ABSTRACT

Yustina Priska Kisnanto. 2014. The Application of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) Principles in a Web-Based Sentence Writing Class. Yogyakarta: The Graduate Program in English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University.

With the advanced development of computer and Internet technologies, web-based learning, as one implementation of CALL, has been seen as a new alternative way in catering the needs of L2 writing learning. Specific descriptive investigation on how computer and web-based technologies should best be used to facilitate learning, however, is not yet fully developed, indicating a framework for teaching and learning using such technologies needs to be explored further. This study, therefore, aimed at verifying the theory of CALL principles, i.e. the eight conditions for optimal CALL environments by Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999), applied in a web-based writing class. It is elaborated into three research questions focusing on (a) investigating the intensity of the application of the CALL principles in a web-based Sentence Writing class as experienced by the students, (b) finding out whether the application of the CALL principles enhances the students’ learning achievement, and (c) examining how the application of the CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class enhanced the students’ learning achievement.

This study applied a mixed-method research approach using a survey and an experimental research designs. The data were collected through questionnaire, consisting of closed-ended and open-ended items, interviews, and teacher’s document of the students’ scores. It employed triangulation as the validation strategy using interview and a statistical t-test. The participants of the survey were 151 students while the participants for the experiment were 22 students. The students were the English Letters students of Sanata Dharma University, taking Writing 1 course, or Sentence Writing, in the first semester of the academic year 2013/2014.

▸ Baca selengkapnya: the sentence implies that

(2)application of the CALL principles. The possible interference factors are not discussed in the present study. Further, the results of the open-ended questionnaire and interviews reveal that the application of the CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class enhances the students’ achievements regarding better grammar understanding, improved sentence writing skill, and improved passage writing ability. The application of the CALL principles in Sentence Writing class is realized through the features and facilities of the web-based class. As the students advantage the class facilities for learning, they experience the CALL principles applied and thus, achieve learning improvement.

ABSTRAK

Yustina Priska Kisnanto. 2014. The Application of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) Principles in a Web-Based Sentence Writing Class. Yogyakarta: The Graduate Program in English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University.

Dengan perkembangan terkini teknologi komputer dan internet, pembelajaran berbasis web, sebagai salah satu implementasi CALL (Computer-Assisted Language Learning), telah dilihat sebagai cara alternatif baru dalam melayani kebutuhan pembelajaran menulis bahasa kedua. Meskipun demikian, studi-studi deskriptif yang spesifik membahas tentang bagaimana sebaiknya komputer dan teknologi berbasis web harus digunakan untuk memfasilitasi pembelajaran belum sepenuhnya dikembangkan. Hal ini menunjukkan kerangka kerja untuk mengajar dan belajar menggunakan teknologi tersebut perlu dieksplorasi lebih lanjut. Oleh karena itu, penelitian ini bertujuan untuk memverifikasi teori prinsip CALL, yaitu delapan kondisi untuk lingkungan CALL yang optimal oleh Egbert, Chao, dan Hanson-Smith (1999), dalam penerapannya di kelas menulis berbasis web. Hal ini dijabarkan dalam dua objektif penelitian yang berfokus pada (a) menyelidiki intensitas penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL di kelas Sentence Writing yang berbasis web dilihat dari sudut pandang para siswa, (b) menyelidiki apakah penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL di kelas Sentence Writing yang berbasis web meningkatkan prestasi belajar siswa, dan (c) meneliti bagaimana penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL di kelas Sentence Writing yang berbasis web meningkatkan prestasi belajar siswa.

Penelitian ini menggunakan pendekatan penelitian mixed-method, dengan menerapkan survei dan eksperimen sebagai desain penelitiannya. Data penelitian didapat melalui kuesioner, yang terdiri dari item tertutup dan terbuka, wawancara, dan dokumen pengajar berisi nilai-nilai para mahasiswa. Penelitian ini menggunakan triangulasi sebagai strategi validasi berupa wawancara dan uji statistik t-test. Para partisipan survei adalah 151 mahasiswa, sedangkan partisipan untuk eksperimen berjumlah 22 mahasiswa. Partisipan penelitian ini adalah mahasiswa Sastra Inggris di Universitas Sanata Dharma, yang mengambil mata kuliah Writing 1, atau Sentence Writing, pada semester pertama tahun akademik 2013/2014 .

yang berbasis web. Meskipun demikian, hasil ini tidaklah absolut karena experimen di sini hanya melibatkan satu tritmen tanpa memiliki grup kontrol. Sehingga, ada kemungkinan terdapat faktor lain yang mempengaruhi peningkatan prestasi belajar siswa di kelas Sentence Writing berbasis web ini selain penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL. Adapun faktor-faktor lain yang mungkin mempengaruhi peningkatan tersebut tidak dibahas di penelitian ini. Selanjutnya, hasil kuesioner item terbuka dan wawancara mengungkapkan bahwa penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL di kelas Sentence Writing yang berbasis web ini meningkatkan prestasi siswa dalam pemahaman yang lebih baik akan tata Bahasa Inggris, meningkatkan kemampuan menulis kalimat, dan meningkatkan kemampuan menulis bacaan. Penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL dalam kelas Sentence Writing diwujudkan melalui fitur dan fasilitas kelas berbasis web ini. Saat siswa memanfaatkan fasilitas kelas untuk belajar, mereka mengalami prinsip CALL yang diterapkan dan dengan demikian, mereka mencapai peningkatan pembelajaran..

i

THE APPLICATION OF COMPUTER-ASSISTED LANGUAGE

LEARNING (CALL) PRINCIPLES IN A WEB-BASED

SENTENCE WRITING CLASS

A THESIS

Presented as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Magister Humaniora (M.Hum) Degree

in English Language Studies

by

Yustina Priska Kisnanto Student Number: 126332049

THE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE STUDIES SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

iv

STATEMENT OF WORK ORIGINALITY

This is to certify that all ideas, phrases, sentences, unless otherwise stated are the ideas, phrases, and sentences of the thesis writer. The writer understands of the full consequences including degree cancellation if she took somebody else‟s ideas, phrases, or sentences without proper references.

Yogyakarta, January 27, 2014

v

LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PUBLIKASI PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS

Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma:

Nama : Yustina Priska Kisnanto NIM : 126332049

Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul:

THE APPLICATION OF COMPUTER-ASSISTED LANGUAGE LEARNING (CALL) PRINCIPLES IN A WEB-BASED SENTENCE

WRITING CLASS

beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). Dengan demikian saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpan, mengalihkan dalam bentuk media lain, mengelola dalam bentuk pangkalan data, mendistribusikan secara terbatas, dan mempublikasikan di internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan akademis tanpa perlu minta ijin dari saya maupun memberikan royalti kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis.

Demikian pernyataan ini yang saya buat dengan sebenarnya. Dibuat di Yogyakarta

Pada tanggal : 27 Januari 2014

Yang menyatakan

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all I would like to thank my Lord Jesus Christ for always staying by my side, loving me, and strengthening me to complete my thesis. My deepest gratitude also goes to my thesis advisor, Dr. B. B. Dwijatmoko, M.A. for his time, patience, help, and suggestions to finish my the thesis.

