Growth Determinants

Laurence G. Weinzimmer

BRADLEYUNIVERSITYAlthough the management literature contains an impressive volume of several researchers have exclusively examined the influence of strategy factors on organizational growth (Donaldson, 1987;

studies attempting to identify factors that precipitate organizational

growth, fragmented theory has developed because of the absence of replica- Grinyer, McKiernan, and Yasai-Ardekani, 1988; Hamilton and Shergill, 1992; Johnson and Thomas, 1987). Others have

tive studies that integrate multiple levels of determinants. Previous studies

have shown that exclusive use of either industry, strategy, or top manage- examined relationships between characteristics of top manage-ment and organizational growth (Gupta, 1984; Hambrick and

ment determinants can individually influence sales growth, but no existing

research has empirically demonstrated the simultaneous effects of all three Mason, 1984; Norburn and Birley, 1988).

Several studies have tried to examine the impact of two

levels of determinants. Using a representative sample of 193 firms from

48 industries, this study replicated findings from several tangentially levels of determinants on organizational growth. Researchers

related studies to provide empirical support for the simultaneous influence have found concurrent effects of strategy and top management

of all three levels of determinants. Relative comparisons among the three characteristics on organizational growth (Feeser and Willard,

levels of determinants showed organization strategies to be most significant, 1990; Miller and Toulouse, 1986), strategy and industry

char-followed by top management characteristics and industry attributes. Inter- acteristics on organizational growth (McDougall, Robinson,

actions between industry/strategy determinants and strategy/top manage- and DeNisi, 1992; Romanelli, 1989), and industry and top

ment determinants were also found to be significant.J BUSN RES2000. management characteristics on organizational growth (Eisen-48.35–41. 2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. hardt and Schoonhoven, 1990). However, all of the studies that examined growth determinants at two levels used re-stricted samples such as single industry samples or samples consisting only of small businesses.

O

rganizations can benefit from growth in many ways, Although previous studies have shown that exclusive use including greater efficiencies through economies of of either industry, strategy, or top management attributes can scale, increased power, the ability to withstand envi- individually influence organizational growth, researchers have ronmental change, increased profits, and increased prestige yet to develop a unified model of organizational growth that for organizational members. A review of the management provides concurrent empirical support for all three levels of literature on organizational growth yields an extensive stream determinants. Moreover, limited attempts have been made to of research on consequences of growth, but only a limited investigate interactions among organizational growth determi-bibliography on determinants that precipitate growth. Al- nants.though earlier research has suggested a number of determi- In an attempt to combine growth determinants from tan-nants of organizational growth, strategy and organization the- gentially related studies into a single convergent model, find-ory researchers have been unable to gain consensus regarding ings from past research are replicated to develop a multilevel factors leading to organizational growth; therefore, creating model. We triangulate the simultaneous influences of industry fragmented theory (Davidsson, 1991; Kazanjian, 1990; Whet- attributes, portfolio-level and competitive-level organizational ten, 1987). strategies, and characteristics of top management teams by This lack of consensus may in part, result from the absence testing main effects, interaction effects, and relative compari-of replicative studies that attempt to integrate multiple levels sons among sets of determinants. In addition, to overcome of determinants to examine simultaneous effects. For example, sampling limitations from previous research examining multi-ple levels of determinants, this study uses a broad-based sam-ple of organizations from multisam-ple industries to increase the

Address correspondence to: Dr. L. G. Weinzimmer, Foster College of Business

Administration, Bradley University, Peoria, IL 61625, USA. generalizability of findings.

