Enhancing the competitiveness of international rail freight services

Udo Sauerbrey

a; Stefan Mahler

aa

Railistics GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany

Abstract

The international rail freight business in Europe is still far behind its capabilities and the targets of all market opening initiatives by the EU. International rail transport in Europe increased but has not reached a significant market share during the last years if the whole of Europe is taken into account. One of the main factors influencing the competitiveness of rail freight are the costs of providing the services. The paper follows a market-oriented approach and analyses the costs of cross-border rail freight services on certain European corridors with a special focus on the influence of political and legal requirements on the costs. Several fields where a change in political and legal requirements can lower the costs of international rail freight services in Europe are identified. The paper shows therewith ways for an improvement of the competitiveness of rail freight in the European transport market.

Keywords: rail freight; competitiveness, costs; political and legal requirements

Résumé

Le secteur de transport de fret ferroviaire européen est toujours derrière ses possibilités et les objectifs de toutes les initiatives de la UE pour l’ouverture du marché. Si en prend en considération tous les pays Européens, le transport de marchandise ferroviaire international a grandi mais n’est pas arrivé à capter une part considérable du marché. Un des facteurs les plus influents sur la compétitivité sont les coûts pour offrir les services. Cet article suit une approche orientée marché et analyse les coûts des services ferroviaires transfrontaliers sur certains couloirs européens avec une focalisation spéciale sur l’influence des spécifications politiques et juridiques. Plusieurs domaines sont identifiés où un changement de ces spécifications peut diminuer les coûts des services ferroviaire international. L’article démontre par cela, des possibilités pour améliorer la compétitivité du fret ferroviaire sur le marché du transport européen.

1.Introduction

The international rail freight business in Europe is still far behind its capabilities and the targets of all market opening initiatives by the EU. International rail transport in Europe increased but has not reached a significant market share during the last years if the whole of Europe is taken into account. Before the European Community decided to make the railway more competitive the rail freight transport has witnessed a strong fluctuation in the last years. While in 2005 in the EU-25 just about 378 billion tkm got transported via rail the transported freight slightly decreased until 2012 to about 375 billion tkm (Eurostat2012).

However, on certain cross border corridors in Europe a highly competitive, successful and efficient service has been introduced. The success stories in Europe have several aspects in common. Technical, political, administrative, commercial and operational aspects are the basis for such positive examples. To increase the number of such corridors with efficient service provision would help customers such as the chemical, car or steel industry and consumer goods transport in several countries, would increase the added value of service providers, and would significantly improve the carbon footprint. Several interoperability and regulation initiatives implemented by the EU have not been able to create a full European-wide network of such corridors so far. This paper addresses the weaknesses of the system with special regard to administrative and legal requirements for rail freight. These requirements and their impact on the competitiveness, in terms of costs, of rail freight are analysed in-depth. The paper shows therewith possible ways for improving the competitiveness of rail freight services in Europe.

2.Methodology

One of the main factors reducing the competitiveness of rail freight are costs, Therefore this paper concentrates on the various costs of rail freight services. These are influenced by many factors, including technical, operational, political, administrative, legal and commercial aspects. Especially legal and political requirements often lead to higher costs and therefore have a negative impact on the competitiveness of rail freight compared to other modes. For this reason the paper focuses on the impact of political and legal requirements on the competitiveness of rail freight. The paper follows a clear market-oriented approach. A multi-step methodology was identified as best for this purpose.

As rail freight in Europe is to a large part concentrated on several main corridors and political and investment decisions on national as well as European level are often also based on a corridor principle (e.g. the TEN-T priority axes) the paper adopts a corridor oriented approach. Therefore first a brief introduction in relevant corridors is given.

Second step is the calculation and analysis of exemplary costs for typical rail freight services on selected corridors. This includes a break-down of the total costs into cost categories and the different national sections of the respective corridor. The cost break-down will serve as basis for further analysis later. A short review of previous research projects will also deliver input for the analysis. The next step is an in-depth analysis of the costs with special regard to costs induced by political and legal requirements. In order to identify the “weakest part of the chain” the analysis sheds light on the costs (influenced by political and legal requirements) which have the highest (negative) impact on the competitiveness of rail freight services. By this analysis the potential for enhancing the competitiveness of international rail freight services by a change in political and legal requirements

3.Corridors

3.1. TEN-T priority axes

higher line speeds, improvement for longer trains and the achievement of interoperability on the European rail network.

