COMMENTARY

Economic considerations of privately owned parks

Jeffrey A. Langholz

a,*, James P. Lassoie

b, David Lee

c, Duane Chapman

caProgram in International En6ironmental Policy,Monterey Institute of International Studies,MIIS/IEP,425 Van Buren St., Monterey,CA 93940, USA

bDepartment of Natural Resources,Cornell Uni6ersity,Ithaca,NY, USA

cDepartment of Agricultural,Resource,and Managerial Economics,Cornell Uni6ersity,Ithaca,NY, USA

Received 20 January 1999; received in revised form 8 July 1999; accepted 27 October 1999

Abstract

Privately owned parks continue to proliferate worldwide. Their rapid expansion represents an important yet little understood private sector incursion into an activity long dominated by governments. This paper examines economic issues surrounding establishment and operation of privately owned natural areas. We interviewed owners of 68 private parks in Costa Rica to learn more about reserves’ underlying economics. Key findings include: (1) private parks require an expanded definition of optimal reserve size — one in which quality of protection takes precedence over quantity of land protected; (2) profit was a powerful motivator behind private reserve operation, even though many owners did not rely on their reserves for revenue generation; and (3) an important non-market value of private parks was the high bequest value owners placed on them. Last, we identify key information gaps that resource economists can help fill regarding this increasingly popular conservation tool. The analysis contributes to our understanding of private reserves on both theoretical and empirical levels. It should be of interest wherever biodiversity remains threatened, wherever new conservation partners are being sought, and wherever private reserves are being established, which includes most of the industrialized and developing world. © 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Conservation; Ecotourism; Private parks; Protected areas; Stewardship

www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

1. Introduction

The alarming pace of habitat destruction neces-sitates development of innovative approaches for

in situ biodiversity conservation (e.g. Western and Pearl, 1989; Wilson, 1989; McNeely et al., 1990). Evidence suggests that current approaches to bio-diversity protection are more difficult and less successful than was originally hoped (Wells and Brandon, 1992; Kramer et al., 1997; Langholz, 1999b). Even worse, a shockingly high percentage * Corresponding author.

E-mail address:[email protected] (J.A. Langholz)

of parks are underprotected, with many existing on paper only (Machlis and Tichnell, 1985; Amend and Amend, 1992; Van Schaik et al., 1997; Brandon et al., 1998). Finally, even if public parks were well protected, they still would leave more than 93% of the world’s land area unpro-tected (Western et al., 1993; World Resources Institute et al., 1998). It is clear we need to explore new conservation strategies for protecting vast amounts of the land that will never be a public park. As Western (1989) notes, ‘‘land be-yond parks is the best hope and biggest chal-lenge’’ for conservation.

One option beyond public parks is the privately owned nature reserve. Private nature reserves have been quietly proliferating throughout the world, yet little is known about them. Authors have begun to mention their existence, but have provided little detail (e.g. Adams, 1962; Zube and Busch, 1990; Barborak, 1995; Murray, 1995; Bor-rini-Feyerabend, 1996; Langholz, 1996b; Schelhas and Greenberg, 1996; Uphoff and Langholz, 1998). A few authors have done case studies high-lighting various aspects of specific reserves (e.g. Horwich, 1990; Glick and Orejuela, 1991; Echev-erria et al., 1995; Alyward et al., 1996; Brandon, 1996; Wearing and Larsen, 1996; Yu et al., 1997). On the international scale, three researchers have conducted mail surveys on private reserves, each designed to confirm and build upon previous

find-ings (Alderman, 1994; Langholz, 1996a;

Mesquita, 1999). The 63 reserves in Alderman’s study, for example, were protecting more than one million hectares of ecologically valuable habi-tat. Langholz (1999a) has provided a proposed category system for private reserves worldwide that captures their immense diversity. The typol-ogy includes NGO-owned reserves such as those owned by The Nature Conservancy, as well as nine other distinct types of private reserves. The study also sheds light on varying levels of ‘protec-tion’ provided by reserves. Occupying one ex-treme, for example, were strict nature reserves where all forms of human disturbance were pro-hibited. Such reserves typically enjoyed legal recognition as wildnerness areas and corre-sponded to IUCN Category IA and IB protected areas. On the other extreme were areas devoted

primarily to human activity such as extraction of food, fiber, and fuel. The largest group of private reserves, however, existed between the two ex-tremes, pursuing biodiversity objectives in con-junction with relatively non-consumptive human activity such as ecotourism (IUCN Category IV). Additional studies have confirmed the private sector’s increasingly important role in biodiversity conservation (Edwards, 1995; Merrifield, 1996).

