Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:01

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Managerial Caring Behaviors: Development and

Initial Validation of the Model

Carolyn Keeler & Michael Kroth

To cite this article: Carolyn Keeler & Michael Kroth (2012) Managerial Caring Behaviors: Development and Initial Validation of the Model, Journal of Education for Business, 87:4, 223-229, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.606243

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.606243

Published online: 29 Mar 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 94

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.606243

Managerial Caring Behaviors: Development and

Initial Validation of the Model

Carolyn Keeler

Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, California, USA

Michael Kroth

University of Idaho, Boise, Idaho, USA

The purpose of this exploratory study was to develop a measure of managerial caring. A review of the caring literature from nursing, education, and management formed the theoretical framework for the study. The Measure of Managerial Carator Behaviors (MMCB) survey instrument was developed from an initial conceptual framework based upon a review of literature and existing instruments which measure caring. The resulting Likert-type instrument to measure managerial caring behaviors was field-tested using a sample (N=233) of managers. The MMCB was validated through a factor analysis procedure.

Keywords: caring, carator, leadership, manager, managerial

There are at least two reasons why a model and an instru-ment concerning managerial caring are relevant for business educators. The first is that caring may improve teaching out-comes, and hence be a competency worth developing for pedagogical reasons. The second is that caring may help leaders produce better business outcomes, and hence be a competency that leadership courses might put forward.

Most individuals know from personal experience a teacher who has affected their lives because they felt he or she cared about them or was passionate enough about the topic that they too became intensely interested in it. It is known, anecdotally, that a teacher who cares is going to be more effective in at least some ways than a teacher who does not, yet caring does not appear to be a topic researchers are considering. Most people have experienced a caring faculty member yet one is hard pressed to find an article on caring in a business education journal (Hawk & Lyons, 2008).

Hawk and Lyons (2008) looked at faculty pedagogical car-ing in an evencar-ing master of business administration (MBA) program. They found a paucity of published business and management journal articles on the ethic of care. Hawk and Lyons collected responses from graduate-level students from summer 2000 through fall 2002, a total of six semesters.

Correspondence should be addressed to Michael Kroth, University of Idaho, Department of Adult/Organizational Learning and Leadership, 322 E. Front Street, Boise, ID 83702, USA. E-mail: mkroth@uidaho.edu

During that period of time 44% of the students had a least one instance when they felt the instructor had given up on them and their learning in a course. The consequences of feeling given up on, Hawk and Lyons found, ranged from doing nothing, to complaining to an advisor, chair, or dean.

Alternatively, student responses were also categorized into ways that a teacher or instructor can communicate that he or she had not given up on a student. Those categories were the following: (a) instructor preparation and enthusiasm, (b) establishing a safe and encouraging environment, (c) recog-nizing student learning differences, (d) involving students and checking for comprehension, (e) providing construc-tive developmental feedback, and (f) instructor availability. Hawk and Lyons (2008) found that having a pedagogy of car-ing is a valuable attribute for business education instructors. “Demonstrating and modeling an ethic of care, pedagogical caring, and pedagogical respect,” they say, “are the appropri-ate actions for an instructor. Caring helps us to reach all of our students” (p. 333).

Are students in business classes giving up or producing less because they feel faculty have given up on them? Do they feel their instructors do not care about them? Most faculty and students know how important having a caring faculty member is but very little research or writing has been pub-lished about it. Developing a deeper understanding of caring might help faculty to become better, more engaged and en-gaging instructors, and also to improve learning outcomes for students.

224 C. KEELER AND M. KROTH

We have previously discussed that caring behaviors may also be important for managers, as described next (Kroth & Keeler, 2009). Employees appear to be an increasingly im-portant part of competitive advantage (Pfeffer, 1994), and the benefit of positive work environments is receiving increased attention from scholarly and popular perspectives (Ballou, Godwin, & Shortridge, 2003; Boyle, 2006; Edmans, 2007; Fulmer, Gerhant, & Scott, 2003; May, Lau, & Johnson, 1999; Pfeffer, 2010a). Research has shown that employees leave organizations because of poor managers (Buckingham & Coffman, 1999). Intuitively, it makes sense that if employees believe their managers care about them, then organizational benefits will result.

