Series Editor: Ann R. Hawkins

Titles in this Series

1 Conservatism and the Quarterly Review: A Critical Analysis Jonathan Cutmore (ed.)

2 Contributors to the Quarterly Review: A History, 1809–1825 Jonathan Cutmore (ed.)

3 Wilkie Collins’s American Tour, 1873–1874 Susan R. Hanes

Forthcoming Titles

Negotiated Knowledge: Medical Periodical Publishing in Scotland, 1733– 1832

Fiona A. Macdonald

On Paper: Th e Description and Analysis of Handmade Laid Paper R. Carter Hailey

Reading in History: New Methodologies from the Anglo-American Tradition Bonnie Gunzenhauser (ed.)

Charles Lamb, Elia and the London Magazine: Metropolitan Muse Simon Hull

ENGRAVING

by

Mei-Ying Sung

london

© Pickering & Chatto (Publishers) Ltd 2009 © Mei-Ying Sung, 2009

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Sung, Mei-Ying

William Blake and the art of engraving. – (Th e history of the book) 1. Blake, William, 1757–1827 – Criticism and interpretation

I. Title 769.9’2

ISBN-13: 9781851969586

21 Bloomsbury Way, London WC1A 2TH 2252 Ridge Road, Brookfi eld, Vermont 05036-9704, USA

www.pickeringchatto.com All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise

without prior permission of the publisher.

∞

Th is publication is printed on acid-free paper that conforms to the American National Standard for the Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Abbreviation vi

List of Figures vii

Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 1 Th e History of the Th eory of Conception and Execution 19

2 Th e Evidence of Copper Plates 45

3 Blake’s Engraved Copper Plates 61

4 Copper Plate Makers in Blake’s Time 119

5 Blake’s Virgil Woodcuts and the Earliest Re-engravers 141 Conclusion 165 Notes 169

Works Cited 199

– vi –

Locations & Collections:

Beinecke: Beinecke Library, Yale University, New Haven CT, USA Bodley: Bodleian Library, Oxford University

BL: British Library, London BM: British Museum, London

BMPD: British Museum, Prints & Drawings Room Cleverdon: Douglas Cleverdon private collection

ESSICK: Robert Essick’s collection, Los Angeles CA, USA (to diff erentiate from Essick’s works)

FMC: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Fogg: Fogg Museum of Art, Harvard University, Boston MA, USA Houghton: Houghton Library, Harvard University, Boston MA, USA Huntington: Huntington Library, San Marino CA, USA

Leeds: Brotherton Library, Leeds University

Lewis Walpole: Lewis Walpole Library, Farmington, Yale University, CT, USA McGill: McGill University, Montreal, Canada

NGA: National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, USA Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Canada Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia PA, USA PM: Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, USA Tate: Tate Gallery, London

Texas: University of Texas, Austin TX, USA V&A: Victoria & Albert Museum, London

YCBA: Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven CT, USA YUAG: Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven CT, USA

References:

BIQ: Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, ed. Morris Eaves and Morton D. Paley, published under the support of Department of English, University of Rochester.

– vii –

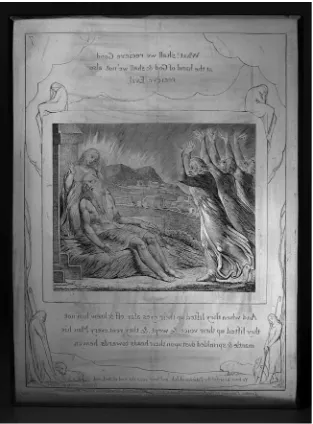

Figure 1: Copper plate verso and the print from its recto on silk, An alle-gorical subject showing eight young girls circling a woman seated among

clouds 56

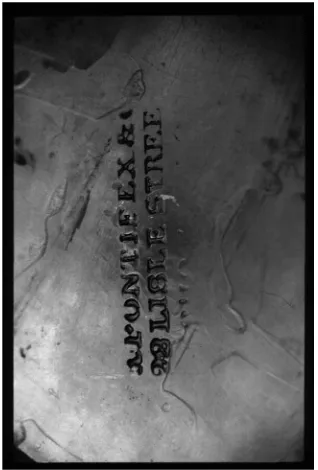

Figure 2: Blake’s Job copper plate, Plate 7, recto 95 Figure 3: Blake Job copper plate, Plate 7, verso 96 Figure 4: Blake’s Job copper plate, Plate 11, recto 101 Figure 5: Blake’s Job copper plate, Plate 16, verso 106 Figure 6: Plate maker’s mark on the copper plate verso of the title page of

Blake’s Job 124

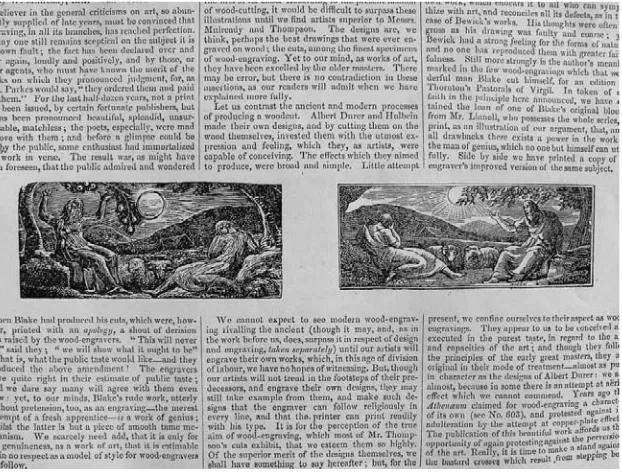

Figure 7: Anonymous woodcut aft er Blake’s design for Th ornton’s Virgil,

no. 2 144

– viii –

Th e research of this book extends from my PhD thesis (Nottingham Trent University, 2005). Th e sequential outcome has been delivered in several con-ferences in the last few years. It started from a joint paper with David Worrall, ‘A Reconsideration of the Execution and Conception: Th e Evidence of Blake’s Job Copperplates,’ presented in the conference ‘Friendly Enemies: Blake and the Enlightenment’ at Essex University (2000). It has become the core of this book. Another paper, ‘Th e Experiments of Colour Printing and Blake Studies,’ pre-sented at the ‘Blake Symposium: Large Colour Prints’ at Tate Britain (2002) has developed into another chapter. ‘Blake’s Copper Plates’ was presented at Tate Britain for ‘William Blake at Work’ (2004), a conference mainly concerned the conservation scientists’ work on Blake. ‘A Virgil Woodcut aft er Blake,’ presented at the ‘Blake at 250’ Conference, York University (2007), was also the outline of a chapter in this book.

from the Bibliographical Society of America, and the UK Printing Historical Society Grant also supported me with further research in this book.

Th anks to Angela Roche and Antony Griffi ths at the Department of Prints & Drawings, British Museum, permission to take photographs of Job copper plates was granted. Kind permissions to photograph for study purposes Blake’s and his contemporaries’ copper plates were given by the Prints & Drawings Room in the Victoria & Albert Museum, the National Art Gallery, Washington DC, and Yale University Art Gallery. Generous help has been given by Craig Hartley at Prints and Drawings of Fitzwilliam Museum, Alan Jutzi at the Ahmanson Room of Huntington Library, and all the staff in the Rare Books Room of British Library, the Beinecke Library, the Rare Books of Bodleian Library, the Special Material of Brotherton Library, Fogg Museum of Art, Houghton Library, the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, the Preston Library at Westminster Archive, St. Bride’s Printing Library, Tate Britain, the National Art Library at V&A, and Yale Centre for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut. Particular warm thanks are to all the friendly staff at the Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University, and the Houghton Library, Harvard University, especially Hope Mayo and Caroline Duroselle-Melish, the curators of Printing and Graphic Arts, for giving me the most delightful experience of examining the uncatalogued (hence unknown to the public) copperplates in the Houghton collection.