Journal of Business Research 48, 35–41 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

fies to define its domain (Bourgeois, 1980). Related

diversifica-Theoretical Framework

tion strategies build on synergies of existing businesses to The variables chosen to be replicated in this study are not achieve growth. Because related diversification is a growth intended to represent all possible growth determinants. Based strategy that builds upon existing synergies, a firm has existing upon an exhaustive review of the literature from 1985 to knowledge of the product and market in which it operates 1994, the variables replicated in this study comprise the most (Palepu, 1985). Conversely, if a firm undertakes an unrelated commonly studied determinants in the management literature diversification strategy, typically through acquisitions, the used to examine organizational growth. The journals reviewed firms will have limited knowledge, and, thus, will face increas-includeAcademy of Management Journal,Academy of Manage- ing uncertainty (Varadarajan and Ramanujam, 1987).

Re-ment Review,Administrative Science Quarterly,Entrepreneurship searchers have shown that related diversification strategies

Theory and Practice, Journal of Business Research, Journal of outperform unrelated diversification strategies in terms of

Business Venturing,Journal of Management,Journal of Manage- over-all performance, including growth; whereas unrelated

ment Studies,Journal of Small Business Management,Manage- diversification strategies decrease variability of sales growth

ment Science,Organization Science(1990 to 1994), andStrategic (Palepu, 1985).

Management Journal. Three sets of determinants were identi- Therefore, related diversification strategies should increase fied: industry attributes, organization strategies, and top-man- the likelihood of organizational growth relative to unrelated agement characteristics. diversification strategies, when controlling for acquisitions. This assertion does not imply that unrelated diversification will prevent a firm from achieving short-term growth. However, a

Industry Determinants of Growth

related diversification strategy will enable a firm to achieve a Such market characteristics as product differentiation, monop- higher growth rate than would an unrelated diversification olistic economies of scale, and capital requisites create barriers strategy.to entry; thereby, protecting incumbents from the threat of

COMPETITIVE-LEVEL STRATEGY. Competitive-level or

second-new entrants (Scherer, 1980). The model developed here

repli-ary strategies address how a firm competes within a particular cates studies that considered three common entry barriers:

industry (Bourgeois, 1980). Several researchers have sug-advertising intensity, research-and-development (R&D)

inten-gested or shown that strategic aggressiveness to pursue Porter’s sity, and competitive concentration. Advertising expenditures

(1980) competitive strategies is positively associated with or-raise barriers to entry by creating economies of scale thresholds

ganizational performance (Feeser and Willard, 1990; Grinyer, below which advertising impact would diminish. Similarly,

McKiernan, and Yasai-Ardekani, 1988; Romanelli, 1989). A R&D expenditures may deter new entrants by increasing

ini-firm can aggressively pursue a low-cost strategy by decreasing tial capital expenditures and creating a potentially complex

its cost base relative to competitors and pursue a differentiation knowledge base. Competitive concentration can also erect

strategy by offering a product or service perceived as unique entry barriers, because high concentration protects incumbent

by consumers. Aggressive firms may create such competitive firms from potential new entrants (Hamilton and Shergill,

advantages as increased customer awareness and brand loyalty 1992).

(Feeser and Willard, 1990). Romanelli (1989) suggested that When barriers to entry are high, firms within the industry

aggressive organizations had a better chance of surviving, have increased protection against the possibility that new

en-because aggressive firms will acquire the resources necessary trants may deplete the environment of critical resources

neces-to withstand competitive pressures and achieve growth. Thus, sary for existing firms to achieve growth. Therefore, firms

aggressive strategies should lead to increased growth. located in an industry with high entry barriers are expected

to achieve higher levels of growth relative to firms located in

industries with low entry barriers.

Top Management Determinants of Growth

In the organization theory and strategy literatures, beliefs and characteristics of powerful individuals in organizations are

Strategy Determinants of Growth

thought to have a pronounced impact on the initiation of Researchers have shown that organizational strategies are im- strategic change and organizational growth. Specifically, this portant determinants of organizational success (Feeser and study replicates research initiated by Hambrick and Mason Willard, 1990; Grinyer, McKiernan, and Yasai-Ardekani, (1984) and Gupta (1984). These authors contended that top 1988; Palepu, 1985). This study replicates findings from two management team (TMT) characteristics that may influence central approaches to organizational strategy: portfolio-level organizational growth include heterogeneity and age of the strategies and competitive-level strategies top management team.

