Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:25

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Predicting MBA Student Success and Streamlining

the Admissions Process

William R. Pratt

To cite this article: William R. Pratt (2015) Predicting MBA Student Success and

Streamlining the Admissions Process, Journal of Education for Business, 90:5, 247-254, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1027164

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1027164

Published online: 23 Apr 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 77

View related articles

Predicting MBA Student Success and Streamlining

the Admissions Process

William R. Pratt

Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania, USA

Within this study the author examines factors commonly employed as master of business administration applicant evaluation criteria to see if these criteria are important in determining an applicant’s potential for success. The findings indicate that the Graduate Management Admissions Test (GMAT) is not a significant predictor of student success when considering factors such as undergraduate grade point average and work experience. Furthermore, the results suggest that prior findings in support of the GMAT are the result of missing variables in the model specification. Our results show that undergraduate grade point average alone can be employed as an admission criterion and indicator of potential success in lieu of the GMAT; adopting this criterion instead can streamline the admission process while minimizing student expenses. Within the discussion section the author offers suggestions for reducing the need for the GMAT score information in the admissions process.

Keywords: admission criteria, GMAT, MBA, waiver

Traditionally, the approach employed to assess a busi-ness graduate school applicant involves an official Grad-uate Management Admissions Test (GMAT) score(s), undergraduate transcript, resume, letters of recommenda-tion, and a personal essay(s). The GMAT is a standard-ized exam that is widely used by more than 6,000 management programs worldwide (Graduate Manage-ment Admission Council, 2014). The purpose of the GMAT is to provide business schools with a standard-ized metric of comparison that other metrics do not pos-sess. However, over the past 25C years the GMAT has received much criticism and contention such as: claims of incorrect score reporting over a 10-month period, wide scale cheating, low explanation of student out-comes, and that the GMAT disadvantages minority stu-dents (Dowling, 2009; Fairtest, 2001, 2008; Gropper, 2007; Hechinger, 2008; Tanguma, Serviere-Munoz, & Gonzalez, 2012). Given such reports, it is important to ask is the GMAT a necessary admissions criterion? Within this study I explore this question and to identify possible alternatives for the admissions process.

The prior research employs explanatory variables such as the GMAT scores and undergraduate grade point average (UGPA) in investigation of which measures are linked to student success. The results from these studies are mixed in findings of significance, the covariates employed, and the response variable(s) used to measure of success. In addi-tion, the majority of studies have not identified or recom-mended criteria in lieu of the GMAT, and the purpose of this study is to see if a viable alternative(s) exists.

The empirical findings of this study indicate that the GMAT is not a consistent significant predictor of student graduation, whereas UGPA and work experience offer information on the probability of student outcomes. I find that years of work experience will tend to result in a lower probability of graduation, consistent with the prior report of Gropper (2007), who noted a negative relationship between work experience and overall master of business administra-tion (MBA) performance. Specifically, I note a nonlinear relationship between work experience and student graduation.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. In the next section I provide a review of the extant literature, followed by hypotheses to be tested. The next section describes the data and methodology employed. I finish with a presentation of the results with a discussion of limitations and a conclusion.

Correspondence should be addressed to William R. Pratt, Clarion Uni-versity of Pennsylvania, Department of Finance, 840 Wood Street, Still Hall, Office 325, Clarion, PA 16214, USA. E-mail: williamrpratt@gmail. com

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1027164

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Admissions Criteria

Typically most graduate schools and researchers employ admissions criteria such as the GMAT, undergraduate GPA, work experience, and age as predictors of perfor-mance in MBA programs. Some research suggests addi-tional explanatory factors such as gender, undergraduate field of study, and time since graduation, with some linking outcomes to the type of program enrollment (traditional, executive MBA [EMBA], online, 11-month).

