INDONESIAN FISHERIES RESEARCH JOURNAL

Manuscript send to the publisher:

Indonesian Fisheries Research Journal

Research Center for Capture Fisheries

Jl. Pasir Putih I Ancol Timur Jakarta 14430 Indonesia

Phone (021) 64711940

Fax: (021) 6402640

Email:drprpt2009@gmail.com

Indonesian Fisheries Research Journal is published by Research Center for Capture

Fisheries. Budgeting F.Y. 2009.

ISSN 0853 - 8980

Published by:

Agency for Marine and Fisheries Research

Volume 15 Number 1 Juni 2009

Acreditation Number: 101/Akred-LIPI/P2MBI/10/2007

(Period: November 2007-November 2010)

Indonesian Fisheries Research Journal is the English version of fisheries research journal.

The first edition was published in 1994 with once a year in 1994. Since 2005, this journal

has been published twice a year on JUNE and DECEMBER.

Head of Editor Board:

Prof. Dr. Ir. Endi Setiadi Kartamihardja, M.Sc.

Members of Editor Board:

Prof. Dr. Ir. John Haluan, M.Sc. Prof. Dr. Ir. Subhat Nurhakim, M.S.Dr. Ir. Wudianto, M.Sc. Prof. Dr. Ir. Indra Jaya, M.Sc.

Refrees for this Number:

Prof. Dr. Ir. Ari Purbayanto, M.Sc. (Bogor Agricultural Institute) Prof. Dr. Ir. Setyo Budi Susilo, M.Sc. (Bogor Agricultural Institute)

Dr. Ir. Augy Syahailatua (Research Center for Oceanography- The Indonesian Institute of Sciences)

Managing Editors:

Ir. Chairulwan Umar, M.Si.i

PREFACE

Indonesian Fisheries Research Journal Volume 15 Number 1 June 2009 is the first publication of Research Center for Capture Fisheries in 2009. The second number of journal will be published in December 2009. This journal is expected to expand communication among fisheries scientiest entirely part of the country as well as other scientific in the tropical countries. This journal is financially supported by the Research Center for Capture Fisheries, budgeting F.Y. 2009.

This volume contains one article discussing of heavy metal (Ni, Cr) at the bottom layer of Matano Lake, South Sulawesi and the rest five figuring out marine fisheries resources relating to taxonomy of eightbar grouper, biodiversity of sharks and rays, biological reproductive of estuarine fishes as well as the blue spotted maskray, and Arafura Fisheries management of red snapper.

We would like to thank to the referees for their effort and contribution in reviewing and correcting the manucripts.

ISSN 0853 - 8980

INDONESIAN FISHERIES RESEARCH JOURNAL

Vol. 15 No. 1 - Juny 2009

CONTENTS

Page

i

iii

1-7

9-16

17-28

29-35

37-42

43-48

PREFACE ………... CONTENTS ……….. Concentration of Nickel (Ni) and Chromium (Cr) in Sediment and Suso Snail (Tylomelania patriarchalis) at Bottom Layer of Matano Lake, South Sulawesi

By: Kamaluddin Kasim and Mas Tri Djoko Sunarno ……….. Changes to the Red Snapper Fisheries in the Arafura Sea Fisheries Management Area

By: Siti Nuraini and Tri Ernawati ... Biodiversity of Sharks and Rays in South-Eastern Indonesia

By: Dharmadi, Fahmi, and William White ………. Size at First Maturity of the Blue Spotted Maskray, Neotrygon kuhli in Indonesian Waters

By: Fahmi, Mohammad Adrim, and Dharmadi ………...………. Biological Reproductive of Estuarine Fish Comparing Between Demersal (Long Tongue Sole, Cynoglossus lingua) and Pelagical (Mustached Thryssa, Thryssa mystax) Assemblages

By: M. Muklis Kamal and Mas Tri Djoko Sunarno ……….. First Record of Eightbar Grouper, Epinephelus octofasciatus Griffin, 1926 (Perciformes: Serranidae) from Indonesia

17

Biodiversity of Sharks and Rays in South-Eastern Indonesia (Dharmadi et al.)

BIODIVERSITY OF SHARKS AND RAYS IN SOUTH-EASTERN INDONESIA

Dharmadi1), Fahmi2), and William White3) 1) Research Centre for Capture Fisheries, Ancol-Jakarta

2) Research Centre for Oceanography-Indonesian Institute of Sciences, Ancol-Jakarta 3) Ichthyologist, CSIRO Marine & Atmospheric Research, Hobart, Australia

Received May 4-2009; Received in revised form May 18-2009; Accepted May 22-2009

ABSTRACT

Indonesia has a very diverse shark and ray fauna and is the largest chondrichthyan fisheries in the world. Most of the sharks are caught by longlines and gillnets and rays are caught both as target, e.g. in the tangle net and demersal gillnet fisheries, and as bycatch in other fisheries such as in demersal and drift gillnet, trammel net and long line fisheries. The sharks and rays caught from the Indian Ocean, adjacent to Indonesia, were mostly landed at artisanal fisheries in south-eastern Indonesia, such as Pelabuhan Ratu (West Java), Cilacap (Central Java), Kedonganan (Bali), Tanjung Luar (East Lombok), and Kupang (West Timor), and Merauke (West Papua). Surveys were conducted at these fish landing sites between April 2001 and March 2006, with a total of 80 species of sharks belonging to 21 families recorded. The dominant shark family was the Carcharhinidae with 27 species. A high diversity of sharks was recorded at Kedonganan (49 species), at Tanjung Luar (47 species), at Cilacap (32 species), and at Pelabuhan Ratu (27 species). A total of 55 species of rays belonging to one of 12 families were recorded from the same landing sites. The most speciose and commonly recorded family of rays was the Dasyatidae, which was represented by 28 species, and contributed 65.2% to the total number of chondrichthyan individuals recorded. The most abundant dasyatids recorded were the smaller ray species Neotrygonkuhlii, Dasyatis zugei, and Himantura walga, and the larger species Himantura gerrardi and Himantura fai which collectively comprised 57.8% of the total number of all chondrichthyans landed.

