Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:21

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Let Them Decide: Student Performance and

Self-Selection of Weights Distribution

Brian A. Vander Schee

To cite this article: Brian A. Vander Schee (2011) Let Them Decide: Student Performance and Self-Selection of Weights Distribution, Journal of Education for Business, 86:6, 352-356, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.540047

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.540047

Published online: 29 Aug 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 178

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.540047

Let Them Decide: Student Performance and

Self-Selection of Weights Distribution

Brian A. Vander Schee

Aurora University, Aurora, Illinois, USA

Previous researchers have focused on student sense of control, grading, and academic perfor-mance. However, the influence of letting students self-select the percentage weights for graded course components is not clear. In this research students selected the percentage weights dis-tribution for the graded components in the Capstone: Strategic Management course. Students were then surveyed to solicit their feedback. The results indicate that student sense of control and performance were positively influenced by self-selecting the weights distribution. More-over, the self-selection process itself may account for variance in performance more so than calculating final course grades using a particular weights distribution.

Keywords: assessment, business capstone, sense of control, student performance

Student concerns regarding course grading is ubiquitous in higher education. Faculty concerns regarding students’ will-ingness to exert the effort needed to achieve the grades they expect is also common. The disconnect is cause for frustra-tion on both sides, with students holding some power via student evaluations of teaching with the balance of power resting with faculty as they assign grades. Perhaps faculty should have all the power. However, if the ultimate goal is to enhance student performance, then the incongruence be-tween student and faculty expectations could be addressed by having students more involved in the grading process. This may be particularly true at the senior undergraduate level, where students likely have a more accurate sense of their academic ability. This research adds to the body of knowl-edge by examining the influence of student self-selection of weights distribution on student sense of control and perfor-mance.

Literature Review

The source for earning higher grades may rest within stu-dents to a greater extent than they realize. This is manifested in the idea that high academic self-concept serves as an

in-Correspondence should be addressed to Brian A. Vander Schee, Aurora University, Dunham School of Business, Dunham Hall, Room 232, 347 S. Gladstone Avenue, Aurora, IL 60506-4892, USA. E-mail: bvanders@ aurora.edu

ternal motivator to greater academic performance in business education (Rodriguez, 2009). In other words, students who believe they have the academic ability to be successful in a course are more apt to do well than those who lack such confidence. Their motivation is shaped to a certain degree by academic expectations (Saenz, Marcoulders, Junn, & Young, 1999). It is the combination of high academic self-concept and academic expectations that inevitably leads to higher academic performance.

More specifically, researchers use the terms approach

and avoidance to describe behavior in reaching goals,

such as those related to academic performance (Elliot & McGregor, 2001; Pintrich, 2000). Approach describes ob-taining or demonstrating competence whereas avoidance deals with steering clear of demonstrating incompetence (Elliot, 2005). Students with low academic self-concept are likely less motivated to reach an academic goal, such as earn-ing an A in a particular course, because they believe that they do not have the ability to achieve it.

Efforts to overcome this barrier are numerous, with the use of self- and peer grading in the college classroom as rather common (Haas, Haas, & Wotruba, 1998). Involving students in this way prepares them to some extent to take responsi-bility for their performance. In fact, self-selection of weights distribution may mitigate the inherent bias of those with low academic self-concept by affording them the opportunity to have more control in how they will be assessed.

Increasing self-awareness regarding an individual’s learn-ing and academic performance fosters an increase in a sense of personal purpose for learning (Pavlovich, Collins, & Jones,

STUDENT PERFORMANCE AND WEIGHTS DISTRIBUTION 353

2009). However, whether purposive learning or increased sense of control in learning translates into an increase in aca-demic performance is not readily clear. Students use various strategies to increase their academic performance, and thus sense of control still appears to be a discriminating factor influencing final grade outcomes.

As a result grading in general is often used to elicit a sense of control for students and to encourage them to be more involved in the course (Walvoord & Anderson, 1998). Assigning weight to a certain aspect of the course, such as participation, inevitably draws students’ attention to a partic-ular area because they perceive that they may be rewarded for their effort. However, research regarding the use of student self-selection of weights distribution on course components to increase academic performance is limited. At the same time, a concern in business education is that students focus on gaining points in a course rather than learning the ma-terial (Mainkar, 2008), although having students sometimes speak out just to be heard for credit rather than to engage in a critical discussion is likely better than complete silence in the classroom.

