T

he question of whether men and women in the accounting profession view ethics and communication differently has been raised before, but the importance of these skills to the profession combined with the changing demographic profile of the profession make it time to reexamine the issue. In their 2006 article, “Gender Imbalance in Accounting Academia,” Charles Jordan, Gwen Pate, and Stanley Clark found that the propor-tion of female accounting administrators and deans had increased significantly between 1994 and 2004. The percentage of female accounting program administrators increased from 7.1% to 16.7 %, and the percentage offemale deans increased from 2.6% to 14.6%. In 2004, women held 24.5% of all tenure-track accounting facul-ty positions at the institutions surveyed, while the ratio of women to men in the accounting practice or account-ing students in the classroom was closer to 50%.1If there is a difference in how male or female accounting faculty and department chairs perceive or apply ethics and communication in their teaching, it will soon begin to affect the profession.

Professional organizations have stressed that both ethics and communication are critical to accounting. For example, a recent article in Management Accounting Quar-terlyprovided practitioners with an instrument to help

Do Male and Female

Accountancy Chairs

Perceive Ethics and

Communication the

Same?

A

SURVEY OF MALE AND FEMALE ACCOUNTING PROGRAM CHAIRS EXAMINESTHE EFFECTS THAT THEIR GENDER HAS ON THREE ISSUES

:

THE PERCEPTION OF THE NEEDTO STUDY ETHICS AND COMMUNICATION SKILLS IN THE BUSINESS AND ACCOUNTING

CURRICULA

,

THE PERCEIVED AMOUNT OF ACTUAL CLASS TIME SPENT AND THEIDEAL CLASS TIME THAT SHOULD BE SPENT ON THESE CONCEPTS

,

AND WHERE ETHICSSHOULD BE TAUGHT IN THE ACCOUNTING CURRICULUM

.

measure and improve ethical perceptions in their orga-nizations.2AACSB International (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business) strongly rec-ommends that accredited schools include ethics educa-tion in the business curriculum, and the Naeduca-tional Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) advanced a proposal in 2005 to require a separate course in ethics within the accounting curriculum in addition to the one required in the business curriculum. Although the proposal was later withdrawn, it indicates the increasing concern for including ethics instruction in accounting education. Going back to 1989, the then Big Eight accounting firms published a paper that emphasized the importance of communication skills within both the business and accountancy curriculum.3 Finally, in its Vision Statement for 1998, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) included communication as one of the seven personal core competencies required of entry-level accountants.4

The critical issue that remains for the accounting profession is whether these concerns have been imple-mented within accounting education programs and how uniform the implementation has been from institution to institution. In a previous study, we examined whether accreditation (AACSB or non-AACSB) or insti-tutional charter (private or public) affected how pro-gram chairs perceived the importance of ethics education and its implementation.5In this article, we will examine what effect, if any, an accounting chair’s gender has on his or her perceptions of ethics and com-munication and how these skills are taught in account-ing and general business programs.

RE L AT I O N S H I P O F GE N D E R T O ET H I C S A N D CO M M U N I C AT I O N

Previous studies on gender differences have had mixed results. Much of the research has used the defining issues test (DIT) to assess moral development. Michael Shaub found that female auditors in senior and manage-ment roles had higher moral developmanage-ment scores than male auditors in the same positions.6Using a sample of auditors from large, midsize, and small auditing firms, John Sweeney found that the females in senior and management auditor roles also had higher moral devel-opment than their male counterparts.7Richard Bernardi

and Donald Arnold concurred, finding that female man-agers in five large public accounting firms had a higher level of moral development than male managers.8Yet other studies did not find differences based on gender.9

Using business ethics vignettes rather than the DIT, Jeffrey Cohen, Laurie Pant, and David Sharp found that women had consistently different ethical evalua-tions, intention, and orientation than men and were more likely than males to view questionable behavior as

more unethical.10Don Giacomino and Tim Eaton

found significant differences in the value systems of male and female accounting alumni: Women were more oriented to serving others (vs. serving self) and using

more moral (vs. competence) means than men.11

In communication, women are recognized as display-ing a higher awareness of interpersonal and listendisplay-ing skills compared to men. Women view conversation as relationship building, while men view conversation as a means to gain respect and knowledge.12These ap-proaches lead to differences in interpersonal communi-cation and listening styles. Women are more apt to recognize problems in relationships before men do. Women also give more listening cues and listen more to

men than men listen to women.13Women are also better

than men at decoding nonverbal communication signals.14

TH E SU R V E Y

We set out to discover if these differences in the per-ception and practice of ethics and communication occur within the academic environment as well as in profes-sional practice. To do so, we surveyed the chairs of the 530 largest accountancy programs in North America. (Programs chosen had five or more faculty members.) A total of 122 usable responses were received, a response rate of 23%, and the results were subjected to statistical analysis to determine if there were significant differ-ences in the responses based on gender.