KEYWORDS: shark, ray, biodiversity, south-eastern Indonesia

INTRODUCTION

Indonesia is known as having the highest diversity of elasmobranches (sharks and rays) in the world (Blaber, 2006), with their fishery production reported as 100,037 tones in 2005 (Directorate General of Capture Fisheries, 2007) and then increased to be 110,528 tones in 2006 (Directorate General of Capture Fisheries, 2008). Most elasmobranches are caught opportunistically through-out Indonesian waters, mainly in coastal artisanal fisheries and bycatch of commercial shrimp trawlers (Keong in Camhi et al.,

2008). The reported elasmobranch landings in Indonesia consist of 66% sharks and 34% rays, of which, members of the Dasyatidae are, by far, the most dominant species (Carpenter & Niem, 1999; Stevens et al., 2000). In 2006, a study conducted by fisheries scientist, Shelley Clarke, indicated that up to 73 million sharks are now being killed annually to supply the fin trade. This was three times higher than the official catch statistics reported by the FAO, because it included new data taken from illegal shark fin traders who unreported their catches

(www.elasmodiver.com/Shark books).

The diversity of sharks was recorded of about 375-500 species in the world, which was dominated by the order of Carcharhiniformes (ground sharks; 56%).

There are three other major groups, Squaliformes (dogfish sharks), Orectolobiformes (carpet sharks), and Lamniformes (mackerel sharks) that respectively comprise 23, 8, and 4% of the living sharks (Demski & Wourms, 1993; FAO, 2000). More than 400 species of chondrichthyes consist of sharks, rays, and chimaera (600 species) in the world (Camhi et al., 1998); Compagno (1984; 2002). While Fahmi & Dharmadi (2005) estimated that Indonesian waters contain more than 200 chondrichthyan species.

The high diversity of the elasmobranch fauna in Indonesia has been well documented by Gloerfelt-Tarp & Kailola (1984), Last & Stevens (1994), Carpenter & Niem (1999). Elasmobranchs are caught in Indonesia by both as target fisheries and as bycatch in other fisheries. Target fisheries, which are mainly artisanal, use a variety of fishing methods, such as gillnets, trammel nets, purse seines, longlines, and droplines. The fisheries that land substantial catches of elasmobranchs as a bycatch include the prawn and fish fishery exploited by commercial trawlers and pelagic tuna fisheries. Although Indonesia has the largest chondricthyan fishery and is considered to have one of the richest chondrichthyan fauna in the world, there are almost no published biodiversity of sharks and rays in Indonesia. In a region where shark and ray population are amongst the most heavily

Corresponding author:

exploited, taxonomic knowledge of Indonesia’s chondricthyan fauna needs to improve in order to provide an adequate baseline for data acquisition and resource management (White et al., 2006).

This paper describes on species identification and species composition of sharks and rays and their fishery at fish landing sites in south-eastern Indonesia. MATERIALS AND METHODS

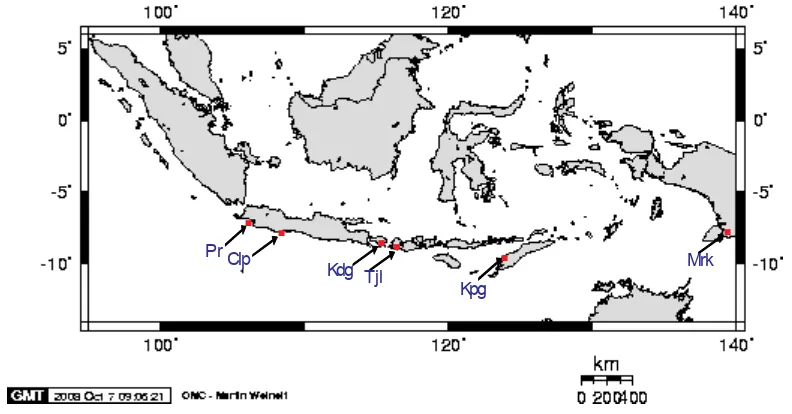

A Study on elasmobranch species was conducted from April 2001-March 2006 at several landing sites and fish a long the coast of Indian Ocean, particularly from Pelabuhan Ratu (West Java), Cilacap (Central Java), Kedonganan (Bali), Tanjung Luar (East Lombok), Kupang (West Timor), and Merauke (West Papua). Those sites were visited regularly during the study. Twenty one trips were done at Kedonganan and Tanjung Luar, and fifteen trips were done at Cilacap and Pelabuhan Ratu, while one trip was done in Kupang and Merauke. Each trip was conducted within 2-7 days. Shark and ray species was identified using descriptions in Compagno et al. (1984); Last & Stevens (1994); Campagno (1998; 1999); Gloerfelt-Tarp & Kailola (1984). The location and a description of the landing sites surveyed in south-eastern Indonesia are given in Figure 1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

Diversity of Sharks and Rays

All species of sharks and rays found during this study are listed in Appendix 1. A total of 19,634

chondrichthyan fishes, representing 135 species and 29 families, were recorded collectively at the landing sites in south-eastern Indonesia between April 2001 and March 2006. This total specimen comprised of 80 species of shark representing 21 families and 55 species of ray representing 12 families. A high diversity of sharks was found at Kedonganan-Bali (49 species), at Tanjung Luar (47 species), at Cilacap (32 species), at Pelabuhan Ratu (27 species), and low diversity of sharks was found at Kupang and Merauke i.e. 5 and 4 species, respectively. While diversity of rays was found at each landing sites i.e. Kedonganan (32 species), Tanjung Luar (14 species), Cilacap (13 species), Pelabuhan Ratu (9 species), Merauke (5 species), and Kupang (2 species) (Figure 2).

