Barista’s Battle Scars

Susan M. Jensen

Srivatsa Seshadri

Larry G. Carstenson

This case tells the story of an entrepreneur couple who launched an upscale retail coffee business in a mid-sized college town in the Midwest. Barista’s enjoyed immediate and overwhelming market acceptance and was even named “Entrepreneur of the Year,” yet had tremendous difficulty in obtaining expansion capital. The choice of legal advisor also proved to have enormous impact on the future viability of the business. Written from the perspective of the entrepreneurs, the case provides unique insight regarding the importance of cultivat-ing the effective professional relationships needed for business success.

Act One, June 2001: The Eternal Line at the Drive-Through

“We can never close!” Kelly1

realized, with a mixture of wonder and dread. As she worked feverishly to fill orders, Kelly watched the line of cars waiting to be served stretch across two city blocks. Since opening 6 months ago with a loan from Community Bank, sales had been booming at the drive-through coffee shop. With its distinctive European design, unique products, and commitment to personalized service, Barista’s had quickly built a reputation as the quality place for gourmet coffee.

Kelly felt so proud to have realized her dream of creating a drive-through setting that mirrored the experience of an upscale sit-downindoorrestaurant, with beautifully tended gardens, waterfalls, and soft music coming from outdoor speakers. The shop was built on a small plot of land that was surrounded on all sides by other businesses. She utilized her prior experience as an interior designer to create a uniquely welcoming location (see Figure 1). No impersonal, scratchy loudspeaker ordering system here; instead, Kelly and her staff fostered a close interaction with customers by taking their orders face to face at the window. And no operating hours were posted. The business operated on the policy that “if the lights are on, the business is open.” Kelly chuckled as she recalled how she spent months selecting the right type of equipment for the new business but had forgotten all about buying a “closed” sign for the store. That oversight actually offered Kelly great opportunity, especially since she had been confident there was unmet demand for “after-dinner” coffee in this Midwestern college town of 40,000 people. Barista’s was one of the very first coffee shops in the region, so Kelly found herself educating customers (who

Please send correspondence to: Susan M. Jensen, tel.: (308) 865-8189; e-mail: jensensm1@unk.edu. This case was presented by the authors at the Midwest Academy of Management Conference, St. Louis, Missouri in September 2008.

1. Names, years, and months have been disguised to protect the entrepreneurs from any legal problems from their ex-attorney as a result of publicizing their experiences, however remote such a possibility might be. The progression of the case, however, is authentic.

P

T

E

&

1042-2587

© 2012 Baylor University

typically viewed coffee as a “morning” drink and were most familiar with coffee brewed at home or available at gas stations) on the different qualities and types of coffee. Barista’s not only offered a wide variety of coffees, but also specialty teas, cocoas, fruit smoothies, Italian sodas, organic juices, pastries, shortbreads, and organic food bars. Kelly created a “happy hour” from 5 to 7pmto build awareness of different “after dinner” drinks. At first,

sales in the evening were slow, but it did not take long before traffic was steady throughout the day and night. Kelly just continued to extend the operating hours, and customers soon discovered they would be served any time the lights were on, day or night. Of course, that meant somebody needed to serve those customers, day or night!

Kelly had initially chosen a drive-through facility since she was convinced most of us seem to live in our cars. But now customers drawn in by the beautiful surroundings were asking for a place to sit down and enjoy their coffee and the gardens, and Kelly noticed people often parked on streets nearby to drink their coffee. While space was limited, Kelly installed a bike rack and a few benches by the waterfall, which always seemed to be occupied.

Her customers’ eagerness to linger and savor their coffee (as well as their patience in waiting for their custom order to be freshly prepared) gave Kelly a great sense of satisfaction. Barista’s was quickly establishing a reputation as a distinctive specialty coffeehouse, and customers appreciated the art and skill involved in crafting the perfect cup of coffee. Kelly’s skilled staff did not simply flip open a coffee pot tap and fill a mug—they took the time needed to blend delicious brews, use proper foaming techniques, and even create unique “coffee art” (e.g., pouring steamed milk into a piping hot cup of espresso and generating a rosette design on the surface) to delight customers.

