Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:56

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Level of Total Quality Management Adoption in

Qatari Educational Institutions: Private and

Semi-Government Sector

Noor Fauziah Sulaiman , Nick-Naser Manochehri & Rajab Abdulla Al-Esmail

To cite this article: Noor Fauziah Sulaiman , Nick-Naser Manochehri & Rajab Abdulla Al-Esmail (2013) Level of Total Quality Management Adoption in Qatari Educational Institutions: Private and Semi-Government Sector, Journal of Education for Business, 88:2, 76-87, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.649311

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.649311

Published online: 04 Dec 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 148

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.649311

Level of Total Quality Management Adoption

in Qatari Educational Institutions: Private

and Semi-Government Sector

Noor Fauziah Sulaiman

Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Nick-Naser Manochehri

Community College of Qatar; and Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Rajab Abdulla Al-Esmail

Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

The authors evaluated the level of Total Quality Management (TQM) adoption in Qatari educational institutions within private and semigovernment institutions. To accomplish these objectives, a literature review was done of TQM adoption in higher education institutions, followed by a survey questionnaire. Data were collected from Qatari educational institutions with SPSS used in performing the analysis. It assessed awareness, understanding, benefits, and progress of TQM implementation based on the 11 critical success factors (CSFs) or essential elements developed in the revisited model of leverage points for a total quality culture transformation. The strongest driving force toward TQM was teamwork while the strongest restraining force was lack of knowledge of TQM principles and its associated tools. The analysis concluded that although there was a low level of TQM implementation, the dominant perception of TQM in general was positive where a culture toward collective consciousness or teamwork was beginning to be accepted within private and semigovernment educational institutions in Qatar. The findings would be of a particular interest to private and public educational institutions; especially those that intend to initiate TQM and accreditation within their institutions in the Middle East.

Keywords: educational institution, Middle East, Qatar, quality culture, TQM adoption

INTRODUCTION

The future of the industry depends on how successfully it adapts to change and, more proactively, how it creatively changes to its own advantage. Consequently, the drivers for change have influenced the way day-to-day business is carried out in academic institutions and many of these institutions began to adopt Total Quality Management (TQM; Bolton, 1995; Hides, Davis, & Jackson, 2004; Sahney, Banwet, & Karunes, 2004a; Yeo 2008). TQM offers

Correspondence should be addressed to Nick-Naser Manochehri, Community College of Qatar, P.O. Box 63211, Doha, Qatar. E-mail: [email protected]

increased quality and efficiency, less waste, higher pro-ductivity, enhanced customer satisfaction, and an improved image of educational institutions (Biehl, 1999; Hides et al.; Hwarng & Teo, 2001; McCormick, 1993; Singh, Grover, & Kumar, 2008).

Brookes and Becket (2007) reviewed TQM issues and practices throughout higher education (HE) environments across the globe in three key geographic areas: the Americas; Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA); and Asia Pacific between 1996 and 2006 in 34 countries. Their study catego-rized environmental forces for change into three groupings (Table 1).

Particularly for the EMEA region, Brookes and Becket (2007) noted the drivers for quality provision were consider-able changes regarding sources and level of funding due to

TABLE 1

Environmental Forces for Change

Political forces

Government initiatives to widen access

Government development of more higher education institutions (HEIs) Strict governmental control over HE curriculum and management No unified or centralized system for government control

Economic forces

Reduced or limited funding per student Reliance on private sector funding

Reliance on tuition or international student fees Rising costs per student

Increase in number of private HEIs Greater emphasis on internationalization

Sociocultural forces

Greater demand for student places Greater diversity of student populations Greater diversity of provision

Consumer pressure for greater accountability or value for money

the increasing number of private institutions or the reliance on private sector funding, a commonality in terms of govern-ment initiatives to increase access to HE, and a significantly diversified student market as a result. In short, motivated by competition, costs, accountability, and service orientation some educational institutions had begun to embrace TQM (Koslowski, 2006).

Thus, motivations or reasons why organizations have tried to implement total quality can be categorized as either from the external motivation (the need to adapt the organization to the changing external environment) or internal motivations (the need to integrate the organization’s members internally to fulfil its role).

THE IMPORTANCE OF TQM AS A STRATEGIC ISSUE FOR QATARI EDUCATIONAL

INSTITUTIONS

Information technology, which has replaced national economies with a global economy, is such that countries that do not practice TQM have become globally non-competitive. Globalization has placed increasing pressure on Qatar, as a developing country, to focus and raise its education system and skills level toward a more qualified workforce, as documented by the Supreme Education Council of Qatar “Education for a New Era” (Supreme Education Council of Qatar, 2009), and by the State of Qatar’s Qatarization policy (Qatarization, 2009), which aims to increase the percentage of Qatari citizens in the workforce. In addition, Qatar’s Vision 2030 has placed even greater importance on the education sector as a major driver for turning Qatar into a knowledge-based economy due to its current investment policy in the non-energy sector (World Bank, 2007).

The potential benefits of TQM in educational institutions are quite apparent. TQM can help a school or college pro-vide better service to its primary customers, students, and employers. In addition, the continuous improvement focus of TQM is a fundamental way of ensuring accountability requirements common to educational reform.

Since 2001, the reform of public education in K–12 has made rapid progress incorporating curriculum standards that strives to meet international benchmarks through the estab-lishment of autonomous schools (semi-government primary and secondary independent school) that foster creativity and critical thinking, and the development of evaluation tools that provide the ability to report and track school progress. At the university level, Qatar University (the only state univer-sity in Qatar), has focused on raising its standards through varied approaches such as the establishment of the Qatar University Reform Plan (Attiyah & Khalifa, 2009; Al-Azmeh 2006) to develop its mission and vision and to review its organizational objectives, governance structures, and roles (e.g., to continually improve the quality of instructional and educational services, and promote administrative efficiency such as self-assessment of corporate identity program and in-ternational accreditations). Additionally, six American uni-versities were established at the Education City in Doha to enhance domestic capabilities in HE without the associated infrastructure costs and to support academically able students to study at world-class universities for the preparation of a knowledge-based society.