At the same timeFortuneandWorking Motherare publish-ing lists of the best places for employees to work, employees continue to perceive their bosses to be abusive and their work environments as negative (Ehrenreich, 2001; Fortune, 2011; Leonard, 2007; Levering et al., 2006). Flexible schedules and onsite daycare facilities are examples of strategies some em-ployers are figuring may attract talented workers. Employees who are in demand are apt to flow to the best employee value proposition in a free agent talent market (Chambers, Foul-ton, Handfield-Jones, Hankin, & Michaels, 1998). Further, workers increasingly will be less likely to be collocated, and managers will depend less on visual influence and more on less direct methods to build and sustain motivation (Clemons & Kroth, 2010). Recent literature has also focused on what sustainability means for employees in organizations, beyond just the physical environment which suggests the importance of a healthy, mutually supportive, organizational ecology (Pfeffer, 2010a). Developing a deeper understanding of man-agerial caring would provide human resource development (HRD) and management scholars, faculty, and practitioners insight into the process and practice of developing caring behaviors in managers.

Research about caring has been significant in at least two disciplines, nursing and education. It has received less atten-tion in management literature (Hawk & Lyons, 2008; Kroth & Keeler, 2009), though research about perceived organiza-tional support (POS) has been studied extensively. POS is de-fined as “global beliefs [that employees develop] concerning the extent to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well being” (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002, p. 698). It results from what employees perceive the organization is doing voluntarily to support employees.

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

The purpose of this exploratory study was to develop a mea-sure of managerial caring. A review of the caring literature from nursing, education, and management formed the theo-retical framework for the study (Kroth & Keeler, 2009). Re-searchers have developed and validated caring scales in nurs-ing (Watson, 2002), social work(Ellis, Ellett, & DeWeaver,

2007), and organizations (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchi-son, & Sowa, 1986).

To begin to develop a better understanding of manage-rial caring we developed the Measure of Managemanage-rial Carator Behaviors survey instrument (MMCB) using a Likert-type scale. We then field tested the instrument using a sample (N

=233) of managers from public and private sectors. Our intent was to develop an instrument that could be used to measure managerial caring behaviors in organizational set-tings. We were guided by two research questions:

Research Question 1: Can a valid measure of managerial

caring be developed from the dimensions identified in the education, nursing, and organizational literature?

Research Question 2:Does field-testing and analysis of the measure of managerial caring instrument confirm or sug-gest adaptations to the manager behaviors within the Recursive Model of Managerial Caring (RMMC)?

THE RECURSIVE MODEL OF MANAGERIAL–EMPLOYEE CARING

The RMMC, originally proposed as a result of an integra-tive literature review, is intended to broaden the discourse about caring as a managerial strategy by incorporating car-ing from three perspectives: nurscar-ing, education, and organi-zations (Kroth & Keeler, 2009). Although we drew only upon the Manager (Carator) Behaviors identified in the model for development of the MMCB described herein, a brief descrip-tion of the complete model, as we previously discussed (see Kroth & Keeler, 2009) follows next. The MMCB was not designed to measure the entire model but only managerial caring behaviors.

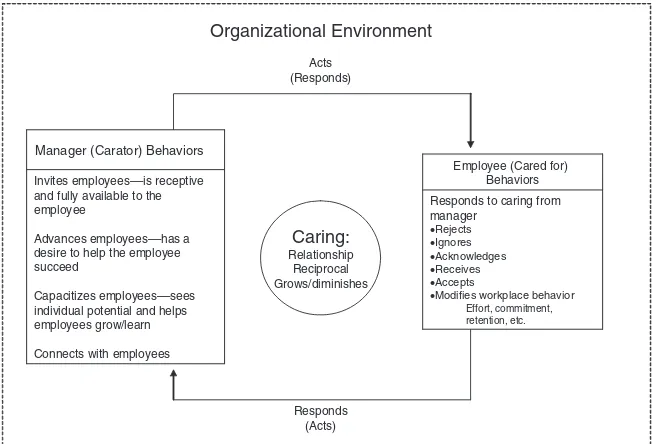

The model, shown as Figure 1, suggests that caring is a reciprocal process. Both the manager and the employee must be active agents in order to enable the process. The manager invites, advances, capacitizes, and connects with employees. Employees respond in ways that reinforce the caring cycle or that do not. Specifically, the employee may react to the manager’s behaviors by rejecting, ignoring, acknowledging, receiving, or accepting them, and also modifies his or her work behavior as a result. These actions by the employee then affect the manager’s actions, and the cycle continues.