Figure 1

During the next few months, revenues continued to grow steadily, with sales revenue more than 10% above what Kelly had expected. Her pride at achieving success beyond expectations in such a short period of time was tempered by both pure exhaustion and concern about how to capitalize on this growing demand—especially since Kelly had invested nearly $40,000 (a huge chunk of her savings) to launch the business. Kelly took a deep breath, gave her head a little shake, and told herself to practice the advice she gave to her staff: “Don’t look at the end of the line . . . just look at the next car.” Still, Kelly knew she needed to look ahead to determine the future of Barista’s.

How could she manage the seemingly eternal rush of cars? Was it time to consider expanding the business . . . and if so, how?

Act Two, October 2001: Time to Educate Bankers, Not Just Customers

Ten months to the day that Barista’s had opened its doors, Kelly stormed out of Community Bank, holding back tears of frustration. She had just spent the last hour explaining her plans to expand the business by opening a second location in the downtown shopping area. After an exhaustive search, Kelly and her business partner, Bob Jones, had found the perfect spot. This location would not only have a drive-through, but also a large outdoor patio, indoor seating, and ample space for future expansion (see Figure 2 for a sketch of the proposed new location). Keeping with the “landscape as a billboard” approach, Kelly was confident this downtown location would best meet the customers’ needs, as they could drive through for their morning coffee, meet at the patio in the afternoon or evening, and enjoy their beverages indoor by the fireplace on chilly days. The downtown site would also be appealing to patrons of nearby stores, theatres, and museums.

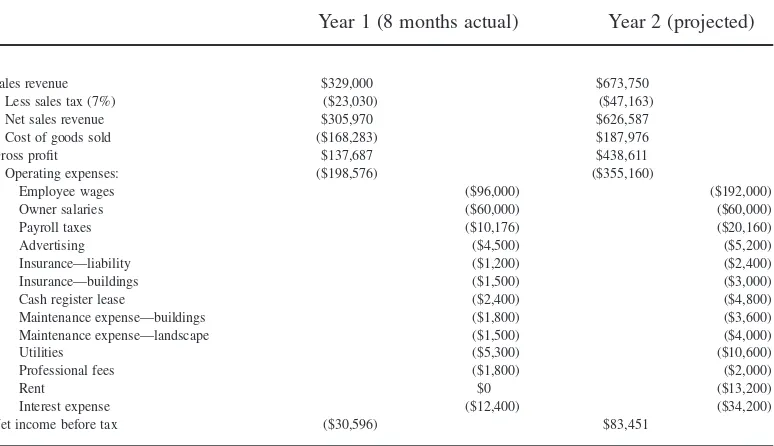

Kelly had arrived at the bank with her business plan outlining the expected costs, design, and anticipated sales associated with the expansion and had worked hard to write a clear and concise executive summary of the plan (see Appendix). With nearly $40,000 as her original owner investment, she requested a loan of $290,000 to be used for building construction, landscaping, purchase of equipment and fixtures, and working capital. Kelly had initially borrowed $158,000 to launch the business, so this additional loan would increase her outstanding debt to the bank to a total of 488,000. Traffic at the original

Figure 2

drive-through location continued to be so overwhelming they had begun a free delivery service as a way to help shorten the queue and wait time, and their loyal customers kept urging them to open another location. Strong demand for premium coffee was evident, as Barista’s was now one of seven coffee shops in town. Barista’s marketing approach, which included a “frequent guest card” and visible support for the local children’s museum and other activities, had helped to heighten awareness and generate a loyal customer base. Kelly was also armed with Barista’s historical financial statements depicting that strong sales volume (see Table 1). “The banker laughed when we told him we would generate $300,000 in sales our first year . . . and we actually had $329,000 in sales!” Kelly recalled with pride as she prepared for the meeting that morning. But her hope that the lenders at Community Bank would share that excitement was quickly dashed.