and what they felt would be the ideal percentage of class time to devote to the study of these areas. Finally, chairs were asked where in the accounting curriculum ethics should be taught.15

The Importance of Ethics and Communication

The survey revealed that there are no gender-based dif-ferences in the perceived importance of ethics for either the accounting or business curricula (see Table 1). Both male and female chairs believe the inclusion of ethics in the accounting and general business curricula is important. All means for ethics are over 4.0 (“of great importance”) on a five-point scale. Regardless of gen-der, ethics is perceived as more important in the accounting curriculum than in the business curricu-lum (p<0.01), a statistically significant difference.

There are no significant gender differences in the perceived importance of communication skills (speaking, writing, listening, interpersonal communi-cation, and technological communication) in either the accounting or general business curricula. Both male and female chairs believe these skills are impor-tant. The means for both sexes are over 4.0 for all areas except listening. Regardless of gender, speaking is considered more important in the business curricu-lum (p<0.05), and listening (p<0.05) and technologi-cal (p<0.01) communication are perceived as more important in the accounting curriculum.

Class Time Spent on Ethics and Communication

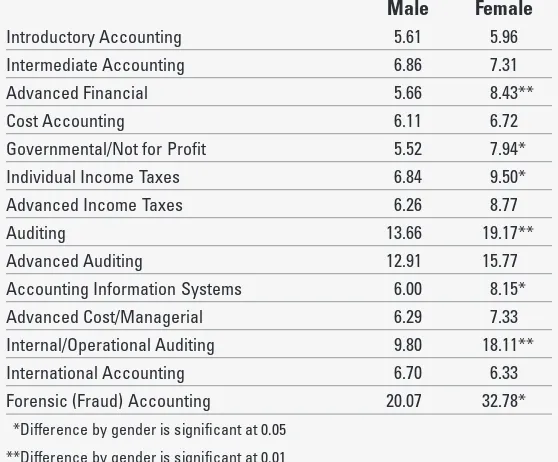

Respondents were asked the percentage of actual class time that is spent on ethics in 14 identified

accounting classes, as well as what they considered the ideal percentage of class time that should be spent on ethics in these classes (see Table 2). In 13 of the 14 accounting classes listed, female chairs perceive spend-ing more actual time on ethics than male chairs do. (The lone exception is International Accounting.) These differences are statistically significant for seven of the 14 courses (50%).

When looking at the ideal amounts of time chairs felt

Table 1:

The Importance of Ethics and Communication Instruction in

Accounting and Business Curricula

Accounting Curriculum Business Curriculum

Male Female Male Female

Ethics 4.25 4.42 4.10 4.29

Speaking 4.17 4.11 4.24 4.30

Writing 4.38 4.37 4.33 4.37

Listening 4.17 3.96 4.10 3.81

Interpersonal 4.22 4.04 4.16 4.04

Technological 4.30 4.19 4.06 4.11

Scale: 1=no importance, 5=maximum importance

Table 2:

