Tadoku jugyo seiko eno kagi

Teks penuh

(2) Kinki University English Journal No.1. Introduction Extensive Reading (ER) has been rapidly gaining popularity in second and foreign language curriculum all over the world due to its effectiveness in improving learners' reading, listening, and writing proficiencies (e.g., Elly & Mangubhai, 1983; Hayashi, 1999; Robb & Susser, 1989; Walker, 1997). In addition, many studies have reported that ER promotes positive affect toward the target language (e.g., Day & Bamford, 1998; Mason & Krashen, 1997; Takase, 2004a). As stated by Smith (1985), ER enables learners to "learn to read by reading," and consequently, the key to success in learning to read through an ER program is to read a vast amount in the target language. However, the notion of amount varies from person to person. Day and Bamford (2002) stated that "a book a week is probably the minimum amount of reading necessary to achieve the benefits of extensive reading and to establish a reading habit" (p. 138). According to Robb (2002), even one book a week would be a burden for busy students. After observing the reading performance of many university students, Sakai (2002) argued that one million words is the turning point in reading proficiency. He claimed that learners will become accustomed to reading extensively and will be able to enjoy reading authentic material after reading one million words. According to Anderson, Wilson and Fielding (1988), the average fifth grade student in the United States reads approximately one million words per year. Therefore, it seems reasonable that after reading one million words, learners of a second or foreign language will become able to read fluently in the target language. To date, however, none of my high school or university students have been able to read one million words in a year. The largest volume of material read by high school and university students I have taught were 550,000 words and 850,000 words, respectively. Suzuki (1996) reported that his high school students started to improve in their achievement tests after reading approximately 200 pages, which at 250-300 words per page can be roughly estimated at 50,000-60,000 words. Takase (2007a) reported that learners who read 50,000-60,000 words started to feel comfortable reading English books without translation. In the case of Japanese high school students that the researcher taught during the last decade, those who read over 50,000 words were able to overcome the feeling of weakness or fear of reading long English passages in standardized achievement tests and university entrance examinations. Those who read over 100,000 words showed an increase in their performance on the reading comprehension sections of achievement tests. Those who read over 300,000 words showed an 120.

(3) The Two Most Critical Tips for a Successful Extensive Reading Program (Takase). even greater increase in their overall achievement test scores. In addition, they established good reading habits. In order for learners to learn to read, it is crucial for them to read a vast amount; however, it has often been argued at conferences, including the Japan Extensive Reading Association (JERA), that there are always some students who are not motivated to read (Takase, 2002, 2004a, 2007c). Thus, the most critical element for ER to be effective is motivating learners to read a great amount of English. Several researchers and practitioners have offered tips for a successful ER program (Day & Bamford, 2002; Robb, 2002; Sakai, 2005). Day and Bamford (2002) proposed ten principles for teaching Extensive Reading: 1. The reading material is easy. 2. A variety of reading material on a wide range of topics must be available. 3. Learners choose what they want to read. 4. Learners read as much as possible. 5. The purpose of reading is usually related to pleasure, information and general understanding. 6. Reading is its own reward. 7. Reading speed is usually faster rather than slower. 8. Reading is individual and silent. 9. Teachers orient and guide their students. 10. The teacher is a role model of a reader. (pp. 137-139). These principles are all essential for any level of ER class. Robb (2002), however, argued that some of these principles would not be applicable to students in Japan and many other Asian countries. According to Robb, the average Japanese university student takes fifteen 90-minute classes per week, in which there is usually no designated reading class where students can read under the guidance of a teacher, as Day and Bamford explained in Principles 8 and 9. In addition, students are occupied with extra curricular activities, such as part-time jobs, sports, clubs, and social life (Robb, 2002, Takase, 2004a). Therefore, many students have difficulty in finding time to read either inside or outside the classroom. Robb argues that under such circumstances, simple encouragement alone will not be effective. Rather, some kind of enforcement, such as a quick follow-up task or a short book report is effective for motivating students to 121.

(4) Kinki University English Journal No. 1. read. He claimed that as long as reading is done with "a large volume of material with less emphasis on comprehension" (p.147), it can be termed "extensive reading," even though it does not conform to the above principles. Sakai (2005) advocated what he calls "Three Golden Rules" to successful ER: 1) use no dictionary, 2) skip the part you do not understand, and 3) stop reading when you find a book difficult. Sakai's first rule which forbids dictionary use is also mentioned by Day and Bamford in their Principle 7, emphasizing that learners should not use a dictionary while they are reading in order to promote reading fluency. Sakai's second rule accords with Day and Bamford's Principle 5. Both Day and Bamford and Sakai emphasize that the goal of extensive reading is not one hundred percent comprehension; therefore, skipping difficult parts is acceptable as long as it does not interfere with readers' understanding or reduce their enjoyment of reading. Sakai's third rule also accords with Day and Bamford's Principle 3. They claim that the free choice of books should be extended to the freedom to stop reading, saying "Correlative to this principle, learners are also free, indeed encouraged, to stop reading anything they find to be too difficult" (p. 137). Takase (2007a) reported that the most critical tips in motivating learners to read are easy ma.t erials and in-class reading under the teachers' guidance. In order for learners to read with enjoyment, books should be easy enough for them to read at a certain speed without using a dictionary. Japanese students, in particular, who have been trained to read English using a constant yakudoku (translation-reading) method (Hino, 1988) in secondary school, need a vast volume of easy material in order to unlearn the word-by-word translation habit. Takase (2004a) found that among several factors that discouraged her high school students from reading, the three most powerful demotivating factors that intimidated learners from reading extensively were a lack of easy material, time-consuming after-reading tasks, and a lack of time for reading due to their busy schedules. She succeeded in increasing her students' reading volume immensely by providing them with very easy books and in-class reading time, as well as by freeing them from the burden of writing after-reading summaries (Takase 2004b, 2005). She had similar results with her university students (Takase, 2007a). Many of her university students from a prestigious university in Osaka favored easy picture books and the easiest graded readers with pictures and illustrations over higher level graded readers which have hardly any pictures or illustrations. She also reported that almost all the students continued reading when they had in-class 122.

