Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:01

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Psychological Type and Academic Performance in

the Managerial Accounting Course

Charles J. Russo , Lasse Mertins & Manash Ray

To cite this article: Charles J. Russo , Lasse Mertins & Manash Ray (2013) Psychological Type and Academic Performance in the Managerial Accounting Course, Journal of Education for Business, 88:4, 210-215, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.672935

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2012.672935

Published online: 20 Apr 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 124

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2012.672935

Psychological Type and Academic Performance

in the Managerial Accounting Course

Charles J. Russo and Lasse Mertins

Towson University, Towson, Maryland, USA

Manash Ray

Kutztown University, Kutztown, Pennsylvania, USA

The authors examined the relationship between personality preferences as measured by the Keirsey Temperament Sorter (KTS-II) and academic performance for students in an undergrad-uate managerial accounting course. They developed a correlation model linking the strength of personality preferences in the KTS-II to academic performance by students who were enrolled in the managerial accounting course at a large public university in Maryland. There were 109 undergraduate business students who participated. The authors found that individuals with certain personality traits (nonguardian and intuitive types) performed better in manage-rial accounting tasks than guardian and sensing types. They anticipated these results because nonguardian and intuitive types have personality traits that are considered necessary for a successful career in management accounting.

Keywords: accounting course, Keirsey, management, performance, personality

There is a body of research concerning the relationship of student personality and academic performance in selected accounting courses including Bealing, Baker, and Russo (2006); Nourayi and Cherry (1993); Shackleton (1980); Wolk and Nikolai (1997); and Wheeler (2001). However, far less has been written about the relationship between student per-sonality type and the managerial accounting course. Al-though both financial accounting and managerial accounting are required courses in most all accounting programs, we be-lieve they represent different skill sets. This study extends the literature by investigating the relationships between person-ality preferences as measured by the Keirsey Temperament Sorter (KTS-II; Keirsey, 1998) and academic performance by students enrolled in the undergraduate managerial account-ing course.

We found that personality preferences have an impact on the performance in a managerial accounting course. Indi-viduals that did not belong to the guardian type category and intuitive individuals performed significantly better in the managerial accounting tasks than nonguardian types and

Correspondence should be addressed to Charles J. Russo, Towson Uni-versity, Department of Accounting, Stephens Hall 104C, 8000 York Road, Towson, MD 21252, USA. E-mail: crusso@towson.edu

sensitive students. In the remainder of the article, we re-view relevant literature, develop the hypotheses, discuss the methodology, present the results, and provide conclusions.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The theory that individuals exhibit specific personality types was introduced by Carl Gustav Jung in his book Psycho-logical Typesin 1921 (Storr, 1983). Jung described a set of dichotomous differences in the human psyche that he de-fined introverted and extroverted. In a related paper in 1936, Jung expanded his concepts by describing two additional dichotomous sets of psychological types thinking vs. feel-ing and sensation versus intuition (Storr, 1983). Myers and Briggs (Myers, 1998) expanded on Jung’s original theory of personality by creating a fourth dimension of judging and perceiving with judging types being organized and planned while perceiving types being flexible and adaptive.

Extroversion and introversion (E-I) involves how individ-uals prefer to focus their attention and gain their energy. Extroverts focus their attention and gain energy through in-teraction with the external world of people, activities, and things while introverts focus their attention and gain energy

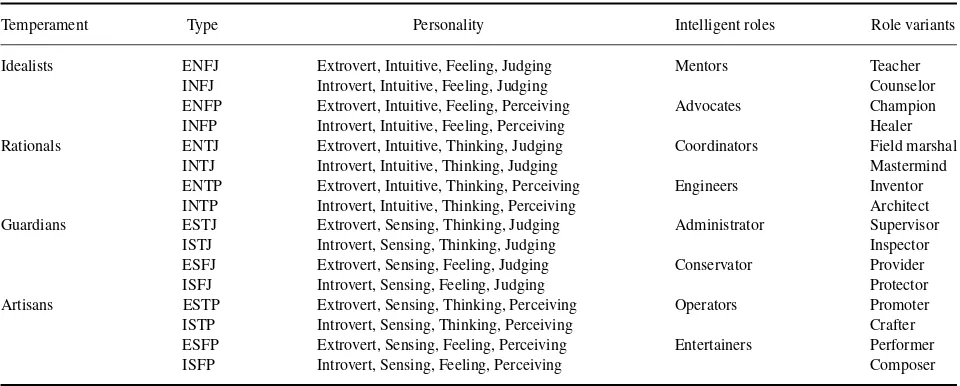

PSYCHOLOGICAL TYPE AND MANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING 211 TABLE 1

