COVERING COMPLEX RELATIONSHIPS

A New Institutional Approach to United States International News Reporting

複雑化国家間関係に関する報道

米国に関する国際報道の新制度的アプローチ

A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Troy Keith Knudson

4006S302-6

Graduate School of Asia Pacific Studies

Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan

Form HE (S→O)

GSAPS SUMMARY OF DOCTORAL THESIS

COVERING COMPLEX RELATIONSHIPS

- A New Institutional Approach to United States International News Reporting -

4006S302-6 Troy Keith Knudson Chief Advisor: Prof. Hatsue Shinohara Keywords: New institutionalism, journalism, international news, foreign policy making

The main objective of this study was to test the applicability of the new institutional approach to international political news reporting. Recent research incorporating news reports as aspects of political communication has emphasized the necessity of building comprehensive models that coherently integrate the antecedents and effects or correlates of news content. New institutionalism has provided theoretical concepts for the building of such a model regarding political reporting about United States domestic issues. Namely, Sparrow and Cook have traced the historical trajectory of normative constraints related to the professionalization, homogenization, and legitimization of journalistic behaviors as evidence for their argument that the news media comprise a homogeneous political institution.

These constraints are argued by Sparrow to stem from the political economy of the highly commercialized news industry, and by Cook to stem from the political culture of professional political reporting as a perceived function of democracy. Even though their two streams of logic lead these scholars to separate conclusions regarding the outcome of homogeneous political news reporting, their conclusions are not incompatible. While Sparrow concluded that economic constraints disallow the intended democratic function of the press to thrive, Cook concluded that cultural constraints lead to a political system of government by publicity, a concept suggesting that political news serves a democratic function not by facilitating balance between the three branches of government but by facilitating the flow of intragovernmental communication.

Nevertheless, this framework has almost exclusively been used to explain news reporting about domestic affairs; news focusing on international affairs and United States foreign policy has received little scholarly attention from an institutional or other comprehensive approach. This study argues that international news research has yet to integrate two camps separately investigating what goes into the creation of news content and the potential political consequences of that content.

Related to the different states of research development regarding domestic and international political news are differences between the occupational and professional environments within which news is created. The most fundamental of such differences are the comparative lack of democratic processes by which foreign policy is made and, therefore, the lack of democratic space available for news reporting.

In order to account for these differences, this study established three methodological standards, based on Cook’s three criteria for considering the news media as an institution, as guidelines for the selection of the case employed, the data gathered, and the methods by which the data was analyzed. It was determined that an institutional approach to investigating international news reporting and its relevance to foreign policy making would require a theoretical framework that employs a context-based case study on routine coverage about a country or group of countries toward whom United States foreign policy is both sufficiently complex and sufficiently complicated, offers a conceptualization of the news media that neither underrepresents the actual environment of news organizations reporting international news nor prematurely conflates these organizations without properly establishing sufficient similarities between them, and

emphasizes the intragovernmental communicative aspect of news coverage within the foreign policy making process.

United States foreign policy toward China from May 27, 1994 to May 24, 2000, during which the main issue was the annual granting of the most favored nation trade status, was selected as the case. News coverage from the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Associated Press, which all maintained bureaus in Shanghai and Beijing throughout the entire period, were utilized as sources of news coverage. Data related to the political activities of the United States Congress was gathered in order to observe possible evidence of the facilitation of intragovernmental communication from the executive to the legislative branch. One- and independent-sample t-tests, independent binomial tests, simple regressions, and analyses of the significance of differences between correlation coefficients were conducted in order to determine whether a comprehensive model and/or an institutional framework could be applied to this case.

It is concluded that, in its entirety, the current institutional framework suggesting that the homogeneity of coverage from various news organizations can explain the political functionality of coverage as a means of intragovernmental communication is inapplicable in this case. However, some aspects of the framework (e.g., those related to normative journalistic constraints and the concept of government by publicity) were found to be applicable when tested individually. Specifically, in the case considered here it was revealed that the intragovernmental communicative function of news coverage was best explained by the prominence of coverage. As prominence is determined by news organizations individually, it is concluded that a combination of elements from the organizational and institutional approaches would yield the most applicable comprehensive model for international news reporting. It is therefore recommended that future studies find ways to integrate differences between news organizations into their conceptual frameworks.

References

Cook, Timothy E. 2005. Governing with the news: The news media as a political institution. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing media systems:

Three models of media and politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mead, Walter Russell. 2002. Special providence: American foreign policy and how it changed the world. New York: Taylor and Francis Books. Riffe, Daniel, Stephen Lacy, and Frederick G. Fico. 2005. Analyzing media

messages: Using quantitative content analysis in research. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Seib, Philip. 1997. Headline diplomacy: How news coverage affects foreign policy. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Shoemaker, Pamela J., and Stephen D. Reese. 1996. Mediating the message: Theories of influences on mass media content. 2nd. ed. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Sparrow, Bartholomew H. 1999. Uncertain guardians: The news media as a political institution. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

iv

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments vi

List of Tables viii

Introduction 1

Chapter 1 United States News Media as a Political Institution 9

1.1 New Institutionalism Theory 9

1.1.1 Sociological Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis 12

1.1.2 Political Science Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis 15

1.1.3 Legitimacy and Homogeneity in Organizational Analysis 18

1.2 Institutional Interpretations of Political News Reporting 20

1.2.1 Media Commercialization and the Professionalization of Journalism 25

1.2.2 Three Concepts of Press Independence 30

1.2.3 Symbiosis between Journalists and Government Officials 36

1.2.4 Facilitator of Intragovernmental Communication 42

Chapter 2 International News and the Foreign Policy Making Environment 47

2.1 Applying the Institutional Framework to International News 48

2.1.1 Normative Constraints on International News Reporting 51

2.1.2 Constraints as Homogenizers of News Content 57

2.1.3 Constraints as Enablers of a Democratic Function 60

2.1.4 Theoretical and Methodological Contributions of This Study 63

2.2 Methodologies of Previous International News Studies 67

2.2.1 Explorations of Influence through Interviews and Historical Analyses 68

2.2.1.1 Foci on Behavior and Interaction 69

2.2.1.2 Descriptions of Normative Media Influence 72

2.2.2 Explorations of Influence through Counting Content Items 77

2.2.2.1 Foci on Journalistic Norms 78

2.2.2.2 Comparisons of Media and Governmental Attention 82

v

2.3.1 Missing an Intragovernmental Communicative Aspect of Reporting 88

2.3.2 Missing Case Studies on Sufficiently Complex Foreign Policies 89

2.3.3 Conflated/Underrepresented Conceptualizations of News Media 94

Chapter 3 Research Design 98

3.1 Case Study on a Sufficiently Complex Foreign Policy 101

3.2 News Organizations Considered Individually 108

3.3 Focus on Intragovernmental Communication 118

Chapter 4 Analytical Results 126

4.1 Research Question Pair 1 127

4.1.1 Testing the Hegemony Thesis 128

4.1.1.1 Testing Hypothesis 1.1A 129

4.1.1.2 Testing Hypothesis 1.1B 137

4.1.2 Testing the Commercial Media Thesis 144

4.1.3 Research Question 1.2 148

4.2 Research Question Pair 2 149

4.2.1 Research Question 2.1 151

4.2.2 Research Question 2.2 154

Chapter 5 Conclusion 157

Appendix 1 Public Statements of Official Changes to Policy toward China 166

Appendix 2 Policy Tenets in News Coverage and Congressional Discourse 177

Appendix 3 Code Sheets 184

vi

Acknowledgments

The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without help from a number of individuals and academic organizations. I would first like to thank Professor Hatsue Shinohara at the Graduate School of Asia Pacific Studies (GSAPS) at Waseda University for allowing me to join her doctoral seminar halfway into my research, after the current study’s main objective had already been fixed. I gained a lot by observing the historical approaches to research taken by her students of international relations. Professor Shinohara also deserves credit for much of the encouragement that pushed me toward completing this dissertation after I had started teaching.

I would like to thank Professor Shigeto Sonoda at the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia at the University of Tokyo for first accepting me into his doctoral seminar at GSAPS even though my research plan seemed likely to evolve at almost every meeting. I would like to thank him for his patience in enduring the gradual development of my academic ideas. Many of my assumptions as a social scientist developed while observing and commenting on presentations given by the variety of social researchers that comprise Professor Sonoda’s seminar. I would also like to thank Professor Thomas Joseph Cogan at the School of Social Sciences at Waseda University and Professor Kaori Hayashi at the Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies at the University of Tokyo for providing clear assessments of the research plan during the interim examination as well as the final results during the oral defense. I have responded to the concerns and recommendations they expressed regarding my research to the best of my ability in this final version of the dissertation.