As the meeting began, Cal Smith, the Vice President of Community Bank who had been recently assigned to the Barista’s account, was cordial but cool. After reviewing the information Kelly provided and listening to her plans for the new location, he stated, “Well, Kelly—it does look like you met your first year’s sales projections, but you haven’t shown a profit yet, and your gross margins are way below the industry averages for restaurants. The wages you are paying your employees are much too high.” Kelly tried to explain that Barista’s should not be considered a restaurant, since the employees are highly trained and earn nearly $10 per hour (the industry average for baristas), as compared with the typical restaurant server who relies primarily on tips as their hourly pay is well below the minimum wage. But Cal simply responded “Restaurant industry aver-ages are the closest we have to use for comparison, and your business just doesn’t compare well. We use the Robert Morris AssociatesAnnual Statement Studies book as our refer-ence, which shows an average gross margin for restaurants of 60%, compared to your gross margin of just 45%.2Besides, you’ve only been in operation for a year, so it’s just

too soon to think about expanding, especially since you already pledged all your assets as security for your first loan. And your design for this new location seems to include an awful lot of “fluff” that isn’t really needed. Why, you want $35,000 just for landscaping? That is odd and unrealistic.” Trying hard to keep her temper in check, Kelly responded, “If you come by our business any time of the day, you’ll see the tremendous demand for our products. As the first gourmet coffee shop in town, we’ve transformed skeptical people who considered coffee a cheap commodity into loyal customers who understand and appreciate our specialty products and service. And that ‘oddness’ of Barista’s, with attention paid to the surroundings and ambience, is what has made us so successful and created such passion in our employees and customers. I know you’ve always told me you’re not a coffee drinker, and you have never taken us up on the invitation to stop by for some free samples. But if you did, you would see how the demand for our business is really growing in this region. We need to expand and take advantage of that growth, or else be left behind.”

As she walked to her car after the meeting, Kelly was dumbfounded that after all the information she had shared, Cal simply led her to the door stating “maybe after you’ve been in business for another year or two, we can consider your expansion plans. But as of now, Community Bank won’t extend any additional financing to Barista’s.” How in the world could she convince the bank that the time to expand was now, not later? She had helped educate customers about the gourmet coffee industry; why couldn’t she seem to educate the banker? Kelly thought back to the countless hours she had devoted to the business this past year. Nobody spent more

Table 1

Income Statement—Actual 1st Year Operations and Year 2 Projections

Year 1 (8 months actual) Year 2 (projected)

Sales revenue $329,000 $673,750 Less sales tax (7%) ($23,030) ($47,163) Net sales revenue $305,970 $626,587 Cost of goods sold ($168,283) $187,976 Gross profit $137,687 $438,611 Operating expenses: ($198,576) ($355,160)

Employee wages ($96,000) ($192,000) Owner salaries ($60,000) ($60,000) Payroll taxes ($10,176) ($20,160) Advertising ($4,500) ($5,200) Insurance—liability ($1,200) ($2,400) Insurance—buildings ($1,500) ($3,000) Cash register lease ($2,400) ($4,800) Maintenance expense—buildings ($1,800) ($3,600) Maintenance expense—landscape ($1,500) ($4,000) Utilities ($5,300) ($10,600) Professional fees ($1,800) ($2,000) Rent $0 ($13,200) Interest expense ($12,400) ($34,200) Net income before tax ($30,596) $83,451

Proposed sources and uses of funds:

Sources: Uses:

Owner investment $26,000 Leasehold improvements $220,000 Bank loan $290,000 Landscaping $35,000

Total sources $316,000 Equipment/fixtures $40,000 Inventory $5,000 Working capital $16,000

Total uses $316,000

Balance sheet (as of August 31, 2001)

Assets Liabilities and equity

Cash $7,500 Accounts payable $44,296 Inventory $6,200 Long-term debt $158,000

Total current assets $13,700 Total liabilities $202,296

Fixtures/equipment $28,000 Initial investment $40,000 Real estate $170,000 Year 1 earnings ($30,596)

Total fixed assets $198,000 Owner’s equity: $9,404 Total assets $211,700 Total liab. & equity $211,700

time in the business than she did and, frankly, she knew the business and industry far better than anyone else, including the banker! Bob had less of a hands-on role in the daily operations of Barista’s; he had kept his full-time job so they would not be solely dependent on the new business for their income. Bob played a key strategic visioning role, however, and Kelly always valued his keen business sense. She and Bob both knew in their hearts that the time for expansion was now, and they must be proactive or lose their competitive advantage. How could they get the banker’s support? When Kelly and Bob had first started Barista’s, they had borrowed $158,000 from Community Bank since Bob had banked there for years. In fact, they hadn’t taken their funding proposal anywhere else, and had just accepted Community Bank’s terms without question.

Why did the banker not share her excitement about market opportunities? How could she find a banker who understood the industry and was willing to help Barista’s grow now? What other funding options might exist?

