Security. A First Look at Promising Practices, Office of Educational Research, US Department of Education, Washington, DC.

Lederman, D. (1994), “Crime on the campus”, The Chronicle of Higher Education,3(February):A33.

McGrane, R.C. (1963), The University of Cincinnati: A Success Story in Urban Higher Education,Harper & Row, New York, NY.

Mathews, A. (1993), “The campus crime war”, The New York Times Magazine,

7(March):38-47.

Nichols, W.D. (1986), The Administration of Public Safety in Higher Education,

Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL.

Ordovensky, P. (1990), “Students easy ‘prey’ on campus”, USA Today, 3(December):1A.

Peak, K. (1988), “Campus law enforcement. A national survey of administration and operation”, Campus Law Enforcement Journal, 19(5):33-5.

Peak, K. (1995), “The progressionalization of campus law enforcement: comparing campus and municipal law enforcement agencies”, in Fisher, B.S. and Sloan, J.J. III (Eds), Campus Crime: Legal, Social and Policy Perspectives,

Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, IL.

Siegel, D. and Raymond, C. (1992), “An ecological approach to violent crime on campus”, Journal of Security Administration, 15(2):19-29.

Sloan, J.J. (1992), “Campus crime and campus communities: an analysis of campus police and security”,Journal of Security Administration, 15(2):31-45.

Smith, M.C. (1988), Coping with Crime on Campus,Macmillan, New York, NY.

Wertenbaker, T.J. (1946), Princeton 1746-1896,Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

CASES

1. Donnellv. California Western School of Law, 246 Cal. Rptr. 199 (1988).

2. Duarte v. State, 151Cal. Rptr. 727 (1979).

3. Hartmanv. Bethany College, 778 F. Supp. 286 (1991).

4. Millerv. State of New York, 467N.E.2d493 (1984).

6. Petersonv. San Francisco Community College District, 685P.2d1193 (1984).

7. Whitlockv. University of Denver,744 p. 2d 54 (1987).

FEDERAL STATUTE

Student Right to Know and Campus Security Act (Public Law 101-542).

Appendix:

LIST OF OFFICIAL CODE COMPILATIONS TO WHICH CITATIONS REFER

Official Code of Georgia Annotated Hawaii Revised Statutes Annotated General Laws of Rhode Island Code of Laws of South Carolina 1976 South Dakota Codified Laws Tennessee Code Annotated Texas Codes Annotated Utah Code Annotated Vermont Statutes Annotated Code of Virginia 1950 Annotated Revised Code of Washington Annotated

