Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Widjojo Nitisastro and Indonesian development

Peter McCawley

To cite this article: Peter McCawley (2011) Widjojo Nitisastro and Indonesian development, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 47:1, 87-103

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2011.556061

Published online: 15 Mar 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 195

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/11/010087-17 © 2011 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2011.556061

Review Article

WIDJOJO NITISASTRO AND INDONESIAN DEVELOPMENT

Peter McCawley

Australian National University

Widjojo Nitisastro (2010) Pengalaman Pembangunan Indonesia: Kumpulan Tulisan dan Uraian Widjojo Nitisastro [The Experience of Development in Indonesia: A Collec-tion of the Writings of Widjojo Nitisastro], Penerbit Buku Kompas [Kompas Book Publishing], Jakarta.

Widjojo Nitisastro is one of Indonesia’s best-known economic policy makers. Much has been written by others about his role as a top adviser over more than three

dec-ades. This collection of his own essays helps ill out the picture. Seven main policy themes may be identiied: the role of economic growth in helping overcome mass

poverty; the need for economic policy makers to pay close attention to risk manage-ment and be constantly ready to respond to economic shocks; the importance of strong leadership and discipline in government; the need to scrutinise investment programs closely; the high priority to be given to borrowing programs and debt management; the role of the price mechanism; and the management of Indonesia’s relations with the international community. Strong messages about growth, leader-ship and stability permeate the essays. The collection is a valuable contribution to the literature on economic policy making in developing countries.

INTRODUCTION

In the wake of the dramatic political events of September 1965 and their awful aftermath in 1966, Indonesia faced urgent economic problems at almost every turn.1 And as is well known, into the gap stepped a small group of key economic advisers who became known as the ‘Berkeley Maia’.2 The acknowledged leader

of the group was the Dean of the Economics Faculty at the University of Indo-nesia, Professor Widjojo Nitisastro. Over the next three decades Widjojo and his

1 Elson (2001: ch. 6) discusses the events of the period.

2 Details of the early role played by the Berkeley Maia group in 1966 are set out in the introduction to Arsjad Anwar, Thee and Azis (1992); see also Thee (2002: 195–6). The group is generally listed as consisting of Widjojo, Ali Wardhana, Mohammad Sadli, Emil Salim, and Subroto. They are also referred to as ‘economic technocrats’, and during the next few

years other economic advisers to the government, such as Rachmat Saleh, Ariin Siregar,

colleagues, including many outside of the original group, guided the Indonesian economy with extraordinary skill through both good times and bad.3

The role that Widjojo Nitisastro played in Indonesia’s economic development between 1966 and 1998 has been widely celebrated. Within Indonesia, he is uni-versally known across the policy-making elite, the economics profession and the development aid community. In 2007 a remarkable list of senior Indonesian policy makers and advisers collaborated to produce a warm and valuable collection of articles about their experiences of working with Widjojo (Arsjad Anwar, Ananta and Kuncoro 2007a). In elite international policy-making circles he is among the most respected economic statesmen of Southeast Asia since the Second World War. The roll-call of eminent international leaders who have paid tribute to his work includes Manmohan Singh, Larry Summers, Julius Nyerere, Noboru Take-shita, Cesar Virata, Michel Camdessus, Marshall Green and many others (Arsjad Anwar, Ananta and Kuncoro 2007b).

Among the characteristics generally required of a top government policy maker is the ability to work well with colleagues and draw the best efforts out of a close

team. Widjojo’s skill in coordinating the policies of the Berkeley Maia group is

legendary. One of his close colleagues, Emil Salim, described his role as follows:

Looking back on my experience as a cabinet minister for over two decades ... it was Widjojo who was the real architect of the economic policies of the New Order. He was the dalang, or puppeteer, who directed the play, while we, the other economic technocrats, were the players, the wayang. We used to call him lurah (village head), and we still do. Widjojo was able to carry out his economic policies because Soehar-to trusted him; the president knew that he did not have a ‘hidden agenda’. Widjojo was also able to rely on us, his fellow economists, because we all shared similar views on the need to pursue sound economic policies (Salim 2003: 209).

Much has been written by Widjojo’s friends and colleagues about the role he played as a top adviser. But what has been somewhat lacking is an accessible record of Widjojo’s own views about economic policy during the period. With the publication of this volume (Nitisastro 2010), we now have a valuable collection of

articles, reports and commentary selected by Widjojo himself. It helps to ill out

the picture of his role in economic policy making in Indonesia, and is a contribu-tion to the literature on economic policy making in developing countries.

THE COLLECTION

Pengalaman Pembangunan Indonesia provides a rich body of commentary on policy issues across the entire period of Widjojo’s career as a key adviser. With the excep-tion of one early (1963) article, the scope of the collecexcep-tion coincides almost exactly with the Soeharto era. A batch of articles prepared in 1966 records in detail the

3 A brief summary of Widjojo’s career is given in Arsjad Anwar, Ananta and Kuncoro (2007b: xvii). Widjojo held ministerial rank in successive Indonesian cabinets for most of the 1970s and until 1983, when he chose not to sit as a minister in the Fourth Development

Cabinet. He continued to be very inluential as one of President Soeharto’s closest advis -ers throughout the rest of the 1980s, and worked closely with the president until Soeharto

thorough measures taken to ensure that a ‘rational’ approach to economic policy (to use Widjojo’s words) would replace the policies pursued in the early 1960s under then President Soekarno. The other chapters survey a wide sweep of eco-nomic policy issues covering the 1970s, the 1980s and much of the 1990s, up to the end of the Soeharto ‘New Order’ era in 1998.