Even the World Conservation Union has

launched projects to learn more about this rela-tively new conservation tool. In effect, what Dixon and Sherman (1990) called ‘‘...a small but important development in protected area manage-ment’’ a few short years ago has evolved into a major new direction in conservation.

Despite the sudden proliferation of private re-serves, and studies of them, we still know very little. Most articles mention them only briefly. Worse, we know practically nothing of their un-derlying economics. Granted, economists have an-alyzed private provision of various goods and services, including prisons, police protection, garbage collection, schools, and so on (e.g. Shi-chor, 1995; Schmidt, 1996; Vickers and Yarrow, 1988), and they have recently started making con-tributions to the protected areas literature in gen-eral (e.g. Dixon and Sherman, 1990; Pearce and Moran, 1994; Barbier et al., 1995). Economists have yet, however, to contribute to the emerging private parks phenomenon. Given limited public resources available for conservation, and growing interest in private sector initiatives, it is impera-tive that we begin to explore key economic issues surrounding privately owned protected areas.

Our overall intent is to provide much needed information and perspective on this important new conservation trend in terms of both theory and practice. Hopefully, the discussion will also entice other researchers to focus attention on private parks, leading to additional and deeper

economic analyses. Finally, the information

should be useful wherever biodiversity remains threatened, wherever conservationists are looking for new partners, and wherever private reserves are being established, which includes most of the industrialized and developing world.

2. Theoretical framework

Bennett (1995) offers a tripartite theoretical jus-tification for private sector conservation initia-tives. Reasons include ameliorating a government failure (i.e. compensating for government’s appar-ent undersupply of protected areas), reducing free-riding (i.e. not ‘crowding out’ altruistic en-deavors), and encouraging joint supply of public goods (i.e. landowners supplying indirect, non-use values that benefit society at large).

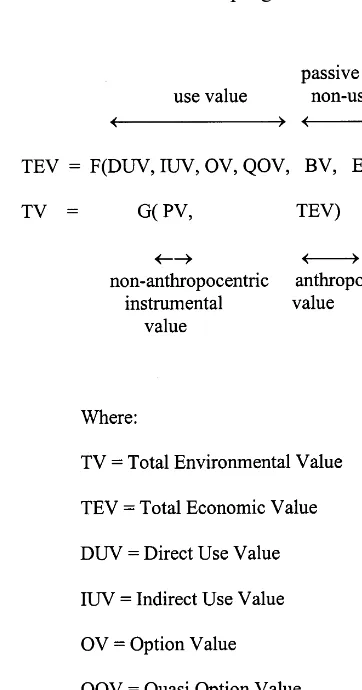

Economists have started paying increased at-tention to the myriad non-market values provided by protected areas in addition to traditional mar-ket values. A formula for calculating the total value of a park appears in Fig. 1. Note that passive or non-use values are an important part of the equation, and that provision of these benefits can come not just from state-owned parks, but from private ones as well. In the equation, be-quest value represents the value of keeping a resource intact for one’s heirs (Krutilla, 1967). Option value refers to the value of the option to make use of the resource in the future (Weisbrod, 1964). Quasi-option value is the value of the future information protected by preserving a re-source (Arrow and Fisher, 1974; Henry, 1974; Fisher and Hanemann, 1983). Existence value em-bodies the value conferred by assuring the sur-vival of a resource (Krutilla, 1967; Pearce and Turner, 1990).

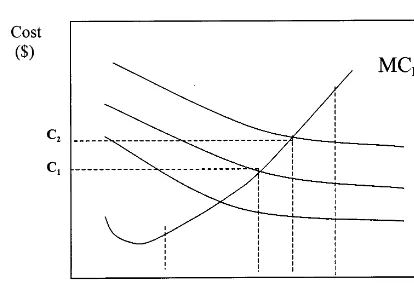

Given this suite of public and private benefits, how might landowners decide how much land to protect? Fig. 2 shows how landowners might allo-cate resources. The figure is derived from two sources in particular (Edwards, 1995; Chapman, 1997), and is based on the assumption that a producer is willing to produce to the point at which the marginal cost of provision of one extra unit is equal to the marginal benefit derived from one extra unit. If landowners take into account

only their own benefits (MBL), rather than the

marginal benefit to society (MBS), they will

pro-tect QL, which falls short of the area society

would want protected (QS). On a theoretical level,

the global proliferation of conservation incentive programs represents society’s attempt to compen-sate landowners for this externality.

Fig. 2. Costs and benefits of protecting natural areas on private lands.

minimum area of QM1, whereas a jaguar might

require a minimum of QM2 (Fig. 2). Even small

private reserves, therefore, may be sufficiently large to maintain viable populations of certain species. What matters most are management objectives and connectivity to other protected ar-eas.