The dominant sharks family was the Carcharhinidae with 27 species and they were recorded from this fishery in south-eastern Indonesia. However, the most common shark species found from this family were Carcharhinus falciformis and

Carcharhinus brevipinna, which together comprised 27.1% of the total number of sharks caught (Appendix 1). Whereas the most specious and commonly recorded family of rays was Dasyatidae, represented by 23 species, and contributed 87.3% to the total number of ray individuals recorded. The most abundant Dasyatids recorded were the smaller ray species i.e.

Neotrygon kuhlii, Dasyatis zugei, and Himantura walga, and the larger species was Himantura gerrardi

which collectively comprised 84.2% of the total number of all rays landed. Most of sharks were caught by longlines where some species of sharks i.e. Alopias pelagicus, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, Carcharhinus

Figure 1. Map of the study area and observed landing sites in south-eastern Indonesia.

Ind.Fish Res.J. Vol.15 No.1 Juny-2009: 17-28

Remarks: Fish landing sites of Pr: Pelabuhan Ratu, Clp: Cilacap, Kdg: Kedonganan, Tjl: Tanjung Luar, Kpg: Kupang, Mrk: Merauke

. .

. .

.

.

PrClpKdg Tjl

Kpg

19 Figure 2. Numbers of species of sharks and rays recorded at each landing site.

falciformis, Prionace glauca, and Sphyrna lewini

contributed 62% to the pelagic fisheries. Another abundant species from the tuna gillnet fisheries i.e.

C. sorrah, Rhizoprionodon oligolinx, and Scoliodon laticulatus which together comprised contributed 55% to the pelagic fisheries, and only one species was caught i.e. Prionace glauca from the tuna longline fisheries and contributed 27% (Figure 3a). While the most abundant species of Squalus hemippinis

contributed 42% to the demersal longline fisheries (Figure 3b).

The extents to which sharks and rays move within and between different habitats vary greatly. For example, the blue shark Prionace glauca is capable of trans-oceanic migrations in excess of 16,000 km, whereas some species of horn sharks have been observed foraging in the same area of reef each day and returning to shelter in the same cave every night (Tricas et al., 1997). Some species, such as the grey reef shark, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, from small to large aggregations over reefs (Last & Stevens, 1994; Tricas et al., 1997). Most Carcharhinidae i.e. silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) and spinner shark (Carcharhinus brevipinna) are highly migratory species and they are solitary and often over schools of tuna. Those species inhabit the continental and insular shelves and slopes, deepwater reefs, and open seas. They are also occasionally sighted in inshore waters (Marinebio.org/species.asp.). Most species of rays recorded were living in coastal and continental shelf and the some species which were found in the oceanic mainly the family of Mobulidae.

Based on morfometric methode, we estimated that probably at least there were 27 new species had been found in the south-eastern Indonesia during this study. However ten species have been published, such as some of them are Hemitriakish indroyonoi (White et

al. 2009), Mustelus widodoi (White & Last, 2006),

Rhinobatos jimbaranensis and Rhinobatos penggali

(Last et al., 2006) and 17 species are currently known. From all species of sharks and rays had been identified during this study we estimated that at least there were 16 species of them possibly endemic species in Indonesia waters, for instance species of Hemitriakish indroyonoi, Himantura walga, and Dasyatis parvonigra

were found in south of Java Sea, Rhinobatos jimbaranensis, Rhinobatos penggali, Atelomycterus baliensis, and Mustelus widodoi were found in continental shelve close to the Bali and Lombok Island, and others endemic species had been found in continental shelve near Merauke-West Papua are

Dasyatis sp.1 and Himantura hotlei.

Species Composition of Sharks and Rays

Species compositions of sharks were shown in Appendix 1. From the number of 6,107 individuals of sharks recorded, Carcharhinus falciformis and

Carcharhinus brevipinna from the family of Carcharhinidae and Squalus spp. of the family of Squalidae were dominated, with the percentages of 14.9, 12.2, and 22.1% from the total individuals recorded, respectively. Whiles from 13,527 individuals of rays recorded, the family of Dasyatidae which was represented by Neotrygon kuhlii, D. zugei, Himantura gerrardi, H. walga, was dominated with percentages of 42, 17.9, 13.2, and 9.8% from the total individuals recorded, respectively.

The greatest number of species of sharks and rays recorded were at Kedonganan and Tanjung Luar, i.e.