Many of the activities necessary for conducting the research reported here were funded by two Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) awarded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). With this funding, I was able to purchase materials necessary for conducting the review of literature and the software for conducting the statistical analyses. These grants also allowed me to employ two master’s degree students from GSAPS to code the content items used in this study’s analyses. I would like to thank Marna Romanoff and Hamilton Shields for enduring such tedious work. Obviously, there would have been no data for me to analyze without their contribution.

I received an additional research grant, as well as a great deal of academic experience, from the Global Institute for Asian Regional Integration (GIARI) Global Center of

vii

Excellence Program at Waseda University, which recommended me as a JSPS doctoral fellow and which employed me as a research assistant before and after my fellowship with JSPS. With the research grant provided by GIARI, I was able to participate in the 2008 Summer Institute conducted by the Elliot School of International Affairs at George Washington University. Many of the ideas in this dissertation related to the conducting of United States foreign policy, as well as how news organizations write about it, were developed during the weeks I spent in Washington D.C. attending this program.

Additionally, I would like to thank all of the doctoral students at GSAPS who have been affiliated with the Waseda University Doctoral Student Network, which I co-chaired for three years. I have learned a lot about my place and responsibility within the academic community through our events and informal exchanges.

As parts of this dissertation were written after I had started my first academic position as a lecturer at Kobe University, I would like to thank all of the faculty, staff, and students at the School of Law and Graduate School of Law for providing me with the space and time to complete this project.

Finally, I would mostly like to thank my two families in Japan and the United States for supporting me through every step of the research that appears here. I understand fully that the time I spent working on it was time when they had to work twice as hard.