The 16 Personality Types

Temperament Type Personality Intelligent roles Role variants Idealists ENFJ Extrovert, Intuitive, Feeling, Judging Mentors Teacher

INFJ Introvert, Intuitive, Feeling, Judging Counselor ENFP Extrovert, Intuitive, Feeling, Perceiving Advocates Champion INFP Introvert, Intuitive, Feeling, Perceiving Healer Rationals ENTJ Extrovert, Intuitive, Thinking, Judging Coordinators Field marshal

INTJ Introvert, Intuitive, Thinking, Judging Mastermind ENTP Extrovert, Intuitive, Thinking, Perceiving Engineers Inventor INTP Introvert, Intuitive, Thinking, Perceiving Architect Guardians ESTJ Extrovert, Sensing, Thinking, Judging Administrator Supervisor

ISTJ Introvert, Sensing, Thinking, Judging Inspector ESFJ Extrovert, Sensing, Feeling, Judging Conservator Provider ISFJ Introvert, Sensing, Feeling, Judging Protector Artisans ESTP Extrovert, Sensing, Thinking, Perceiving Operators Promoter ISTP Introvert, Sensing, Thinking, Perceiving Crafter ESFP Extrovert, Sensing, Feeling, Perceiving Entertainers Performer ISFP Introvert, Sensing, Feeling, Perceiving Composer

through the inner world of ideas, impressions, and emotions (Myers & Briggs Foundation, 2011).

Schloemer and Schloemer (1997) discussed how sensing versus intuition involves how individuals gather and process information. Individuals with a preference for sensing rely more on their five senses, and are more focused on facts and details. Sensing types tend to organize input sequentially and prefer detailed instructions with concrete information. Intuitive types start with a view of broad concepts seeing patterns, connections, and trends organizing them as a more workable general framework. Intuitive types may dislike de-tail oriented activities, preferring to process information in a top down format as opposed to the detailed, fact-based, bottom-up approach of sensing types.

While the sensing (S) and intuitive (N) functions deal with how an individual gathers and processes information, the thinking (T) and feeling (F) functions deal with how an individual makes decisions. An individual’s decision-making processes are dominated by either thinking or feeling. Those individuals who conform to the thinking type definition tend to use a logical, objective decision process, while those who resemble the feeling type are inclined to use a value-based or subjective process which puts more emphasis on how the decision will impact others (Schloemer & Schloemer, 1997). Judging (J) types prefer to be planned, organized, while perceiving (P) types are less planned and may prefer to keep their options open. Perceiving types may be more sponta-neous and tend to rely more on their ability to adapt to a changing situation and are more spontaneous (Myers, 1998). Keirsey (1998) developed a 70-question survey that mea-sures the same 16 personality types as the Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) instrument. The 16 personality types listed in Table 1 are based on descriptions and discussion from Keirsey (1998). Based on the 16 personality types, Keirsey and Bates (1984) classified the four subtype combinations as the four temperaments of idealists (NFs), rationals (NTs),

guardians (SJs), and artisans (SPs). Keirsey then classified the four temperaments into intelligence roles and role vari-ants as described in Table 1.

Although most all of the 16 personality types can be found in all occupations, many occupations have a dominant type that appears more often than other personality types. With access to such information, advisors, faculty, and adminis-trators may be able to better determine why students select certain majors. Students can be better advised as to which occupations and work environments best match up with a student’s personality preferences.