Studies employing the GMAT can be categorized as either tests of significance where the GMAT is a predictor of student outcomes or as an analysis of variance explained. In studies examining the GMAT, the results are widely mixed. The literature appears to be equally divided on the GMAT as a predictor of student success, with varying defi-nitions of success. For instance, Gropper (2007) found that the GMAT can explain first-year MBA student GPA, how-ever with respect to overall program performance the GMAT lacks statistical significance. Supporting Gropper’s findings, a number of studies report significance with first year performance (Kuncel, Crede, & Thomas, 2005, 2007). A common finding of predictor studies points to the GMAT being an important factor, but less than factors such as UGPA (Borde, 2007; Fairfield-Sonn, Kolluri, Singamsetti, & Wahab, 2010; Sulaiman & Mohezar, 2006; Yang & Lu, 2001). Related in finding, Ahmadi, Raiszadeh, and Helms (1997) examined the variance explained by multiple predic-tors, noting that UGPA accounts for 27% of outcome vari-ance and 18% for the GMAT—comparable findings are observed in other studies (Paolillo, 1982; Truell, Zhao, Alexander, & Hill, 2006). Among others, Arnold et al. (1996) and Seigert (2008) suggested that both the GMAT and UGPA should be employed when assessing graduate applicants.

Contrary to the prior, a number of studies report that other factors are more important than UGPA or GMAT and often note that one or both lack statistical significance (Christensen, Nance, & White, 2011; Fish & Wilson, 2009). Adams and Hancock (2000) reported that amount of work experience is most related to student success relative to other predictors. Researchers have suggested that work experience may also proxy for age or time since undergraduate studies. A study funded by the Graduate Management Admission Council suggested that time has a decay effect on the ability of UGPA to explain MBA success, such that the GMAT becomes a valuable indicator for assessing those who have been away from school for a number of years (Talento-Miller & Guo, 2009)—similar findings are reported by Peiperl and Tre-velyan (1997). Braunstein (2006) noted that work experience is a better predictor for students whose undergraduate degree is not business related. From these reports, I can expect to find

either a positive and negative relationship associated with work experience, and an undergraduate discipline-dependent relationship.

Similar to Braunstien (2006), a sizeable amount of research identifies the type of undergraduate degree as a potential predictor of success in a MBA program. Sulaiman and Mohezar (2006) found that undergraduate discipline is a predictor of MBA success. Moses (1987) also found that accounting majors are more likely to be successful in cer-tain coursework due to their exposure to frequent reading of business publications and accounting knowledge. Simi-larly, Christensen et al. (2011) found support for account-ing as a significant determinant, though only at the 10% level; however, they do identify performance in undergrad-uate economics and statistics as statistically significant determinants of success. Gropper (2007) offered similar evidence of undergraduate degree type lending to success in a MBA program.

MBA Programs

With advances in technology and an increasing demand for management training, business schools often offer multiple methods of instruction to meet the needs of working professionals. Differing from the traditional two-year face-to-face MBA, students may pursue a MBA in a part-time, online, or executive track setting. It is important to note that students choose their specific program track, hence method of instruction may be linked to student characteristics. Hobbs and Gropper (2013) identified that the characteristics of students entering into an EMBA differ from students entering into the traditional face-to-face program—typically an EMBA requires a minimum of five years of work expe-rience. Guy and Lownes-Jackson (2013) noted that face-to-face students typically have better pre-and postin-struction test results in assessment of a single MBA course. Davis (2014) noted a similar difference in stu-dent performance in online versus traditional. Edward (2006) suggested the difference is a result of condensing the traditional two-year program to into intensive for-mats with new methods of content delivery and struc-ture. As the program types vary, it is not surprising that predictors vary by program type (Carver & King, 1994; Fish & Wilson, 2009; Siegert, 2008). However, Taher et al. (2011) suggested that differences in success are the result individual personality type and learning approaches. Their report suggests that it is necessary to allow for variation by program type.

HYPOTHESES

The functional role of the admissions process is to assess applicants’ potential for success and fit. Understandably the

248 W. R. PRATT

result of the admissions process will have a significant impact on an applicant’s future and incorporating poor cri-terion could have a negative impact on the applicant’s future. Considering the significant impact the admissions process will have on an applicant’s future, it is necessary to ensure that the admission criterion correctly serve as an information source of success. A summary of our hypothe-ses is the following:

Hypothesis 1(H1):The GMAT is a positive predictor

of MBA student success.

H2: Undergraduate GPA is a positive predictor of

MBA student success.

H3: Work experience is positive predictor of MBA

student success.

