Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI

TANJUNGPINANG, KEPULAUAN RIAU] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 18:36

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Online video modules for improvement in student

learning

Matthew Lancellotti, Sunil Thomas & Chiranjeev Kohli

To cite this article: Matthew Lancellotti, Sunil Thomas & Chiranjeev Kohli (2016) Online video modules for improvement in student learning, Journal of Education for Business, 91:1, 19-22, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1108281

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1108281

Published online: 23 Nov 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 19

View related articles

Online video modules for improvement in student learning

Matthew Lancellotti, Sunil Thomas, and Chiranjeev Kohli

California State University Fullerton, Fullerton, California, USA

The objective of this teaching innovation was to incorporate a comprehensive set of short online video modules covering key topics from the undergraduate principles of marketing class, and to evaluate its effectiveness in improving student learning. A quasiexperimental design was used to compare students who had access to video modules with a comparison group from otherwise identical classes. The profile of the students in the two groups was comparable, due in part to the large sample size. Evidence was found for significant improvement in learning across ethnic groups and gender, as measured by performance on a major exam.

KEYWORDS flipped; hybrid; learning improvement; marketing education; video

Introduction

Marketing faculty and other educators continually struggle to make the optimal use of classroom time to ensure that they not only impart the greatest amount of information, but that it is communicated in a way that is meaningful. As principles of marketing is a foundation course, a very large number of concepts need to be covered in limited class time, often resulting in rather shallow discussions. Further, there is continual pressure to add more information to the course, either to satisfy departmental or university goals and requirements, or to include the latest information on trends and advances in thefield. Students thus often have difficulty taking in all this information and retaining it—in essence, their learning is compromised. The innovation we tested in this study addresses these concerns, and was found to provide significant and real improvement in stu-dent learning.

Recent advances in technology have created many options for the instructors. Web-based classroom man-agement systems, such as BlackBoard and Moodle, have helped reduce the time faculty must spend on adminis-trative tasks such as dissemination of materials and grades (Ackerman, Chung, & Sun,2014). In-class clicker technology has facilitated classroom participation, espe-cially among students who might otherwise not actively engage in classroom discussions (Keough, 2012). Fur-ther, textbook companies have invested heavily in creat-ing digital learncreat-ing materials, such as interactive lessons, quizzes, and exercises, to accompany or even replace their printed textbooks. Such content, however, is gener-ally designed as a supplement to the content delivered by

the professor in the classroom, usually via lecture. The general expectation is that students will engage either in prelearning, by reviewing these materials before the classroom lecture, or they will reinforce their learning, by reviewing the materials post-lecture (McFarlin,2008). However, hard evidence on actual learning improvement is difficult to come by.

Hybrid learning andflipped classrooms

An alternative use of technology is to use it to replace or reduce in-class lectures, thus freeing up time in the class-room for more detailed discussions that—rather than reinforcing material through repetition—help to make it more meaningful and real (Sams & Bergmann, 2013). Such an approach has variously been referred to as a hybrid learning environment, or a flipped classroom. The central idea is that students use technology to learn basic concepts via technology before coming to class, so the classroom time can be used for more engaging activi-ties. Some initial studies of this technique have shown mixed results, depending on the outcome measures used (Haughton & Kelly,2015; Prashar,2015; Strayer,2012), whether student satisfaction is considered (Jackson & Helms, 2008), students’ personality and cognitive traits (Arispe & Blake, 2012), and the type of courses used (Estelami, 2012). It may be that transferring all or most lecture material outside the classroom creates other chal-lenges for some students, who may learn best when topics are explained by a professor in-person, especially when they can then question him or her about what is

CONTACT Matthew Lancellotti [email protected] California State University Fullerton, Department of Marketing, 800 N. State College Blvd., Fullerton, CA 92834, USA.

