Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:54

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Critical Thinking in the Business Classroom

Joanne R. Reid & Phyllis R. Anderson

To cite this article: Joanne R. Reid & Phyllis R. Anderson (2012) Critical Thinking in the Business Classroom, Journal of Education for Business, 87:1, 52-59, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.557103

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.557103

Published online: 21 Nov 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 549

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.557103

Critical Thinking in the Business Classroom

Joanne R. Reid

Corporate Development Associates, Inc., Lombard, Illinois, USA

Phyllis R. Anderson

Governors State University, University Park, Illinois, USA

A minicourse in critical thinking was implemented to improve student outcomes in two sessions of a senior-level business course at a Midwestern university. Statistical analyses of two quanti-tative assessments revealed significant improvements in critical thinking skills. Improvements in student outcomes in case studies and computerized business simulations were observed.

Keywords: business administration, California Critical Thinking Skill Test, critical thinking, metacognition, transfer

In a series of proposals, the Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills [SCANS] defined the skills needed by industry and the educational requirements needed for workers to achieve those skills (Brock, 1991; Kane, Berryman, Goslin, & Meltzer, 1990; Whetzel, 1992). Six thinking skills were identified:

A. Creative Thinking—generates new ideas

B. Decision Making—specifies goals and constraints, gener-ates alternatives, considers risks, and evalugener-ates and chooses best alternative

C. Problem Solving—recognizes problems and devises and implements plan of action

D. Seeing Things in the Mind’s Eye—organizes, and pro-cesses symbols, pictures, graphs, objects, and other informa-tion

E. Knowing How to Learn—uses efficient learning tech-niques to acquire and apply new knowledge and skills

F. Reasoning—discovers a rule or principle underlying the relationship between two or more objects and applies it when solving a problem. (Kane et al., p. xi)

These thinking skills had been previously defined by psy-chologists and educators as critical thinking. For example, six years prior to the SCANS report, the noted psychologist and

Correspondence should be addressed to Joanne R. Reid, Corporate De-velopment Associates, Inc., P. O. Box 1206, 2201 S. Highland Avenue, Lombard, IL 60148, USA. E-mail: jrreid5530@sbcglobal.net

educator Diane Halpern publishedThought and Knowledge:

An Introduction to Critical Thinking(1984). A definitive text on the subject of critical thinking, Halpern assembled the 10 basic skills and capacities necessary to think critically.

She definedcritical thinkingas “the use of those cognitive

skills or strategies that increase the probability of a desirable outcome” (Halpern, 1998, p. 450). Reid (2009a) defined crit-ical thinking as “the conjunction of knowledge, skills and strategies that promotes improved problem solving, ratio-nal decision making and enhanced creativity” (p. 2). Critical thinking is recognized as an essential part of education and a valuable life skill (Case, 2005; Giancarlo, Blohm, & Urdan, 2004).

However, there is little evidence that critical thinking is being taught or that critical thinking skills are being learned. Federal studies have equated Americans’ poor reading skills, mathematics skills, and understanding of scientific princi-ples with inadequate critical thinking skills (Flawn, 2008; Grigg, Donahue, & Dion, 2007; National Science Board, 2004; Shettle et al., 2007). Winn (2004) emphasized these failures, enumerating the high costs of the ineffective teach-ing of critical thinkteach-ing. Case (2005, p. 45) stated that he was disheartened by the failures to teach critical thinking.

PURPOSES OF THE STUDY

There were two purposes for this study. The primary pur-pose was to improve students’ outcomes in their final, cap-stone course prior to graduation. The second was to as-sess the effectiveness of a newly developed critical thinking

CRITICAL THINKING IN THE BUSINESS CLASSROOM 53

pedagogical treatment. However, because this treatment was new and untested, it would be difficult within a limited study such as this one to assess its effects on the business course of study quantitatively. Therefore, it was necessary to assess the critical thinking treatment before attempting to perform sim-ilar quantitative studies of its effectiveness on the business course of study.

The research reported in this study considers the second of these purposes, namely three interrelated questions con-cerning the quantitative analysis of the acquisition and use of critical thinking skills: a) Can critical thinking can be taught? b) Can critical thinking be learned? And c) Can critical think-ing be transferred across domains?