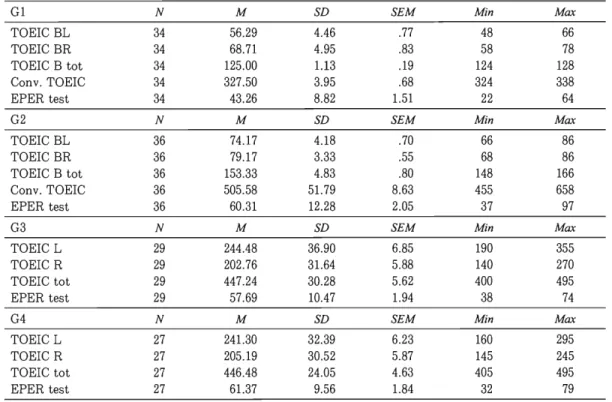

(5) The Two Most Critical Tips for a Successful Extensive Reading Program (Takase). Sustained Silent Reading (SSR) time, whereas approximately 30% of the students stopped reading in the second semester when in-class reading time was not provided due to the tight class schedule. In the present study, different groups of participants from a different university participated in ER under somewhat different circumstances. The researcher made an attempt to find out whether the same results would be achieved. Thus, the researcher posed the following questions: 1. Will easy material at the beginning stage of ER be effective in motivating any level of university students? 2. Will in-class SSR be effective in motivating any level of university students? Method Participants. The participants in this study were 160 Japanese university students from two freshman classes: Group 1 (G 1: n=34), Group 2 (G2: n=36); two sophomore classes: Group 3 (G3: n=29), Group 4 (G4: n=27) and one repeater class for students who failed to pass the class, Group 5 (G5: n=34). Students from Gl to G4 were grouped by English ability, and G5 consisted of students at different levels of English ability. The participants were all non-English majors and the English proficiency levels of the participants from G 1 to G4 were from low intermediate to high intermediate. As shown in Table 1, the mean scores of the total TOEIC Bridge for Gland G2 were 125.00 (SD = 1.13) and 153.33 (SD=4.83), out of a possible 180, which are roughly converted to TOEIC scores of 327.50 (SD=3.95) and 505.58 (SD=51.79), out of a possible 990, respectively. The TOEIC mean scores for G3 and G4 were 447.24 (SD=30.28) and 446.48 (SD =24.05), respectively. The mean scores of the cloze test developed by the Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading (EPER), which was administered during the first session of the semester to participants of Gl, G2, G3, and G4, were 43.26 (SD=8.82), 60.31 (SD = 12.28), 57.69 (SD= 10.47), and 61.37 (SD=9.56) out of a possible 141, respectively. English proficiency levels of G5, which consisted of students from the first to the fourth years, were from low beginning to low intermediate. Their TOEIC scores were not available.. 123.

(6) Kinki University English Journal No.1 Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Participants from G1 to G4 Gl. N. M. SD. SEM. Min. Max. TOEIC BL TOEIC BR TOEIC B tot Conv. TOEIC EPER test. 34 34 34 34 34. 56.29 68.71 125.00 327.50 43.26. 4.46 4.95 1.13 3.95 8.82. .77 .83 .19 .68 1.51. 48 58 124 324 22. 66 78 128 338 64. G2. N. M. SD. SEM. Min. Max. TOEIC BL TOEIC BR TOEIC B tot Conv. TOEIC EPER test. 36 36 36 36 36. 74.17 79.17 153.33 505.58 60.31. 4.18 3.33 4.83 51.79 12.28. .70 .55 .80 8.63 2.05. 66 68 148 455 37. 86 86 166 658 97. G3. N. M. SD. SEM. Min. Max. TOEIC L TOEIC R TOEIC tot EPER test. 29 29 29 29. 244.48 202.76 447.24 57.69. 36.90 31.64 30.28 10.47. 6.85 5.88 5.62 1.94. 190 140 400 38. 355 270 495 74. G4. N. M. SD. SEM. Min. Max. TOEIC L TOEIC R TOEIC tot EPER test. 27 27 27 27. 241.30 205.19 446.48 61.37. 32.39 30.52 24.05 9.56. 6.23 5.87 4.63 1.84. 160 145 405 32. 295 245 495 79. Note. TOEIC BL=TOEIC Bridge Listening, TOEIC BR = TOEIC Bridge Reading. Conv. TOEIC = TOEIC Bridge converted to TOEIC EPER Test=Edinburgh Project on Extensive Reading Test. Descriptive Statistics. Participants from G 1 to G4 were enrolled in the present classes according to their total TOEIC Bridge or TOEIC scores in both the Listening (hereafter L) and Reading (hereafter R) sections. For G 1, G3, and G4 the ranges of scores in Land R were wider than the total TOEIC Bridge or TOEIC scores. As seen in Table 1, the TOEIC Bridge Land R scores for Gl ranged from 48 to 66 (M=56.29; SD=4.46) and from 58 to 78 (M=68.71; SD=4.95), respectively, out of a possible 90 for each section. The TOEIC Land R scores for G3 and G4 ranged from 190 to 355 (M= 244.48; SD =36.90) for G3L, from 140 to 270 (M=202.76; SD=31.64) for G3R, from 160 to 295 (M =241.30; SD=32.39) for G4L, and from 145 to 245 (M=205.19; SD=30.53) for G4R, out. of a possible 495 for each section. Only the G2 results were significantly different, showing smaller ranges in Land R than the total TOEIC Bridge scores. The TOEIC Bridge L, R, and the total scores for G2 ranged from 66 to 86 (M=74.17; SD=4.18), from 68 to 86 (M= 79.17; SD=3.33), from 148 to 166 (M= 153.33; SD=4.83), respectively. One significant difference between the freshmen (G 1, G2) and the sophomores (G3, G4) 124.