The present scenario emphasizes the importance of TQM principles in the Qatari education system. However, literature has indicated that educational institutions have been lagging behind other organizations in their Total Quality culture (TQ culture; Bolton, 1995; Singh et al., 2008; Sirvanci, 2004). An organization with a total quality culture is an organization that has a clear set of values and beliefs that foster total quality behavior. Kanji and Yui (1997) described it as:

[The] culture of an organization committed to customer satis-faction through continuous improvement. This culture varies both from one country to another and between different in-dustries, but has certain essential principles which can be implemented to secure greater market share, increased prof-its and reduced cost. (p. 417)

Because culture emerges as a response to internal and exter-nal problems, members of organization must learn to adapt; changing a culture from the traditional to a TQ culture re-quires learning. People must come to a new understanding of what quality means. For a TQM organization, this learning is ongoing as the organization continuously seeks to improve customer value.

Unfortunately, there is limited literature emphasizing the adoption of TQM values and philosophy in Qatar (Al-Attiyah & Khalifa, 2009; Al-Khalifa & Aspinwall, 2000, 2001; Salaheldin, 2009; Salaheldin & Zain, 2007), especially in an

Necessary management

behaviour Strategy for TQM

implementation

Training, education & development

Organisation for TQM

Process Management

& system

Teamwork Employee

involvement & empowerment

Partnering Communication

for TQM Recognition & reward

Quality technologies

New culture

Old culture Old

culture Old

culture

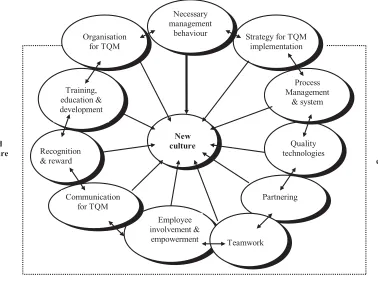

FIGURE 1 Leverage points for a total quality culture transformation. Adapted from Bounds, Yorks, Adams, and Ranney (1994, p. 491) and Sulaiman (2002, p. 183).

educational context. Only Al-Khalifa and Aspinwall investi-gated more comprehensively the culture of Qatar industries about a decade ago. Their conclusion suggested that Qatar companies would find difficulties in implementing TQM because they are dominated by a rational and hierarchical culture. Responding to this need, this study provides much needed present information on the state of TQ culture within the Qatari educational context because it was seen as cru-cial to implementing quality programs (Davies, Douglas, & Douglas, 2007). Also, a solid understanding of culture in-forms managers about how to change behavior in order to embed TQM. Many organizations have no clear idea of the progress they have made or how far they still have to go to achieve quality (Evans, 2007; Evans & Lindsay, 2008; Lascelles & Dale 1993). Given such evidence, this preliminary study will shed light on the level of TQM adoption and the emerging culture in Qatari educational institutions.

CONTEXT OF THE STUDY

The formation and application of standardized models of quality systems and TQM was formed in late 1970s. TQM models, based on the teachings of quality gurus or interna-tional quality awards, generally involve a number of essential

elements or “correct environment” that has been described by some researchers (Evans, 2007; Fryer, Antony, & Douglas, 2007; Kanji & Yui, 1997; Kanji, Tambi, & Wallace, 1999; Singh et al., 2008) as the critical success factors (CSFs) that are required for successful TQM implementation. Thus, we attempted to evaluate the progress of TQM implementation in Qatari educational institutions based on 11 CSFs or es-sential elements developed in the revisited Model of Lever-age Points for a TQ Culture Transformation developed by Sulaiman (2002). The CSFs for TQM were identified through an extensive literature survey (Berry, 1991; Ghobadian & Speller, 1994; Porter & Parker, 1993).

In an earlier study, Quazi et al. (1998) highlighted that managers could use CSFs to evaluate the perceptions of quality management in their organization as well to assist decision makers in identifying those areas of quality man-agement where improvements should be made. The 11 CSFs that influence TQM implementation in education are interre-lated and reinforce each other (Figure 1): necessary manage-ment behavior, strategy for TQM implemanage-mentation, education and training, organization for TQM, process management and systems, employee involvement, teamwork, partnering, communication for TQM, recognition and reward, and qual-ity technologies (tools and techniques). These CSFs present to act as a guide for higher education contemplating a TQM initiative.

In order to improve TQM adoption as well as TQM im-plementation within the educational institutions, managers in educational institutions need to challenge old assump-tions about their business through learning (Srikanthan & Dalrymple, 2002, 2004; Sulaiman, 2002), particularly when contemplating the real meaning of quality in education and to accept new roles and responsibilities for accomplishing continuous improvement throughout their organizations and within the educational system. In addition, the general academic culture that is considered suitable for TQM that emerges from the literature appears to be one that pursues collective consciousness (Srikanthan & Dalrymple, 2002, 2004), cooperation and support (Davies et al., 2007), or teamwork.

PROBLEMS WITH IMPLEMENTING TQM IN EDUCATION

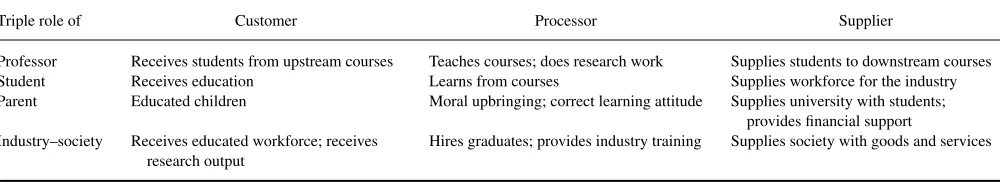

As discussed previously, without a conducive environment that is required for successful TQM implementation, TQ cul-ture will be difficult to grow. The industry’s wide spectrum of activities and the multiple roles of the multiple stakehold-ers with divstakehold-erse or even contradictory demands in education systems (Eagle & Brennan, 2007; Fryer et al., 2007; Hwarng & Teo, 2001; Sirvanci, 2004) have often led to lack of clarity about the purpose of the institution as well as role ambiguity toward quality objectives. For example, if looking at the role of students in higher education institutions (HEI), Sirvanci (2004) regarded students as having multiple roles and that is why customer identification in HE remains a complicated issue. When students are seen as the product in process role, the hard elements such as student learning results will be critical. Thus, HE is expected to improve its products (i.e., students) and provide services even if students would prefer to avoid (e.g., foundation courses) and modify them rather than satisfy their needs (Bolton, 1995). When students re-ceive service (knowledge) from their instructors, they are seen as the laborers in the learning process role and are ex-pected simultaneously to work and exert effort in order to learn the material by various means of hard elements such

as completing projects, term papers, and preparing for tests. However, to be successful in this role, students need the nec-essary of elements such as skills, disposition, and motivation. Thus, the interplay of students’ role above has further emphasized the importance of bridging the hard and soft elements of culture for TQ culture transformation. Without purposeful responsibilities to ensure total adoption of the CSFs, successful implementation of TQM will be difficult (Atkinson, 1990; Lascelles & Dale 1993). In this case, Juran and Gryna’s (1982) triple role concept that every activity has a triple role of customer, processor, and supplier will not only facilitate the identification of the various customers in educa-tion institueduca-tions but also help explain the roles played by the different stakeholder groups (Hwarng & Teo, 2001). Hwarng and Teo emphasized that educational institutions have to re-alize that they are in the business to satisfy many parties (see Table 2 for an example in HE) and that it is important to identify all customer groups and address their concerns. The importance of system modeling approach and stakeholders’ approach to help understand organizational performance or TQ culture transformation were also highlighted in Kanji’s Performance Measurement System (Kanji, n.d.).