BRIEF LITERATURE SURVEY OF TEACHING AND LEARNING CRITICAL THINKING

Questions regarding the teaching, learning, and transfer of critical thinking skills have been debated for many years and by many authors. Many authors are convinced that critical thinking cannot be taught. Case (2005) cited the necessity of domain knowledge. Rosaen (1988) suggested the rele-gation of the teaching of critical thinking skills to higher order skills. The lack of teacher’s critical thinking skills was suggested by Willingham (2007). McKee (1988) discussed teachers’ refusal to incorporate critical thinking into their classroom instruction. Bloom and Weisberg (2007) consid-ered conflicts between sophisticated explanations provided by critical thinking as opposed to intuitive explanations de-veloped in childhood. In a personal communication, Dr. Ken Silber (personal communication, August 2008) of Northern Illinois University declared that nobody who had tried to demonstrate that critical thinking could be taught and learned had succeeded. In his words, they “hadn’t moved the needle.” However, other authors have suggested that, if the proper methods are employed, then critical thinking skills could be learned. P. Facione, Facione, and Giancarlo (2000) reasoned that, “given the empirical results, an effective approach to teaching for and about thinking must include strategies for building intellectual character” (p. 1). P. Facione (2007) dis-cussed the needs for training in critical thinking skills and also for developing the disposition for critical thinking. Halpern (1989, 1993, 1997, 1998, 1999; Halpern & Nummedal, 1995; Halpern & Riggio, 2003) wrote extensively regarding the teaching of critical thinking and its acquisition by students. Leppard (1993) opined that 30 years of research and schol-arship supported the view that critical and creative thinking can be taught if appropriate instructional strategies are used. Vermunt (1996) asserted,

The results indicate that in order to bring about construc-tive and independent learning behavior, instruction should be mainly aimed at developing self-regulated control

strate-gies and mental learning models in students in which the construction and use of knowledge are central. (p. 48)

Few researchers have reported validated results of ef-forts to teach critical thinking skills. This lack of valida-tion was one of the underlying causes of skepticism regard-ing the teachregard-ing or learnregard-ing of critical thinkregard-ing skills. One of the few to present such a validated study were West-brook and Rogers (1991), who reported significant gains in logic and reasoning using descriptive learning techniques, as measured by Lawson’s Seven Logic Tasks and Lawson’s Classroom Test of Scientific Reasoning. Combs (1992) re-ported that cooperative learning increased students’ scores in the Iowa Tests of Basic Learning. Tiwari, Lai, and Yuen (2006) used the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory to demonstrate that students involved in problem-based learning achieved higher scores in overall improve-ment, truth seeking, analyticity, and critical thinking confi-dence. In pharmacology, Abbate (2008) used the ATI Critical Thinking Assessment to find weak trends toward improved explanation, inference, evaluation, and self-regulation along with a weak positive relationship to overall critical thinking. However, none of these researchers demonstrated improved critical thinking skills deriving from instruction in critical thinking.

THE CRITICAL THINKING TREATMENT

The research problem was to determine whether critical thinking could be taught, learned, or transferred between domains. This would require the development and imple-mentation of a course of study in critical thinking because no such course was extant. Therefore, a sound theoretical foun-dation in critical thinking was the first requirement in the development of such a course of study. Second, an instruc-tional design model was needed to provide the pedagogical content and structure needed to develop and implement such a course of study. Third, a validated and reliable assessment was needed to measure any acquisition of critical thinking skills that might occur. Fourth, a sufficiently large number of test subjects had to be located and who would agree to par-ticipate in the course and research study. Finally, the results of this experimental course of study would have to be distin-guished from the results expected from the extant course of study.

First Requirement: Theoretical Foundation

The first need was satisfied by the extensive literature gener-ated by Dr. Diane Halpern, Director of the Berger Institute for Work, Family, and Children at Claremont McKenna College, Past President of the American Psychological Society, and recognized expert in the field of critical thinking. In 1989,

she publishedThought and Knowledge: An Introduction to

Motivation

Attention Relevance Confidence Satisfaction

Instruction in CT Skills

Self-awareness Logical processes Methods of proof Pseudo proofs

Problem solving / decision making

Metacognitive Training

Knowledge and training to develop recognition of the need and activation of critical thinking processes

Structure Training

In-depth practice to recognize and use critical thinking skills in multiple contexts.