Actual Percentage of Class Time

Spent on Ethics in Accounting

Courses

Governmental/Not for Profit 5.52 7.94*

Individual Income Taxes 6.84 9.50*

Advanced Income Taxes 6.26 8.77

Auditing 13.66 19.17**

Advanced Auditing 12.91 15.77

Accounting Information Systems 6.00 8.15*

Advanced Cost/Managerial 6.29 7.33

Internal/Operational Auditing 9.80 18.11**

International Accounting 6.70 6.33

Forensic (Fraud) Accounting 20.07 32.78*

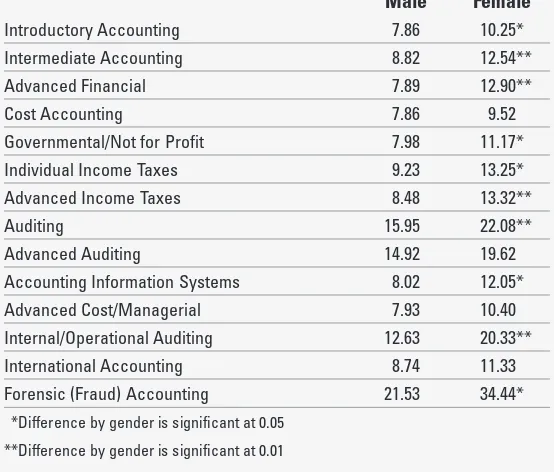

should be spent on these topics, the mean scores of female chairs is higher than those of male chairs for all classes (see Table 3). These differences are statistically significant for 10 of the 14 classes (71%).

In addition to ethics, respondents were asked the per-centage of actual time spent on the communication skills (speaking, writing, interpersonal skills, listening, and technology) in the accounting and general business curricula. They were also asked what would be the ideal percentage of class time to spend on each of these skills.

There are no statistically significant differences by gender for the percentage of actual or ideal amount of time that should be spent on these skills in the account-ing curriculum. In the general business curriculum, how-ever, statistically significant differences by gender were found for both the actual and ideal percentage of class time spent on listening (p<0.01) and interpersonal skills (p<0.05). Compared to their male counterparts, female chairs perceive spending more actual time in these areas and feel that a higher percentage of time should ideally be spent on listening and interpersonal skills.

Where in the Curriculum

Respondents were asked to choose from six options related to where they believed ethics education should be taught: (1) integrated throughout the accounting cur-riculum, (2) as a separate class required for all account-ing students, (3) as both a separate class required of accounting students and integrated throughout the accounting curriculum, (4) not required for undergradu-ate accounting majors, (5) as a requirement in the gen-eral business core, or (6) not required for the gengen-eral business core.

There were no gender differences on where ethics should be taught. Most chairs (66.7% of female chairs, 65.9% of male chairs) felt that ethics should be integrat-ed throughout the accounting curriculum. Several chairs (26.7% of female chairs, 30.6% of male chairs) felt that ethics should be a separate course for accounting majors as well as integrated throughout the curriculum.

SU R V E Y IM P L I C AT I O N S

The findings of this study have several implications for the field. Although there are no gender differences in the perception of how important ethics and communi-cation skills are for the accounting and business cur-riculum, there are statistically significant differences related to how these topics should be implemented throughout the curricula. Female chairs perceive spending significantly more actual time on ethics and communication in 50% of the identified accounting courses, and more female chairs than male chairs feel a higher percentage of class time should be spent on ethics. Compared to male chairs, female chairs also perceive that statistically significant more actual time is spent—and ideally a higher percentage of class time is needed—in teaching the communication skills of lis-tening and interpersonal communication in the general business curriculum.

Most chairs agree that ethics instruction should be integrated into the accounting curriculum rather than having a stand-alone ethics course. The differences in the perception of the ideal time that should be spent on these topics is particularly critical because the notion of ideal time represents how the various chairs want to implement these concepts within their curricula. With these differences in perception, implementation could

Table 3:

Ideal Percentage of Class Time Spent

on Ethics in Accounting Courses

Male Female

Introductory Accounting 7.86 10.25*

Intermediate Accounting 8.82 12.54**

Advanced Financial 7.89 12.90**

Cost Accounting 7.86 9.52

Governmental/Not for Profit 7.98 11.17*

Individual Income Taxes 9.23 13.25*

Advanced Income Taxes 8.48 13.32**

Auditing 15.95 22.08**

Advanced Auditing 14.92 19.62

Accounting Information Systems 8.02 12.05*

Advanced Cost/Managerial 7.93 10.40

Internal/Operational Auditing 12.63 20.33**

International Accounting 8.74 11.33

Forensic (Fraud) Accounting 21.53 34.44*

vary between programs. Certainly students in programs with female chairs have a greater chance of receiving more instruction in ethics than those in programs with male chairs.

Second, these findings reinforce the need for profes-sional organizations such as AACSB International and NASBA to consider establishing minimum standards regarding the percentage of class time and/or hours of instruction that accounting programs devote to ethics and communication. This will help ensure that all stu-dents receive adequate instruction in ethics and com-munication skills. It is no longer enough for these professional organizations to continue stating that ethics and communication skills instruction are simply “important.” The results of this survey show that inter-pretations of importance can and do vary. There is a need for these professional organizations to quantify what they mean by “important” in terms of hours and standards.