PORTFOLIO-LEVEL STRATEGY. Portfolio-level or primary strat- HETEROGENEITY OF TOP MANAGEMENT TEAMS. Eisenhardt

diversi-ity of top management team members produces constructive Manual, Moody’s Unlisted OTC Manual and Dun and Brad-street’s Reference Book of Corporate Managements. All firms conflict. They argued that this form of heterogeneity would

provide better decision making, because TMT members with on the COMPUSTAT database reporting quarterly figures for sales, advertising expenditures, and research and development many years in a particular industry can offer insights based

upon rich experience; whereas, newcomers can provide fresh expenditures for 20 consecutive quarters from the first quarter of 1987 to the fourth quarter of 1991, and reporting top perspectives. Additionally, heterogeneity of functional

experi-ence may affect the growth rate of an organization. Functional management data were included in the sample. This yielded a sample of 193 firms from 48 industries, based upon primary heterogeneity can produce constructive conflict, wherein team

members with different functional backgrounds provide Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes. Power analysis (Cohen, 1977) indicated that a minimum of 168 firms would checks and balances in decision making (Hambrick and

Ma-son, 1984). Therefore, organizational growth may be posi- be needed for this study. tively related to the level of top managers’ industry and

func-tional heterogeneity.

Measurement of Variables

To replicate previous research, this study operationalized

AGE OF TOP MANAGEMENT TEAM MEMBERS. Hambrick and growth variables using measures commonly found in the

orga-Mason (1984) proposed that age of the upper echelon would nization theory and strategy literatures. affect the growth rate of an organization, where older

execu-ORGANIZATIONAL GROWTH. This study used a modified

ver-tives tend to be more conservative and have a bias for

main-sion of the ordinary least-squares beta coefficient approach taining the status quo. Perhaps executives in the latter years

used by Grinyer, McKiernan, and Yasai-Ardekani (1988) and of their careers would not feel as mobile as younger executives

Hamilton and Shergill (1992) over 20 quarterly observations and, therefore, would not want to take the risks often necessary

(adjusted for seasonality) to measure sales growth. Sales data when seeking to increase firm growth. Younger executives

were chosen for reasons of replicability, because most recent typically take more risks, so youthfulness of executives leads

studies in our literature review used sales data to measure to organizational growth (Hambrick and Mason, 1984).

growth. In addition, the beta coefficient approach was chosen as the appropriate operationalization, because it captures the

Control Variables

fine-grained fluctuations of sales data better than other meth-An organization’s growth rate is closely related to the growth ods commonly used to measure growth, and it dampens the rate of its industry (Kotha and Nair, 1995). Therefore, this effects of outliers (Weinzimmer, Nystrom, and Freeman, study controls for industry growth rates, because the sample 1998). Growth rates were also standardized for the size of uses firms from multiple industries. In addition, the number each organization by dividing the beta coefficient by the mean of companies acquired and/or sold during the period of obser- size of an organization over the period of observation (cf. Dess vation was considered as a control variable for the diversifica- and Beard, 1984; Grinyer, McKiernan, and Yasai-Ardekani, tion measure, because organizations may grow or decline sim- 1988). Therefore, the estimated slope of the regression line ply because of acquisitions or divestitures. Organizational (b9) of sales over time represents the rate of change (growth) slack, defined as excess assets after debts have been satisfied, of an organization. Specifically, growth is operationalized as was also considered as a control variable. Eisenhardt and (Equation 1).Schoonhoven (1990) showed that organizational slack was positively related to growth. Although previous studies have not been able to show

the simultaneous effects of all three levels of determinants,

replicating findings from tangentially related research provides where:GRWj5growth rate forjth firm;Zij5sales of thejth a strong theoretical foundation for examining these simultane- firm the ith period;i5 time period; di 5 discount rate for ous influences. Therefore, to extend previous research, we inflation during theith period;mzjdi5 mean size of the jth examine the proposition that organizational growth is influ- firm, discounted for inflation; and,n520 consecutive quar-enced simultaneously by industry attributes, organizational ters from 1987 to 1991.

strategies, and TMT characteristics.