Troy Keith Knudson February, 2012

viii

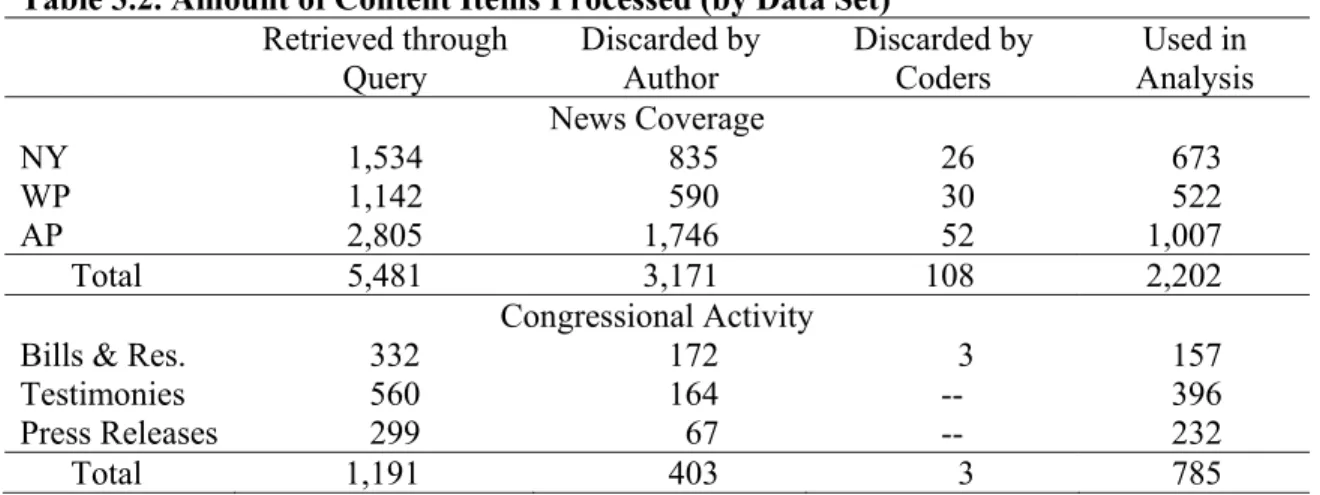

List of Tables

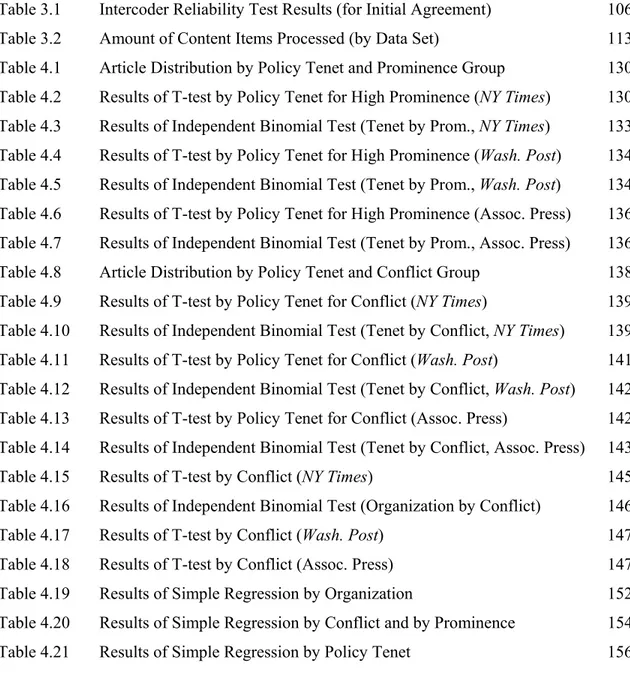

Table 3.1 Intercoder Reliability Test Results (for Initial Agreement) 106

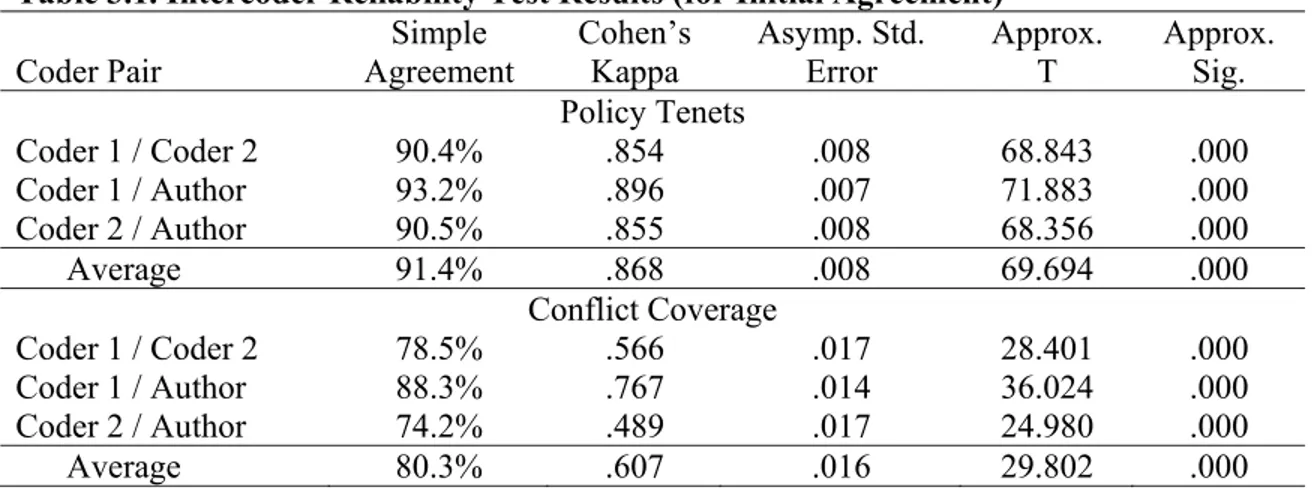

Table 3.2 Amount of Content Items Processed (by Data Set) 113

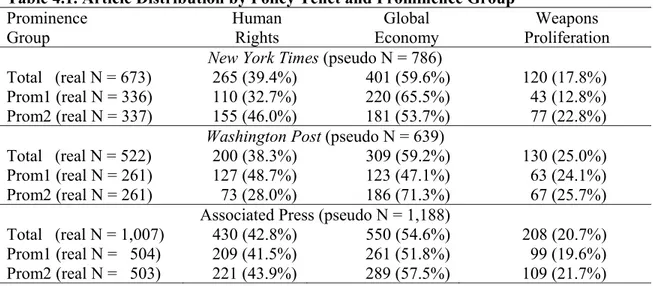

Table 4.1 Article Distribution by Policy Tenet and Prominence Group 130

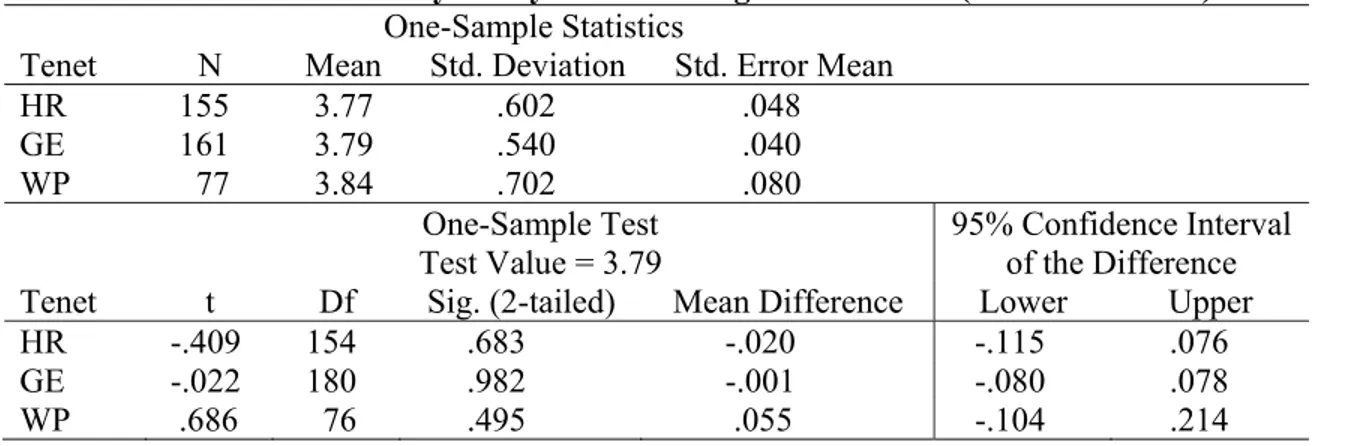

Table 4.2 Results of T-test by Policy Tenet for High Prominence (NY Times) 130

Table 4.3 Results of Independent Binomial Test (Tenet by Prom., NY Times) 133

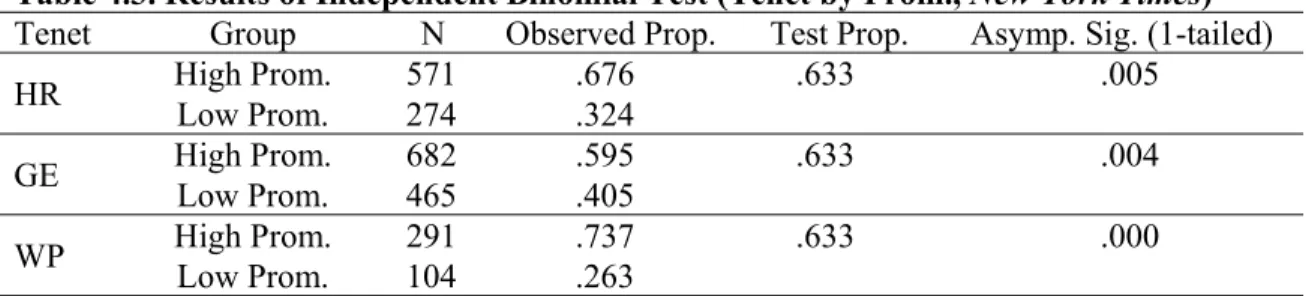

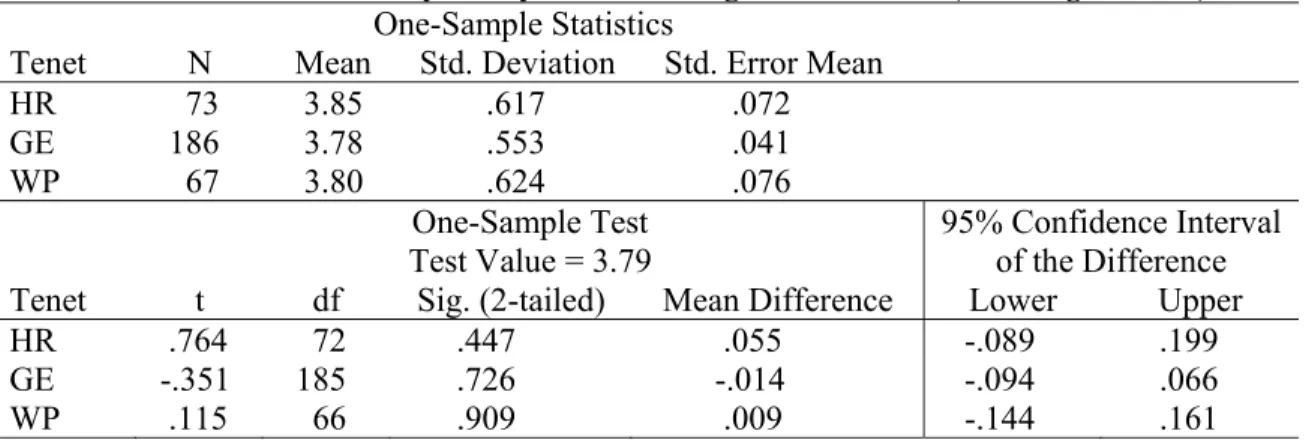

Table 4.4 Results of T-test by Policy Tenet for High Prominence (Wash. Post) 134

Table 4.5 Results of Independent Binomial Test (Tenet by Prom., Wash. Post) 134

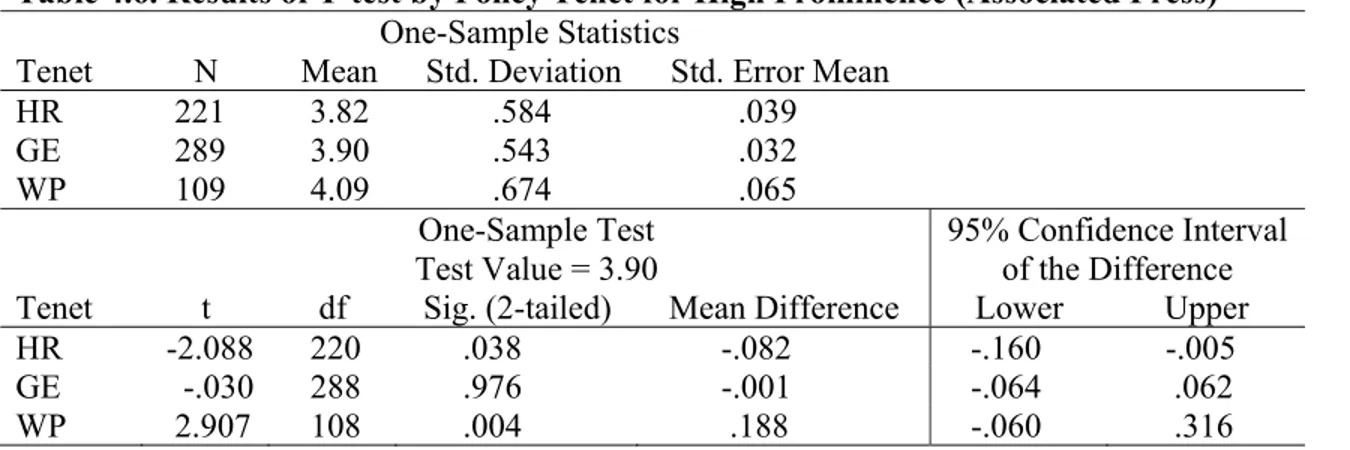

Table 4.6 Results of T-test by Policy Tenet for High Prominence (Assoc. Press) 136

Table 4.7 Results of Independent Binomial Test (Tenet by Prom., Assoc. Press) 136

