ABSTRACT

ABAA, GRATIANUS S. A. Lecturers’ English-Indonesian-Javanese Code-Switching in English Students’ Classrooms. Yogyakarta: Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters, Sanata Dharma University, 2016.

Language is the system of communication. In a verbal communication like, for example, in a conversation, the language users sometimes have an ability to speak more than one language. Due to that matter, the language users often switch the use of language from one to another. One example of code-switching involves three different languages, which are English, Indonesian, and Javanese, in the classroom instructions produced by lecturers. In teaching English as a foreign language, code-switching is one of the methods applied by the lecturers in the classroom. Code-switching is quite important to be applied in helping lecturers avoid the occurrence of misunderstanding with the students. Therefore, this switch of language is given a special concern in the study.

The focus of the study itself is to answer two main problems. The first is to identify the types of code-switching used by the lecturers in the classroom instructions when the teaching-learning process is underway. Moreover, the second is to identify the reasons why lecturers use code-switching.

There are two dominant approaches of code-switching used in this study. They are the structural approach and the sociolinguistic approach. The structural approach is applied to answer the first problem on types of code-switching, in which there are three types of them; tag-switching, intersentential switching, and intrasentential switching. Meanwhile, the sociolinguistic approach is applied to answer the second problem on reasons of code-switching, in which there are many possible reasons, such as assert power and declare solidarity. For data collection, the methods applied for collecting data were by using record and interview techniques. Furthermore, the data, which were in the form of oral expressions, were transcribed into written form. Thus, the data were prepared for the analysis.

ABSTRAK

ABAA, GRATIANUS S. A. Lecturers’ English-Indonesian-Javanese Code-Switching in English Students’ Classrooms. Yogyakarta: Program Studi Sastra Inggris, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Sanata Dharma, 2016.

Bahasa adalah sistem komunikasi. Dalam komunikasi verbal seperti, contoh, di dalam sebuah percakapan, pengguna bahasa terkadang memiliki kemampuan untuk berbicara lebih dari satu bahasa. Karena itu, pengguna bahasa sering mengalihkan penggunaan bahasa dari satu bahasa ke bahasa lainnya. Satu contoh alih kode melibatkan tiga bahasa berbeda, yaitu bahasa Inggris, bahasa Indonesia, dan bahasa Jawa, dalam instruksi kelas yang diberikan oleh pengajar. Dalam mengajar bahasa Inggris sebagai bahasa asing, alih kode merupakan salah satu metode yang diterapkan pengajar di dalam kelas. Alih kode cukup penting diterapkan dalam membantu pengajar mencegah terjadinya kesalahpahaman dengan pelajar. Karenanya, pengalihan bahasa ini diberikan perhatian khusus dalam studi.

Fokus dari studi ini sendiri adalah untuk menjawab dua masalah utama. Pertama adalah untuk mengidentifikasi tipe alih kode yang digunakan pengajar dalam instruksi dalam kelas ketika proses belajar-mengajar sedang berlangsung. Selain itu, kedua adalah untuk mengidentifikasi alasan mengapa pengajar menggunakan alih kode.

Terdapat dua pendekatan dominan alih kode yang digunakan dalam studi ini. Mereka adalah pendekatan struktural dan pendekatan sosiolinguistik. Pendekatan struktural diterapkan untuk menjawab masalah pertama mengenai tipe alih kode, di mana terdapat tiga tipe; tag-switching, intersentential switching, dan intrasentential switching. Sementara itu, pendekatan sosiolinguistik diterapkan untuk menjawab masalah kedua mengenai alasan alih kode, di mana terdapat banyak alasan yang memungkinkan, seperti menegaskan kekuasaan dan menyatakan solidaritas. Untuk pengumpulan data, metode yang diterapkan untuk mengumpulkan data adalah dengan menggunakan teknik rekam dan wawancara. Selanjutnya, data, yang berupa ekspresi lisan, diubah kedalam bentuk tulisan. Kemudian, data siap untuk analisis.

LECTURERS’ ENGLISH

-INDONESIAN-JAVANESE

CODE-SWITCHING IN

ENGLISH STUDENTS’

CLASSROOMS

AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra

in English Letters

By

GRATIANUS SILAS ANDERSON ABAA Student Number: 114214052

ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS

FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

ii

LECTURERS’ ENGLISH

-INDONESIAN-JAVANESE

CODE-SWITCHING IN ENGLISH STUDENTS’ CLASSROOMS

AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra

in English Letters

By

GRATIANUS SILAS ANDERSON ABAA Student Number: 114214052

ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS

FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

iii

A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis

LECTURERS’ ENGLISH

-INDONESIAN-JAVANESE

CODE-SWITCHING IN ENGLISH STUDENTS’ CLASSROOMS

By

GRATIANUS SILAS ANDERSON ABAA Student Number: 114214052

Approved by

Dr. B. Ria Lestari, M.S. September 5, 2016 Advisor

iv

A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis

LECTURERS’ ENGLISH

-INDONESIAN-JAVANESE

CODE-SWITCHING ENGLISH STUDENTS’ CLAS

SROOMS

By

GRATIANUS SILAS ANDERSON ABAA Student Number: 114214052

Defended before the Board of Examiners on September 26, 2016

and Declared Acceptable

BOARD OF EXAMINERS

Name Signature

Chairperson : Dr. F.X. Siswadi, M.A.

Secretary : A.B. Sri Mulyani, Ph. D.

Member 1 : Adventina Putranti, S.S., M.Hum.

Member 2 : Dr. B. Ria Lestari, M.S.