Finally, landowner decisions concerning the amount of land to protect do not occur in a vacuum and can be affected by larger trends. This is especially true for reserves that have an eco-tourism business. For example, ecoeco-tourism re-serves can be in what Yu et al. (1997) described as a classic free rider situation. Given the small amount of land needed to stage a hike in the woods, and the fact that most tourists are inca-pable of recognizing ecological damage in a re-serve, owners do not really need to maintain a large or ecologically intact park. Instead, they can rely on a country’s conservation reputation to bring a steady stream of paying visitors, regard-less of conditions in their own reserves.

3. Methods

Data were collected by the first author during 14 months of fieldwork in Costa Rica, from June 1997 to August 1998. The fieldwork was part of a larger study on private reserves, including their types, ownership patterns, social implications, spatial issues, objectives, and experience with a government incentives program. Costa Rica was selected as the country to study for its reputation as a conservation innovator, for its strong legal support for ownership and protection of private land, and because previous studies have shown it to be a location where private reserves are flour-ishing. For the purposes of this study, private reserves were defined as any land of twenty hectares or more that was not owned by a govern-ment entity, and was managed with the intent of preserving the land in a mostly undeveloped state. When the study began, no comprehensive list of private reserves in Costa Rica existed. We devoted 2 months to developing such a list, drawing to-gether records from a variety of governmental and non-governmental sources.

The size of the externality for the landowner

(MBS minus MBL) is typically greater than that

depicted in Fig. 2. Marginal benefits consist not just of the revenue reserve owners might receive from their natural areas through ecotourism, har-vesting forest products, and other revenue pro-ducing activities, but also from non-market values. Thus, the marginal benefit curve can be subdivided to differentiate market income from

other benefits. The MRL curve in Fig. 2 shows

this relationship, representing the market income

earned by a private nature reserve. The

landowner, then, has the added externality pre-sented by his or her non-monetary benefits of having a nature reserve. The size of this additional

externality (MBL minus MRL) depends on the

value the owner places on non-market benefits, which are typically related to management

objec-tives. For example, MRL for a reserve owner

focused on generating profits would be higher than that of an owner of a non-profit reserve.

The minimum amount of land needed for eco-logical viability also varies. We have shown how a landowner decides how much land to protect, and that this area is smaller than what society would like to see. But like the externality faced by re-serve owners, minimum size requirements also can differ. Management goals affect not just the exter-nality, but also the amount of land needed. The

amount of land protected (QL) may be adequate

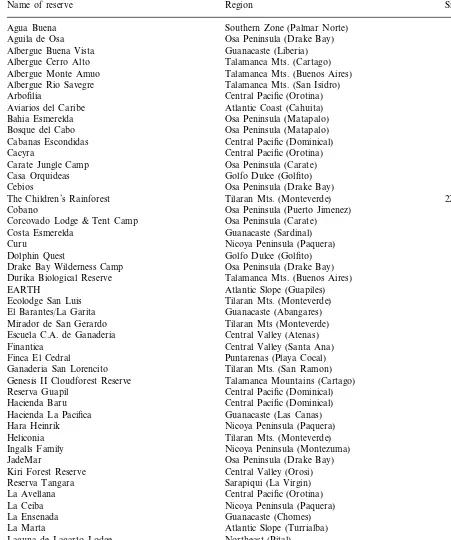

Primary data collection consisted of a struc-tured survey implemented during face-to-face in-terviews with 68 reserve owners. Table 1 lists these reserves, including their locations and sizes. Sup-plemental information reserves’ levels of protec-tion and land uses appear in Langholz (1999a) . The survey included a combination of closed and open-ended questions, thus soliciting not just quantitative data for comparisons across reserves, but also detailed qualitative information for added depth. Conducting the survey face-to-face provided control over who represented each re-serve, overcame illiteracy obstacles, and bypassed an often-unreliable postal system. It also in-creased the response rate by giving the interviewer the opportunity to work around reserve owners’ schedules, and assure them of confidentiality. Seven additional reserves participated in a pilot test. The first author conducted 57 of the inter-views (including the pilot test), and a research assistant did the remaining 18. Forty-six of the reserves were selected at random from a list of 211 suspected reserves. The remaining 22 were inten-tionally added to the sample because they formed part of the study that was exploring participation in a specific incentives program.