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

In order to determine the level of TQM adoption in Qatari ed-ucational institutions, the following research questions were developed:

Research Question 1: What are the levels of awareness and understanding on the meaning of quality and TQM within the academic institutions in Qatar?

Research Question 2: What are the benefits that promote the adoption or implementation of TQM within the aca-demic institutions in Qatar?

Research Question 3: What are the problems that inhibit the adoption or implementation of TQM within the aca-demic institutions in Qatar?

Research Question 4:What are the most important issues related to TQM initiative efforts within the academic institutions in Qatar?

TABLE 2

Example of Triple Roles of Customer, Processor, and Supplier in Higher Education

Triple role of Customer Processor Supplier

Professor Receives students from upstream courses Teaches courses; does research work Supplies students to downstream courses Student Receives education Learns from courses Supplies workforce for the industry Parent Educated children Moral upbringing; correct learning attitude Supplies university with students;

provides financial support Industry–society Receives educated workforce; receives

research output

Hires graduates; provides industry training Supplies society with goods and services

Source:Hwarng & Teo, 2001

METHODOLOGY

To answer the research questions, a survey was developed. The survey was adapted from Sulaiman (2002), and consisted of five parts: the general profile of the respondents and their institutions, their understanding on quality and TQM princi-ples, benefits gained from implementing TQM and quality initiatives, obstacles and reasons for not implementing TQM and quality initiatives, and their opinion on the CSFs which influence TQM implementation.

Data Processing

Data were processed using SPSS for Windows version 13.0. Descriptive statistics were used to define the profile of the sample, to explore respondents’ perception on their under-standing on quality and TQM principles, and the obstacles and reasons for not implementing TQM–quality initiatives. To explore respondents’ perception on benefits gained from implementing TQM–quality initiatives and their opinion on the CSFs that influence TQM implementation, analyses were carried out with statistical mean ranking, cross tabulation and analysis of variance (ANOVA). The analyses deal mainly with ranking of the variables based on their mean values and by ANOVAF statistics to test the null hypothesis that the mean values of the dependent variable are equal for all groups. A cutoff value ofp <.05 (or 5% significant level)

was used to distinguish between converging and diverging views.

Reliability Analysis

The purpose of a reliability analysis is to determine how consistently the selected variables measure some construct. Reliability analysis on questionnaire scores was done using Cronbach’s coefficient alpha to estimate consistency of the scores from the questionnaire. Values of alpha range between 0 and 1.0, with higher score values indicating higher reliabil-ity. The reliability of the entire constructs measured by each statement on the scale of 1 to 5 was computed. The alpha value for statements relate to TQM environment, TQM ben-efits, and TQM important issues were .901, .911, and .865, respectively. Furthermore, the statements related to CSFs for TQ culture were categorized into 11 and the alpha value was .904. Thus, the alpha values range from .865 to .917, which are above the threshold value of .70 and indicates an internal consistency and reliable measure of the construct (Hill & Lewicki, 2006; Nunnaly, 1978; Pallant, 2001).

Survey Administration

The intended survey respondent were principals, academic principals, and instructors of educational institutions in Qatar from private and semigovernment institutions. Respondents were informed that the survey was entirely voluntary and all responses would remain strictly confidential and were for

research purposes only. A pilot study was first conducted to assess the questionnaire. Following the pilot, changes were made to improve readability and thereby reduce the amount of time to answer the survey. Content validity was established through a review of questionnaire by some faculty members.

Of the 100 questionnaires distributed to a random stratified sample of academics from 37 educational institutions, 54 were returned and some of the responses were from the same educational institution. Three people missed significant parts of the survey (i.e., TQM benefits, obstacle, or CSF questions) and had to be eliminated. As a result, the number of valid questionnaires was 51 representing a response rate of 51%.

RESULTS

Background Information

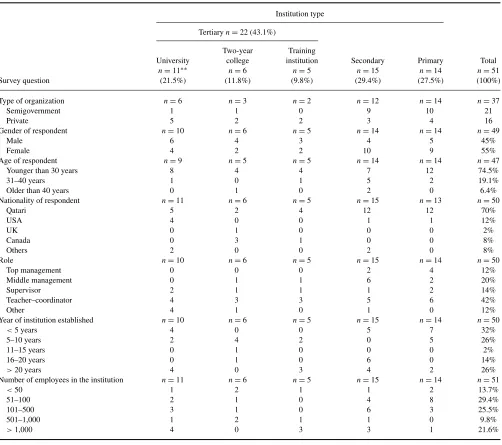

The characteristics of an organization can affect the imple-mentation of TQM. The characteristics of the sample are set out in Table 3. Atkinson (1990) stated that “organiza-tions employ differing technology, have different histories and backgrounds, serve different markets with different prod-ucts and employ people from different cultures, so the drive to improve quality has to be managed differently” (p. 398).

The majority of the respondents were from secondary (29.4%) and primary (27.5%) schools. For the purpose of analysis, the university (21.6%), two-year college (11.8%), and training institution (9.8%), will be grouped as tertiary or HEI (43.1%). The majority of the respondents were hold-ing a role of teacher–coordinator (42%). Of the 51 usable responses 55% were women, 45% were men, and 70% of them were Qatari. A large percentage of respondents (74.5%) were aged below 30 years because the majority working age population in Qatar is between 25 and 29 years old (Qatar Statistics Authority, 2009). This indicates that a young work-force will accept change quicker than old workwork-force, as an old workforce may feel threatened at having to learn new responsibilities and use new work methods (Mann & Kehoe, 1995).

The Levels of Awareness and Understanding on the Meaning of Quality–TQM.