Member 3 : Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A.

Yogyakarta, September 30, 2016 Faculty of Letters Sanata Dharma University

Dean

v

STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY

I certify this undergraduate thesis contains no material which has been previously submitted for the award of any other degree at any university, and that, to the best of my knowledge, this undergraduate thesis contains no material previously written by any other person except where due reference is made in the text of the undergraduate thesis.

Yogyakarta, September 4, 2016

vi

LEMBAR PERNYATAAN PERSETUJUAN PUBLIKASI KARYA ILMIAH UNTUK KEPENTINGAN AKADEMIS

Yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini, saya mahasiswa Universitas Sanata Dharma Nama : Gratianus Silas Anderson Abaa

Nomor Mahasiswa : 114214052

Demi pengembangan ilmu pengetahuan, saya memberikan kepada perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma karya ilmiah saya yang berjudul

LECTURERS’ ENGLISH

-INDONESIAN-JAVANESE

CODE-SWITCHING IN ENGLISH STUDENTS’ CLASSROOMS

Beserta perangkat yang diperlukan (bila ada). Dengan demikian saya memberikan kepada Perpustakaan Universitas Sanata Dharma hak untuk menyimpan, mengalihkan dalam bentuk media lain, mengelolanya dalam bentuk pangkalan data, mendistribusikan secara terbatas, dan mempublikasiannya di internet atau media lain untuk kepentingan akademis tanpa perlu meminta ijin kepada saya maupun memberikan royalty kepada saya selama tetap mencantumkan nama saya sebagai penulis.

Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dengan sebenarnya.

Dibuat di Yogyakarta

Pada tanggal 4 September 2016

Yang menyatakan

viii

For my Beloved Parents

ix

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to express my gratitude to The Almighty God, Jesus Christ, for blessing me with wonderful people who have never been absent in helping me get through the process of this thesis writing. My deepest gratitude goes to my thesis advisor, Dr. B. Ria Lestari, M.S. for her patience and tolerance during the consultation time. I would also like to express my gratitude to Dr. Fr. B. Alip, M.Pd., M.A. as my Co-Thesis advisor, for his corrections and criticism for the improvements of this thesis.

My warm gratitude goes to my lovely parents. I would like to thank my mother for all her prayers for me and her financial support. I would like to thank my father for the company for the last couple of months. I would also like to thank my family in Jayapura and Timika for all their support.

I would like to express my gratitude to the members of Save Orang Utan (SOU); Stefiana, Aldo, Alex, Bertha, Yanzher, and Dimas, for their company in helping me get through the process of writing this thesis. I would also like to thank Syntax Error for the last couple of years.

My gratitude also goes to my schoolmates: Utty, Erick, Everd, and Indra, for sharing their ups and downs in the process of writing their theses. I would like to thank my neighbor, Yosua, for always asking when I will graduate that I got annoyed and angry, and felt the urge to finish this thesis. To Kaka Enda, I thank her for the enlightenment and the encouragement in preparing me for the thesis defense. I am sure there is an endless list of people to thank for, therefore, I would also like to thank everyone who happens to help me in this process but has not been mentioned in here.

Last but not least, I would like to thank Beasiswa Unggulan Dirjen DIKTI Kemdikbud 2011 for helping me out finish my study. I would also like to thank Library of Sanata Dharma for providing the books I need to finish this thesis. I would like to thank all of the lecturers and staff of English Letters Department, Sanata Dharma University, as well, for helping me through this learning process. To all of my humble classmates in Class B batch 2011, I would like to thank them very much for being part of my learning process. I am definitely going to miss all the fun and the quality time we spent in class together.

x

A.Types of Code-Switching in English Students’ Classrooms. 27 a. Tag-Switching ... 28

b. Intersentential Switching ... …. 32

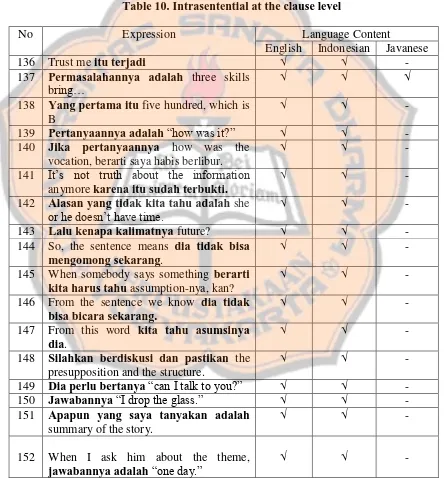

c. Intrasentential Switching ... 44

B. Reasons of Code-Switching in English Students’ Classrooms 57 CHAPTER V: CONCLUSION ... 62

BIBLIOGRAPHY ………. 64

xi ABSTRACT

ABAA, GRATIANUS S. A. Lecturers’ English-Indonesian-Javanese Code-Switching in English Students’ Classrooms. Yogyakarta: Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters, Sanata Dharma University, 2016.

Language is the system of communication. In a verbal communication like, for example, in a conversation, the language users sometimes have an ability to speak more than one language. Due to that matter, the language users often switch the use of language from one to another. One example of code-switching involves three different languages, which are English, Indonesian, and Javanese, in the classroom instructions produced by lecturers. In teaching English as a foreign language, code-switching is one of the methods applied by the lecturers in the classroom. Code-switching is quite important to be applied in helping lecturers avoid the occurrence of misunderstanding with the students. Therefore, this switch of language is given a special concern in the study.