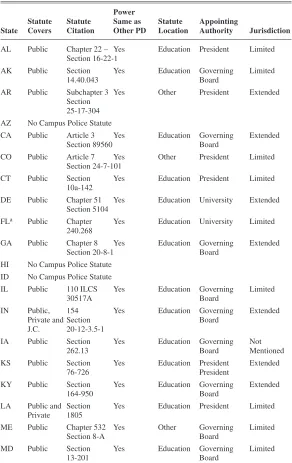

Table A1

FEATURES OFCAMPUSPOLICESTATUTES

Power

Statute Statute Same as Statute Appointing

State Covers Citation Other PD Location Authority Jurisdiction

AL Public Chapter 22 – Yes Education President Limited Section 16-22-1

AK Public Section Yes Education Governing Limited

14.40.043 Board

AR Public Subchapter 3 Yes Other President Extended Section

25-17-304 AZ No Campus Police Statute

CA Public Article 3 Yes Education Governing Extended

Section 89560 Board

CO Public Article 7 Yes Other President Limited Section 24-7-101

CT Public Section Yes Education President Limited 10a-142

DE Public Chapter 51 Yes Education University Extended Section 5104

FLa Public Chapter Yes Education University Limited 240.268

GA Public Chapter 8 Yes Education Governing Extended

Section 20-8-1 Board

HI No Campus Police Statute

ID No Campus Police Statute

IL Public 110 ILCS Yes Education Governing Limited

30517A Board

IN Public, 154 Yes Education Governing Extended

Private and Section Board

J.C. 20-12-3.5-1

IA Public Section Yes Education Governing Not

262.13 Board Mentioned

KS Public Section Yes Education President Extended

76-726 President

KY Public Section Yes Education Governing Extended

164-950 Board

LA Public and Section Yes Education President Limited Private 1805

ME Public Chapter 532 Yes Other Governing Limited

Section 8-A Board

MD Public Section Yes Education Governing Limited

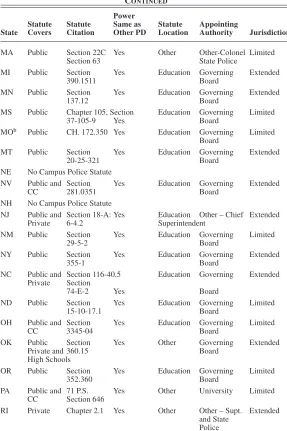

Table A1 CONTINUED

Power

Statute Statute Same as Statute Appointing

State Covers Citation Other PD Location Authority Jurisdiction

MA Public Section 22C Yes Other Other-Colonel Limited

Section 63 State Police

MI Public Section Yes Education Governing Extended

390.1511 Board

MN Public Section Yes Education Governing Extended

137.12 Board

MS Public Chapter 105, Section Education Governing Limited

37-105-9 Yes Board

MOb Public CH. 172.350 Yes Education Governing Limited Board

MT Public Section Yes Education Governing Extended

20-25-321 Board

NE No Campus Police Statute

NV Public and Section Yes Education Governing Extended

CC 281.0351 Board

NH No Campus Police Statute

NJ Public and Section 18-A: Yes Education Other – Chief Extended

Private 6-4.2 Superintendent

NM Public Section Yes Education Governing Limited

29-5-2 Board

NY Public Section Yes Education Governing Extended

355-1 Board

NC Public and Section 116-40.5 Education Governing Extended Private Section

74-E-2 Yes Board

ND Public Section Yes Education Governing Limited

15-10-17.1 Board

OH Public and Section Yes Education Governing Limited

CC 3345-04 Board

OK Public Section Yes Other Governing Extended

Private and 360.15 Board

High Schools

OR Public Section Yes Education Governing Limited

352.360 Board

PA Public and 71 P.S. Yes Other University Limited CC Section 646

RI Private Chapter 2.1 Yes Other Other – Supt. Extended and State

SC Private Chapter 116 Yes Education Governing Extended

4 year Section 59 Board

and 23-1-60

Table A1 CONTINUED

Power

Statute Statute Same as Statute Appointing

State Covers Citation Other PD Location Authority Jurisdiction

SD No Campus Police Statute

TN Public and Chapter Yes Education Governing Extended

CC 49-7-118 Board

TX Public and Section Yes Education Governing Extended

Private 51.203 2.123 Board

UT Public Section Yes Education Governing Limited

53B-3-104 Board

VT Public Chapter 75 Yes Education Governing Limited

Section 2283 Board

VA Public and Chapter 17 Yes Education Governing and Circuit

Private Section 22-232 Court Extended

WA Public Chapter Yes Education Governing Limited

28B.10.550 Board

WI Public Chapter Yes Education Governing Limited

36.11 Board

W.VA Public 18B-4-5 Yes Education Governing Extended WY Public Chapter 2 Yes Other University Extended

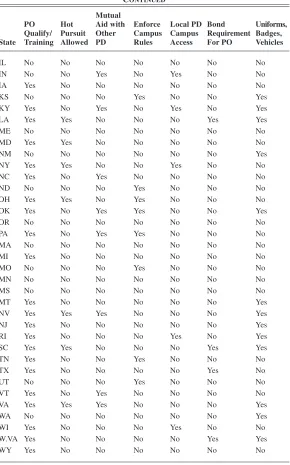

Table A2

ITEMS MENTIONED IN STATUTE

Mutual

PO Hot Aid with Enforce Local PD Bond Uniforms, Qualify/ Pursuit Other Campus Campus Requirement Badges, State Training Allowed PD Rules Access For PO Vehicles

AL No Yes No No No No No

AK Yes No No No No No No

AR No No No No Yes No No

CA Yes No No No No No Yes

CO Yes No No No Yes No No

CT No No Yes No No No No

DE No No No No Yes No No

FL Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes

Table A2 CONTINUED

Mutual

PO Hot Aid with Enforce Local PD Bond Uniforms, Qualify/ Pursuit Other Campus Campus Requirement Badges, State Training Allowed PD Rules Access For PO Vehicles

IL No No No No No No No

IN No No Yes No Yes No No

IA Yes No No No No No No

KS No No No Yes No No Yes

KY Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes

LA Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes

ME No No No No No No No

MD Yes Yes No No No No No

NM No No No No No No Yes

NY Yes Yes No No Yes No No

NC Yes No Yes No No No No

ND No No No Yes No No No

OH Yes Yes No Yes No No No

OK Yes No Yes Yes No No Yes

OR No No No No No No No

PA Yes No Yes Yes No No No

MA No No No No No No No

MI Yes No No No No No No

MO No No No Yes No No No

MN No No No No No No No

MS No No No No No No No

MT Yes No No No No No Yes

NV Yes Yes Yes No No No Yes

NJ Yes No No No No No Yes

RI Yes No No No Yes No Yes

SC Yes Yes No No No Yes Yes

TN Yes No No Yes No No No

TX Yes No No No No Yes No

UT No No No Yes No No No

VT Yes No Yes No No No No

VA Yes Yes Yes No No No Yes

WA No No No No No No Yes

WI Yes No No No Yes No No

W.VA Yes No No No No Yes Yes