Act Three, June 2002: Popularity Creates New Problems

As Kelly sat in the patio garden of the downtown Barista’s, she reflected back on the frustration she had endured the previous year when trying to obtain additional financing from Community Bank. Irritated because their banker had never set foot in the business, nor been willing to learn about the gourmet coffee industry, Kelly had left that meeting a year ago determined to expand, with or without bank support. And, as she gazed about the new location, filled with customers chatting and enjoying the gor-geous summer evening, Kelly realized her determination had proven rather costly. “We did make some poor choices, such as cashing in our retirement accounts (and paying a $30,000 penalty) and maxing out our credit cards. But it seems to have been worth it,” she mused. Kelly and her business partner, Bob, had considered the possibility of bring-ing in an outside investor but were afraid nobody else would truly share their vision. So they scraped together all they could of their own money and proceeded with the expan-sion plans for a combined drive-through and a sit-down coffee place, including the upscale design and landscaping that the banker had considered to be unnecessary “fluff.” The bank considered them foolish, and the construction of the new location was a hot topic of conversation in town as the tile roof, brick patio, water fountains, and extensive gardens made the downtown Barista’s the most unique (and, some argued, most expensive) building in the county. Although Kelly liked to say they “paid the price of being pioneers” in the gourmet coffee business, the steady flow of customers at both their locations, despite the opening of two Starbucks locations and a Caribou Coffee in town, proved that the risk was worthwhile. Annual sales volume now exceeded $670,000, and just as customers had urged Kelly to create another location in town, customers who came from across the state and even from neighboring states were now telling Kelly, “we need one of these Barista’s in my home town!” Kelly was excited about the idea of expanding Barista’s to other cities but was not sure how to finance or manage more locations.

She was now pondering how to prevent these “copy-cats.” Having exhausted all of her and Bob’s personal finances, she had few financial resources to open her outlets in other towns and move in before other competitors established their presence.

What alternatives did she have? How could she prevent others from stealing her idea?

Act Four, October 2002: Barista’s Achilles’ Heel?

Franchising appeared to be a viable way to expand the business and hopefully protect their business concept. Kelly had purchased a book about franchising and talked to her contacts in the Specialty Coffee Association of America, the trade association that had been a wealth of information ever since Kelly first considered starting a gourmet coffee business. As she researched franchising, Kelly still needed a banker who understood the coffee business. Who would have dreamed one could find a bank by purchasing a bag of coffee beans? Several months earlier, still stinging from her frustrating attempts to educate the local bankers, Kelly tried a creative way to identify banks familiar with the coffee industry. She purchased a bag of beans from The Grist, the very first coffee shop in the Midwest, located approximately 300 miles from her store. Kelly paid for the beans by personal check, and when the check cleared she could tell from the imprint on the back that the check was processed by Commerce Trust. Kelly then contacted Commerce Trust and, after a few short phone calls, had a banker who was enthusiastic (and informed) about opportunities for Barista’s.

However, Kelly soon had to grapple with another challenge. How could she find someone to help create and promote a franchise? Kelly had contacted a lawyer who was a family friend, but he told Kelly he was not familiar with franchising and suggested she and Bob check the websites of various firms to find attorneys with franchising expertise. She followed his advice and found Olsen & Olsen, a local firm whose website touted its experience in franchising. Kelly and Bob asked people in the community who had worked with this firm, and all the clients of Olsen & Olsen with whom they spoke gave the firm glowing reviews. With the help of an attorney from Olsen & Olsen, a new franchising division (wholly owned by Kelly and Bob) was created: Barista’s & Buddies.

Just months after the downtown location was open, the first franchise was sold. Soon others followed. The cash flow generated from selling franchises (which included a $45,000 initial franchise fee and 4% royalty rate) made it possible for Barista’s to substantially increase its market reach. Kelly was, however, disturbed by a telephone conversation she had with a prospective franchisee in March. Kelly remembered him saying that his lawyer indicated the franchise documents did not satisfy Federal Trade Commission standards and suggested he not sign the franchise documents, but he went ahead and signed. Something about this conversation kept nagging her. Kelly realized she had placed a great deal of trust in her attorney.

What steps should Kelly take now to address her concern about the conversation with the prospective franchisee?