My personal thanks are to Professor Christopher Todd for sending me as a stranger a list of his father’s works, Ruthven Todd (1914-1978): A preliminary fi nding-list (2001). Professor Ian Short’s warm friendship came at my most helpless time in UCL. My photographer friend Amingo (Yu-Ming Tsau) took photographs of the Job copper plates for me. Professor Robert Essick gave me the opportunity to see his great Blake collection and information about them. Dr. Steve Clark and Dr. Keri Davies generously gave me numerous and very useful information, support and help in the process of my research. My deep gratefulness is to Professor Edward Larrissy for his support and countless refer-ences for my research applications.

I would also like to pay tribute to Professor Robert N. Essick for his great contributions to Blake studies and generosity as a collector. Much the same, Professor G. E. Bentley Jr.’s monumental works on Blake and his kind encourage-ment and suggestions to my PhD thesis are precious to me.

Finally, my most deep-hearted appreciation is for David Worrall and my par-ents, Ping-Yuan Sung and Ying-Mei Chung, as well as all my family in Taiwan, who give me everlasting support in every way. Th is book is dedicated to them.

– 1 –

ARGUMENT

Th is introductory chapter is intended to announce the scope of this project and to give an indication of the range of issues it will discuss. Th e principal elements of my argument concern the current debate surrounding William Blake’s tech-niques of relief etching and engraving and their context in the survival of the important, yet neglected, archives of his original copper plates in major muse-ums and art galleries.

One of the reasons for the neglect of Blake’s copper plates is that nearly all modern scholars interested in Blake’s printing techniques have focused on his relief etching while ignoring his engraving. Th is is due to a relative devaluation of the technique of engraving which is oft en regarded as an obsolete means of reproduction and which was replaced by other techniques during the nineteenth century. Paradoxically, modern Blake scholarship on engraving has reproduced the very arguments about its low aesthetic valuation which Blake’s Public Address (1810) did so much to refute. With their concentration on etching rather than engraving, notable scholars such as Robert N. Essick, Michael Phillips and Joseph Viscomi may have worked with a contrary emphasis to much of what Blake had to say in the Public Address, his most elaborated discussion of the role of engraving amongst the fi ne arts.1

printing were further elaborated in Phillips’s book, William Blake: Th e Crea-tion of the Songs fr om Manuscript to Illuminated Printing (2000). Publication of Phillips’s book led to a riposte off ered in an article by Essick and Viscomi published in Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, 35:3 (Winter 2002), and in their elaborate online edition of the same essay, ‘An Inquiry into William Blake’s Method of Color Printing’ (http://www.blakequarterly.org).2 Perhaps

some-thing of the heat of the debate is characterized by the title of former Tate curator and Blake editor Martin Butlin’s essay in the same journal, ‘“Is Th is a Private War or Can Anyone Join In?”: A Plea for a Broader Look at Blake’s Color-Printing Techniques’. With hardly any compromise or mediated con-clusion being reached, the argument about process was further complicated by Butlin’s support of Phillips’s theory in his essay ‘Word as Image in William Blake’ published in Romanticism and Millenarianism.3 In the issue of Blake:

An Illustrated Quarterly containing Butlin’s essay, there are also G. E. Bentley and Alexander Gourlay’s reviews of Phillips’s book as a part of the contro-versy. Th is ongoing debate demonstrates the importance of the issue about Blake’s reproductive techniques and printing processes and the profi le of the academic currency amongst some of the most distinguished Blake scholars in recent times. Not least, the public aspects of the Tate exhibition brought the controversy before tens of thousands of visitors, irrespective of whether they perused the accompanying catalogue.4

Th e core issue between Phillips on the one hand, and Essick and Viscomi on the other, is whether Blake used a ‘one-pull’ method or ‘two-pull’ process to print in colour his relief etched copper plates for the illuminated books. In other words, their debate is about printing rather than about etching or engrav-ing although, as I will argue below, the techniques Blake used in producengrav-ing his copper printing plates are the fundamental underlying basis for the production of all the prints produced from them, by whatever means, and by whatever print-ing method. In other words, not only has there been a tendency for engravprint-ing to become subsumed under the category of etching, both of these techniques have become less closely scrutinized than Blake’s printing methods. Th e exhibition of Blake in the Tate Britain from November 2000 to February 2001 aroused much controversy for its central section, ‘Th e Furnace of Lambeth’s Vale: Blake’s Studio and his World,’ the part of the exhibition understood to be organized by the exhibition co-curator, Michael Phillips. As Essick and Viscomi write, ‘in 2000, … printing techniques rose to the forefront of attention among the small band of scholars interested in how Blake made his books as the material foundation for interpretations of what they mean’.5 Despite the words ‘small band of scholars’,

William Blake (1981) is the necessary handbook for all studies of Blake’s art. As an art historian and (now retired) senior curator, Butlin is regarded as authori-tative with his eye very much on artistic techniques and so his entry into the debate is a crucial indicator of the signifi cance of the controversy. Phillips is sim-ilarly a well established bibliographic and historicist scholar of Blake works. Just as Bentley’s Blake Records (1969), Blake Records Supplement (1988), Blake Books (1977) and Blake Books Supplement (1995) are essential for every Blake student, in much the same way, the meticulous historical and material studies of Essick and Viscomi have established highly regarded reputations in the same fi eld, with their work being based on material evidence with wide-ranging and historically empirical scholarship. Moreover, with their exceptional experience in printmak-ing, Essick, Viscomi and Phillips combine their specialities in literary discussion with practical experimentation, producing a kind of reconstructive archaeology of Blake’s printmaking techniques.

Phillips, in the exhibition and in his contribution to its catalogue, William Blake (2000), as well as in his book, Th e Creation of the Songs (2000), advocated a ‘two-pull’ theory without arguing or even mentioning the earlier ‘one-pull’ theory substantially presented by Essick (1980, 1989) and Viscomi (1993). As the latter two writers point out, ‘the two-pull theory is described [by Phil-lips] in a straightforward manner that implies it is a generally accepted fact.’6

Indeed, there was signifi cant omission of the relevance of the arguments of Essick and Viscomi in the Blake exhibition at the Tate Britain. Visitors to the exhibition and purchasers of the catalogue were not made aware of the compet-ing interpretation of technique put forward in Essick and Viscomi’s work. Th e ‘one-pull’ theory represented by Essick and Viscomi assumes that Blake printed his illuminated books by passing the inked text and coloured image through the rolling press simultaneously, in one pass. Both Essick and Viscomi carried out their experiments of relief etching in an attempt at reconstructing Blake’s print-ing methods, and argued against their precursor Ruthven Todd’s theory (1948) that Blake used transfer techniques (Essick 1980, ch. 9; Viscomi 1993, ch. 1). Viscomi’s Blake and the Idea of the Book (1993) received great attention from Blake scholars during the 1990s, and is still regarded as a seminal work on Blake’s techniques. Indeed, there can be no doubting the contribution to Blake stud-ies made by Essick and Viscomi. Th eir work is founded on a practical emphasis on empirical evidence drawn from reconstructive printmaking techniques allied to a profound knowledge of the range of Blake’s works. However, neither the section ‘Blake’s Illuminated Printing’, written by Phillips in the Tate Britain exhibition catalogue, nor his British Library monograph study, Th e Creation of the Songs (2000), refers to Essick’s or Viscomi’s theories. Not only does Phillips display a multistage process of relief etching on the copper plate,7 but he also

copper plate through the press more than once to print text and image sepa-rately using an accurate process of registration.8 Again, the public status aff orded

by the Tate Britain exhibition, accompanied by the eminence in bibliographic study implied by the British Library imprint makes the exclusion of a consider-able body of alternative research endeavour all the more signifi cant. Not least, although it may prove to be only of tangential relevance to the discussion of printmaking, the Blake Tate Britain exhibition – and its catalogue – is bound to become a standard reference point for establishing matters of both provenance and economic value. It is safe to predict that, as this is one of their major modus operandi in estimating the market, the Tate catalogue will in future be frequently used by dealers, auctioneers and the public and private collectors whom they serve.

a printmaker known through his work for the Th omas Bewick Birthplace Trust established in 1982.

In Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly 35:3 (2002), Essick and Viscomi illus-trated new experiments arguing against Phillips and defending their earlier theories in the essay, ‘An Inquiry into William Blake’s Method of Color Print-ing’. Th eir experiments were to print from electrotypes using both one-pull and two-pull methods to show their diff erences, also using the aid of devices such as magnifi cation and Adobe PhotoShop computer soft ware to reveal colours in detail on Blake’s prints. Th e motive behind these detailed experiments was to argue against every point of Phillips’s theory and to insist that Blake’s printing method is ‘one-pull’ and no other (except in the possible case of ‘Nurses Song’ in the Songs of Experience Copy E, Huntington). Th ese scientifi c methods and empirical experiments present strong evidence to support Essick and Viscomi’s earlier arguments.

Taking together Phillips’s ‘Correction’ essay, Butlin’s article supporting Phil-lips, Essick and Viscomi’s co-authored response, and mixing these with Bentley’s and Gourlay’s reviews, one can say that no other publication marks the peak of the controversy about Blake’s printing methods more than this single issue of Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly, 36:2 (Winter 2002). Of course there were also less partisan reviews of the Tate Britain Blake exhibition and its catalogue by Morton Paley (2002) and Jason Whittaker (2002), which followed in the wake of these controversies. In other words, at least eight of the most eminent contemporary Blake scholars were engaged in an increasingly heated debate, not about the interpretation of imagery or poetry but quite simply about techni-cal process. Indeed, aft er 2002 the controversy arguably intensifi ed still further with Martin Butlin’s online response ‘William Blake, S. W. Hayter and Color Printing’ (2003), Essick and Viscomi’s replies on the same website10 as well as

Phillips’s most recent essay on Blake’s printing of the sole surviving America: A Prophecy (1793) plate fragment.

sur-prising. While their existence has sometimes been noted in passing, my study is the fi rst to analyze them in detail and to present the evidence they aff ord. On the face of it, this may seem an odd absence in Blake studies which, as has been shown, is a research fi eld demonstrably amongst the most vigorously contested in Romantic studies. Similarly, contemporary critical investment in studying Blake’s prints made by relief-etching, the basis of the illuminated books of poetry, has been accomplished at the cost of neglecting his engraving, the technique which required greater professional skill and dexterity than etching. Not least, as Blake’s extant printing plates are physically robust and represent the artist’s last personal contact with the source of his images – very much an exemplar of a Romantic ide-ology of the artist – the neglect of the printing plates is all the more surprising.

It is only very recently that Blake scholars have begun to notice the impor-tance of his extant engraved copper plates. Following some time aft er my fi rst paper on this subject, ‘A Reconsideration of the Execution and Conception: Th e Evidence of Blake’s Job Copper Plates,’ presented at the ‘Friendly Enemies: Blake and the Enlightenment’ conference at Essex University (August 2000), there has been increasing attention paid to Blake’s copper plates. Publications in the public domain include Michael Phillips’s ‘Th e Printing of Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job,’ Print Quarterly, 12:2 (2005), and G. E. Bentley’s ‘Blake’s Heavy Metal: Th e History, Weight, Uses, Cost, and Makers of His Copper Plates,’ Uni-versity of Toronto Quarterly, 76: 2 (Spring 2007).11

At this point it may be helpful to summarize the extent of the known archive of Blake copper plates. Th ere are thirty-nine known and traceable printing cop-per plates by Blake in existence, including thirty-two exclusively made by Blake and seven cooperative plates made by Blake and others. Th e thirty-two copper plates solely executed by Blake include a fragment of one etched plate, the Amer-ica cancelled plate a (NGA Washington DC) and thirty-one engraved plates. Th ese are the single plates of the Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims (Yale Univer-sity Art Gallery), Th e Beggar’s Opera aft er Hogarth (Houghton, Harvard), seven plates for the Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy (NGA Washington DC) and the twenty-two Illustrations of the Book of Job plates (BMPD) (See Figure 1). In addition, there are six plates for Gough’s Sepulchral Monuments (Bodley, Oxford) and the single plate Christ Trampling on Satan (Pierpont Morgan, New York), partially engraved by Blake. Among them, only the etched plate America a has received scholarly attention before 2000. Perhaps because of the critical and cultural capital invested within university English Literature departments, only the single surviving fragment of one of Blake’s illuminated books of poetry – a few centimetres across – has been thoroughly analysed.

reconstructive printing) over a fi ft y-year period by W. E. Moss, Ruthven Todd, William Hayter, Robert Essick, Joseph Viscomi and Michael Phillips.12 Despite

all of these experiments, this piece of copper plate has not been investigated for its own sake as also suggesting a body of possible evidence about Blake’s other techniques, but simply for furthering the project of the reconstructive recovery of his method of relief etching. For example, the deep gouge on the recto, and the engraving on its verso (possibly by Th omas Butts Jr) has not been properly explained or examined. In Chapter 2, I will show that these marks are those of the corrective technique of repoussage, a practice found in abundance on the Job copper plates (see Figure 2) Equally remarkably, none of the other thirty-one engraved plates by Blake has received the equivalent attention given to the single surviving etched plate fragment, with the possible exception of where, as with Blake’s plate aft er Hogarth located at the Houghton, modern restrikes have been taken (and have now found their way onto the print dealer market). Moreover, apart from the recently resurfaced Christ Trampling on Satan,13 there is an even

more ready scholarly dismissal of the possible signifi cance of six further copper plates, among four hundred for Richard Gough’s Sepulchral Monuments (1786), which are only conjecturally attributed to Blake. Th ey have been left neglected in the storerooms of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and for many years ignored by most Blake scholars.

Although there was a short revival of interest in the technique in the late nine-teenth century, engraving has lost its golden age forever and has been abandoned by most modern printmakers. By contrast, the less exacting medium of etching has won many modern artists’ favour and has been regarded as a free means of innovative creation. Th e rise of etching, and the comparable fall of interest in engraving, has infl uenced Blake studies in a subtle way, one not always made explicit to Blake students.

It has also been less well understood that the group of twentieth-century scholars interested in Blake’s printmaking techniques themselves had a number of connections with modern artistic circles, either by directly cooperating with artists or practising printmaking themselves. Graham Robertson, who discusses Blake’s colour printing methods in his edition of Gilchrist’s Life of William Blake (1907), was an artist himself as well as being a principal benefactor of the Tate Gallery, London, where he bequeathed most of its important Blake collection, including the best known version of the iconic print, Newton (1795).14

(1893–1983), two eminent Surrealist artists. Essick, Viscomi and Phillips all have experience in practical printmaking and experimenting on Blake’s making of relief etching and printing. Th e latter two refer directly to their experiences as artistic printmakers in their books, Blake and the Idea of the Book (1993) and Th e Creation of the Songs (2000). Of course, the artistic background of these schol-ars has substantially assisted their study of Blake’s techniques, helping validate their carefully formulated – if contrary – interpretations. However, they have also been less obviously – but nevertheless profoundly – infl uenced by modern artistic judgements about comparative value within their professional fi elds as university tutors of English literature. Th e focus on Blake’s relief etching to the neglect of his engraved copper plates is a signifi cant consequence of an attach-ment to the processes which resulted in the illuminated books becoming works crucial to the position of Blake’s poetry within the English literary canon.

