Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:49

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

What Is the Influence of a Compulsory Attendance

Policy on Absenteeism and Performance?

Jason L. Snyder, Joo Eng Lee-Partridge, A. Tomasz Jarmoszko, Olga Petkova &

Marianne J. D’Onofrio

To cite this article: Jason L. Snyder, Joo Eng Lee-Partridge, A. Tomasz Jarmoszko, Olga Petkova & Marianne J. D’Onofrio (2014) What Is the Influence of a Compulsory Attendance Policy on Absenteeism and Performance?, Journal of Education for Business, 89:8, 433-440, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.933155

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2014.933155

Published online: 04 Nov 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 258

View related articles

What Is the Influence of a Compulsory Attendance

Policy on Absenteeism and Performance?

Jason L. Snyder, Joo Eng Lee-Partridge,

A. Tomasz Jarmoszko, Olga Petkova, and Marianne J. D’Onofrio

Central Connecticut State University, New Britain, Connecticut, USA

The authors utilized a quasiexperimental design across sections of managerial communication and management information systems classes (ND212) to test the impact of compulsory attendance policies on student absenteeism and performance. Students in the compulsory attendance policy condition received an attendance policy that punished excessive absenteeism. Students in the other condition received a policy that told students they were expected to attend but offered neither reward nor punishment. Results suggest that the compulsory policy reduced absenteeism. The policy’s effect on performance depended on the student’s level of prior academic achievement. The authors discuss the findings.

Keywords: absenteeism, attendance policy, compulsory attendance, grades, performance

Instructors and researchers have spent much effort on enhancing student class attendance. They have been driven by the common belief that class attendance leads to better academic performance. Researchers have conducted a num-ber of studies, looking at the relationship between class attendance and performance, and the results suggest that students who attend class are likely to perform better than their peers who miss class frequently.

For example, Schmidt (1983) measured the impact of different time commitments by students to various course activities on the students’ performance in economics clas-ses. The study found that class attendance was the most important factor for student success. Another study of eco-nomics students done by Park and Kerr (1990) demon-strated that the role of class attendance is statistically significant in explaining student grades. A randomized experiment in economics classes, designed by Chen and Lin (2008), aimed to estimate the average attendance effect on student exam performance. They concluded that class attendance had a positive and significant impact on college students’ exam performance. Devadoss and Foltz (1996) found that agricultural economics students who attended all classes performed better than their peers who missed

classes. The difference in grade represented three incre-ments in grade such as CCto BC(Devadoss, 1996).

Although many of the studies linking class attendance to performance have been conducted in economics classes, the results appear to hold for students in other academic dis-ciplines. For instance, Longhurst (1999) affirmed that edu-cation students’ absenteeism results in inadequate learning, disruption in class and compromised performance. Thomas and Higbee (2000) found a strong correlation between class attendance and improved grades in introductory mathemat-ics courses. Silvestri (2003) found grades and attendance to be positively related for a sample of teacher-education stu-dents. Thatcher, Fridjhon, and Cookcroft (2007) reported that “always attending class” was the best predictor of per-formance for cognitive psychology students. Clark, Gill, Walker, and Whittle (2011) reported a moderately positive correlation between attendance and performance for stu-dents from across different geography courses and levels. A study by Snyder, Forbus, and Cistulli (2012) revealed a pos-itive relationship between class attendance and grade for a sample of managerial communication students, with the average A student missing fewer than one class and the average F student missing seven classes during the semes-ter. Lyubartseva and Mallik (2012) presented a study that utilized a sample across educational institutions and differ-ent introductory science courses. They confirmed the strong correlation between attendance and student performance. Indeed, according to the results of a recent meta-analysis,

Correspondence should be addressed to Jason L. Snyder, Central Connecticut State University, Department of Management Information Systems, 1615 Stanley Street, RVAC 210, New Britain, CT 06050, USA. E-mail: snyderjal@ccsu.edu

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.933155

class attendance is the single best predictor of academic performance for college students (Crede, 2010).