Act Five, December 2004: The Devil Is in the (Franchising) Details

Two years after the first franchise was awarded, the franchise division of Barista’s & Buddies included 21 franchises in three states. Kelly was proud not only of their success in obtaining eager franchisees, but also that Barista’s had recently been recognized as the state’s “Entrepreneur of the Year” by the Small Business Administration. What an honor and validation of their ideas and hard work! As she held the letter from the FTC, however, she felt nothing but fear. In no ambiguous terms, it demanded Barista’s & Buddies cease and desist franchising activity as the company was faced with the very serious legal charge of fraud. What was she to do? She and Bob had invested their life savings in this venture, and now this?!

Kelly recalled that troubling phone call from a franchisee a year ago who had challenged the validity of the franchise document. At that time, the franchisee told Kelly that his attorney had advised him to not sign any documents, as they did not satisfy FTC standards. That franchisee, however, had been so impressed with the Barista’s concept and the hands-on approach Kelly used to select franchisees, he opted to sign the contract despite his lawyer’s concerns. Immediately following that phone conversation with the franchisee, Kelly had contacted her franchise lawyer for clarification. This attorney had been selected based on information on his firm’s website touting his franchise expertise, and he reassured Kelly that the documents were fine. According to the FTC, however, the franchises were, in fact, illegal! It appeared that the franchisee who told Kelly that his lawyer advised him not to sign the documents was right! Now, a year later with the FTC letter in hand, Kelly again called her franchise attorney. Once again, he reassured Kelly that she had nothing to worry about and that he would take care of it. Kelly hung up the phone, feeling only a little less worried.

Kelly also had another troubling issue demanding her attention at the time. A few weeks prior, Barista’s & Buddies had decided to revoke a franchise. This franchise was owned by a man in a neighboring state who appeared to have ulterior motives. Kelly and her business partner, Bob, were uncomfortable with how this franchisee would bring groups of people to tour the Barista’s downtown location, always without permission and while Kelly and Bob were out of town. Further investigation indicated this franchisee was opening his own chain of coffee shops and appeared to be using Barista’s as a training and idea generation source, contrary to the spirit of the franchise agreement. The decision to revoke the franchise was a difficult one for Kelly, as she prided herself in “building relationships and being able to assess people’s character.” Yet within weeks of revoking this franchise, Kelly now stood with this letter in her hand, claiming the franchises were illegal and rescission payments were due each franchisee. Her heart racing, she asked herself: Was there some connection between the revoked franchise and this FTC letter?

Appendix

Executive Summary of Barista’s Business Plan—September, 2001

(Presented to Community Bank when requesting funding for expansion to downtown location)

Nothing beats a great cup of coffee; it’s the American way. Some of us drink coffee in the morning and some of us drink it all day long. As a matter of fact, decaf coffee drinkers make up a considerable portion of the market, starting with caffeinated beverages in the morning and switching to decaffeinated for the remaining part of the day and evening. The National Coffee Association reports that 80% of adults over 18 drink coffee on a daily or occasional basis. Year-over-year coffee consumption continues to grow at an average of 12.8%. Great coffee and espresso drinks are a staple in many countries and are now accelerating in popularity across America. Sixty-two percent of adults report drinking gourmet coffees on a regular or occasional basis, and 14% drink gourmet coffees daily. We are learning to appreciate and understand coffee and tea in very much the same way we appreciate select wines and fine foods. Barista’s offers customers a selection of beverage choices that not only include espresso drinks, but teas, smoothies, juices, Italian sodas, and all-natural health and energy drinks. We also feature freshly prepared pastries and snacks.

Barista’s provides more than just a great cup of coffee. Imagine a stucco covered villa covered with a curved Italian tile roof, awnings, hanging baskets of flowers, inviting landscaped and lawn areas, old brick paths, and a place to sit and enjoy a friends’ company [see Figure 1]. That’s Barista’s and we’re so much more than a “drive thru.” Our business approach is diverse providing drive-thru espresso for convenience, a sit down patio for relaxation and the ability to purchase retail items. Customers enjoy our full menu of products from a walkup window. These amenities are surrounded by a beautiful outdoor courtyard designed to appeal to all of your senses. We also understand that it’s critical that every experience meet our customer’s expectations. All employees receive intensive training, which includes beverage preparation and equipment use, as well as customer service training