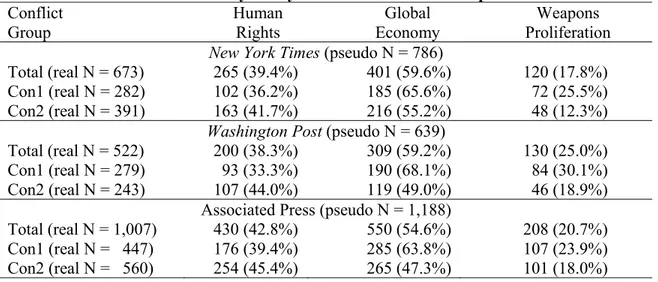

Table 4.8 Article Distribution by Policy Tenet and Conflict Group 138

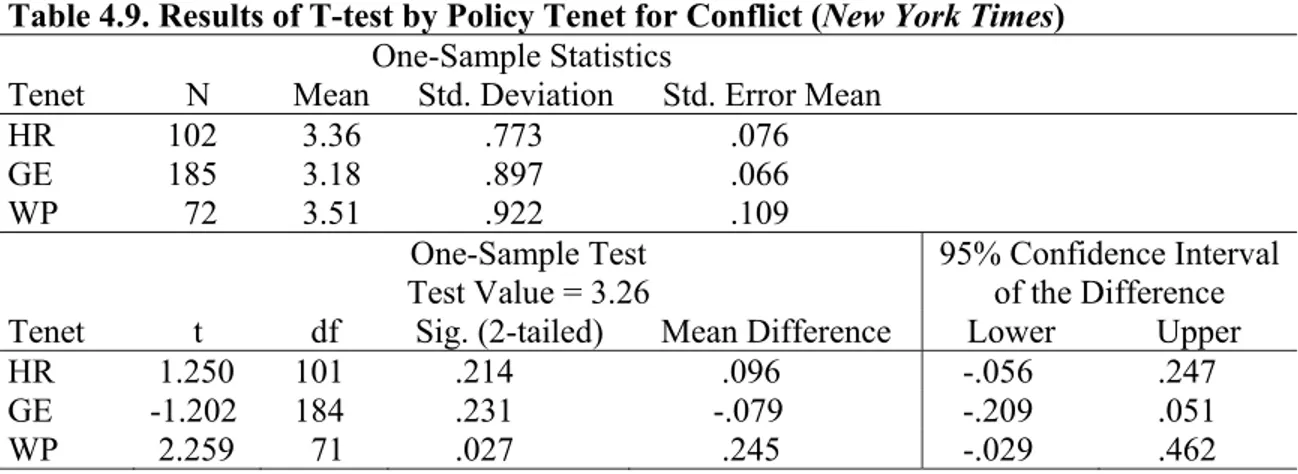

Table 4.9 Results of T-test by Policy Tenet for Conflict (NY Times) 139

Table 4.10 Results of Independent Binomial Test (Tenet by Conflict, NY Times) 139

Table 4.11 Results of T-test by Policy Tenet for Conflict (Wash. Post) 141

Table 4.12 Results of Independent Binomial Test (Tenet by Conflict, Wash. Post) 142

Table 4.13 Results of T-test by Policy Tenet for Conflict (Assoc. Press) 142

Table 4.14 Results of Independent Binomial Test (Tenet by Conflict, Assoc. Press) 143

Table 4.15 Results of T-test by Conflict (NY Times) 145

Table 4.16 Results of Independent Binomial Test (Organization by Conflict) 146

Table 4.17 Results of T-test by Conflict (Wash. Post) 147

Table 4.18 Results of T-test by Conflict (Assoc. Press) 147

Table 4.19 Results of Simple Regression by Organization 152

Table 4.20 Results of Simple Regression by Conflict and by Prominence 154

1

Introduction

In an attempt “to identify the major variations that have developed in Western democracies in the structure and political role of the news media” (2004, 1), Hallin and Mancini argued that the liberal model of mass media embodies an appropriate description of a system through which political news reporting is conducted where commercial media are dominant and noncommercial media are marginalized, state intervention in the daily affairs of news organizations is limited, official linkages between news organizations and political institutions are weak, and the adherence to specific standards of journalistic professionalism is an assumed occupational necessity for news reporters (2004, 198-199). In explaining the variation among these characteristics within the media systems of several North Atlantic countries, they conceded that the characteristics were applicable to each country in unique ways and in varying degrees. Moreover, the United States media system was argued to be the “purer example of a liberal system” (Hallin and Mancini 2004, 198). Thus, when interpreted alongside the notion that the liberal model and its characteristics are “commonly taken around the world as the normative ideal” (2004, 247), it is perhaps understandable why the United States, as the perceived icon of this ideal, has been a case frequently employed in academic research aiming to describe and explain the processes, determinants, and effects of political news reporting.

Given that the liberal model was argued (lamentably) by Hallin and Mancini to be “the wave of the future in the sense that most media systems are moving in important ways in its direction” (2004, 247-248), it also seems likely that investigations of yet underexplored aspects (both attractive and unattractive) of the United States media system will continue to be relevant. The current study undertook an investigation of an aspect considered unattractive by Hallin and Mancini: the supposed “lack of diversity” (2004, 247) resulting from the United States media system’s applicability to the liberal model. Specifically, this study asked whether the political institutional approach to news media systems, which presumes that such lack of diversity carries with it a degree of media power, is as applicable for international news reporting as it is considered to be for domestic political news reporting at the national level.

Most research on the United States media system preceding the political institutional approach was conducted as part of the mass communication perspective of the field of political communication, a perspective that Bell, Conners, and Sheckels have argued focuses

2

on “the role of the mass media with regard to politics, its relationship with politics, and the potential influence media may have in … political events” (2008, 58). Explanatory research adopting these three foci have historically yielded two types of findings centered on the actual content of political news (with little reference to an actual system containing this content): one regarding content antecedents (specific factors assumed to affect the content of news); the other regarding content effects (specific actions assumed caused by or correlated with the content of news). In contrast to research on the various media systems in Western Europe, many studies investigating political news as part of the United States media system have historically been preoccupied with determining how news content affects political processes and outcomes. As Blumler has argued, the European perspective was that American researchers “had marched up a blind alley out of which there was no clearly signposted exit” (1982, 146).

Research on both effects and antecedents benefitted from an escalation of scientific investigation of political communication in the latter half of the twentieth century (Shoemaker and Reese 1996, 5). However, regarding their respective contributions to the development of communication theory, Shoemaker and Reese argued that “content studies … have provided substantially more data than theory … compared with the studies conducted on the ‘effects’ side” (1996, 5). In explaining this phenomenon, Shoemaker and Reese argued that “the common threads among” content studies “have largely been ignored, and the growth of theory inhibited” (1996, 6). In a later explanation, Reese and Ballinger (2001) argued that the lack of theory on the production of news content resulted from news gatekeepers being interpreted by initial American scholars as mere representatives of American culture, acting in the public’s interest in their selection of content for audiences to consume. Tongue-in-cheek, Reese and Ballinger explained that gatekeepers were “like the filters audiences erect against ungratifying content, rendering the end product of news selection just as unproblematic as the viewer’s choices” (2001, 653).

This initial interpretation of gatekeepers as individuals, when compared to the ideological and institutional interpretations of gatekeepers dominant in European media studies (Reese and Ballinger 2001, 641), also made gatekeepers and the consequences of their work less interesting as research subjects (Reese 2008, 2985). Regarding political news reporting, this lack of interest contributed to the landscape by which conclusions about the antecedents and effects of news content were drawn in near isolation from one another with little evidence suggesting that they might be intertwined in a more comprehensive model of newsgathering, reporting, and political activity (i.e., that news making was part and parcel of the American

3

political culture). It was not until gatekeepers became more commonly interpreted as systematically working against the public’s interest that research on the antecedents of news content regained the interest of American scholars (Reese 2008, 2985), and the seeds of various comprehensive models were subsequently planted.

Among the first to argue the necessity of a new integrative research tradition were Shoemaker and Reese, who explained in a general sense that “given that most theories used in mass communication studies are derived from other disciplines … the emphasis often is … not on the processes through which media content is first formed and then affects people and society” (1996, 247). In response, they proposed that “linking influences on content with the effects of content can help build theory and improve our understanding of the mass communication process” (1996, 243). They outlined a specific research design through which the production of media content and its effects might be integrated by looking “at both how characteristics of the media environment operate as contingent conditions for the relationship between content’s characteristics and its effects, and how the audience’s use of content intervenes in the same relationship” (1996, 246).

The aims of Shoemaker and Reese’s design closely resemble those of political communication researchers in the United States interpreting, and scientifically testing the interpretation of, the news media as a political institution. This approach makes the assumption that a homogeneous news reporting environment characterized by newsgathering norms and routines standardized across various news organizations yields stronger content effects than an environment where antecedents are not homogeneous. However, in a minor deviation from Shoemaker and Reese’s design, rather than the audience’s usage of content acting as an intervening factor, the institutional approach holds that the adherence of news content to the expectations of other political institutions (which grant journalists and news organizations political legitimacy) intervenes in the relationship between the characteristics and effects of news content. Furthermore, as an “immediate concern for journalists” (Ryfe 2006, 138), political legitimacy feeds back to news content as an antecedent; as Ryfe has argued, “In their search for political legitimacy, journalists find themselves in a complicated, uneasy relationship with public officials, and, more broadly, the political culture. It is this relationship that news routines and practices are intended to mediate” (2006, 139).