The focus of the study itself is to answer two main problems. The first is to identify the types of code-switching used by the lecturers in the classroom instructions when the teaching-learning process is underway. Moreover, the second is to identify the reasons why lecturers use code-switching.

There are two dominant approaches of code-switching used in this study. They are the structural approach and the sociolinguistic approach. The structural approach is applied to answer the first problem on types of code-switching, in which there are three types of them; tag-switching, intersentential switching, and intrasentential switching. Meanwhile, the sociolinguistic approach is applied to answer the second problem on reasons of code-switching, in which there are many possible reasons, such as assert power and declare solidarity. For data collection, the methods applied for collecting data were by using record and interview techniques. Furthermore, the data, which were in the form of oral expressions, were transcribed into written form. Thus, the data were prepared for the analysis.

xii ABSTRAK

ABAA, GRATIANUS S. A. Lecturers’ English-Indonesian-Javanese Code-Switching in English Students’ Classrooms. Yogyakarta: Program Studi Sastra Inggris, Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Sanata Dharma, 2016.

Bahasa adalah sistem komunikasi. Dalam komunikasi verbal seperti, contoh, di dalam sebuah percakapan, pengguna bahasa terkadang memiliki kemampuan untuk berbicara lebih dari satu bahasa. Karena itu, pengguna bahasa sering mengalihkan penggunaan bahasa dari satu bahasa ke bahasa lainnya. Satu contoh alih kode melibatkan tiga bahasa berbeda, yaitu bahasa Inggris, bahasa Indonesia, dan bahasa Jawa, dalam instruksi kelas yang diberikan oleh pengajar. Dalam mengajar bahasa Inggris sebagai bahasa asing, alih kode merupakan salah satu metode yang diterapkan pengajar di dalam kelas. Alih kode cukup penting diterapkan dalam membantu pengajar mencegah terjadinya kesalahpahaman dengan pelajar. Karenanya, pengalihan bahasa ini diberikan perhatian khusus dalam studi.

Fokus dari studi ini sendiri adalah untuk menjawab dua masalah utama. Pertama adalah untuk mengidentifikasi tipe alih kode yang digunakan pengajar dalam instruksi dalam kelas ketika proses belajar-mengajar sedang berlangsung. Selain itu, kedua adalah untuk mengidentifikasi alasan mengapa pengajar menggunakan alih kode.

Terdapat dua pendekatan dominan alih kode yang digunakan dalam studi ini. Mereka adalah pendekatan struktural dan pendekatan sosiolinguistik. Pendekatan struktural diterapkan untuk menjawab masalah pertama mengenai tipe alih kode, di mana terdapat tiga tipe; tag-switching, intersentential switching, dan intrasentential switching. Sementara itu, pendekatan sosiolinguistik diterapkan untuk menjawab masalah kedua mengenai alasan alih kode, di mana terdapat banyak alasan yang memungkinkan, seperti menegaskan kekuasaan dan menyatakan solidaritas. Untuk pengumpulan data, metode yang diterapkan untuk mengumpulkan data adalah dengan menggunakan teknik rekam dan wawancara. Selanjutnya, data, yang berupa ekspresi lisan, diubah kedalam bentuk tulisan. Kemudian, data siap untuk analisis.

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

A. Background of the Study

Code-switching is a part of the study of the relation between language and society, called sociolinguistics. Code-switching concerns itself on the changing of language use from one to another in a single conversation. Wardhaugh (2006:101) mentions that “code” in code-switching refers to a particular dialect or language that

a person chooses to use in an occasion. Heller (1988:1) adds that code-switching occurs when a person mixes two languages in a single sentence or in a conversation. Therefore, according to the statement, it is concluded that code-switching is the process of switching language use from one to another occurring in a single conversation. One example of code-switching is the switch of language use from both English to Indonesian and English to Javanese. This switch of language is actually the topic that is going to be discussed in this study. This study discusses lecturers’ code

-switching in three different languages: English, Indonesian, and Javanese, in the classroom instructions.

Code-switching is often applied by the lecturers in the classroom to support students’ learning success. In teaching English as a foreign language, code-switching

misunderstandings in the classroom and the lecturers do not want to spend time giving detail explanations about the misunderstanding or searching for simplest words to clarify the misunderstanding and the confusion in the classroom, code-switching is applied to help the lecturers facilitating a good situation of teaching-learning process. In fact, lecturers apply code-switching as a means of providing opportunities towards the students and also enhancing students’ understanding

(Ahmad, 2009: 49). It is argued by Lai (1996: 91) that code-switching is needed to be a useful tool in assisting English in teaching and learning process to avoid the misunderstanding and to make sure that the instructions given by the lecturers are well received and understood by the students. Therefore, this changing of language used by the lecturers underlies this study to be conducted.

This study focuses on the type and reason of code-switching. Poplack (1980:614-615) identifies three types of code-switching. They are tag-switching, intersentential switching, and intrasentential switching. Besides, Wardhaugh (2006: 110) states that code-switching occurs because of many reasons, such as assert power, declare solidarity, and express identity.

kalau iki wes beres, we’ll move to the methodology,” it means the lecturer switches

language from English to Javanese using the intersentential switching type of code-switching. Besides, there are many reasons of code-switching provided for the example above. One of the reasons is the students have limited vocabulary in English. Therefore, switching language from English to languages they are more familiar with, in this case Javanese, will help them to understand the instructions. Moreover, the switching can also aim to make more interesting conversation with the students. In fact, code-switching, no matter what language is used, is needed to facilitate the teaching-learning process.