(7) The Two Most Critical Tips for a Successful Extensive Reading Program (Takase). was that G1 and G2 had R scores higher than L scores whereas G3 and G4 had L scores higher than R scores.. Procedure. All the participants engaged in ER for 14 weeks in somewhat different ways. Participants in Gland G2 had two gO-minute English classes per week: one in which the set text was to be followed and the other which was left to the discretion of each teacher. ER was practiced for 30-40 minutes as a part of the free day. G3 and G4 met only once a week, therefore, ER was assigned mostly outside of class, except for during the orientation session and about ten minutes for check-out-book time at the end of each class. G5 had two classes per week: one was for video-based listening and the other for ER using a study room in the library where English books were easily accessible. At the beginning of the course, ER was oriented toward the purpose of having all the participants become well aware of the necessity and the effectiveness of reading English books extensively. Participants from G1 and G2 were observed as much as possible and guided by the teacher while they were reading, and G5 had observation and guidance from the teacher during the full gO-minute class all through the semester. In contrast, G3 and G4 were occupied with the prescribed curriculum and had little extra time for ER or individual guidance during the class. Participants were required to read 100 very easy books to begin with in order to unlearn the habitual word-by-word translation which they had acquired in their junior and senior high school English classes. They were instructed to gradually work up to higher levels of graded readers and easy books intended for young native English speakers. They were also required to keep a record of their reading, including date, number of words, time used for reading, reading speed, interest level, and short comments on each book they read. A five-point Likert scale questionnaire was constructed and administered at the end of the first semester in order to investigate the participants' attitudes toward reading.. Reading Materials. Two kinds of reading materials were used: 1) leveled readers and picture books for L1 children published by Harper Collins, Longman, Oxford, Random House,. 125.

(8) Kinki University English Journal No . 1. Scholastic, and other major publishers; and 2) graded readers ranging from 200 to 1300 head words published by Cambridge, Macmillan, Oxford, and Penguin. Initially, the participants were required to use books in the library. However, there were not enough books for all the participants. So in order to supply easy books, approximately 100-200 books were delivered to classes from the researcher's own bookshelf once a week to cover the shortage of material in the library. In this study, all the books were categorized into six groups depending on the type, level, and length. Leveled Readers (LR) 1, LR2, Graded Readers (GR) 1, GR2, GR3, and GR4 were as follows: 1. LRl: Oxford Reading Tree (ORT) (Levels 1-9), ORT Fireflies (ORT-FF). (Stages 1-10), Longman Literacy Land Story Street (LLL-SS) (Steps 1-10), LLL Genre Range (LLL-GR) (1-2), LLL Info Trial (LLL-IT), All Aboard Reading (AAR) (0-2), I Can Read Books (ICR) (0-2), Scholastic Reading (SCR) (1-2), Oxford Classic Tales (OCT) (1-2). 2. LR2: LLL-SS (Steps 11-12), LLL-GR (3-4), AAR (3-4), ICR 3, SCR (3-4), OCT (3-4), ORT True Stories (ORT-TS) (1-2), Wolf Hill (WH) (1-5), Let's Readand-Find-Out (LRFO) (1-2), Mr. Men and Little Miss Series (MMM). 3. GRl: Penguin Young Readers (PYR) (1-2), Foundation Reading Library (FRL) (1-4), Cambridge English Readers Starter (CERO), Macmillan Readers Starter (MMRl), Penguin Readers Easystarts (PGRO), and Oxford Bookworm Starter (OBWO). 4. GR2: PYR (3-4), FRL (5-7), PGRl, CERl, MMR2. 5. GR3: OBW (1-2), MMR (2+), PGR2, Action Readers (AR). 6. GR4: CER3, MMR3, OBW (3-4), PGR (3-4). There is an argument against using children's books with high school or university students. However, when Japanese students, who have been trained to read English using the traditional yakudoku method or word-by-word translation, read English, Japanese translation for each word automatically pops up in their mind. Therefore, in order to unlearn this automatic translation habit and read English and understand the content in English, it is necessary to start by reading a lot of very easy books and, if necessary, with the help of pictures instead of a bilingual dictionary. I. Data Analysis. Prior to analysis, all the data were screened and the participants with any 126.