Most of the scholars interested in Blake’s techniques are also, even if to vary-ing degrees, collectors of his original works. Graham Robertson, W. E. Moss, Ruthven Todd, Geoff rey Keynes, Robert Essick and Michael Phillips were or are all collectors of Blake’s works. Even one of the least well-known collectors from this group, Ruthven Todd, owned a receipt signed by Blake to Th omas Butts, 9 September 1806,15Illustrations of the Book of Job (1826) Plates 20 and 21,16

and fi ve of Blake’s separate plates: Th e Fall of Rosamond (1783),17John Caspar

Lavater (1787),18Christ Trampling on Satan (c. 1806–8),19Th e Man Sweeping

the Interpreter’s Parlour (c. 1822)20 and all four states of Wilson Lowry (1824–

5).21 Although implying himself to be fi nancially precarious in a wartime letter

to Graham Robertson, Todd still managed to acquire this small but important Blake collection.22 Between them, Robertson, Moss, Keynes and Essick have also

owned, sold-on or bequeathed a number of crucial Blake pictures, books and artefacts. Recently, Michael Phillips – not without controversy on account of their unproven authenticity – exhibited three items from his own collection in the Blake Tate exhibition (2000), which he claimed contain Blake’s authenticated drawing or writing.23 Considering that he entitled one of his most celebrated and

striking illuminated books Milton: A Poem (1804–20), one of these items, an 1732 Richard Bentley edition of Milton’s Paradise Lost alleged to be copiously annotated with marginalia by Blake, stands to be an undoubtedly signifi cant fi nd if authenticated. However, like the Phillips-owned so-called ‘Sophocles notebook,’ the attribution to Blake of the Paradise Lost annotations has been critically challenged, notwithstanding their exhibition at both Tate Britain and, subsequently, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.24 Further evidence,

require some measure of caution when interpreting the subsequent hermeneutic of Blake’s work which results.

Th e slightly parochial nature of the academic contestation – even if played out in the exhibition halls of the major international galleries – is a reminder that the interpretative high ground in the judgement of commercial and artistic value involves an untidy melee of public benefactors, private collectors, university aca-demics and museum curators together with, not least, the exclusively recondite world of dealers and auction houses, a profession not unacquainted with crimi-nal convictions in recent years (for example, in the case of Sotheby’s chairman Alfred Taubman convicted of illegal price fi xing, see Th e Times, 23 April 2002). Th e interest and demand for Blake’s relief etchings raises their prices on the mar-ketplace, therefore encouraging a hierarchical judgement of his art. Although there is an understandable reluctance to admit the hierarchical view of artistic technique, modern Blake scholars appear to always bear in mind that engraving as a reproductive technique is signifi cantly less valuable than etching, which is seen as a better method of revealing an artist’s creativity in printmaking. In other words, by processes of either commission or omission, modern Blake scholars have been complicit in under-privileging Blake’s technique as an engraver.

In fact, the decline in esteem of engraving started in Blake’s lifetime. Th e engravers’ dilemma was whether to consider themselves commercial or high artists. Many scholars have discussed the exclusion of engravers from the Royal Academy of Arts.25 As D. W. Dörrbecker (1994) points out, Robert Strange’s

Inquiry into the Rise and Establishment of the Royal Academy of Arts (1775) and John Landseer’s Lectures on the art of Engraving (1807) represent the engrav-er’s protests against this discrimination. Th e notion of originality grew stronger through the nineteenth century26 and, by the twentieth century, innovation

and originality became the core for the judgement of artistic value. Modern Blake studies refl ect this evolution of the judgement of art. Certainly, Blake’s Job engravings were already highly admired by his contemporaries, even during the lengthy process of their execution.27 Th e nineteenth-century art critic John

Ruskin regarded them as Blake’s best work,28 but the original copper plates have

been under-examined in modern times. By contrast, because Blake’s illuminated books are today held in higher critical esteem, research into processes of relief etching and printing from relief etched plates has been pursued with the most noticeable vigour. To complete the paradox, etching is a technique which (then as now) is less skilful than engraving, arguably less a measure of Blake’s command of his craft technique.

Th e term ‘original print’, distinguished from reproductive engraving, is attributed in the late nineteenth century to works of printmakers such as Dürer to defi ne the prints made from the engraver’s own design.29 Blake’s Job falls into

the traditional technique of engraving to which it applies is somewhat deval-ued and so Blake’s Job has come to be regarded by modern scholars, perhaps dismissively, as a ‘middle ground’30 between reproductive engraving and original

relief etching. Th is hierarchical judgement of artistic value, although perfectly understandable once it has been historicized, has caused an unjustifi ed neglect of Blake’s engraved copper plates.

Among the extant copper plates of Blake, the twenty-two Job plates in the British Museum Prints and Drawings (hereaft er BMPD) should be considered the most important material for investigation. Th is is not only because of the substantial number of the copper plates, but also because the Job plates are the most complete set that was made late in Blake’s life, they have the added scholarly attraction of having been the subject of well-documented records kept by the Linnell family. While other completed plates might have involved other hands in engraving or restoration, the Job plates are the best evidence of Blake’s technique untouched by others, thanks to John Linnell’s retention of them prior to their safe own-ership by the British Museum from 1918. Of the others, the Dante plates are unfi nished; the six Gough plates were executed during Blake’s apprenticeship cooperatively in Basire’s workshop and so are probably not entirely his work; Christ Trampling on Satan was engraved by Th omas Butts Jr with the assistance of Blake; the Hogarth plate was repaired by later commercial printers.31 A later

impression of this last plate, in Th e Works of William Hogarth, fr om the Origi-nal Plates Restored by James Heath was published in 1822 by Baldwin, Cradock and Joy. Essick suggests that James Heath probably executed some work on the fourth state (1822).32 Th e Hogarth plate was also ‘thoroughly repaired by

Rat-cliff , of Birmingham’.33 In other words, the current state of the Hogarth copper

plate does not contain Blake’s exclusive handiwork. Th e large plate of Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims is perhaps the second most important copper plate worth taking into account as being representative of Blake’s technique and skill, except that its solitary status cannot compare with the twenty-two Job plates. However, despite the importance of the Job designs recognized by Linnell, the Job copper plates themselves have been paid little attention aft er they were deposited in the BMPD, and it is surprisingly easy to document this scholarly neglect.

In all the past studies of Blake except the two recent essays by Phillips (2005) and Bentley (2007) mentioned earlier, the Job copper plates have only been men-tioned by a few scholars in very brief accounts. Keynes mentions the existence of Blake’s copper plates in a short article in his Blake Studies but adds no description or other examination.34 Bentley noticed the two reused copper plates, Plates 14

was only two years old. Bo Lindberg’s William Blake’s Illustrations to the Book of Job (1973), which is a combination of material, historical studies and icono-graphic interpretations, and usually thought to be the most exhaustive study on the subject, mentions and provides the British Museum location data for the plates but otherwise completely ignores them. However, Lindberg’s chapter on the engraving technique is not based on an examination of the Job copper plates themselves although he was obviously aware of their existence. Aft er Lindberg’s book, William Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job, edited by David Bindman (London: William Blake Trust, 1987), is the most recent and ambitious work intended to cover all the materials available for the study on Blake’s Job engrav-ings. However, it includes only a small section, written by Essick, on the copper plates which contains information (which can now be updated in the light of the evidence presented here) concerning ‘chisel marks’ on their backs, supposing that these marks were made during planishing, the process of hammering metal plates to make them fl at and hard before engraving.36 Lindberg’s interpretations

were made without the foundation of close material study and demonstrate the extent of the neglect of these copper plates. Th is amounts to the absence from scrutiny of the most basic material in these studies, namely the plates themselves, and it very largely accounts for the consequent tradition of misinterpretation.