This reciprocal process also suggests, as shown by the caring circle in the middle of the model, that caring, exhibited by caring behaviors (manager and employee) may expand or contract over time based upon the other’s actions. The arrows in the model reflect this recursive process. Managers act with caring behaviors and employees then respond, which affects managerial caring behavior, and the process then continues either building or diminishing caring behaviors.

The environment also affects each person’s caring ca-pacity (Kroth & Keeler, 2009). If the environment is healthy then the players are more likely to be open to the

Organizational Environment

Acts (Responds)

Responds (Acts)

Caring:

Relationship Reciprocal Grows/diminishes

Responds to caring from manager

•Rejects

•Ignores

•Acknowledges

•Receives

•Accepts

•Modifies workplace behavior Effort, commitment, retention, etc.

Employee (Cared for) Behaviors Invites employees–is receptive

and fully available to the employee

Advances employees–has a desire to help the employee succeed

Capacitizes employees–sees individual potential and helps employees grow/learn

Connects with employees Manager (Carator) Behaviors

FIGURE 1 Recursive Model of Managerial–Employee Caring (Kroth & Keeler, 2009).

development of a caring relationship. If the environment is negative the opportunity is likely to be less so.

Inviting behaviors on the part of the manager suggest an engaging, open atmosphere and that the leader is available emotionally and cognitively to understand the employee’s in-terests. Advancing behaviors place the manager on the side of the employee as an active agent on his or her behalf. Ca-pacitizing behaviors are those actions the manager takes to help the employee learn, grow, problem solve, and stay on track. Finally, connecting behaviors are what the manager does to develop mutuality of relationship with the employee. The first three categories are more focused on what the man-ager does for the employee; this category represents the de-veloping relationship of common interest between the two parties.

The RMMC addresses important gaps in organizational literature by proposing a process of caring, behaviors that managers can practice to produce caring relationships, and the part employees play within the process. The model sug-gests that employees are not passive agents, waiting to be acted on, but have a viable role in the process. Further, al-though we believe a caring attitude is more important than going through the motions of expected caring behaviors, we propose behaviors that may be learned by the manager. Fi-nally, the model suggests, building upon POS literature, that managerial caring behaviors are antecedents to desired em-ployee outcomes such as productivity, retention, organiza-tional citizenship behavior, and job satisfaction.

In addition to nursing (Swanson, 1991) and educational (Noddings, 2005) caring theory, and POS research (Eisen-berger et al., 1986), the model was further influenced by so-cial exchange and leader–member exchange (LMX) theory

(Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Foa & Foa, 1974; Gerstener & Day, 1997; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Social exchange the-ory suggests that resources such as love, status, money, and information can be exchanged in any situation, which then creates obligations between the players. LMX posits that re-lationships develop between leaders and followers, based on exchanges between them, starting with stranger and progress-ing to mature partnership (Graen & Uhl-Bien). In this section we have summarized the RMMC. Next, we describe the de-velopment of an instrument to measure managerial caring behaviors.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE MMCB SURVEY INSTRUMENT

The fields of nursing, education, and management were ex-amined for instruments on caring. As we have previously discussed, briefly described here in terms of the develop-ment of the MMCB survey instrudevelop-ment, a review of the literature on caring in nursing and education shows a sig-nificant empirical and theoretical base (Kroth & Keeler, 2009). Perhaps the most research and theory building con-cerning caring has been conducted in the field of nursing. Although caring historically has been considered an inte-gral part of nursing, systematic research and theory building about nursing and caring began in the late 1970s, and theo-rizing began at least as early as the 1950s (Leininger, 1978; Watson, 1985, 2002).

Numerous studies have been conducted and outcomes of caring have been identified and summarized via a meta-analysis (Swanson, 1999). Swanson (1991) definedcaringas

226 C. KEELER AND M. KROTH

“a nurturing way of relating to a valued other toward whom one feels a personal sense of commitment and responsibil-ity” (p. 162). Her caring theory, comprising five categories or processes—knowing, being with, doing for, enabling, and maintaining belief—has been shown to have generalizability and transferability across a range of settings (Swanson, 1999; Watson, 2002).

Each of these has subdimensions. Knowing, to Swanson (1991), is “striving to understand an event as it has meaning in the life of another” (p. 163). Being with is “being emotionally present to the other” (p. 163). Doing for is “doing for the other what he or she would do for the self if it were at all possible” (p. 164). Enabling is “facilitating the other’s passage through life transitions and unfamiliar events” (p. 164). Maintaining belief is “sustaining faith in the other’s capacity to get through an event or transition and face a future with meaning” (p. 165).