Although the preponderance of the evidence confirms the positive relationship between attendance and perfor-mance, there are some researchers who have called the nature of that relationship into question. Chan, Shum, and Wright (1997) examined the perceived link between atten-dance and student performance using two empirical models and found that while one of the models demonstrated a pos-itive relationship between attendance and student perfor-mance, the second model showed only a weak relationship. Hunter and Tetley (1999) argued that attendance does not affect exam performance and noted that pass rates at the universities have increased over the years as attendance rates have fallen. A study conducted by Rodgers (2002) in an introductory statistics course revealed no relationship between attendance and academic performance, even when implementing an incentive scheme.

In the present study we aimed to add to this literature on class absenteeism and class performance. Of particular interest to us is the influence of a compulsory class atten-dance policy on absenteeism and performance. The rela-tionship between absenteeism and performance appears to be robust across a variety of settings, and so it begs the question: Does requiring class attendance influence absen-teeism and performance? In other words, what is the influ-ence of a compulsory class attendance policy on class absenteeism and class performance?

To answer this question, we designed a quasiexperiment utilizing two class attendance policies (see Table 1). The first policy included a simple statement telling the student that attendance was expected. The second policy—the com-pulsory policy—told students that there would be grade-related punishments if the student missed more than three classes during the semester. Students in sophomore-level management information systems (MIS) and managerial communication (MC) classes were provided with one of these two versions of the policy.

SHOULD INSTRUCTORS USE A COMPULSORY ATTENDANCE POLICY?

Given the nature of the relationship between class atten-dance and student performance, should instructors require students to attend class? St. Clair (1999) conducted a

thorough review of the literature and concluded that class attendance policies requiring students to attend should be avoided because their influence on the relationship between attendance and performance was not conclusive. She argued that requiring class attendance may even have a boomerang effect, causing some students to choose to not only be absent from class but to drop out of college. She believed that students may respond strongly to this restric-tion on their ability to make their own choices, a response similar to the phenomenon of psychological reactance. Moreover, Chan et al. (1997), while agreeing that atten-dance improves performance, noted that implementing a grading scheme that mandates student attendance doesn’t significantly improve performance.

In support of the argument that compulsory attendance policies may be harmful, Moore (2005) conducted a study in which he provided developmental education students with a policy containing either (a) penalties for excessive absenteeism or (b) an emphasis on the academic benefits of class attendance in a large introductory biology course. He found that a penalty for excessive absences did not affect attendance or grades, while students in sections of the course in which the importance of attendance was stressed throughout the semester came to class more often and had higher grades.

By contrast, some researchers have argued that compul-sory attendance policies actually lead to fewer absences and better performance. For example, Marburger (2006) concluded that a compulsory attendance policy reduced absenteeism and improved exam performance. In another study, Moore and Jensen (2008) found that a compulsory policy, with a penalty of 7% for missing a biology lab, had a positive effect on the lab grade and on the course grade. In a large economics class, Dobkin, Gil, and Marion (2007) found that a compulsory attendance policy yielded a large, marginally significant discontinuity in student final exam performance.

So what do we know? The literature suggests that the relationship between class attendance and performance is relatively robust. The research exploring the relationship between attendance and performance when attendance is compulsory, however, is not conclusive. However, there exist few studies in the extant literature that look specifi-cally at the relationship between class attendance and per-formance when attendance is compulsory. Therefore, more research into this relationship is warranted.

TABLE 1

Attendance Policies Used in the Present Study

Condition Policy

Simple statement Just as in business, you are expected to be present and on time every day.

Compulsory Research clearly demonstrates that class attendance is important to your success as a student. You may miss up to three classes without

penalty. If you missmore than three classes,each absence will result in apenaltyof one-third of a letter grade (e.g., A to A–). The

maximum penalty you can earn is two letter grades (e.g., A to C).

434 J. L. SNYDER ET AL.

ARE THE EFFECTS OF COMPULSORY ATTENDANCE POLICIES UNIFORM?

Students are not all the same. Some students are higher achievers in the classroom while other students do less well. Although this study is concerned with the relationships among class attendance policy, absenteeism, and class perfor-mance, we also want to know if these relationships hold for students with different levels of academic achievement.

Wyatt (1992) found that grade point average (GPA) was one of the best predictors of absenteeism among first-year col-lege students, and the effect was greatest when the student dis-liked the class. He argued that students with higher GPA are motivated to attend class because they understand the relation-ship between attendance and performance and how much they are likely to lose if they miss class. Dollinger, Matyja, and Huber (2008) found that attendance enhanced exam perfor-mance of high-ability and high-GPA students, relative to their low-ability and low-GPA peers. However, a similar study, conducted in an undergraduate operations management course, yielded totally different results. According to Billing-ton (2008), there was a significant correlation between the number of absences and course grade for students with low GPA, and no correlation between attendance and course grades for students with GPA higher than 2.67.