ENTRY BARRIERS. A composite score was calculated for each

four-digit SIC code using advertising intensity, R&D intensity, and a four-firm concentration ratio. Entry barrier measures

Methods

may not be comparable among different industries, given

char-Data Collection Methods

acteristics endogenous to different markets. Therefore, these measures were standardized before the variables were summed Data were collected from multiple sources: Standard & Poors’COMPUSTAT data tapes,Standard & Poors’ Corporate Records, to calculate height of entry barriers (cf. McDougall, Robinson, and DeNisi, 1992).

PORTFOLIO-LEVEL STRATEGY. This study uses Davis and Du- process was used to adjust for multicollinearity (cf. Berry and Feldman, 1990). Means, standard deviations, and correlations haime’s (1992) entropy measure of diversification to

inves-tigate the influences of related diversification from 1987 of variables are presented in Table 1. to 1991.

STRATEGIC AGGRESSIVENESS. This study used Fombrun and

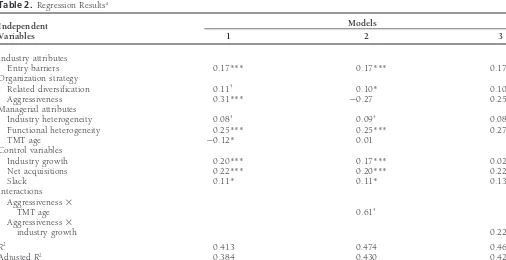

OLS Multiple Regression Analysis

Ginsberg’s (1990) composite approach to measure strategicTable 2 presents OLS regression results. Model 1 tests for the aggressiveness. To calculate differentiation aggressiveness,

ra-simultaneous effects of all three levels of determinants, and tios of advertising expenditures to sales and product R&D

Models 2 and 3 test for interaction effects. Multiple regression expenditures to sales were used. To calculate low-cost

aggres-results from Model 1 show a significant positive association siveness, ratios of expenditures for new plant and equipment

between organization growth and industry entry barriers (p,

to sales and process R&D expenditures to sales were used.

0.001), suggesting that an industry with high entry barriers Industry effects were controlled by dividing firm ratios by

will lead to organizational growth. Results for strategy-level average industry ratios to assess firm-level aggressiveness

rela-determinants in Model 1 show a significant positive association tive to competition.

between organizational growth and related diversification (p,

HETEROGENEITY OF TOP MANAGERS. Top managers are de- 0.05) and strategic aggressiveness (p , 0.001), suggesting

fined as all officers above the level of vice president (Michel that strategies pursued by a firm are significant in explaining and Hambrick, 1992). Industry heterogeneity was measured growth. Finally, the data suggest strong empirical support for by computing the coefficient of variation, defined as the stan- several top management team determinants, including signifi-dard deviation divided by the mean (cf. Wiersema and Bantel, cant positive associations between organizational growth and 1992). Functional heterogeneity was measured by the number the degree of TMT heterogeneity in terms of industry experi-of functional disciplines currently represented by top manage- ence (p,0.10), the level of TMT heterogeneity in terms of ment members divided by the size of the TMT using a nine- functional backgrounds (p,0.001) and a significant negative point scale offered by Michel and Hambrick (1992). association between organizational growth and average age of

the TMT (p, 0.05).