81 and 60, respectively, and the least were at Kupang and Merauke, i.e. 7 and 9, respectively. The family of Carcharhinidae and Dasyatidae in this study made the greatest contribution to the total estimated biomass of chondrichthyans, i.e. 36.6 and 60.2%,

respectively, which Himantura fai, Pastinachus sephen, Neotrygon kuhlii, Prionace glauca, Carcharhinus falciformis, and Carcharhinus brevipinna

were the greatest contributors. Shark and Ray Fishery

Pelagic longline fisheries targeting large carcharhinid sharks were observed operating out of the landing sites of Palabuhan Ratu and Tanjung Luar. The longlines, which range in length from 3,000-5,000 m, each contains between 400 and 600 hooks. The longliners from Pelabuhan Ratu operate in oceanic waters off West Sumatera as well as southwards towards Australian waters. At Tanjung Luar, the longliners operate in both oceanic and inshore waters off south Flores, Sumbawa, and further south to Sumba. At both sites, the number of boats at this fishery are relatively large, e.g. >50 at Tanjung Luar, and the boats remain at sea for 7-15 days. All sharks landed in this fishery at these two sites are typically

landed whole, i.e. not finned and-or trunked at sea. The fins are taken away for drying and supplied to the oriental shark-fin traders which pay in high prices while the flesh is also used as either fresh, smoked or salted, and dried meats for human consumption. A total of 21 species of shark was recorded from this fishing gear type at these two sites. The most abundant species caught in pelagic longlines fishery were Alopias pelagicus, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, Carcharhinus falciformis, Prionace glauca, and Sphyrna lewini (Figure 3a).

Demersal longline fisheries that target mainly squaloids were observed operating out of the landing sites of Pelabuhan Ratu, Cilacap, Kedonganan, and Tanjung Luar. The main fishery that operates out of Cilacap is pelagic gillnetting and longlining for tuna which they involve a high bycatch of pelagic sharks. Other smaller fisheries also exist, including one for prawns, demersal trammel-netting for small teleosts, with a small bycatch of batoids, and deep-water

Ind.Fish Res.J. Vol.15 No.1 Juny-2009: 17-28

21 demersal longlining for squaloids. The longlines used

by these fisheries vary between landing sites, with only small longlines, i.e. ca 200 m in length, being used at Kedonganan and larger lines, i.e.>2,000 m in length, being employed at Pelabuhan Ratu and Tanjung Luar. The catches from this fishery at most sites appear to be highly seasonal. The livers of the squaloid sharks were excised immediately upon landing and the squalene oil, which has a high export value, subsequently extracted. The livers of the large deep-water centrophorids, namely Centrophorus niaukang and Centrophorus squamosus, were the most sought after as they possess extremely large livers with high squalene levels. The fins and vertebrae were dried for either export or local use and the flesh is salted and dried for human consumption.

A demersal gillnets fishery targeting a small ray was observed operating out of the landing site of Kedonganan in Bali. The gillnets, which are ca 1,200 m in length with 100 mm mesh, are deployed from a number of small boats (<10 m in length) that operate in relatively shallow water, i.e.<30 m, in the Jimbaran Bay. These boats only remain at sea for one or two nights and typically land less than a hundred small-medium rays on each occasion. Fleshes of all of the rays landed were utilized locally for human consumption.

The landing site of Kupang (West Timor) was also visited on one occasion by the two Indonesian project scientists, but, due to the limited chondrichthyan catches, i.e. only seven species, this site was not surveyed on subsequent trips. The main fishery operating from the fishing port in Merauke was trawling. However, since the catches were unloaded at sea into a larger ship for direct export, the catches cannot be observed. Elasmobranchs are also targeted by demersal gillnet fishers operating in the Arafura Sea, but these were also unloaded at sea. On the other hand, along the Merauke coastal communities, fishers used set gillnets from either the shore or slightly offshore from the coast to target teleosts but also catch a small number of sharks. Seine net fishermen operating from the shore target penaeid prawns but also catch a small number of rays. DISCUSSION

The total of 131 species of sharks and rays recorded during the present study was reflecting, in part, the limited amount of deepwater fisheries (i.e.

>200 m in depth) in this region. Those deeper waters contain a number of species, including certain

Centrophorids, Etmopterids, Somniosids, Squalids, Scyliorhinids, and Rajiids, which were not recorded

during the present study. The importance of deep waters in terms of chondrichthyan diversity is emphasized by the fact that, although deepwater demersal longlining (60-600 m in depth) was probably the least extensive of the fisheries, the number of chondrichthyans caught by this fishery, i.e.35, was the greatest of all of the chondrichthyan fisheries examined in Indonesia. The large number of chondrichthyan species recorded at the landing sites in south-eastern Indonesia during this study reflects the high diversity of this group of fishes in this region (Last & Stevens, 1994; Carpenter & Niem, 1999).

A total of 79 species of sharks belonging to 21 families and 52 species of rays belonging to 12 families recorded in this study. A high diversity of sharks and rays was found at Kedonganan-Bali (81 species), Tanjung Luar (60 species), Cilacap (46 species), Pelabuhan Ratu (36 species), Kupang (7 species), and Merauke (9 species). The differences of shark and ray diversity at those landing sites were due to the species compositions of the catches at those landing sites were influenced by a very large degree of type of fishing gears used by the fishers supplying those landing sites and the types of environment in where fishes were caught. In terms of the number of species and numbers of individuals, the catches were dominated by species belonging to the Carcharhinidae and Dasyatidae. This reflects that these two families are the most speciose and abundant elasmobranchs in the inshore waters of tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world (Compagno, 1984; Carpenter & Niem, 1999). Manjaji (1997) mentioned that the biodiversity of elasmobranchs in Malaysian waters was dominated by family of Dasyatidae (24 species), following by Myliobatidae (5 species) and Mobulidae (4 species). Whiles in the Thailand waters, 23 spesies of family Dasyatidae were recorded in the area (Vidthayanon, 1997).