There are several ways of viewing the scope of the volume. One is to note the sections into which Widjojo has grouped the chapters:

• Indonesian Development Planning

• Implementation of Indonesian Development

• Facing Various Economic Crises

• Tackling Problems of External Debt

• Equity in Development

• Indonesia and the World

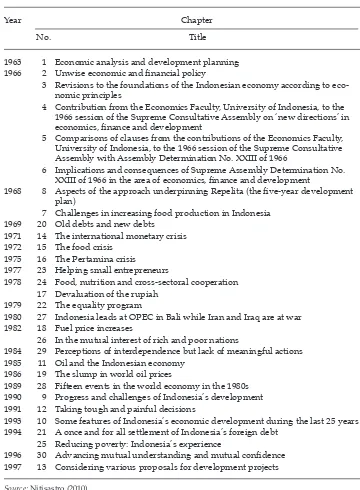

A more complete picture, which gives a sense of the movement in policy as events unfolded over the period, can be seen in the list of chapter headings arranged by date of original publication (table 1).

To survey the remarkable breadth of the collection it will be useful to consider the main themes that recur throughout the chapters, and to outline the distinc-tive view that Widjojo, as an eminent policy adviser from the developing world, presents on some of the issues on today’s global development policy agenda. This

article also relects briely on some matters that the collection does not cover.

POLICY THEMES

Of the various themes to which Widjojo returns in his three-decade coverage of policy making, a few underpin much of the discussion. They are simple, direct

messages, probably familiar to all good policy makers. It is perhaps signiicant

that, although his training and professional life has focused mainly on economic policy, Widjojo has taken a close interest in demographic issues as well.4 His view of the scope of policy thus tends to go well beyond the speciics of macro- or

microeconomic policy. For example, in a 1990 essay, ‘Progress and challenges of development in Indonesia’, he outlines 10 main topics that he saw as important at the time:

• population in Java

• debt management

• economic reform and policy improvement

• poverty alleviation

• protection of the environment

• food self-suficiency

• development of human resources

• expansion of the labour market

• business growth and social justice

• the role of government and regulation

This approach to policy making underlines Widjojo’s concern not just with the

spe-ciics of economic policy but with a much broader view of the development process

across Indonesia as a whole. In this, he shared many of the views of his colleague Professor Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, who emphasised the importance of seeing Indonesia’s development challenges within a long-term context (Esmara 1987).

TABLE 1 Chronological Listing of Chapters

Year Chapter

No. Title

1963 1 Economic analysis and development planning 1966 2 Unwise economic and inancial policy

3 Revisions to the foundations of the Indonesian economy according to eco-nomic principles

4 Contribution from the Economics Faculty, University of Indonesia, to the 1966 session of the Supreme Consultative Assembly on ‘new directions’ in

economics, inance and development

5 Comparisons of clauses from the contributions of the Economics Faculty, University of Indonesia, to the 1966 session of the Supreme Consultative Assembly with Assembly Determination No. XXIII of 1966

6 Implications and consequences of Supreme Assembly Determination No.

XXIII of 1966 in the area of economics, inance and development

1968 8 Aspects of the approach underpinning Repelita (the ive-year development plan)

7 Challenges in increasing food production in Indonesia 1969 20 Old debts and new debts

1971 14 The international monetary crisis 1972 15 The food crisis

1975 16 The Pertamina crisis 1977 23 Helping small entrepreneurs

1978 24 Food, nutrition and cross-sectoral cooperation 17 Devaluation of the rupiah

1979 22 The equality program

1980 27 Indonesia leads at OPEC in Bali while Iran and Iraq are at war 1982 18 Fuel price increases

26 In the mutual interest of rich and poor nations

1984 29 Perceptions of interdependence but lack of meaningful actions 1985 11 Oil and the Indonesian economy

1986 19 The slump in world oil prices

1989 28 Fifteen events in the world economy in the 1980s 1990 9 Progress and challenges of Indonesia’s development 1991 12 Taking tough and painful decisions

1993 10 Some features of Indonesia’s economic development during the last 25 years 1994 21 A once and for all settlement of Indonesia’s foreign debt

25 Reducing poverty: Indonesia’s experience

1996 30 Advancing mutual understanding and mutual conidence 1997 13 Considering various proposals for development projects

Economic growth and mass poverty

The irst main theme that Widjojo emphasises, especially in the earlier years, is

the challenge of mass poverty in Indonesia and the vital need for good develop-ment policies to begin an assault on the problem. His concern for the parlous state that Indonesia was in during the mid-1960s, and the urgency of fostering ‘the slow return of sanity to government decision making’, as Jamie Mackie has put it (McCawley and colleagues 2002: 166), is particularly evident in Widjojo’s early articles. But a continuing emphasis on widespread poverty, and the need for sustained economic growth to overcome it, remains a central theme throughout the period covered by the collection. In 1994, for example, at an IMF–World Bank conference in Spain, he outlined Indonesia’s anti-poverty programs in a paper on ‘Reducing poverty: Indonesia’s experience’ (ch. 25). He noted the importance, in the Indonesian context, of promoting rural development by investing in pri-mary schools, health clinics, nutrition and family planning programs, and rural

infrastructure such as roads, irrigation systems and lood control structures at

the village level.