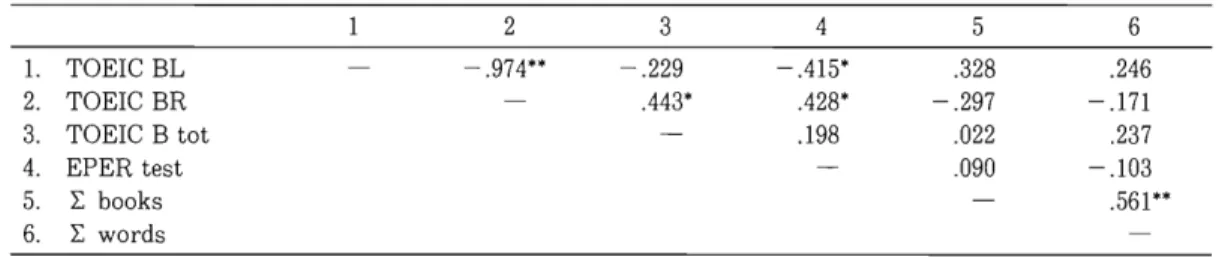

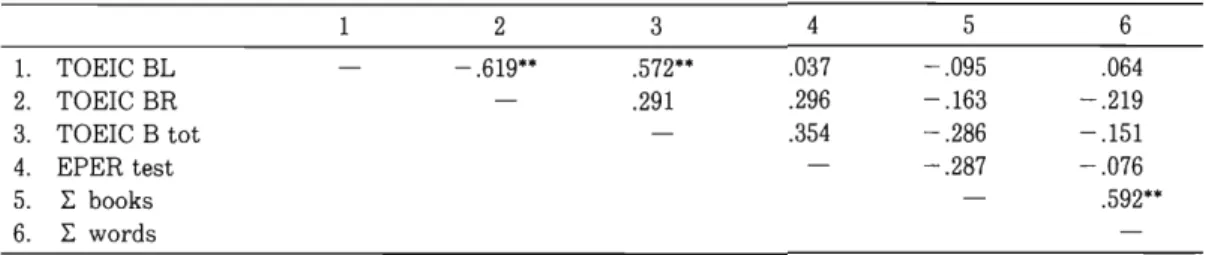

(9) The Two Most Critical Tips for a Successful Extensive Reading Program (Takase). missing values were eliminated. Then, the means and the standard deviations for all the variables were examined for skewness and kurtosis using z-scores. All the variables were normally distributed. Also, the data were examined for univariate outliers using SPSS regression. No outlier was identified. First of all, correlations were calculated in order to examine the relationships between the listening and reading sections of the participants' TOEIC scores, the EPER doze test, and participants' reading amount for the G 1, G2, G3, and G4. Second, the reading volume of participants in all groups was calculated in terms of the number of books and the number of words they read. Third, questionnaire response scores were calculated for each group. Then, in order to investigate the levels and the types of books participants read, all the books they read were sorted and calculated based on the level and type (LRl, LR2, GRl, GR2, GR3, and GR4) for each group.. Results Correlation. First, to determine the relationships among variables, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were calculated for L, R, and the total scores of TOEIC, EPER Test scores, and the amount of reading (the number of books and the number of words) for each group (Tables 2-5). Table 2.. Gl: Relationships Between TOE/C, EPER, and Reading Data (N=34). 2 TOEIC BL 2. TOEIC BR 3. TOEIC B tot 4. EPER test 5. l: books 6. l: words 1.. Table 3.. - .974**. 3 - .229 .443*. 5 .328 -.297 .022 .090. 6 .246 - .171 .237 - .103 .561 **. G2: Relationships Between TOE/C, EPER, and Reading Data (N=36). 2 1. TOEIC BL 2. TOEIC BR 3. TOEIC B tot 4. EPER test 5. l: books 6. l: words. 4 - .415* .428* .198. - .187. 127. 3. 4. 5. 6. .736** .527**. .243 .520** .568**. .205 .323 .400* .139. .065 .238 .221 .071 .658**.