The Carcharhinidae (whaler or requiem sharks) is one of the largest families of sharks and the most important of those families in terms of artisanal and commercial fisheries in tropical regions (Compagno, 1984; Bonfil, 1994). One of the species of the family Carcharhinidae i.e. Carcharhinus falciformis is considerably important to the longlines and gillnets fisheries in many parts of the world. In the Gulf of Mexico, it is often caught as bycatch in the tuna fishery but also harvested by the directed shark fishery (Marinebio.org/species.asp.). In Indonesian waters,

Carcharhinus falciformis is not a target species in the shark fishery but it is often caught by shark surface longline and as bycatch in the tuna fishery, this indicated that Carcharhinus falciformis was biggest

percentage contributed of the total number of shark individual recorded. Whereas, in Japanese waters,

Carcharhinus falciformis is the most common target species of the shark fishery and also caught as bycatch by the swordfish and tuna fisheries. (Marinebio.org/species.asp.). Furthermore, Oshitani

et al. (2003) mentioned that, the catch of silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) was the most common shark taken by purse seine fisheries in eastern Pacific Ocean and it contributed for 25% of all sharks caught. Family of Dasyatidae was found in a large number at the continental shelve in both tropic and sub tropic in the world, where its members make a very important contributions to both the artisanal and commercial fisheries (Compagno, 1984; Carpenter & Niem, 1999). This family is represented by more than 60 living species that belongs to five genera, i.e. Dasyatis, Himantura, Pastinachus, Taeniura, and Urogymnus,

with the majority residing in the first two of these genera (Last & Stevens, 1994). The small sizes of some commercial rays were dominated in the catches of rays in Asian countries (Carpenter & Niem, 1999), for example Dasyatis kuhlii. This species, which is very common in inshore waters in depths of up to about 90 m, occurs predominantly over sandy substrates (Last & Stevens, 1994). The dwarf whip ray Himantura walga, which is the smallest of the Dasyatid species, with a maximum disc width of only 180 mm, has a limited distribution in the Indo-West Pacific from Thailand to south-eastern Indonesia (Carpenter & Niem, 1999). The habitat of Himantura walga is poorly defined, but this species is the most common large coastal and in inshore waters.

From all landing sites, sharks were caught by various fishing gears, such as bottom long-lines, surface long-lines, gillnets, trammel nets, bottom trawls, and drop lines. Sharks are also caught locally by both target fisheries and as by catch. In general, fisheries that land substantial catches of sharks as bycatch are from bottom trawl, trammel net, gillnet, long-line, and drop line fisheries while the target shark fisheries usually use gillnets, and long-lines, which was particularly carried out in Tanjung Luar in this study. Oceanic pelagic sharks are usually caught longlines but sometimes they are also taken as bycatch by tuna fishers. The main species taken in the tuna longline fisheries is Prionace glauca (27%), while in the tuna gillnets, Rhizoprionodon oligolinx and

Scoliodon laticulatus are dominant which collectively comprised 45%. On the other hand, Carcharhinus falciformis is the most common shark species taken by shark longlines (16%). While the main species taken by demersal longline is Squalus hemippinis

(42%).

CONCLUSION

Family of Carcharhinidae was biggest percentage contribution in the shark’s composition (47.3%) which dominated by Carcharhinus falciformis (14.9%) and

Carcharhinus brevipinna (12.2%). While family of Dasyatidae was biggest percentage contribution in the rays composition i.e. 85.3% which was dominated by Neotrygon kuhlii (42%), Dasyatis zugei (17.9%),

Himantura gerrardi (14.5%), and Himantura walga

(9.8%). The findings of new species in the Indian Ocean indicated that the chondrichthyan diversity in Indonesia has not fully discovered yet. Besides, some species of shark and ray were endemic species in the south Java Sea and in continental shelve close to the Bali, Lombok Island, and Merauke during this study. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The last, we appreciate to Dr. Mas Tri Djoko Sunarno for his contribution in improving sentence of this paper. This paper was presented on world ocean conference in Manado on May 11-15, 2009 collaborated with RCCF in year 2001-2006. The title of the research project was sharks and rays artisanal and their socio-economic in south-eastern Indonesia. We thank to Dr. Stephen Blaber as a project leader from Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization Australia and particularly gratefull to Dr. Subhat Nurhakim (Research Centre for Capture Fisheries) as an Indonesia project leader and special thanks also go to Miss J. Giles (Queensland Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, Brisbane) for her invaluable contribution on the second phase of the research project.

REFERENCES

Blaber, S. J. M. 2006. Artisanal shark and ray fisheries in Eastern Indonesia: Their socioeconomic and fisheries characteristics and relationship with Australian resources. ACIAR PROJECT FIS/2003/ 037 Supplementary Stock Assessment Meeting.

CSIRO Cleveland, Australia. 4 September, 2006. 57pp.

Bonfil, R. 1994. Overview of world elasmobranch fisheries. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper. 341. 119 pp.

Camhi, M., S. Fowler, J. Musich, A. Brantigam, & S. Fordham. 1998. Shark and their relatives, ecology and conservation occasional. Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission. No.20.IUCN. Gland. Switzerland and Cambridge UK. 39 pp.

23 Camhi, M. D., E. K. Pikitch, & E. A. Babcock. 2008.

Sharks of the open ocean biology, fisheries, and conservation. Fish and Aquatic Resources Series 13. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. USA. 337 pp. Carpenter, K. E. & V. H. Niem. (Eds). 1999. FAO

Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes. The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. Vol.3. Batoid Fishes, Chimaeras, and Bony Fishes Part 1 (Elopidae to Linophyrnidae). 1,397-2,068. FAO. Rome. Compagno, L. J. V. 1984. FAO species catalogue.