H4: Having an undergraduate business degree would

increase the likelihood of success.

The first research question is, is the GMAT a predictor of MBA student success? Within the extant literature the reports are widely mixed. In Kuncel et al. (2005, 2007) and Siegert (2008) reported that the GMAT is a significant and important predictor of a student’s potential, whereas Adams and Hancock (2000) and Christensen (2011) did not find such a relationship. PerH1, I expect to find a positive

rela-tionship between GMAT and graduation, such that the probability of graduating will increase with an increase in GMAT score.

Our second research question is interested in the quality of the information conveyed in undergraduate GPA—is undergraduate GPA a predictor of MBA student success? Similar to H1, the literature is mixed in findings, either

identifying UGPA as positively related (Borde, 2007), or, similar to Seigert (2008), failing to find statistical signifi-cance—I am not aware of any studies that report an inverse (negative) relationship between UGPA and graduating (Christensen et al., 2011; Fish & Wilson, 2009). PerH2, I

expect UGPA to be positively related to graduation, such that the probability of graduating will increase with an increase in UGPA.

ForH3, I state that work experience is a positive

predic-tor of MBA success. As in the report of Adams and Han-cock (2000), I expect to find that work experience is a predictor of MBA success, such that an increase in work experience will lend to a greater probability of success.

I also examine the ability of students having an undergraduate degree in business versus students that do not. Consistent with the prior reports of Braunstien (2006), Sulaiman and Mohezar (2006), and Christensen et al. (2011), I expect to find that having an undergradu-ate business degree will increase the likelihood of suc-cess—H4.

DATA

The analysis employs data on 271 business graduate stu-dents that attended an Association to Advance Colle-giate Schools of Business–accredited MBA program. The data employed include information on the students’ undergraduate major, UGPA, graduate GPA, years of professional work experience, the program track the stu-dent applied for (traditional, 11-month program, EMBA, or online), indication if the student was suspended from the program, and GMAT score if available. The pro-gram employs a requirement of foundation coursework that is designed to ensure students have a foundation knowledge before attempting coursework from the MBA core classes. The foundation coursework is usually ful-filled by an undergraduate degree in business; therefore foundation coursework is usually typically only required of students who do not have an undergraduate degree in business.

During the data collection period, the program employed a policy of case-by-case GMAT waiver, so the sample includes GMAT scores for 170 students.1Hence 101 stu-dents were admitted without GMAT scores. Within the analysis I use the sample of 170 students who have GMAT scores to attain the regression estimates, I later employ the larger sample of 271 students to predict the probability of graduating using only UGPA.

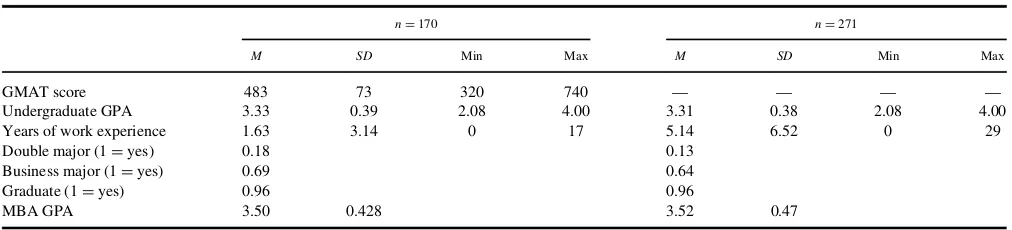

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics. The total sam-ple employed is 271, with 170 having GMAT data. The sample GMAT scores range from 320 to 740 with a mean of 483. In terms of percentiles of all GMAT test takers, the sample ranges from the fifth percentile to the 97th and the mean of the GMAT score is approximately the 27th percentile of all test takers. Undergraduate GPAs range from a low of 2.08 to 4.00, the average UGPA entering into the program is 3.33. Work experience ranges from zero to 29 years—98 of the 271 individuals reported they had no professional work experience. The second quartile includes 38 observations that have one or two years of work experience. The third quartile spans from three to seven years and the fourth quartile spans from eight to 29 years. Thirteen percent of all students (ND271) enter-ing into the graduate program report haventer-ing double maj-ored in their undergraduate studies.