By having this topic, it is believed that the type and the reason of code-switching in classroom instructions spoken by the lecturers are able to be identified and classified.

B. Problem Formulation

1. What types of code-switching are used by the lecturers in the English students’ classrooms in Sanata Dharma University?

2. What are the reasons for using code-switching? C. Objectives of the Study

In short, the types of switching used by lecturers determine the reasons of switching. Therefore, in the objective of the study, the types and the reasons of code-switching are distinct but related one another.

D. Definition of Terms

According to Wardhaugh (2006:101), the particular dialect or language that somebody chooses to use on any occasion is called “code”, which is a system used

for communication between two or more parties. In short, in this case, code refers to a language that somebody picks up to use in the conversational interaction with other people.

Meanwhile, code-switching is the term used for the phenomenon of switching one language to another language. It is mentioned by Wardhaugh (2006:101) that code-switching occurs in conversation speakers’ turns or within a single speaker’s turn. Meaning to say, for example, when two people have a sort of small talk and one of them uses language that is not their mother tongue, it is called code-switching. So, concluded by Heller (1988:1), code-switching occurs when a person mixes two languages in a single sentence or in a conversation.

According to Poplack (1980:614) tag-switching, which is also known as emblematic switching, is a type of code-switching that deals with inclusion of tags, including interjections, idiomatic expressions, parenthetical, and even individual noun switches.

Poplack’s statement is added by Hoffmann (1991:112) who said that intersentential

switching occurs between clause or sentence boundary.

6 CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

This chapter provides three dominant parts of the study to be discussed. They are: review of related studies, review of related theories, and theoretical framework. Review of related studies elaborates the studies done by other researchers on similar topics. The studies similar to this study are taken from Ahmad’s and Sumarsih’s

studies. Each of them is reviewed to find out the similarities and differences in order to avoid the topics duplication. Moreover, in this chapter, some theories are reviewed and discussed to find a solid ground on which this study is carried on. Eventually, this chapter reviews the theoretical framework in which this part explains the contribution of the theories and reviews in solving the problems of the study.

A. Review of Related Studies

1. Ahmad’s study “Teachers’ Code-Switching in Classroom Instructions for Low English Proficient Learners”

Ahmad’s study discusses the perceptions of the learners about the use of

code-switching by the teachers in English Language classroom. By using questionnaire technique that is modified to include a 5-point Likert-type scale, instead of Yes-No answer type, Ahmad’s study is focused on finding out whether or not the use of code

learning success, learners’ affective support, and the future use of code-switching in

the classroom.

Although having a similarity in dealing with code-switching in the classroom instructions, this present study has differences on the focus of the study. Ahmad discusses 1) learners perceptions of teachers’ code-switching, 2) the relation of teachers’ code-switching and learners’ affective support, 3) the relation of teachers’

code-switching and learners’ learning success, and 4) the identification of the future use of code-switching in students’ learning.

Meanwhile, this present study emphasizes the types as well as the reasons of code-switching used by the lecturers in the classroom instructions as the teaching-learning process is underway.

2. Sumarsih’s study “Code Switching and Code Mixing in Indonesia: Study in

Sociolinguistics”

In her study, Sumarsih discusses the use of both code-switching and code-mixing in sort of a particular conversation in everyday life. Sumarsih’s study, which took

place in North Sumatra, tends to focus on both the use and the reason of switching and mixing. She finds out that the use of switching and code-mixing are not only involving English and Indonesian languages, but also involving North Sumatran’s local languages, Batak Mandailing and Batak Toba.

Sumatra, while this present study limits itself by only discussing lecturers’ types and

reasons of code-switching in the classroom instructions. B. Review of Related Theories

This subchapter provides some theories to be reviewed and discussed. There are three dominant parts related to code-switching to be reviewed and discussed in this subchapter. They are Sociolinguistics, Code, and Code-Switching.

a. Sociolinguistics

This following section provides many ways in which language and society are related. As a branch of Linguistics, Wardhaugh says

Sociolinguistics is concerned with investigating the relationships between language and society with the goal being a better understanding of the structure of language and of how languages function in communication. (Wardhaugh, 2006:13)

In addition, Hudson (1996:4) has described Sociolinguistics as follows:

Sociolinguistics is ‘the study of language in relation to society.’ In other words, in sociolinguistics we study language and society in order to find out as much as we can about what kind of thing language is. (Hudson, 1996:4)

Another sociolinguist like, for example, Gumperz (1971: 223) describes that sociolinguistics is an attempt to find correlations between social structure and linguistic structure and to observe any changes that occur.

studies in the four decades of sociolinguistic research have emanated from determining the social evaluation of linguistic variants.

Meanwhile, Chaika (1982:2) says that Sociolinguistics is the study of the ways people use language in social interaction. She adds that the sociolinguist is concerned with the stuff of everyday life, such as, for example, how you talk to your friends, family, and teachers, as well as to the storekeeper an-strangers-everyone you meet in the course of a day-and why you talk as you do and they talk as they do.

There are some definitions given by the sociolinguists to Sociolinguistics. Trudgill (1978:11), at first, says that ‘while everybody would agree that sociolinguistics has something to do with language and society, it is clearly also not concerned with everything that could be considered “language and society”.’