Interviews were conducted in Spanish or En-glish, according to the reserve owner’s preference. We tape recorded and transcribed all interviews, except for three cases where the owner requested that we not tape a portion or the entire interview. In addition to the interviews, we examined docu-ments related to the individual reserves, visually inspected the premises of 42 of them, and inter-viewed numerous local residents, government offi-cials, and conservation NGO representatives. These multiple data sources, as well as discussion of preliminary findings with key informants, pro-vided ongoing triangulation of the data (Patton, 1990).

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Rethinking optimality of nature reser6e size

In their landmark book on economics of pro-tected natural areas, Dixon and Sherman (1990)

correctly note that private parks tend to be small. Many large reserves exist, however, such as

80 000-hectare Hato Pinero in Venezuela,

270 000-hectare Pumalin in Chile, and several re-serves of over 100 000 hectares in Brazil. As described in Fig. 2, several factors influence the quantity of hectares a landowner will protect as a private park. These factors form the basis of landowner views on optimality of nature reserve size. For decades, island biogeography theory and concern for megafauna have mandated a ‘bigger is better’ approach to parks (e.g. MacArthur and Wilson, 1967, Diamond, 1975, Simberloff and Abele, 1976). Private parks, however, require an expanded notion of optimal protected area size. The 68 reserves in our study ranged in size from 20 to 22 000 hectares, but had a median of only 101 hectares. We asked landowners to comment on the size of their reserves, hoping to see if their sense of optimality matched the traditional one.

Only 3% (n=2) of reserve owners said their

reserves were ‘too large’. These owners claimed that they would be incapable of managing larger reserves, given available resources. As one owner said, ‘‘It’s too big for me to thoroughly know and

protect.’’ Another 31% of owners (n=21)

de-scribed their reserves as ‘too small’. These owners expressed concern that their reserves were inca-pable of maintaining biodiversity levels over the long-term, especially for large mammals. The

ma-jority (68%, n=44), however, considered their

reserve size to be ‘about right.’ When asked to elaborate, most park owners commented that they wanted to keep reserves at a manageable size. ‘‘If it was bigger, we’re not sure we’d have enough time to care for it,’’ said one owner. Another noted, ‘‘It could be bigger, but then would be too hard for us to control.’’ ‘‘If you’re referring to protection of biodiversity, it’s very small,’’ com-mented a third. ‘‘But if you’re referring to what we can do given our economic resources, it’s very large.

Table 1

Private nature reserve sample group

Name of reserve Region Size (hectares)

252 Southern Zone (Palmar Norte)

Agua Buena

90 Osa Peninsula (Drake Bay)

Aguila de Osa

Guanacaste (Liberia) 500

Albergue Buena Vista

Albergue Cerro Alto Talamanca Mts. (Cartago) 29

147 Albergue Monte Amuo Talamanca Mts. (Buenos Aires)

400 Talamanca Mts. (San Isidro)

Albergue Rio Savegre

Central Pacific (Orotina) 80

Arbofilia

39 Atlantic Coast (Cahuita)

Aviarios del Caribe

20

Bahia Esmerelda Osa Peninsula (Matapalo)

96 Osa Peninsula (Matapalo)

Bosque del Cabo

Cabanas Escondidas Central Pacific (Dominical) 32

41 Osa Peninsula (Drake Bay)

Cebios

Tilaran Mts. (Monteverde) 22 000 The Children’s Rainforest

839

Cobano Osa Peninsula (Puerto Jimenez)

80 Osa Peninsula (Carate)

Corcovado Lodge & Tent Camp

60 Guanacaste (Sardinal)

Costa Esmerelda

84

Curu Nicoya Peninsula (Paquera)

300 Golfo Dulce (Golfito)

Dolphin Quest

Osa Peninsula (Drake Bay) 48

Drake Bay Wilderness Camp

792 Talamanca Mts. (Buenos Aires)

Durika Biological Reserve

600

EARTH Atlantic Slope (Guapiles)

40 Tilaran Mts. (Monteverde)

Ecolodge San Luis

84 Guanacaste (Abangares)

El Barantes/La Garita

35 Mirador de San Gerardo Tilaran Mts (Monteverde)

200 Central Valley (Atenas)

Escuela C.A. de Ganaderia

35 Central Valley (Santa Ana)

Finantica

535 Puntarenas (Playa Cocal)

Finca El Cedral

Tilaran Mts. (San Ramon) 540

Ganaderia San Lorencito

47 Genesis II Cloudforest Reserve Talamanca Mountains (Cartago)

100 Hacienda La Pacifica Guanacaste (Las Canas)

42 Nicoya Peninsula (Paquera)

Hara Heinrik

Tilaran Mts. (Monteverde) 240

Heliconia

130 Nicoya Peninsula (Montezuma)

Ingalls Family

21

JadeMar Osa Peninsula (Drake Bay)