I am also thankful for having great lecturers while studying in the Graduate Program in English Language Studies of Sanata Dharma University. Especially to Dr. J. Bismoko, F.X. Mukarto, Ph.D., Dr. B. B. Dwijatmoko, M.A., Dr. Fr. Alip, M.Pd., Prof. Dr. C. Bakdi Soemanto, Dr. Novita Dewi, M.S., M.A.(Hons), Widya Kiswara, S.Pd., M.Hum., and Dr. Mutiara Andalas, S. J., I greatly express my gratitude and many thanks for sharing their precious knowledge and experiences in their classes.

vii

Finally, for the love, encouragement, and friendships, I send my special gratitude to my best friends Denyuk, Caca, Nina, Achenk, Pika, Mami, and Bibhow. To my lovely 2012 ELS friends, especially Pepy and Adesia, I thank them for their moral supports and kindness while studying together throughout the unforgettable moments at the Graduate Program in English Language Studies of Sanata Dharma University.

viii

LEMBAR PERNYATAAN UNTUK PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH... v

CHAPTER II. LITERATURE REVIEW... 12

A. Theoretical Review... 12

1. Writing... 12

a. The Nature of Writing... 13

b. L2 Writing Teaching... 16

c. Sentence Writing... 18

d. Passage Writing... 22

e. Student Achievement in Writing... 23

2. Computer-Assisted Language Learning & the Principles... 26

a. Interaction... 28

b. Authentic Audience... 29

c. Authentic Tasks... 30

d. Opportunities for Language Exposure and Production... 31

e. Enough Time and Feedback... 32

f. Attention to the Learning Process... 33

g. Atmosphere with an Ideal Stress/Anxiety Level... 34

h. Learner Autonomy...34

3. Teaching Writing Using Web-Based Technology... 36

4. Web-Based Sentence Writing Class... 38

a. Sentence Writing Class... 38

b. Features by ELTGallery... 43

1) Topic Selection... 44

ix

5. Sentence Writing Class‟ Students... 56

6. Review of Related Studies... 57

B. Theoretical Framework... 60

CHAPTER III. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY... 65

A. Research Method...65

B. Research Design... 67

C. Research Setting and Participants... 70

D. Data Gathering Techniques... 71

E. Data Analysis...74

F. Research Procedures and Validation... 77

CHAPTER IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS... 81

A. The Application of CALL Principles by the Web-Based Sentence Writing Class... 81

1. Data Presentation... 82

a. Data from the questionnaire...82

b. Data from the interview... 88

2. CALL Principles in Sentence Writing Class... 92

a. Authentic tasks...93

b. Opportunities for language exposure and production... 96

c. Attention to learning process... 99

d. Learner autonomy... 102

e. Interaction... 105

f. Atmosphere... 108

g. Enough time and feedback... 113

h. Authentic audience... 116

B. The enhancement of the students‟ learning achievement in the web-based Sentence Writing class... 119

1. Data Presentation... 120

a. Data from the t-test... 120

b. Data from the questionnaire... 123

c. Data from the interview... 126

2. The Enhancement of the Students‟ Achievement... 127

a. Understanding of English Grammar... 129

b. Sentence Writing Skill... 132

x

CHAPTER V. CONCLUSIONS AND SUGGESTIONS... 141

A. Conclusions... 141

B. Suggestions... 145

BIBLIOGRAPHY... 148

xi

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1 Micro and macro skills of writing (Brown 2004: 221)... 15

Table 2.2 The principal orientations to L2 writing teaching (Hyland 2003: 23)... 16

Table 2.3 Potential advantages and disadvantages of computer-assisted writing (Ferris & Hedgcock 2005: 347)... 36

Table 2.4. ELTGallery features and the observable CALL principles... 62

Table 4.1. Degrees of agreement of the questionnaire...82

Table 4.2. Students‟ response distribution of the closed-ended questionnaire... 83

Table 4.3. Scoring criteria for data interpretation... 87

Table 4.4. The score interpretation of the CALL principles applied... 87

Table 4.5. Samples of interview about CALL principles applied... 89

Table 4.6. Paired sample t-test results... 121

Table 4.7. Aspects of the Sentence Writing class and students‟ achievement (from the open-ended items of questionnaire)... 123

xii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1. The relationship of learning experience to learning outcomes