The European Union has defined a Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) and 30 priority axes based on their European added value. These cover the main European transport corridors and all different modes of

To manage the technical and financial implementation the Commission established the Trans-European Transport Network Executive Agency (TEN-T EA). The financing programme contains over 8 billion € for 2007-2015 and is therefore one of the most important financing means for financing transport infrastructure in Europe (European Commission 2012a). The total project costs from 2010-2020 for the priority axes (or projects) have been estimated to over 500 billion €, further investment will be needs until the expected completion of all projects in 2030.

The importance of rail in the generation of a Trans-European transport network can be seen in the fact that 18 out of the 30 priority projects are railway projects (TEN-TEA 2010). In the following the analysis concentrates on two priority axes (or projects). These two axes should be exemplary for the whole variety of rail freight in Europe. Therefore one axis with a deep international co-operation and many successful international rail freight services and one axis with a lower number of successful international rail services and a lower degree of international cooperation should be taken. Furthermore Western Europe as well as the new Middle and Eastern European member states should be taken into account. The two chosen priority axes 22 and 24 do fulfil best these requirements.

Priority Axis 22:

The priority axis 22 covers the corridor Athina-Sofia-Budapest-Wien-Praha-Nürnberg/Dresden. This corridor forms the most important railway link between Greece and the South East European member states on the one side and the rest of Europe on the other side. The aim is to improve the connectivity between these two parts of Europe. Therefore the project includes e.g. the modernization of railway sections and the optimization of railway stations. As the length of the axis is 3,575 km and it crosses seven member states the project has also a special place in the TEN-T network. Between 2007 and 2013 ultimately the project got funded with €21, 9 million and 47 % of the whole line is completed. The most problematic points of the axis are generally the cross-border sections. The public debt crisis severely affecting some member states along the axis has also adverse effects on the project. Despite this in 2012 some progresses could be achieved in Greece between Tithorea-Domokos and with some smaller station and line upgrading projects (European Commission 2012b).

Priority Axis 24

This Priority axis covers the railway axis Lyon/Genoa-Basel-Duisburg-Rotterdam/Antwerp with a length of 2,100 km crossing five member states and Switzerland in transit. This axis connects the North Sea ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp with parts of Germany, Switzerland, France, Northern Italy and finally the Mediterranean Basin in Genoa. The most important traffic on this route is intermodal transport mainly originating in one of the main ports along the axis. The corridor is one of the best working cross-border rail corridors in Europe even if large sections of the corridor still need to be upgraded. Today, on the corridor Genoa – Antwerp who is called by the EU as one of the six main axes in Europe, 28.5 billion tkm are transported. For 2020 an increase up to 56 billion tkm is estimated. The projects costs between 2007 and 2013 were nearly 500

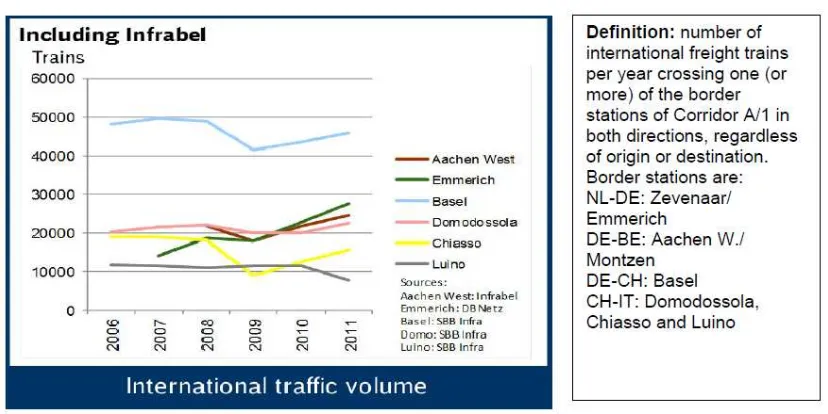

Fig. 1Volume of international freight traffic along priority axis 24

3.2 Interoperability

The achievement of interoperability is one of the main aims of the European rail policy. The implementation of ERTMS as one of the main contributors to better interoperability in Europe is also one of the priority projects of the TEN-T and there were six ERTMS-corridors defined. The corridors A and E are overlapping the priority axes 24 and 22 respectively. Even if significant progress has been achieved in the last years, there are still significant differences between the member states and the individual corridors in the deployment of the different components of ERTMS. Other factors of interoperability are for example the harmonisation of possible train lengths and weights.