As can be surmised, few studies have examined the relationships among attendance policy, absenteeism, and class performance for students with different levels of prior academic achievement. The results of the few studies in this area have yielded inconsistent results. Therefore, the relationships are worthy of further study.

Based on the preceding discussion, we forward the following hypotheses and research questions:

Hypothesis 1(H1):Students who have fewer class absences would have higher grades.

H2: Students who are exposed to the compulsory attendance policy would have fewer absences than students who are exposed to the simple statement attendance policy.

H3: Students who are exposed to the compulsory attendance policy would have higher grades than students who are exposed to the simple statement attendance policy.

Research Question 1 (RQ1): Is the relationship between attendance policy and class absenteeism different for higher and lower academic achievers?

RQ2: Is the relationship between attendance policy and class performance different for higher and lower aca-demic achievers?

METHOD

Participants/Procedure

Participants were 212 students enrolled in either an MC or introduction to management information systems class at a

mid-sized public university in the Northeastern United States with about 12,000 students. The study included five sections of MC and four sections of MIS. The average class had about 24 students. The classes were taught by one of five professors, two MC professors and three MIS profes-sors. At the end of the semester, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire. Among the 141 participants who completed the questionnaire, 83 identified themselves as men and 58 as women. The participants, who reported an average GPA of 2.94 (SDD0.58) on a 4.00 scale, included 29 freshmen, 27 sophomores, 62 juniors, and 23 seniors. The average participant was 20.57 years old (SD D

4.55 years). The participants represented a diverse group of ethnicities, but most were Caucasian (nD107, 75.89%).

On the first day of class, students received a copy of the syllabus, which the instructor discussed. The syllabus served as the manipulation to create two conditions: simple state-ment and compulsory (see Table 1). The professor went over the syllabus, including the class attendance policy. All of the students in any given section of a class received the same attendance policy. To be more precise, MC instructor 1 taught one class that received the simple statement policy and two classes that received the compulsory policy. MC instructor 2 taught one class that received the simple state-ment policy and one class that received the compulsory pol-icy. MIS instructor 1 taught one class that received the compulsory policy. MIS instructor 2 taught one class that received the simple statement policy. MIS instructor 3 taught two classes that received the compulsory policy.

In order to control for as many confounding variables as possible, the MC instructors agreed to use the same text-book, the same syllabus (except for attendance policy), the same assignments and the same quizzes. Further, the MIS instructors all taught the same MIS course (introduction to MIS) and standardized key aspects of the course. In particu-lar, all of the instructors used the same text book, the con-tent was broken down into 70% on MIS concepts and 30% on practical, and all of the instructors used the same assess-ment methods, which include quizzes, cases, exams, practi-cal assignments and tests, current topics, and participation.

The fact that different instructors participated in the study is itself a potential confounding variable. Only one instructor (MC instructor 1) had classes in both conditions, but the unequal cell sizes and small sample make any com-parisons impossible. Snyder, Cistulli, and Forbus (2012) conducted a similar study using only one instructor and the relationship between absenteeism and performance was robust across experimental conditions. Moreover, in a sepa-rate study, Snyder et al. (2012) found that although levels of absenteeism may vary across instructors, the relationship between absenteeism and performance was robust. What the literature has made clear is that the link between atten-dance and performance is strong. Nonetheless, this poten-tial confound presents a limitation to the interpretation of this study’s results.

During the second week of the semester, students com-pleted a brief quiz that included information on the sylla-bus. One of the questions asked the students to identify the class attendance policy. The quiz served two purposes. First, it exposed students absent from the first day of class to the attendance policy. Second, it reinforced the manipu-lation. Each professor began collecting attendance data after the second week of class when the add–drop period ended for students. Students were absent if they did not receive permission from their professor to miss class. Per-mission to miss class was granted only if the student could demonstrate appropriate cause, such as an official univer-sity function, documented illness or court date.