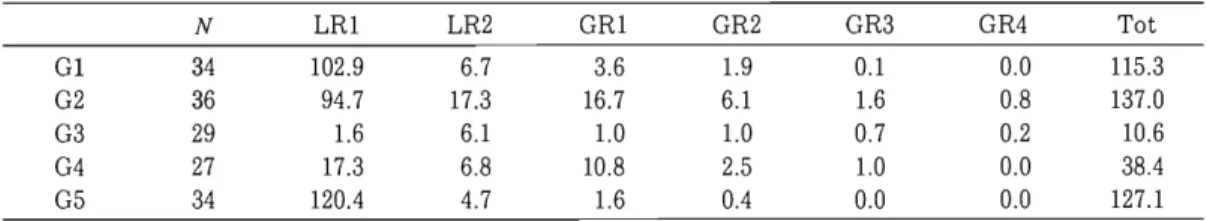

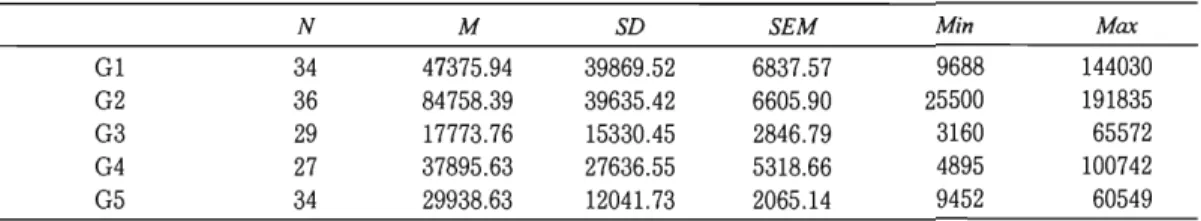

(10) Kinki University English Journal No.1 Table 4.. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6.. TOEIC BL TOEIC BR TOEIC B tot EPER test L books L words Table 5.. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6.. G3: Relationships Between TOE/C, EPER, and Reading Data (N= 29). 2. 3. 4. - .619**. .572** .291. .037 .296 .354. 5 -.095 -.163 - .286 - .287. 6 .064 - .219 -.151 - .076 .592**. G4: Relationships Between TOE/C, EPER, and Reading Data (N= 27). TOEIC BL TOEIC BR TOEIC B tot EPER test L books L words. 2. 3. - .709**. .447 .314. 4 .358 - .008 .472*. 5 .306 -.086 .303 .129. 6 .235 - .070 .227 .118 .901**. Note. **p < .01 level. *p < .05 level. As seen in Tables 2-5, the TOEIC Bridge Land R of Gland G2, and the TOEIC Land R of G3 and G4 were negatively correlated, and they were statistically significant at the p=.Ol in G1, G3 and G4. Regarding the EPER Test, it was significantly correlated with TOEIC BR of G1 at the p= .05 level and with TOEIC BR of G2 at the p=.Ol level. The amount of reading that participants did (L Books and L Words). negatively correlated with TOEIC BR of G 1, TOEIC R of G3 and G4, and positively correlated with TOEIC BR of G2, although none of them was statistically significant.. Reading Amount. Based on the participants' self-report and the researcher's observation the amount of reading (L Books and L Words) were computed, then the data were sorted according to the levels of books. Table 6 shows the number of books participants of five groups read, and Table 7 shows the number of words they read. Table 6. Reading Amount o/Gi, G2, G3, G4, and G5 (Lbooks). G1 G2 G3 G4 G5. N. M. SD. SEM. Min. Max. 34 36 29 27 34. 118.94 137.06 10.79 41.26 127.24. 61.69 64.28 6.11 34.94 37.87. 10.58 10.71 1.14 6.72 6.49. 27 60 3 3 41. 272 334 28 122 227. 128.

(11) The Two Most Critical Tips for a Successful Extensive Reading Program (Takase) Table 7. Reading Amount ofGI, G2, G3, G4, and G5 {Lwords-}. G1 G2 G3 G4 G5. N. M. SD. SEM. Min. Max. 34 36 29 27 34. 47375.94 84758.39 17773.76 37895.63 29938.63. 39869.52 39635.42 15330.45 27636.55 12041.73. 6837.57 6605.90 2846.79 5318.66 2065.14. 9688 25500 3160 4895 9452. 144030 191835 65572 100742 60549. As illustrated in Table 6, the average numbers of books G 1 and G2 read were. 118.94 (SD=61.69) and 137.06 (SD=64.28), respectively, and those of G3 and G4 were 10.79 (SD=6.11) and 41.26 (SD=34.94), respectively. Tables 6 and 7 show that the mean number of books participants from G5 read was 127.24 (SD=37.87), which was the second highest; however, the mean number of words was 29,938.63, which was the second lowest. This is explained by the fact that participants from G5 read many easy books compared to other groups.. Questionnaire. For the purpose of this paper, five items of the five-point Likert scale questionnaire are discussed, regarding the reactions and attitudes of participants toward extensive reading. The participants' responses are: 5=strongly agree, 4=agree, 3=cannot decide, 2=disagree, and 1 = strongly disagree. Table 8. Item I : I Read a Lot of Books. G1 G2 G3 G4 G5. N. 5. 4. 3. 2. 34 36 29 27 34. 8.6% 20.0% 0.0% 20.7% 27.3%. 31.4% 28.6% 24.1% 24.1% 42.4%. 37.1% 37.1% 34.5% 13.8% 39.3%. 17.1% 14.3% 27.6% 31.0% 0.0%. 5.7% 0.0% 13.8% 10.4% 0.0%. As seen in Table 8, G3 showed only a 24.1% combined positive response, whereas 40.0% from G 1, 48.6% from G2, 44.8% from G4, and 69.7% from G5 responded positively.. 129.