For Widjojo, the link between tackling poverty and developing sound policies is clear. Again and again he emphasises the need for commonsense policy. He urges policy makers constantly to consider ways of eliminating waste in govern-ment; to husband scarce resources; to make more ‘rational’ decisions than had been the case in the 1950s and early 1960s; and to pay proper attention to sensible macro- and microeconomic policies.

It seems in retrospect that in irmly supporting these principles, Widjojo and his close colleagues in the Berkeley Maia, such as Ali Wardhana, set a tradition that

has endured among many Indonesian policy technocrats to the present day.5 A

long line of senior economic policy makers has followed their lead, including the current vice president, Boediono; the trade minister, Mari Pangestu; the planning

minister, Armida Alisjahbana; the former inance minister, Sri Mulyani Indrawati; earlier policy makers such as Ariin Siregar, J.B. Sumarlin, Radius Prawiro, Saleh Aiff, Suhadi Mangkusuwondo and J. Soedradjad Djiwandono; and more recent

advisers such as Anggito Abimanyu, M. Chatib Basri, Moh. Ikhsan, Raden Pard-ede and others.

Some observers, both within Indonesia and overseas, argue that too many of Indonesia’s senior economic policy makers today are over-cautious. A criticism

sometimes made of them, as of the Berkeley Maia group before them, is that they

are not adventurous enough. But it is surely a great strength of several genera-tions of technocratic policy makers in Indonesia that they have adopted Widjojo’s approach of cautiously examining all main proposals that come to them from the viewpoint of Indonesia’s national interest, and of being reluctant to experiment with policy unless the case for change is strong.

Risk management

A second dominant theme, consistent with the irst, is the importance of risk

management. Again and again, Widjojo warns of the need for Indonesia’s policy makers to be waspada (cautious, alert or on guard) and to be ready to respond to unexpected events (which, he emphasises, can change conditions for the worse as well as for the better). It is clear throughout the book that Widjojo is thinking of both domestic and external shocks. His fascinating chapters on the 1972–73 food crisis and the Pertamina crisis of 1975 are about domestic shocks that dominated Indonesia’s policy agenda for months at the time they occurred. But much of the discussion – about oil prices, foreign exchange rates and international borrow-ings – relates to international shocks. Running through this material are several recurring sub-themes.

First, Widjojo is concerned about the uncertainty of the international environ-ment for developing countries, and about how Indonesia seems to be continually

buffeted by international events. The clearest example is the dramatic luctuation

in oil prices during the 1970s and 1980s. Other international events that contrib-uted to uncertainty for Indonesian policy makers included the dramatic realign-ments of international foreign exchange rates between the Plaza Accord in 1985 and the Louvre Accord in 1987.

Second, Widjojo notes in a pragmatic way that decisions taken by senior policy

makers in distant rich countries can have signiicant backwash effects on devel -oping countries. In commenting on the ‘Nixon Shock’ of August 1971 – when the United States declared, in effect, its abrogation of the Bretton Woods agreement on international exchange rate arrangements, which had applied since 1944 – he noted that there were ‘... serious implications for developing countries’, and that

the changes ‘… in the short-term would disadvantage prospects for Indonesia’s

exports’ (p. 265).

Widjojo also stresses the need for Indonesia to diversify its sources of export rev-enues to guard against the risks of dependence on any single source. He urges that

‘… Indonesia must give high priority to efforts to increase foreign exchange rev -enues from the export of goods and services outside the oil and gas sector’ (p. 388).

Discipline in government

A third theme anticipates the current emphasis on the importance of governance in developing countries. Widjojo believes that emerging country leaders must be

prepared to take dificult decisions. In a chapter on this subject he says (p. 229)

that

… it is necessary for leaders in developing countries always to be vigilant and never

to have doubts about moving to take necessary decisions, no matter how tough and painful they may be. 6

And this was clearly one aspect of Soeharto’s approach to government of which Widjojo approved. He says ‘President Soeharto as leader never drew back from

taking tough and painful decisions, no matter how … dificult they were’.7

6 All main quotations from Indonesian are translations by the author of this review.

7 Widjojo’s colleague Emil Salim also emphasises Soeharto’s willingness to take dificult

Widjojo is irm on the importance of disciplined decision making. He is critical

of what he calls ‘non-rational’ decision making during the period of the Soekarno presidency. ‘We can’t just do this and that’, he says, speaking of the ad hoc approach to public policy in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Decisions, he empha-sises, must be ‘rational’. He is also critical of the lack of discipline and rationality in other developing countries:

Failure to overcome … challenges in … developing countries sometimes arises be -cause leaders fail to set consistent priorities when considering the measures they plan to take. Sometimes the leaders are unable to agree among themselves on prior-ities. Or if they do reach agreement on the priorities, sometimes they do not adhere to them, or fail to implement them. The result is that programs that were not seen as priorities are adopted, while other activities originally accorded high priority are pushed aside. In effect, activities are being carried out without any sense of priori-ties (p. 234).

Widjojo also emphasises the importance of discipline in the implementation of policies. In 1966, when he and his colleagues were playing an increasing role in efforts to reform the approach to economic policy making, he argued that

it would be best for us all to recognise that improvements in the economic situation will not be realised through speeches, symposiums, seminars and so on, but only

through concrete actions. … [T]he problem we need to tackle is how the good inten -tions of government can be translated into reality (pp. 46–7).