By incorporating this political legitimacy effect of political news content as a feedback content antecedent, the political institutional approach considers both antecedents and effects as necessary components of a more comprehensive, coherent, and contextual framework than frameworks offered by prior political news researchers. Moreover, while the substance of the

4

institutional framework is political, the process it describes is cultural in that the very legitimacy afforded to journalists by the political actors about whom they report is argued to contribute to how policy gets made in the United States: “Newsmaking and policymaking are increasingly intertwined to the point of being indistinguishable. Thus, what we see as an effort to make news may be understood by an official as an effort to shape policy” (Cook 2006, 167). In this way, the strength of the approach is its reconciliation of conceptualizations of the news media as both “disseminators and determinants of political … power” (Lawrence 2006, 226), which prior theoretical frameworks could only interpret as contradictory. Furthermore, as Ryfe has noted, “By linking the study of news routines and practices to new institutionalist theory, [core scholars, Cook (2005) and Sparrow (1999)] have captured the essence of what scholars have learned about the news media over the last three decades. Moreover, this linkage has opened the way to promising new directions for research” (2006, 136).

However, while its comprehensiveness is the institutional approach’s virtue, its necessary expansiveness is its vice as some elements of its framework have yet to be resolved. For example, Lawrence has shown that the very definition of the term institution has not yet been appropriately standardized within the literature, as some scholars use the term to denote an

institutional environment of news organizations, while others use the term to denote an

institutionalized practice of news production employed by these organizations (2006, 227). As shown in Section 1.1 of the current study, scholars of the theory of new institutionalism such as DiMaggio and Powell (1991) and Goodin (1996) consider both concepts as crucial elements of any study of institutions and organizations. For this reason, and to help prevent similar conflations in future studies of the news media as a political institution, except when necessarily referencing previous institutional research, this study uses the under-defined noun

institution as seldom as possible. Instead, the more specific adjective forms institutional and

institutionalized provided in Lawrence’s examples are used. In addition, obvious terminological and conceptual ambiguities within the literature are identified and explained whenever necessary.

One area in which research results yielded from inquiries taken from an institutional approach are not yet adequate is regarding the distinction between news reporting about political issues domestically and internationally. More than just a lack of distinction, the institutional approach has almost exclusively been used to explain the process of United States news reporting of domestic affairs, while news reports focusing on international affairs and United States relations with and policies toward other countries, conceptualized here as

5

international news, have received little scholarly attention. (The few extant studies known by this author are reviewed in Section 2.1.3) That this distinction has not been made is odd considering that international news is explicitly categorized as international or foreign by the few United States news organizations that maintain bureaus outside the United States, considering that conclusions drawn from research on international news in the fields of political communication and mass communication have historically been held by scholars as distinct from those drawn from research on domestic news, and considering that these conclusions have typically been critical of a lack of diversity in international reporting by United States news organizations.

The current study sought to fill this research gap by explicitly applying (and testing this applicability) to an international context the theoretical framework outlined by core scholars considering the news media as a political institution. This framework depends on three defining assumptions. First, the political legitimacy and economic interests of modern news organizations act as both competing and complementary antecedents (i.e., constraints) that determine the content of political news. Second, as different United States news organizations all operate in the same institutional environment, their competition with each other and their historical standardization of these content antecedents into journalistic norms and routines contribute to the similarity of their news products. Third, the usage of news organizations and their news products by political actors as means of intragovernmental communication contributes to the increasing intertwining of news making and policy making.

This framework, in addition to following Shoemaker and Reese’s proposal for incorporating content antecedents and effects into a single model, was derived from the application of the theory of new institutionalism to the field of organizational analysis. As such, the outlining of this theory’s application to the political news reporting industry provided in Section 1.2 follows an initial discussion of how new institutionalist concepts were adopted by scholars of organizational analysis in Section 1.1. As explained in Section 1.2.3, new institutionalism has been utilized by political communication scholars since the late 1990s as a tool for explaining the one element of the framework that a previous movement of studies from the organizational approach in the 1970s were unable to explain: that “despite considerable variation in audiences and formats, the news is similar from one news outlet to the next” (Cook 2006, 161).

In Chapter 4, this assumption made by scholars interpreting the news media as a political institution is tested empirically and statistically in an international context carefully selected so that the differences between newsgathering routines regarding domestic and international

6

affairs could be minimized. As the institutional framework emphasizes the practice of routine reporting, so called by virtue of its stability and consistency over long periods of time, it was necessary to incorporate a case that was broad enough and protracted enough to ensure that relevant news articles reported regularly over a period of several years would be available for analysis. Details regarding the international context used and the related United States foreign policy that comprised the content of the news and the political activity statistically analyzed are introduced in Section 2.1.4 and explained more fully throughout Chapter 3. Assuming that at least some elements of news content would be found to be similar across different news organizations, a research design closely adhering to the theoretical framework outlined by scholars of the news media as a political institution was employed to test the framework’s main points of argument regarding the content’s antecedents and effects. This research design is also described in detail throughout Chapter 3.

The current study is believed by the present author to be the most thorough analysis yet of the new institutional approach in an international context. In an effort to provide evidence for this claim, separate examinations of the theoretical contributions and methodologies of previous studies on international news are conducted in Chapter 2. The examination of theoretical contributions exposed the comparative lack of theory guiding studies of international news, which the current study argues could only be properly addressed by incorporating specific guidelines into this study’s methodology. As such, the examination of previous studies from a methodological standpoint provided a landscape for assessing whether studies have incorporated these guidelines. The purpose for conducting separate theoretical and methodological reviews was to illustrate that the research design employed by this study was in direct response to the methodological deficiencies of previous research. Specifically addressed is the overemphasis on influence between news reporters and policy

makers, insufficient conceptualizations of the term the media, and insufficient

operationalizations of news prominence.

Chapter 5 offers some conclusions that can be drawn based on the results of the analyses conducted in Chapter 4. It is concluded that while the institutional approach as a whole is not applicable to the international context employed in this study, some aspects of the framework (e.g., those related to normative journalistic constraints and the concept of government by publicity) are individually applicable. More specifically, while the current framework based on domestic news reporting suggests that homogeneity among news organizations also explains the political functionality of their coverage as a means of intragovernmental communication, the international context considered here revealed that this function of news

7

coverage was better explained by how prominently coverage was portrayed. Thus, as the prominence of coverage is a decision made at the organizational level, some combination of elements from the organizational and institutional approaches may yield the most applicable model of international news production. If a logical induction can be made from the international context considered here, such a model would emphasize the political (rather than economic) constraints on coverage employed by organizations in addition to their choices regarding how prominently a given aspect of an issue and/or a foreign policy is covered.

The present author acknowledges that the conclusions drawn in this study that diverge from institutionalism may also be the product of a certain tension resultant from pairing the theoretical assessments of the institutional approach with mostly quantitative methods of data collection and analysis. Indeed, that the current study’s concern with measuring the prominence of coverage would lead to some conclusions in favor of a more organizational approach is not surprising given that the institutional approach (like research linking international news with foreign policy making) has not incorporated specific conceptualizations of news prominence into its theoretical framework. To be sure, discussions of what news makers consider newsworthy abound; however, operationalizing the evidence of this newsworthiness has entered less into the discussion. In this regard, a useful tool for navigating the resultant tension was Riffe, Lacy, and Fico’s centrality model of communication content (2005, 12), which was designed specifically to facilitate the usage of largely quantitative methods of content analysis to answer research questions related to Shoemaker and Reese’s proposal for integrating the antecedents and effects of communication content.

Noting that their conceptualization of the centrality of content between its antecedents and its effects “does not reflect accurately the state of communication research in terms of studies of content production or effects” (2005, 12), Riffe, Lacy, and Fico hoped that their model would illustrate “why content analysis can be an important tool in theory building about both communication effects and processes” (2005, 11). Following this line of thinking, the current study hopes to contribute to theory building regarding the news media as a political institution through its method of content analysis in addition to its employment of an international context as a case. Specifically, it seemed reasonable to this author that somewhere within the increasing indistinguishableness of news making and policy making is a place for the actual visibility of news content. For this reason, the prominence of news was carefully operationalized to the point where this evidence of the so-called newsworthiness of

8

the content of one news article could be assessed against another. In this way, the results of this study’s analyses may be explainable in terms of the methodology employed or from the fact that an international context was employed as a case. Future studies employing either a similar methodology on a different international context or a more qualitative methodology on the same context will be necessary to make clear distinctions between these two possibilities.