(Miller, Linn, & Gronlund 2009: 51)... 23

Figure 2.2. Syllabus of Writing 1 course... 39

Figure 2.3. Sentence Writing Classroom Situation... 41

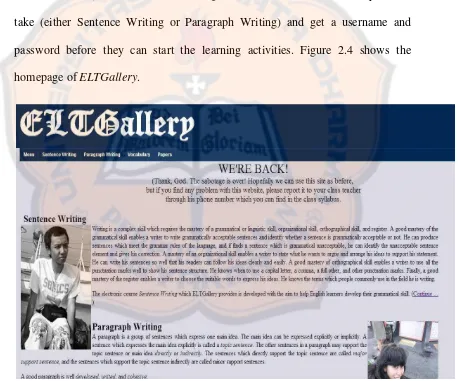

Figure 2.4. ELTGallery‟s homepage... 43

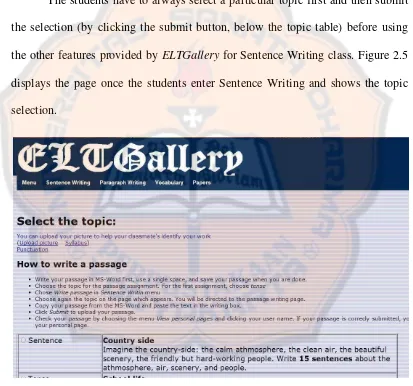

Figure 2.5. Topic selection for Sentence Writing... 44

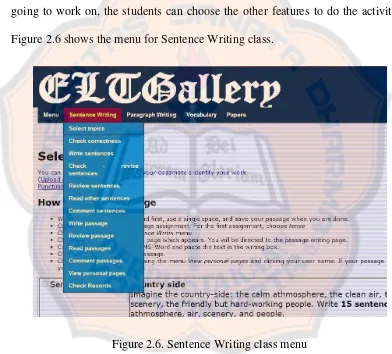

Figure 2.6. Sentence Writing class menu... 45

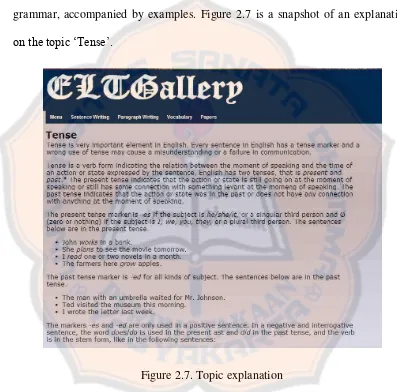

Figure 2.7. Topic explanation... 46

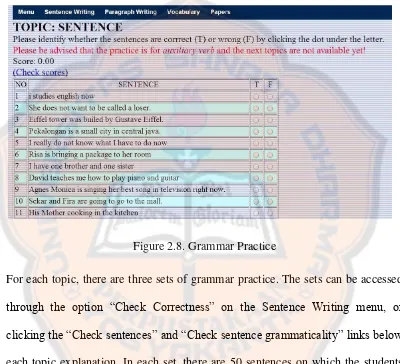

Figure 2.8. Grammar Practice ... 47

Figure 2.9. Writing Sentences... 48

Figure 2.10. Check and revise sentences... 48

Figure 2.11. Passage Writing Selection... 49

Figure 2.12. Passage Writing... 50

Figure 2.13. Sentence Review... 50

Figure 2.14. Passage Review... 51

Figure 2.15. Personal Page... 52

Figure 2.16. Sentence Comment... 52

Figure 2.17. Passage Comment... 53

xiii

LIST OF APPENDICES

Appendix 1: The Blueprint of Data Gathering... 152

Appendix 2: Questionnaire for the Data Collection... 155

Appendix 3: Interview Guideline... 153

Appendix 4: Complete Interviews... 160

Appendix 5: Complete scores of the closed-ended questionnaire results per item and the interpretation... 178

Appendix 6: Complete samples of interview about CALL principles applied in Sentence Writing class... 187

Appendix 7: Students‟ responses of the open-ended questionnaire... 194

Appendix 8: Complete samples of students‟ open-ended questionnaire responses... 231

xiv ABSTRACT

Yustina Priska Kisnanto. 2014. The Application of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) Principles in a Web-Based Sentence Writing Class. Yogyakarta: The Graduate Program in English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University.

With the advanced development of computer and Internet technologies, web-based learning, as one implementation of CALL, has been seen as a new alternative way in catering the needs of L2 writing learning. Specific descriptive investigation on how computer and web-based technologies should best be used to facilitate learning, however, is not yet fully developed, indicating a framework for teaching and learning using such technologies needs to be explored further. This study, therefore, aimed at verifying the theory of CALL principles, i.e. the eight conditions for optimal CALL environments by Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999), applied in a web-based writing class. It is elaborated into three research questions focusing on (a) investigating the intensity of the application of the CALL principles in a web-based Sentence Writing class as experienced by the students, (b) finding out whether the application of the CALL principles enhances the students‟ learning achievement, and (c) examining how the application of the CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class enhanced the students‟ learning achievement.

This study applied a mixed-method research approach using a survey and an experimental research designs. The data were collected through questionnaire, consisting of closed-ended and open-ended items, interviews, and teacher‟s document of the students‟ scores. It employed triangulation as the validation strategy using interview and a statistical t-test. The participants of the survey were 151 students while the participants for the experiment were 22 students. The students were the English Letters students of Sanata Dharma University, taking Writing 1 course, or Sentence Writing, in the first semester of the academic year 2013/2014.

xv

discussed in the present study. Further, the results of the open-ended questionnaire and interviews reveal that the application of the CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class enhances the students‟ achievements regarding better grammar understanding, improved sentence writing skill, and improved passage writing ability. The application of the CALL principles in Sentence Writing class is realized through the features and facilities of the web-based class. As the students advantage the class facilities for learning, they experience the CALL principles applied and thus, achieve learning improvement.

xvi ABSTRAK

Yustina Priska Kisnanto. 2014. The Application of Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) Principles in a Web-Based Sentence Writing Class. Yogyakarta: The Graduate Program in English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University.

Dengan perkembangan terkini teknologi komputer dan internet, pembelajaran berbasis web, sebagai salah satu implementasi CALL (Computer-Assisted Language Learning), telah dilihat sebagai cara alternatif baru dalam melayani kebutuhan pembelajaran menulis bahasa kedua. Meskipun demikian, studi-studi deskriptif yang spesifik membahas tentang bagaimana sebaiknya komputer dan teknologi berbasis web harus digunakan untuk memfasilitasi pembelajaran belum sepenuhnya dikembangkan. Hal ini menunjukkan kerangka kerja untuk mengajar dan belajar menggunakan teknologi tersebut perlu dieksplorasi lebih lanjut. Oleh karena itu, penelitian ini bertujuan untuk memverifikasi teori prinsip CALL, yaitu delapan kondisi untuk lingkungan CALL yang optimal oleh Egbert, Chao, dan Hanson-Smith (1999), dalam penerapannya di kelas menulis berbasis web. Hal ini dijabarkan dalam dua objektif penelitian yang berfokus pada (a) menyelidiki intensitas penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL di kelas Sentence Writing yang berbasis web dilihat dari sudut pandang para siswa, (b) menyelidiki apakah penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL di kelas Sentence Writing yang berbasis web meningkatkan prestasi belajar siswa, dan (c) meneliti bagaimana penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL di kelas Sentence Writing yang berbasis web meningkatkan prestasi belajar siswa.

Penelitian ini menggunakan pendekatan penelitian mixed-method, dengan menerapkan survei dan eksperimen sebagai desain penelitiannya. Data penelitian didapat melalui kuesioner, yang terdiri dari item tertutup dan terbuka, wawancara, dan dokumen pengajar berisi nilai-nilai para mahasiswa. Penelitian ini menggunakan triangulasi sebagai strategi validasi berupa wawancara dan uji statistik t-test. Para partisipan survei adalah 151 mahasiswa, sedangkan partisipan untuk eksperimen berjumlah 22 mahasiswa. Partisipan penelitian ini adalah mahasiswa Sastra Inggris di Universitas Sanata Dharma, yang mengambil mata kuliah Writing 1, atau Sentence Writing, pada semester pertama tahun akademik 2013/2014 .

xvii

yang berbasis web. Meskipun demikian, hasil ini tidaklah absolut karena experimen di sini hanya melibatkan satu tritmen tanpa memiliki grup kontrol. Sehingga, ada kemungkinan terdapat faktor lain yang mempengaruhi peningkatan prestasi belajar siswa di kelas Sentence Writing berbasis web ini selain penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL. Adapun faktor-faktor lain yang mungkin mempengaruhi peningkatan tersebut tidak dibahas di penelitian ini. Selanjutnya, hasil kuesioner item terbuka dan wawancara mengungkapkan bahwa penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL di kelas Sentence Writing yang berbasis web ini meningkatkan prestasi siswa dalam pemahaman yang lebih baik akan tata Bahasa Inggris, meningkatkan kemampuan menulis kalimat, dan meningkatkan kemampuan menulis bacaan. Penerapan prinsip-prinsip CALL dalam kelas Sentence Writing diwujudkan melalui fitur dan fasilitas kelas berbasis web ini. Saat siswa memanfaatkan fasilitas kelas untuk belajar, mereka mengalami prinsip CALL yang diterapkan dan dengan demikian, mereka mencapai peningkatan pembelajaran..