Expanding on this theme, he said:

No matter how good particular decisions are, they will mean little unless they are translated into action. Unless this happens, there will just be disappointment. In

practice, it is not unusual for steps to be taken that are said to relect the imple

-mentation of particular decisions but that do not, in fact, relect the real intent of

those decisions at all. Indeed, it sometimes happens that the particular steps that

are taken distort and undermine the original decisions, yet they are justiied with

various spurious explanations (p. 120).

On the basis of this approach, Widjojo and his colleagues argued through-out 1966 for widespread reforms to government. Proposals mentioned (ch. 6) included greatly improved budgetary procedures; tighter supervision of govern-ment expenditures; strengthening of regulatory organisations such as the Finan-cial Supervisory Agency (Badan Pengawas Keuangan); and a streamlining and

simpliication of government procedures. Only some of these reforms came to be

implemented in the ensuing years, but those that were (such as more disciplined budgetary procedures) led to major improvements in government management, while those that were not (such as streamlined government) remain widely

recog-nised as part of the uninished agenda of government reform in Indonesia.

One of the clearest examples of the sort of discipline Widjojo favoured – though imposed at a very late stage in the process – was the action the government took in response to the Pertamina crisis in 1975. There had been much public comment

in Indonesia for ive years or more (Mackie 1970) about the free-wheeling ways in

incurred serious debt problems by undertaking massive short-term borrowings. When international credit markets tightened, the company found itself unable to service its debts.

In response to this crisis the government, at the urging of Widjojo and other top

economic advisers, inally clamped down on Pertamina (Sadli 2003: 134). It fell to

Widjojo, as Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs and chair of the National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas), to make a statement to the parliament on the situation. His message was frank and tough (ch. 16). Widjojo outlined steps that he diplomatically described as ‘measures to help overcome Pertamina’s

dif-iculties’, and actions designed to protect both the nation’s inances and the bal -ance of payments. In addition, he announced a range of new measures to bring Pertamina’s operations under tighter regulatory control: its borrowings would be much more closely restricted; its entire investment program would be re-examined; stricter internal administration would be required from its management; and a

revision of its inancial arrangements would be undertaken to ensure that a much higher share of the company’s proits was paid into government revenues.

Pertamina’s 1975 debt problems represented an acute crisis for the govern-ment.8 The crisis dominated public policy debate in Indonesia for over a year.

It seems obvious that action should have been taken much earlier, but President Soeharto, for his own reasons, was reluctant to impose controls on the company. As a result, the economic advisers within government who were pressing for tighter regulation, including Widjojo and his colleagues, had no choice but to bide their time. It can be argued that the Pertamina debacle was an example of lack of discipline within government. However, Widjojo and other economic advisers would have contended that the crisis showed precisely why their arguments in favour of strict discipline in government were so important.

Investment programs

Another of the main themes to which Widjojo frequently returns, consistent with his emphases on ‘rationality’ and risk management, is the need for careful over-sight of investment programs. Policy makers, he says, must carefully consider the risks inherent in proposed investments, and the pros and cons of public or private sector projects that involve large-scale borrowings. Widjojo is instinctively cau-tious in evaluating large projects. He warns that things can go badly wrong when the basic principles of ‘check and recheck’, as he puts it, are neglected. And he is sharply critical of leaders in other developing countries who implemented careless public investment programs; for example, he says that ‘[i]n the past, Ghana bor-rowed from various sources and used the money for unproductive purposes. This is scarcely different from what we did at the same time’ (p. 401). And he observes, doubtless recalling the circumstances in Indonesia in the early 1960s, that

[i]n some countries, there are leaders who want to build everything at once. All sorts

of large projects are implemented at the same time, as if there were no inancing or

other resource constraints. The result of this approach is that many plans end up

not being implemented, many projects are neglected, and inlation can begin to rage

entirely out of control (p. 234).

He discusses the implications of careful project planning at some length in his essay on the approach of former Vice President Sudharmono (1987–93), who exercised tight control over public investment programs (ch. 13). Sudharmono, Widjojo explains, provided strong and effective discipline by asking a series of straightforward questions about public investment proposals that came before him. The most important of these were:

• Is the project necessary?

• Does it need to be so large? Is it not possible to build a smaller project?

• Is it necessary now? What is the urgency? Are there not more urgent alternative activities?

• Can the costs be reduced? Has everything possible been done to reduce the costs?

• Have experts reviewed the feasibility study? Can we see the results of the review?

There is little doubt that Widjojo had in mind the need to curb the ambitions of

inluential presidential advisers who were close to President Soeharto. The eco -nomic advisers in Jakarta in the 1970s and 1980s often found themselves engaged

in policy battles with such well-known igures such as Ibnu Sutowo and B.J.

Habibie, the respective leaders of Pertamina and of a group of high-tech aero-nautical companies in Bandung.9 The engineering advisers within government,

who supported the approach of these people, favoured a development policy for Indonesia that focused on state-sponsored assistance for ‘strategic industries’. But too often, in the view of Widjojo and the other economic technocrats, the grand plans endorsed by the engineers were expensive and risky.10

Widjojo’s irm view is that policy makers should avoid over-conidence in

supporting either public or private investment. He made some prescient

com-ments on the issues at stake in 1997 – just months before the Asian inancial crisis

unfolded, delivering a series of blows to the economy that set back development

9 B.J. Habibie, later president of Indonesia (1998–99), was responsible for a group of 10

state-owned irms operating in the airlines and aeronautical sector, one of the best known

being IPTN (Industri Pesawat Terbang Nusantara, literally ‘[Indonesian] Archipelago Air-craft Industry’).