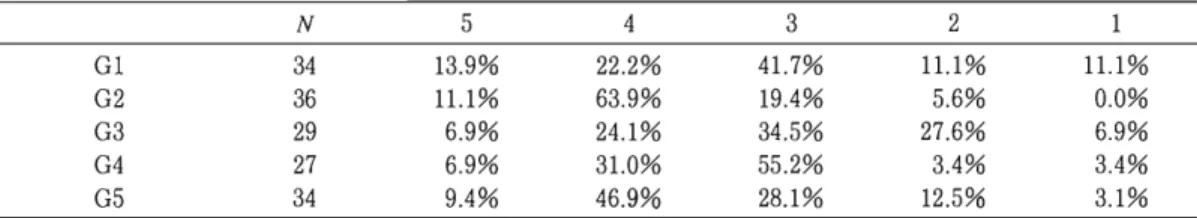

(12) Kinki University English Journal No.1 Table 9. Item 2: I Enjoyed Reading English Books. G1 G2 G3 G4 G5. N. 5. 4. 3. 2. 1. 34 36 29 27 34. 13.9% 22.2% 0.0% 0.0% 36.4%. 27.8% 36.1% 17.2% 37.9% 33.3%. 41.7% 38.9% 48.3% 41.4% 21.2%. 13.9% 2.8% 24.1% 13.8% 6.1%. 2.8% 0.0% 10.3% 6.9% 3.0%. Table 9 illustrates that G3 again showed the smallest percentage of participants (17.2%) who enjoyed reading books, whereas 41.7% from G1, 58.3% from G2, 37.9% from G4, and 69.7% from G5 responded that they enjoyed reading. In contrast, 34.4% from G3 responded that they did not enjoy reading. Table 10. Item 5: I Checked Unknown Words in the Dictionary While Reading a Book. G1 G2 G3 G4 G5. N. 5. 4. 3. 2. 34 36 29 27 34. 0.0% 0.0% 13.8% 13.8% 6.7%. 8.6% 11.1% 17.2% 34.5% 6.7%. 22.9% 19.4% 24.1% 17.2% 20.2%. 28.6% 36.1% 27.6% 13.8% 16.7%. 40.0% 33.3% 17.2% 20.7% 50.0%. As seen in Table 10, all groups, except for G4, showed smaller negative responses than combined positive responses . This means that in G 1, G2 and G5, a smaller number of students consulted a dictionary while they were reading English books, whereas nearly 50% of participants from G4 and 31% from G3 consulted a dictionary. Table II. Item 10: I Became Accustomed to Reading a Whole Book. G1 G2 G3 G4 G5. N. 5. 4. 3. 2. 34 36 29 27 34. 13.9% 11.1% 6.9% 6.9% 9.4%. 22.2% 63.9% 24.1% 31.0% 46.9%. 41.7% 19.4% 34.5% 55.2% 28.1%. 11.1% 5.6% 27.6% 3.4% 12.5%. 11.1% 0.0% 6.9% 3.4% 3.1%. Table 11 illustrates that all groups except for G3 showed a greater percentage of participants' positive responses than negative responses. Participants from G2 and G5 in particular, 75.0% and 56.3% respectively, responded that they became accustomed to reading a whole book.. 130.

(13) The Two Most Critical Tips for a Successful Extensive Reading Program (Takase) Table 12. Item 12: I Want to Continue Reading English Books. G1 G2 G3 G4 G5. N. 5. 4. 3. 2. 34 36 29 27 34. 22.2% 19.4% 0.0% 13.8% 12.1%. 33.3% 44.4% 20.7% 48.3% 24.2%. 27.8% 30.6% 51.7% 20.7% 36.4%. 11.1% 5.6% 10.3% 17.2% 18.2%. 5.6% 0.0% 17.2% 0.0% 9.1%. As seen in Table 12, more participants from all the groups, excluding G3, responded positively. G1, G2, and G4 in particular, 55.5%, 63.8%, and 62.1% respectively, responded that they want to continue reading English books.. Levels and Types of Books Read. All the books that participants read were added up and sorted according to the types (LR or GR) and levels of difficulty for each group. Table 13.. G1 G2 G3 G4 G5. Mean Number of Books Participants Read in Different Levels (per Person). N. LR1. LR2. GR1. GR2. GR3. GR4. 34 36 29 27 34. 102.9 94.7 1.6 17.3 120.4. 6.7 17.3 6.1 6.8 4.7. 3.6 16.7 1.0 10.8 1.6. 1.9 6.1 1.0 2.5 0.4. 0.1 1.6 0.7 1.0 0.0. 0.0 0.8 0.2 0.0 0.0. Tot 115.3 137.0 10.6 38.4 127.1. Note. See Reading Material section for information about LRl, LR2. GRl, GR2. GR3. and GR4 more in de-. tail.. As seen in Table 13, each participant from G 1, G2, and G5 read a total of 106.5, 111.4, 122.0 very easy books (LR1 +GR1) on average, respectively. G3 and G4, on the other hand, read only a small number of books (2.6 and 28.1) from these categories. Discussion The first research question concerned the effectiveness of easy materials for increasing learner motivation and creating a successful ER program. As Table 13 shows, Gl, G2, and G5 read an average of over 100 easy books (LRI +GR1) at the beginning stage of this course, although the participants in G5 mostly continued to read easy books throughout the course. By reading a vast amount of easy books at the beginning stage of ER program (Table 13) without using a dictionary (Table 10), they felt a sense of joy for reading English books (Table 9) and realized that they became accustomed to reading an entire book (Table 11). Moreover, they felt content that they had 131.