The tremendous popularity of our drive-through location demands that we expand our operations to a second location. Based on feedback from customers, a larger facility with indoor dining and relaxing outdoor patio is needed and would be well received. An ideal site has been located in the downtown region. This location has great visibility, ready access to parking, and is located near the Museum of Art and other boutiques which appeal to Barista’s customers. We plan to lease the location and construct a building onsite. Start-up costs for this location are estimated to be $316,000 resulting in estimated first year sales of between $449,000 and $673,000, and an estimated net profit of $49,440– $110,185. We are seeking a loan in the amount of $290,000 which will be used for building construction, landscaping, purchase of equipment and fixtures, and working capital. The remainder of the new location start-up costs will be funded by our personal investment.

Susan M. Jensen is an Associate Professor of Management at University of Nebraska at Kearney, College of Business and Technology, Kearney, NE.

Larry G. Carstenson is a Professor of Business Law at University of Nebraska at Kearney, College of Business and Technology, Kearney, NE.

The authors wish to express their deep gratitude to the entrepreneurs for their willingness to not only share their story but also to relive their painful experience while sharing their story.

Note to Instructors Belonging to Teaching Case “Barista’s Battle Scars”

This case presents a true-life (albeit disguised) account of an entrepreneur couple’s experience of optimism, success, frustration, and mistakes. This case demonstrates the challenges entrepreneurs face in managing growth and building the professional relation-ships needed for business success. The importance associated with educating consumers and professionals (including bankers, accountants, and lawyers) about the potential of the gourmet coffee industry is also highlighted.

Case studies often document a successful application of all aspects of business strategy. Learning from the successes of others can be valuable; however, the lessons that can be learned from cases highlighting unsuccessful business practices are far more useful (Abraham & Brajac, 1997). Focusing on the causes of failure has, for example, resulted in significant improvements in both the airline and healthcare industries. Unfortunately, public dissemination of information regarding failed businesses is limited. Rarer still are cases that highlight a business like Barista’s, which appears to be successful and a model for others, and was even the proud recipient of the state’s “Entrepreneur of the Year” award. Yet after a short life span of just 48 months (and just 1 year after having won that award), the owners of Barista’s face the heart-wrenching decision of having to potentially shut down the business. The case is written in sequential “acts” that demonstrate the evolving challenges faced by the entrepreneurs involved in Barista’s. The executive summary and financial section of the business plan created by the owners when they were seeking expansion financing are provided as exhibits following the case. The entire business plan is also provided as part of the Teaching Note.

Key Issues and Discussion Points

The case focuses on the creation and potential demise of a specialty coffee retailer and highlights the challenges faced by the entrepreneurs as they managed growth and estab-lished the professional relationships needed for business success. Each “act” concludes with questions the entrepreneur must address (and reflects the actual issues that “Kelly and Bob” were grappling with at that time). Key issues and points for class discussion include:

1. the need for an entrepreneur to not only have a passion for the business, but also the ability to convey the business potential to key stakeholders (such as bankers, accountants, and lawyers) and to understand the unique needs and concerns of those stakeholders;

2. the importance of due diligence when selecting professionals who will be involved as advisors in the enterprise;

3. ways to engage in relationship marketing with customers and transform a perceived commodity into a specialty product;

4. understanding the product is more than the core offering (coffee) and includes intan-gibles such as the appearance of the store, friendliness of staff, etc.; and

Potential Uses

This case can be used to illustrate the decisions faced by entrepreneurs regarding (1) expansion and modes of expansion; (2) judicious choice of creditors and service provid-ers; and (3) the painful emotional and financial costs faced by entrepreneurs even when their business is well accepted by the marketplace. Additionally, it can used to demon-strate the role of creativity in differentiating a commodity product in ways beyond just branding.

Potential Audience

This case has direct potential for entrepreneurship, small business management, and new venture marketing courses, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. Addition-ally, the case can be used in workshops directed toward nascent entrepreneurs. It also highlights issues commonly addressed in strategic management courses, as well as more specialized classes in entrepreneurship programs focusing on new venture financing and intellectual property.