3.3 Differences between the corridors

The analysed corridors show many differences not only in their infrastructural configuration but also in organisational issues directly influenced by political and legal requirements. These differences can, to some extent, explain the differences in the utilisation of the two corridors. The corridor Rotterdam-Genoa along priority axis 24 is one of the main arteries of the European rail freight network with a comparatively high modal share of rail and is therefore strongly used by cross-border freight trains. In contrast there are comparatively few international rail freight services along priority axis 22 leading to a lower market share of rail.

Along priority axis 24 the legal framework and the necessary procedures at border crossings cause less problems for international train operations and the infrastructure for interoperability (ERTMS etc.) is further developed than along the priority axis 22. Furthermore the liberalisation of rail freight and therefore the intra-modal competition is further developed in the countries along the priority axis 24. According to the liberalisation index for rail freight 2011of IBM and Deutsche Bahn the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany are in position 2, 3 and 4 with Switzerland and Italy also among the advanced group. Several countries along the priority axis 22 are among the bottom group in Europe (e. g. Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Greece) (IBM 2011).

4.Calculation and analysis of exemplary costs for rail freight services

usage of this asset will decrease and the costs will increase resulting in lower competitiveness of rail freight. In the following exemplar trains on two corridors are calculated showing the effects of those political decisions.

The costs used in this article are based on actual market prices gained in various projects in European rail freight and through a continuous observation of the European rail freight market which was published in parts (e.g NEA 2008). Next to observed market prices also the published prices of infrastructure managers and other service providers are taken as basis. Calculated are exemplar costs for running a train on the respective corridor. The actual costs of individual train operators and specific trains will naturally vary to some extent, but the calculated costs represent an average and, more importantly, show a realistic and average distribution of the individual cost components.

Generally the costs of rail freight services can be split into the following main cost-components:

Locomotive costs

Wagon costs

Access costs

Energy costs

Labour costs

In addition to these categories there are overhead costs of the operator which are often calculated as percentage of the remaining total costs.

The first corridor to be analysed is the corridor Rotterdam- Busto Arsizio, crossing the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and Italy along priority axis 24. The second corridor runs from Antwerp to Vienna crossing Belgium, Germany and Austria.

The overall costs for a round trip on the first corridor are 33,195.33 Euro. In Detail the costs have to be divided into costs per country and Kilometre to get a realistic picture of the costs implied by political and legal requirements. As the corridor Rotterdam-Northern Italy is one of the most heavily used corridors for intermodal rail transport in Europe the calculation is carried out for a container train between the port of Rotterdam (RSC Waalhaven) and the intermodal terminal of Busto Arsizio near Milan. The calculation of the individual cost categories is described below. As example for the costs of missing interoperability it is assumed that in the Netherlands and Italy special Diesel locomotives are necessary. On the Dutch Betuwe-line there was long time no electric locomotives available capable to run with 25 kV AC and the installed train control system. In Italy again a diesel locomotive was chosen, due to the fact that at the beginning of liberalisation there was a lack of licensed electric locomotives capable of running to Switzerland and Germany. This was especially true for open access operators on the Italian market (Meanwhile the situation has significantly improved and the use of electric locomotives is standard).

The locomotive costs comprise the costs of depreciation, interest, insurance, and maintenance (again divided in fix and running maintenance). All costs were calculated as annual costs with actual investment costs for appropriate locomotive types and typical industry values (e.g. an insurance rate of 2.2% of investment costs). For Germany and Switzerland a standard AC locomotive able to run in Germany, Switzerland and Austria was taken. A major aspect is the calculated number of locomotives needed for such a transport. This number depends on the utilization and performance of the asset. The more kilometres the locomotive is able to haul the train, the lower the costs for the asset.

In the example the need for locomotives based on 260 trains per year and direction was calculated with average productivity figures. The calculation showed the need for one locomotive each in the Netherlands and Italy and two locomotives for Germany and Switzerland together. The calculated costs rose to about 471,000 € in the Netherlands, 865,000 € in Germany and Switzerland, and 393,000 € in Italy.

plan of the railway undertaking but its optimization is limited by differences on technical level, by infrastructure management principles and by national restrictions on administrative level.