AGE. Age is measured by mean age in years of top managers Model 2 shows a significant positive relationship between (Norburn and Birley, 1988). growth and the multiplicative interaction between

aggressive-ness and TMT age. Similarly, Model 3 shows a significant

CONTROL VARIABLES. To measure industry growth, sales for

positive relationship between growth and the multiplicative each 4-digit SIC code were regressed over time and the

corre-interaction between aggressiveness and industry growth. sponding standardized coefficient (b9) was used as a measure

of industry growth (cf. Dess and Beard, 1984). Organization slack was measured as assets/debt (Eisenhardt and

Schoonho-Relative Effects Among Different Levels

ven, 1990). Net acquisitions/divestitures for each organizationwas a continuous variable, ranging from2ntonacquisitions

of Determinants

during the period of 1987–1991. Given the strong empirical evidence for the simultaneous in-fluence of all three levels of determinants, highlighting the relative importance for each level of determinants may provide

Analytic Procedures

additional insights. To determine the relative importance ofone set of determinants over another, we used ax2-test

proce-To replicate findings from previous research, this study used

dure replicating methods used by other researchers comparing multiple-lagged ordinary least-square (OLS) regression

analy-the relative importance of variables to each oanaly-ther (cf. Kotha sis to recognize the effects of time, because all previous growth

and Nair, 1995). studies used correlation or regression analysis to test the

signif-Each of the three levels of determinants provided significant icance of determinants. To ensure that the OLS multiple

re-improvements over the base model consisting of the control gression model fit the dataset, comprehensive diagnostic tests

variables. However, strategy-level determinants provided the were performed to check for both randomness and normality

largest improvement (Dx2 5 87.43; p , 0.001; adj-R2 5

of the residuals (cf. Weinzimmer, Mone, and Alwan, 1994).

0.27), followed by top management team level determinants (Dx2551.49;p,0.001; adj-R250.25) and industry-level

determinants (Dx2511.05;p,0.005; adj-R250.17). This

Results

organi-Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlationsa

Variable Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1. Firm growth 1.13 2.60

2. Entry barriers 0.12 0.15 0.23**

3. Diversification 0.05 0.28 0.11* 0.10

4. Aggressiveness 0.46 0.70 0.39** 0.11* 20.01

5. Industry heterogeneity 1.98 1.28 0.13* 20.12* 0.05 0.02

6. TMT age 51.33 5.23 20.25** 20.03 20.01 20.12* 20.02

7. Functional heterogeneity 0.65 0.19 0.32** 0.03 0.02 0.09 0.14* 20.17* 8. Industry growth 6.02 8.65 0.22** 20.08 0.03 0.03 0.11* 20.14 0.01

9. Net acquisitions 1.21 2.34 0.26** 0.11* 20.09 0.12* 0.01 0.00 20.03 0.01

10. Slack 26.36 35.07 0.11* 0.06 0.01 20.04 20.09 20.16* 0.04 20.07 20.03

an5193.

*p,0.05. **p,0.001.

zational growth, in terms of explained variance, as compared eralizable sample. However, no research has demonstrated the concurrent effects of all three levels of determinants. There-to any of the restricted models.

fore, findings from this study in some ways contradict previous research that studied the effects of industry, strategy, and top

Discussion

management variables in explaining organizational growth.Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven (1990) concluded that, although Previous studies have shown that either industry, strategy, or

top management attributes individually influence organiza- industry and managerial factors influence organizational growth, strategy characteristics do not. A possible explanation tional growth. Using measures and analytic methods from

previous research, this study replicated these findings and for inconsistencies between this study and Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven’s (1990) study is these authors only used a confirmed many of these individual relationships using a

gen-Table 2. Regression Resultsa

Models Independent

Variables 1 2 3

Industry attributes

Entry barriers 0.17*** 0.17*** 0.17***

Organization strategy

Related diversification 0.11† 0.10* 0.10†

Aggressiveness 0.31*** 20.27 0.25***

Managerial attributes

Industry heterogeneity 0.08† 0.09† 0.08†

Functional heterogeneity 0.25*** 0.25*** 0.27***

TMT age 20.12* 0.01

Control variables

Industry growth 0.20*** 0.17*** 0.02

Net acquisitions 0.22*** 0.20*** 0.22***

Slack 0.11* 0.11* 0.13**

Interactions Aggressiveness3

TMT age 0.61†

Aggressiveness3

industry growth 0.22†

R2 0.413 0.474 0.463

AdjustedR2 0.384 0.430 0.421

F 14.31*** 10.73*** 10.98***

an5193. †p,0.10.