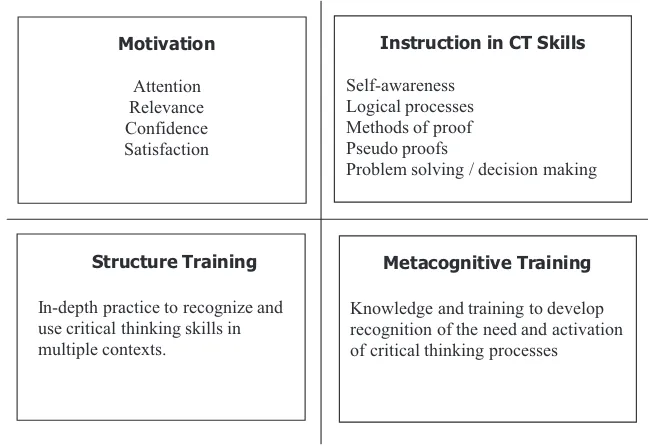

FIGURE 1 Concept map of teaching for critical thinking (Halpern, 1998).

Critical Thinking, describing in exquisite detail the techni-cal parameters of crititechni-cal thinking. However, this tome was not only large and intimidating, but ill suited for use as a

textbook. Subsequently, Halpern published Critical

Think-ing Across the Curriculum: A Brief Edition of Thought and Knowledge (1997). Her reasons for writing this condensed version were to have it serve as a,

companion text that can be used in virtually any course where critical thinking is valued. It can also stand alone for use by anyone who wants to know what cognitive psychologists and educators have found that “works” to improve learning, remembering, thinking and knowing. (1997, p. vii)

However, even a condensed version of Thought and

Knowledge proved to be both dense and challenging. Fur-ther, she had provided no philosophical foundation or content structure for its use in a classroom. As such, even a college-level teacher may be challenged to master the intricacies of logic and pedagogy required to convert the text into a course of study.

In 1998, Halpern provided the theoretical content and structure of such a course of study, which she called “Teach-ing for Critical Think“Teach-ing” (TCT). Halpern defined the goal of TCT as “to promote the learning of transcontextual thinking skills and the awareness of and ability to direct one’s own thinking and learning” (1998, p. 451). Within this context, she proposed a “model for teaching critical thinking skills so they will transfer across domains of knowledge,” consist-ing of four constituent elements (as shown in Figure 1), the Concept Map of Teaching for Critical Thinking. The first component of the TCT pedagogical strategy was the dispo-sitional or attitudinal element. The second was instruction in

and practice of critical thinking skills. The third component was structure training to facilitate transfer across contexts or domains. Finally, a metacognitive component was used to direct and assess thinking.

Second Requirement: Instructional Design

Although Halpern presented a construct and structure, it was essential to translate that into instructional content. Foshay, Silber, and Stelnicki (2003) provided the needed instruc-tional design methodology. Borrowing heavily from Merrill (2002, 2007); Clark, Yates, Early, and Moulton (2006); and

Kirshner, Sweller, and Clark (2006), Foshay et al. wrote

Writ-ing TrainWrit-ing Materials That Work: How to Train Anyone to Do Anything. In this book, they describe a 5-step model of instructional design that provides a parallel construction to Halpern’s model. This model is shown in Figure 2. The Cog-nitive Training Model (CTM; Foshay et al.)

Third Requirement: Assessment Instruments

The first assessment instrument was the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST), as recommended by Halpern (1993). This test derives from a pioneering effort by P. Fa-cione (1990) in which he convened a Delphi panel of 46 scholars and educators to develop the principles on which critical thinking assessment instruments were developed and implemented. One of these instruments, the CCTST, has un-dergone vigorous and extensive testing, evaluation, and vali-dation (N. C. Facione, 1997; N. C. Facione & Facione, 1997; N. C. Facione, Facione, Blohm, & Gittens, 2008; Phillips, Chestnut, & Rospond, 2004). This assessment instrument uses five scales to measure critical thinking skills: induc-tive reasoning, deducinduc-tive reasoning, analysis, inference, and

CRITICAL THINKING IN THE BUSINESS CLASSROOM 55

Learners Must Do This to Learn Trainers Put These Elements in Lessons to Help Learners

1. Select the information to attend to.

Heighten attention and focus it on new knowledge being taught because that new knowledge is seen as important and capable of

being learned

Attention: Gain & focus learner’s attention on the new knowledge.