Th e neglect of Blake’s engraved copper plates has also resulted from the extensive elaboration of an expressly literary theory, the notion of the unifi cation of inven-tion or concepinven-tion and execuinven-tion, largely pursued by Essick and Viscomi. Th e theory, developed from the ‘one-pull’ theory of printing, is sought specifi cally to correspond to Blake’s claims for divine inspiration in his creative processes. Essick and Viscomi imply that Blake realized his theory of unifying invention and execution as a result of his practice of printmaking. Th e key statements for our understanding of how their argument emerged come from Blake’s own statements that ‘Invention depends Altogether upon Execution or Organiza-tion’ (E 637) in his annotations to Reynolds’s Discourses, and his antipathy to ‘the pretended Philosophy which teaches that Execution is the power of One & Invention of Another’ (E 699). Th e unity of invention and execution, hand and mind working as one, implies a ‘spontaneous’ and ‘immediate’ process of creation.37 Th is takes literally Blake’s own description in a letter to Th omas Butts

Blake’s unique method of relief etching provided a medium for his most radical experiments in the interweaving of graphic conception and execution within a seam-less process of production. Rather than transferring a design prepared in a diff erent medium to the copper, the relief etcher can compose directly on the plate.38

Viscomi says, ‘illuminated printing represents undivided labor, unifi ed inven-tion and execuinven-tion, and unconveninven-tional producinven-tion’,39 and claims that Blake’s

‘working without models’ in relief etching is ‘a composing process that enabled Blake to put his thoughts down on copper immediately’.40

Essick and Viscomi endeavour to prove that Blake designed and drew directly onto the copper plate without transferring from models. Directly designing on copper plate is like drawing and painting on canvas, thus unifying invention and execution.41 For Essick and Viscomi, it is in the same way that Blake’s supposed

one-pull procedure of printing unifi es invention and execution by colouring and printing in one go without separating this stage of the process into mechanical divisions.

However, engraving does not fi t into this method or the theory which is at the core of what Essick and Viscomi argue. Th e reason why engraving does not fi t this theory is that engraving nearly always requires models and transfer techniques and, in any case, the ‘push’ and ‘pull’ process of moving the engrav-er’s burin is quite contrary to the fl uent sketching with the etching needle, or writing with a brush dipped in acid-proof liquid. In an even greater distinction between the production processes of the illuminated books, even though they used Blake’s original design, the Job engravings were printed by another hand, the professional copper plate printers Lahee and Dixon. Th e division of invention and execution, as far as the printing of the Job plates is concerned, could hardly be greater. In other words, the paradigm of etching employed by Essick and Vis-comi, while it may hold true for the illuminated books, cannot be followed in the engraved Illustrations of the Book of Job, a work printed by commercial copper plate printers.

As will be discussed in Chapter 3, a major part of this study, close examina-tion on Blake’s copper plates, especially on the Job plates, reveals for the fi rst time that the technique of repoussage was extensively used by Blake on the versos of the copper plates to mend wrongly engraved lines. Th is is a very signifi cant fi nding. As described in handbooks of printmaking, the technique of repoussage is used to correct serious mistakes occurring on line engraved copper plates by scraping and burnishing the lines and hammering up the area from the back of the plate to make it into an even surface for further re-engraving. Although men-tioned by a few scholars, these hammer marks have never been taken seriously, or properly understood in their functions.

dis-coveries outlined in this book. Th e examination of Blake’s copper plates plays a central role in this study to draw attention to this important but much-ignored material evidence. With the aid of simple measuring tools, one can observe that the hammer marks on the verso of the copper plate correspond exactly to the engraved lines and fi gures on the recto of the plate. Th ey also match the changes made by Blake noticed by Robert Essick on early print proofs to the fi nal state. Th ese prove that the hammer marks are neither random nor made by anyone other than Blake himself. Th ey are indeed the traces of the technique of repous-sage, the materially indelible process of repeatedly correcting and modifying original conceptions.

As with most scholars of engraved prints, Essick’s method is to compare dif-ferent proof states and to trace their development, systematically, from the fi rst working proof to the fi nal state.42 In this way, he has observed many important

changes in Blake’s Job and other engravings. Th is methodology, which is used by most scholars of prints, directs us to the prints rather than the copper plates from which the prints were produced. However, the examination of copper plate and repoussage has revealed another important source for our understanding of Blake’s techniques as a craft sman.

In addition, this book will show that repoussage is not only found on the versos of the Job copper plates, but also on most of Blake’s other extant copper plates. Chapter 3 will discuss the discovery of repoussage on the copper plate of Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims, Th e Beggar’s Opera aft er Hogarth, the plates for the Illustrations to Dante’s Divine Comedy, and even the early Gough plates. Th ese discoveries tell us that Blake made mistakes in engraving throughout his career, right from the period of his apprenticeship work on the Gough plates to the end of his life when he worked on the Dante plates. Th ese not only include commercial plates, such as the Gough plates and the Hogarth plate, but also the plates made to his own designs, such as Chaucers Canterbury Pilgrims, Job and Dante.

Keynes mentions the technique of correction on copper plates by knocking the copper up from the back in his essay ‘On Editing Blake’,43 but only in

work-ing from an assumption that Blake might have used it on Jerusalem, Plate 37. Viscomi recognizes the existence of the technique of repoussage,44 but does not

identify its actual use on Blake’s extant copper plates. A photograph of repoussage on a copper plate is shown by Morris Eaves45 to illustrate its function of

although Eaves discusses Sharp’s plate in the context of the engraving trade in the late eighteenth century in his monograph Th e Counter-Arts Conspiracy: Art and Industry in the Age of Blake (1992), he made no examination of hammer marks or copper plates on Blake’s own work. It is clear that changing the images on cop-per plates requires the technique of repoussage. In Eaves’s example, the technique is not for correction but for revision. Blake’s designs of Job engraving, however, have no intention of revising the central images because they strongly resemble his early watercolours for Job made for Butts and Linnell. Th e repoussage on the versos of Job copper plates, therefore, bespeaks correction for detailed mistakes, as well as a hesitation in the skill and fl uidity of his technique.

It reminds us of a very early commentary on Blake’s Job engravings only two months aft er their publication, and the fi rst and only printed reference in Blake’s lifetime, in a weekly journal Th e Star Chamber, 4 (Wednesday 3 May 1826), pos-sibly by the later prime minister Benjamin Disraeli (1804–81).46 Remarkably,

Disraeli not only wrongly – but revealingly – identifi es the Job engravings as ‘etching’, he also comments on their perceived lack of ‘skilful execution’.

Mr. William Blake, whose illustrations in outline of Young, Gray, and other poets have been long before the public, has completed his designs for the Book of Job. Some of the etchings are full of that remarkable wildness and singularity of concep-tion, for which Blake is so well known. Th e embodying of the plagues infl icted on Job by the Almighty, the personifi cation of a Night-mare, and the fi gures of the creation, are wonderful, although we do not think them equal either in point of originality or skilful execution to some of the earlier productions of this extraordinary artist.47 Th is verdict corroborates Blake’s earlier perception in Th e Public Address (1810) that:

To what is it that Gentlemen of the fi rst Rank both in Genius & Fortune have sub-scribed their Names [–] To My Inventions. the Executive part they never disputed the Lavish praise I have received from all Quarters for Invention & Drawings has Gener-ally been accompanied by this he can conceive but he cannot Execute. (E 582)

Modern scholars, in defence of Blake’s art, tend to dismiss this kind of criticism. However, to place Blake in the context of his time and print culture, we need to reconsider Blake’s artistic skills carefully.

to encompass the very diff erent technique of engraving, as if the spontaneity of etching was also a characteristic of engraving. Rather, the Job plates are a long term labour involving careful processes of composition, modifi cation, resizing, reorganization, and trial and error. On these plates, Blake certainly did not unify his invention and execution. If Blake did succeed in the unity of invention and execution in his writing and relief etching, he did not achieve the same ideal in engraving, either for commercial plates or for his own designs.