Finally, this study demonstrates that the gender dif-ferences in the perception of ethics and communication skills evident in the field also occur in accounting edu-cation. As more women continue to enter the academic accounting profession and professional practice, these differences will become more pronounced and should continue to be studied. ■

Jacqueline J. Schmidt, Ph.D., is a professor of communica-tion at John Carroll University, Cleveland, Ohio. You can contact her at schmidt@jcu.edu.

Roland L. Madison, Ph.D., is a professor of accountancy at John Carroll University, Cleveland, Ohio. You can contact him at rmadison@jcu.edu.

EN D N O T E S

1 Charles Jordan, Gwen Pate, and Stanley Clark, “Gender Imbalance in Accounting Academia: Past and Present,” Journal of Education for Business, January/February 2006, pp. 165-169. 2 Sandra B. Richtermeyer, Martin M. Greller, and Sean R.

Valen-tine, “Organizational Ethics: Measuring Performance on This Critical Dimension,” Management Accounting Quarterly, Spring 2006, pp. 23-30.

3 D.R Kullberg (Arthur Andersen & Co.), W.L. Gladstone (Arthur Young), P.R. Scanlon (Coopers & Lybrand), J.M. Cook (Deloitte Haskins & Sells), R.J. Groves (Ernst & Whinney), L.D. Horner (Peat Marwick & Co.), S.F. O’Malley (Price Waterhouse), and E.A. Kangas (Touche Ross), “Perspectives on Education: Capabilities for Success in the Accounting

Pro-fession,” American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, New York, N.Y., 1989.

4 American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, “Focus on the Horizon: CPA Vision—2011 and Beyond,” Journal of Accountancy, December 1998 Special Insert, pp. 25-72. 5 Roland L. Madison and Jacqueline J. Schmidt, “Survey of

Time Devoted to Ethics in Accountancy Programs in North American Colleges and Universities,” Issues in Accounting Edu-cation, May 2006, pp. 99-109.

6 Michael K. Shaub, “An Analysis of the Association of Tradi-tional Demographic Variables with Moral Reasoning of Audit-ing Students and Auditors,” Journal of Accounting Education, Winter 1994, pp. 1-26.

7 John T. Sweeney, “The Moral Expertise of Auditors: An Exploratory Analysis,” Research on Accounting Ethics, volume 1, Marc J. Epstein, John Gardner, and Lawrence A. Ponemon, eds., Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 1995, pp. 213-234. 8 Richard A. Bernardi and Donald F. Arnold, Sr., “An

Examina-tion of Moral Development within Public Accounting by Gen-der, Staff Level, and Firm,” Contemporary Accounting Research, Winter 1997, pp. 653-658.

9 Lawrence A. Ponemon and David R.L. Gabhart, Ethical Rea-soning in Accounting and Auditing, Research Monograph No. 21, CGA-Canada Research Foundation, Vancouver, Canada, 1993; and Judy S. Tsui, “Auditors’ Ethical Reasoning: Some Audit Conflict and Cross Cultural Evidence,” International Journal of Accounting, volume 31, issue 1, 1996, pp. 121-133.

10 Jeffrey Cohen, Laurie W. Pant, and David J. Sharp, “The Effect of Gender and Academic Discipline Diversity on the Ethical Evaluations, Ethical Intentions, and Ethical Orienta-tion of Potential Public Accounting Recruits,” Accounting Horizons, September 1998, pp. 250-270.

11 Don E. Giacomino and Tim V. Eaton, “Personal Values of Accounting Alumni: An Empirical Examination of Differences by Gender and Age,” Journal of Managerial Issues, Fall 2003, pp. 369-382.

12 Deborah Tannen, You Just Don’t Understand, Harper Collins, New York, N.Y., 1990.

13 Joseph A. DeVito, The Interpersonal Communication Book, 11th edition, Allyn & Bacon, Boston, Mass., 2007.

14 Lea P. Stewart, Pamela J. Cooper, Alan D. Stewart, and Sheryl A. Friedley, Communication and Gender, 4th ed., Allyn & Bacon, Boston, Mass., 2003.