Measurement and Instrumentation

Student grades, based on all the learning components of the course (MC or MIS), were calculated on a scale ranging from 0 to 100. In particular, students received a grade in the A range if they earned a score of 90 or greater, a grade in the B range if they earned between 80 and 89, a grade in the C range if they earned between 70 and 79, a grade in the D range if they earned between 60 and 69, and a grade of F if they earned fewer than 60. The average student earned a grade of 84.45 (SDD11.40).

RESULTS

The first hypothesis, H1, which predicted that those stu-dents who missed fewer classes would have higher grades, was supported by the data. In this study, the correlation between absences and grades was statistically significant (rD–.43,p <.001). The results obtained from our study are in agreement with the results obtained from previous studies relating absences and grades.

H2 predicted that those students who were exposed to the compulsory class attendance policy would have fewer absences than those students who were exposed to the sim-ple statement policy. We used a t-test to investigate this effect. In our study, we had 84 students in the simple statement condition and 127 students in the compulsory attendance policy condition. The t-test comparison for attendance showed that the average number of absences for students with the simple statement policy (m D 2.71)

was significantly higher than the average number of absen-ces for students with the compulsory attendance policy (m D 0.86 [see Table 2]). Therefore, the data supported

H2.

H3 posited that those students who were exposed to the compulsory attendance policy would have higher grades than those students who were exposed to the sim-ple statement policy. According to the results in Table 2, the data did not yield support for H3. We observed no differences in the average grade across conditions. This finding is discussed further below.

RQ1 and RQ2 asked about the relationship between attendance policy and both absenteeism and class grade for high versus low academic achievers. To provide answers to these questions, we had to create categories of students based on academic performance. To do so, we had to identify high, average and low performers. Many of the university’s prospective employers send out invitations to students for various internships or compet-itions. In these invitations, employers invariably ask for students with a GPA of 3.2 or better. Therefore, we used this GPA standard as an indicator for students who are considered high performers. In our business school, students have to maintain a GPA of 2.5 or better to remain in the program—students who fail to meet this standard will first receive a warning, then an academic probation and finally a dismissal. We used the 2.5 GPA as a cutoff for low performers. Thus, we divided our students into three groups: high performers (GPA of 3.2 or higher), average performers (GPA between 2.5 and 3.2), and low performers (GPA less than 2.5).

For each level of student performance, we compared the impact of the attendance policy on number of absen-ces and class grade. As per the overall group, a t-test

TABLE 2

Influence of Attendance Policy on Student Absences and Grades

Simple statement Compulsory policy

p

M SD M SD

Absences 2.71 3.00 0.86 1.23 <.001**

Grade 83.75 11.80 84.91 11.15 .47

**p<.01.

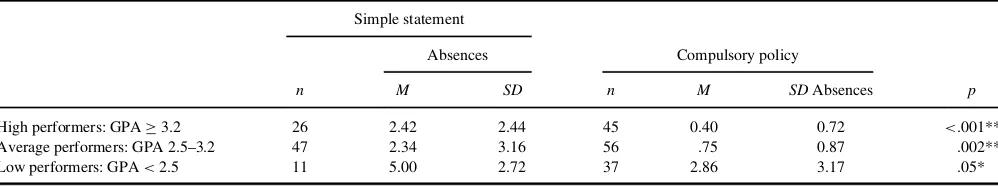

TABLE 3

Impact of Attendance Policy on Attendance by Past Academic Performance

Simple statement

Absences Compulsory policy

n M SD n M SDAbsences p

High performers: GPA3.2 26 2.42 2.44 45 0.40 0.72 <.001**

Average performers: GPA 2.5–3.2 47 2.34 3.16 56 .75 0.87 .002**

Low performers: GPA<2.5 11 5.00 2.72 37 2.86 3.17 .05*

*p.05, **p<.01.

436 J. L. SNYDER ET AL.

was used. Our results (see Table 3) showed that the attendance policy was related to the number of absences for students among the high performers (p D .0003), average performers (p D .0019), and low performers (p

D .0494). For the high performers, students in the sim-ple statement condition were absent an average of 2.42 class periods. In contrast, those in the compulsory atten-dance policy condition were absent an average of 0.40 class periods. For the average performers, the average number of absences for those in the simple statement condition was 2.34 compared to 0.79 for those with the compulsory attendance policy. For the low performers, the average number of absences across the two condi-tions is 5.00 and 2.86, respectively. Therefore, in response to research question 1, the data indicated that the relationship between attendance policy and class absenteeism was similar for students, regardless of their level of prior academic achievement. The compulsory attendance policy encourages fewer absences.