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

In this study, I would like to investigate the implementation of a web-based Sentence Writing class for Writing 1 course at university level. Specifically, the study is concerned to explain the Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) principles that the web-based Sentence Writing class apply, seen from the students‟ perspective. Moreover, how the application of the CALL principles of the web-based Sentence Writing class enhances the students‟ writing achievement will be also investigated. This chapter provides readers with an introduction to my study consisting of six sections, i.e. the background to the research, problem identification, problem limitation, statement of the research questions, research objectives, and finally research benefits.

A. Background

Complex skills are involved in writing. In that, L2 writers must “pay attention to higher level of planning and organizing as well as lower level skills of spelling, punctuation, word choice, and so on” (p.303). Indeed, the nature and complexity of writing make the skill not easy to learn.

In catering the L2 writing teaching need, nevertheless, traditional or regular writing class is bounded with limitations. While students need adequate practices for both the micro and macro skills of writing to improve their writing performance, the meeting hours of their writing class schedules seem to be insufficient to accommodate the need. With the advanced development of computer and Internet technologies, the use of these technologies in foreign and second language instructions has significantly expanded (Hubbard & Levy 2006). Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) has been considered as one alternative way of learning, in addition to the traditional education. Particularly, CALL enables teacher-student interactions conducted both synchronously, i.e. in real time communication, and asynchronously, or in a delayed way (Chapelle 2003; Hyland 2003), providing answers to the time and space barrier problems as well as creating more opportunities to expand learning process. Accordingly, more and more language classrooms are now applying CALL, including for teaching writing.

Referring to the advantage of web-based learning, it is not a surprise that there are numerous websites developed to cater the learning of L2 writing. Challenges, however, still exist when implementing a web-based learning. They can be about students‟ computer anxiety, availability of features supporting learning, learning delivery, teacher-student and student-student interactions, or even the class activities. Such challenges thus leave a question on how computer and web-based technologies should best be used to facilitate learning, indicating a framework for teaching and learning using such technologies needs to be explored further.

As a young branch of applied linguistics, the theoretical framework of Computer-Assisted Language Learning is closely related with the Second Language Acquisition (SLA) theories. Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999) derive the eight principles of optimal CALL as in line with the conditions for optimal second language learning environment theories. The eight principles signify that students should be engaged with interaction, authentic audience, authentic tasks, exposure and language production language, enough time and feedback, attention to the learning process, atmosphere with an ideal stress/anxiety level, and finally learner autonomy for optimal results in CALL environments. Accordingly, as one application of CALL, a web-based writing class should ensure the implementation of the computer and Internet technologies be directed to meet the eight principles for optimizing the students‟ learning in writing.

web-based writing class, we will be able to see how the eight conditions are being met and how the implementation leads to optimal learning achievement. For practical implications, it is expected that the results can help L2 writing teachers and educators to evaluate how optimal the use of web for improving students‟ writing learning achievement, identify the learning problems or obstacles students might face in a web-based learning environment they are engaged with, and figure out the specific aspects of a web-based writing class that need improvements. Finally, students will benefit the most. In that, their L2 writing needs can be catered well and eventually, their writing ability will improve.

B. Problem Identification

As a part of CALL applications, research about web-based learning should correspondingly be directed more on the new direction.

Particularly about web-based writing class, a number of experimental studies claim the advantage of web-based writing class over the traditional or regular class in students‟ writing achievements (Al-Abed Al-Haq & Al-Sobh 2010; Chuo 2007; Yang 2004; Al-Jarf 2004; Tsou 2008). However, specific descriptive investigation on the implementation of web-based writing class, i.e. how the web is actually used and meet the CALL principles for optimal learning, is not yet fully developed. Related to the current focus of research in CALL and the gap in web-based writing studies, the necessity of investigating the implementation of a web-based writing class in applying the CALL principles becomes considerably significant.

Two previous studies about ELTGallery were conducted by Kurniawati (2012) and Dameria (2013). While the study by Kurniawati does not provide more detailed information on the use of the web and its implication on students‟ learning in Paragraph Writing class, the second study by Dameria focuses on the learner autonomy, only one aspect of CALL principles, in Sentence Writing class. There is a gap that the present study tries to investigate, that is, the implementation of a web-based Sentence Writing class for Writing 1 course, which uses ELTGallery, in terms of the application of CALL principles and the effect of such implementation in enhancing students‟ learning achievement. In addition, ELTGallery now provides a new feature for students to practice grammar. This grammar practice feature was not yet available in the earlier version of ELTGallery when the previous studies were conducted. The implementation of the new feature, thus, needs to be explored further, especially on how the students advantage the feature to improve their writing skills. In brief, related to the reasons as mentioned above, this study is therefore conducted to investigate the application of CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class and the effect of the implementation on enhancing students‟ writing achievement.

C. Problem Limitation

online is considered as a crucial viewpoint to determine successful implementation of online language learning (Alberth 2010). Related to this, the present study therefore focuses on the Sentence Writing students experiencing the online writing learning to have better insights of the application of the CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class.

According to Chapelle (2001), a CALL evaluation focusing on learners‟ performance should be conducted “through examination of empirical data reflecting learners‟ use of CALL and learning outcomes” (p.54). As this study focusing on the students, the two factors of learners‟ use of CALL and learning outcomes become the main orientations in investigating the optimal implementation of the web-based Sentence Writing class. First, regarding the learners‟ use of CALL, the principles of CALL are addressed. The CALL principles here refer to the eight conditions for optimal CALL by Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999) which involve interaction, authentic audience, authentic tasks, exposure and encouragement to language production, enough time and feedback, attention to the learning process, atmosphere with an ideal stress/anxiety level, and finally learner autonomy. Here, by finding out the application of the CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class according to what the students experience, the intencity and interactions among the principles in the web-based writing class will be clearly identified.

As student achievement deals with the learning done in a particular course (Nation 2009), the students‟ learning achievement used in this study will be based on the course objectives as shown by their writing scores. The writing scores include the students‟ scores of grammar, sentence, and passage writing.

This study is an empirical research which applies a mixed-method research approach. The data were collected through questionnaire, interview, and teacher‟s documentary records of the students‟ writing scores. The study was conducted in the first semester of the 2013/2014 academic year. The participants of this research were the students of the English Letters at Sanata Dharma University, taking Writing 1 course, or Sentence Writing, in the first semester of the academic year 2013/2014. There were 151 students of Sentence Writing in total, who were grouped into four classes, i.e. A, B, C, and D. The students were chosen as the participants of the study because of their experience in learning writing in a web-based Sentence Writing class.

D. Research Questions

This study is focused on answering the following research questions:

1. What CALL principles are reflected in the web-based Sentence Writing class as seen from the students‟ perspective?

2. Does the application of the CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class enhance the students‟ learning achievement?