The response variable graduate indicates if a student successfully completed the MBA program. The value of .96 indicates that 4% of the sample was unsuccessful in the MBA program. The statistic MBA GPA indicates the per-formance in the 10 core courses of the program—the sam-ple of students who took the GMAT have a mean MBA

GPA of 3.50 and the mean GPA increases to 3.52 when the pool receiving waivers is added to the main sample.

RESEARCH METHOD

Prior findings indicate that the type of MBA program may affect the student’s likelihood of success. To account for this effect, I employed a multilevel model with a random intercept for program type (traditional, EMBA, online, 11-month). The response variableyij[GraduateD1] uses logit

as the link function. With student-level covariates xi and

zetajaccounting for the type of MBA program:

Logit[

Prob

.

y

ijD

1

j

x

ij;

z

Using Stata 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX), I employed the GLLAMM command, which maximizes the log likelihood via Newton’s method to attain the estimates presented in the Results section—refer to Rabe-Hesketh and Scrondal (2003, 2008) for a more in-depth discussion.

Assessing the Link Function

Prior research has identified potential bias in logistic regres-sion when examining rare events. Typically the rare occur-rence is observed less than 1% of the time. I assess the link function by comparing the descriptive statistics of the sam-ple with predicted values that are attained from the regres-sion. If the link function is correctly specified, then I expect the predicted probability of success to be similar to that of the sample 96%—refer to the descriptive statistics in Table 1.

I find that the predicted probabilities using logit as con-sistent with the sample. The predicted probability of suc-cess differs from the actual sample by only .3% (.96 sample

vs. .963 predicted) and when employing the probit link the probability of success is 86%, 10% lower than observed in the sample. In addition, the probit estimates were found to have the same coefficient sign and similar levels of sig-nificance, such that the information is consistent—as expected the logit and probit differ in the fitted tail values as a result of the respective cumulative distribution function (CDF).

I also perform 100,000 simulations using the Stata com-mand GLLASIM. The simulation output employing the logit link results in a mean estimate of .9631 (s D.0005) for the intercept only model and .9631 (s D.0171) when undergraduate GPA is employed. I identify logit as the link function that better represents the data.

RESULTS

The results of our analysis are presented in Tables 2 and 3. In Tables 2 and 3, columns 1–4 examine predictors without employing GMAT scores. Columns 5–9 examine predictor with the use of GMAT scores. Table 2 reports the estimates for the sample of students who have GMAT scores (n D 170). The total sample of students consists of two groups of students, either those that have a GMAT waiver (n D101) or those that having GMAT scores (ND170), resulting in a total sample size of 271 students. Table 2 esti-mates differ from the prior table in for columns 1–4N D

271, as GMAT scores are not employed and columns 5–9n

D 170, since GMAT scores are utilized—note that the reported values in columns 5–8 are identical in Tables 2 and 3.

Column 1 of Tables 2 and 3 employs no covariates, therefore the intercept value is the mean or average expected probability of graduating for the sample once the coefficient is exponentiated and converted into a probabil-ity. In columns 2–7, UGPA is a significant predictor of stu-dent success at the 95% level or better in support ofH2—I

reject the null hypothesis.

The covariates work experience and work experience squared are reported in columns 3–6. Each predictor is

TABLE 1 Descriptive Statistics

nD170 nD271

M SD Min Max M SD Min Max

GMAT score 483 73 320 740 — — — —

Undergraduate GPA 3.33 0.39 2.08 4.00 3.31 0.38 2.08 4.00

Years of work experience 1.63 3.14 0 17 5.14 6.52 0 29

Double major (1Dyes) 0.18 0.13

Business major (1Dyes) 0.69 0.64

Graduate (1Dyes) 0.96 0.96

MBA GPA 3.50 0.428 3.52 0.47

Note:GMATDGraduate Management Admissions Test; GPADgrade point average; MBADmaster of business administration.