10 The differences of view between the economic and the engineering advisers are

re-lected in a September 1976 interview I had with Ibnu Sutowo in Jakarta. Ibnu mentioned

disagreements that had arisen between him and Widjojo several years earlier over plans for a large fertiliser project. Ibnu had proposed the construction of a fertiliser plant drawing on

Pertamina resources. Widjojo was cautious and suggested that Indonesia seek to inance

for almost a decade. Endorsing Sudharmono’s sceptical approach to showcase

projects, Widjojo argued that unless policy makers avoid over-conidence,

… development will be derailed and lose direction, resulting in economic decline …

This is what happened in various developing countries, especially in Latin America.

When things were dificult on the economic front, and when their capacities were limited, these countries were cautious and held irm to development priorities. But when things improved, a sense of over-conidence developed that led them to

drop their guard. They competed to promote projects across various sectors, and

governments no longer held irmly to strict development priorities. The result was

that they over-reached themselves and an economic crisis eventuated. This is what happened in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, and especially Mexico.

A similar process has often occurred in the private sector in these countries. … [Companies] have inanced their activities with international borrowings which, oficially, are not accompanied by government guarantees. However, because inter -national loans are used to support projects that are closely connected with the gov-ernment, or with large government-owned enterprises, an indirect government guarantee gets built into these activities. And when a foreign debt crisis looms, a large share of the private sector debts – including short-term debts – get transferred

to the government. This is what occurs when we fail to pay suficient attention to

the details of implementation of development programs (p. 254).

From one point of view, the principles Widjojo outlines are obvious. But from another, his messages are crucial ones because of the frequency of attempts to brush them aside. There is a propensity in many countries for leaders who claim to have vision – and for the enthusiastic lobbyists who line up behind them – to support expenditure of public monies on investments of doubtful value. And there has been no shortage of costly projects in Indonesia, to many of which Widjojo refers in his collection.11

Borrowing and debt

Another of the collection’s main themes is the need for careful debt management. Widjojo constantly emphasises that policy makers must be careful in taking on for-eign borrowings. Nationalist and populist commentators in Indonesia sometimes

accused the economic technocrats of being too willing to sacriice Indonesian

interests in order to win praise from the international community. The techno-crats were also accused of having been indoctrinated with neo-liberal ideology in western universities. But it is clear that Widjojo shares the caution that many Indonesian policy makers and commentators feel about opening the Indonesian economy too readily to international market forces. In various places he refers

to the way luctuations in the global economy, and decisions taken by the major

industrial nations, have sometimes caused serious problems for Indonesia. On the other hand, Widjojo is an internationalist, including in the matter of international borrowings. In addressing the parliament in November 1969, he discussed at length Indonesia’s ‘old debts and new debts’ (ch. 20). Faced with the challenge of

11 Among other projects, he mentions PT Krakatau Steel; LNG projects in Aceh; various fertiliser projects (including initiatives in Kalimantan and Cirebon, and others involving

the state-owned Pusri fertiliser company); oil reinery activities in Cilacap; and a major

persuading sceptical members of parliament to adopt a sensible foreign borrow-ing program, he tactfully surveyed the recent history of Indonesia’s international borrowings and set out the country’s needs for the future.

In discussing Indonesia’s experience, he explained that since 1966 the govern-ment had followed a cautious approach in negotiations with international creditors about debts due from the Soekarno era. He emphasised that the negotiations had

been dificult. The government had been seeking to minimise the debt burden, but

creditors had legitimate interests as well. His clear message to members of parlia-ment was that it was in Indonesia’s long-term interests to handle its international debt problems in a responsible way. Summarising the dilemma, Widjojo said:

When there is a change of government … such as occurred in our country in

mid-1966, then the matter of old debts and new debts becomes relevant. Old debts are those incurred by the previous government that have not been fully repaid. The repayment of old debts becomes a responsibility of the new government. If the new government is not prepared to accept responsibility for the old debts and refuses to acknowledge them as an ongoing commitment, then other governments will not be prepared to provide [it with] new loans and, moreover, will lay charges against [it]

in their own courts or in international courts. They may well coniscate property of

the new government, such as planes and ships that are in their territory. Because of these considerations, the only course of action for a new government is to acknowl-edge the debts of the previous administration and look for ways to settle them as well as possible. It is the responsibility of the new government to seek the best way forward and to prevent a repeat of the situation in the future (p. 395).

He then turned to the present. Weighing up the challenges Indonesia faced in 1969, Widjojo drew on the ‘gap analysis’ approach that was still widely used in the late 1960s, to suggest to the parliamentarians that Indonesia had an urgent need to obtain foreign resources. His conclusion after discussing both the external (balance of payments) and internal (budget) gaps was that:

Bearing all of this in mind, if we are realistic and don’t want to bury our heads in the sand, the need for international borrowings and foreign aid is clear, from the viewpoint of both the balance of payments and budgetary pressures (p. 407).

But then, in the next stage of his address to the parliament, he proceeded to tease out in subtle ways the central issues of foreign borrowing. Harking back to the Soekarno era, he posed the rhetorical question: ‘Is it not possible to replace for-eign borrowings by printing money?’ In putting this question, without directly

mentioning the dificulties that arose during the still-too-recent Soekarno era, he

raised key questions to which his audience surely wanted answers. He gave two:

irst, that the principal challenge for Indonesia was not so much inding money

as spending it well; and second, that Indonesia’s most urgent need at the time was for increased supplies of foreign, not domestic, resources – and that foreign resources could not be obtained by the printing of rupiah (p. 408).