This apparent misguided motivation can be mitigated to some extent with student involvement in the grading scheme for the course as a way to emphasize participative learning (Mills-Jones, 1999). The basis for this supposition is that students may feel more accountability and sense of control for their performance if they have a part in the decision regarding how they will be evaluated. This may also help resolve student conflict associated with the desire to learn and the desire to get good grades (Horowitz, 2010).

Often students perceive that faculty place too much weight on examinations and papers and much less emphasis on a combination of other criteria (Spencer & Labenberg, 1997). A student may discover at the outset of a course that much of the grade is weighted toward areas that are perceived weaknesses. Perhaps some students feel anxious about test taking and see that the majority of the course assessment is via examinations. This may diminish their effort because they perceive that their ability to do well in the course is beyond their control. Given that student effort is related directly to academic performance (Schwinger, Steinmayr, & Spinath, 2009), final grades may be determined to some degree before the course really begins as students decide at the outset how well they will do.

Locus of control and confidence are among the disposi-tions that enhance student learning (Baldwin & Ford, 1988). Allowing students to select the weights distribution of course components thus may improve their performance as they per-ceive that they have more control over how they will be eval-uated and thus how they perform overall in the course. They can choose to reduce the influence of course components they do not feel confident about and then increase the weight of components that they perceive as personal strengths.

At the same time students often exhibit overconfidence in predicting their grades, particularly those students with lower

GPAs (Grimes, 2002). They may have an unrealistic view of their academic ability or believe that elements beyond their control may somehow work in their favor. Perhaps instituting self-selection of weights distribution can also mitigate over estimating the anticipated final course grade in low-achieving students by giving them a greater sense that their final grade is in their control.

METHOD

This exploratory research relies primarily on quantitative data analysis of a small student sample (N = 39). A grading agreement was administered on the first day of class in two sections of the undergraduate Capstone: Strategic Manage-ment course at a regional, public, liberal arts university in the Northeast with an enrollment of approximately 1,400 stu-dents. This course is required of all business management majors and is usually taken in the last semester prior to grad-uation. The agreement asked students to individually select the percentage weights distribution to be used in calculating their final grade in the course on an individual basis. The four graded components in the course included a) case preparation and class participation (10%, 15%, or 20%), (b) individual written case analyses (30%, 35%, 40%, 45%, 50%, 55%, or 60%), c) group case presentation (10%, 15%, or 20%), and d) business strategy game (15%, 20%, 25%, 30%, or 35%). Stu-dents were then asked to provide a written rationale for their selections. Each student would be graded using the weights distribution they individually selected on the grading agree-ment. Once submitted, students were not permitted to make any changes to their selections.

Students provided written responses for their rationale in selecting their weights distribution on the grading agreement. Written responses were coded based on the general theme evident in the response. For example, the rationale, “I chose a low weight for the Group Case Presentation because I am not very good at speaking in public” and “My past experience with group work has recently not been good; so I rated the Group Case Presentation and Business Strategy Game lower” were coded as “minimize particular weaknesses.”

An end-of-semester survey was administered on the last day of class to solicit student feedback on the self-selection of weights distribution process. The survey utilized a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5

(strongly agree) to assess student level of agreement with a

number of items. Each item was designed to inquire about a particular aspect of the self-selection weights distribution process. More specifically, did the grading agreement influ-ence students’ sense of control (e.g., over their time man-agement) and performance (e.g., expectations from group members)? Further, did students experience a great enough sense of control to want the exercise implemented in other courses?

TABLE 1

Percentage of Course Component Weights Distribution

Instructor Instructor Student Difference (Student

Variable Y1 Y2 Y2 Y2 – Instructor Y1)

Case preparation

aMarginal significant difference,p=.059. ∗∗p<.01.

Anecdotal comments in class suggested that students were not prepared to complete the grading agreement on the first day of class. Thus, this survey items was included to con-firm or refute this claim. These survey items are displayed in Table 2. A few items designed to collect demographic data were also included. The survey concluded with an open-ended question asking for general comments regarding self-selection of weights distribution. Coding for this question was also based on the general theme. For example, the com-ments, “I enjoyed selecting the weights for the class” and “it’s a good idea” were coded as “generally positive.”