Nel Noddings’s (2005) work provides the foundation for caring theory in education. Caring, she says, is the “bedrock of all successful education” (p. 27). The complexity of car-ing is explicated in Noddcar-ings’ theory. Carcar-ing, to Noddcar-ings, also depicted in our RMMC, is a relationship between the caregiver and the cared for. Both parties must be contributors to the relationship in order for it to be called caring. The carer (the one who is giving care), Noddings said, exhibits engrossment and motivational displacement. Engrossment is “open, nonselective receptivity to the cared-for” (Noddings, p. 15). Motivational displacement is the desire on the part of the care giver to help the other. Displacement occurs as the caregiver’s focus shifts from his or her plans to those of the cared-for.

The Revised Human Caring Inventory (RHCI; Ellis et al., 2007) is grounded in Noddings’ (2003, 2005) concept of caring. It was originally adapted from the Human Caring In-ventory (HCI) for Nurses (Moffett, 1993) and has been used to study the retention and turnover of public child welfare workers. The original measure had 33 items and four di-mensions of the affective component of caring: receptivity, responsivity, moral–ethical consciousness, and professional commitment. The six empirically verified dimensions which are retained from the latest study are receptivity, personal responsibility–reward, commitment to clients, professional commitment, personal attachment, and respect for clients (Ellis et al.).

Research about perceived organizational support consid-ers caring in the managerial literature. POS is defined as “global beliefs [that employees develop] concerning the ex-tent to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well being” (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002, p. 698). It results from what employees perceive the orga-nization is doing voluntarily to support employees. A meta-analysis of 70 empirical studies indicated that POS correlated with outcomes such as performance, organizational commit-ment, and job satisfaction (Hellman, Fuqua, & Worley, 2006; Rhoades & Eisenberger).

METHOD

In this section we explain item development, procedures, and participant selection. Studies that involve instrument devel-opment are important and infrequent. Considerable time was allocated to item development using multiple sources. The process will be described in the first part of this section. Then the procedures used and participants in the study will be explained.

Item Development

An inductive approach assisted in the development of ap-propriate items for the MMCB. A review of the literature as described previously gave us a broad understanding of the theoretical and empirical work that has been undertaken to explain caring in organizational, nursing, and educational settings. First, we developed a conceptual model, the Re-cursive Model of Managerial–Employee Caring from that review (Kroth & Keeler, 2009). Second, we began to develop an instrument to measure managerial caring. The pool of items examined initially was obtained from two instruments, the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (Eisenberger et al., 1986) and the RCHI (Ellis et al., 2007). In addition, Swanson’s Caring Theory (1991, 1999) provided the ini-tial framework around which items were organized and also served as a source for additional items.

Developed as a 36-item self-report measure, the Survey of Perceived Organizational Support (SPOS) has been used in shorter versions, including those with 8 and 16 items. Studies have even used as few as three items (Hellman et al., 2006). The original 36 items were developed by Eisen-berger et al. (1986) “to test the globality of the employees’ beliefs concerning support by the organization” (p. 501). Each statement was examined for its fit to the concep-tual model. An example of an 8-item version included the following:

My organization cares about my opinions. My organization really cares about my well-being. My organization strongly considers my goals and values. Help is available from my organization when I have a

problem.

My organization would forgive an honest mistake on my part.

If given the opportunity, my organization would take ad-vantage of me. (R)

My organization shows very little concern for me. (R) My organization is willing to help me if I need a special

fa-vor. (Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli, & Lynch, 1997, p. 815)

Swanson’s (1999) meta-analysis of caring in nursing pro-vided another framework in the planning stage of working on the instrument. She categorized behaviors from the stud-ies she reviewed using her caring categorstud-ies—maintaining

belief, knowing, being with, doing for, and enabling—and utilizing subcategories. Items from the RHCI and the SPOS were integrated into this framework and examined further in terms of their relevance to the model.

All items were examined for a fit to the Manager (Carator) Behaviors listed within the RMMC model. In addition, some areas required that more items be developed and we under-took an iterative process, constantly comparing them to the behaviors named in the research. A small group of middle managers reviewed and discussed each item. The criteria set for inclusion in this group included management experience, availability, and familiarity with research in the management field. All were from course enrollments in an adult education doctoral program. Some changes in wording resulted that made them personally relevant to managers.