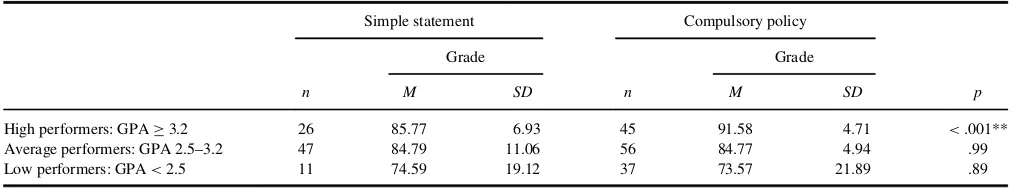

Finally, we tested the student’s grade for each perfor-mance level across the two conditions. The results are summarized in Table 4. Interestingly and unexpectedly, the attendance policy appeared to have a significant impact on class grade for only the high performers. For these students (GPA 3.2), students in the compulsory attendance policy group did significantly better than those in the simple statement group. The average score for students in the compulsory policy group was 91.58, compared to 85.77 for those in the simple statement pol-icy condition. There was no significant difference in average score for average performers and low perform-ers. For the second group (GPA between 2.5 and 3.2), the average scores were 84.79 (simple statement) and 84.77 (compulsory policy). For the low performers (GPA < 2.5), the average scores were 74.59 (simple statement) and 73.57 (attendance policy). Therefore, in response to research question 2, the data suggest that the relationship between attendance policy and class performance depends on the student’s level of prior aca-demic achievement. The compulsory policy is related to better class performance for high achievers, but not for the average and low achievers.

DISCUSSION

The present findings support previous research that has clearly demonstrated the positive association between class attendance and class performance (Chen & Lin, 2008; Clark et al., 2011; Crede, Roch, & Kieszczynka, 2010; Devadoss & Foltz, 1996; Longhurst, 1999; Lyubartseva & Mallik, 2012; Schmidt, 1983; Silvestri, 2003; Snyder et al., 2012; Thatcher et al., 2007; Thomas & Higbee, 2000). The prepon-derance of the existing social science research states that class performance of students who attend classes more fre-quently is evaluated more favorably than class performance of students who attend class less frequently. Universities that are under pressure to enhance graduation and retention rates may conclude that it is in both the students’ and institutions’ best interest to encourage class attendance. If so, then they must determine how best to do it. In this study, we wanted to know if requiring class attendance is a good route to reducing absenteeism and increasing grades. In particular, we explored the influence of a compulsory class attendance policy on class absenteeism and class performance.

To answer this question, we conducted a quasiexperiment in which students in managerial communication and man-agement information systems classes were exposed to a syl-labus with either a compulsory attendance policy or a simple statement attendance policy. The compulsory policy aimed to compel attendance by using a grade-related punishment for absences. The simple statement indicated that attendance was expected, but it offered neither a reward nor a punish-ment. We evaluated the effects of these policies on absentee-ism and grades for students as a whole and for three student cohorts grouped by previous GPA performance: high achiev-ers, medium achievachiev-ers, and low achievers.

The results of our study—when examined without grouping into GPA cohorts and without including the sylla-bus policy variable—confirm the long-standing outcome linking class attendance to class performance. Also, not very surprisingly, those students exposed to the compulsory attendance policy had fewer absences than those students who received the simple statement attendance policy. The threat of final grade reduction seems to accomplish its intent of encouraging students to come to class.

TABLE 4

Impact of Attendance Policy on Grades by Past Academic Performance

Simple statement Compulsory policy

Grade Grade

n M SD n M SD p

High performers: GPA3.2 26 85.77 6.93 45 91.58 4.71 <.001**

Average performers: GPA 2.5–3.2 47 84.79 11.06 56 84.77 4.94 .99

Low performers: GPA<2.5 11 74.59 19.12 37 73.57 21.89 .89

**p<.01.

Although absenteeism was related to class grades and attendance policy was related to absenteeism, the present results suggest that the policy’s direct effect on class grades depended upon the student’s prior academic performance. This result is somewhat surprising and in contradiction to

H3. Even though the average number of absences for stu-dents in the compulsory attendance policy was lower than their counterparts, the average aggregate class grades for those in the compulsory condition did not differ signifi-cantly from aggregate class grades for those in the simple statement condition. If a compulsory attendance policy reduces absenteeism, and class attendance increases perfor-mance, then why is there no direct relationship between a compulsory attendance policy and class performance? Although this question warrants more investigation, we can preliminarily speculate that the relationship between policy and performance may be moderated by one or more varia-bles. In other words, the relationship is not as straightfor-ward as we originally believed. The data from this study suggest at least two possible explanations for whyH3 was not supported.