9

Chapter 1

United States News Media as a Political Institution

This chapter establishes the current state of two fields of literature from which this study proceeded. Section 1.1 outlines the main components and explanatory contributions of the theory of new institutionalism, focusing on how it has been interpreted by scholars of organizational analysis. According to the most commonly accepted of interpretations, the main impetus of a particular industry’s process of institutionalization (depending on the character and nature of that industry) may be regulatory, normative, and/or cultural-cognitive, and may emphasize some combination of professionalization, homogenization, and legitimization regarding routine occupational behaviors. Section 1.2 explicates how new institutionalism theory has been applied to the political news making industry to explain the process of domestic political news reporting in the United States at the national level (i.e., the consideration of the news media as a political institution). It is noted how institutional scholars of the news media have traced the historical trajectory of normative constraints related to the professionalization, homogenization, and legitimization of journalistic behaviors in their coverage of political affairs in order to provide evidence for the argument that the news media comprise a political institution.

1.1 New Institutionalism Theory

Following Meyer, Boli, and Thomas (1987), Scott noted, “In the modern world, commencing with social processes associated with the Enlightenment, three categories of actors have been accorded primacy: individuals, organizations, and societies …” (2008, 74-75). In American mass communication research, an emphasis on individual level inquiries has stifled the interpretation of systematic news gatekeeping as a socially relevant object of inquiry, subsequently delaying the integration of studies on the effects of news content with studies on news antecedents (Reese 2008, 2985). For scholars of the theory of new institutionalism, this emphasis on individualism was not unique to research on mass communication, but rather was a symptom of the overall ontology of the American social science tradition: “Modern culture depicts society as made up of ‘actors’ … together with the organizations derived from them. Much social science takes this depiction at face value, and

10

takes for granted that analysis must start with these actors and their perspectives and actions” (Meyer and Jepperson 2000, 100). This ontological critique developed as “a reaction against the behavioral revolution … which interpreted collective … behavior as the aggregate consequence of individual choice” (DiMaggio and Powell 1991, 2). Indeed, some early proponents of this critique asserted that “what we observe in the world is inconsistent with the ways in which contemporary theories ask us to talk” (March and Olsen 1984, 747).

Instead of relying on so-called actorhood, scholars of new institutionalism have

contended that collective social phenomena might be better explained by “seeing actors (and interests and structures and activity) as … derivative from institutions and culture” (Jepperson 2001, 3). As Jepperson argued, “People and activity are … thoroughly invoked in institutionalist arguments. But the people who are invoked are not usually actors, and the activity invoked is not usually action …. Instead the people invoked in this institutionalism are usually operating as agents of the collectivity (like professionals or state elites or advocates), formulating or carrying broad collective projects” (2001, 27). Due to the malleability of its interpretation of collective action as more than merely the sum of individual actions, new institutionalism has been adopted by “each of the several disciplines that collectively constitute the social sciences …” (Goodin 1996, 2). Based on the notion that each discipline originally “contained an older institutionalist tradition” (1996, 2), Goodin systematically traced the method by which new institutionalism was “resurrected” by scholars of history, sociology, economics, political science, and social theory, observing that “new institutionalism mean[s] something rather different in each of these alternative disciplinary settings” (1996, 2). Similarly, DiMaggio and Powell argued that the various new institutionalisms were “united by little but a common skepticism toward atomistic accounts of social processes and a common conviction that institutional arrangements and social processes matter” (1991, 3).

Nevertheless, as Goodin explained, “all those variations on new institutionalist themes are essentially, and importantly, complementary” (1996, 19). As such, some theoretical strands emergent in the new institutionalist literature can be best articulated by highlighting the disciplinary boundaries they straddle. For instance, while the term agents in Jepperson’s assertion above is a reference to people who have been socialized or institutionalized in how they go about their (work related) actions, one application of new institutionalism found in studies of both sociology and political science has focused instead on the organizations within which these actions might take place. New institutionalist themes in this field of so-called organizational analysis, which eclectically “takes as a starting point the striking

11

homogeneity of practices and arrangements found in the labor market, in schools, states, and corporations” (DiMaggio and Powell 1991, 9), have been adopted by scholars sensing an overemphasis on locality and actor uniqueness in their respective fields. Indeed, as explained later in Section 1.2, it is this very starting point upon which the theoretical framework employed by scholars of the news media as a political institution relies.

In order to set up a description of this framework, Sections 1.1.1 through 1.1.3 establish what has emerged as a common set of tools for use in applying new institutionalism to the analysis of an organizational field, which DiMaggio and Powell have defined as “those organizations that, in the aggregate, constitute a recognized area of institutional life: key suppliers, resource and product consumers, regulatory agencies, and other organizations that produce similar services or products” (1991, 64-65). In this regard, Scott’s “omnibus conception of institutions” provides an auspicious preface to introducing these tools: “Institutions are comprised of regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive elements that, together with associated activities and resources, provide stability and meaning to social life” (2008, 48). Following Hoffman (1997, 36), Scott argued that these “three elements form a continuum moving ‘from the conscious to the unconscious, from the legally enforced to the taken for granted’” (2008, 50).

It is shown below that in the field of organizational analysis the old sociological and political science institutionalisms, which respectively emphasized cultural-cognitive and regulative elements in their explanations of collective behavior, have converged in their new institutional variants toward more normative explanations (without fully abandoning their respective origins). Specifically, Section 1.1.1 outlines the shift in the sociological variant of institutionalism from a focus on unconscious toward more conscious explanations of organizational compliance. It is shown that this shift corresponded with a stronger emphasis placed on the dual capacities and dual constraints of organizations as institutional intermediaries. Section 1.1.2 outlines the shift in the political science variant of institutionalism from legally enforced toward more cooperative explanations of organizational compliance. It is shown that this shift corresponds with a change in focus from vertical interactions between organizations and institutions to organizations’ horizontal interactions. Section 1.1.3 discusses how the conformity of organizations to an institution’s regulative, normative, and/or cultural-cognitive elements has been argued by scholars of organizational analysis to increase their perceived legitimacy in different ways. Special attention is given to normative mechanisms of legitimacy, especially those related to the

12

professionalization of an occupation, as it is considered the source of organizational homogenization by scholars that view the news media as a political institution.

1.1.1 Sociological Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis

In Goodin’s (1996) retracing of the development of new institutionalism within the disciplines of social science, a “key-variable” was assigned to each discipline to emphasize that discipline’s contribution to the institutional approach. Goodin offered that “the one owned by sociology might be … ‘the collective.’ … It is the hallmark of sociological institutionalism … to emphasize how individual behavior is shaped by (as well, perhaps, as shaping) the larger group setting” (1996, 7). This concept of the collective, which was echoed by Jepperson’s (1991) concept of the collectivity, also succinctly describes sociological institutionalism’s influence on the field of organizational analysis. Even if the term were meant only to imply superficially the existence of a group of actors doing similar things, evidence of this influence would be found in DiMaggio and Powell’s definition of an organizational field. However, Goodin (following Granovetter (1985) and Granovetter (1992)) argued that the term carries a deeper implication that actions taken by individual actors “are shaped … by the institutional contexts in which they are set” (1996, 6), which immediately sets as a criterion for group membership the foregoing of at least some capacity for individual decision making. In this sense, in addition to (and regardless of) any interaction between individual members, the collective implies the existence of at least one (top-down) direction of socializing interaction between member and group: namely, the (intentional or unintentional) submission of individual actors to the collective’s institutional context.

It is this focus on the institutional context rather than on the collective itself that separates new sociological institutionalism from its earlier and “older” counterpart. As Goodin argued, “The old institutionalism within sociology focused upon ways in which collective entities … create and constitute institutions which shape individuals, in turn” (1996, 7). In this older tradition, the dominant institutionalizing force was, in DiMaggio and Powell’s terms, mimetic

in that types of behavior other than compliance were “inconceivable; routines are followed because they are taken for granted as ‘the way we do things’” (Scott 2008, 58). Thus, the unit of analysis focused on by old institutionalists was the institution itself; as Goodin has noted, “Observing structures, [old institutionalists] tended simply to assume that they made some functional contribution to social stability … approving of the various ways in which the collective conscious got a grip on individuals” (1996, 5-6). Scott interpreted that this thoughtless compliance of institutionalized individuals was able to endure over time because

13

of the “cultural-cognitive elements of institutions: the shared conceptions that constitute the nature of social reality …” (2008, 57). Scott asserted that in this conception of institutions “‘internal’ interpretive processes are shaped by ‘external’ cultural frameworks” (2008, 57).