Developed and revised items were then fit to the manager behaviors in the model and through discussion, revision, and elimination 63 items were retained for testing. Constructed as a Likert-type survey, a 4-point scale was utilized, with values ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) to force choice selections to one side of the scale or the other. In Likert-type scaled instruments, negatively worded items are often used to test for responses that are not aligned with the intent of the instrument. Completed surveys with all items answered in the same direction are not considered a valid reflection of the caring demonstrated by managers and would be discarded. To increase validity, we designed the instrument with 18 negatively worded items.

Procedures and Participants

A survey including the 63 items generated previ-ously was constructed and administered electronically through the use of Zoomerang online survey software (http://www.zoomerang.com). Leaders in each organization were contacted and participation was based on their agree-ment to give access through interorganizational networks to manager’s emails, not receive results, and guarantee anonymity. This allowed for participation to be voluntary and anonymous for the managers.

Email lists were utilized by human resources and other leaders who forwarded an invitation to participate and the website for survey access to managers within the organiza-tion. The voluntary nature of participation and lack of in-centives may have resulted in the number of participants from each organization to vary: a low of one to a high of 123 responses per organization were received. Only those responses from complete surveys were retained. The result-ing 233 complete responses were obtained from managers in financial, health, agricultural, city and state government, high technology, catalog consumer products, employment agency, and restaurant supply organizations. This large and varied sample was necessary to increase the number of re-turns and, thereby, the statistical power of the test to find significant factors.

RESULTS

Several psychometric analyses were used to identify the mea-surement items to retain and determine the validity of the four factors hypothesized in the development stage. We also con-ducted a test to determine reliability. First, a printout of the data from the 233 responses to the survey was scanned to check for any respondent who scored all items in the same direction, (i.e., all 3 or 4 or all 1 or 2). This initial validity check found no such entries. A frequency count was used to determine the ability of the respondents to discriminate their beliefs in terms of the level of agreement with each state-ment. Of the 63 original items, all had good discriminatory power in that none of them contained a response that had been chosen by more than 75% of the respondents. There-fore, no items were eliminated from the pool for appearing to be overly socially desirable.

The negatively worded items then were reverse scored using Excel and a formula that replaced 4s with 1s and 3s with 2s, and so on. This is necessary to prevent ambiguity in that all high scores should reflect a high degree of agree-ment with the construct of caring being measured. Next a total correlation was run on responses on all 63 items. The overall reliability estimate was a Cronbach’s alpha of .947. This is a strong correlation that promoted the next step. An exploratory factor analysis was used to uncover the latent structure or dimensions of the original items. This procedure was used to reduce the large number of variables to a smaller number of factors for modeling the construct managerial car-ing (McLean, Yang, Kuo, Tolbert, & Larkin, 2005).

A principle component factor analysis was run using SAS (Version 9.2, Cary, NC) to determine the construct validity of the total instrument. An eigenvalue plot was constructed and examined to determine the amount of variation in the total sample accounted for by each factor. The scree plot flat-tened after the fifth factor suggesting that the first five factors contributed significantly to the construct being measured, managerial caring.

The general factor was held fixed and using the SAS vari-max rotation procedure the other factors were rotated. Six eigenvalues met the Kaiser criterion of being greater than one. Because the Kaiser criterion suggested six factors and the scree test suggested five, a six-factor analysis as well as four- and five-factor analyses were run. This allowed each re-sult to be examined as to the degree each met the criterion of theoretical meaningfulness. We then searched each resulting analysis for the solution that generated the most comprehen-sible factor structure. The purpose of this scrutiny of each factor analysis was to find what was interpretable as well as the best cognitive fit to the model. This comprehensibility criterion was used to interpret the findings. It was evident that the six-factor solution, indicated by the Kaiser criterion, presented the most interpretable results.

Examination of the pattern matrix showed a fairly sim-ple factor structure and close fit to the theoretical foundation

228 C. KEELER AND M. KROTH

and substantive meanings of the model. The fixed or central factor is considered a general measure of managerial caring and is therefore not analyzed for agreement to the model. Cognitively, three of the five remaining factors were similar to three of the four factors hypothesized from the litera-ture. They also contained evidence of some fit to the five factors originally proposed by Swanson (1991). Due to the exploratory nature of this factor analysis and present statisti-cal thinking (Garson, 2008; Raubenheimer, 2004), we used the factor loading criteria of .4 or higher for the central factor and .25 or higher for the other factors. Items that had loadings >.40 were retained in the five factors defined; 11 items did not load adequately into the general factor or the other five factors meeting our criteria and were eliminated.