We have chosen the KTS-II instrument because it was available in a 70-question print format that could be easily scored. The print version allowed us to have complete access to individual question responses enabling a more detailed analysis of results. The MBTI would have been sent offsite for scoring and would have provided the four-letter person-ality type, but not the individual responses to questions.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In 1980, Shackleton examined the MBTI preferences of 91 accountants and financial managers (Shackleton, 1980). The results revealed that the most common combination of pref-erences was 38.5% STJ type personality preference, and 58% introverted. In 1981, Jacoby examined the MBTI preferences of 333 accountants of Big 8 firms in the Washington, DC, area (Jacoby, 1981). Similar to Shackleton, Jacoby’s results showed the most common combination of preferences was 33.6% STJ. Of the STJ group, 13.8% was ESTJ and 19.8% was ISTJ. Kreiser, McKeon, and Post (1990) conducted a similar study of CPAs in public practice. The results of this study indicated that the ISTJ and ESTJ were the most com-mon personality types.

Utilizing the MBTI instrument, Nourayi and Cherry (1993) examined the relationship between the performance of several students in seven different accounting courses and their individual personality preferences. The only significant relationship found was that students categorized as S outper-formed N students in three (tax, auditing and intermediate II) of the seven courses analyzed in their study.

Wolk and Nikolai (1997) administered the MBTI to 94 accounting graduate students and to 98 accounting faculty members. They also examined 152 undergraduate account-ing students usaccount-ing data from the 1993 study done by Fisher and colleagues (1993). Chi-square tests indicated that the undergraduate students were more likely to prefer the S) component over the intuition (I) component than were the graduate students. Undergraduate students were more likely to prefer the feeling (F) component over the thinking (T) component than were graduate students.

Schloemer and Schloemer (1997) examined the person-ality preferences of CPA firm professionals. The results in-dicated that the STJ combination is the most common com-bination of preferences for the total subjects in the sample across audit, tax, and management consulting. When exam-ining rank, partners were most often ENTJs while managers, seniors, and staff members were most often ESTJs. The in-tuitive (N) type of partners was 61% to 39%.

Wheeler (2001) published a review of the literature of the application of the MBTI in accounting research and found 16 published accounting research articles using the MBTI instrument. Of the 16 articles, four examined the relation-ship between academic performance of accounting students and their indicated MBTI personality type. Specifically, Ott, Mann, and Moores (1990) found that individuals categorized as sensing (S) and thinking (T) performed better, as measured by course grades, in courses using the lecture method.

Bealing et al. (2006) examined whether incoming ac-counting majors have a predisposition to a certain type and whether the personality types of accounting majors differ from other business majors. The authors administered the KTS-II instrument to 56 freshmen accounting majors en-rolled in the initial Principles of Accounting course, 54 business majors enrolled in the basic financial accounting course for nonaccounting majors, and 27 sophomore ac-counting majors enrolled in Intermediate Acac-counting I. Re-sults for the accounting majors revealed 67.28% of the ac-counting majors were SJ personality types. The results for nonaccounting majors revealed that 22.4% of the nonac-counting majors possessed the ESTJ personality type and the ESTJ type was the dominant personality profile for all business majors, at 24.8%.

Bealing, Russo, Staley, and Baker (2007) examined six specific questions of the KTS-II that related to the sensing (S) and intuitive (N) dimensions of Jungian personality type and whether there is a correlation between the strength of students’ specific personality preferences and the letter grade they received in their introductory accounting course. The authors used a chi-square test and the root mean square error

of approximation (RMSEA) to assess the overall fit of the model to the data. The results revealed that students with the sensing (S) dimension performed better than students with the intuitive (N) dimension.

HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

In this study, we examined whether students with certain per-sonality characteristics do better than others in a managerial accounting course. The characteristics between managerial and financial accounting differ in several ways: manage-rial accounting emphasizes reports that are future-oriented whereas financial accounting provides reports in the form of financial statements that are based on historical informa-tion. The end product of financial accounting are financial statements which focus on providing information to exter-nal stakeholders while managerial accounting covers topics including job-order costing, process costing, cost-volume-profit analysis, capital budgeting, relevant costing and other topics that focus more on problem solving and analytical skills (Garrison, Noreen, & Brewer, 2006; Jackson, Sawyers, & Jenkins, 2007).