WIIFM: What’s in it for me?

YCDI: You can do it.

2. Link the new information to the existing knowledge.

Put the new knowledge into an existing framework by recalling existing / old knowledge related to the new knowledge and

linking it to the old.

Recall existing knowledge.

Relate the new knowledge and the old knowledge.

3. Organize the information.

Organize new knowledge in such a way that matches the organization already in mind for related existing knowledge to make it easier to

learn, cut mental processing time, minimize confusion, and stress only relevant

information.

Structure of content

Objectives

Chunking

Text layout

Illustrations

4. Assimilate the new knowledge into existing knowledge.

Integrate the knew knowledge into the old knowledge so they combine to produce a new

unified, expanded and reorganized set of knowledge

Present new knowledge.

Present examples.

5. Strengthen the new knowledge in memory.

Strengthen the new knowledge so that it will be remembered and can be brought to bear in

future job and learning situations.

Practice Feedback Summary Test On-the-job application

FIGURE 2 The Cognitive Training Model.

evaluation. Individual and group results are reported as nu-meric values and as histograms.

In the present study, the CCTST was used in two different ways. First, the CCTST was used as a pretest and posttest in both of the experimental classes to determine if critical thinking skills had been acquired. Second, the CCTST was used to determine the difference between the acquisitions of critical thinking skills in the experimental classes relative to the CT skills acquired in the control class.

The second assessment instruments were 10-question, true–false, chapter quizzes provided by Halpern and Rig-gio (2003). These quizzes fulfilled the requirements of a quasiexperimental, pretest–posttest protocol. The tests, de-signed to test the student’s knowledge, were comprehen-sive for each chapter. They were published in Halpern and Riggio’s text, which was intended to be used in

conjunc-tion withCritical Thinking Across the Curriculum(Halpern,

1997), the main critical thinking text for the pedagogical treatment. The Halpern and Riggio module–chapter quizzes were shown to be reliable and to be valid in terms of their

construct validity, content validity, and user validity (Reid, 2009b).

Fourth Requirement: Experimental Venue

The venue for the course of instruction was a senior class in business administration at a Midwestern university. How-ever, the instructor (Dr. Anderson) required that the course be integrated into the established course of study and reflect business problems and solutions. Dr. Reid and Dr. Ander-son worked together to add critical thinking content to the business course case studies, which were within the business class textbook.

METHOD

The sample was of three sections of a senior-level, capstone course in business administration, two of which were exper-imental and one was the control. Thirty-nine students were

enrolled in the first and the second experimental classes. Sixteen individuals took part in one or more of the research phases in the first class. Twenty-three took part in one or more phases of the research in the second class. The final sample

(n =34) contained only those students who completed the

pretest and the posttest of the CCTST. Twenty-one students participated in the control class.

Dr. Reid developed a pedagogical treatment based on

Halpern’s (1997)Critical Thinking Across the Curriculum,

congruent with the principles of the Thinking for critical thinking model while using the CTM as the instructional design paradigm. The prepared materials were contained in a loose-leaf notebook so that new materials could easily be added or old materials readily modified and replaced.

This unit of instruction consisted of 11 modules of approx-imately 1–1.5 hr of class time. This corresponded to one in-troductory module, nine book chapters of the Halpern (1997) text, and one wrap-up session. Each module, corresponding to a chapter in the Halpern text, contained a true–false quiz; a computer-aided, multimedia assisted lecture; a discussion of the previous chapter assignment; a new chapter assignment; and a business case study.

It was necessary to determine if the critical thinking com-ponent was transferred to the business course. This was ac-complished by incorporating critical thinking skills into the weekly case study analyses. Business case studies were a reg-ular part of the capstone course in business administration. We examined case studies from the regular text for business content, which emphasized critical thinking skills. A grad-ing rubric was prepared to assess the combination of business and critical thinking skills employed by the students’ in their analysis.

The students were also assigned a major case study of a corporation. The students were required to use the full gamut of all the knowledge they had gained in their business courses to analyze the corporation. In addition, they were required to use their critical thinking skills to assess their case study corporation’s tactics and strategies to determine whether they would have been different had critical thinking skills been utilized.