single measure for strategy, technological innovation. This 1989). This study, however, presents the first evidence for a relationship between strategy and industry growth fit on study found both portfolio-level and competitive-level

strate-gies to be significant in explaining growth. Similarly, Kotha organizational growth. This finding suggests that certain strat-egies align a firm better with a particular industry, and, and Nair (1995) found environmental-level variables to be

significant in explaining growth, but concluded that strategy thereby, enable it to achieve growth. variables had no impact on growth. A possible explanation

for this inconsistency is that these authors used

single-dimen-Conclusion and Directions for

sional measures for strategy, including individual measures

for efficiency, capital expenditures (low-cost strategies), and

Future Research

advertising intensity (differentiation strategy). Our study usedAlthough the replication approach used in this study provided a multidimensional measure of strategic aggressiveness from

support for previously identified relationships between growth a composite of both low-cost and differentiation strategies.

and individual levels of determinants, contributions from this Hill (1988) showed that concurrent pursuit of both low-cost

study come from the theoretical and empirical convergence and differentiation strategies can create competitive advantage.

of previously tangentially related studies to provide a unified Therefore, when examining determinants of organizational

explanation of organizational growth. This study was able to growth, a composite aggressiveness measure may capture

show simultaneous effects for all three levels of determinants over-all strategic orientation better than individual measures.

using a triangulation approach—including tests of main ef-fects, interactions, and relative comparisons among sets of

Interactions of Determinants

determinants.egy–Structure Fit and Financial Performance in New Zealand:

growth, these models suffer a deficiency, because the

determi-Evidence of Generality and Validity with Enhanced Controls.

nants precipitating growth are, at best, implied. Additionally,

Journal of Management Studies29 (1992): 95–113.

because our study did not discriminate between growing and

Hannan, M. T., and Ranger-Moore, J.: The Ecology of Organization

declining firms, where growth could be either positive or Size Distributions: A Microsimulation Approach.Journal of Mathe-negative, findings may also contribute to the organizational matical Sociology15 (1990): 65–89.

decline literature. Hill, C. W.: Differentiation versus Low Cost of Differentiation and

Low Cost: A Contingency Framework. Academy of Management Review13 (1988): 401–412.

References

Johnson, G., and Thomas, H.: The Industry Context of Strategy, Baum, J. A., and Mezias, S. J.: Competition, Institutional Linkages,

Structure, and Performance: The U.K. Brewing Industry.Strategic and Organizational Growth.Social Science Research22(1) (1993):

Management Journal8 (1987): 343–361. 131–164.

Kazanjian, R. K.: Relation of Dominant Problems to Stages of Growth Berry, W. D., and Feldman, S.:Multiple Regression in Practice. Sage

in Technology-Based New Ventures.Academy of Management Jour-University Paper #50, Sage, Newbury Park, CA. 1990.

nal31 (1990): 257–279. Bourgeois, L. J.: Strategy and Environment: A Conceptual Integration.

Kotha, S., and Nair, A.: Performance Determinants in the Japanese Academy of Management Review5(1) (1980): 25–39.

Machine Tool Industry.Strategic Management Journal16 (1995): Cohen, J.:Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Aca- 497–518.

demic Press, NY. 1977.

McDougall, P., Robinson, R., Jr., and DeNisi, A. S.: Modeling New Davidsson, P.: Continued Entrepreneurship: Ability, Need, and Op- Venture Performance: An Analysis of New Venture Strategy, In-portunity as Determinants of Small Firm Growth.Journal of Busi- dustry Structure, and Venture Origin.Journal of Business Venturing

ness Venturing6 (1991): 405–429. 7 (1992): 267–289.