The calculation of wagon costs was also based on actual purchasing prices of wagons and take into account depreciation, interest, insurance, and maintenance. Two different types of typical intermodal wagons were chosen (5x Sgns and 15xSggmrss), this allows for 75 TEU to be transported. The resulting length takes also the existing restrictions on the corridor into account. To carry out 260 round trips per year three wagon sets were needed, so a total of 15 Sgns and 45 Sggmrss had to be taken into account. The total wagon costs are calculated as about 552,000 €.

The next cost category are infrastructure costs. These were calculated based on the respective access charges of the different infrastructure managers and take the length of the trains and the maximum weight into account. The access charges for one way in the Netherlands were 125.08 €, in Germany 2,704.48 €, in Switzerland 1,218.00 € and in Italy 206.84 €.

In the Netherlands and Italy diesel costs based on the diesel consumption (in litre/km) of the used locomotive type were computed for the calculation of energy costs whereas in Germany and Switzerland the consumption of electric energy in kWh/km (Germany) and kWh/ton in Switzerland. The calculated total energy costs for one way were 371.05 € (Netherlands), 1,872.75 € (Germany), 577.58 € (Switzerland) and 202.25 € in Italy.

The last main cost category are labour costs. As all administrative staff and staff for additional services are included in overhead costs, the labour costs of train drivers are taken here. The costs were calculated based on the average salaries per year which range from 20,400 € in Italy to 48,299 € in Switzerland. Other input factors were the number of working hours per year, the labour costs factors and average productive hours per working hour, which showed also considerable difference between the affected countries. In Italy it had to be taken into account that two drivers were required. The resulting labour costs per hour range from 33.20 € to 71.54 € in Switzerland.

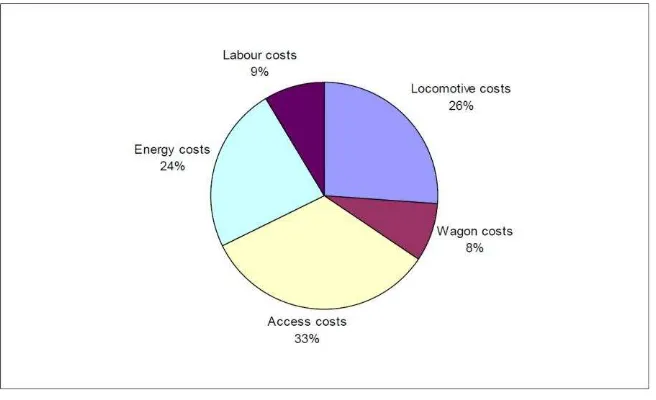

An overview on the proportion of the different cost factors (excluding overhead) can be found in the following figure. It is clearly visible that access costs have the highest share in the total costs followed by locomotive costs and energy costs. Wagon costs and labour costs have a comparative small share in total costs.

Fig. 2: Overview costs for the corridor Rotterdam – Busto Arsizio

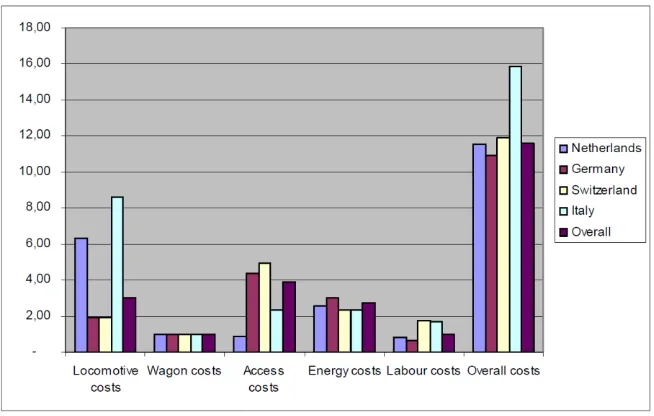

the countries as the same wagon set is used in all countries. The energy costs are higher in Italy and the Netherlands due to the use of diesel locomotives in these countries. The access costs per km also widely differ between the individual countries.