(14) Kinki University English Journal No. 1. read over 100 books (Table 8) , and they wanted to continue reading (Table 12). In contrast, Table 13 shows that G3 chose more difficult books from LR2 than easier books from LR1. They read only 2.6 of the easiest books (LR1 +GR1) and then stepped up to higher levels. Participants from G4 read 28.1 of the easiest books (LR1 +GR1), which exceeded 9.3 books from the second level (LR2+GR2). However, reading only 28.1 easy books in fourteen weeks can never be satisfactory to become a fluent reader. As many as 41.4% from both G3 and G4 responded that they did not read a lot books, and they were not satisfied with their own reading amount. In addition, 31% from G3 and 48.3% from G4 consulted a dictionary while reading (Table 10). Therefore, over one-third (34.4%) of G3 and over one-fourth (20.7%) of G4 did not feel a sense of joy in reading English books (Table 9). It is interesting to see, however, that only 20.7% of the participants from G3, and as many as 62.1% from G4 responded that they wanted to continue reading (Table 12). Further research is needed to discover the cause of this difference. One reason participants may have chosen difficult books beyond their reading level is because the idea that "No pain, no gain" is a commonly held belief among both teachers and students in Japanese education (Apple, 2007). Another possibility was pride on the part of many participants from G3 and G4 that discouraged them from choosing very easy children's books, even though they could not read them without consulting a dictionary. Due to the habit of reading English using word-by-word translation with a help of a dictionary, most Japanese learners feel uneasy not using a dictionary or translating as they read (Takase, 2004a). For them, reading is interpreted as translating. They feel that without translation, even a simple sentence cannot be fully comprehended. The second question concerned the effectiveness of SSR. From the results of the book reading records (see Tables 6 and 7) and the questionnaire responses, it is clear that providing students with in-class reading time encouraged them to read a great amount. All the participants from G2 and most participants from G 1 read outside of classroom as well as inside the classroom. There are several reasons that can explain this. First of all, as they were newcomers to the university, they were eager to try to fulfill the course requirements. The second possibility was that after passing the university entrance examination, for which they had studied over one year using texts on difficult topics written in difficult English, participants from Gland G2 felt relaxed and enjoyed reading easy picture books for fun , which, for them, was a completely neW. 132.

(15) The Two Most Critical Tips for a Successful Extensive Reading Program (Takase). approach to reading English. Another reason might be that participants from G 1 and G2 were better readers from the beginning. G 1 and G2 showed larger mean scores on the reading test than on the listening test of the TOEIC Bridge (see Table 1), and"their reading scores significantly correlated with the EPER scores (see Table 2), which measures overall English skills. In contrast, participants from G3 and G4 were better listeners than readers, and had lower mean scores for reading than for listening (Table 1). Above all, in-class reading enabled participants to exchange books and information on the spot as well as to be guided by the teacher while reading. Most important of all, they were simply able to have time to read in class every week. Although all the groups had the same orientation at the beginning of the semester, G3 and G4 lacked observation and guidance afterwards and were not provided with hardly any in-class reading time. Without constant observation and guidance of their reading as well as in-class reading time, we cannot expect a successful ER program (Day & Bamford, 2002). G5 was the only group that the full 90-minute session was used for ER under the guidance of the teacher. It can be assumed that most participants did not like English because they were very poor at it. Whatever their reasons of failing the course one or more times were, they had to repeat the same course reluctantly. Most of the participants showed their dislike or rather strong hatred for English because they could not read or understand a word of the textbooks they had used for the past several years. For some students this feeling started during their junior high school years. When they were shown very easy picture books in this class, their eyes glowed and they started reading them at once. It was the very first time that they had seen picture books in English. Because they were able to understand stories written in easy English using large letters with pictures and illustrations, they read a lot of books (Table 8) without consulting a dictionary (Table 10). They continued reading them until the end of the course, feeling a great sense of joy in reading English books extensively (Table 9). They felt accustomed to reading an entire book in English (Table 11). As a result, more participants responded positively (36.3%) than negatively (27.3%) about continuing reading English books (Table 12).. Conclusion In conclusion, from the results of this study, the two most crucial factors in a successful ER program for learners at any proficiency level are reading an abundance 133.

(16) Kinki University English Journal No. 1. of very easy books at the beginning of ER and having some in-class SSR time where a teacher can observe and guide the learners. These two things were effective in motivating the participants to read extensively in the group of reluctant repeaters with low reading proficiency as well as in the high reading proficiency group. Both groups read a great amount of easy books and enjoyed reading English, showing a hint that a reading habit was developing. On the other hand, two groups where enough in-class reading time was not provided tended to choose more difficult books from the beginning and read with a help of a dictionary. As a result, most participants from these groups did not enjoy reading. They might have reacted differently with in-class SSR under the guidance of an instructor. References Anderson, R., Wilson, P., & Fielding, L. (1988). Growth in reading and how children spend their time outside of school. Reading Research Quarterly 23, 285-303. Apple, M. (2007) . Beginning extensive reading: A qualitative evaluation of EFL learner perceptions. JACET Kansai Journal, 9, 1-14. Day, R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Day, R., & Bamford, J. (2002). Top ten principles for teaching extensive reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14(2), 135-141.. Elley, W. B. , & Mangbhai, F. (1981). The impact of a bookflood in Fiji primary schools. New Zealand Council for Educational Research and Institute of Education: University of South Pacific. Hayashi, K. (1999). Reading strategies and extensive reading in EFL classes. RELC Journal, 30(2), 114-132.. Hino, N. (1988). "Yakudoku": Japan's dominant tradition in foreign language learning. JALT Journal, 10, 45-53. Robb, T. (2002). Extensive reading in an Asian context-An alternative view. Reading in a Foreign language, 14(2), 146-147.. Robb , T., & Susser, B. (1989). Extensive reading vs. skills building in an EFL context. Reading in a Foreign Language, 5(2), 239-251.. Mason, B., & Krashen, S. (1997). Extensive reading in English as a foreign language. System, 25(1), 99-102.. Sakai, K. (2002). Kaidoku Hyakumango [Toward One Million Words and Beyond]. 134.