Based on these differences between managerial and finan-cial accounting, managerial accountants need a different skill set than financial accountants. In our opinion, it seems that individuals who have a more analytical approach to problem solving would perform better in managerial accounting tasks than individuals that prefer a less flexible predefined step-by-step approach in problem-solving tasks. On the other hand, individuals who are detail oriented and good at following rules are expected to perform well in a financial account-ing environment. Thus, the relationships between personal-ity preferences and student performance should reflect these differing constructs in managerial accounting courses.

Guardians (SJ types) are practical, disciplined, process data sequentially, follow rules, and prefer to solve prob-lems using existing methods or predetermined procedures as opposed to developing new approaches (Keirsey, 1998, 2010). In a prior study Bealing et al. (2007) examined per-formance in the financial accounting course, and their results revealed that SJ types outperformed other types. However, we believe SJ types may not necessarily be the top perform-ers in the managerial accounting course. We anticipate that nonguardians (NF-Idealists, NT-Rationals, and SP-Artisans) may perform better in a managerial accounting than SJ-Guardians. Therefore, our first hypothesis was the following:

Hypothesis 1(H1): Nonguardian types would perform better

in a managerial accounting course thanguardian types.

In addition, we examined whether students with the intuitive (N) dimension outperformed students with the sensing (S) dimension in a managerial accounting class. Sensing individuals usually process information sequentially or step by step. They are also practical, sensible, and factual

PSYCHOLOGICAL TYPE AND MANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING 213

(Bloom & Snow, 1994). In contrast, intuitive types, who are generally not as detail oriented, process information globally by first seeing patterns and trends and then work toward more specific concepts (Bealing, Staley, & Baker, 2008; Keirsey & Bates, 1984). They are also imaginative, speculative, and future oriented (Bloom & Snow, 1994). The traits of intu-itive types suggest that N types may perform better in en-vironments where flexible, future oriented, and imaginative thinking are needed. Thus, these characteristics may be a bet-ter fit for the managerial accounting skill set. Although prior studies have shown that S-types have outperformed N-types in financial accounting, we anticipated that N-types would outperform S-types in managerial accounting.

H2: Intuitive (N) types would perform better in a managerial

accounting course than sensing (S) types.

METHODOLOGY

Data Collection

We administered the KTS-II instrument plus the 10 academic and demographic questions to 109 business majors enrolled in five sections of the undergraduate managerial account-ing course taught by three different professors. The survey took place during a regular scheduled class and the survey was completed in approximately 20 min. All five sections used the same text materials, covered the same chapters, and had four exams including a comprehensive final exam. The participants were 36% women and 64% men.

Variables

The dependent variable was an adjusted score of the fi-nal exam grade in the managerial accounting class. The final exam grades were adjusted so that the average final exam scores were identical among the managerial account-ing courses. We chose the final exam grade over the course grade to eliminate any subjective influences that may have affected the final grades (e.g., differences in grading home-work assignments among instructors). In addition, the types of questions that the students needed to answer in the final exams (mainly logical and analytical questions) are good rep-resentations of the skill sets for the managerial accounting.

We also looked at the dependent variables of manage-rial accounting course grade and financial accounting course

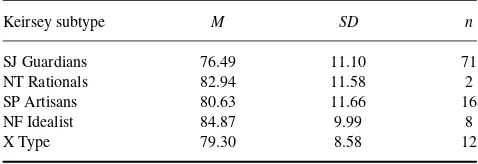

TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics (Adjusted Final Exam Score)

Keirsey subtype M SD n

SJ Guardians 76.49 11.10 71 NT Rationals 82.94 11.58 2 SP Artisans 80.63 11.66 16

NF Idealist 84.87 9.99 8

X Type 79.30 8.58 12

TABLE 3

Analysis of Variance Results (Guardians Versus Nonguardians)

df Sum of squares Mean square F p Between groups 1 553.95 553.95 4.75 .031 Within groups 107 12471.45 116.560

Total 108 13025.40

grade to compare student performance differences by person-ality type across both the managerial accounting and financial accounting courses.