Fig. 3: Divided costs per kilometre per country

The second corridor runs from Antwerp North in Belgium to the central marshalling yard in Vienna, Austria. The total costs for one round trip are 29,844.30 Euro. Again the costs are broken down into costs per country and kilometre. Antwerp is one of the main ports for liquid bulk in Europe and there are considerable flows of liquid bulk between the Eastern member states of the EU and the port of Antwerp via the marshalling yard in Vienna. Therefore a train for liquid bulk was chosen for the calculation. This was carried out with the same methodology as for the Rotterdam-Busto Arsizio corridor.

For the calculation of locomotive costs a diesel locomotive was assumed for the section in Belgium and one electric loco for Germany and Austria. For 260 round trips per year one diesel loco is sufficient, but there is a need of two electric locomotives. The total costs rise to 471,000 € per year for the Diesel loco in Belgium and 828,000 € for the standard AC electric locos for Germany and Austria. Again the costs per unit (train kilometre are significant, see fig. 4) The wagon costs for three wagon sets (54 tank wagons type Zans in total) are about 524,000 € per year.

The access charges were also calculated based on the Network statements of the respective Infrastructure

Managers and differ considerably between 372.65 € for one way in Belgium, 1,192.72 € one way in Austria and

2,229.80 € one way in Germany. The energy costs are calculated in litre/km (Belgium) and kWh/km (Germany, Austria). For one way the energy costs are about 346.99 € in Belgium, 2,204.87 in Germany and 720.71 in Austria. The labour costs (train driver) per effective hour are highest in Belgium (56.27 €). The costs in Germany and Austria are quite close (33.20 € and 34.83 respectively). The difference compared to Belgium is mainly due to the higher annual salary in Belgium.

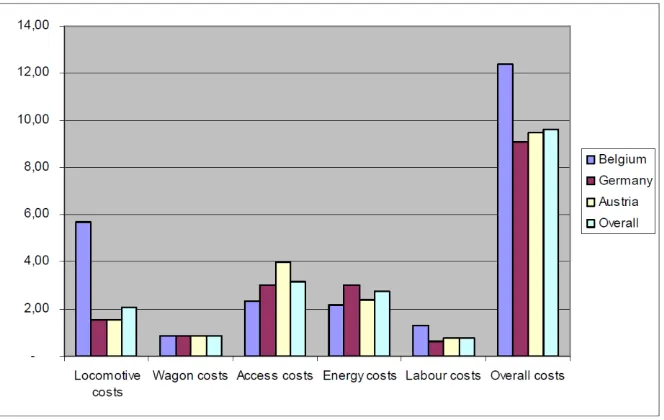

Fig. 4: Overview costs for the corridor Antwerp North – Vienna

The same break down of costs as for the first corridor shows that Belgium has the highest cost per km and Germany has the lowest, but the difference to Austria is only marginal. Mainly the locomotive costs are higher for the Belgian section which can partly be explained by the lower usage of the locomotive for the comparable short section in Belgium. Also labour costs are higher in Belgium. In contrast access charges and energy costs are higher in Austria and Germany.

Fig. 5: Divided costs per kilometre per country

5.Review of previous research projects

demonstration and implementation of an innovative and market tested rail freight service on the corridor Rotterdam-Constanta (Janic 2012). The CREAM project aimed at the development, demonstration and implementation of an innovative demand and customer driven intermodal rail service between Western Europe and South Eastern Europe and further to Turkey and the Middle East (Janic 2012). Both projects had therefore a similar scope. The main differences were that REATRACK comprised independent private rail operators whereas CREAM was mainly driven by incumbent rail operators of the relevant countries. RETRACK was also not only focused on intermodal rail transport.

The RETRACK project identified network incompatibilities, regulatory diversity and operational disparities between the different countries involved as major risks for the operation of an international train service on the corridor (Ludvigsen 2011). These factors are directly influenced by political and legal requirements. The CREAM project also analysed different factors related to political and legal requirements. One main factor was the legal framework and necessary processes at border crossings which have also a strong influence on the necessary border crossing times and therefore on the costs of the rail freight service. The project analysed several border crossings along the corridor and defined categories from A to C relating to problems at border crossings (HaCon 2012). Most border crossings with few problems are in the western parts of the corridor whereas the more problematic border crossings are concentrated in South Eastern Europe.

6.Analysis of costs influenced by political and legal requirements

Political and legal requirements have a considerable influence on the costs of rail freight services. This is true for all five cost categories calculated in chapter 4: locomotive costs, wagon costs, access costs energy costs and labour costs. Main issue, however, is the utilisation of assets which depends on several aspects, e.g. logistical concepts, regulations and the possibility of interoperability.