250 W. R. PRATT

TABLE 2

Regression Estimates for Response Variable (Is Graduate [1Dyes, 0Dno])

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9)

Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR

Constant 3.496 (0.158)***

¡1.504 (1.347) ¡1.335 (2.591) ¡1.956 (4.029) ¡8.130 (2.052)***

¡7.585 (1.651)***

¡4.028 (1.907)*

¡4.326 (2.529) ¡1.496 (1.190) UGPA 1.557 (0.389)** 4.745

1.755 (0.610)** 5.783

1.992 (0.870)* 7.330

2.119 (0.153)*** 8.326

1.932 (0.185)*** 6.905

1.115 (0.427)** 3.050

1.200 (0.472)* 3.320

Work experience ¡0.842 (0.079)*** 0.431

¡0.953 (0.082)*** 0.386

¡1.062 (0.237)*** 0.346

¡0.952 (0.268)*** 0.386

¡0.019 (0.081) 0.981 Work experience2

0.086 (0.029)** 1.090

0.099 (0.025)*** 1.104

0.106 (0.008)*** 1.112

0.094 (0.007)*** 1.099

Business major 0.293 (1.303) 1.340 0.180 (1.113) 1.197 Double major ¡1.067 (0.551) 0.344 ¡0.949 (0.423)* 0.387

GMAT score 0.013 (0.009) 1.013 0.013 (0.007) 1.013 0.009 (0.003)** 1.009

0.009 (0.003)** 1.009

0.011 (0.002)*** 1.011

Enroll 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) Log likelihood ¡22.558 ¡21.598 ¡19.588 ¡19.238 ¡18.010 ¡18.275 ¡20.797 ¡20.808 ¡21.307

Note: nD170. Robust standard errors are Huber/White. Columns 1–4 report coefficient estimates that do not employ GMAT scores. Columns 5–9 report coefficient estimates that do employ GMAT scores. GMATDGraduate Management Admissions Test; ORDodds ratio; UGPADundergraduate grade point average.

*p.05, **p.01, ***p.001.

TABLE 3

Regression Estimates With Full Sample (ND271)—Response Variable Is Graduate (1Dyes, 0Dno)

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9)

Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR Coefficient OR

Constant 3.262 (0.224)*** ¡0.663 (1.161) 0.6123 (2.121) 0.6223998 (2.363) ¡8.130 (2.052)*** ¡7.585 (1.651)*** ¡4.028 (1.907)* ¡4.326 (2.529) ¡1.496 (1.190) UGPA 1.218 (0.385)** 3.379 1.091 (0.445)* 2.978 1.072 (0.403)** 2.922 2.119 (0.153)*** 8.326 1.932 (0.185)*** 6.905 1.115 (0.427)** 3.050 1.200 (0.472)* 3.320

Work experience ¡0.465 (157)** 0.628 ¡0.476 (0.163)** 0.621 ¡1.062 (0.237)*** 0.346 ¡0.952 (0.268)*** 0.386 ¡0.019 (0.081) 0.981 Work experience2

0.031 1.031 (0.006)*** 0.031 1.032 (0.005)*** 0.106 1.112 (0.008)*** 0.094 1.099 (0.007)*** Business major 0.380 (0.646) 1.462 0.180 (1.113) 1.197

Double major ¡0.872 0.418 (0.082)*** ¡0.949 0.387 (0.423)*

GMAT score 0.013 (0.009) 1.013 0.013 (0.007) 1.013 0.009 (0.003)** 1.009 0.009 (0.003)** 1.009 0.011 (0.002)*** 1.011 Enroll 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000) 0.000 (0.000)

n 271 271 271 271 170 170 170 170 170

Log likelihood ¡42.809 ¡41.767 ¡38.679 ¡38.093 ¡18.010 ¡18.275 ¡20.797 ¡20.808 ¡21.307

Note: nD170. Robust standard errors are Huber/White. Columns 1–4 report coefficient estimates that do not employ GMAT scores—these values are attained using the larger data set ofND271.. Columns 5–9 report coefficient estimates that do employ GMAT scores— hence the sample size is limited tonD170. GMATDGraduate Management Admissions Test; ORDodds ratio; UGPADundergraduate grade point average.

*p.05, **p.01, ***p.001.

significant at the 99th percent level or better, though not in support ofH3—I am unable reject the null hypothesis.