65 Central Valley (Orosi)

Kiri Forest Reserve

Reserva Tangara Sarapiqui (La Virgin) 238

200

Laguna de Lagarto Lodge

17 Las Cusingasa Atlantic Slope (Guapiles)

45 Central Pacific (Uvita)

Los Laureles

Mapache Wilderness Camp Southwest (Palmar Norte) 40

800 Marenco Biological Reserve Osa Peninsula (Drake Bay)

749 Atlantic Coast (Limon)

Pacuare/Mondoquillo

Osa Peninsula (Puerto Jimenez) 249 Platanares

Table 1 (Continued)

Name of reserve Region Size (hectares)

Portalon Central Pacific (Quepos) 420

78 Central Pacific (Dominical)

Punta Achiote

20

Punta Leona Central Pacific (Jaco)

543 Golfo Dulce (Golfito)

Rainbow Adventures Lodge

Rancho la Merced Central Pacific (Uvita) 150

36 Atlantic Slope (Turrialba)

Rancho Naturalista

Osa Peninsula (Golfito)

RHR Bancas 242

Guanacaste (Liberia)

Rincon de la Vieja Lodge 296

95 Talamanca (BriBri)

Samasati

Tilaran Mts. (Monteverde)

Reserva Santa Elena 310

1650 Central Pacific (Silencio)

Tropical America Tree Farms

101 Tiskita Jungle Lodge Golfo Dulce (Pavones)

400 Atlantic Slope (Turrialba)

Vereh-Tayyutic

Vitacura Atlantic Slope (Tortuguero) 68

100 Nicoya Peninsula (Samara)

Werner Sauter

aAlthough this reserve did not meet the 20 hectare minimum size requirement, its owner has founded a local conservation organization that is protecting 1800 additional hectares in the vicinity.

Despite this finding, several factors compound the size issue. For example, landowners no doubt face economies and diseconomies of scale. The number of park guards and other employees needed to protect a 5000-hectare reserve, for ex-ample, may be no greater than what is required to protect 4000 hectares. On the other hand, costs such as fencing, signage, and property taxes will grow in proportion to an expanding reserve.

Similarly, the status of surrounding lands can influence a reserve owner’s size decisions. Neigh-boring lands may be overly developed or too expensive to justify purchase for protection pur-poses. Likewise, adjacent lands might already be operated as protected areas, either by private landowners, or as was the case with roughly half of our study group, by the government (51.5%,

n=35). This close proximity to publicly protected

areas causes a wide variety of biological and financial costs and benefits to private nature re-serve owners, which are detailed in Langholz (1999a,b).

4.2. Market 6alue: profitability among pri6ate

reser6es

In addition to size considerations, the theoreti-cal framework also discussed how market values

vary among private reserve owners (Fig. 2). One of the most important market values of private reserves is their profitability. Previous research has shown that private nature reserves in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa can be a

profitable venture, and that their overall

profitability appears to be rising (Alderman, 1994; Langholz, 1996a,b). One private reserve, in fact, reportedly generated more revenue than all of Costa Rica’s national parks combined (Church et al., 1994). Much of this financial success can be attributed to the ecotourism boom of the last two decades. This study sought to go beyond mere profit and loss data to exploring three other

as-pects of profitability. First, we looked at

(i.e. future profit, and surrounding lands). A com-prehensive assessment of motives behind private reserves appears in Langholz (1999a).

Having profit as a motive is one thing, but actually being profitable is quite another. We also assessed, therefore, the extent to which owners believe reserves to be a profitable land use. Al-though collecting detailed financial information on each reserve was beyond the scope of this study, the data on perceived profitability were quite revealing. When asked if maintaining the natural area was a profitable use of the land,

nearly as many owners disagreed (48.5%, n=33)

as agreed (51.5%, n=35). The two groups were

also split evenly within themselves, among those ‘strongly’ or ‘mildly’ agreeing or disagreeing. The

fact that 11.8% (n=8) reserves were owned by

non-profit organizations, and that 39.7% (n=27)

hosted tourists either ‘rarely’ or ‘never,’ may ex-plain the wide discrepancy. As mentioned above, land stewardship was often a higher priority than making money.