In contrast to the inability of actors to conceive of alternative actions implied by old institutionalists, Goodin argued that “new institutionalism focuses … upon ways in which being embedded in such collectivities alters individuals’ preferences and possibilities” (1996, 7). In this way, the compliance of individual actors is not interpreted as inevitable, but rather as obligatory. Scott described this shift in focus as one toward the normative elements of institutions: “… normative rules that introduce a prescriptive, evaluative, and obligatory dimension into social life” (2008, 54). It is these elements that define a given collective’s institutional context (in Goodin’s terminology), which within the field of organizational analysis is often referred to as an institutional environment. Listing examples of various organizational fields, DiMaggio and Powell described institutional environments as being “coterminous with the boundaries of industries, professions, or national societies” (1991, 13); in other words, they exist within a given organizational field. Furthermore, these “conceptions of the preferred or the desirable” (Scott 2008, 54) need not be standardized among organizations themselves. Instead, as DiMaggio and Powell have argued, environments are “subtle in their influence; rather than being co-opted by organizations, they penetrate the organization” (1991, 13). Through this penetration, they continued, echoing Goodin’s assessment of new institutionalism’s focus, environments create “the lenses through which actors view the world” (DiMaggio and Powell 1991, 13).

Nevertheless, organizations increase the complexity of the institutionalization process through their dual conceptualization as (in Jepperson’s (2001) terms) formulators and carriers (i.e., agents) of a given collectivity and as collectivities in and of themselves. Indeed, conceptualizing organizations as such has allowed scholars of organizational analysis to suggest another (bottom-up) direction of institutionalization extant between environments and agents. As explained by Goodin, “New sociological institutionalists of this [(organizational)] stripe point … to the important role that intermediate organizations can and do play in shaping and reshaping both individual actions and collective outcomes emanating from them” (1996, 6). DiMaggio and Powell argued similarly that organizations “do not merely reflect the preferences and power of the units constituting them; [they] shape those preferences and that power” (1991, 7). In this way, from a sociological standpoint, organizations are considered intermediaries of the organizational field whose practices are twofold as “either reflections of or responses to rules, beliefs, and conventions built into the

14

wider environment” (Powell 2007). This conceptualization reflects Gidden’s concept of a social structure, which is both “the medium and the outcome of the practices they recursively organize” (1984, 25).

Early organizational analysis studies recognized the apparent inconsistency of this duality, especially in light of the field’s development as a response to the perceived inadequacy of rational-choice models in explaining individual behavior within an institutional environment. As March and Olsen conceded in their discussion of the United States political environment, “Ideas based on the assumption that large institutional structures (e.g., organizations, legislatures, states) can be portrayed as rationally coherent autonomous actors are uneasy companions for ideas suggesting that political action is inadequately described in terms of rationality and choice” (1984, 738). Nevertheless, March and Olsen’s position on this matter was clear: “Without denying the importance of both the social context of politics and the motives of individual actors, the new institutionalism insists on a more autonomous role for political institutions” (1984, 738). Following Nordlinger (1981), they offered that “the state is not only affected by society but also affects it” (March and Olsen 1984, 738). Citing examples from each official branch of United States government, they continued, “The bureaucratic agency, the legislative committee, and the appellate court are arenas for contending social forces, but they are also collections of standard operating procedures and structures that define and defend interests. They are political actors in their own right” (March and Olsen 1984, 738).

March and Olsen maintained that these dual capacities of organizations, characterized by their seemingly inconsistent conceptualizations and practices, need not be contradictory: “The argument that institutions can be treated as political actors is a claim of institutional coherence and autonomy” (1984, 738). However, arguing these claims involved a reinterpretation of organizations’ capacities as dual constraints. Thus, while Goodin noted that according to the new institutionalism of political science “individuals are shaped by, and in their collective enterprises act through, structures and organizations and institutions,” (1996, 13), March and Olsen added that “the claim of coherence is necessary in order to treat institutions as decision makers” (1984, 738), which implied that organizations make choices “on the basis of some collective interest or intention (e.g., preferences, goals, purposes)” (March and Olsen 1984, 739). Likewise, they argued that “the claim of autonomy is necessary to establish that political institutions are more than mirrors of social forces” (March and Olsen 1984, 739). In this way, suggesting that organizations (in their terms, political institutions) are autonomous implied that their choices based on so-called collective interest

15

might be consciously made: “These constraints are not imposed full-blown by an external social system; they develop within the context of political institutions” (March and Olsen 1984, 740).

1.1.2 Political Science Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis

Arguing that “old institutionalists might have been insufficiently sensitive to [the institutional] constraints” (1996, 13) discussed by March and Olsen, Goodin noted that March and Olsen’s reinterpretation of organizational capacity was one indication of a “new” focus of institutionalist scholars within political science. Following Nordlinger (1981), and echoing March and Olsen’s line of thinking, Goodin argued that political organizations “are constrained both in their ‘relative autonomy’ and in their ‘power to command’ (i.e., to implement their decisions)” (1996, 13). Nevertheless, March and Olsen’s argument shared an important feature with the old political science institutionalist way of thought: namely, that the dominant institutionalizing force was, in DiMaggio and Powell’s terms, coercive in that “formal and informal pressures [are] exerted on organizations by other organizations upon which they are dependent” (1991, 67). As such, these scholars focused only on the vertical interactions occurring between organizations and institutions, which Scott has interpreted as institutions’ regulatory processes and defined as “the capacity to establish rules, inspect others’ conformity to them, and … manipulate sanctions … in an attempt to influence future behavior” (2008, 52). Offering the United States Congress as an example, DiMaggio and Powell cited that “legislative rules are seen as robust, resistant in the short run to political pressures, and in the long run, systematically constraining the options decision makers are free to pursue” (1991, 6).

However, other new political science institutionalist scholars have focused on how organizational choices are shaped through their horizontal interaction with other organizations; as Powell has argued, “organizations operate amidst both competitive and cooperative exchanges with other organizations” (2007). Whether these inter-organizational exchanges are competitive and/or cooperative by design is a point of scholarly division within the new political science institutionalism. On one hand, the so-called positive theory of institutions, whose scholars have typically focused on the formation and duration of political institutions within a single country, has followed the tradition of emphasizing regulatory processes and exchanges by design. In this regard, political institutions are considered “ex ante agreements” that “economize on transaction costs, reduce opportunism and other forms of agency ‘slippage,’ and thereby enhance the prospects of gains through

16

cooperation” (Shepsle 1986, 74). It is this positive perspective that Goodin referred to when selecting the key variable power to succinctly describe political science’s contribution to new institutionalism. After all, Goodin argued, “The capacity for one person or group to control the actions and choices of others – or, better yet, to secure its desired outcomes without regard to anyone else’s actions or choices – is what politics is all about” (1996, 15-16). DiMaggio and Powell similarly described the horizontal analyses of positive theory scholars as examinations of “the efforts of one political actor (e.g., a congressional subcommittee) to control another (e.g., a federal agency)” (1991, 6).

On the other hand, as DiMaggio and Powell have noted, “Missing from the positive theory’s models of rules and procedures are the dynamic, informal features of institutions” (1991, 6), which have been emphasized mostly by scholars focusing on the formation and duration of international regimes. Following Krasner (1983), Keohane (1984), Keohane (1988), and Young (1986), DiMaggio and Powell argued that scholars in this tradition “have explored the conditions under which international cooperation occurs, and examined the institutions (regimes) that promote cooperation” (1991, 6). Listing several examples, DiMaggio and Powell stated that “some of these international institutions (e.g., the United Nations or the World Bank) are formal organizations; others, such as the international regime for money and trade (GATT or General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs) are complex sets of rules, standards, and agencies” (1991, 6-7). In either case, they continued, “Regimes are institutions in that they build upon, homogenize, and reproduce standard expectations and, in so doing, stabilize the international order” (DiMaggio and Powell 1991, 7). As with the institutions described by positive theorists, this order is achieved (even in competitive environments) through the ultimate cooperation of individual organizations. However, what distinguishes scholars of international regimes is their acceptance that neither the nature of this cooperation nor the character of the institutional environment itself need be “products of conscious design” (DiMaggio and Powell 1991, 8).

As DiMaggio and Powell argued, this “rejection of intentionality is founded on an alternative theory of individual action, which stresses the unreflective, routine, taken-for-granted nature of most human behavior and views interests and actors as themselves constituted by institutions” (1991, 14). As such, this perspective is reflective of the normative system focused on in studies of new sociological institutionalism. As Scott argued, explaining the attractiveness of normative explanations to political science institutionalists, “Normative systems are typically viewed as imposing constraints on social behavior …. But, at the same time, they empower and enable social action. They confer rights as well as responsibilities;

17

privileges as well as duties; licenses as well as mandates” (2008, 55). Normative systems reconcile these dualities through the existence of norms, which “specify how things should be done [and] define legitimate means to pursued valued ends” (Scott 2008, 54-55). Thus, as Scott argued, “Theorists embracing a normative conception of institutions emphasize the stabilizing influence of social beliefs and norms that are both internalized and imposed by others” (2008, 56).