TABLE 2

Comparison of Student Level of Agreement, by Final Grade

I wish that this approach was used in other courses in the major.

4.19 4.00 +0.19

I was prepared to select the percentage weights on the first day of class.

3.14 2.50 +0.64

As a result of selecting the percentage weights. . .

I was more motivated to do my best. 4.24 4.11 +0.13 I think my final grade will be higher. 4.24 3.17 +1.07∗ I allocated my time toward each

assignment more appropriately.

4.14 4.17 0.03

I took greater ownership over my learning.

4.14 3.94 +0.20

I expected more from my teammates. 3.86 3.44 +0.42

Note.Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from

1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

∗∗p<.01.

Final grades in the course from the previous year where the instructor determined the weights distribution for all stu-dents were also recorded to see if there was any difference in student performance based on the self-selection process. Quantitative responses from the end-of-semester survey were entered into a database and analyzed using SPSS (version 12.0).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize student se-lection of weights distribution, their rationale, and the end-of-semester student comments regarding the self-selection of weights distribution process. Samplettests were used to determine any significant differences for a number of mea-sures including the average rating on various items on the end-of-semester survey based on academic performance in the course. To do this, students with a final grade of A+

to A– were categorized as high achieving whereas students with a final grade of B+to C– were considered low achiev-ing. This made for two groups of relatively equal size (i.e., 21 and 18 students, respectively). The research goal was to determine if self-selection of weights distribution influenced student sense of control and performance.

RESULTS

The end-of-semester survey was administered to 39 under-graduate students over the two sections. Gender was rather balanced, with 43.6% female respondents. The average age of students was 23.1 years (SD=4.5), with a range of 20–43 years. All students were business management majors gradu-ating at the end of the semester and earned a passing grade of C– or better in the Capstone: Strategic Management course. Students provided a written rationale for their initial weights distribution selections on the grading agreement. Most students explained their selections as trying to maxi-mize their strengths (53.8%) or attempting to minimaxi-mize their weaknesses (30.8%). A few students tried to provide an equal distribution among the course components (7.7%), others wanted to self-impose positive pressure to improve in a par-ticular area (5.1%), or did not respond (2.6%).

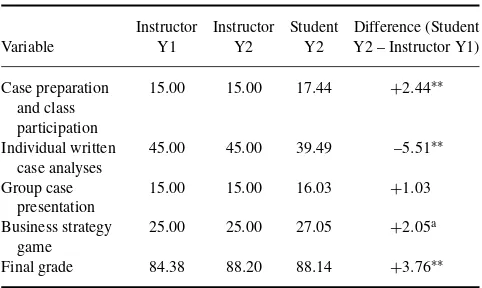

Table 1 shows the average percentage weights distribu-tion for students on the first day of class grading agreement as well as the instructor’s traditional weights distribution framework used in the present year (Year 2) and the previous year (Year 1). The results of a one-samplettest showed a sig-nificant difference between the average student weights dis-tribution and the instructor’s traditional weighting for three of the four graded course components. The instructor used each student’s individual selections to calculate their final grades in the course. It was interesting to note that using a paired samplesttest there was no significant difference (p=

.72) in the final grades in the course in Year 2 when using the student self-selection of weights distribution (88.14%) or the instructor’s traditional weighting framework (88.20%).

STUDENT PERFORMANCE AND WEIGHTS DISTRIBUTION 355

The average final grade in the course from Year 2 was com-pared to Year 1 to determine if the self-selection of weights distribution process itself influenced performance rather than using a particular weights distribution framework. The tra-ditional weights distribution framework was used for both years in the comparison. An independent samplesttest de-termined that the difference in the average final grade in Year 2 (88.14%) compared with Year 1 (84.38%) was marginally significant (p=.059).

Student comments at the end of semester regarding the self-selection of weights distribution were mixed. Some stu-dents (17.9%) were generally positive about the self-selection of weights distribution process, whereas others went further to say that the process gave them a greater sense of control (28.2%). A number of students wanted more time to make their selections (23.1%) perhaps on the second or third day of class, a few wanted more choice in terms of weighting op-tions (5.1%), and others (25.6%) did not provide a response. Overall, students felt a stronger sense of control from the self-selection process. The average rating was 4.28 out of 5 on the item “I am glad that I (as opposed to the instructor) se-lected the percentage weights for each evaluation component in the course.” The greater sense of control was also evident in students agreeing on average with three other items on the end-of-semester survey, including “As a result of select-ing the percentage weights I allocated my time towards each assignment more appropriately” (4.16) and “I took greater ownership over my learning” (4.05).