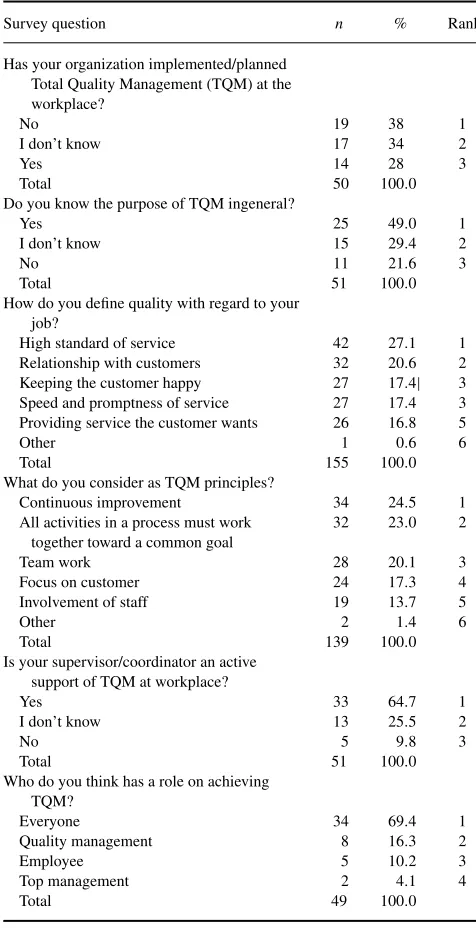

Table 4 shows the results of awareness and understanding of quality–TQM in general by respondents of the survey. It shows a relatively low level of TQM implementation (28%) within the educational institutions in Qatar. However, there is a moderate degree of awareness–understanding of the pur-pose of TQM (49%) and some promising development of awareness–understanding of the principles of quality–TQM within the educational institutions in Qatar.

When they were asked “How do you define quality with regard to your job?” the total respondents ranked high stan-dard of service, relationship with customer, keeping the

TABLE 3

General Profile of Respondents According to Institutions

Institution type

Tertiaryn=22 (43.1%)

Two-year Training

University college institution Secondary Primary Total n=11∗∗ n=6 n=5 n=15 n=14 n=51

Survey question (21.5%) (11.8%) (9.8%) (29.4%) (27.5%) (100%)

Type of organization n=6 n=3 n=2 n=12 n=14 n=37

Semigovernment 1 1 0 9 10 21

Private 5 2 2 3 4 16

Gender of respondent n=10 n=6 n=5 n=14 n=14 n=49

Male 6 4 3 4 5 45%

Female 4 2 2 10 9 55%

Age of respondent n=9 n=5 n=5 n=14 n=14 n=47

Younger than 30 years 8 4 4 7 12 74.5%

31–40 years 1 0 1 5 2 19.1%

Older than 40 years 0 1 0 2 0 6.4%

Nationality of respondent n=11 n=6 n=5 n=15 n=13 n=50

Qatari 5 2 4 12 12 70%

USA 4 0 0 1 1 12%

UK 0 1 0 0 0 2%

Canada 0 3 1 0 0 8%

Others 2 0 0 2 0 8%

Role n=10 n=6 n=5 n=15 n=14 n=50

Top management 0 0 0 2 4 12%

Middle management 0 1 1 6 2 20%

Supervisor 2 1 1 1 2 14%

Teacher–coordinator 4 3 3 5 6 42%

Other 4 1 0 1 0 12%

Year of institution established n=10 n=6 n=5 n=15 n=14 n=50

<5 years 4 0 0 5 7 32%

5–10 years 2 4 2 0 5 26%

11–15 years 0 1 0 0 0 2%

16–20 years 0 1 0 6 0 14%

>20 years 4 0 3 4 2 26%

Number of employees in the institution n=11 n=6 n=5 n=15 n=14 n=51

<50 1 2 1 1 2 13.7%

51–100 2 1 0 4 8 29.4%

101–500 3 1 0 6 3 25.5%

501–1,000 1 2 1 1 0 9.8%

>1,000 4 0 3 3 1 21.6%

Note.Some primary and secondary schools had more than one branch. Some universities, colleges, and institutions had been surveyed few times because they had many colleges within.

customer happy, and speed and promptness of service as the first three most important definitions of the meaning of qual-ity to their business respectively. Here, results show that although the emphasis is more toward the hard or tangible aspects of quality such as high standard of service that is usu-ally measured through accreditation process, the soft or in-tangible aspects of quality such as relationship with customer and keeping the customer happy is beginning to surface. It was also noticed that the results confirmed the perception that most educators would rather modify than satisfy the needs of their customer (students) because most respondents ranked providing service the customer wants as fifth.

A promising development was shown by more respon-dents (69.4%) agreeing that everyone should be responsible or has a role on achieving TQM. Conversely, only (16.3%) perceived that it’s the job of quality management and only (4.1%) perceived it’s the job of top management, which fur-ther emphasizes that the majority of respondents do under-stand that quality should not be seen as a supervisory matter (Atkinson, 1990) though the ultimate responsibility lies with management (Koslowski, 2006).

Another promising development was that (64.7%) per-ceived their supervisor–coordinator as an active support of TQM at workplace. As noted previously, managerial

TABLE 4

The Awareness and Understanding of Quality–Total Quality Management in General of Total Respondents

Survey question n % Rank

Has your organization implemented/planned Total Quality Management (TQM) at the workplace?

No 19 38 1

I don’t know 17 34 2

Yes 14 28 3

Total 50 100.0

Do you know the purpose of TQM ingeneral?

Yes 25 49.0 1

I don’t know 15 29.4 2

No 11 21.6 3

Total 51 100.0

How do you define quality with regard to your job?

High standard of service 42 27.1 1 Relationship with customers 32 20.6 2 Keeping the customer happy 27 17.4| 3 Speed and promptness of service 27 17.4 3 Providing service the customer wants 26 16.8 5

Other 1 0.6 6

Total 155 100.0

What do you consider as TQM principles?

Continuous improvement 34 24.5 1

All activities in a process must work together toward a common goal

32 23.0 2

Team work 28 20.1 3

Focus on customer 24 17.3 4

Involvement of staff 19 13.7 5

Other 2 1.4 6

Total 139 100.0

Is your supervisor/coordinator an active support of TQM at workplace?

Yes 33 64.7 1

I don’t know 13 25.5 2

No 5 9.8 3

Total 51 100.0

Who do you think has a role on achieving TQM?