However, Downes in Trudgill’s glossary of terms (2003:123), characterizes sociolinguistic research as ‘work which is intended to achieve a better understanding

of the nature of human language by studying language in its social context and/or to achieve a better understanding of the nature of the relationship and interaction between language and society.’ (Wardhaugh, 2006:15)

b. Code

The general definition of code is that it is a system of rules to convert information, such as a letter, word, sound, image, or gesture, into another form or representation, sometimes shortened or secret, for communication through a channel or storage in a medium. (https://prezi.com/ppf0d_a787em/se/)

Meanwhile, through the perspective of sociolinguistics, Wardhaugh (2006:88) indicates, it is possible to refer to a language or a variety of a language as a code. Moreover, in the fifth edition of An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, Wardhaugh states

In general, however, when you open your mouth, you must choose a particular language, dialect, style, register, or variety– that is, a particular code. The ‘neutral’ term code, taken from information theory, can be used to refer to any kind of system that two or more people employ for communication. It can actually be used for a system used by a single person, as when someone devises a private code to protect certain secrets. (Wardhaugh, 2006:88)

Wardhaugh (2006:101) adds that code refers to the particular dialect or language that a person chooses to use on any occasion, a system used for communication between two or more parties.

These statements stated by Wardhaugh are supported by other sociolinguists. Rahardi (2001:21-22), for example, states that code can be defined as a system of speech that the application of the language has characteristics that are compatible with the background of the speakers, the speakers’ relationship with the interlocutors

Meanwhile, Marjohan and Poedjosoedarmo have thoughts about code as well. Poedjosoedarmo (1978:30) mentions that code usually has a form of a language variant that is significantly used for communication. Marjohan (1988:48), on the other hand, argues that code may be an idiolect, a dialect, a sociolect, a register or a language.

c. Code-Switching

Code-switching as a part of sociolinguistics concerns the switching of code from one to another in an occasion. Poplack (1980:583) states that code-switching is the alternation of two languages within a single discourse, sentence or constituent. Meanwhile, Duran, who supports the idea mentioned by Poplack, says that

Code-switching is probably strongly related to bilingual life and may appear more or less concurrently in the life of the developing language bilinguals especially when they are conscious of such behavior and then choose more or less purposefully to use or not to use it. (Duran, 1994:3)

Another sociolinguist, Hoffmann (1991:110) argues code switching is that it involves the alternate use of two languages or linguistics varieties within the same utterance or during the same conversation. Meanwhile, Wardhaugh states

People, then, are usually required to select a particular code whenever they choose to speak, and they may also decide to switch from one code to another or to mix codes even within sometimes very short utterances and thereby create a new code in a process known as code-switching. (Wardhaugh, 2006:101)

(1972:103) says that code switching has become a common term for alternate use of two or more language, varieties of language or even speech styles.

Therefore, according to Rahardi (2001:21), code-switching, in this study, is the use of two or more languages alternately, the varieties of language in the same language or perhaps the speech styles in a bilingual community.

Further, in discussing switching, the types and the reasons of code-switching is about to be discussed as well. In the two sections below, the discussion is about the types and the reasons of code-switching.

1. Types of Code-Switching

This section provides the general classification of code-switching. According to Poplack (1980:614-615), code-switching is divided into three types: tag-switching, intersentential switching, and intrasentential switching. Still according to Poplack (1980:614-615), tag-switching, which is also known by the name of emblematic switching, tends to deal with the fillers, tags, interjections, idiomatic expression, and even individual noun switches. Besides, while intersentential switching tends to occur at the phrase level or sentence level, between sentences, intrasentential switching often occurs within a sentence.

points in a monolingual utterance without violating syntactic rules. Next is intersentential switching that involves a switch at a clause or sentence boundary, where each clause or sentence is in one language or another. Intersentential switching can be thought of as a requiring greater fluency in both languages than tag-switching since major portions of the utterance must conform to the rules of both languages. For example is in the Puerto Rican bilingual Spanish-English speech given by Poplack (1980:614-615) Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en espa ol. ‘Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish and finish it in Spanish.’ On the other

hand, intrasentential switching is the switching that occurs within the clause or sentence boundary as in this example of Tok Pisin-English conversation What’s so

funny? Come, be good. Otherwise, yu bai go long kot. ‘What’s so funny? Come, be

good. Otherwise, you’ll go to court.’

Other sociolinguists such as Appel and Muysken (1987:118) states three different types of code-switching:

(a) Tag-switches involve an exclamation, a tag, or a parenthetical in another language than the rest of the sentence.

(b) Intra-sentential switches occur in the middle of a sentence.

(c) Inter-sentential switches occur between sentences, as their name indicates. (Appel and Muysken, 1987:118)

language. These parenthetical or 'tag' expressions typically express speaker mood or stance. Unlike tag-switching, intersentential switching is syntactically more restricted. Switches between clauses occur at clausal or sentential boundaries, or utterance boundaries in spoken discourse, with clauses from each language faithfully conforming to the rules of their respective languages. Intra-sentential switching, also referred to as code-mixing, involves the insertion of smaller morphosyntactic constituents, such as words or phrases, from one language into another.

These particular types of code-switching stated by sociolinguist above are often found in a conversational interaction, such as in the meeting, in the discussion, and in the classroom when teaching-learning process is ongoing. These types of code-switching tend to explain how bilinguals differ from monolinguals in the way languages are internalized. The use of these types of code-switching is actually related one another to the other section which discusses the reasons of code-switching in a conversation.

2. Reasons of Code-Switching

If the previous section discusses the types of code-switching, in this section, the discussion is about the speaker’s motivations, or the reasons, for using

code-switching in a conversational interaction.

As Mukenge (2012:587) stated that code-switching can be employed to create humor, Gal (1988:247) says code-switching is a conversational strategy used to establish, cross or destroy group boundaries; to create, evoke or change interpersonal relations with their rights and obligations.