End-of-semester survey results were also analyzed on how students differed on their level of agreement with various as-pects of the self-selection process based on their academic performance in the course. Although the differences were not significant, in general high-achieving students had higher av-erage ratings on items regarding sense of control and items reflecting anticipated performance than low-achieving stu-dents. However, the difference in rating the item “As a result of selecting the percentage weights I think my final grade will be higher” by high- (4.24) and low-achieving students (3.17) was significant (p<.01).

DISCUSSION

It is not surprising that students tried to maximize their strengths or attempted to minimize their weaknesses in se-lecting their weights distribution. It was interesting to note that a few students used the experience as a challenge to im-prove by self imposing greater weight to an area of weakness. This was an unexpected outcome of the process but one that merits further exploration in terms of student self-motivation and sense of control. Encouraging students to impose their own incentives could be promising in that mastering self-management skills contributes to academic performance and success in the workplace (Gerhardt, 2007).

Contrary to the work of Stewart-Wingfield and Black (2005), giving students a voice in the grading criteria re-sulted in a marginally significant difference in student final grades. Students on average felt a greater sense of control over how their performance would be evaluated. As a result, they perceived that they had a better chance to do well in the course. This was evidenced by the overall agreement (4.18) with the survey item “As a result of selecting the percentage weights I was motivated to do my best.”

Perhaps calculating final grades using a self-selection of weights distribution does not really influence performance. Rather, it is the process of self-selecting the weights distri-bution that gives students a sense of control and ownership over their effort. It is this perception of heightened influ-ence over their destiny that leads to greater performance. As a result, students put forth greater effort and therefore at-tain higher academic performance. This was evidenced by the almost identical average final course grade in Year 2 using the instructor’s traditional grading framework or the students’ individual weights distribution. Thus the grading framework did not matter in terms of how the final grades were calculated. However, the average final course grade was marginally higher for the group of students who self-selected the weights distribution in Year 2 compared with the group in Year 1 in which self-selection of weights dis-tribution was not available. Thus student performance was positively influenced by the self-selection weights distribu-tion process.

Student written comments regarding self-selection weights distribution reflected their overall satisfaction with the process. The positive nature of comments speaks to the notion that students who perceive that they can influence their destiny regarding grades are more inclined to put forth their best effort. Students emphasized the participative el-ement by stating “I felt more in control,” “my grade was in my own hands,” and “it gave me more self-confidence.” These sentiments reflect that student lack of effort can be overcome somewhat by getting students more engaged. This engagement comes from the sense of control students gain by helping determine how what they do in the classroom may influence their performance in the course.

Students often expect grades much higher than they ulti-mately earn (Remedios, Lieberman, & Benton, 2000). This is particularly true of low-achieving students (Nowell & Alston, 2007). However, in the present study low-achieving students did not believe to the same extent as did high-achieving stu-dents that the self-selection of weights distribution process would result in earning a higher final grade in the course. Perhaps high-achieving students have a greater awareness of their academic strengths. It is also possible that even though they were given the opportunity to cater the assess-ment to their personal academic strengths and weaknesses, low-achieving students still manifested an external locus of control that contributes negatively to student learning. In ei-ther case, the self-selection of weights distribution process

appears to mitigate the tendency of low-achieving students to overestimate the final grades they will earn.

Using a traditional weights distribution framework may set many students up for discouragement (Wendorf, 2002). This can be avoided by giving students a greater sense of control over grading at the outset by allowing students to self-select the weights distribution. This study demonstrated not only that students perceived the process as meaningful, but also that it had positively influenced their academic per-formance. Although low-achieving students do not gain as great a sense of control as high-achieving students, all stu-dents on average did achieve greater academic performance when using the self-selection of weights distribution.

Limitations and Opportunities for Future Research

The results of this exploratory study are significant but there are things to consider when making direct application to the business education curriculum. The study was limited to one institution and only two sections of students in the Capstone: Strategic Management course.