One possible explanation of the findings may be the fact that fewer students were in the simple statement condition. Of particular note is the fact that only 11 students were low achievers in the simple statement condition. There were sub-stantially more low-achieving students in the compulsory condition (nD37). Only 13% of the students in the simple statement condition were low achievers, and 27% of the stu-dents in the compulsory condition were low achievers. Given the difference in these proportions, the low achievers in the compulsory condition may have had a bigger effect on the overall average grade than the low achievers in the simple statement condition. Therefore, one explanation of the coun-terintuitive finding is that it is simply related to the unequal effect of the low achievers on average grade.

The student cohort analysis of high, medium, and low achievers offers another possible explanation. When the relationship between a compulsory policy and final course grades is analyzed separately for the three cohorts (see Table 3), an interesting and unexpected picture emerges: a compulsory policy does have a positive impact on grades, but only for high achievers. This result suggests that the benefit of improved attendance in those sections with a compulsory policy appears to be limited to students who already have relatively high GPAs and therefore are in the least need to improve their academic performance—to stay in school (retention) and to graduate. Putting it differently still, all student cohorts—low, medium, and high achiev-ers—when encouraged with a compulsory attendance pol-icy came to class more often, but only the high achievers ended up getting better grades. This finding was unexpected and deserves further study. For now, we can speculate about reasons for this high-achiever effect.

The relatively higher positive impact of improved atten-dance on exam grades by high-ability students has been

previously identified by Dollinger et al. (2008). Their study focused on factors that best account for academic suc-cess—and their definition of high-ability students is broader than our definition. However, similar to our findings, they concluded that class attendance benefits most those students who are the most able.

In looking for possible explanations of the high achievers difference described previously, one comes across research done on the big five personality traits and on the finding that conscientiousness is a good pre-dictor of GPA, and, therefore, of performance (Busato, Prins, Elsout, & Hamaker, 2000; Chamorro-Premuzic & Furnham, 2003; Conard, 2006; Dollinger & Orf, 1991; Fumham & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2004; Lounsbury, Sundstrom, Loveland, & Gibson, 2003; Martin, Montgomery, & Saphian, 2006; Murgrave-Marquart, Bromley, & Dalley, 1997; Paunonen & Ashton, 2001; Peterson, Casillas, & Robbins, 2006). The results of our study appear to support the inference that there is a con-scientiousness-performance link.

Even among high achievers, however, there may be differences in levels of conscientiousness that could influence performance. Among the high achievers, the attendance policy appeared to affect the participants’ conscientiousness about how missing classes could nega-tively impact their grades. For them, it is important to minimize any actions that could affect their grades and perhaps are more likely to internalize the impact of atten-dance on performance. Students who are more conscien-tious are more likely to internalize the potential impact of compulsory attendance policy and modify their behav-ior accordingly. Therefore, it is possible to have two high-achieving students, one who is high on conscien-tiousness and one who is low on conscienconscien-tiousness. The conscientious student may be more likely to internalize the impact of attendance on performance. The less con-scientious student may miss fewer classes, but may not internalize the reason behind the policy—improved per-formance. In fact, less conscientious students may be in class but more likely to be less actively engaged in the class. If true, however, this conclusion also implies that that conscientiousness-performance link is not a contin-uum, for the data do not confirm it for low and medium achievers. The search for an answer to this counterintui-tive finding is worthy of further investigation.