© 2016 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

2016, VOL. 91, NO. 1, 19–22

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1108281

presented. Further, research has shown that in a hybrid learning environment visual and audio materials are par-ticularly important to a successful learning process (Kilic-Cakmak, Karatass, & Ocak,2009).

We wanted to investigate if the use of short, concept-focused online video modules (hereafter referred to as video modules) would provide additional reinforcement of concepts to improve learning. In essence, rather than using videos to transfer the explanation of concepts largely out of the classroom, as in the classic fl ipped-classroom model, we wanted to see if topic-focused vid-eos that reinforce concepts from class lectures—using visual and audio communications together—would result in improved learning outcomes. For this study, we created a comprehensive set of 75 video modules—each lasting about 4–6 min—covering key concepts from the undergraduate principles of marketing course. These were posted online for students to view before coming to class, but also offered flexibility to students in viewing and reviewing them at their leisure. Rather than replac-ing or repeatreplac-ing entire lectures, each short video focused on one key topic covered during lectures.

Our objectives were two-fold: first, to evaluate whether the reinforcement of important concepts via viewing of the short online videos outside of class would enhance students’ performance. Further, as faculty in a large, diverse, public University, we have seen intractable disparities in learning outcomes among different student groups; in particular along ethnic and gender lines. In fact, a major initiative of the university is to reduce the gaps between student groups (e.g. average grades and graduation rates). Thus, a second objective of our study was to see whether the learning outcomes found in the study would differ based on factors such as gender or ethnic background. The expected effects are summarized in the following hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1(H1): Average student scores on would be higher when online videos are included in course content than when they are not.

Hypothesis 2(H2): Improvement in student scores as described inH1would be unaffected by (a) ethnic-ity, or (b) gender (gaps in learning will not be present; improvements will be effective across stu-dents groups).

Method

Four hundred seventy-nine students from a large West Coast university participated in the study. Student per-formance in principles of marketing classes from two previous semesters in which short online videos were not used (control group), was compared against the perfor-mance of students in a similar principles of marketing

class, where the only difference was the addition of access to the video modules (experimental group). The instructor and mode of instruction was the same, as were the assignments and exams. Further, the classroom and class times were kept the same, in an effort to attract a similar group of students, and make the groups compa-rable. A pure experiment with randomly created control groups was not possible due to the ethical implications of denying a control group of students access to online video modules, and the logistical difficulties in assigning large groups of students to specified class sections.

Student performance in the experimental group (247 students) was compared with student performance in the same course from two previous semesters (114 and 118 students; control group). The same instructor taught all three classes, and all other aspects of the course were identical including the exam questions. In both groups, students did not have access to the video modules for Exam 1. The control group did not have access to the video modules for Exam 2 either; but the experimental group did, and students in that group were asked to watch the video modules prior each class session. If the video modules had an impact, it would show up as improvement on Exam 2 scores.

Results

For comparison purposes it wasfirst necessary to deter-mine if the two control groups could be combined into a single group for analysis. Exam 1 scores were compared across section 1 and section 2 to determine if they were equivalent. An independent samplest-test (with Levene’s test for equivalency of variances) showed that means were not significantly different from each other (M1 D 37.61, M2 D 37.15), t (230) D 0.599, p D .550). Next, Exam 2 scores were compared across the first two sec-tions to determine if they were equivalent. An indepen-dent samplesttest (with Levene’s test for equivalency of variances) showed that means were also not significantly different from each other (M1 D 32.94, M2 D 32.51), t(230)D0.578,pD.564. Thereby, the two sections were combined into a single control group (ND232).

We then checked if students were comparable across the experimental and control group. For Exam 1, stu-dents in both the experimental and control group did not access the videos. We compared scores on this exam for both groups to see if they were equivalent. An inde-pendent samples t-test (with Levene’s test for equiva-lency of variances) showed that for Exam 1, the mean scores were not significantly different from each other (Mexe1D37.83,Mcge1D37.38),t(448)D0.935,pD.351. Thus, the two groups could be considered equivalent. 20 M. LANCELLOTTI ET AL.