Normative explanations of organizational behavior have also been incorporated by scholars of domestic politics attempting to explain more than the positive theory allows. For example, in a study of the United States National Labor Relations Board, Moe criticized the analytical limitations of positive theorists: “Perspectives on control that rivet attention on the conscious, intentional efforts of one actor to control another tend to misconstrue the essence of the problem. In politics, control is often indirect, unintentional, and systemic” (1987, 291). Moe continued, “In the absence of an institutional theory that fully recognizes these dynamics, we are guided by models that highlight the more fixed and formal aspects of political structure – whether or not these are central or even of much relevance to an explanation” (1987, 294). To expand their explanatory capacity, Moe recommended that positive theorists attempt to incorporate into their theories “the informal rules and norms” of institutional environments that “generally emerge over time through the adaptive adjustments of many participants” (1987, 294).

Incidentally, while Moe’s suggestion was mainly directed toward scholars of institutional environments that developed at least partially because of formalized rules of engagement, the analytical standpoint itself has lent itself particularly well to studies of environments not preceded by such regulative elements. Namely, a stream of organizational analysis has arisen focusing on entire industries that, although comprised of various independent and autonomous organizations, have learned to function coherently through organizational cooperation. As DiMaggio and Powell argued, “The successful application of institutional models to the adoption of structural elements and practices by proprietary companies … has become a growth industry” (1991, 32). For example, in a longitudinal analysis of the United States chemical industry, Hoffman (following Brint and Karabel (1991) and White (1992)) first presented “a view of organizational fields as ‘arenas of power relations’ wherein field-level constituents engage in institutional war” (1999, 367). However, rather than one constituent controlling another as suggested by positive theorists, Hoffman argued (following Selznick (1949)), “The outcome of this war is the product of a political negotiation process in which politics, agency relationships, and vested interests guide the formation of institutions

18

that will guide organizational behavior” (Hoffman 1999, 367). The resulting “fieldwide cooperation” (Hoffman 1999, 359) suggests that while regulative power may have been political science’s contribution to new institutionalism as a whole, voluntary cooperation was the discipline’s more particular contribution to organizational analysis.

1.1.3 Legitimacy and Homogeneity in Organizational Analysis

As shown in Hoffman’s longitudinal analysis, homogeneity within an organizational field can take time to develop and might progress over a number of stages. DiMaggio and Powell have explained this phenomenon: “In the initial stages of their life cycle, organizational fields display considerable diversity in approach and form. Once a field becomes well established, however, there is an inexorable push toward homogenization” (1991, 64). Scholars of the news media have similarly attempted to historically trace the process by which major news organizations in the United States converged in how they report political news. However, in contrast to Hoffman’s analysis, which attributed homogenization among chemical companies to similar responses by each organization to a particular environmental issue, media scholars saw convergence in styles of reporting political news as having been instigated by technological advances and market forces that necessitated increasingly professionalized and standardized news making practices. However, despite their differences, both explanations involved a new stimulus being introduced to an existing group of organizations, which subsequently sought legitimacy through their responses to the stimulus. To the extent that these responses were similar and the legitimacy being sought was from the same source, the result was the birth of an institutional environment.

Through this argumentation, legitimacy itself has been interpreted by scholars of organizational analysis as a homogenizing force. However, depending on a given institutional environment’s composition of regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive institutionalizing elements, legitimacy can be pursued and granted in various ways; as Scott has argued, “… legitimacy varies by which elements of institutions are privileged as well as which audiences or authorities are consulted” (2008, 62). For example, in a vertical sense, “The regulatory emphasis is on conformity to rules: Legitimate organizations are those established by and operating in accordance with relevant legal or quasilegal requirements” (Scott 2008, 61). Scott continued, “A normative conception stresses a deeper, moral base assessing legitimacy. Normative controls are much more likely to be internalized than are regulative controls, and the incentives for conformity are hence likely to include intrinsic as well as extrinsic rewards” (2008, 61). As DiMaggio and Powell (following Carroll and Delacroix (1982)) have noted,

19

normative legitimacy is also competed for horizontally among organizations (1991, 66). Finally, in explaining the “deepest” level of legitimacy, Scott argued, “A cultural-cognitive view points to the legitimacy that comes from conforming to a common definition of the situation” (2008, 61). In this regard, DiMaggio and Powell have argued, “Organizations tend to model themselves after similar organizations in their field that they perceive to be more legitimate or successful” (1991, 70).

Scott has argued, “The bases of legitimacy associated with the three elements are decidedly different and may, sometimes, be in conflict” (2008, 61). As such, “… it is not possible to associate any [discipline] uniquely with any of these proposed models” (2008, 70). As the name of their research field implies, in making the argument that the pursuit of legitimacy leads to homogeneity, scholars of organizational analysis offer an institutional explanation that focuses on the incentives of organizations to act rather than the structural composition of the institutional environment or the human psychology of their employees. Thus, explanations for homogeneous organizational fields provided by these scholars (much like the historical trends of the sociological and political science new institutionalisms) have tended to be based on normative rather than regulatory or cultural-cognitive elements. As DiMaggio and Powell have argued, “Organizations are rewarded for their similarity to other organizations in their fields. This similarity can make it easier for organizations to transact with other organizations, to attract career-minded staff, [and] to be acknowledged as legitimate and reputable” (1991, 73). Indeed, although regulative and cultural-cognitive explanations have not been ignored, by focusing on the professionalization and standardization of the news making industry as the main impetuses of organizational homogenization, scholars of the news media as a political institution have also relied on normative explanations.

While the professionalization of political news reporting is discussed throughout Section 1.2, DiMaggio and Powell (following Larson (1977) and Collins (1979)) have defined professionalization in general as “the collective struggle of members of an occupation to define the conditions and methods of their work … and to establish a cognitive base and legitimation for their occupational autonomy” (1991, 70). In contrast to the vertical cultural-cognitive elements of an institution, the cognitive base for this concept of autonomy is obtained and internalized by members a profession whose organizations interact horizontally. Likewise, even in systems where legitimacy is granted from outside the organizational field through interactions between organizations and the legitimating authority, the autonomy of the profession is dependent on the horizontal perception of this legitimation. Thus, echoing

20

the notion of institutional environments penetrating organizations, DiMaggio and Powell argued, “While various kinds of professionals within an organization may differ from one another, they exhibit much similarity to their professional counterparts in other organizations” (1991, 71). As argued by Scott (2008, 100), this phenomenon is the product of normative frameworks extant within institutional environments: namely, occupational standards to which professionals are obliged to adhere.

Naturally, the current argumentation for how professional legitimacy is obtained by organizations is not applicable to all types of proprietary-based industries. However, in industries where the conditions and methods of work are defined by normative standards, organizations are said to homogenize through their competitive adherence to these standards. As such, the most adeptly compliant organizations are rewarded not only with legitimacy, but with status and prestige as well. As DiMaggio and Powell argued, “Organizational fields that include a large professionally trained labor force will be driven primarily by status competition. Organizational prestige and resources are key elements in attracting professionals. This process encourages homogenization as organizations seek to ensure that they can provide the same benefits and services as their competitors” (1991, 73-74). Meyer and Rowan came to a similar conclusion from a more mimetic standpoint: “Organizations are driven to incorporate the practices and procedures defined by prevailing rationalized concepts of organizational work …. Organizations that do so increase their legitimacy and their survival prospects” (1991, 41). The next section outlines how this process of professionalization, legitimization, and homogenization has been applied in studies of the United States political news reporting industry.

1.2 Institutional Interpretations of Political News Reporting

Referencing the game of chess, Lawrence has argued that “overall, the new institutional approach requires the ability to see the whole board in motion – the occasional diversity and heterogeneity of news content within overarching patterns of convergence and homogeneity; journalistic autonomy that is nevertheless situated in, constrained by, and indeed constituted by market, state, and culture; newsmaking that is at the same time policymaking and governing; … a blooming, buzzing board of interinstitutional competition-within-interdependence that shapes the daily production of news” (2006, 226). In the four parts of this intentionally broad-brushed description of the new institutional approach to news reporting, four avenues by which the approach draws from the general theory of new