Vol.4. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of sharks species known to date. Part 1. Hexanchiformes to Lamniformes. FAO Fish. Synop. 125. 4 (1): 249 pp.

Compagno, L. J. V. 1998. Sharks. In K. E. Carpenter, V. H. Niem (Eds) FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes. The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. Vol.2.

Cephalopods, Crustaceans, Holothurians, and Sharks. FAO. Rome. 1.193-1.366.

Compagno, L. J. V. 1999. Batoid Fishes. In K. E. Carpenter, V. H. Niem (Eds) FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes. The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. Vol.3. Batoid Fishes, Chimaeras, and Bony Fishes Part 1 (Elopidae to Linophyrnidae). FAO. Rome. 1.397-1.530.

Compagno, L. J. V. 2002. Shark of the world, an annotated and illustrated catalogue of sharks species known to date. Vol.2. Bulhead, mackerel, and carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes, and Orectobiformes). FAO species catalogue for fishery purpose. Rome. 1 (2): 269 pp.

Demski, L. S. & J. P. Wourms. 1993. The reproduction and development of sharks, skates, rays, and ratfishes introduction, history, overview, and future prospects. In the Reproduction and Development of Sharks, Skates, Rays, and Ratfishes. By J. P. Wourms and L. S. Demski. Kluwer Academic Publishers. London. 299 pp.

Directorate General of Capture Fisheries. 2007.

Capture Fisheries Statistics of Indonesia. Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries. Jakarta. 134 pp. Directorate General of Capture Fisheries. 2008.

Capture Fisheries Statistics of Indonesia. Ministry

of Marine Affairs and Fisheries. Jakarta. 7 (1): 134 pp.

Fahmi & Dharmadi. 2005. Shark fishery status and its management aspects. Oseana. Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia. XXX (1): 1-8. (in bahasa Indonesia).

FAO. 2000. Fisheries management. Conservation and Management of Sharks. Rome. 37 pp.

Gloerfelt-Tarp, T. & P. J. Kailola. 1984. Trawled Fishes of Southern Indonesia and Northwestern Australia.

Australian Development Assistance Bureau. Directorate General of Fisheries. Indonesia. German Agency for Technical Cooperation. 406 pp.

Last, P. R. & J. D. Stevens. 1994. Sharks and Rays of Australia. CSIRO Division of Fisheries. Hobart Australia. 513 pp.

Last, P. R., W. T. White, & Fahmi. 2006. Rhinobatos jimbaranensis and Rhinobatospenggali, two new shovelnose rays (Batoidae: Rhinobatidae) from eastern Indonesia. Cybium. 30 (3): 261-271. Manjaji, B. M. 1997. New Records of Elasmobranch

Species from Sabah. In Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management.

Proceeding of the International Seminar and Workshop. Sabah, Malaysia, July. 70-77. Marinebio.org/species.asp). Small Step Toward Shark

Conservation. July 2009.

Oshitani, S., H. Nakano, & S. Tanaka. 2003. Age and growth of the silky shark Carcharhinus falciformis

from the Pacific Ocean. Fish.Sci. 69: 456-464. Stevens, J. D., R. Bonfil, N. K. Dulvy, & P. A. Walker.

2000. The effects of fishing on sharks, rays, and chimaeras (chondrichthyans), and the implications for marine ecosystems. ICES Journal of Marine Science.57: 476-494.

Tricas, T. C., K. Deacon, P. Last, J. E. McCosker, T.I . Walker, & L. Taylor. 1997. Sharks and Rays.

Readers Digest, NSW.

Vidthayanon, C. 1997. Elasmobranch Diversity and Status in Thailand. In Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management. Proceeding of the International Seminar and Workshop. Sabah, Malaysia, July. 104-113.

White, W. T., P. R. Last, J. D. Stevens, G. K.Yearsley, Fahmi, & Dharmadi. 2006. Economically important sharks and rays of Indonesia. ACIAR Monograph Series. No.124. Perth, WA. 329 pp.

www.elasmodiver.com/Shark books

White, T. W, L. J. V. Compagno, & Dharmadi. 2009.

Hemitriakish indroyonoi sp., a new species of houndshark from Indonesia (Carcharhiniformes: Triakidae). Article, Zootaxa. Magnolia Press. ISSN 1175-5334. 2110:41-57. www.mapress.com/ zootaxa/

White, W. T. & P. R. Last. 2006. Description of two species of smooth-hounds, Mustelus widodoi, and