RESULTS

Sample–Control Analyses

Because it was important to separate the effects of the criti-cal thinking treatment from the effects of the regular business course, it was necessary to compare the results of the CCTST from the experimental classes with that of the control class. Because of logistical problems, only one CCTST was ob-tained from the control capstone class. Because this test was taken at the end of the capstone course of study, it corre-sponded in time and business course content to the posttests taken by the test subjects. The comparison the of control, the

TABLE 1

Control Versus Experimental Classes

Control (n=21) Experimental (n=34)

CCTST Pretest Posttest Pretest Posttest

Percentile — 36.2 36.3 50.7

experimental pretest, and the experimental posttest results of the CCTST are shown in Table 1.

The values of the seven parameters of the CCTST were identical for the control class and the experimental pretest classes, within the reporting error of the assessment instru-ment. The results of the control class were within one-tenth of a unit to the corresponding experimental pretest class for all seven variables. Therefore, for the purposes of this study, only the pretest and posttest experimental values were used to derive the statistical significance of the experiment results.

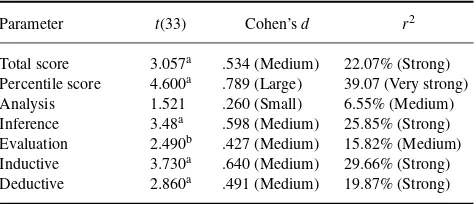

Experimental Classes’ CCTSTt Tests

Because it was important to determine effects of the criti-cal thinking pedagogicriti-cal treatment, the scores of the pretest CCTST from the experimental classes were compared with their corresponding posttests. The students’ scores in the pretest and posttest CCTST were compared using a repeated

measuresttest. In each six of the seven parameters of the

CCTST, thetscores were found to be significant. The

analy-sis parameter was shown to be statistically insignificant. The evaluation parameter was found to be significant at the 99% confidence level. The other five parameters were significant at greater than the 99.5% level. Based on these results, we concluded that the students had acquired the critical thinking skills, knowledge, and capacities taught within the pedagog-ical treatment. These data are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2

Summary of CCTST Pretest–Posttest Statistics

Parameter t(33) Cohen’sd r2

Total score 3.057a .534 (Medium) 22.07% (Strong) Percentile score 4.600a .789 (Large) 39.07 (Very strong) Analysis 1.521 .260 (Small) 6.55% (Medium) Inference 3.48a .598 (Medium) 25.85% (Strong) Evaluation 2.490b .427 (Medium) 15.82% (Medium) Inductive 3.730a .640 (Medium) 29.66% (Strong) Deductive 2.860a .491 (Medium) 19.87% (Strong)

aSignificant,α <.005.bSignificant,α <.01.

CRITICAL THINKING IN THE BUSINESS CLASSROOM 57

TABLE 3

Summary of Chapter Pretest–Posttest Statistics

Module t Cohen’sd r2

1. Introduction t(38)=2.72a .435 (Medium) 16.25% (Strong)

2. Memory and knowledge t(30)=1.807b .324 (Small) 9.81% (Medium)

3. Thought and language t(38)=2.673a .428 (Medium) 15.82% (Strong)

4. Deductive reasoning t(36)=5.03a .827 (Large) 41.30% (Very strong)

5. Analyzing arguments t(37)=3.224a .523 (Medium) 21.93% (Strong)

6. Thinking as hypothesis testing t(36)=3.526a .580 (Medium) 25.67% (Strong) 7. Likelihood and uncertainty t(32)=3.736a .650 (Medium) 30.37% (Strong)

8. Problem solving t(30)=4.403a .790 (Large) 39.25% (Very strong)

9. Decision making t(27)=1.996b .3772 (Medium) 12.86% (Medium)

Overall score t(312)=9.360a .535 (Medium) 22.28% (Strong)

aSignificant,α <.005.bSignificant,α <.05.