Everyone 34 69.4 1

Quality management 8 16.3 2

Employee 5 10.2 3

Top management 2 4.1 4

Total 49 100.0

Note.Some respondents choose more than one answer or did not answer.

subculture is the key to inducing a paradigm shift. It de-termines the culture of the rest of the organization. Managers have the power and authority to determine the organizational strategy, systems, policies, and operating procedures. If man-agement does not understand the total quality concept, then their influences on the behavior of employees and the level of support for quality issues and improvements programs may be detrimental (Atkinson, 1990; Bolton, 1995; Sirvanci, 2004).

When a cross tabulation was constructed and respondents were classified into institutional levels (Table 5), it was fur-ther established that respondents from the primary

institu-tions seem to have implemented or planned TQM better (about 43% responded “Yes” while 36% responded “No”) and showed a higher percentage or better awareness and understanding of TQM in terms of knowing the purpose of TQM (64% responding “Yes” and 7% “No”) compared to the secondary (40% responding “Yes” and 27% responding “No”) and tertiary institutions (46% responding “Yes” and 27% responding “No”). Also, respondents from the primary institutions had the highest percentage of respondents who perceived that everyone was responsible for TQM–quality (78.6%). However, respondents from secondary institutions had the highest percentage of respondents who perceived their supervisor/coordinator as an active support of TQM (73.3%).

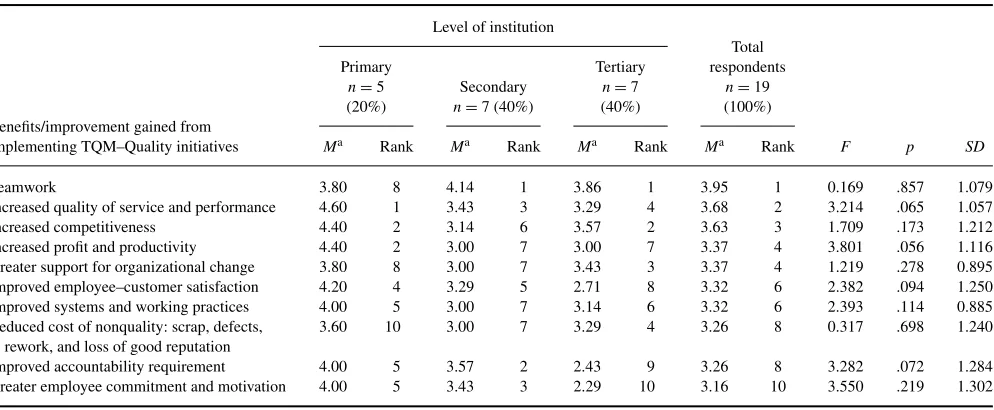

Benefits and Improvement Gained From Implementing TQM–Quality Initiatives

Table 6 shows perceptions on a set of major benefits gained from the implementation of TQM–quality initia-tives answered by respondents from institutions that have implemented/planned TQM. The ANOVA analysis indicated that there was no statistically significant difference of views (as shown in the p column) between the three different levels of institutions.

Table 5 shows that, in general, total respondents from insti-tutions that implemented/planned TQM, do not believe that their institution gained any extensive benefits or improve-ment from impleimprove-menting TQM–quality initiatives at work-place (Ms< 4) because they may still be in their infancy

stage of TQM implementation or still getting used to the idea of TQM as shown in Table 5 where only (49%) of total respondents knew the purpose of TQM. The highest ratings given by the total respondents were teamwork (M=3.95), increased quality of service and performance (M=3.68), and increased competitiveness (M =3.63). These findings sup-port the literature review on the drivers for change or reasons why educational institutions decided to develop their quality initiatives and implement TQM. Also, findings demonstrated promising development in terms of the effect TQM on the Qatari academic culture, especially on teamwork.

Other interesting observations were that greater employee commitment and motivation were ranked as the least benefits and improvement gained from implementing TQM–quality initiatives by the total respondents from institutions that im-plemented and planned TQM (M =3.16). These findings agreed with Wilkinson, Redman, and Snape (1994) that “cul-tural changes are unlikely to occur simply by a ‘quick fix’ approach to improving employee awareness” (p. 401). It also agreed with Al-Khalifa and Aspinwall (2000), who studied the development of TQM in Qatar that cited culture change as a major problem. Only tertiary institutions ranked greater support for organizational change within their first three most important benefits. Suspicion and resistance, which are more related to the soft element of culture, were the most common

TABLE 5

The Awareness and Understanding of TQM in General According to Institutions

Level of institution

Primary Secondary Tertiary Total percent

Survey question n=14 (27.5%)a n=15 (29.4%)a n=22 (43.1%)a responsesn=51 (100%)a

Implemented/planned TQM

Yes 6(42.9%)b 2(14.3%)b 6(27.3%)b 14(28%)a

No 5(35.7%)b 8(57.1%)b 6(27.3%)b 19(38%)a

I don’t know 3 4 10 17

Total responses n=14 n=14 n=22 n=50 (100%)

Do you know the purpose of TQM?

Yes 9 (64.3%)b 6 (40.0%)b 10 (45.5%)b 25 (49%)a

No 1 (7.1%)b 4 (26.7%)b 6 (27.3%)b 11 (21.6%)a

I don’t know 4 5 6 15

Total responses n=14 n=15 n=22 n=51 (100%)

Responsible for TQM–Quality

Everyone 11 (78.6%)b 9 (60%)b 14 (70%)b 34 (69.4%)a

Quality management 2 2 4 8

Employee 0 4 1 5

Top management 1 0 1 2

Total responses n=14 n=15 n=20 n=49

Supervisor/coordinator as an active support of TQM

Yes 9 (64.3%)b 11 (73.3%)b 13 (59.1%)b 33 (64.7%)a

No 1 (7.1%)b 1 (6.7%)b 3 (13.6%)b 5 (9.8%)a

I don’t know 4 3 6 13

Total responses n=14 n=15 n=22 n=51 (100%)

a% of total respondents.b% within educational level.

reaction to new paradigm and perhaps less easy to be achieved, especially when many elements of academic cul-ture were not receptive to TQM (Koch, 2003). For exam-ple, despite respondents from primary institutions seeming

to feel more benefits and improvement gained (mostMs>

4) from implementing TQM–quality initiatives than other groups. Furthermore, they ranked teamwork and greater sup-port for organizational change as the second least benefits

TABLE 6

Analyses of Variance and Mean Ranking for Perceived Benefits/Improvement Gained From Implementing Total Quality Management (TGM)–Quality Initiatives According to Level of Institutions