Davis, R., and Duhaime, I. M.: Diversification, Vertical Integration, Michel, J., and Hambrick, D.: Diversification Posture and Top Man-and Industry Analysis: New Perspectives Man-and Measurement.Stra- agement Team Characteristics. Academy of Management Journal

tegic Management Journal13 (1992): 511–524. 35 (1992): 9–37.

Dess, G. G., and Beard, D. W.: Dimensions of Organizational Task Miller, D., and Toulouse, J.: Strategy, Structure, CEO Personality, Environments. Administrative Science Quarterly 29(1) (1984): and Performance in Small Firms.American Journal of Small Business

52–73. (Winger 1986): 47–61.

Donaldson, L.: Strategy and Structural Adjustment to Regain Fit Norburn, D., and Birley, S.: The Top Management Team and Corpo-and Performance: In Defense of Contingency Theory.Journal of rate Performance.Strategic Management Journal9 (1988): 225–

Management Studies24(1) (1987): 1–24. 237.

Eisenhardt, K. M., and Schoonhoven, C. B.: Organizational Growth: Palepu, K.: Diversification Strategy, Profit Performance, and the En-Linking the Founding Team, Strategy, Environment, and Growth tropy Measure.Strategic Management Journal6 (1985): 239–255. Among U.S. Semiconductor Ventures, 1978–1988.Administrative

Porter, M.:Competitive Strategy. Free Press, New York. 1980. Science Quarterly35 (1990): 504–529.

Romanelli, E.: Environments and Strategies in Organization Start-Evans, D. S.: Tests of Alternative Theories of Firm Growth.Journal ups: Effects on Early Survival.Administrative Science Quarterly34

of Political Economy95 (1987): 657–674. (1989): 369–387.

Feeser, H. R., and Willard, G. E.: Founding Strategy and Performance: Scherer, F.: Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance, A Comparison of High and Low Growth Firms.Strategic Manage- 2nd ed. Houghton Mifflin, Boston. 1980.

ment Journal11 (1990): 87–98.

Varadarajan, P., and Ramanujam, V.: Diversification and Perfor-Fombrun, C. J., and Ginsberg, A.: Shifting Gears: Enabling Change mance: A Re-examination Using a New Two-Dimensional Con-in Corporate Aggressiveness. Strategic Management Journal 11 ceptualization of Diversity in Firms.Academy of Management

Jour-(1990): 297–308. nal30 (1987): 380–393.

Grinyer, P. H., McKiernan, P., and Yasai-Ardekani, M.: Market, Orga- Weinzimmer, L. G., Mone, M. A., and Alwan, L. C.: An Examination nizational, and Managerial Correlates of Economic Performance of Perceptions and Usage of Regression Diagnostics in Organiza-in the U.K. Electrical EngOrganiza-ineerOrganiza-ing Industry.Strategic Management tion Studies.Journal of Management20(1) (1994): 179–192. Journal9 (1988): 297–318.

Weinzimmer, L. G., Nystrom, P. C., and Freeman, S. J.: Measuring Gupta, A. K.: Contingency Linkages Between Strategy and General Organizational Growth: Issues, Consequences, and Guidelines.

Manager Characteristics: A Conceptual Examination.Academy of Journal of Management24(2) (1998): 235–262.

Management Review9 (1984): 399–412. Whetten, D.: Organizational Growth and Decline Processes.Annual Hambrick, D. C., and Mason, P.: Upper Echelons: The Organization Review of Sociology13 (1987): 335–358.

as a Reflection of Its Top Managers. Academy of Management Wiersema, M., and Bantel, K.: Top Management Team Demography

Review9 (1984): 193–206. and Corporate Strategic Change.Academy of Management Journal