By examining the items in each factor hypothesized from the literature, it was determined which ones were a good fit to the theoretical construct indicated. Of the nine items that contributed to the concept referred to previously as “invites,” three items had poor cognitive fit. One item was dropped and two items had loadings of almost equal value in two other factors and were thus moved, one to capacitizes and one to values. This left invites with six strong component loadings. Due to the makeup of the items loading in this factor, we renamed it “communicates.” The concept of advances had seven items loading at the criterion value and all were a good fit. The concept of capacitizes had five original items and the repositioning of the item from invites, also with a loading of more than .25, resulted in six items assigned. The fourth concept hypothesized as connects, the least developed in the literature, became two separate factors in the six-factor model. One retained the cognitive meaning of connects and the other we renamed “values”. The factor connects had five items at the criterion value, meeting the criterion of three high, interpretable loadings (Garson, 2008). Values had five original items at the criterion and one additional item repo-sitioned from invites, which resulted in six items, all above the .25 loading criterion.

This process of examining the five rotated factors and renaming all factors to better represent and detail the distinc-tion among the factors resulted in an instrument of 52 items. These results indicate that the original four-concept structure of managerial caring is confirmed in part and expanded to include a fifth concept of values, a positive outcome for model testing. However, some items did not perform as well as others. Twenty-one of the items that loaded only on the general factor of managerial caring and did not contribute significantly (>.25) to the individual factors are retained at this time. They contributed significantly to the managerial caring concept and need to be tested further to see if they may contribute to one of the factors identified by this analysis.

In summary, the selection of the highest factor loadings for each of the five identified dimensions of managerial caring resulted in the following instrument: General factor with 21 items, communicates with six, advances with seven,

capacit-izes with six, connects with five, and the additional dimension of values with six items. The balance and number of items attributed to each dimension is one indicator of a strong in-strument. It is our intention to use the resulting measurement instrument for further confirmatory analysis.

DISCUSSION

Limitations

The original sample included 233 managers from financial, health, agricultural, city and state government, high technol-ogy, catalog consumer products, employment agency, and restaurant supply organizations. A sample of over 300 was suggested by Thompson (2004) and thus we fell short of this goal. The resulting structure coefficients<.4 may have been a result of the fact that the managers came from different institutions and environmental factors at play in each place may have resulted in managers’ attitudes differing due to culture and institutional goals. Due to the sampling, there-fore, these confounding variables cannot be eliminated. It will be important, therefore, to test the MMCB survey in-strument resulting from this study within a single institution. We feel that this may help to eliminate some of the vari-ance that resulted in split loadings, which in turn made the interpretation of factors more difficult. The next step in our research is to derive a new factor solution from the remain-ing 52-item survey in a large organization with more than 300 managers.

Conclusion

Two research questions guided our study. In response to the first research question and from the results presented here, we conclude that a valid measure of managerial caring was de-veloped using the dimensions from the three complementary fields of education, nursing, and organizational support. The field testing of the measure showed the instrument to be valid and internally reliable. In answer to the second research ques-tion, the results confirmed four manager behaviors shown in the RMMC model. Invites was broadened to communicates, and advances, capacitizes, and connects were retained. The factor analysis also indicated an expansion to include a fifth factor, values.

Further research using the survey that resulted from this study within a single organization appears to be the next step. Some contacts within the healthcare field have been made to access the interest in participation and to explain the information that the organization would receive as a result. It seems that public and private organizations could benefit from feedback to managers regarding their caring behaviors. Additionally, survey adaptation and research in the field of educational management could result in another application of the concept of caring leadership.

REFERENCES

Ballou, B., Godwin, N. H., & Shortridge, R. T. (2003). Firm value and em-ployee attitudes on workplace quality.Accounting Horizons, 17, 329–341. Boyle, M. (2006). Happy people, happy returns.Fortune,153(1), 100. Buckingham, M., & Coffman, C. (1999).First break all the rules: What

the world’s greatest managers do differently. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Chambers, E. G., Foulton, M., Handfield-Jones, H., Hankin, S. M., & Michaels, E. G. III. (1998). The war for talent. McKinsey Quarterly, 3, 45–57.