Level of institution

Total

Primary Tertiary respondents

n=5 Secondary n=7 n=19

(20%) n=7 (40%) (40%) (100%)

Benefits/improvement gained from

implementing TQM–Quality initiatives Ma Rank Ma Rank Ma Rank Ma Rank F p SD

Teamwork 3.80 8 4.14 1 3.86 1 3.95 1 0.169 .857 1.079

Increased quality of service and performance 4.60 1 3.43 3 3.29 4 3.68 2 3.214 .065 1.057

Increased competitiveness 4.40 2 3.14 6 3.57 2 3.63 3 1.709 .173 1.212

Increased profit and productivity 4.40 2 3.00 7 3.00 7 3.37 4 3.801 .056 1.116

Greater support for organizational change 3.80 8 3.00 7 3.43 3 3.37 4 1.219 .278 0.895 Improved employee–customer satisfaction 4.20 4 3.29 5 2.71 8 3.32 6 2.382 .094 1.250 Improved systems and working practices 4.00 5 3.00 7 3.14 6 3.32 6 2.393 .114 0.885 Reduced cost of nonquality: scrap, defects,

rework, and loss of good reputation

3.60 10 3.00 7 3.29 4 3.26 8 0.317 .698 1.240

Improved accountability requirement 4.00 5 3.57 2 2.43 9 3.26 8 3.282 .072 1.284 Greater employee commitment and motivation 4.00 5 3.43 3 2.29 10 3.16 10 3.550 .219 1.302

a1=not at all, 2=limited, 3=regularly, 4=extensively, 5=to a great extend.

TABLE 7

Total Respondents Views on 20 Statements That Relate to the 11 Critical Success Factors Influencing the Environment for Total Quality Culture

Agreed to some extent (total respondents:M>3.50)a Disagreed to some extent (total respondents:M<3.50)b

My supervisor can help me to do my job better. There is much friction between groups and departments. My decisions are based on analysis of data and information. Everybody in the institution understands the total quality concept. Our use of team processes leads to increase morale. I have received on-going training to do my job right the first time. We address problems through prevention and continuously improving all My company is committed to TQM.

processes. There is a very strong trust between management and workers.

I receive recognition for top quality job done. We are treated fairly and get recognition for what we do.

I am provided with proper procedures to do my job right. We use problem solving techniques to get the real cause of problems. I am able to meet the requirements of my external customers. A partnership with suppliers supports the ability to improve processes. My supervisor is concerned more about the quality of my work than

the quantity of my work.

Quality is seen to reduce cost and improve productivity.

TQM is seen essential for customer satisfaction and profitability therefore

management includes customer satisfaction scores as a key plan measure.

Management demonstrates leadership, commitment and involvement. Our commitment to quality is what sets us apart from our competitors.

aStarted with the highest mean score.bStarted with the lowest mean score.

but improved systems and working practices which are more related to the hard element of culture was ranked fifth.

In addition, despite the educational reform in Qatar for greater accountability, improved accountability requirement was not perceived as a major benefit or improvement gained from implementing TQM–quality initiatives by the total re-spondents (M=3.26) except for the respondents from pri-mary institutions (M = 4). This observation raised a new question: “Will further systemization and being account-able to external accreditation bodies makes jobs more de-manding?” As such, this helps to explain why improved employee–customer satisfaction was not perceived as an ex-tensive affect of TQM–quality initiatives by total respondents (M=3.32) except for respondents from primary institutions (M=4.2). Thus, this finding confirmed previous arguments that TQ culture transformation and its full benefits will be difficult without the cumulative influence of all the leverage points being used simultaneously. Secondly, it confirmed Psychogios and Priporas’s (2007) argument that managers tend to see TQM from its hard aspects and the actual aware-ness of its soft side is often superficial and people have a relatively poor understanding of it.

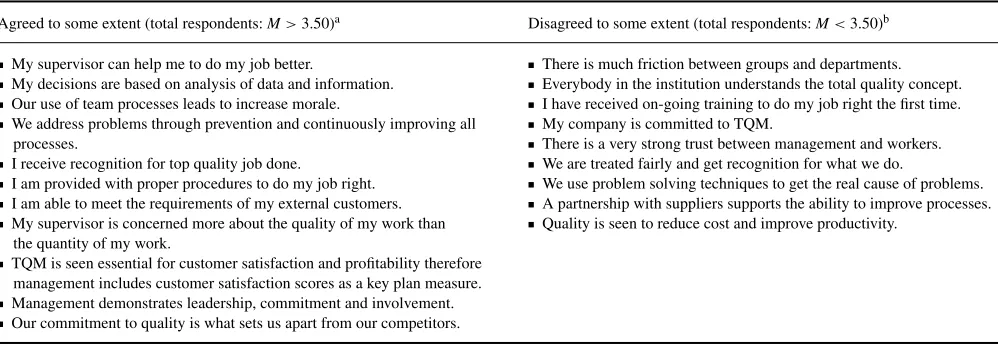

Analysis of TQM Environment for TQ Culture

The questionnaire were based on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) per-taining to perception question asked (see Table 7).

Table 6 shows total respondents’ perception on 20 state-ments that relate to the 1 CSFs influencing the environment for TQ culture. However, the interdependence of these fac-tors makes it difficult to categorize the measurement vari-ables descriptions/statements to fit in with only one CSF. The ANOVA analysis on the 20 statements indicated that there were no statistically significant differences of views (as

shown in thep column) between the three different levels of institutions, except for “Our use of team processes lead to increase morale.” This shows that there is almost a consensus among the three levels of institutions on the level of quality management in their organization.

When the total respondents’ views on the twenty state-ments were classified into “agreed to some extent” and “dis-agreed to some extent” (Table 7), the results shows that 11 statements indicated mean scores greater than or equal than 3.50 (i.e., agreed to some extent) and nine statements indi-cated mean scores less than or equal to 3.50 (i.e., disagreed to some extent). The mean scores ranged from 2.71 and 3.76. These indicated that their agreement or disagreement on the 20 statements was only moderate.