Finally, we explored the extent to which owners depend on reserves for revenue generation. Previ-ous studies (Langholz, 1996a, Alderman, 1994) discussed the numerous ways private reserves cre-ate revenue. Given these options, do reserve own-ers in Costa Rica rely on their reserves for revenue? Results showed overall reliance on re-serves for annual income to be weak at best. Only

40% (n=27) agreed with the statement, ‘‘The

natural area is currently an important source of annual revenue.’’ Owners had strong opinions,

with 29.4% (n=20) strongly agreeing and 48.5%

(n=33) strongly disagreeing. As noted above,

many reserves were not involved in the eco-tourism industry. The number of reserves engaged in other revenue-producing activities was even

lower. For example, only 22.0 (n=15) harvested

medicinal plants from the reserve either

‘some-times’ or ‘often’. Only 16.2% (n=11) mined rocks

or sand from the reserve, and 10.3% (n=7)

uti-lized wild food plants. None harvested wildlife or sold logs. These results suggest market values tell only part of the story at private reserves.

4.3. Non-market factors: the importance of bequest 6alue

As suggested in Fig. 2 and in the preceding section, non-market values play an important role at private reserves. While the various non-market values mentioned in Fig. 1 may be similar across public and private natural areas, bequest value may particularly important at private reserves. Bequest value refers to the value of keeping a resource intact for one’s heirs (Krutilla, 1967; Barbier et al., 1995). With publicly owned parks this value is generalized across society at large. Privately owned parks, however, have a bequest value that is directly attributable to the owners’ heirs rather than to broader society. For example,

75% of owners (n=51) strongly agreed with the

statement, ‘‘Someday in the future, I would like to see a child of mine take over maintaining the

natural area.’’ Another 11.8% (n=8) mildly

Table 2

Economic factors as motivating forces behind private nature reservesa

Mean

Economic Motive Agreeing (%)

I maintain a natural area because it is a financially wise thing to do. 52.9 2.53 2.38 I maintain a natural area because it will be worth a lot of money in the future. 51.5

50.0 2.34

I maintain a natural area because it is a profitable use of the land.

2.24 42.6

I maintain a natural area because it makes the surrounding agricultural lands more productive.

1.91 33.8

I maintain a natural area because I will not have to pay taxes on that portion of my land.

1.93 I maintain a natural area because it provides a regular stream of financial revenue. 30.9

29.4

I maintain a natural area because it pays more money than any other land use, including cattle, 1.88 agriculture, or logging.

agreed with the statement, and only 13.3% (n=9) mildly or strongly disagreed.

We asked a backup question and got similar

results. More than three-fourths (76.5%, n=52)

of owners agreed with the statement, ‘‘I maintain a natural area because it will be a valuable inher-itance for my children.’’ We intentionally left the word ‘valuable’ ambiguous, letting owners define it in their own terms. Some interpreted it in a strictly financial sense, while others viewed it more broadly to include various non-market values.

As a final indicator, we asked an open-ended question on motives behind reserve establishment and operation. Bequest value figured prominently here, as well, with many reserve owners expressing a desire to save the natural area for ‘future gener-ations’. Although several spoke in general terms, other reserve owners were thinking of their own children in particular. ‘‘My kids love the bush, and I hope they stay here when I disappear. I want to leave some kind of legacy for them,’’ said one reserve owner. Another commented, ‘‘It’s for my kids. I’d like to give them a natural environ-ment. They’re young now. And when they’re older there might not be many natural areas left.’’ Assessing all of private reserves’ non-market val-ues was beyond the scope of this study. What is clear, however, is that bequest value is an espe-cially important non-market value for reserve owners.

5. Conclusions

The results point to three main conclusions. First the surge of private parks requires a broad-ened view of optimality regarding reserve size. Bigger is not necessarily better. Despite a median size of only 101 hectares, the vast majority of reserve owners were satisfied with the size of their reserves. Although private reserves are capable of being extremely large, what is most important is matching a reserve’s size to the availability of resources to manage it well. Decisions on reserve size can also be influenced by economies and diseconomies of scale, and by proximity to other protected natural areas.

Second, profitability is an important motivator for many reserves, second only to conservation-re-lated reasons. Results were mixed regarding whether or not the reserves are actually a profitable land use, with nearly as many owners agreeing as disagreeing. Finally, a majority of reserve owners do not even depend on their

re-serves for revenue generation, with 60.3% (n=41)

disagreeing that their natural area is currently an important source of revenue.

Third, while public and private parks are val-ued in many of the same ways, they may differ in at least one important respect. Private park own-ers are likely to place an especially high ‘bequest

value’ on their reserves. Eighty six percent (n=

59) of reserve owners agreed that they would like to see a child of theirs take over managing the

park some day. Additionally, 76.5% (n=52)

agreed that one of the reasons they maintain a natural area is because it will be a valuable inher-itance for their children. This desire to pass on a direct family legacy represents a previously un-documented and extremely important non-market value of private reserves.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a National Science Foundation grant on ‘Ecological and Social Chal-lenges in Conservation’ (BIR-9113293, DBI-9602244), and by the Central America Committee of the Cornell International Institute for Food, Agriculture, and Development. Special thanks go to Marta Marin and Amos Bien at the Red Costarricense de Reservas Naturales, Juan Ro-driguez and Eduardo Madrigal Castro at

MI-NAE/SINAC, numerous colleagues at Cornell

who provided input, Brian Daly, and especially the refuge owners in Costa Rica who were so generous with their time and information.