Looking over this summary of Indonesia’s international debt management strategy today, 40 years after the approach was outlined to the parliament, one is struck by the care given to efforts to ensure that Indonesia’s new approach to the international community was understood and accepted. At the time, the new Soeharto government was just beginning to build its economic credentials both at home and abroad. Widjojo therefore needed to emphasise that the adventurous and experimental ways of the past would not be repeated, that Indonesia would meet all reasonable international commitments, and that it was keen to retain

access to international inancial markets both to meet urgent funding needs and

to support longer-term development programs. Indeed, much of the thrust of the strategy remains just as relevant now as it was 40 years ago, because Indonesia still

needs large amounts of capital to inance development. The case Widjojo made to the parliament in 1969 in support of international borrowings could proitably be

re-read by parliamentarians today.

The price mechanism

A sixth theme is the importance of prices, both in international markets and at home. Variations in international prices, especially of commodities such as oil, but

also of other tradable goods, foreign exchange and inancial capital, have often

had a dramatic impact on the Indonesian economy in recent decades. Important

episodes that Widjojo discusses in detail include the remarkable luctuations

in oil prices in the 1970s and 1980s; the associated movements in international exchange rates, including the ‘Nixon Shock’ of 1971 and the large international realignments between the Plaza and Louvre Accords of 1985 and 1987; and the marked changes in international interest rates and equity prices during the 1980s.

Large international price movements of this kind tend to low through to the

Indonesian economy quite quickly. Policy makers needed to be constantly ready to make adjustments to domestic policy in response.

On the controversial subject of domestic prices, Widjojo is generally somewhat more circumspect. Like many of his economist colleagues in Indonesia, he is inclined to focus on the macroeconomic implications of price changes rather than on the implications of price policy in particular markets and industries. He also shares (or, at least, judges it wise to allow for) the concerns that many policy mak-ers and commentators have about the problems that can arise from uncontrolled markets. At various times, for example, he warns of the exploitation that can arise

from ‘free-ight liberalism’, and the dificulties that sharp price changes in inter -national markets can give rise to within Indonesia.

But Widjojo is certainly alert to the importance of price policies for key markets at home – especially in the politically sensitive food (rice), fuel and utility sectors. He urges that policy makers be pragmatic in responding to exogenous changes from any quarter. And he adopts a pro-market approach, arguing that govern-ments need to be ready to adjust domestic pricing policies in key sectors such as rice and fuel when circumstances suggest that price changes would be helpful.

Indonesia and the world

The last of the main themes that recurs throughout the collection is Widjojo’s awareness of Indonesia’s place in the international community, and especially

Indonesia can gain from interacting with the global development community and to the ways it might in turn contribute to international understanding of the chal-lenges of global development.

Widjojo’s views on how Indonesia should interact with the international com-munity combine distinct elements of both nationalism and internationalism. As a nationalist, he is aware that the major nations of the world pay scant attention to the interests of developing countries like Indonesia when they negotiate among themselves over policies that affect the management of the global economy. Writ-ing in 1990 (‘Progress and challenges of Indonesia’s development’), he noted, quite simply and without rancour, that

… [w]hen the industrial countries take decisions about matters that have a global

impact, they fail to consider – or, at best, give little attention to – the implications for developing countries. The G-7 countries, and in recent events [concerning the Plaza and Louvre Accords in the period 1985–87] just the G-2 countries [the United States and Japan] alone, constantly leave developing countries on the periphery, well out of sight and mind (p. 192).

And earlier, at a conference in Tokyo in 1984, in a keynote speech on ‘Perceptions of interdependence but lack of meaningful actions’, Widjojo had been pointedly

critical of the commitment of rich countries in the ield of North–South coopera -tion. He declared that

[t]here has already been a plethora of global conferences – high-level conferences,

ministerial-level conferences and so on – that have set out irm commitments about things like international development cooperation, commitments to … foster open

trading arrangements, and commitments to better manage arrangements for multi-lateral economic cooperation. But unfortunately none of these international

eco-nomic conferences has managed to bring about any signiicant progress in the area

of international economic cooperation. And in fact, in all of the North–South forum

dialogue meetings that have been held, the inal results have led to dead ends, or

to efforts that have just faded away, or even to a weakening of earlier commitments that had been entered into (p. 539).

But despite this plain speaking in his nationalist role, Widjojo also has an internationalist’s perspective on Indonesia’s links with the world. While he constantly emphasises that conducting effective economic diplomacy and

operating in global markets is a dificult task requiring leaders and oficials to be

on guard, he also argues that it is clearly in Indonesia’s interests to interact closely with the global community.

Widjojo is an Indonesian nationalist in another sense too. Like his other

colleagues in the Berkeley Maia, he has been glad to be able to point to Indonesia’s

During these efforts at South–South cooperation and on other occasions, Widjojo was keen to share the lessons of Indonesia’s development programs with other emerging countries. He discussed Indonesia’s experience of family plan-ning, its programs in the agricultural sector to improve food production, and especially its efforts in the area of poverty alleviation. Key aspects of Indonesia’s anti-poverty programs that Widjojo highlighted were a strong emphasis on rural development; sustained economic reform, including a budget policy that focused on anti-poverty programs; and pro-market deregulatory and pricing policies designed to promote economic growth through labour-intensive activities in agri-culture and manufacturing. According to Widjojo,

… it is the rapid growth of sustainable, labour-intensive industry that has been the

most important factor in reducing poverty in Indonesia. The close relationship

be-tween this growth and reductions in the number of poor can be seen in the speciic

type of growth that has occurred in Indonesia: rapid growth in the agricultural sec-tor followed by rapid growth in labour-intensive manufacturing – accompanied by policy packages that have supported growth in these sectors (p. 485).