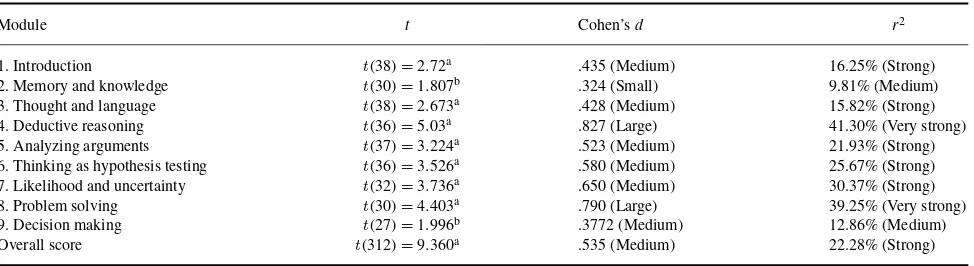

Chapter Pretests and Posttests

Because it was important to determine whether the content of each chapter of the critical thinking treatment had been ac-quired, retained, and recalled, the results of the pretest chap-ter quizzes from the experimental classes were compared to their corresponding posttests. The students’ scores in pretest and posttest of the chapter-by-chapter modules quizzes were

compared using a repeated measuresttest. In each module,

thetscores were found to be significant. In Modules 2 and

9, thetscores were found to be significant at the 95%

con-fidence level. In all other modules, thetscore were found to

be significant at greater than the 99.5% confidence level. The total of all the module scores was found to be significant at greater than the 99.5% confidence level. A summary of the data analyses are shown in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

The objectives of this study were to determine whether criti-cal thinking could be taught, whether it could be learned, and whether critical thinking skills could be transferred among domains. A treatment was developed that was congruent with Halpern’s Teaching for Critical Thinking model. The treat-ment was taught to two capstone classes in a college of busi-ness administration. Emphasis was placed on reconstructing the regular business-class case studies to incorporate a crit-ical thinking component to assess transfer. An independent, reliable, and validated assessment instrument was used to determine the acquisition, retention, and recall of critical thinking skills. Quizzes, designed by Halpern and Riggio (2003) for use with the textbook used in the treatment, were used to assess chapter-by-chapter learning.

Statistical analyses showed that six of the seven param-eters of the CCTST were shown to be significantly higher in the experimental classes than in the control class. These results were interpreted as evidence that the treatment had been effective in increasing the CT skills of the students in comparison to the regular, business class program of study.

Statistical analyses of chapter-by-chapter quizzes showed that the students’ scores at posttest were significantly higher than their scores at pretest. These results were interpreted as evidence of the students’ acquisition, retention, and recall of the information content within each chapter of the critical thinking textbook.

Statistical analyses of six of the seven parameters of the CCTST were shown to be significantly higher at posttest than at pretest. These results were interpreted as evidence of the student’s acquisition, retention, and recall of the critical thinking skills acquired during the treatment. These results were also interpreted as utilizing the skills initially learned within the domain of the critical thinking treatment and trans-ferred those skills successfully to the domain of the CCTST. The regular classroom instructor verified that the students had successfully used their CT skills in the analyses of their weekly business course case studies. The instructor also veri-fied that the students had used the CT skills they had acquired to assess the tactics and strategies employed in case studies of their assigned corporations. These results were interpreted as utilizing the skills initially learned within the domain of the CT treatment and transferred those skills successfully to the domain of business.

Therefore, the goals of this study were completed. It was shown that critical thinking can be taught. It was shown that critical thinking can be learned. It was shown that critical thinking skills can be transferred from one domain to another.

CONCLUSIONS

Case (2005) stated, “Every curriculum document mentions critical thinking, and there is universal agreement about the need to make thoughtful judgments in virtually every as-pect of our lives - from who and what to believe to how and when to act” (p. 45). The National Science Foundation has declared that the acquisition of critical thinking skills

are “. . .invaluable not only in science but also in making

wise and well-informed choices as citizens and consumers” (Grigg et al., 2007, pp. 7-3). The National Science Founda-tion concluded, “approximately 70 percent of Americans do not understand the scientific process, technological literacy is weak, and belief in pseudoscience is relatively widespread and may be growing” (Board, 2004, pp. 7-34). The National Mathematics Advisory Panel recommended, “assessments should be improved in quality and should carry increased emphasis on the most critical knowledge and skills leading to Algebra” (Flawn, 2008, p. xiv).