E. Research Objectives

The integration of computer and Internet technologies into language learning offers an alternative way of teaching communicative language skills, including writing. Since the web-based writing class‟ advantages in outperforming the traditional or regular one are already discussed in many studies, I am interested more to study the actual use of web for teaching. Specifically, this study basically aims at verifying the theory of CALL principles, i.e. the eight conditions for optimal CALL environments by Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999) in a specific classroom applying CALL, i.e. a web-based writing class.

The aim can be elaborated into two objectives. First, as the CALL principles are not applied in isolations, I would like to investigate the application of the CALL principles in a specific web-based writing class, i.e. Sentence Writing class, to see the interactions and intensity of the principles applied in the foundation writing class as experienced by the students. Second, since the implementation of CALL principles can lead to optimal language learning, I would also like to confirm the positive implication, i.e. whether the application of CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class enhances the students‟ achievement as well as investigate further how the application of the CALL principles in the web-based Sentence Writing class enhances the students‟ learning achievement.

F. Research Benefits

achievement may contribute to further development and refinement of current CALL theories and studies, especially improving explanation in terms of web-based writing learning.

12 CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter discusses the theories that support the present study. It consists of two main parts: theoretical review and theoretical framework. The theoretical review explores theories of the principal concepts in this study regarding writing, computer-assisted language learning (CALL) and the principles, teaching writing using web-based technology, web-based sentence writing, and the characteristics of Sentence Writing class‟ students, as well as presents a review of related studies. Meanwhile, the second part of the chapter explains about the theoretical framework underlying the study, synthesized from the whole reviewed theories.

A. Theoretical Review

In this section, theories of the principal concepts in this study will be explored. The theories reviewed concern about writing, CALL and the eight principles of optimal CALL environment, teaching writing using web-based technology, web-based sentence writing class and the features provided by ELTGallery, and the characteristics of the Sentence Writing students. Finally, a review of related studies will be also presented.

1. Writing

teaching L2 writing, sentence writing, passage writing, and student achievement in writing.

a. The Nature of Writing

All of the four skills: reading, listening, speaking, and writing – are needed by learners in order to perform and communicate well in English. According to Harmer (2007: 265), listening and reading are classified as “receptive skills”, the skills “where meaning is extracted from the discourse”, and speaking and writing as “productive skills”, the skills that require students to produce language themselves. The four skills are not done in isolations to employ meaningful communication (Hinkel 2006). In terms of “input and output” (Harmer 2007: 266), for instance, what a learner writes in English is largely influenced by the language input, through what s/he hears or reads in English. In other words, writing can reflect what a learner already knows or acquires (of English). Correspondingly, in order to fully perform a target language learnt, a well-develop writing skill should be obtained.

deliver meaning. Fourth, speakers use pauses and intonation to mark their speech whereas writers use punctuation. Fifth, in terms of production, speakers pronounce while writers spell. Next, speaking is usually spontaneous and unprepared; conversely, most writing takes time, unplanned, and the writers can always „revise‟ what they have written. Also, about the audience‟s response, a speaker speaks to a listener who is (usually) present at the moment of speaking, giving responses such as nodding or frowning, interrupting or questioning; for the writer, in contrast, the reader‟s response can be delayed or absent. Eighth, spoken language is usually informal and repetitive; writing, on the other side, is more formal and compact. Last, while speakers often use simple sentences, writers tend to use more complex sentences with transition words such as „however‟ and „in addition‟.

discourse, and 2) because L2 writers are ultimately evaluated based on their control of language and text construction in their written discourse. This also clarifies how learners‟ L2 writing quality is substantial for it affects their social life and the generalization of their language performance evaluation.

In relation to L2 writing quality, complex skills are involved in order to produce „good‟ writing. In that, L2 writers must “pay attention to higher level of planning and organizing as well as lower level skills of spelling, punctuation, word choice, and so on” (Richards & Renandya 2002: 303). Brown (2004: 221) discusses writing skills specifically classified into micro and macro skills of writing as shown in the following table.

Table 2.1 Micro and macro skills of writing (Brown 2004: 221)

Micro skills Macro skills

Produce grapheme and orthographic patterns of English

Produce writing at an efficient rate of speed to suit the purpose;

Produce an acceptable core of words and use appropriate word order patterns; Use acceptable grammatical systems

(e.g tense, agreement, pluralization patterns and rules);

Express a particular meaning in different grammatical forms; Use cohesive devices in written

discourse

Use the rhetorical forms and conventions of written discourse; Appropriately accomplish the

communicative function of written texts according to form and purpose;

Convey links and connection between events, and communicate such relation as main idea, supporting idea, new information, given information, generalization, and exemplification; Distinguish between literal and implied

meanings when writing;

Correctly convey culturally specific references in the context of the written text;

Develop and use of writing strategies, such accurately assessing the

In order to help students improve their L2 writing quality, it is thus important that they should be taught about both micro and macro skills of writing.

Another thing why writing skill is considered important is because “writing helps students learn” (Raimes, 1983: 3). In that, writing reinforces the language features that have been learnt to learners, gives learners opportunities to explore with the language, and practices their use of eye, hand, and brain in expressing ideas. Here, writing promotes language production and keeps students active physically and cognitively in learning. In brief, in English language teaching, writing is therefore significant for communication purpose, social acceptance, and promoting students in learning a language.

b. L2 Writing Teaching

The complex features of writing as explained in the previous subsection has made teaching the skill seem challenging. Generally, the teaching practices of writing in L2 classrooms are influenced by teacher‟s beliefs and knowledge about writing and teaching writing (Hyland 2003). Respectively, the theoretical and practical knowledge about writing and teaching writing should therefore be cleared out in order to teach the skill more effectively. In relation to this, Hyland (2003) highlights six principal orientations to L2 writing teaching which guide it toward a different focus. They are summarized in the table below.

Table 2.2 The principal orientations to L2 writing teaching (Hyland 2003: 23)

Orientation Emphasis Goals Main pedagogic techniques Structure Language

form

- Grammatical accuracy - Vocabulary

building - L2 proficiency

Function Language Expressivist Writer - Individual

creativity - Self-discovery

Reading, pre-writing, journal writing, multiple drafting, and peer critiques

Process Writer Control of technique

the contexts within which texts are written and read and which make them meaningful (Hyland 2002; 2003).

In addition, as L2 writing students have different needs and characteristics from L1 students (Weigle 2002; Ferris & Hedgcock 2005), determining the best ways to teach L2 writing requires “flexibility” and “support” from the teachers (Hyland 2002: 77). Hyland means that the teachers need to consider the individual instructional context, including the students‟ age, first language background, prior experience, L2 proficiency, writing purposes, target writing communities, and encourage them extensively by providing meaningful contexts, peer participation, prior texts, helpful feedback and control in the writing process. Therefore, in relation to L2 writing teaching orientations mentioned above, a combination, or a “synthesis”, such as by taking the best of the presented approaches, can be done to achieve maximum understanding and learning of writing (Hyland 2003: 26). It means that, in the classroom, teachers should concern not only with how to engage students more with texts and reader expectations, but also supporting them with the knowledge of writing processes, language forms, and genres.

c. Sentence Writing

According to Lock (1996), the word „sentence‟ in written language is defined as “a sequence of structurally related clauses normally begins with a capital letter and ends with a full stop” (p.247). In other words, we can tell if a series of words put together is a sentence or not by examining the structural relation of the words, the capital letter, and the punctuation. This definition also signifies the importance of structure, the use of capital letters and punctuations in writing sentences. According to Harvey (2003), punctuation refers to “the use of signs to help readers understand and express written matter” (p.34). The signs include capital letters, commas, semicolons, colons, dashes, parentheses, and spaces between words. In paragraph writing level, Harvey also states that indented first lines of paragraphs, such as the use of direct or indirect question in the beginning of a paragraph, can also be used to help readers process reading quickly and accurately or as emphasis. Specifically about capital letters, Blass and Gordon (2010) provide several examples of when to use capital letters as follows.