While tracing the background of the theory of the unifi cation of invention and execution, I found a long history of argument in Blake studies, which reveals an unexpected source from the Surrealism movement of the 1930s and 40s. Th e ‘one-pull’ theory of Essick and Viscomi follows the experiments in 1947 by Ruthven Todd, who was inspired by Graham Robertson’s experiments of 1906 and W. E. Moss’s experiments around the same time. Against Frederick Tatham’s account about Blake’s process of printing in Rossetti’s ‘Supplementary’ chapter to Gilchrist’s Life of William Blake, Robertson held a ‘two-pull’ theory, think-ing that Blake printed his Large Colour Prints (c. 1795–1805) in a multistage procedure. Todd held the opposite view, the ‘one-pull’ theory, echoing Tatham but (like Essick and Viscomi) mainly concerned with Blake’s relief etching of the illuminated books rather than the Large Colour Prints. Th is ‘one-pull’ theory, in turn, infl uenced Essick and Viscomi, although the latter two are against Todd’s transfer theory. What has not been considered thoroughly is that Todd in his experiments on Blake’s printing of relief etching cooperated with two important Surrealist artists, William Stanley Hayter and Joan Miró. Blake scholars have never paid much attention to the close relationship between Todd and Surre-alist artists of the 1930s and 40s, and its infl uence and association with Blake studies. Th e history and contexts of these competing early and mid-twentieth century theories about printmaking, which will be outlined in Chapter 1, adds an extra dimension of complexity to the current debate. Th is Chapter traces the inheritance of early to mid-twentieth-century ideas in order to understand the background of the argument about Blake’s methods, which are a central concern in current Blake studies. It is not my attempt, however, to join in the argument about Blake’s printing methods, but to highlight the missing element in the Blake controversy: the neglect of Blake’s engraved copper plates, and to fi nd out the reasons for such neglect.

engravers in major collections, which have obviously also been ignored for a long time. Th ese collections include the Bodleian Library Oxford, British Museum, Houghton Library (Harvard), Huntington Library (CA USA), Lewis Walpole Library (Yale), Museum of Fine Arts Boston, National Gallery of Art Washing-ton DC, Pierpont Morgan Library (New York), Tate Britain, and the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Th e aim of this book, therefore, is a reinforcement of material and histori-cal studies. In the Blake conference during the Tate Exhibition of 2000, ‘Blake, Nation and Empire’, organized by David Worrall and Steve Clark on 8 and 9 December 2000, there were concerns expressed from the fl oor as to whether Blake studies had become too historical and should aim to go back to Frye’s interpretative methodology. In a recent study, Sheila Spector in ‘Glorious Incom-prehensible’: Th e development of Blake’s Kabbalistic Language (2001) says ‘having re-introduced consciousness into the study of Blake, scholars have begun to explore nonmaterial aspects of the emotive and rhetorical approaches to Blake’ (p. 27). In the ‘Blake at 250’ Conference at York in 2007, there was also a heated debate from the fl oor between historical and hermeneutic approaches to Blake studies. Th e emphasis on nonmaterial aspects seems to reject material studies and suggest that there is an emerging view that the material studies of Blake have been over-stressed. Th is book will demonstrate the continued potency of material studies, whose importance as a foundation for interpretation of Blake’s works has for years been established by scholars, such as Geoff rey Keynes, David Erdman, G. E. Bentley, Jr., Robert Essick, Jon Mee and David Worrall. Close examination of fi rsthand material is essential before any interpretation can be made. At the very least, my book may serve as a record of an eyewitness, a poten-tially valuable contribution in a world where material artefacts, despite their physicality, do not escape destruction.

Th e relative impermanence of Blakean artefacts has been highlighted in Robert Rix’s PhD thesis, Bibles of Hell: William Blake and the Discourses of Radicalism,48 which discusses the apparent deterioration of a pencil sketch

drawn by Blake on his copy of Francis Bacon’s Essays Moral, Economical, and Political (1798). Blake’s annotated copy of Bacon in the Cambridge University Library shows a drawing on p. 55, described by Keynes and by Erdman,49 ‘Th e

devils arse [with chain of excrement ending in] A King’ (E 624). However, Rix recently found that the original sketch has been erased at the top, where the words ‘Th e devils arse’ and the buttocks were originally evident.50 It is recovered

by Keynes’s imitation in pen of Blake’s annotations on another copy of the same book.51 Th e erasure of the image is not mentioned by Keynes or Erdman, but

only later noticed by Bentley.52 Although this erasure has been a mystery, and no

eyewit-ness account, at the fi rsthand, artefacts rather than dependence on secondhand records.

With the same purpose, the exposition of copper plates in this book also serves as a record, or eyewitness, of important original materials by Blake’s hand which have not hitherto been collated. Should there be any deterioration of the material in the future, this record may at least preserve information for future studies.

In art history, a recent scholarly tendency has similarly emphasized material studies and conservation. Th e exhibition of Blake’s contemporary, watercolour-ist Th omas Girtin (1775–1802), at the Tate Britain from 4 July to 29 September 2002, showed concern for his working methods in the studio as well as from nature. In the exhibition and its catalogue, Th omas Girtin: Th e Art of Watercol-our,53 the study of materials and techniques, along with the display of unfi nished

works in progress, reveal artists’ working practice, the foundation of their ideas and achievement being equally important to the study of their lives and histori-cal contexts. In addition, the unavoidable degradation of artworks shows the importance and urgency of conservation and how this exhibition and its mate-rial studies serve as an eyewitness at the present time. In this respect, the very physical permanence of Blake’s copper plates makes it even more extraordinary that they have been neglected.

As the study of Blake reaches this scientifi c level, conservation of Blake’s works becomes essential. Th e need for the conservation of Blake’s work exists not only because of the quick deterioration of paper and the pigments on his temperas and colour prints, but it also gives an opportunity for the scientifi c analysis of the materials, which helps us to understand how they achieve their eff ect as works. Th e analysis of Blake’s media, for example, the binder and pig-ments Blake used for colour printing, becomes important for understanding of Blake’s techniques, the eff ect he achieved and the reasons why his choice was so diff erent from his contemporaries. For example, Michael Phillips cites the chemical studies of Robert Essick, Anne Maheux, Joyce Townsend and Sarah L. Vallance on Blake’s media to explain how he made the mottled eff ect on colour prints.54 Essick and Viscomi also pay much attention to Blake’s printing media.55

Th ese studies further indicate the signifi cance of materials and the continuing demand for investigation. However, the paradox continues: despite the very fra-gility of paint and paper, Blake’s prints have received extensive consideration and examination. Th e extant copper plates, the most materially stable artefacts to have survived from Blake’s lifetime, have been neglected.

medium from engraving, the working method of the Large Colour Prints also shows some inconsistency, and breaks the ideal of unifi cation of invention and execution, similar to the Job engravings. Th e printing of these works does not seem to be done totally in one-pull, nor with any evidence of two-pull with reg-istration, but rather a middle-way method. Accordingly, more study of Blake’s materials is urgently needed. Most likely Blake did not insist using only one method but chose whatever was convenient to him.