The independent variables included temperament of the participant, EI score, SN score, TF score, and JP score. Tem-perament of the participant is a categorical variable. Keirsey and Bates (1984) described the four temperaments as (a) ide-alists (NF types), (b) rationals (NT types), (c) guardians (SJ types), and (d) artisans (SP types). The independent vari-ables for the four dichotomous pairs extroverted (E) versus introverted (I) score, sensing (S) versus intuitive (N) score, thinking (T) versus feeling (F) score, and judging (J) versus perceiving (P) score are interval–ratio variables.1

Data Analysis

We compared the final exam scores among the Keirsey char-acteristics using analyses of variance (ANOVAs). We tested the differences in students’ performance for one-letter char-acteristics (e.g., N vs. S), for two-letter charchar-acteristics (e.g., SJ vs. NT), and for four-letter characteristics (e.g., ESFJ vs. ESTJ). We also tested whether certain demographic vari-ables may impact a student’s performance in the managerial accounting class (e.g., gender, age, native language).

RESULTS

Hypothesis 1

H1hypothesized that nonguardians types would perform

bet-ter in the managerial accounting course than guardian types. We employed an ANOVA to test the statistical difference be-tween the two letter character types. The descriptive statistics (Table 2) show that the guardians made up 65% of the sample (71 of 109 individuals). The means of the adjusted final exam

TABLE 4

Guardians Versus Nonguardians Group Means (Adjusted Final Exam Score)

Group M SD n

Guardian 76.49 11.10 71

Nonguardian 81.22 10.20 38

Total 78.14 10.98 109

TABLE 5

Analysis of Variance Results (Sensing Versus Intuitive)

df Sum of Squares Mean Square F p Between groups 1 490.42 490.42 4.04 0.047 Within groups 101 12270.59 121.49

Total 102 12761.00

scores reveal that the subgroup guardians (76.49) performed well below the other subgroups. We were not able to com-pare the subtype groups individually because the rationals and idealists groups (2 and 8 members) were too small to make informative comparisons.

However, we compared the performance of the guardians group with the performance of all other groups combined, the nonguardians (Tables 3 and 4). The results show that the guardian (SJ) types (76.49) performed significantly (p

< .05) worse than nonguardians (81.22). Therefore,H1 is

supported.

Hypothesis 2

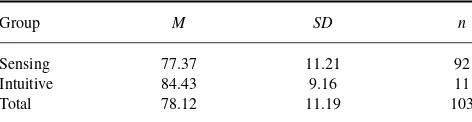

H2hypothesized that intuitive (N) types would perform

bet-ter in a managerial accounting course than would sensing (S) types. We employed another ANOVA to test the second hypothesis. We anticipated that intuitive (N) types would outperform sensing (S) types in the managerial accounting course. The results in Tables 5 and 6 confirm the anticipated outcomes. Intuitive (N) types scored an average of 84.43 on the final exam while sensing (S) types only scored an average of 77.37.

This difference is statistically significant (p<.05).

There-fore,H2is also supported. This analysis did not include any

X-types, which reduced the sample size from 109 to 103 subjects.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The results of this study differ from prior studies that have examined academic performance and personality type in accounting courses. The results indicate that nonguardian types outperform their guardian counterparts and intuitive

TABLE 6

Sensing Versus Intuitive Group Means (Adjusted Final Exam Score)

Group M SD n

Sensing 77.37 11.21 92

Intuitive 84.43 9.16 11

Total 78.12 11.19 103

(N) types outperform sensing (S) types in the managerial accounting course. The results also provide a validation of the innate differences and required skill sets for financial and managerial accounting. The results have implications for accounting educators. Accounting educators now have to accommodate the role of different personality types for financial and managerial accounting courses.

This study established that guardians and sensing types performed poorly when compared to nonguardians and intu-itive types. Instructors may do well to emphasize the different skill sets required for managerial accounting and use addi-tional exercises with analysis and interpretation so that the guardians and sensing types actively engage in mastering the different set of skills needed to succeed in the course. Ad-ditional use of collaborative group projects where different personality types learn and work together may also mitigate some of the personality effects and create more opportunities for the guardians and sensing types.