WIDJOJO’S KEY MESSAGES

Widjojo’s is the voice of one of the developing world’s most eminent policy mak-ers in the latter part of the 20th century. What, then, are the central emphases that

emerge from his writings over 30 years of development policy making? Perhaps three stand out: growth, leadership and stability.

First, Widjojo is in no doubt about the need for strong and sustained economic growth to overcome poverty and promote development. He favours high levels of

sound public and private investment, effective iscal policies, continual economic

reform, and clear sectoral policies – all because they underpin strong economic growth. Interestingly, this collection of articles written up to 1997 says little about one of the headline issues in the debate on growth and development today – climate

change. Doubtless his well-known colleague Emil Salim has helped to ill this gap

in recent years. But it would be a mistake to overlook the view on energy consump-tion levels and internaconsump-tional environment issues that Widjojo set out in 1990:

Energy consumption per capita in Indonesia is very low, and indeed rather low even when compared with the level in some other countries in Asia. Indonesia has natural energy resources such as oil, coal and hydro-power. If industrial countries try to prevent the use of these resources for Indonesia’s development without giv-ing attention to practical alternatives, while they themselves maintain extravagant standards of living that use up much oil and coal, then this must be seen as an at-tempt on their part to constrain Indonesia’s development. Because of this, more ef-forts are needed by industrial countries to curb environmental damage within their own borders and, at the same time, to become more willing to support programs that promote sustainable development in emerging countries. (p. 196).

The relatively slight attention that Widjojo gives to environmental issues in

these essays may relect the priorities of the period when he was a policy maker. But what is just as likely is that it relects the quite different priorities that rich

Second, Widjojo has clear views about some key matters now regarded in inter-national development circles as leadership and governance questions. He speaks strongly of the need for effective leadership and (not necessarily quite the same thing) for good, sensible management in developing countries. Policy makers in rich countries who have for years delivered lectures about the need for develop-ing countries to take more responsibility for their own progress may welcome these views with enthusiasm. And there is a strong message in Widjojo’s empha-sis on the need for economic policy leadership that reempha-sists vested interests.

But there are some implications of the approach he outlines that leaders in rich

countries might not quickly notice – including the possibility that as the conidence

of developing country leaders grows, the views they express may increasingly diverge from the dominant perspectives in the rich world. India, for example, had

a irm position on trade policy issues that contributed to the failure to conclude

an agreement during the Doha round of trade negotiations in 2008. And more recently, China’s concern to protect its interests complicated efforts to reach agree-ment during the 2009 Copenhagen negotiations on global environagree-mental policy. In these, and in other matters, as the strength of leadership in emerging countries grows, differences in the interests of rich and poor countries can be expected to become more evident.

Third, throughout this collection, Widjojo constantly returns to policy issues linked to risk and stability. This is surely understandable. Both internal and exter-nal instability have been an important part of the story of Indonesian economic development in recent decades. Policy makers such as Widjojo have needed con-stantly to adjust economic policy to respond to shocks.

Indeed, by the standards of most rich countries, Widjojo and his colleagues have had to face a remarkable degree of instability in setting economic policy. Some challenges, such as the Pertamina crisis of 1975 and other poor investments in the state-owned enterprise sector, were largely the result of domestic mistakes. In other cases, the economic shocks were exogenous, caused by unexpected events overseas. But for Widjojo, the source of the shocks is far less important than the need for policy makers to be cautious and alert all of the time, and to respond quickly and in an economically responsible way to such shocks when they occur.

BEYOND THE COLLECTION

Some readers of Pengalaman Pembangunan Indonesia will be struck – and perhaps disappointed – by the fact that the collection ends in 1997, almost as a bookend

to the Soeharto era. Widjojo says nothing either about the economic dificulties

that emerged so rapidly in the latter half of 1997 in Indonesia or about the Asian

inancial crisis of 1998–99. But it is unlikely that he would have been surprised by

what happened. For 30 years he had been emphasising the need for policy makers to be ready to respond to unexpected shocks. And so it was, at the end of his career as a close adviser to President Soeharto, that the importance of this key message was illustrated by the dramatic turn of events as the Asian crisis broke out. In a visit I paid to Widjojo in mid-1996 he mentioned, in a way that was very striking at the time, his concerns about the future. I had just attended an international meeting in Tokyo to review economic developments in Cambodia. After we had discussed the

can happen again in Indonesia too. People forget. … Our economic progress is still

fragile. If we make mistakes, we can lose many of the gains quite quickly.’ By the end of the following year, it was clear that he was right.

Another subject about which Widjojo says nothing throughout the entire col-lection is the nature of his relationship with Soeharto. It is clear that it was a long and close relationship and that the president both listened to and trusted him. But how was it possible for Widjojo to establish and maintain such an effective rela-tionship? The two men came from extremely different backgrounds. Widjojo was a middle-class university professor, a civilian who had been privileged enough to gain a doctoral degree from an American university. Soeharto had grown up in poverty-stricken circumstances in rural Java, had had but a sparse education, had spent all of his professional years in the rough world of the Indonesian military of the 1950s and 1960s, and had virtually no personal experience of the international sphere (Dwipayana and Ramadhan 1989; Elson 2001).