References

Adams, A. (Ed.), 1962. First World Conference on Parks. National Park Service, Washington DC.

Alderman, C., 1994. The economics and the role of privately owned lands used for nature tourism, education, and con-servation. In: Munasinghe, M., McNeely, J. (Eds.), Pro-tected Area Economics and Policy: Linking Conservation and Sustainable Development. IUCN and The World Bank, Washington DC, pp. 273 – 305.

Alyward, B., Allen, K., Echeverria, J., Tosi, J., 1996. Sustain-able ecotourism in Costa Rica: The Monteverde Cloud-forest Preserve. Biol. Conserv. 5, 315 – 343.

Amend, S., Amend, T., 1992. Human occupation in the na-tional parks of South America: a fundamental problem. Parks 3, 4 – 8.

Arrow, K.J., Fisher, A.C., 1974. Environmental preservation, uncertainty, and irreversibility. Q. J. Econ. 88, 312 – 319. Barbier, E.B., Brown, G., Dalmazzone, S., Folke, C., Gadgil,

M., Hanley, N., Holling, C.S., Lesser, W.H., Ma¨ler, K.G., Mason, P., Panayoutou, T., Perrings, C., Turner, R.K., Wells, M., 1995. The economic value of biodiversity. In: Heywood, V.H., Watson, R.T. (Eds.), Global Biodiversity Assessment. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 823 – 914.

Barborak, J., 1995. Institutional options for managing pro-tected areas. In: McNeely, J. (Ed.), Expanding Partner-ships in Conservation. Island Press, Washington DC, pp. 30 – 38.

Bennett, J., 1995. Private sector initiatives in nature conserva-tion. Rev. Market. Agric. Econ. 63, 426 – 434.

Borrini-Feyerabend, G., 1996. Collaborative Management of Protected Areas: Tailoring the Approach to the Context. World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland. Brandon, K., Redford, K., Sanderson, S. (Eds.), 1998. Parks

in Peril: People, Politics, and Protected Areas. Island Press, Washington DC.

Brandon, K., 1996. Ecotourism and Conservation: A Review of Key Issues. World Bank, Washington DC Global Envi-ronment Division, Biodiversity Series, Paper c033. Chapman, D., 1997. Presentation Given to the Protected Area

Management Group on the Economics of Protected Natu-ral Areas. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY April 28. Church, P., Berwick, N., Martin, R., Mowbray, R., 1994.

Assessment of USAID Biological Diversity Programs: Costa Rica Case Study. USAID Technical Report. United States Agency for International Development, Washington DC.

Diamond, J.M., 1975. Island biogeography and conservation: strategy and limitations. Science 193, 1027 – 1029. Dixon, J.A., Sherman, P.B., 1990. Economics of Protected

Areas: A New Look at Benefits and Costs. Island Press, Washington DC.

Echeverria, J., Hanrahan, M., Solorzano, R., 1995. Valuation of non-priced amenities provided by the biological re-sources within the Monteverde Cloudforest Reserve. Ecol. Econ. 13, 43 – 52.

Edwards, V., 1995. Dealing in Diversity: America’s Market for Nature Conservation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Fisher, A.C., Hanemann, W.M., 1983. Option Value and the Extinction of Species. Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics, University of California, Berkeley, CA Work-ing Paper 269.

Glick, D., Orejuela, J., 1991. La Planada: looking beyond the boundaries. In: West, P., Brechin, S. (Eds.), Resident Peo-ples and National Parks: Social Dilemmas and Strategies in International Conservation. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ, pp. 150 – 159.

Henry, C., 1974. Investment decisions under uncertainty: the irreversibility effect. Am. Econ. Rev. 64, 1006 – 1012. Horwich, R.H., 1990. How to develop a community sanctuary

— an experimental approach to the conservation of pri-vate lands. Oryx 24, 95 – 102.

Kramer, R., Van Schaik, C., Johnson, J. (Eds.), 1997. Last Stand: Protected Areas and the Defense of Tropical Biodi-versity. Oxford University Press, New York.

Krutilla, J.V., 1967. Conservation reconsidered. Am. Econ. Rev. 57, 778 – 786.