M. ravidus (Carcharhiniformes: Traikidae from the Western Central Pacific. Cybium. 30 (3): 235-246.

25 Appendix 1. Biodiversity, habitat, and species composition of sharks and rays

0.1 *

Indonesian bird beak dogfish Deania cf. calcea

0.2 *

Dwarf gulper shark Centrophorus atromarginatus

0.5 *

Leaf scale Gulper Shark Centrophorus squamosus

0.8 *

Taiwan Gulper Shark Centrophorus niakung

1.1 *

Small fin Gulper Shark Centrophorus moluccensis

0.1 *

Large fin Gulper Shark Centrophorus cf. lusitanicus

0.4 *

Black fin Gulper Shark Centrophorus isodon

Centrophoridae

0.6 *

Big eye Six gill Shark Hexanchus nakamurai

0.7 *

Blunt nose Six gill Shark Hexanchus griseus

0.5 *

Sharp nose Seven gill Shark Heptranchias perlo

Indonesian spotted catshark Halaelurus maculosus

Indonesian Angel shark Squatina legnota

Squatinidae

0.1 *

* Wing head shark

Eusphyra blochii

Broad fin shark Lamiopsis temmincki

0.1 *

Sickle fin lemon shark Negatron acutidens

0.2 *

Spade nose shark Scoliodon laticaudus

0.4 *

White tip reef shark Triaenodon obesus

0.2 *

Australian sharp nose shark Rhizoprionodon taylori

0.3 *

Grey sharp nose shark Rhizoprionodon oligolinx

Slit eye shark Loxodon macrorhinus

Black spot shark Carcharhinus sealei

Black tip reefs shark Carcharhinus melanopterus

0.3 *

Hard nose shark Carcharhinus macloti

0.5 *

Oceanic white tip shark Carcharhinus longimanus

2.4 *

Common black tip shark Carcharhinus limbatus

White cheeks shark Carcharhinus dussumieri

Grey reef shark Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos

Family and species

0.1 *

Indonesian bird beak dogfish Deania cf. calcea

0.2 *

Dwarf gulper shark Centrophorus atromarginatus

0.5 *

Leaf scale Gulper Shark Centrophorus squamosus

0.8 *

Taiwan Gulper Shark Centrophorus niakung

1.1 *

Small fin Gulper Shark Centrophorus moluccensis

0.1 *

Large fin Gulper Shark Centrophorus cf. lusitanicus

0.4 *

Black fin Gulper Shark Centrophorus isodon

Centrophoridae

0.6 *

Big eye Six gill Shark Hexanchus nakamurai

0.7 *

Blunt nose Six gill Shark Hexanchus griseus

0.5 *

Sharp nose Seven gill Shark Heptranchias perlo

Indonesian spotted catshark Halaelurus maculosus

Indonesian Angel shark Squatina legnota

Squatinidae

0.1 *

* Wing head shark

Eusphyra blochii

Broad fin shark Lamiopsis temmincki

0.1 *

Sickle fin lemon shark Negatron acutidens

0.2 *

Spade nose shark Scoliodon laticaudus

0.4 *

White tip reef shark Triaenodon obesus

0.2 *

Australian sharp nose shark Rhizoprionodon taylori

0.3 *

Grey sharp nose shark Rhizoprionodon oligolinx

Slit eye shark Loxodon macrorhinus

Black spot shark Carcharhinus sealei

Black tip reefs shark Carcharhinus melanopterus

0.3 *

Hard nose shark Carcharhinus macloti

0.5 *

Oceanic white tip shark Carcharhinus longimanus

2.4 *

Common black tip shark Carcharhinus limbatus

White cheeks shark Carcharhinus dussumieri

Grey reef shark Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos

Family and species

Appendix 1. Continue

0.3 *

Traight-tooth weasel shark Paragaleus tengi

Sicklefin weasel shark Hemigaleus microstoma Mustelus cf manazo

0.2 Hemitriakis sp.1

Triakidae

0.1 *

Indonesian speckled catshark Haleolurus maculosus

Grey nurse shark Carcharias taurus

Odontaspididae

0.7 *

Tawny nurse shark Nebrius ferrugineus Orectolobuscf. ornatus

Orectolobidae

Western Longnose Spurdog Squalus nasutus

7.5 *

Indonesian Shortnose Spurdog Squalus hemippinis

Kite fin Shark Dalatias licha

0.1 *

Cookie cutter Shark Isistius brasiliensis

Family and species

0.3 *

Traight-tooth weasel shark Paragaleus tengi

Sicklefin weasel shark Hemigaleus microstoma Mustelus cf manazo

0.2 Hemitriakis sp.1

Triakidae

0.1 *

Indonesian speckled catshark Haleolurus maculosus

Grey nurse shark Carcharias taurus

Odontaspididae

0.7 *

Tawny nurse shark Nebrius ferrugineus Orectolobuscf. ornatus

Orectolobidae

Western Longnose Spurdog Squalus nasutus

7.5 *

Indonesian Shortnose Spurdog Squalus hemippinis

Kite fin Shark Dalatias licha

0.1 *

Cookie cutter Shark Isistius brasiliensis

Family and species

27 Appendix 1. Continue

0.2

Short-tail cownose ray Rhinoptera sp.1

0.1 *

Javanese cownose ray Rhinoptera javanica

Rhinopteridae

0.2 *

Mottled eagle ray Aetomylaeus maculatus

0.3 *

Banded eagle ray Aetomylaeus nichofii

0.1 *

Ornate eagle ray Aetomylaeus vespertilio

0.35 *

Longheaded eagle ray Aetobatos flagellum

0.5 *

* Whitespotted eagle ray

Aetobatus narinari

Japanese butterfly ray Gymnura japonica

1.3 *

Zonetail butterfly ray Gymnura zonura

0.7 *

Longtail butterfly ray Gymnura poecilura

Black spotted whipray Himantura astra

Indonesian cow stingray Dasyatis cf. Ushiei

0.5 Dasyatis sp.1 (grey, thorns)

0.2 *

Yellowmargin stingray Dasyatis cf. akajei

42

Family and species

0.2

Short-tail cownose ray Rhinoptera sp.1

0.1 *

Javanese cownose ray Rhinoptera javanica

Rhinopteridae

0.2 *

Mottled eagle ray Aetomylaeus maculatus

0.3 *

Banded eagle ray Aetomylaeus nichofii

0.1 *

Ornate eagle ray Aetomylaeus vespertilio

0.35 *

Longheaded eagle ray Aetobatos flagellum

0.5 *

* Whitespotted eagle ray

Aetobatus narinari

Japanese butterfly ray Gymnura japonica

1.3 *

Zonetail butterfly ray Gymnura zonura

0.7 *

Longtail butterfly ray Gymnura poecilura

Black spotted whipray Himantura astra

Indonesian cow stingray Dasyatis cf. Ushiei

0.5 Dasyatis sp.1 (grey, thorns)

0.2 *

Yellowmargin stingray Dasyatis cf. akajei

42