Clemons, D., & Kroth, M. S. (2011).Managing the mobile workforce : leading, building, and sustaining virtual teams. New York: McGraw-Hill. Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An

interdisciplinary review.Journal of Management,31, 874–900. Edmans, A. (2007, November 13). Does the stock market fully value

intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=985735

Ehrenreich, B. (2001).Nickel and dimed: On (not) getting by in America. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

Eisenberger, R., Cummings, J., Armeli, S., & Lynch, P. (1997). Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. Jour-nal of Applied Psychology,82, 812–820.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology,71, 500–507.

Ellis, J. I., Ellett, A. J., & DeWeaver, K. (2007). Human caring in the social work context: Continued development and validation of a complex measure.Research on Social Work Practices,17, 66–76.

Foa, U. G., & Foa, E. B. (1974).Societal structures of the mind. Springfield, IL: Thomas.

Fortune. (2011). 100 best companies to work for.Fortune,163(2), 91. Fulmer, I. S., Gerhant, B., & Scott, K. S. (2003). Are the 100 best better? An

empirical investigation of the relationship between being a “great place to work” and firm performance.Personnel Psychology,56, 965–993. Garson, G. D. (2008). Factor analysis. Retrieved from

http://www2.chass.ncsu.edu/garson/PA765/factor.htm

Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1997). Meta-analytic review of leader-member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology,82, 827–844.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to ership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of lead-ership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective.

The Leadership Quarterly,6, 219–247.

Hawk, T. F., & Lyons, P. R. (2008). Please don’t give up on me: When faculty fail to care.Journal of Management Education,32, 316–338. Hellman, C. M., Fuqua, D. R., & Worley, J. (2006). A reliability

generaliza-tion study on the survey of perceived organizageneraliza-tional support: The effects

of mean age and number of items on score reliability.Educational & Psychological Measurement,66, 631–642.

Kroth, M., & Keeler, C. (2009). Caring as a managerial strategy.Human Resource Development Review,8, 506–531.

Leininger, M. M. (1978).Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, and practices. New York, NY: Wiley.

Leonard, B. (2007). Study: Bully bosses prevalent in U.S. work-places. Retrieved from http://www.shrm.org/hrnews published/archives/ CMS 020939.asp

Levering, R., Moskowitz, M., Levenson, E., Mero, J., Tkaczyk, C., & Boyle, M. (2006). And the winners are. . .Fortune,153, 89–108.

May, B., Lau, R., & Johnson, S. (1999). A longitudinal study of quality of work life and business performance.South Dakota Business Review,

58(2), 1–7.

McLean, G. N., Yang, B., Kuo, M.-H. C., Tolbert, A. S., & Larkin, C. (2005). Development and initial validation of an instrument measuring managerial coaching skill.Human Resource Development Quarterly,16, 157–178.

Moffett, B. (1993).Development and construct validation of an instrument to measure caring in the helping professions. Unpublished doctoral dis-sertation, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA.

Noddings, N. (2003).Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education(2nd ed.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Noddings, N. (2005).The challenge to care in schools: An alternative

ap-proach to education(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press. Pfeffer, J. (1994).Competitive advantage through people: Unleashing the

power of the work force. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press. Pfeffer, J. (2010a). Building sustainable organizations: The human factor.

Academy of Management Perspectives,24, 34–45.

Pfeffer, J. (2010b). Lay off the layoffs.Newsweek,155(7), 32–37. Raubenheimer, J. E. (2004). An item selection procedure to maximize scale

reliability and validity.South African Journal of Industrial Psychology,

30(4), 59–64.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature.Journal of Applied Psychology,87, 698–714. Swanson, K. (1991). Empirical development of a middle range theory of

caring.Nursing Research,40, 161–166.

Swanson, K. (1999). What’s known about caring in nursing science: A literary meta-analysis. In A. S. Hinshaw, S. Feetham, & J. L. F. Shaver (Eds.),Handbook of clinical nursing research(pp. 31–60). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Thompson, B. (2004).Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: Un-derstanding concepts and applications. Washington DC: American Psy-chological Association.

Watson, J. (1985).Nursing: The philosophy and science of caring. Boulder, CO: Colorado Associated University Press.

Watson, J. (2002).Assessing and measuring caring in nursing and health science. New York, NY: Springer.