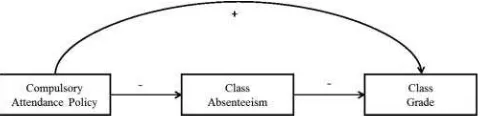

One limitation of the present study was the sample and sampling procedure. A convenience sample of students was used and, thus, may not be representative of the larger stu-dent population. This constraint was largely the result of the nature of the study, but it is still worthy of mention. The sample size was relatively small. Given the nature of the present findings, a larger scale study with more participants would yield itself to more sophisticated analysis, such as path modeling. The present findings suggest a fully medi-ated hypothesized model for low and medium achievers in

438 J. L. SNYDER ET AL.

which compulsory attendance policy exhibits a direct effect on absenteeism, and absenteeism has an effect on grade (see Figure 1). For high achievers, the hypothesized model would feature a partially mediated relationship between compulsory attendance policy and grade (see Figure 2).

Future studies might include students enrolled in courses in other disciplines that are both in and outside of schools of business, while controlling for professorial differences. In fact, future studies should consider professorial differen-ces and their impact on attendance and performance. As we mentioned above, the fact that multiple instructors partici-pated in the study introduced a potential confounding vari-able. However, Snyder et al. (2013) conducted a similar study using only one instructor teaching one class for all sections. The relationships among policy, attendance and performance were comparable to the current results. It is, nevertheless, possible that students may respond to atten-dance policies differently, depending upon the instructor. For instance, certain instructor behaviors, such as verbal aggressiveness, have been linked to student motivation (Myers, 2002) and student perceptions of the learning envi-ronment (Rocca, 2004). Other relationships that may be investigated include the relationship between GPA and class absences, the relationship between GPA and course grade, the correlation between class absences and course grade and the relationships among GPA, class absences, and employment.

The current study utilized a single manipulation of the class attendance policy. Researchers should consider alter-native ways to encourage class attendance. For example, Snyder et al. (2012) used Cialdini’s (2001) social proof principle to encourage class attendance. Social influence can be a powerful trigger for human behavior. With that in mind, researchers could look at the impact of testimonials from former students on class attendance. This could be done in several ways, including prerecorded videos that stu-dents view during the semester. Another method worth investigation is the use of quizzes or other forms of assess-ment at the beginning each class.

Future researchers should further explore the intriguing link between conscientiousness and performance. The pres-ent study has shown that a compulsory attendance policy leads to higher attendance for all students, but the higher attendance reached this way leads to higher grades only for the high achievers. Why didn’t we see improved perfor-mance across experimental conditions? Could there be other variables—more significant than conscientiousness— playing a role? Does innate ability trump hard work?

REFERENCES

Billington, P. J. (2008). Impact of student attendance on course grades. Journal of American Academy of Business,12, 256–262.

Busato, V. V., Prins, F. J., Elshout, J. J., & Hamaker, C. (2000). Intellectual ability, learning style, personality, achievement motivation and

aca-demic success of psychology students in higher education.Personality

and Individual Differences,29, 1057–1068.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A (2003). Personality predicts aca-demic performance: Evidence from two longitudinal university samples. Personality and Individual Differences,37, 319–338.

Chan, K., Shum, C., & Wright, D. (1997). Class attendance and student

performance in principles of finance.Financial Practice and Education,

2, 58–65.

Chen, J., & Lin, T. F. (2008). Class attendance and exam performance: A

randomized experiment.Journal of Economic Education,39, 213–227.

Cialdini, R. B. (2001). Harnessing the science of persuasion. Harvard

Business Review,79, 72–79.

Clark, G., Gill, N., Walker, M., & Whittle, R. (2011). Attendance and

per-formance: Correlations and motives in lecture-based modules.Journal

of Geography in Higher Education,35, 199–215.

Conard, M. A. (2006). Aptitude is not enough: How personality and

behav-ior predict academic performance.Journal of Research in Personality,

40, 339–346.

Crede, M., Roch, S. G., & Kieszczynka, U. M (2010). Class attendance in

college: A meta-analytic review of the relationship of class attendance

with grades and student characteristics. Review of Educational

Research,80, 272–295.

Devadoss, S., & Foltz, J. (1996). Evaluation of factors influencing student

class attendance and performance. American Journal of Agricultural

Economics,78, 499–507.

Dobkin, C., Gil, R., & Marion, J. (2007).Causes and consequences of

skip-ping class in college[Mimeo]. Santa Cruz, CA: University of California Santa Cruz.