1. For the pronoun I I am from Turkey.

2. For the first letter of the first word of all sentences They work in a school.

3. For the first letter of names, places, languages, and nationalities My name is Abbas. I am from Morocco. I speak Arabic and French.

(Blass & Gordon 2010: 20)

The examples above present the most common situations of using capital letters. Other situations may also require the use of capital letters, such as when dealing with titles of books, magazines, movies, etc, or when using abbreviations.

characteristics” (p.146). The other expressions can take a noun phrase as a subject and different complements, for some verbs require a noun phrase, such as, „Mom baked the cake.‟, and some do not, for example „John fell.‟ (the verbs are italicized). This definition also brings out the classification of a simple and complex sentence. While a simple sentence is a sentence that contains one independent clause (a clause that can stand alone and are not structurally dependent on other clauses), a complex sentence is a sentence that consists of “more than one ranking (i.e. non-embedded or independent) clause” (a clause that is structurally dependent on another clause) (Lock 1996: 247, 261). Take, for example:

(1)You get off at the stop just before the beach.

(2)While it was cooling, they went into the woods in search of sweet honey.

(Lock 1996: 248) The first example is a simple sentence because it only consists of one independent clause (a subject noun phrase „You‟ and a finite verb „get‟). The second example is a complex sentence, containing a dependent clause „While it was cooling,‟ and an independent clause „they went into the woods in search of sweet honey.‟

In relation to the definitions and purposes of a sentence above, a „good‟ sentence should thus meet several criteria. First, a good sentence should be syntactically well-structured. That is, it consists of at least one subject and one verb, agrees with the parts of speech (subject, predicate, object, complement, etc.), as well as corresponds with the structures based on the sentence purpose (a declarative sentence takes the form of a statement, an interrogative sentence takes the form of a question structure, etc). Second, a good sentence should be grammatically acceptable. This includes the rules for verbs (including tenses), subject and verb agreement, the use of articles, etc. Third, a good sentence must be mechanically correct, i.e. using correct punctuation and capital letters. In addition to these criteria, Sadler (2012) defines a good sentence should display clarity. In that, the sentence is understandable for the readers, uses the right words in delivering ideas to the readers, and expresses the writer‟s idea in an interesting way that the readers will enjoy.

d. Passage Writing

The more complex stage than sentence writing will require students to express ideas into sentences and organize them into a paragraph or another simple piece of writing, such as a passage. In written language, „passage‟ can be defined as a smaller excerpt of a written work (Carlin 2013). Thus, in writing a passage of a story, for instance, a writer does not write an entire story. He or she will only write a segment of the whole story, taken from any part of the story. That is why, a passage generally only tells about a specific topic or event. For example, instead of writing about the whole story of a trip, a writer creating a passage can only talk about a particular funny or unforgettable moment during the trip.

paragraphs, topic and support, as well as the cohesion and unity. Another point to concern is grammar. A writer should make the sentences constructing his or her writing are all grammatically acceptable, especially involving the things like the rules of verbs (also tenses), subject-verb agreement, articles, pronouns, etc., to ensure his or ideas are all delivered well and understandable for readers. The eighth aspect is syntax, including the sentence structure and boundaries, stylistic choices, etc. Last, the surface level should also be attended, i.e. the mechanics, which covers the spelling, punctuation, use of capital letters, etc. Indeed, writing a passage is not as simple as it seems to be for it involves so many aspects to consider concerning the writer, the text, and the reader(s).

e. Student Achievement in Writing

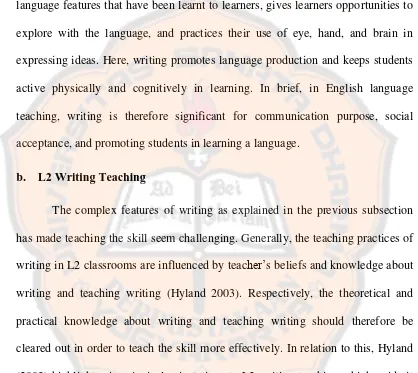

Within a teaching and learning process, students are expected to result in certain learning outcomes. As any types of instructional process are directed by the instructional goals and objectives (Miller, Linn, & Gronlund 2009), the learning outcomes therefore also reflect the objectives. The relationship of learning experience to learning outcomes can be seen in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1. The relationship of learning experience to learning outcomes (Miller, Linn, & Gronlund 2009: 51)

In the figure above, what the students experience in the learning process is about “the knowledge of the specific course content” while objectives refer to “what we expect students to be able to do at the end of instruction”, as stated in terms of learning outcomes (p.51). Indeed, instructional objectives and learning outcomes

Student

Learning

Experience

(Process)

Learning

Outcomes

are closely related as the learning outcomes are directed by the objectives. When perceiving instructional objectives in terms of learning outcomes, Miller, Linn, and Gronlund (2009) add that it is the product of learning that is more concerned rather than the process of learning. Not suggesting that the process is insignificant, they state that the long-term instructional objective is more about the finished product, instead (Miller, Linn, & Gronlund 2009). Thus, as shown in the figure above, in determining students‟ success and effectiveness in learning, we can directly refer to the learning outcomes.

As the result of learning, learning outcomes do represent the learning objectives but cannot visibly tell how successful a student is in learning. It is the student‟s performance which is measurable and observable and indicates his or her learning achievement (Gronlund & Linn 2000). In terms of measurement, Cronbach (1990), as cited in Miller, Linn, & Gronlund (2009: 36), identifies two general categories on the root of the nature of measurement: “measures of maximum performance” and “measures of typical performance”. The first category deals with “a person‟s developed abilities or achievements” while the second category is related to “a person‟s typical behavior” and concerned with “what individuals will do rather that what they can do” (p.36).

the second is developed to signify “degree of success in some past learning activity”. Depending on the purpose, measuring student performance can emphasize on either achievement or aptitude or the combination of both. In short, assessing student achievement is done by measuring student performance which reflects the learning outcomes of what the students have learned as intended by the instructional objectives.