Dif-fering from prior reports, I observe that in general work experience has a negative influence on a student’s probabil-ity of success, though the impact of the negative effect decreases with time as seen in the predictor work experi-ence squared. These findings potentially counter Talento-Miller and Guo’s (2009) report of a decay effect in the application of undergraduate grades as a predictor of stu-dent success. If I consider work experience as a proxy for the amount of time since graduation, then I can identify why a negative sign was observed—that is, perhaps the quality of information supplied by undergraduate GPA depreciates with time. Of course, if information deprecia-tion is occurring I would expect the UGPA to capture this effect, as well, I should observe a significant interaction between work experience and UGPA, and I do not. Instead there are other reasonable explanations such as the respon-sibilities of life increase after college graduation, coincid-ing with work experience or disconnects between theory and practical experience. Again, I tested for variable inter-action and did not find a significant relationship or a change in other covariates sign or level of significance. It is also worthy to note that squaring the work experience covariate is statistically important and I did not observe this approach in prior studies; however, it is probable that a prior study has applied this approach. I discuss work experience in col-umn seven when addressing the results of the predictor GMAT score.

The indicator variables business major (students having an undergraduate business degree D1) and double major (double majored in undergraduate studiesD1) are reported in columns 4 and 5. Having an undergraduate business degree does not appear to convey any useful information at the standard level, hence the results do not supportH4—I

am unable reject the null hypothesis. This finding also sug-gests that leveling courses do serve their purpose. Double major is significant at the 90th percentile in column 4 and at the 95th percentile in column 5. The only notable differ-ence between Tables 2 and 3 is observed in the variable double major where significance is greater in column four of Table 3. Unexpectedly, students that double majored have a lower probability of success, I also test for interac-tions with other covariates and no statistical significance was observed.

Columns 5–9 report the estimates for when GMAT scores are incorporated. In columns 7–9 I find that GMAT scores are statistically significant; however, in columns 5 and 6 GMAT scores are no longer statistically significant. The results suggest that GMAT information is significant only when a model is misspecified—testing for misspecifi-cation is addressed in the next paragraph. The results pro-vide only partial support for H1—I am unable to

confidently reject the null hypothesis.

Testing for Misspecification

With the results pointing towards possible misspecification, I assess the possible specification error by regressing the linear predicted value and square of the predicted value on the response variable. If the model is correctly specified the predicted value will not be statistically significant when regressed on the response variable—that is, the test has a null hypothesis that the model is misspecified. As well, the squared value should not provide any useful information. The misspecification test was performed for the model esti-mated in columns 3 (UGPA, work experience) and 8 (UGPA, GMAT). The specification test for column 3 indi-cated that the model is not misspecified and that I do not have omitted variables; however, the same test model pre-sented in column 8 indicates that the model is misspecified and that there is at least one omitted variable.

In addition I compare the fit of the model estimated in column 3 (UGPA, work experience) with that of column 6 (UGPA, work experience, GMAT) via likelihood ratio test. The likelihood ratio test measures if the difference in model fit is statistically better when additional variables are employed. The test reveals that adding the GMAT does not statistically improve upon the model of column 3, chi-squared probabilityD.1057. A similar result is found when comparing the log likelihood of columns 2 and 8—again, the GMAT does not statistically improve the model fit: chi-squared probabilityD.2087.2

DISCUSSION OF STUDY LIMITATIONS

The study is chiefly limited by a sample that includes grad-uate students from a single university; therefore these find-ings may only be representative of this sample and may not apply to other institutions. This limitation provides an opportunity for further research. Researchers may be inter-ested in applying the analysis of this study to a data set of multiple universities. Additionally, other topics of interests could include variation across university characteristics such as accreditation, population, and system affiliation.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study expand on the extant literature by providing empirical evidence that the GMAT is not a consis-tent predictor of student success in a MBA program. The find-ings suggest that prior support for the GMAT may be attributable to an under specified model. Furthermore, this finding reveals that the GMAT is not a dependable predictor of student success, hence it is not a necessary requirement for evaluating MBA program applicants. Instead the results show that undergraduate GPA and work experience are more

252 W. R. PRATT

appropriate measures for evaluation given that these measures convey as much if not more information than the GMAT and adding the GMAT to these measures does not statistically improve prediction accuracy. Rather, I find that the GMAT only statistically improves on models I observe as having specification error. I fail to find evidence that having an undergraduate degree in a business or business-based disci-pline (e.g., accounting, finance, management) lends to statisti-cally significant improved probability of success. As well, I do not find evidence that predictors of success differ by the type of MBA program (traditional, 11-month program, EMBA, or online) an applicant pursues.