Family and species

0.35 Okamejei cf. powelli

0.3 *

Cute skate Okamejei cf. boesemani

0.4 *

Weng’s skate Dipturus sp.1

Rajidae

Indonesian shovelnose ray Rhinobatos penggali

0.75 *

Giant shovelnose ray Rhinobatos typus

0.9 *

Jimbaran shovelnose ray Rhinobatos jimbaranensis

Family and species

0.35 Okamejei cf. powelli

0.3 *

Cute skate Okamejei cf. boesemani

0.4 *

Weng’s skate Dipturus sp.1

Rajidae

Indonesian shovelnose ray Rhinobatos penggali

0.75 *

Giant shovelnose ray Rhinobatos typus

0.9 *

Jimbaran shovelnose ray Rhinobatos jimbaranensis

Family and species Appendix 1. Continue

Notes: DS = Deep Sea; Oc. = Oceanic; CCS = Coastal Continental Shelf. Total number of shark = 6,107 ind.; ray=13,527 ind.

INDONESIAN FISHERIES RESEARCH JOURNAL Instructions for Authors

Scope

Indonesian Fisheries Research Journal publishes research results on resources, oceanography and limnology for fisheries, fisheries biology, management, socio-economic and enhancement, resource utilization, aquaculture, post harvest, of marine, coastal and inland waters.

Manuscripts submission

Manuscripts submitted to the Journal must be original with clear definition of objective, materials used and methods applied and should not have been published of offered for publication elsewhere. The manuscripts should be written in English, in

double-spaced typing on one side A4-size white papers. Three copies of the manuscripts and a disk containing the manuscript file (s)

produced using MS Word must be submitted to the Managing Editor, Jl. Pasir Putih I Ancol Timur, Jakarta 14430, Indonesia,

E-mail: drprpt2009@gmail.com. There are no page charges for the manuscripts accepted for publications, unless otherwise indicated below.

Manuscripts preparation

- A title page should be provided which shows the title and the name(s) of the author(s). The author(s)’ position and affiliation should be written as footnotes at the bottom of the title page.

- Title should not be more than 15 words.

- Abstract summarizes the study is not more than 250 words. Keywords (3-5) must be provided and conform with Agrovocs.

- Introduction should concisely establish the relate to which the article concerns, the purpose and the importance of the work. Do not use any sub-headings.

- Materials and Methods should clearly and concisely describe the experiment with sufficient detail for independent repetition.

- Results are presented with optimum clarity with unnecessary detail. No same results should be presented in both tables and

figures. Tables (double spaced, same font size with text, no vertical line, lower case supercript letters to indicate, footnotes),

and illustration/figures should be printed on separate sheets and given arabic number consecutively. illustration/figures

should be submitted in original (1) and copied (2) forms and be sufficiently sharp for reproduction. 1 Photographs are

preferably black and white on glossy papers with good contrast. Color photographs of good quality are acceptable but the cost of reproduction must be paid for by the author(s). Exemption for bearing the cost can be sought from the publisher by written request.

- Conclusion should be short with regard to the title, objectives, and discussion of results.

- Acknowledgement, if necessary, should be kept minimum (less than 40 words).

- References should be cited in the text by the author(s)’ family or last name and date in one or two forms: Wang (1985) or

(Wang, 1985). For references with more than two authors, cite the first author plus et al. Full citation in alphabetical order is

required for the references list in the following style:

Sunarno, M.T.D., A. Wibowo & Subagja. 2007. Identifikasi tiga kelompok ikan belida (Chitala lopis) di Sungai Tulang Bawang,

Kampar dan Kapuas dengan pendekatan biometrik. Jurnal Penelitian Perikanan Indonesia. 13 (3): 1-14.

Sadhotomo, B. 2006. Review of environmental features of the Java Sea. Indonesia Fisheries Research Journal. 12 (2): 129-157.

Collins, A. 1977. Process in acquiring knowledge. In Anderson, R.C., Spiro, R.J. and Montaque, W.E. (eds.). Schooling and the

Acquisition of Knowledge. Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, New Jersey. p.339-363

Bose, A.N., Ghosh, S.N., Yang, C.T. and Mitra, A. 1991. Coastal Aquaculture Engineering. Oxford & IBH Pub. Co. Prt. Ltd., New

Delhi. 365 pp.

Smith, T.I.J. and Sandifer, P.O. 1983. Development of prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergil) farms in temperate climates:

Prospects and problems in the United States. In Roger, G.L., Day, D. and Um, A. (eds.) Proceedings of the First International

Conference on Warm Water Aquaculture - Crustacea. Brigham Young University, Laie, Hawaii, USA. p 109-126. Unpublished materials should not be used, except for thesis which is cited as follows:

Simpson, B.K. 1984. Isolation, Characterization and Some Applications of Trypsin from Greenland Cod (Gadus morhua).

PhD Thesis. Memorial University of New Foundland, St. John’s, New Foundland, Canada. 179 pp.

- Acronyms or uncommon abbreviations must be given in full with the first mentions; new abbreviations should be coined only for unwieldy name and should not be used at all unless the names occur frequently.

- Latin name and family of the species should be given besides its common name at first mention in the manuscript, and the common name only for the next mentions.

- SI Systems should be used for all measurements.