Suggested Teaching Approach

With its rich and complex content, the Barista’s story has been discussed in each of the co-authors’ classes, which include entrepreneurship, marketing, and business law, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

Users of this case can apply a variety of pedagogical techniques. The case is written in sequential “acts” to expand the ways it can be used in various courses. Small business management and entrepreneurship classes might wish to use the entire case, or simply use some acts as background information and select one act as the primary focus (e.g., use Act Four to examine the advantages and disadvantages of franchising). The executive summary and financial section of the business plan prepared by the entrepreneur are provided as Appendix and Table 1 to offer additional richness for analysis and discussion, and the plan in its imperfect entirety is also included as part of the Teaching Note. Instructors wishing to focus on accounting and financing aspects could also find the financial statements included in the business plan useful for analysis, and might wish to assign students the task of developing their own projected financial statements, perhaps using more conservative estimates than those shown in the business plan. Please note that this business plan (while modified slightly to retain confidentiality) reflects the imperfect document originally created by Barista’s owners. Instructors may wish to challenge students to critique this “real life, messy business plan” and offer suggestions for improve-ment, and/or invite local lenders to speak to students about how a lender would critique this plan. Suggested guidelines for these forecasting and business plan critique assign-ments are included in the Teaching Note. Also included in the Teaching Note are guide-lines for additional supplemental assignments, including a SWOT analysis, product life analysis, and industry analysis.

undergraduate seminar or a graduate level course or a workshop targeted toward nascent entrepreneurs. Each act of the case offers opportunity for reflection and consideration of “What should Kelly and Bob do now?” and “What might they have learned from this experience?” The Teaching Note also offers some additional reflection questions beyond those provided at the end of each act in the case.

Finally, students can be asked to submit a one-page reflective paper on what they learned from the experiences of the entrepreneurs. This latter method was used by one of the authors in executive MBA classes taught in Europe, with excerpts of those MBA students’ responses included in the Teaching Note.

Role of the Authors

All events and individuals in this case are real. Information has been disguised to protect proprietary interests without compromising the learning value of the case. The entrepreneur featured in the case, Kelly, was a frequent guest speaker at the entrepreneur-ship class taught by one of the co-authors. All three co-authors were customers of Barista’s. When Barista’s troubles became the focus of local media, the co-authors approached Kelly to better understand what had transpired to this seemingly very suc-cessful business. Kelly eagerly agreed to share her story with the authors so others could learn from her experiences and mistakes. Kelly worked closely with the co-authors in the development of the case.

Outside or Supplementary Readings

Abraham, B. & Brajac, M. (1997). Real experiments, real mistakes, real learning. In S. Ghosh, W.R. Schucany, W.B. Smith, & D.B. Owen (Eds.), Statistics of quality (pp. 121–136). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Publications.

We used this article as supplementary reading in an EMBA class to focus on the concept that there is much to learn from mistakes. The greatest insight the EMBA students gained from this reading was that while learning from mistakes is a cliché, it cannot be accomplished if there is no transparency, and transparency cannot occur if there is fear of reprisals. The willingness of Kelly to go public with the mistakes they committed was seen by the students as an act of generosity and community service. Furthermore, they generally concluded that learning from mistakes is much more significant than learning from the successes that are related in most case studies. As Narayan Murthy, Chairman of Infosys India, said to graduating students in his graduation address to New York Univer-sity on May 9, 2007, “It can be much more difficult to learn from success than from failure. If we fail, we think carefully about the precise cause. Success can indiscriminately reinforce all our prior actions.”

Adam, D. (2009). With less computing power than a washing machine. Available at http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2009/jul/02/apollo-11-moon-technology-engineering, accessed 12 August 2009.

difference between survival and demise, between life and death. Additionally, the students became acutely aware that multiple mistakes in business (such as attempting aggressive growth, choosing the wrong attorney, and taking on all liabilities of the business) can combine multiplicatively, not summatively, to create a “tsunami” for an entrepreneur.

Adamy, J. (2008, January 7). McDonald’s takes on a weakened Starbucks—food giant to install specialty coffee bars, sees $1 Billion business.Wall Street Journal, p. A1. Ruggles, R. (2006, May 8). Coffee margins heat up, inspire gourmet-brew binge among QSRs.Nation’s Restaurant News, pp. 6 and 121.