The results from this study indicate that a course devel-oped with behavioral–cognitive protocols, such as those pro-posed by Foshay et al. (2003), using Halpern’s principles, and developed for TCT, was effective in teaching critical think-ing skills to undergraduate seniors. These results demon-strate that critical thinking skills can be taught, learned, and transferred. Using Ken Silber’s nomenclature, the needle was moved!

This study also indicates that domain knowledge need not be required to learn critical thinking skills. Although we made efforts to integrate critical thinking skills within the business curriculum, the wide variety of questions and problem-solving skills required by the CCTST did not in-clude those of the domain of business or of the logical pro-cesses involved in the acquisition of critical thinking skills. These findings indicate that the students in this sample suc-cessfully acquired and then transferred the knowledge and skills they gained in the course of study to the CCTST as-sessment questions.

FUTURE RESEARCH

The need to teach and to learn critical thinking skills is ev-ident. This research indicates that a training course, such as the pedagogical treatment, is effective in teaching critical thinking skills to students. However, additional research is needed to confirm these results in other environments and to apply these results to the greater questions of education theory and practice. Halpern’s TCT conceptual model was chosen as the exemplar because it was well documented, in-cluding books, supplementary texts and numerous resources. However, other experts have written extensively on critical thinking. Research using their methods should be studied using validated assessment instruments.

The course of study included a wide variety of pedagogical techniques directed toward scaffolding to enhance metacog-nitive strategies and learning. It must be asked: Which, if any, enhanced learning? It has been reported that scaffolding is ineffective as an enhancement to learning (Su & Klein, 2008). Would students have learned just as much without any scaffolding?

The sample populations in this study were college seniors majoring in business administration at a single Midwestern university. Are the students of this university unique in

com-parison with other universities? Are business administration majors more or less proficient than college students major-ing in some other discipline? Are high school, junior high school, or elementary school students more or less capable of learning critical thinking skills than are college students? Is there a lower age limit below which instruction in critical thinking is ineffective?

This preliminary study has implications for the future of education. To comply with the recommendations of the U.S. Department of Education and improve high school graduates’ scores, students should learn critical thinking skills. To do so would require high school curricula incorporating critical thinking instruction. In turn, this would require teachers to become skilled in critical thinking theory and practice, as well as in the methods of teaching critical thinking. Because it is colleges of education that provide the basic training for teachers, how might this research affect their curricula in the future? Similarly, how might greater emphasis on critical thinking affect the business school curriculum?

REFERENCES

Abbate, S. (2008).Online case studies and critical thinking in nursing. Doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL. Bloom, P., & Weisberg, D. S. (2007). Childhood origins of adult

re-sistance to science. Science, 316(5827), 996–997. Retrieved from http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/316/5827/996 Brock, W. (1991).What work requires of schools. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Labor.

Case, R. (2005). Bringing critical thinking to the main stage.Education Canada,45(2), 45–46.

Clark, R., Yates, K., Early, S., & Moulton, K. (2006). An analysis of the failure of electronic media and discovery-based learning: Evidence for the performance benefits of guided training methods. In K. Silber & A. W. Foshay (Eds.),Handbook of training and improving workplace performance(Vol. 1, pp. 263–297). Somerset, NJ: Wiley.

Combs, R. (1992).Developing critical reading skills through whole lan-guage strategies. Retrieved from ERIC database (ED353556). Bethany OK: Foundation in Reading II, Southern Nazarene University.

Facione, N. C. (1997).Critical thinking assessment in nursing education programs: An aggregate data analysis. Millbrae, CA: California Aca-demic Press.

Facione, N. C., & Facione, P. A. (1997).Critical thinking assessment in nursing education programs: An aggregate data analysis. Retrieved from http://www.insightassessment.com/9books.html#NsqBook

Facione, N. C., Facione, P., Blohm, S. W., & Gittens, C. (2008).California Critical Thinking Skills Test: Test manual. Millbrae, CA: Insight Assess-ment.

Facione, P. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Research find-ings and recommendations. Retrieved from ERIC database (ED315423). Newark, DE: American Philosophical Association.

Facione, P. (2007).Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press.

Facione, P., Facione, N. C., & Giancarlo, C. A. (2000). The disposition toward critical thinking: Its character, measurement, and relationship to critical thinking skill.Informal Logic,20(1), 61–84.

Flawn, T. (2008).Foundations for success: The final report of the National Mathematics Advisory Panel. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Edu-cation.