Langholz, J., 1996a. Economics, objectives, and success of private nature reserves in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Conserv. Biol. 10, 271 – 280.

Langholz, J., 1996b. Ecotourism impact at independently-owned nature reserves in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Miller, J., Malek-Zadeh, E. (Eds.), The Eco-tourism Equation: Measuring the Impacts, vol. 99. Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies Bulletin Series, New Haven, CT, pp. 60 – 71.

Langholz, J., 1999a. Conservation Cowboys: Privately-owned Parks and the Protection of Tropical Biodiversity. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY unpublished dissertation. Langholz, J., 1999b. Exploring the effects of alternative

MacArthur, R.H., Wilson, E.O., 1967. The Theory of Island Biogeography. Princeton University Press, New York. Machlis, G., Tichnell, D., 1985. The State of the Worlds

Parks: An International Assessment for Resource Manage-ment, Policy, and Research. Westview, Boulder, CO. McNeely, J., Miller, K., Reid, W., Mittermeier, R., Werner,

T., 1990. Conserving the World’s Biodiversity. World Bank, Washington DC.

Merrifield, J., 1996. A market approach to conserving biodi-versity. Ecol. Econ. 16, 217 – 226.

Mesquita, C.A., 1999. Private Nature Reserves and Eco-tourism in Latin America: A Strategy for Environmental Conservation and Socio-economic Development. Centro Agronomico Tropical de Investigacion y Ensenanza, Turri-alba, Costa Rica unpublished masters thesis.

Murray, W., 1995. Lessons from 35 years of private preserve management in the USA: the preserve system of The Nature Conservancy. In: McNeely, J. (Ed.), Expanding Partnerships in Conservation. Island Press, Washington DC, pp. 197 – 205.

Patton, M., 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Meth-ods, 2nd ed. Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Pearce, D.W., Moran, D., 1994. The Economic Value of Biological Diversity. Earthscan, London.

Pearce, D.W., Turner, R.K., 1990. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment. Harvester Wheatsheaf, Hemel Hempstead, UK.

Schelhas, J., Greenberg, R. (Eds.), 1996. Forest Patches in Tropical Landscapes. Island Press, Washington DC. Schmidt, K., 1996. The costs and benefits of privatization: an

incomplete contracts approach. J. Law Econ. Organization 12, 1 – 24.

Shichor, D., 1995. Punishment for Profit. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Simberloff, D.S., Abele, L.G., 1976. Island biogeography the-ory and conservation practice. Science 191, 285 – 286. Uphoff, N., Langholz, J., 1998. Incentives for avoiding the

tragedy of the commons. Environ. Conserv. 25, 251 – 261.

Van Schaik, C., Terborgh, J., Dugelby, B., 1997. The silent crisis: the state of rain forest nature reserves. In: Kramer, R., Van Schaik, C., Johnson, J. (Eds.), Last Stand: Pro-tected Areas and the Defense of Tropical Biodiversity. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 64 – 89. Vickers, J., Yarrow, G., 1988. Privatization: An Economic

Analysis. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Wearing, S., Larsen, L., 1996. Assessing and managing the sociocultural impacts of ecotourism: revisiting the Santa Elena Rainforest Project. The Environmentalist 16, 117 – 133.

Weisbrod, B., 1964. Collective consumption services of indi-vidual consumption goods. Q. J. Econ. 77, 71 – 77. Wells, M., Brandon, K., 1992. People and Parks: Linking

Protected Area Management with Local Communities. In-ternational Bank for Reconstruction, Washington DC. Western, D., Pearl, M. (Eds.), 1989. Conservation for the

Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press, New York. Western, D., Wright, M., Strum, S. (Eds.), 1993. Natural Connections: Perspectives in Community-Based Conserva-tion. Island Press, Washington DC.

Western, D., 1989. Conservation without parks: wildlife in the rural landscape. In: Western, D., Pearl, M. (Eds.), Conser-vation for the Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 158 – 165.

Wilson, E.O., 1989. Conservation: the next hundred years. In: Western, D., Pearl, M. (Eds.), Conservation for the Twenty-first Century. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 3 – 7.

World Resources Institute, The United Nations Environment Programme, The United Nations Development Pro-gramme, and The World Bank, 1998. World Resources 1998 – 99. Oxford University Press, New York.

Yu, D.W., Hendrickson, T., Castillo, A., 1997. Ecotourism and conservation in Amazonian Peru: short-term and long-term challenges. Environ. Conserv. 24, 130 – 138. Zube, E.H., Busch, M.L., 1990. People – park relations: an

international review. Landscape Urban Plan. 19, 115 – 132.