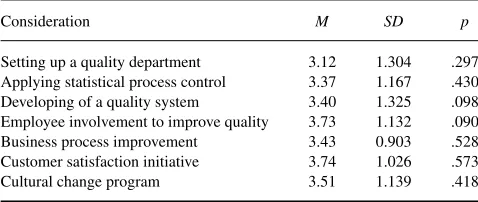

Analysis of the Most Important Issues Related to TQM Initiative Efforts

Table 8 shows the results of perceptions on the most impor-tant issues related to TQM initiative efforts. When respon-dents were asked, “How important are the following issues in your organization’s TQM initiative efforts?” Customer satisfaction initiative (M =3.74), employee involvement to improve quality (M =3.73), and cultural change program (M =3.51) were ranked as the first three most important issues related to TQM initiative efforts respectively by the total respondents. In addition, the ANOVA analysis shows a consensus of views among the three levels of institutions on these issues.

As has been said previously, findings from this section have shown another promising development in terms of how educational institutions in Qatar prepare themselves for TQ culture transformation. Oakland (1997) defined culture in any business as the beliefs which pervade the organization about how business should be conducted, and how employees

TABLE 8

The Most Important Issues Related to TQM Initiative Efforts

Consideration M SD p

Setting up a quality department 3.12 1.304 .297 Applying statistical process control 3.37 1.167 .430 Developing of a quality system 3.40 1.325 .098 Employee involvement to improve quality 3.73 1.132 .090 Business process improvement 3.43 0.903 .528 Customer satisfaction initiative 3.74 1.026 .573 Cultural change program 3.51 1.139 .418

should be treated, or culture emerges in an organization be-cause of the need for solutions to business problems. Bebe-cause the central focus of TQM initiative efforts were more toward soft cultural issues (e.g., employee involvement) rather than hard cultural issues (e.g., quality system), the results support the view that they are moving in the right direction in terms of TQM strategy for TQ culture transformation.

DISCUSSION

Limitations

As with many exploratory studies, this research has some limitations that should be expanded on in future research. The principal limitation of the study is that the sampling pro-cedure covered primary, secondary, and tertiary institutions whereas future studies might focus on a single academic clas-sification. In addition, there were no attempts to increase the number of usable surveys. Also, the results would have been more beneficial if the research questions had aimed to pro-vide an in-depth analysis of the differences in TQM among private versus semigovernment institutions.

Finally, the findings would have been enriched if addi-tional research methods were applied such as semi-structured individual interviews or focus groups. Nevertheless, this re-search can serve as the first step in closing the gap in the dearth of research on TQM implementation in educational institutions in Qatar.

Conclusions

This study reveals many aspects of the extent and nature of TQM within academic institutions in Qatar. Of the 51 respondents from 37 institutions participating in the survey, only 28% of respondents implemented or planned TQM in the workplace. However, nearly half or 49% of respondents knew the purpose of TQM in general and more than three fifths or 64.7% perceived their supervisor or coordinator as an active support of TQM in the workplace. A number of key insights have been identified from this research, which were the following:

• Most educators in Qatar would rather modify than sat-isfy the needs of their customer (students). Table 4 shows providing service the customer wants was not defined as critical to quality job as compared with high standard of service.

• Managerial roles can be the starting point for leaders intent on transforming the culture but cultural transfor-mation may not happen without top down total involve-ment. Table 4 shows 69.4% agreeing on the item “ev-eryone should be responsible or has a role on achieving TQM,” whereas Table 4 shows (64.7%) perceived their supervisor–coordinator as an active support of TQM at workplace.

• Lack of team-based approach due to the traditional au-tonomous role and significant degree of internal compe-tition of academics can be reduced when academic insti-tutions implemented and planned TQM in the workplace. Table 6 shows that teamwork was the most important benefit or improvement from implementing TQM–quality initiatives in the workplace.

• Those institutions who planned or implemented TQM did not perceive any strong positive affect of TQM–quality initiatives as they may be still at the early stage of TQM implementation. Table 4 shows only 49% of total respon-dents knew the purpose of TQM.

• Despite the educational reform in Qatar for greater ac-countability, improved accountability requirement was not perceived as a major benefit or improvement gained from implementing TQM–quality initiatives as it may make jobs more demanding due to lack of education and train-ing; and a lack of employee commitment and motivation due to lack of involvement and effective communication. This study shows that of the 11 CSFs, education, training, and development, followed by communication for TQM, had the lowest total respondent mean score. In addition, it shows that employee involvement to improve quality is considered as the second most important issues related to TQM initiative efforts.

• Cultural changes are unlikely to occur simply by a quick fix approach to improving employee awareness and when all the leverage points mentioned in Figure 1 are not being used simultaneously. Consequently, suspicion and resis-tance are the most common reaction to new paradigm and TQM is less easy to be achieved, especially when many elements of academic culture or when the TQM environment is not receptive to TQM. Table 5 shows that total respondents from institutions that have imple-mented/planned TQM do not believe that their institution gained any extensive benefits/improvement in organiza-tional change (M=3.37) and greater employee commit-ment and motivation (M=3.16) were ranked as the least benefits or improvement gained. In addition, all the 1 CSFs in Table 6 rated by the total respondents were having (Ms

<4).

• Teamwork (M =3.95), increased quality of service and performance (M = 3.68), and increased competitive-ness (M = 3.63) were ranked as the three most impor-tant benefits or improvement gained from implementing TQM–quality initiatives as shown in Table 6. Thus, those mentioned factors can be considered as the strongest driv-ing forces for TQM in Qatari educational institutions.

Finally, the previous evidence has showed that the dom-inant perception of TQM, in general, is positive where a service quality perspective is beginning to be accepted in Qatari educational institutions. Second, the culture of ed-ucational institutions in Qatar is moving toward collective consciousness and teamwork rather than the traditional au-tonomous role or hierarchical culture that was found a decade ago.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the respondents who participated in the questionnaire survey and all agencies that assisted them in offering requested information and data.

REFERENCES

Al-Attiyah, A., & Khalifa, B. (2009). Small steps lead to quality assurance and enhancement in Qatar University.Quality in Higher Education,15, 29–38.

Al-Azmeh, Z. (2006). Redefining the corporate identity of Qatar University. Tawasol Qatar University Reform Newsletter, Spring, 4–5.

Al-Khalifa, K. N., & Aspinwall, E. M. (2000). The development of total quality management in Qatar.The TQM Magazine,12, 194–204. Al-Khalifa, K. N., & Aspinwall, E. M. (2001). Using the competing values

framework to investigate the culture of Qatar industries.Total Quality Management Journal,12, 417–428.

Atkinson, P. E. (1990).Creating cultural change: The key to successful total quality management. Bedford, MA: IFS.