In the following a few examples out of the calculations in chapter 4 are presented. Examples of the influence on locomotive costs are shown by the calculation with diesel locomotives in the Netherlands and Italy in the first corridor. In the Netherlands there was a political decision to build a new freight railway line from the port of Rotterdam towards the German border (Betuwe line). This line was equipped with 25 kV AC in contrast to the DC system in use elsewhere in the Netherlands. In addition the line was equipped with ETCS as train control system. On the long run these decision facilitate the interoperability of the European rail system, but in short term made the use of diesel locomotives necessary on the Dutch section as there were no suitable electrical locomotives available. Therefore the locomotive costs rose for the Dutch section.

The use of diesel locomotives in Italy has a different background. In Italy the legal requirements for licencing electrical locomotives were difficult to comply with for new independent rail operators. Therefore only the incumbent had electrical locomotives all other operators needed to use diesel locomotives where a licensed type was available. This leads to higher costs for independent operators.

The calculation of access costs per kilometre in chapter 4 shows considerable differences between the different countries. The costs per kilometre in the Netherlands are for example less than a quarter of the costs per kilometre in Germany and Switzerland and the costs in Italy are still about half of the German and Swiss costs. Besides some smaller differences in the cost factors in the individual countries the access costs are mainly defined by the question which extent of the total costs of the infrastructure are to be covered by the users and to which extent by the government. In the Netherlands a high share of total costs is financed by government resulting in very low access charges whereas in Germany a larger part has to be covered by the users resulting in comparably high access charges.

In labour costs a possible example is the influence of legal requirements in Italy making two drivers necessary whereas all other countries only require one. As a result the labour costs per kilometre in Italy are about double the costs in Germany and the Netherlands.

that the use of different locomotives on the different national sections are a considerable cost factor due to the need for more locomotives and the lower productivity of the locomotives. Problems at border crossings are more difficult to calculate. The higher administrative effort at border crossings due to a difficult legal framework and poor cross-border coordination would be part of the general overhead costs which are difficult to calculate exactly for an individual train run. Longer border crossing times have an influence on all time-dependent costs of the rail service, e. g. the wagon rent and labour costs. On the other hand they have an impact on the overall transport time of goods and therefore on the attractiveness of the service for customers.

7.Conclusion

As the analyses above have shown political and legal requirements have a high impact on the costs of rail freight services. Directly and indirectly they influence all different operational and administrative costs. There are several fields where a change in political and legal requirements can lower the costs of rail freight services and therefore improve the competitiveness which can result in modal shift to rail.

One major aspect are the requirements for licensing of locomotives and national requirements making interoperability more difficult. These requirements can make the use of different locomotives in the individual countries necessary. Therefore not only more locomotives are necessary but also the usage of the individual locomotives is lower resulting in locomotive costs having a higher share in the total costs.

Another point are access costs which are mainly defined by the political decision to which extent the total costs of the infrastructure are to be paid by the railway operator as user.

It is therefore important that political decisions on international and national level regarding rail related technical and infrastructural decisions and regarding the respective administrative procedures are done with respect to the impact on rail transport costs, especially in the freight sector. The market usually has very limited margins and even a small change can cause the non-competitiveness of rail transport projects.

References

European Commission 2012a: European Commission; Trans-European Transport Network Executive Agency – A brief overview; Brussels; 2012

European Commission 2012b: European Commission; Annual Report of the coordinator – Priority Projects 22 Gilles Savary; Brussels, 2012

Eurostat 2012: Eurostat database, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/statistics/search_database, last, access 09.12.2013

Hacon 2012: HaCon; The CREAM project – Technical and operational innovations implemented on a European rail freight corridor; Hannover; 2012

IBM 2011: IBM, Kirchner, Prof Dr. Dr. Dr. h.c. Christian; Rail liberalisation index 2011, Brussels, 2011

Janic 2012: Janic, Dr. Milan; Retrack Deliverable 9.2: Recommendations from comparison with evaluation results of other corridor services; 2012

Ludvigsen 2011: Ludvigsen, Johanna: Retrack Deliverable 3.2: Outline of business plan; 2011

NEA 2008: NEA, Railistics; Cost and performance of European rail freight transportation; Zoetermeer 2008