These two articles describe the efforts of McDonald’s and other firms to poach Starbucks’ customers, and provide students an overview and future prospects of this industry. Experts argue that “cups continue to runneth over with upgraded premium and higher-quality coffees at quickservice restaurants” and forecast that “premium coffees, following demographic trends, will continue to percolate.” Starting in 2008, MacDonald’s installed coffee bars in nearly 14,000 of its U.S. restaurants, with “baristas” serving cappuccinos, lattes, mochas, and the Frappe, similar to Starbucks’s ice-blended Frappuc-cino. Burger King has introduced premium coffee, as have smaller chains such as the 460-unit Del Taco of Lake Forest, California. Coffee bean behemoth Dunkin’ Donuts, which serves 2.7 million cups a day, extended its coffee and espresso lines with new gourmet offerings. These articles provide students an idea of the lucrativeness of this industry. In the EMBA class, one of the authors used these articles as part of an assignment that required students to apply Porter’s 5-forces model of competitive forces to the coffee-beverage-serving industry.

Feld, B. (2004, March 24). The entrepreneur’s financial fitness checklist.Business Week Online.

While creating a growth business can be exhilarating, many entrepreneurs, especially those starting a company for the first time, do not pay enough attention to some of core issues surrounding the financial management of their businesses. This article offers a checklist that students can use when analyzing the case to evaluate Kelly’s business plan and her financial fitness.

Field, A. (1999, May). Getting the bank to yes.Success, 46, 67–71.

This article lists the basic questions that most bankers ask before approving business loans and which should be addressed in the business plan: expected cash flow, experience of the entrepreneurs, entrepreneurs’ current assets, break-even analysis, staffing plans, other investors sharing the risks, and credit history of the entrepreneurs. Instructors can use this article and ask students to create a checklist that banks can use to approve small-business loans, thus placing students in the role and mindset of a small-town banker. One of the authors had students use this article to develop questions to ask local lenders who were guest speakers.

Gray, S. (2005, April 12). Coffee on the double.Wall Street Journal, p. B1.

operations said, “This is a game of seconds,” adding that she and her team of 10 engineers are constantly asking themselves, “How can we shave time off this?” For example, a few years ago, engineers noticed that “baristas”—the Starbucks employees who prepare drinks—had to dig into ice bins twice to scoop up enough ice for a Venti-size cold beverage. “The old Venti scoop didn’t give you enough ice,” Ms. Peterson says. Engineers experimented with ceramic coffee mugs, which then led them to develop one-piece plastic “volumetric ice scoops.” But the handles kept breaking, so engineers had stronger ones made. The new scoops helped cut 14 seconds off the average preparation time for blended beverages of about 1 minute.

Mackey, J. & Valinkangas, L. (2004). The myth of unbounded growth.Sloan Management Review,Winter, 89–92.

There is a deeply held assumption that neither a company nor its management is viable unless it is able to grow. Growth gives investors a feeling that management is doing its job. Growth is typically perceived as a proactive (rather than a defensive) strategy. Or maybe, as the Red Queen says in Lewis Carroll’sThrough the Looking Glass, “Here it takes all the running you can do to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!” The authors had graduate-level students discuss this article to help them understand why Kelly was so eager to grow the business so quickly.

Politis, D. & Gabrielsson, J. (2009). Entrepreneur’s attitudes toward failure: An experi-ential learning approach.International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 15(4), 364–383.

This article has helped students gain a unique perception of entrepreneurs who fail. Most importantly, students realize there is much to learn from failure. The authors employ theories of experiential learning to examine why some entrepreneurs have developed a more positive attitude toward failures compared with others. Empirical findings support the guiding proposition that more favorable attitudes towards failing can be learned through entrepreneurs’ life and work and previous start-up experience is strongly associated with a more positive attitude toward failure. Moreover, the authors found that experience from closing down a business is associated with a more positive attitude toward failure. These research findings add to our knowledge of why some entrepreneurs have a more positive attitude toward failures compared with others. It also provides some general implications for our understanding of entrepreneurial learning as an experiential process.

Spors, K. (2009, February 23). So, you want to be an entrepreneur?Wall Street Journal. Small Business Report.

This article lists 10 questions to ask to see whether one is up for the challenge of entrepreneurship. In particular, it addresses the ability to bear financial risks. The authors have used this article to help undergraduate students explore the potential advantages and disadvantages of business ownership.

Sull, N.S. (2007, June 16). So you’re ready to seize that business opportunity?Wall Street Journal Online.