In line with the idea above is Nation (2009) claiming that measures of achievement should focus on how students do learning in a particular course. In other words, assessment of student achievement concerns with the actual performance of students. In that, if we want to determine whether students can perform a task, then we need to assign them perform the task (Gronlund, 2006). Related to writing tasks, for instance, if we want to see whether students can write a story, then we have them write a story.

student achievement. As in the assessment of student achievement in a Sentence Writing class, therefore, it should also cover both tests on the aspects of writing, such as grammar, spelling, and punctuation, and performance tasks, which requires the students to write sentences.

2. Computer-Assisted Language Learning and the Principles

Computer-assisted language learning (CALL) is a relatively young field of study under the applied linguistics domain. The term was first agreed to express the area of technology and second language learning at the 1983 TESOL convention in Toronto (Chapelle 2001). Through explorations and innovations within the field, alternative terms are suggested regularly, such as Technology-enhanced language learning (TELL) by Bush and Terry (1997). The term „CALL‟, though, still becomes the most preferable term to use. In a broad range of practice in the language teaching and learning at the computer, CALL is defined as “any process in which a learner uses a computer and, as a result, improves his or her language” (Beatty 2010: 7). This definition, however, is too restricted to refer to CALL for it does not merely cover the use of computer for enhancing language learning. CALL is a broad field that embraces issues of materials design, (information and communication) technologies, pedagogical theories and modes of instruction (Beatty 2010). Thus, we may refer to CALL to what Levy (1997: 1) defines as “the search for and study of applications of the computer in language teaching and learning.”

Levy (1990), as cited in Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999), points out the need for a theory of CALL that would provide educators with a framework for teaching and learning using computer technologies. Specifically, Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999) signify the importance of a theory of CALL for preparing and evaluating language learning with technology:

Hypothetically, a theory of CALL could assist teachers in making decisions about ways to prepare language learners for the high-technology future they face. ... A theory of CALL could help educators evaluate how and which students learn with different kinds of technology, identify factors that must be addressed in the application of the technology, and serve as a guide for research on language learning.

(Egbert, Chao, & Hanson-Smith 1999: 1)

meaning, authentic audience, authentic tasks, exposure and encouragement to produce varied and creative language, enough time and feedback, attention to the learning process, atmosphere with an ideal stress/anxiety level, and finally learner autonomy.

a. Interaction

Within the computer-mediated communication, interaction can now take the „synchronous‟ or „asynchronous‟ communication forms. Chapelle (2003: 23) states that synchronous communication in learning happens, for example, when learners sit in the computer lab during the course period to read and respond to each other‟s messages discussing a certain topic. With asynchronous communication, she adds, learners can “read/speak and write/hear electronic messages, which are stored on a server to be produced and accessed anytime” (p.23), allowing the process of communication (and learning) can be spread out with unlimited time span (across hours, days, weeks, or even months). In other words, computer-mediated communication expectedly provides more flexible interactions for learners beyond here and now situations.

b. Authentic audience

provide writers with the contexts within which texts are written and read and which make them meaningful.

c. Authentic tasks

The third principle of optimal CALL environments is that learners are involved in authentic tasks. „Tasks‟ often refer to classroom activities similar to those learners will encounter outside the classroom (Chapelle 1999). In language learning, tasks should therefore require learners to use their linguistics resources of the target language to accomplish something (Ellis 2008). From here, authentic tasks are defined as tasks of which goals require (real-world) communication in the target language (Pica, Kanagy, & Falodun 1993, as cited in Chapelle 2003). Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999: 4) also state that authentic tasks should have the same forms of cognitive challenges, or “the thinking required”, as complicated real-world tasks do. They also add that in relation to an optimal CALL environment, it is therefore necessary to design tasks that enable students to use their current proficiency level to function in real-world communications.

d. Opportunities for language exposure and production

The fourth principle is that learners are exposed to and encouraged to produce varied and creative language. Spolsky (1989: 166, as cited in Egbert, Chao, & Hanson-Smith 1999: 5) states that “the outcome of language learning depends in large measure on the amount and kind of exposure to the target language.” From here, Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999) signify that an authentic task alone may not be enough for language acquisition and that encouragement to language production are also needed since “output is also a means to language development” (p.5). Indeed, enhancing the input learners are exposed to (Smith 1993, as cited in Ellis 2008) and encouraging them to produce language (Swain 1985, as cited in Ellis 2008) are important to foster learning.

e. Time and feedback

The fifth principle is that learners have enough time and feedback. Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999) suggest that learners need sufficient time and feedback to cater the formulation of ideas. Within the classroom, learners‟ individual factors may determine the time needed for each learner to finish a task well. Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith see this implying that certain flexibility must be set into the time line for the task so that all learners have the opportunity to reflect on and express their ideas. As computer-mediated communication allows asynchronous communication to take place, CALL applications, such as online learning, would certainly grant the students with time flexibility to work on their tasks. It is the deadlines of task submission, however, that the teacher has to carefully decide to ensure that the students have enough time to formulate ideas and complete their work.

f. Attention to the learning process

The sixth principle of conditions for optimal language learning environments is students are guided to attend mindfully to the learning process. Salomon (1990), as cited in Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999: 6), indicates that to make the best of the learning opportunities given to them, students need to be “mindful” during the learning process; in that, they should be “motivated to take the opportunities” given and to be “cognitively engaged when they perform them”. Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith also state that to cater learning and support cognitive engagement, “a certain degree of metacognitive guidance (instructions and examples about how to learn)” is required (p.6). According to Ellis (2008), metacognitive guidance enables students to “think consciously about how they learn and how successfully they are learning” (p.971).

g. Atmosphere with an ideal stress/anxiety level

The seventh principle is learners work in an atmosphere with an ideal stress/anxiety level. What is meant by “ideal” here is that the appropriate stress/anxiety level of the learning atmosphere in which the students feel comfortable to learn and are still willing to do the learning activities. Experiencing an ideal level of anxiety in the language learning environment is essential to support students‟ comfort, confidence, and motivation before they are engaged and willing to express their ideas (Egbert, Chao, and Hanson-Smith 1999). Promoting students‟ self-confidence is important because as Brown (1994, cited in Johnston 1999) suggested, it is an essential element that determines their success. As with the asynchronous communication form of computer-mediated interaction in CALL applications, students can work on tasks according to their own preferred time and place. Such more relaxed situation is expectedly help students complete tasks more successfully. In addition to this, teacher‟s role is also significant, especially to deal with students‟ “technophobia” or “computer anxiety” (Johnston 1999: 339). As stated by Johnston (1999), teachers can overcome this by establishing, facilitating, and maintaining a pleasing classroom atmosphere, such as by involving the class and making it into a collaborative and cooperative learning situation.

h. Learner autonomy

Chao, and Hanson-Smith (1999: 6), describes a learner-centered classroom as a classroom situation that “develops learners‟ confidence and skills to learn autonomously and to design and coordinate tasks in a variety of contexts.” Here, learners have „freedom‟ in deciding their own learning goals. However, the jobs of creating the boundaries in terms of modeling, mediation, and scaffolding of learning are still in the hands of the teacher as the facilitator.