A few students expressed concern about the range of per-centage weights for each component. This may have pre-cluded finding a significant difference in final grades based on the self-selection weighting and the instructor’s traditional weighting framework. Given the course was populated with graduating seniors, students tended to do well in each com-ponent thus diminishing the influence of weighting.

Conclusion

The results of this research can assist business educators in having a better understanding of how to enhance student performance. A benefit of seeing a marginally significant difference in final grades for students who participated in the self-selection of weights distribution process is that they may be more conscientious and feel a greater sense of control, which results in higher performance.

This exploratory study serves as a basis for further re-search. The open-ended responses from the end-of-semester survey should help in developing a more comprehensive sur-vey. The extended survey could then be used in a more comprehensive replicated study with a larger sample size, perhaps over several sections of the same course. The sur-vey could be administered pre- and postsemester to see if initial perceptions are consistent with end-of-semester re-flections. This would also assist in determining the level of influence the student selection method has on student mo-tivation. Insights gleaned from future inquiry in this area should further enlighten the role that the self-selection of weights distribution process has on student sense of control and student performance as well as student motivation and satisfaction.

REFERENCES

Baldwin, T. T., & Ford, K. J. (1988). Transfer of training: A review and directions for future research.Personnel Psychology,43, 63–105. Elliot, A. (2005). A conceptual history of the achievement goal construct.

In A. Elliot & C. Dweck (Eds.),Handbook of competence and motivation

(pp. 52–73). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Elliot, A., & McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2×2 achievement goal framework.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,80, 501–519.

Gerhardt, M. (2007). Teaching self-management: The design and implemen-tation of self-management tutorials.Journal of Education for Business,

83, 11–18.

Grimes, P. W. (2002). The overconfident principles of economics student: An examination of a metacognitive skill.The Journal of Economic Education,

33(1), 15–30.

Haas, A. L., Haas, R. W., & Wotruba, T. R. (1998). The use of self-ratings and peer ratings to evaluate performances of student group members.

Journal of Marketing Education,20, 200–210.

Horowitz, G. (2010). It’s not always just about the grade: Exploring the achievement goal orientations of pre-med students.The Journal of

Ex-perimental Education,78, 215–245.

Mainkar, A. V. (2008). A student-empowered system for measuring and weighing participation in class discussion.Journal of Management Edu-cation,32(1), 23–37.

Mills-Jones, A. (1999, December). Active learning in IS education: Choos-ing effective strategies for teachChoos-ing large classes in higher education. In

Proceedings of the 10th Australasian Conference on Information Systems

(pp. 5–9). Wellington, New Zealand.

Nowell, C., & Alston, R. M. (2007). I thought I got an A! Overconfidence across the economics curriculum.The Journal of Economic Education,

38, 131–142.

Pavlovich, K., Collins, E., & Jones, G. (2009). Developing students’ skills in reflective practice. Journal of Management Education,33(1), 37– 58.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). An achievement goal theory perspective on issues in motivation terminology, theory, and research.Contemporary Educational

Psychology,25, 92–104.

Remedios, R., Lieberman, D. A., & Benton, T. G. (2000). The ef-fects of grades on course enjoyment: Did you get the grade you wanted? British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 353– 368.

Rodriguez, C. (2009). The impact of academic self-concept, expectations and the choice of learning strategy on academic achievement: The case of business students.Higher Education Research & Development,28, 523–539.

Saenz, T., Marcoulders, G., Junn, E., & Young, R. (1999). The relation-ship between college experience and academic performance among mi-nority students.International Journal of Educational Management,13, 199–207.

Schwinger, M., Steinmayr, R., & Spinath, B. (2009). How do motivational regulation strategies affect achievement: Mediated by effort management and moderated by intelligence.Learning & Individual Differences,19, 621–627.

Spencer, K. J., & Labenberg, L. J. (1997). Students’ perceptions of the weight faculty place on grading criteria.Perceptual & Motor Skills,84, 1444–1447.

Stewart-Wingfield, S., & Black, G. S. (2005). Active versus passive course designs: The impact on student outcomes.Journal for Education of Busi-ness,81, 119–123.

Walvoord, B., & Anderson, V. J. (1998).Effective grading: A tool for

learn-ing and assessment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Wendorf, C. A. (2002). Grade point averages and changes in (great) grade expectations.Teaching of Psychology,29, 136–138.