There are three major implications for future researchers. First, the number of N types is a limitation of this study. The study can be replicated to expand the size of the sample to provide a higher number of N types in the sample. An expanded sample will also ensure that the academic perfor-mance of all four Keirsey subtypes, SJ, NT, SP, and NF, can be compared. Second, the different skill sets required for fi-nancial and managerial accounting can be explored further by examining the personality types of certified accounting professionals such as CPAs and CMAs as well as account-ing firm partners versus controllers and internal auditors. In addition, future studies can look at differences in results for different instructional models such as online courses versus lecture courses. Finally, future researchers should examine if added weight on group projects and collaborative learning can mitigate the effect of personality types.

NOTE

1. The data were coded on a scale of+10 to –10 for E versus I, and on a +20 to –20 scale for S versus N, T versus F, and J versus P, so that the strength of the preference of the dichotomous pairs could be treated as a numeric variable.

REFERENCES

Bealing, W. J., Baker, R. L., & Russo, C. J. (2006). Personality: What it takes to be an accountant.Accounting Educator’s Journal,16, 119–128. Bealing, W. J., Russo, C. J., Staley, A. B., & Baker, R. L. (2007, March). A short form of the Keirsey Temperament Sorter to predict success in an introductory accounting course. Paper presented at the NEDSI (Northeast Decision Sciences Institute) 2007 Annual Meeting, San Juan, Puerto Rico. Bealing, W. J., Staley, A. B., & Baker, R. L. (2008, March).Personality and accounting: Does a financial aptitude exist?Paper presented at the NEDSI 2008 Annual Conference, Brooklyn, NY.

PSYCHOLOGICAL TYPE AND MANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING 215 Bloom, A. J., & Snow, R. M. (1994). Ethical decision making styles in

the workplace: Relations to the Keirsey Temperament Sorter.Systems Research,11, 59–63.

Fisher, D., Ott, R., Donnelly, D., & Stewart, K. (1993, April).A study of the relationship between accountants’ moral reasoning and personality type. Paper presented at 1993 Western Region Annual Meeting of the American Accounting Association, San Diego, CA.

Garrison, R., Noreen, E., & Brewer, P. (2009).Managerial accounting(11th ed.). New York, NY: Irwin/McGraw Hill.

Jackson, S., Sawyers, R., & Jenkins, G. (2007).Managerial accounting: A focus on ethical decision making(4th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Jacoby, P. F. (1981). Psychological types and career success in the account-ing profession.Research in Psychological Type,4, 24–37.

Keirsey, D. (1998).Please Understand Me II: Temperament, character, intelligence. Del Mar, CA: Prometheus Nemesis.

Keirsey, D. (2010).Overview of the four temperaments, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.keirsey.com/4temps/overview temperaments.asp#; Keirsey, D., & Bates, M. (1984).Please Understand Me: Temperament,

character, intelligence, Del Mar, CA: Prometheus Nemesis.

Kreiser, L., McKeon, J. M. Jr., & Post, A. (1990). A personality profile of CPAs in public practice.Ohio CPA Journal,49, 29–34.

Myers, I. (1998).Introduction to type(6th ed.). Menlo Park, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Myers & Briggs Foundation. (2011).Extroversion or introversion, 2011. Retrieved from http://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/ mbti-basics/extraversion-or-introversion.asp

Nourayi, M., & Cherry, A. (1993). Accounting students’ performance and personality types. Journal of Education for Business, 69, 111– 115.

Ott, R. L., Mann, M. H., & Moores, C. T. (1990). An empiri-cal investigation into the interactive effects of students’ personality traits and method of instruction (lecture or CAI) on student perfor-mance in elementary accounting.Journal of Accounting Education,8, 17–35.

Schloemer, P. G., & Schloemer, M. S. (1997). The personality types and preferences of CPA firm professionals: An analysis of changes in the profession.Accounting Horizons,11, 24–39.

Shackleton, V. (1980, November). The accountant stereotype: Myth or real-ity?Accountancy, 122–123.

Storr, A. (1983).The essential Jung. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wheeler, P. (2001). The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and applications to accounting education and research.Issues in Accounting Education,16, 125–150.

Wolk, C., & Nikolai, L. A. (1997). Personality types of accounting stu-dents and faculty: Comparisons and implications,Journal of Accounting Education,15, 1–17.