CRITICAL THINKING IN THE BUSINESS CLASSROOM 59

Foshay, W., Silber, K., & Stelnicki, M. (2003).Writing training materi-als that work: How to train anyone to do anything. New York, NY: Wiley.

Giancarlo, C. A., Blohm, S. W., & Urdan, T. (2004). Assessing secondary students’ disposition toward critical thinking: Development of the Cal-ifornia Measure of Mental Motivation.Educational and Psychological Measurement,64, 347–364

Grigg, W., Donahue, P., & Dion, G. (2007).The nation’s report card: 12th-grade reading and mathematics 2005 (NCES007-468). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Halpern, D. (1984). Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Halpern, D. (1989). Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking (2nded.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Halpern, D. (1993). Assessing the effectiveness of critical thinking instruc-tion.Journal of General Education,42, 239–254.

Halpern, D. (1997).Critical thinking across the curriculum: A brief edi-tion of thought and knowledge. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Halpern, D. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American Psychologist,53, 449–455.

Halpern, D. (1999). Teaching for critical thinking: Helping college students develop the skills and dispositions of a critical thinker.New Directions for Teaching and Learning,1999(80), 69–74.

Halpern, D., & Nummedal, S. (1995). Closing thoughts about helping students improve how they think.Teaching of Psychology,22(1), 82– 83.

Halpern, D., & Riggio, H. (2003).Thinking critically about critical thinking (4thed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kane, M., Berryman, S., Goslin, D., & Meltzer, A. (1990).Identifying and describing the skills required by work: The Secretary’s commis-sion on achieving necessary skills. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor.

Kirshner, P., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential and inquiry-based teaching. Edu-cational Psychologist,41(2), 75–86.

Leppard, L. J. (1993). Classrooms: The confluence of essential social streams.Social Education,57, 80–82.

McKee, S. (1988). Impediments to implementing critical thinking.Social Education,52, 444–446.

Merrill, D. (2002). First principles of instruction.Educational Technology Research & Development,50(3), 43–59.

Merrill, D. (2007). A task-centered instructional strategy.Journal of Re-search on Technology in Education,40(1), 5–22.

National Science Board. (2004).Science and engineering indicators 2004 (NSB Publication No. NSB 02–1.) Washington, DC: National Science Foundation.

Phillips, C., Chestnut, R., & Rospond, R. (2004). The California Critical Thinking Instruments for benchmarking, program assessment, and direct-ing curricular change.American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 68(4), 1–8.

Reid, J. (2009a, October).Can critical thinking be learned?Paper presented at the Mid-West Regional Educational Research Association, St. Louis, MO.

Reid, J. (2009b).A quantitative assessment of an application of Halpern’s Teaching for Critical Thinking in a business class. Doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL.

Rosaen, C. (1988).Interventions to teach thinking skills: Investigating the question of transferRetrieved from ERIC database (ED304678). Wash-ington, DC: Office of Educational Research and Improvement. Shettle, C., Roey, S., Mordica, J., Perkins, R., Nord, C., Teodorovic, J.,

. . .Kastberg, D. (2007).The nation’s report card: America’s high school graduates(NCES 2007-467). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Su, Y., & Klein, J. (2008, October).The impact of scaffolds and prior knowledge in a problem-based learning environment. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association of Educational Computers and Technology, Orlando, FL.

Tiwari, A., Lai, P., & Yuen, K. (2006). A comparison of the effects of problem-based learning and lecturing on the development of students’ critical thinking.Medical Education,40, 547–554.

Vermunt, J. (1996). Metacognitive, cognitive and affective aspects of learn-ing styles and strategies: A phenomenographic analysis.Higher Educa-tion,31(1), 25–50.

Westbrook, S. L., & Rogers, L. N. (1991, April).An analysis of the re-lationship between student-invented hypotheses and the development of reflective thinking strategies.Retrieved from ERIC database (ED340605). Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Lake Geneva, WI.

Whetzel, D. (1992).The Secretary of Labor’s commission on achieving nec-essary skills. Retrieved from ERIC database (ED339749). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor.

Willingham, D. T. (2007). Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach? American Educator, Summer, 8–19.

Winn, I. J. (2004). The high cost of uncritical teaching.Phi Delta Kappan, 85, 496–497.