– 19 –

CONCEPTION AND EXECUTION

Amongst studies of Blake’s etching and engraving techniques on copper, there is no doubt that the most important in recent times are those put forward by Robert Essick and Joseph Viscomi. Both of them have dominated discussion of Blake’s printmaking techniques, especially the technique of relief etching. Essick’s William Blake, Printmaker (1980) brings out the artisan’s life of Blake, his profession, his medium and technique. Th roughout William Blake, Print-maker, we can see for the fi rst time how Blake worked on copper plates.1 Essick

successfully gives us a clear view of the life Blake lived as a professional engraver and printmaker under the general public taste of the eighteenth century, and his struggle to move from being an ordinary reproductive printmaker to being an original artist. Following Essick’s practical and detailed research, Viscomi’s infl uential Blake and the Idea of the Book has similarly become one of the most indispensable books for Blake studies. Working apparently increasingly interde-pendently, at least aft er William Blake, Printmaker, Essick and Viscomi have had intellectual collaboration and shared similar ideas. Th eir argument for the unity of invention (or conception) and execution has also become widely known,2 and

cannot be ignored by anyone studying Blake’s copper plates and techniques. Th e theory of the unity of invention and execution is subtly presented in Essick but pushed to the extreme by Viscomi. Th is is most clearly expressed in Blake and the Idea of the Book (1993):

tech-nically possible for Blake to write, as Blake told Butts, ‘twelve or sometimes twenty or thirty lines at a time without Premeditation & even against [his] Will’ (E 729). Because illuminated printing and oral-formulaic poetry are both autographic, they technically could have occurred concurrently.3

It is clear throughout his book that Visomi’s assumption is that illuminated printing represents undivided labour, unifi ed invention and execution, and unconventional production.4 Yet the assumption is extended to the whole of

Blake’s printmaking so that his readers hardly notice that it only covers the relief etched illuminated books and not his engravings, which were Blake’s main career output.

Similarly, Essick says in his William Blake, Printmaker that Blake’s graphic techniques (for relief etching in particular) are themselves claimed to possess intrinsic meaning as ‘activities of mind’.5 In Essick’s words, ‘when Blake

exag-gerates these commercial techniques and raises them so far above the threshold of vision that they replace representational forms and become that which is represented’.6 In short, ‘graphic method becomes part of verbal message’.7 With

‘method’ becoming ‘message’, Essick’s eff ort of building ‘conception’ into Blake’s ‘execution’ is clearly seen. His discussion of technique (the execution) is working towards the theory that Blake as an artist chose the technique with his mind, not as an artisan controlled by the mechanical. We should note, however, the word ‘execution’ here is restricted to relief etching, a technique which Essick and Viscomi noticeably privilege.

Essick’s tendency to emphasize relief etching leads to the implication that Blake used it as his most successful way of combining invention and execu-tion. Aft er his return from Felpham to London in 1803, Essick claims Blake ‘return[ed] to his earlier graphic innovations as a means for communicating his renewed vision’.8 By this, Essick means the relief etching of both text and design.

In the letter to Th omas Butts of 10 January 1803, Blake wrote he had resumed his ‘primitive & original ways of Execution in both painting & engraving’ (E 724). Essick is certain that ‘by this Blake must have meant relief etching’.9 Essick’s

theory of Blake’s ‘unity of invention and execution’ is more fully presented in William Blake and the Language of Adam. Although William Blake and the Language of Adam is not particularly concerned with Blake’s craft techniques, it is clear that the preconditions for his interpretation of Blake were established and laid out in the primary work done for William Blake, Printmaker. In chapter 4, ‘Language and Modes of Production’, Essick argues that, for Blake, there is ‘no distinction between the source of conception and the medium of its exe-cution: the medium is the origin’.10 Th is is taking the cue from Blake’s words

Another’ (E 699). Although William Blake and the Language of Adam does not refer much to Blake’s copper plates or practical techniques, it is based on the practical ground of his earlier research, and its infl uence has been continuing for more than a decade. In Essick’s theory, the ‘spontaneous’ and the ‘immedi-ate’ played a major role in Blake’s inspiration of poetry as well as his pictorial production.11

However, the theory about Blake’s execution and conception was not Essick and Viscomi’s invention. It has a long history back in the early Blake studies and an artistic and literary background in the early twentieth century. Th is chapter will show how the Essick/Viscomi thesis of the unity of invention and execution in Blake’s relief etching is actually a later incarnation of early twentieth-cen-tury idealizations of automatic writing developed by 1930s and 40s Surrealists including, most notably, the Blake scholar Ruthven Todd who not only car-ried out reconstructive experiments (as Essick and Viscomi acknowledge) but who had close links with major Surrealist printmakers who were enthusiastic about the possibilities of automatic writing. Th e certainty with which Viscomi both assents to, and validates, Essick’s preliminary work is notable. As quoted before, Viscomi wrote in Blake and the Idea of the Book that ‘Essick shows in William Blake and the Language of Adam why Blake’s metaphor of “dictation” was not mere topos … Blake’s aesthetic of uniting invention and execution made it possible to write, as Blake told Butts … “without Premeditation” … Because illuminated poetry and oral-formulaic poetry are both autographic, they tech-nically could have occurred concurrently’.12 Ruthven Todd’s Surrealist friends

would have heartily agreed. While Joan Miró, William Hayter and, of course, Ruthven Todd actually experimented directly in reconstructing Blake’s methods of relief etching, Blake was already a much-celebrated fi gure amongst Surrealists fascinated by what they called, ultimately derived from their understanding of Sigmund Freud, ‘automatic writing’. Th e Essick/Viscomi thesis is not without its own, unacknowledged, genealogy in Surrealist practices.

as a major collector of Blake’s works as well as on account of his own studies of Blake. Th e correspondence between Moss and Todd reveals the exchange of ideas and sharing of interests. One crucial item originally in Moss’s collec-tion is the unique fragment of the etched copper plate America plate a (NGA), which came to Todd’s attention and inspired his experiments in 1947. Todd was obviously animated by Moss’s experiments in printing from this etched plate, as well as Graham Robertson’s experiments with colour printing from millboard. Th is chapter will show the history and relationship of these early Blake schol-ars and how Todd played a central role as an infl uential fi gure. Th e chapter will also throw new light on the neglected fi gure of Moss whose crucial role in Blake studies still needs fuller research.

It is rarely mentioned in Blake studies that the other, very diff erent, part of Todd’s life distinct from the academic world of Blake scholarship was his involve-ment in the Surrealist moveinvolve-ment. Todd’s involveinvolve-ment with the Surrealists has never been recognized as having any signifi cance in relation to his Blake stud-ies, but these two worlds of Todd coincided in the 1940s. Long preceding the post-war impetus to academic study given by the publication of Northrop Frye’s Fearful Symmetry (1947) and David V. Erdman’s Blake: Prophet against Empire (1954), Blake was a popular name during the important 1936 International Sur-realist Exhibition in London, which was also a signifi cant encounter between Todd and the Surrealists. Th ere are many surprising similarities between Blake’s theory of conception and execution and the Surrealist manifestos. As the Surre-alists found their echoes in Blake and other preceding artists’ works, Surrealism in turn infl uenced Blake scholars through Todd’s relationship with the artists from the group.

Stanley William Hayter (1901–88), a prominent British printmaker of the twentieth century, was associated with the Surrealist group much earlier than Todd. His printmaking workshop, Atelier 17, was a major infl uence on many eminent modern artists, including Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró. With his new methods of engraving, Hayter spread Surrealist ideas of automatism and of the subconscious during the 1930s and 40s. It was in the workshop of Atelier 17, re-established in New York aft er moving from Paris, that Todd cooperated with Hayter and Miró in an experimental reconstruction of Blake’s processes of relief etching and printing.13 Th e similarity between Surrealist automatism and Blake’s

idea of the unity of invention and execution strongly suggests a connection between Surrealism, Todd’s experiments and the one-pull theory of Essick and Viscomi. Hayter was known as a strongly philosophical artist, one who held con-sidered theories about his artistic practices.14 Although experiments attempting

Despite their expertise in printmaking and Blake studies, the experiments of Todd, Hayter and Miró were largely discounted by Essick and Viscomi. Th e lat-ter two reconstructed Todd’s experiments but claimed that Todd was wrong in saying Blake used transfer techniques because Todd doubted Blake’s ability to do mirror writing.15 Essick and Viscomi established their authority with powerful

argument and historical and practical evidence. Nevertheless, Essick and Visco-mi’s notion of Blake’s unity of invention and execution, and his one-pull printing process, appear to have been inherited from Todd and his Surrealist background without acknowledgement.