Wardhaugh (2006:110) adds that code-switching can actually allow speaker to do many things such as assert power, declare solidarity, maintain certain neutrality when both code are used, express identity, and so on. Further, Wardhaugh (2006:104) also revealed that there are actually two kinds of code-switching: situational and metaphorical.

When a change of topic requires a change in the language used we have metaphorical code-switching. The interesting point here is that some topics may be discussed in either code, but the choice of code adds a distinct flavor to what is said about the topic. (Wardhaugh, 2006:104)

Wardhaugh (2006:104) says that the reasons for switching from one code to another is actually including solidarity, accommodation to listeners, choice of topic, and perceived social and cultural distance. The real example of the reason of code-switching as mentioned by Wardhaugh above, about solidarity, is the use of “saya”

and “aku.” These two Indonesian terms mean “I,” in English. When an Indonesian uses “saya,” it means that the person tends to show “power” and “distance” due to the

word that is often used in the formal situation such as in the meeting and press conference. Otherwise, when the person uses “aku,” it means that the person tends to show “solidarity” due to usage of the word that is often used in informal situation

such as in small talk and daily conversation. Although the word is used in a sort of informal situation, the word is believed to familiarize each other. After all, the motivation of the speaker is an important consideration in the choice. Moreover, such motivation need not be at all conscious, for apparently many speakers are not aware that they have used one particular variety of a language rather than another or sometimes even that they have switched languages either between or within utterances.

Zimbabwean society. For instance, as described above, sex is referred to as “sleeping

around”, or “pumping” and being sexually active is referred to as seeing the opposite

sex. Thus, a switch from ordinary language to euphemistic expressions within sentences or speech events is done first of all to save the face of the listener. Code-switching also enables the speaker to avoid using explicit and offensive language in the face of the listening audience.

In fact, when code-switching occurs, the motivation, or the reasons of the speaker is an important consideration in the process. Hoffmann (1991:115-116) states that there are some reasons the speaker uses code-switching in a conversation. There are 10 reasons stated by Hoffmann, which are:

1) Talking about particular topic

People sometimes prefer to talk about a particular topic in one language rather than in another, for example like expressing emotional feelings.

Sometimes, people feel free and more comfortable to express their emotional feelings in a language that is not their everyday language.

2) Quoting somebody

3) Being emphatic about something (declare solidarity)

Sometimes, a speaker who is talking in a foreign language switches the language into the native language in order to be emphatic about something, like, for example, the interlocutor does not understand or does not speak the foreign language as fluently as the speaker. Therefore, the speaker switches the language into native language, rather than keep speaking in the foreign language, in order to have a good interaction with the interlocutor.

4) Interjection (inserting sentence fillers or sentence connectors)

Interjection is words or expressions, which are inserted into a sentence to convey surprise, strong emotion, or to gain attention. Interjection is a short exclamation like: Darn!, Hey!, Well!, Look!, etc. They have no grammatical value, but speaker uses them quite often, usually more in speaking than in writing. Language switching among bilingual or multilingual people can sometimes mark an interjection or sentence connectors. Otherwise, it may also happen unintentionally.

5) Repetition used for clarification

6) Expressing Identity

Code switching can also be used to express group identity. This happens because the way of communication of one community is different from the people who are out of the community.

7) Intention of clarifying the speech content for interlocutor

According to Arimasari (2013:33) when bilingual or multilingual person talks to another bilingual/multilingual, there will be lots of code switching occurs. It means to make the content of his speech runs smoothly and can be understood by the listener. A message in one code is repeated in the other code in somewhat modified form.

8) To soften or strengthen request or command

Arimasari (2013:33) in her thesis explains that, for Indonesian people, switching from Indonesian into English can also function as a request because English is not their native tongue, so it does not sound as direct as Indonesian. However, code switching can also strengthen a command since the speaker can feel more powerful than the listener because he can use a language that everybody cannot.

9) Because of the real lexical need

10)To avoid other people join the conversation

Sometimes people want to communicate only with certain people or community they belong to. Therefore, to avoid the other community or interference objected to their communication by people, they may try to exclude those people by using the language that nobody knows.

C. Theoretical Framework

In order to answer the problems on the problem formulation, at first the discussion on the theory takes place in understanding the basic concept of sociolinguistics, code, and code-switching. As known, these three dominant parts are closely related and are the basic understanding to the topic being discussed in this study.

code-switching, in which it is an alternation of code from one to another in a conversational interaction.

Based on these arguments on code-switching stated by sociolinguists, the discussion further continues to the problems that have to be solved. They are the types and the reasons of code-switching. First of all, in order to answer the first problem on problem formulation about the types of code-switching, the theory mentioned by Poplack (1980:614-615), who categorizes the three types of code-switching, is used. Moreover, the theories mentioned by other sociolinguists, such as Romaine (1995: 122-123), Hoffmann (1991:112), Appel and Muysken (1987:118), are, more or less, similar from the one proposed by Poplack. These theories then are considered as the supporting theories for answering the first problem on the types of code-switching.

22 CHAPTER III

METHODOLOGY

In this chapter, the study discusses the object, the approach, and the method of the study. In the object of the study, it puts forward code-switching used in lecturers’ classroom instructions. Meanwhile, the approach of the study introduces the application of approach which supports the study. For the method of the study, it is focused on discussing how the data are collected, organized, and categorized.