Dollinger, S. J., Matyja, A. M., & Huber, J. L. (2008). Which factors best account for academic success: Those which college students can control

or those they cannot?Journal of Research in Personality,42, 872–885.

Dollinger, S. J., & Orf, L.A. (1991). Personality and performance in

“personality”: Conscientiousness and openness.Journal of Research in

Personality,25, 276–284.

Fumham, A., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2004). Personality and

intelli-gence as predictors of statistics examination grades.Personality and

Individual Differences,37, 943–955.

Hunter, S., & Tetley, J. (1999, July).Lectures. Why don’t students attend?

Why do students attend?Paper presented at the HERDSA Annual Inter-national Conference, Melbourne, Australia.

Longhurst, R. J. (1999). Why aren’t they here? Student absenteeism in a

further education college.Journal of Further and Higher Education,23,

61–80.

Lounsbury, J. W., Sundstrom, E., Loveland, J. M., & Gibson, L. W. (2003). Intelligence, “big five” personality traits, and work drive as predictors of

course grade.Personality and Individual Differences,35, 1231–1239.

FIGURE 2. The relationship among compulsory policy, absenteeism, and class grade for high achievers.

FIGURE 1. The relationship among compulsory policy, absenteeism, and class grade for low and medium achievers.

Lyubartseva, G., & Mallik, U. P. (2012). Attendance and student

perfor-mance in undergraduate chemistry courses.Education,133(1), 31–34.

Marburger, D. R. (2006). Does mandatory attendance improve student

per-formance?The Journal of Economic Education,37, 148–155.

Martin, J. H., Montgomery, R. L., & Saphian, D. (2006). Personality, achievement test scores, and high school percentile as predictors of

aca-demic performance across four years of coursework. Journal of

Research in Personality,40, 424–431.

Moore, R. (2005). Attendance: Are penalties more effective than rewards? Journal of Developmental Education,29(2), 26–32.

Moore, R., & Jensen, P. A. (2008). Do policies that encourage better atten-dance in lab change students’ academic behaviors and performances in

introductory science courses?Science Educator,17, 64–71.

Murgrave-Marquart, D., Bromley, S. P., & Dalley, M. B. (1997). Personal-ity, academic attribution, and substance use as predictors of academic

achievement in college students.Journal of Social Behavior and

Person-ality,12, 501–511.

Myers, S. A. (2002). Perceived aggressive instructor communication and

student state motivation, learning, and satisfaction. Communication

Reports,15, 113–121.

Park, K. H., & Kerr, P. M. (1990). Determinants of academic performance:

A multinomial logic approach. Journal of Economic Education, 21,

101–111.

Paunonen, S. V., & Ashton, M. C. (2001). Big five predictors of academic

achievement.Journal of Research in Personality,35, 78–90.

Peterson, C. H., Casillas, A., & Robbins, S. B. (2006). The Student Readi-ness Inventory and the big five: Examining social desirability and

col-lege academic performance.Personality and Individual Differences,41,

663–673.

Rocca, K. A. (2004). College student attendance: Impact of instructor

imme-diacy and verbal aggression.Communication Education,53, 185–195.

Rodgers, J. R. (2002). Encouraging tutorial attendance at university did not

improve performance.Australian Economic Papers,41, 255–266.

Schmidt, R. M. (1983). Who maximizes what? A study in student time

allocation.American Economic Review,73, 23–28.

Silvestri, L. (2003). The effect of attendance on undergraduate methods

course grades.Education,123, 483–486.

Snyder, J., Cistulli, M., & Forbus, R. (2012). Attendance policies, student

attendance, and instructor verbal aggressiveness.Journal of Education

for Business,87, 145–161.

St. Clair, K. L. (1999). A case against compulsory class attendance policies

in higher education.Innovative Higher Education,23, 171–180.

Thatcher, A., Fridjhon, P., & Cockcroft, K. (2007). The relationship between lecture attendance and academic performance in an undergraduate

psy-chology class.South African Journal of Psychology,37, 656–660.

Thomas, P. V., & Higbee, J. L. (2000). The relationship between

involve-ment and success in developinvolve-mental algebra.Journal of College Reading

and Learning,30, 222–232.

Wyatt, G. (1992). Skipping class: An analysis of absenteeism among

first-year college students.Teaching Sociology,20, 201–207.

440 J. L. SNYDER ET AL.