Again, as these findings indicate that GMAT scores are not a necessary source of information for evaluating applicants, therefore Admissions committees may want to reduce student financial expense and streamline their admissions process/cri-teria by identifying methods for reducing their need for the GMAT requirement. Streamlining the admissions process/ criteria maybe achieved by multiple methods, for example, (a) Estimating the historic probability(ies) of success in a pro-gram and then establishing criteria such as a minimum under-graduate GPA that predicts the desired probable level of success, or (b) If a program is targeting a minimum GMAT score, then a committee may want to identify the probability of success associated with the targeted GMAT score and then identify an equivalent probability of success based on other criteria (e.g., UGPA, work experience). To be specific the first method identifies an ideal probability of student success, say 95%. After identifying the target level of success, then ascer-tain the undergraduate GPA that is associated with a 95% probability of success. If I assume that candidates with 3.25 undergraduate GPA have a 95% probability of success, I can then say the target level of .95 is comparable to the UGPA of 3.25. With respect to the second method, assume there is University X that wants to target a minimum GMAT score of 620. Under this method X would identify the proba-bility of success given the 620 GMAT score and then identify criteria that are able to provide an equivalent probability of success.

NOTES

1 Twelve of the GMAT scores are converted Graduate Record Examination (GRE) scores—the analysis was assessed with and without the converted GRE scores and there was not a significant change in the data or results. None of the students having converted scores were unsuccessful in the program.

2 The likelihood chi-squared ratio is attained by sub-tracting the difference of the two models and multi-plying by two [LR Chi2(1 df) D 2*(–18.275 – –19.588)D2.616]. The chi-squared probability is cal-culated using the measured chi-squared ratio and the difference in degrees of freedom.

REFERENCES

Adams, A. J., & Hancock, T. (2000). Work experience as a predictor of MBA performance.College Student Journal,34, 211–216.

Ahmadi, M., Raiszadeh, F., & Helms, M. (1997). An examination of the admis-sion criteria for the MBA programs: A case study.Education,117(4), 540. Arnold, L. R., Chakravarty, A. K., & Balakrishnan, N. (1996). Applicant

evaluation in an executive MBA program. Journal of Education for Business,71, 277–283. doi:10.1080/08832323.1996.10116798 Borde, S. F. (2007). A better predictor of graduate student performance in

finance: Is it GPA or GMAT?Financial Decisions,19, 1–9.

Braunstein, A. W. (2006). MBA academic performance and type of under-graduate degree possessed.College Student Journal,40, 685–690. Carver, M. R., & King, T. E. (1994). An empirical investigation of the

MBA admission criteria for nontraditional programs.Journal of Educa-tion for Business,70, 95–98. doi:10.1080/08832323.1994.10117732 Christensen, D. G., Nance, W. R., & White, D. W. (2011). Academic

per-formance in MBA programs: Do prerequisites really matter?Journal of Education for Business,87, 42–47. doi:10.1080/08832323.2011.555790 Davis, C. V. (2014).A comparative study of factors related to student

performance in online and traditional face-to-face MBA courses that are quantitative and qualitative in nature. (PhD thesis). Capella Univer-sity. Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/36/03/3603530.html Dowling, B. (2009). Admission to the Master of Business Administration

program: An alternative for Savannah State University.American Jour-nal of Business Education,2(1), 31–36.

Edward, C. (2006, November 6). Inside INSEAD’s admissions.Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved from http://www.businessweek.com/stories/ 2006-11-06/inside-inseads-admissionsbusinessweek-business-news-stock-market-and-financial-advice

Fairfield-Sonn, J. W., Kolluri, B., Singamsetti, R., & Wahab, M. (2010). GMAT and other determinants of GPA in an MBA program.American Journal of Business Education,3(12), 77–86.