A. Object of the Study

As taking place in the field of linguistics, especially sociolinguistics, this study discusses code-switching. Code-switching used by the lecturers in giving instruction in the classroom is the object of this study. Further, this study particularly discusses code-switching, the change of language use, which, in this case, includes three different languages: English, Indonesian, and Javanese, in the classroom instructions given by the lecturers.

This study limited itself in only investigating six lecturers who taught seven different courses. In addition, one of the lecturers taught two different subjects. Moreover, since it contained a lot of instructions, it could provide useful data.

B. Approach of the Study

approaches are considered as the most suitable approaches to answer the questions in problem formulation.

Boztepe (2003:3), in his paper, states that the structural approach of code-switching is primarily concerned with grammatical aspects. The focus of structural approach is to identify syntactic and morphosyntactic constraints on the code-switching. On the other hand, sociolinguistic approach sees code-switching as a discourse phenomenon focusing its attention on questions such as, for example, how social meaning is created in code-switching and what specific discourse functions it serves.

In short, the sociolinguistic approach analyzes code-switching from the social context, for instance, what causes code-switching to occur in a conversation. On the other hand, the structural approach is more inclined to the grammatical aspects of code-switching.

These two approaches are used in order to identify the objectives of the study, which are the type of code-switching and the reason of code-switching in the instructions given by the lecturers in the classroom when teaching-learning process is underway.

C. Method of the Study

1. Data Collection

There were six lecturers from English Department of Sanata Dharma University Yogyakarta to be interviewed for the investigation of this study. The classroom instructions given by the lecturers who taught particular courses were the primary data for this study. The data were collected in the classroom when teaching-learning process was underway by using recording techniques and notes.

For the first step, the writer attended each class, one by one, those six lecturers gave lecture. It started from the class of “Lecturer 1” who taught Introduction to

English Test (INTET), “Lecturer 2” who taught “English Structure” after that,

“Lecturer 3” who taught Stylistics, and then “Lecturer 4” who taught two different

courses, which are Language Research Methodology and Pragmatics, followed by the History of Modern Thought course taught by “Lecturer 5, and finally “Lecturer 6”

who taught Interpreting. The process of gathering the whole data needed a couple of weeks because the writer had to adjust to each lecturer’s teaching schedule in class.

After finished doing the first step, which was attending each class, for the next step, in each class where those lecturers gave the lecture, the writer used a voice recorder on the smart phone to record the interaction, such as explanations, instructions, or conversations, each lecturer had in the classroom. The process of recording was done without the lecturers’ acknowledge. Besides, the writer was not

lecturers said if there was any code-switching detected. The process of gathering the data in each class started since the class was begun until the class was over. Furthermore, all the interactions each lecturer had in the classroom from the voice recorder were transformed into the script for the analysis.

As known, the process of gathering the data was not only from the classroom instructions, but also from the interview with the lecturers. The interview was done by using interview techniques, recordings, and notes. The process of gathering the data from the interview was a bit different from gathering the data in the classroom instructions, though the techniques were similar. For the first step, the writer made an appointment with each lecturer to be interviewed. Along with that, the writer explained the topic of this study, so the lecturers knew why they were interviewed. As known, the interview was held mostly in the lecturers’ offices. Further, before the

interview began, the writer prepared the notes, a pen, and smart phone for recording the interview. When the interview started, the smart phone recorded the interview. Meanwhile, the writer took notes on the lecturers’ answers. The questions asked to

the lecturers in that interview were like, for example, “Why do you think about code -switching in the classroom?” and “Why did you use it in class when you were lecturing?” As the interview finished, the data, especially from the voice recorder,

2. Data Analysis

The data on the instructions given by the lecturers in the classroom were analyzed and the interview with the lecturers followed.

The data, from the classroom instructions, which had been transformed into the script, were organized in the form of table. It showed the expression of code-switching in classroom instructions given by the lecturers. After that, these data were classified into three different parts to identify the first problem; the type of code-switching. And then, the writer tried to identify the reason of code-switching from the interview with the lecturers. It definitely related to the lecturers’ answers of the interview to the theory used for this study.

27

CHAPTER IV

ANALYSIS RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

This chapter is divided into two main sections, which are (A) answer for the types of using code-switching in the classroom instructions and discussion, and (B) answer for the reasons of using code-switching in the classroom instructions and discussion. Here the data are used for the discussion and finding out the answer of this study. The data from classroom instruction are used in the section (A). Meanwhile, the data from the interview with the six lecturers are used in the section (B). Further, the theories presented in the reviews are applied in this part. The theory stated by Poplack (1980:614-615) and the supporting theories stated by other sociolinguists are used for the discussion and finding out the answer in the section (A), the types of code-switching. Meanwhile, the main theory stated by Wardhaugh (2006:110) and supporting theories stated by sociolinguists like Mukege (2012:587) and Gal (1988:247) are used for the analysis and finding the answer in the section (B), the reasons of code-switching.