Part of the answer, perhaps, is that Widjojo and his Berkeley Maia colleagues were able to win the conidence of Soeharto and other senior military igures

during the early 1960s, and especially in 1966, during the crucial transition from Soekarno’s ‘Old Order’ to Soeharto’s ‘New Order’.12 The discussions that took

place during an army seminar in Bandung in August 1966 are widely reported to have been ‘of crucial importance to the intellectual content and program of what was to become the New Order’ (Elson 2001: 148). At that seminar, Widjojo and his

colleagues worked closely with inluential military leaders to prepare the broad

outlines of an economic and social program for Indonesia in the post-Soekarno era.13

But perhaps the main answer to the question of how it was possible for Widjojo to build such an effective personal relationship with Soeharto is to be found, par-adoxically, in his silence on the subject in the pages of the collection. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of Widjojo’s friends and colleagues encouraged him over the years to talk more openly of his relationship with Soeharto. Yet he has always strictly protected his trusted association with the former president, even after Soe-harto’s resignation in 1998, and indeed even after his death a decade later. And there may be the answer: Widjojo and Soeharto were Javanese politicians and statesmen, one an adviser and one a ruler, who had a close understanding of their

relationship. They were able to forge an alliance that was to their mutual beneit and to the great beneit of the nation. One of the essential conditions for its success

was mutual respect and silence – and that is why there is no discussion of the relationship in Widjojo’s collection.

12 Sadli discusses the growing links between economists from the University of Indo-nesia and senior military leaders in the late 1950s and 1960s (Sadli 2003: 125–8). Prawiro (1998: 84) observes that it was ‘highly fortuitous’ that these economists became known and respected by the military leadership, including Soeharto, during the early 1960s.

CONCLUSION

The central messages that Widjojo sets out in the collection are simple ones. But

they are also profound. And the fundamental emphasis that the Berkeley Maia

technocrats placed on sound economic policy has established a tradition in senior Indonesian policy-making circles that has endured to the present day. Fortunate

indeed is a country that inds advisers such as Widjojo and his colleagues from within, irst, to guide a recovery from dificult times, and then to provide irm

direction in economic policy for decades to come.

REFERENCES

Arsjad Anwar, M., Thee Kian Wie and Azis, Iwan Jaya (eds) (1992) Pemikiran, Pelaksanaan dan Perintisan Pembangunan Ekonomi [Thinking, Implementation and Pioneering in Eco-nomic Development], Faculty of EcoEco-nomics, University of Indonesia, and PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama, Jakarta.

Arsjad Anwar, M., Ananta, Aris and Kuncoro, Ari (eds) (2007a) Kesan Para Sahabat tentang Widjojo Nitisastro [Friends’ Impressions of Widjojo Nitisastro], also published as Testi-monials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro (2008), Kompas Book Publishing, Jakarta. Arsjad Anwar, M., Ananta, Aris and Kuncoro, Ari (eds) (2007b) Tributes for Widjojo

Niti-sastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries, Kompas Book Publishing, Jakarta.

Elson, R.E. (2001) Suharto: A Political Biography, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Esmara, Hendra (ed.) (1987) Teori Ekonomi dan Kebijaksanaan Pembangunan: Kumpulan Esei

untuk Menghormati Sumitro Djojohadikusumo [Economic Theory and Development Pol-icy: A Collection of Essays in Honour of Sumitro Djojohadikusumo], PT Gramedia, Jakarta.

Mackie, J.A.C. (1970) ‘The Report of the Commission of Four on Corruption’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 6 (3): 87–101.

McCawley, Peter and colleagues (2002) ‘Heinz Arndt: an appreciation’, Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 38 (2): 163–76.

Nitisastro, Widjojo (1970) Population Trends in Indonesia, Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY.

Nitisastro, Widjojo (2010) Pengalaman Pembangunan Indonesia: Kumpulan Tulisan dan Uraian Widjojo Nitisastro [The Experience of Development in Indonesia: A Collection of the Writings of Widjojo Nitisastro], Penerbit Buku Kompas, Jakarta.

Prawiro, Radius (1998) Indonesia’s Struggle for Economic Development: Pragmatism in Action, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Sadli, Mohammad (2003) ‘Mohammad Sadli’, in Recollections: The Indonesian Economy, 1950s–1990s, ed. Thee Kian Wie, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 119–39. Salim, Emil (2003) ‘Emil Salim’, in Recollections: The Indonesian Economy, 1950s–1990s, ed.

Thee Kian Wie, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 185–219.

Dwipayana, G. and Ramadhan, K.H. (1989) Soeharto, Pikiran, Ucapan dan Tindakan Saya: Otobiograi [Soeharto, My Thoughts, Words and Deeds: An Autobiography], PT Citra Lamtoro Gung Persada, Jakarta.

Thee Kian Wie (2002) ‘The Soeharto era and after: stability, development and crisis, 1966– 2000’, in The Emergence of a National Economy: An Economic History of Indonesia 1800–2000, Howard Dick, Vincent J.H. Houben, J. Thomas Lindblad and Thee Kian Wie, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, and University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu: 194–243.