Fairtest. (2001).GMAT error hurts applicants—Test-takers not told of mis-take for 10 months. Retrieved from http://www.fairtest.org/gmat-error-hurts-applicants-test-takers-not-told-mistake-10-months

Fish, L. A., & Wilson, F. S. (2009). Predicting performance of MBA stu-dents: Comparing the part-time MBA program and the one-year pro-gram.College Student Journal,43(1), 145–160.

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2014).The GMAT exam turns 60. Retrieved from http://newscenter.gmac.com/news-center/gmat-60 Gropper, D. M. (2007). Does the GMAT matter for executive MBA

stu-dents? Some empirical evidence.Academy of Management Learning & Education,6, 206–216. doi:10.5465/amle.2007.25223459

Guy, R., & Lownes-Jackson, M. (2013). Web-based tutorials and tradi-tional face-to-face lectures: A comparative analysis of student perfor-mance. Issues in Informing Science & Information Technology, 10, 241–259.

Hechinger, J. (2008). Business schools try palm scans to finger cheats.The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/ SB121669545112672811

Hobbs, B. K., & Gropper, D. M. (2013). Human capital indicators and aca-demic success in executive MBA programs: A multi-program study. Journal of Executive Education,4, 43–54.

Kuncel, N. R., Crede, M., & Thomas, L. L. (2005). The validity of self-reported grade point averages, class ranks, and test scores: A meta-anal-ysis and review of the literature.Review of Educational Research,75, 63–82. doi:10.3102/00346543075001063

Kuncel, N. R., Crede, M., & Thomas, L. L. (2007). A meta-analysis of the predictive validity of the Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT) and undergraduate grade point average (UGPA) for graduate student academic performance.Academy of Management Learning & Education,6, 51–68. doi:10.5465/amle.2007.24401702

Moses, O. (1987). Factors explaining performance in graduate-level accounting.Issues in Accounting Education,2, 281–291.

Paolillo, J. G. (1982). The predictive validity of selected admissions varia-bles relative to grade point average earned in a master of business administration program.Educational and Psychological Measurement, 42, 1163–1167. doi:10.1177/001316448204200423

Peiperl, M. A., & Trevelyan, R. (1997). Predictors of performance at busi-ness school and beyond: Demographic factors and the contrast between individual and group outcomes.Journal of Management Development, 16, 354–367. doi:10.1108/02621719710174534

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2003). Some applications of general-ized linear latent and mixed models in epidemiology: Repeated meas-ures, measurement error and multilevel modeling.Norsk Epidemiologi, 13(2), 265–278.

Rabe-Hesketh, S., & Skrondal, A. (2008). Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Corp.

Siegert, K. O. (2008). Executive education: Predicting student success in executive MBA programs.Journal of Education for Business,83, 221– 226. doi:10.3200/joeb.83.4.221–226

Sulaiman, A., & Mohezar, S. (2006). Student success factors: Identifying key predictors. Journal of Education for Business, 81, 328–333. doi:10.3200/joeb.81.6.328–333

Taher, A. M. M. H., Chen, J., & Yao, W. (2011). Key predictors of creative MBA students’ performance personality type and learning approaches. Journal of Technology Management in China,6, 43–68. doi:10.1108/ 17468771111105659

Talento-Miller, E., & Guo, F. (2009).When are grades no longer valid? A look at the effect of time on the usefulness of previous grades. GMAC Research Reports. Retrieved from http://www.gmac.com/~/media/Files/ gmac/Research/validity-and-testing/RR0905_TimeGrades.pdf Tanguma, J. S., Serviere–Munoz, L., & Gonzalez, A. D. (2012). Let me in!

The predictive validity of graduate management admissions test and other variables in the admission system of Masters of Business Adminis-tration programmes. International Journal of Business and Systems Research,6(2), 209–223. doi:10.1504/ijbsr.2012.046356

Truell, A. D., Zhao, J. J., Alexander, M. W., & Hill, I. B. (2006). Predicting final student performance in a graduate business program: The MBA. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal,48, 144–152.

Yang, B., & Lu, D. R. (2001). Predicting academic performance in man-agement education: An empirical investigation of MBA success.Journal of Education for Business,77, 15–20. doi:10.1080/08832320109599665

254 W. R. PRATT