Berry, T. H. (1991).Managing the total quality transformation. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Biehl, R. E. (1999).Customer-supplier analysis in educational change. (Un-published master’s thesis.) Walden University Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

Bolton, A. (1995). A rose by any other name: TQM in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education,3(2), 13–18.

Bounds, G., Yorks, L., Adams, M., & Ranney, G. (1994). Beyond total quality management: Toward the emerging paradigm. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Brookes, M., & Becket, N. (2007). Quality management in higher education: A review of international issues and practice.International Journal for Quality and Standards,1(1), 85–121.

Davies, J., Douglas, A., & Douglas, J. (2007). The effect of academic culture on the implementation of the EFQM Excellence Model in UK universities. Quality Assurance in Education,15, 382–401.

Eagle, L., & Brennan, R. (2007). Are students customers? TQM and mar-keting perspectives.Quality Assurance in Education,15, 44–60. Evans, J. R. (2007). Quality and performance excellence: Management,

organization, and strategy(5th ed.). Columbus, OH: Thomson South-Western.

Evans, J. R., & Lindsay, W. M. (2008).The management and control of quality(7th ed.). Columbus, OH: Thomson South-Western.

Fryer, K. J., Antony. J., & Douglas, A. (2007). Critical success factors of continuous improvement in the public sector.The TQM Magazine,19, 497–517.

Ghobadian, A., & Speller, S. (1994). Gurus of quality: A framework for comparison.Total Quality Management,5(3), 53–69.

Hides, M. T., Davis, J., & Jackson, S. (2004). Implementation of EFQM excellence model self-assessment in the UK higher education sector: Lessons learned from other sectors.The TQM Magazine,16, 194–201. Hill, T., & Lewicki, P. (2006).Statistics. Method and applications. A

com-prehensive reference for science, industry and data mining(1st ed.). Tulsa, OK: Wyd.

Hwarng, H. B., & Teo, C. (2001). Translating customers’ voices into opera-tions requirements: A QFD application in higher education.International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management,18, 195–226.

Juran, J. M., &. Gryna, F. M. (1982).Quality planning and analysis. New Delhi, India: Tata McGraw-Hill.

Kanji, G. K. (n.d.). Performance excellence: Path to integrated management. Retrieved from http://worldcat.org/title/performance-excellence-path-to-integrated-management-and-sustainable-sucess/oclc/ 807871609&referer=brief results

Kanji, G. K., Tambi, A. M., & Wallace, W. (1999). A comparative study of quality practices in higher education institutions in US and Malaysia. Total Quality Management,10, 357–371.

Kanji, G. K., & Yui, H. (1997). Total quality culture.Total Quality Manage-ment,8, 417–428.

Koch, J. V. (2003). TQM: Why is its impact in higher education so small? The TQM Magazine,15, 325–333.

Koslowski, F. A. (2006). Quality and assessment in context: A brief re-view, quality assurance in education.Quality Assurance in Education, 14, 277–288.

Lascelles, D. M., & Dale, B. G. (1993).The road to quality. Oxford, England: IFS.

Mann, R., & Kehoe, D. (1995). Factors affecting the implementation and success of TQM.International Journal of Quality and Reliability Man-agement,12, 11–23.

McCormick, B. L. (1993).Quality and education: Critical linkages. Prince-ton Junction, NJ: Eye On Education.

Nunnaly, J. (1978).Psychometric theory. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Oakland, J. S. (1997). Interdependence and cooperation: The essentials of

TQM.Total Quality Management,8, 31–55.

Pallant, J. (2001).SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS for Windows(Version 10). St Leonards, Australia: Allen and Unwin.

Porter, L. P., & Parker, A. J. (1993). Total quality management: The critical success factors.Total Quality Management,4, 13–22.

Psychogios, A. G., & Priporas, C. V. (2007). Understanding total quality management in context: Qualitative research on managers’ awareness of TQM aspects in the Greek service industry.The Qualitative Report,12, 40–66.

Qatar Statistics Authority. (2009).Labour force sample survey 2008. Re-trieved from http://www.qsa.gov.qa/eng/News/2009/Articles/23.htm Qatarization. (2009). Mission statement. Retrieved from http://www.

qatarization.com.qa/qatarization/qat web.nsf/

Quazi, H. A., & Padibjo, S. R. (1998). A journey toward total quality man-agement through ISO 9000 certification: A study on small and medium sized enterprises in Singapore.International Journal of Quality and Re-liability Management,15, 489–508.

Sahney, S., Banwet, D. K., & Karunes, S. (2004a). A SERVQUAL and QFD approach to total quality education: A student perspective. In-ternational Journal of Productivity and Performance Management,53, 143–166.

Sahney, S., Banwet, D. K., & Karunes, S. (2004b). Conceptualizing to-tal quality management in higher education.The TQM Magazine,16, 145–159.

Salaheldin, I. (2009). Problems, success factors and benefits of QCs implementation: A case of QASCO. The TQM Journal, 21, 87–100.

Salaheldin, I., & Zain, M. (2007). How quality control circles enhance work safety: A case study.The TQM Magazine,19, 229–44.

Singh, V., Grover, S., & Kumar, A. (2008). Evaluation of quality in an edu-cational institute: A quality function deployment approach.Educational Research and Review,3, 162–168.

Sirvanci, M. B. (2004). TQM implementation: Critical issues for TQM implementation in higher education. The TQM Magazine, 16, 382–386.

Srikanthan, G., & Dalrymple, J. F. (2002). Developing a holistic model for quality in education. Quality in Higher Education, 8, 215–224.

Srikanthan, G., & Dalrymple, J. F. (2004). A synthesis of a quality man-agement model for education in universities.International Journal of Educational Management,18, 266–279.

Sulaiman, N. F. (2002). The development of a dual phase approach to embracing a total quality culture in the Malaysian construction indus-try. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation.) Glasgow Caledonian University, Scotland.

Supreme Education Council of Qatar. (2009).Education for a new era. Retrieved from http://www.sec.gov.qa

Wilkinson, A., Redman, T., & Snape, E. D. (1994). The problems with quality management: The view of managers: Findings from an Institute of Management survey.Total Quality Management and Business Excellence, 5, 397–406.

World Bank. (2007). Turning Qatar into a competitive knowledge-based economy: Opportunities and challenges. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/KFDLP/Resources/QatarKnowledge EconomyAssessment.pdf

Yeo, R. K. (2008). Brewing service quality in higher education: Charac-teristics of ingredients that make up the recipe.Quality Assurance in Education,16, 266–286.