Both the experimental and the control group did not have access to the video modules before Exam 1. Further, the control group did not have access to the videos for Exam 2, while the experimental group did. We observed that within the control group there was a decline in scores from Exam 1 (Mcge1D37.38) to Exam 2 (Mcge2D 32.72), because Exam 2 is inherently more difficult. It is important to make a note of this point, so as to reduce any confusion resulting from data interpretation.

If the videos had negligible impact, then the Exam 2 scores for the experimental group should also be low and equivalent to the Exam 2 scores from the control group. An independent samples t-test (with Levene’s test for equivalency of variances) showed that for Exam 2, the mean score was significantly higher for the experimental group (Mexe2 D 36.38,Mcge2 D32.72), t(477) D 7.332, p< .001). Thus, the videos had a significant impact on student performance.

We also wanted to see the impact on grades attained for the experimental group versus the control group. The overall chi-square test revealed no significant differences in grade distribution for Exam 1 between the two groups,

x2(4, N D479) D 4.0 pD.405, as expected, as neither

group watched the short videos prior to Exam 1

(seeTables 1and2).

For Exam 2, the overall chi-square test revealed a sig-nificant difference in the grade distribution between the two groups,x2(4, ND479)D 42.0,p<.001. This pro-vides support forH1.

From a practical, value added perspective, we were particularly interested in the failure rate (defined as the proportion of students receiving an F). We performed an additional analysis to check if the proportion of Fs in the

two groups were significantly different. The chi-square test revealed a significant difference in the proportion of Fs (27.2% vs. 9.7%), x2(1, ND 479)D24.48, p< .001.

Thus the failure rate dropped by about 62% (D1–24/ 63; 17.5% percentage points)—an impressive and signifi -cant amount—with the adoption of the videos, providing further support forH1.

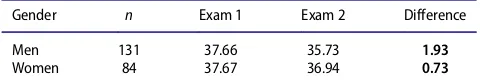

Further, we examined performance across the two exams for the experimental group based on gender and ethnicity, and compared them with the expected perfor-mance on the scores for the control group on the two exams. All ethnic groups showed a smaller decline in scores for Exam 2 in the experimental condition than would be expected based upon the control group (where expected score was the average score of the control group). This provides support for H2a. Analyses could not be conducted for African American students, as the sample size (4) was too small (seeTables 3and4).

A similar analysis was done for any differences based on gender. Both men and women showed less decline in scores for Exam 2 than expected (where expected score was the average score of the control group). This pro-vides support forH2b.

Overall the inclusion of video modules resulted in sig-nificant real improvement in students’ exam scores in principles of marketing. Students who had the option of watching a comprehensive set of short concept-focused videos performed significantly better on the exam.

Student satisfaction

Importantly, students themselves also acknowledged these advantages. In an effort to gauge student satisfac-tion with the addisatisfac-tion of video modules to their overall classroom experience, a survey was conducted in the course taken by the experimental group. Students were asked which mode of instruction they preferred. The

Table 1.Grade distribution for Exam 1.

Exam 1

Grade Control group Experimental group

A 21 (9.1%) 16 (6.5%)

Table 2.Grade distribution for Exam 2.

Exam 2

Grade Control group Experimental group

A 1 (0.4%) 8 (3.2%)

Table 3.Impact of ethnicity on exam scores.

Ethnicity n Exam 1 Exam 2 Difference

Caucasian 66 38.35 37.33 1.02 Asian American 61 37.90 35.41 2.49 Hispanic 68 37.16 36.27 0.89 African American 4 38.50 32.25 6.25 Other 13 36.31 35.38 0.93 Expected (Control group) 232 37.38 32.72 4.66

Table 4.Impact of gender on exam scores.