In a learning environment where students become the center of the learning and teachers as facilitators, such in CALL, learner autonomy is somewhat important for the students to get the most benefit of learning. Autonomous learning, however, cannot be earned in one night. Students need to be initially “directed” to learn independently before moving into a full autonomy. To realize an autonomous learning setting, the teacher-facilitator can advantage the use of technology and thus help students to be more independent in learning. In relation to autonomy and technology, Healy (in Egbert & Hanson-Smith1999: 400-402) suggests four aspects concerning the content and the structure of the learning that a learner must be able to control for realizing autonomy. They are control over time, control over pace, control over the path to the goal, and access to the measurement of success. A learning environment should, therefore, foster such self-learning management for optimal language learning.

anxiety level. In fact, teacher-student and student-student interactions can also create a “space” for language production, while the notion of authentic tasks can determine the amount of language exposure. It should be noted that “the eight conditions act and interact in different ways in different classroom” (Egbert, Chao, & Hanson-Smith 1999: 7). Related to this, studying a specific classroom applying CALL, such as a web-based Sentence Writing class, can be one of the ways to see how the eight conditions are being met.

3. Teaching Writing Using Web-Based Technology

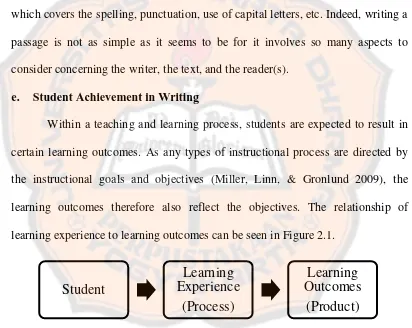

With the expansion of computer technologies in language learning contexts, more and more teachers apply the technologies in teaching communicative skills, including writing. Also with the emergence of word processors, the World Wide Web, e-mails, and Internet, teaching writing advantaging these technologies has been seen as more promising than the traditional classroom. Ferris and Hedgcock (2005) review early studies on computer-assisted writing instructions, presenting both potential benefits and drawbacks, as seen in Table 2.3 below.

Table 2.3 Potential advantages and disadvantages of computer-assisted writing (Ferris & Hedgcock 2005: 347)

Advantages Disadvantages

1. Increased motivation to revise (because of the ease of doing so)

2. Greater consciousness of writing as process

3. Quicker, more fluent, less self-conscious writing

4. Increased writing quantity

5. Increased collaboration (teacher-student and student-student) in the computer writing lab

6. Greater motivation because writing is easier, more interesting, and more enjoyable

1. Increased anxiety due to lack of familiarity with hardware or software 2. Unequal or limited student access to

computers

3. Limited student typing and/ or word processing abilities

4. Subversion of individual student writing processes (some prefer pen and paper; some are distracted by writing in a lab setting)

(Teichman & Poris, 1989, p.93) (Balestri, 1998; Barker, 1987;

Bernhardt et al, 1989, 1990; Bridwell-Bowles et al., 1987; Haas 1989; Hawisher, 1987)

The evidence shows that computer use in teaching writing is potentially strong in improving students‟ attitudes, confidence, and motivation, the aspects which are mostly essential for L2 learners to master writing successfully. The potential disadvantages as shown in the table above, though, should provide teachers with the aspects to consider in finding the strategies to answer the challenges of implementing computer-assisted learning for writing.

Advantaging the computer-mediated communication and the World Wide Web, a writing class with the Web delivery system or web-based writing class has the benefit of more flexible interactions, including the teacher-student and student-student interactions. In that, writing can take place synchronously, i.e. where students communicate in real time via discussion software on Local Area Networks or Internet chat sites with all participants at their computers at the same time, as well as asynchronously, that is, where students communicate in a delayed way, such as via email (Hyland 2003). This characteristic provides more opportunities for teacher and students to interact and collaborate in learning, especially to give and get helps and feedbacks. The advantage of web-based writing class is therefore considered as capable of countering the potential problems of computer-assisted writing that may occur.

conferences, and peer response sessions, but carrying out the rest of the course outside a classroom. They also add that the teacher may post all course materials, such as syllabus, assignments, worksheets, exercises, presentations of material, on the course Web site and interacts with students through e-mail, discussion lists, real-time chats, and online conferencing. Moreover, teachers can create a “paperless class” using electronic portfolio for submissions (p.361). In other words, students are more engaged with online mediated tasks rather than face-to-face interactions.

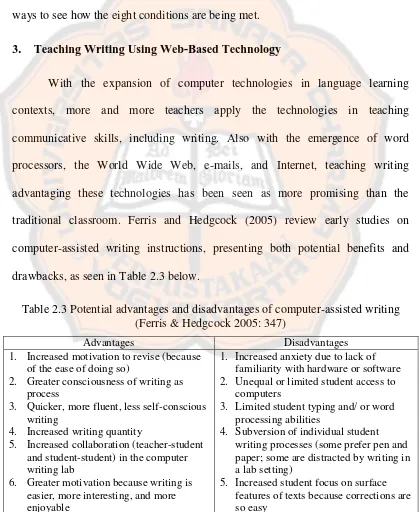

4. Web-Based Sentence Writing Class

In order to get a clearer picture of the web-based Sentence Writing class discussed in the present study, this subsection provides readers with explanations of what the course is about as well as the teaching and learning activities. Using the ELTGallery website in the learning process, the features offered by the website will be also explained one by one.

a. Sentence Writing Class

WRITING 1 1. Credit : 1

2. Description : This course aims to help the students to develop their ability to write grammatically acceptable sentences and to write simple passages 3. General Objectives :

1 The students are able to write sentences with complete sentence elements (subject, predicate, and other necessary elements).

Sentence 1

2 The students are able to write sentences with a correct choice of tense. Assignment 1: The students are to write a short passage about

themselves (personal identity, family, high school, and hometown).

Tense 1

3 The students are able to write sentences with a correct article determiner before a common noun. Peer evaluation: the students are to evaluate their classmates‟ passage on their biography.

Article and Deterniner

1

4 The students are able to write sentences with a correct from personal pronouns. Assignment 2: the students are to write an unforgettable experience which they had.

Personal Pronoun

1

5 The students are able to write verbal (yes/no) and pronominal (wh-word) questions. Peer

evaluation: the students are to evaluate their classmates‟ passage on unforgettable experiences.

Question 1

6 The students are able to write sentences with noun phrases which contain two or more modifiers.

Noun Modification

1

7 The students are able to write sentences with correct auxiliary verbs. Peer evaluation: the students are to evaluate their classmates‟ passage on college life.

Auxiliary Verb 1

8 The students evaluate their progress in the first half of the semester according to the work they have done and their classmates‟ evaluation and set the grade they deserve to get based on the

evaluation.

Mid-Term 1

9 The students are able to write sentences in the perfect and progressive (continuous) aspects. Assignment 4: the students are to write about their ideal figure of wife, teacher, lecturer, politician, doctor, or any other occupation).

Perfect & Continuous