Th e origin of one-pull and two-pull theories derives from Frederick Tatham and W. Graham Robertson.16 Both theories have little solid ground of proof.

Rob-ertson’s assertion of multiple printing was based on his own artistic observations; while Tatham’s description of Blake using one-pull method on his colour prints was from his fallible memory of distant conversations, bearing in mind that he was only three years old when Blake made his Large Colour Prints in 1795.

Th e analysis of technique presented by Essick and Viscomi has its own his-tory, which has been overlooked. Although Essick and Viscomi make reference to the experiments of etching and printing carried out by Ruthven Todd in the 1940s, they share with Todd a curious belief in the powers of automatic writing. Th e process of automatic writing was of enormous interest both to Todd and to the Surrealists of the 1920s and 30s. Th is appears to have prompted Todd’s inter-est in Blake as a possible automatic writer. Execution without premeditation, as Essick and Viscomi have described Blake’s relief-etching process, together with the legacy of Surrealist automatic writing has continued as a common feature in Blake studies from Todd’s time onwards. In other words, although Essick and Viscomi rejected Todd’s theories of Blake’s techniques, his legacy and the infl u-ence of the Surrealist group has been underestimated in the wider circle of Blake studies.

Ruthven Todd was the editor of Gilchrist’s Life of William Blake, published in 1942 for the Everyman’s Library, a new edition following Graham Robert-son’s earlier edition (London: John Lane, 1907). His Tracks in the Snow: Studies in English Science and Art (1946) and William Blake: the Artist (1971) were, in their time, two signifi cant historical research works on Blake and his contem-poraries. Th e Everyman’s Library edition of Alexander Gilchrist: Life of William Blake (1942) is the formal start of Todd’s work on Blake.17 Todd corrected

quota-tions from Blake which were changed for the reason that ‘another word seemed ‘“better”’.18 Anne Gilchrist, Dante Gabriel and William Michael Rossetti fi

a scholarly trend in favour of authenticating Blake’s writing. ‘Th e great industry of rewriting Blake’ at the end of the nineteenth century, Todd says, was ‘culmi-nating in the work of the late E. J. Ellis, who not only prepared a new text, but invented a new author for it, whom he called “the real Blake”’.19 Todd’s edition

was intended to restore the original text of Blake, which is a historical attempt followed up by other Blake scholars.

Todd’s Alexander Gilchrist: Life of William Blake of 1942 was revised in a second edition published in 1945 with expanded notes. For the next forty years, Todd continued collecting materials for a third edition of his Gilchrist. Th ese appear in three volumes now in the Special Material Department of the Brotherton Library, Leeds University (MS. 470.292–4). Th e copyright page is amended ‘COMPLETELY REVISED, 1968’ indicating that Todd worked on it almost until the end of his life. Th ere are leaves from Todd’s 1942 edition of Gilchrist, separated and pasted on large-sized paper, and bound in three albums, with Todd’s new addition of meticulous notes neatly handwritten in the margin. Th ey have never been published, although Todd tried hard to arrange publica-tion with the Clarendon Press.20 Th is is perhaps the most important work Todd

did on Blake. G. E. Bentley’s article, ‘Ruthven Todd’s Blake Papers at Leeds’ (1982), comments that ‘Th e work he [Todd] did was detailed and valuable, and much of it is new and fascinating. … Th ese fascinating materials for a new edition of Gilchrist are very extensive and very incomplete. Th ey deserve to be brought into order and up to date and published’.21 Bentley at that time had agreed to

serve as ‘midwife’ to the project if a publisher could be found. However, this never happened, and all the manuscripts of Todd on Blake studies, including his correspondence with many Blake scholars, were given to Leeds University Library by his son, Christopher Todd, a professor in the French Department of Leeds University.

Th e importance of Todd’s role in early Blake studies may be discerned in his contribution not only to re-editing Gilchrist’s references to Blake’s writing, but also to cataloguing Blake’s art. Not only did he correct Blake’s texts in Gilchrist’s edition used by Keynes and others,22 his catalogue of Blake’s paintings and

draw-ings later became the foundation for Martin Butlin’s Th e Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (1981), which is the defi nitive catalogue raisonné of Blake stud-ies. Todd says:

America, a revised and retyped copy of the catalogue and, since I did not know what to do with it, I gave it to the Library of Congress as everyone there had always been kind to me. As this contains much that is not in Geoff rey’s earlier version, I have now arranged for it to be lent to Martin Butlin. Th ese two vast tomes contain, apart from anything else, the results of reading my way through every auction catalogue I could fi nd from about 1790 on.23

In other words, as Butlin acknowledges, Todd made a major formative contri-bution towards the accumulation of the materials later assembled in Butlin’s catalogue raisonné.24 Although Butlin scrupulously acknowledged his debt to

Todd, it is probably the case that relatively few modern scholars will be aware that Ruthven Todd – as much as Sir Geoff rey Keynes – played a formative role in the foundation of Butlin’s catalogue. Eventually, much modern historical research of Blake’s text and image can be traced back to Todd. As his friend Julian Symons described it, Todd ‘was not especially interested in Blake as philosopher or mys-tic, but in his artistic achievement and his quality as a technical innovator’.25

Th e introductory note and the endnotes of Todd’s edition of Gilchrist’s Th e Life of William Blake show that he had close relations with many Blake schol-ars and was in frequent contact with them. Th ese included Geoff rey Keynes, Joseph Wicksteed, Graham Robertson, and W. E. Moss. Th e work of Anthony Blunt, a major British Blake scholar, was also an important reference for Todd.26

It appears that the experiments Todd did in 1947 with the Surrealist artists Wil-liam Hayter and Joan Miró in reconstructing Blake’s printmaking technique had their early inspiration at the time Todd re-edited Gilchrist’s biography of Blake in the early 1940s. He knew that Graham Robertson did experiments imitat-ing Blake’s colour printimitat-ing with his friend Newton Wethered around 1905, and perhaps Todd even saw Robertson’s ‘fake’ Blake, King of the Jews, which came near to being sold as an original at Sotheby’s until Robertson’s intervention.27

Th e colour print used Blake’s design in watercolour in an attempt at imitating Blake’s printing technique.28 In a letter of 26 November 1941, Graham

Robert-son wrote to KerriRobert-son Preston:

I’m so glad that Todd’s letter interested you and that you like his Toddity. So do I. Yes, he’s a whale for work, isn’t he? About the ‘King of the Jews’, Todd is here referring to my fake ‘colour print’ off ered for sale at Sotheby’s among the possessions of one Shaw and withdrawn at my request. I have the original watercolour and produced the ‘colour print’, not as a hoax but as an experimental attempt to imitate Blake’s queer process. Shaw bought it from Robert Ross, but as a W.G.R., not as a W.B. It looked so well, centred on the Sotheby wall, that I was quite sorry to expose it as a fraud. I wonder what became of it. It will probably fi gure as a Blake again some day, but it could easily be unmasked by the watermark on the paper.29

![Figure 1: Copper plate verso, An allegorical subject showing eight young girls circling a woman seated among clouds, and a print from the plate on silk, V&A Prints and Drawings [E.3266-1948/V.6b.I]](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/3928085.1871505/67.442.79.394.147.532/figure-copper-allegorical-subject-showing-circling-prints-drawings.webp)