Gender n Exam 1 Exam 2 Difference

Men 131 37.66 35.73 1.93

Women 84 37.67 36.94 0.73

response rate was high (223 of 247, or just over 90%). Of those respondents 73.5% preferred lectures combined with online videos, 24.2% preferred traditional lectures, and 2.2% preferred online videos only. Thus, a majority of students found the video modules to be a valued sup-plement to, rather than simply a replacement for, instructor interaction.

Discussion

Based on these preliminary results, video modules should prove useful across a variety of marketing courses and a diverse spectrum of student characteristics, particularly since these improvements were found across ethnic groups and gender. However, further evaluation is neces-sary to fully assess their generalizability. Based on stu-dent feedback, the video modules were useful not just to prepare for the class, but also to reinforce concepts as part of a study plan, and increase their confidence in what they had learned. The short duration of the videos enabled students to review some difficult concepts multi-ple times, without having to sit through an entire (recorded) lecture. Further, the compact size of the mod-ules facilitated student access across a variety of devices, making it more convenient to watch and review the material in situations and environments in which the viewing of full-length lecture videos would be impractical or unpleasant.

This study is not without its limitations. Though efforts were made to control for differences between the control and experimental groups, it is entirely possible there were other factors beyond access to the video mod-ules that played a role in the improved performance on Exam 2 scores. Further, in the absence of formal track-ing, students were strongly encouraged to watch the video modules in the experimental condition. Other pro-fessors who may be less assertive in encouraging their use may have different outcomes—it is possible that by continually encouraging students to watch the videos students in the experimental condition, they were indi-rectly encouraged to simply study more than they might have otherwise. On the other hand, given students’ high levels of appreciation for the modules it is likely they would utilize them even with low levels of faculty encouragement.

A different—but not insignificant—limitation of the results presented here lies not with the analyses or results, but with the video modules themselves. The pro-duction of a comprehensive set of videos was a major endeavor. Although the technology to produce such vid-eos is widely and freely available at virtually all academic institutions, their production still required significant time and effort. As the outcome indicates, such time and effort is worthwhile, but our experience suggests their addition to the curriculum may be most practical for those courses that are taught by multiple faculty who can share in the necessary production efforts.

References

Ackerman, D., Chung, C., & Sun, J. C. (2014). Transitions in classroom technology: Instructor implementation of class-room management software.Journal of Education for Busi-ness,89, 317–323.

Arispe, K., & Blake, R. J. (2012). Individual factors and hybrid learning in a hybrid course.System,40, 449–465.

Estelami, H. (2012). An exploratory study of the drivers of stu-dent satisfaction and learning experience in hybrid-online and purely online marketing courses.Marketing Education Review,22, 143–155.

Haughton, J., & Kelly, A. (2015). Student performance in an introductory business statistics course: Does delivery mode matter?Journal of Education for Business,90, 31–43. Jackson, M. J., & Helms, M. (2008). Student perceptions of

hybrid courses: measuring and interpreting quality.Journal of Education for Business,84, 7–12.

Keough, S. M. (2012). Clickers in the classroom: A review and a replication. Journal of Management Education, 36, 822–

847.

Kilic-Cakmak, E., Karatass, S., & Ocak, M. A. (2009). An analy-sis of factors affecting community college students’ expecta-tions on e-learning. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education,10, 351–361.

McFarlin, B. (2008). Hybrid lecture-online format increases student grades in an undergraduate exercise physiology course at a large urban university. Advances in Physiology Education,32, 86–91.

Prashar, A. (2015). Assessing the flipped classroom in opera-tions management: A pilot study.Journal of Education for Business,90, 126–138.

Sams, A., & Bergmann, J. (2013). Flip your students’learning. Educational Leadership,70(6), 16–20.

Strayer, J. (2012). How learning in an inverted classroom infl u-ences cooperation, innovation and task orientation. Learn-ing Environment Research,15, 171–193.

22 M. LANCELLOTTI ET AL.