(17) The Two Most Critical Tips for a Successful Extensive Reading Program (Takase). Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo. Sakai, K. (2005). Kyoshitsu de yomu 100 mango [Reading a million words in the classroom]' Tokyo: Taishukan. Smith, F. (1985). Reading without nonsense (2 nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press. Suzuki, J. (1996). Dokusho no tanoshisa wo keiken saseru tamemo reading shido [Teaching reading for enjoyment]. in Watanabe, T. (ed.), Atarashii yomi no shido [New approach to teaching reading]. 116-123. Tokyo: Sanseido.. Takase, A. (2002). Motivation to read English extensively. Forum for Foreign Language Education, 1. 1-17. Institute of Foreign Language Education and Research, Kansai. University. Takase, A. (2004a). Investigating students' reading motivation through interviews. Forum for Foreign Language Education, 3. 23-38. Institute of Foreign Language. Education and Research, Kansai University. Takase, A. (2004b). Effects of eliminating some demotivating factors In reading English extensively. JALT 2003 Conference Proceedings. Takase, A. (2005). Aru shiritsu koko deno tadoku jyugyo heno chou sen [Extensive reading program at high school level ]. In K. Sakai & M. Kanda (Eds.), Kyoshitsu de yomu 100 mango [Reading a million words in the classroom]' 82-89. Tokyo: Taishukan.. Takase, A. (2007a). Daigakusei no koukateki tadoku shidouhou [The Effectiveness of Picture Books and SSR in Extensive Reading Classes]. Forum for Foreign Language Education, 6. 1-13. Institute of Foreign Language Education and Research, Kansai. University. Takase, A. (2007c). Extensive reading in the Japanese high school setting. The Language Teacher, 31(5), 7-10.. Walker, C. (1997). A self-access extensive reading project using graded readers. Reading in a Foreign Language, 11(1), 121-149.. Appendix ~~~~11U::~9~7/T- ". 1. f£'J:~~~+?t'::fi"'? t:.o 2.. ~~'J:~. 3.. ~~JfjT.:f-A" 0)1*J?i:HJ:J!~~51. 4.. ~~'J:*~t.:' "'?. 5.. ~~~9~C~, ffl~tJt).~'J:~.C'~«t:. o. G7'J)"'? t:. o. < ~0)7'J$.~7'J)"'? t:.o. t:.o. 135.

(18) Kinki University English Journal No. 1 ~~~~cL~~llir~~. < tJ.. "t ~ t:o. 6.. ~~~T ~. ct oj ,: tJ:'? "t ~. 7.. ~~~T ~. ct oj ,: tJ.. "?. "t ~ ~~~~cL~': C ,:gtfLir~tJ.. <tJ.. 8.. ~~~T ~. ct oj ,: tJ.. "?. "t ~ ~~~~cL~ ': C iO)~ G <tJ.. "?. 9. ~~~T ~ ct oj ,: tJ.. "?. "t ~ ~~O)!ti~~ t:. t:o 11. ~~'iftBO)~~O)5fl1%H:~JL"? t:o 12. .: tL iOH? b ~ ~ ~ ~ '1 t: ~ '1 0. ~~"C'O)~~"C'~~jJiO)J:iO)"?. 14. T.:f- A 15.. ~. t: C ~ t. ~. Jaji.O) ~ 'I 01v tJ. *~~Iv"C' t& t: ~ 'I C iW, oj 0. ~~0)*~~1v "C'~~jJ~"'":) '1 t: ~ 'I. C i~'"? "t ~ 'I ~ 0. 16. *~~cL~': C 'i.~ 'It~"? t:o 17. B *~"C'*~~cL~ O)iO)~~ t~o. 136. "?. "t ~. "t ~ t:o. < ~ Ivji;t t:o. 10. ~~O)* 1 iHt~cL~': C ':1ItL "t ~. 13.. "?. t:o.

(19)

Gambar

Dokumen terkait

UndangUndang Nomor 7 Tahun 2004 tentang Sumber Daya Air (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun

Pada tahap formal ini, guru dikirimkan oleh sekolah untuk mengikuti pengembangan keprofesian berkelanjutan di lembaga pelatihan (misalnya P4TK, PT/LPTK, dan

menggambar dengan perangkat lunak berdasarkan tuntutan dunia kerja. Objek penelitian dilakukan di kelas XII TGB SMKN

Cara Meningkatkan Produksi Tanaman Padi Dengan Sistem Tanam Jajar Legowo.. Gerbang Pertanian

Penulis tertarik untuk meneliti dengan menggunakan pengaruh aliran kas bebas dan keputusan pendanaan terhadap nilai pemegang saham dengan set kesempatan investasi dan dividen

Upaya hukum jika suami tidak memberikan nafkah kepada istri dan anak pasca perceraian bagi warga negara Indonesia yang non muslim ialah melakukan permohonan eksekusi ke

Menyusun daftar pertanyaan atas hal-hal yang belum dapat dipahami dari kegiatan mengmati dan membaca yang akan diajukan kepada guru berkaitan dengan materi Identitas dalam

[r]