A. Types of Using Code-Switching in the English Students’ Classrooms and Discussion

a. Tag-Switching

Tag-switching is one of three types of code-switching that deals with the inclusion of a tag. Worth noting that tags in tag-switching are not only literally dealing with tags, but also dealing with words or phrases related to tag-switching, which includes fillers such as, actually, basically, usually, as mentioned by Poplack (1980:614-615). Tag-switching also involves the insertion of a parenthetical expression, such as discourse markers or sentence adverbial (Bond, 2010:134) such as, well, so, right. Tag-switching can be found in a statement or in a question in the initial position, as seen in the Table 1 below:

Table 1. Tag-switching in the initial position

No Expression Language Content

English Indonesian Javanese

1 Biasanya, forty people. √ √ -

2 Biasanya, penjelasan kalian tidak brief. √ √ -

3 Logikanya, it is an analogy, kan? √ √ -

4 Lanjut, number three. √ √ -

5 Kemudian, we may say there used to be a tree.

√ √ -

6 Saya pikir, mahasiswa ini fail to understand what is assumed.

√ √ -

7 Dengan kata lain, presupposition will be the background.

√ √ -

8 Katanya, there is no Pragmatics test. √ √ -

9 Sementara itu, ITP adalah Institutional Test Program.

All of the data in Table 1 are the code-switching from English to Indonesian. Moreover, each of the data in Table 1, started from number 1 to 9, is seen as tag-switching, including certain set phrases, like in data number 6, 7, and 9. Mostly, the data in the Table 1 are conjunctions. Take a look at data number 1 and 2, for example. Those two are used at beginning of the sentence as sentence fillers. They are spoken as a function to signal the students that the lecturer has paused to think but has not even yet finished talking. In the data number 1, the lecturer said “biasanya,” as a

sentence opener while he was thinking the following words to finish the sentence.

Meanwhile, another example, in data number 4 to 7, the tags are considered as conjunctive adverbs or conjunctions, which are parts of discourse markers. Discourse markers are used to direct, or redirect, the flow of conversation without adding any significant meaning to the discourse. In data number 4, for example, the lecturer said “lanjut,” which in English is “next,” in order to sequence the content of the

conversation. By seeing the context of the sentence, it is known that the lecturer was directing the students to continue discussing the following number, after having finished discussing the previous number.

Another example is in data number 6 and 7. While in data number 6, the lecturer said “saya pikir,” which in English is “I think,” to show a personal point of view on a

student that was being talked about, in data number 7, “dengan kata lain,” or “in

other words” in English, is used to explain what is being talked in a kind of different

Further, in discussing tag-switching, this type of code-switching does not only occur at the beginning of the sentence, like in the Table 1, but it also occurs at the end of the sentence, as seen in the Table 2 below:

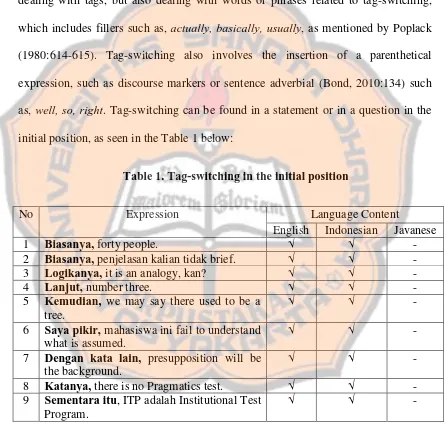

Table 2. Tag-switching in the final position

No Expression Language Content

English Indonesian Javanese

10 Logikanya, it is an analogy, kan? √ √ -

11 If I’ll talk to you another time artinya I’ll talk to you in the future, kan?

√ √ -

12 When somebody says something berarti kita harus tahu assumption-nya, kan?

√ √ -

13 Though we are half dead, we are alive. Tidak ada yang setengah mati dan setengah hidup, kan?

√ √ -

14 My car ran properly, kan? √ √ -

Tag-switching is not only found at the beginning of a sentence, but also at the end of a sentence. Each tag occurred at the end of the sentence in the Table 2 above is also known as a question tag, in which a statement is turned into a question by adding a question tag “kan.” By seeing data number 10 to 14 in Table 2 above, the utterance

of each tag takes place at the end of the sentence. This is done in order to ensure whether or not what is said is right. For example, in data number 11, after giving an explanation about the lecture, the lecturer said “kan” or “right” in English, followed

by question mark, to ask whether or not his explanation was correct. After all, the explanation about “kan” in data number 11 applies to data number 10, 12, 13 and 14,

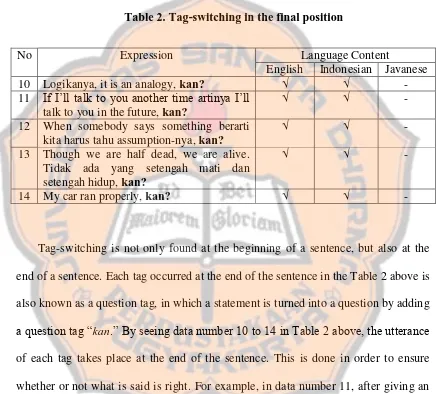

Tag-switching tends to occur in the form of discourse markers, as well as interjections, as seen in the Table 3 below:

Table 3. Tag-switching at discourse markers and interjection

No Expression Language Content

English Indonesian Javanese 15 Teman-teman! Is there any one of you

have ever taken a TOEFL test?

√ √ -

16 Teman-teman! If you want to take the real

TOEFL test, … √ √ -

17 Jadi, this paper becomes your final paper. √ √ -

18 Jadi, whatever we say will lead… √ √ -

19 Jadi, harga bisa berubah. It can change. √ √ - 20 Jadi, kalian cuma prepare a scrap of paper. √ √ - 21 Some of them are facts. Jadi, kalian

jangan berspekulasi apapun.

√ √ -

22 Perhatian! To watch this video kalian harus menggunakan loud speaker.

√ √ -

23 Halo! Ada yang tahu this one? √ √ -

While some of the data in Table 3 above occur in the form of discourse markers, the other occurs in the form of interjection. In data number 17 to 21, for example, “jadi” which in English is “so” is a part of discourse markers. In general, it marks the

beginning of a new part of the conversation. It is also used to refer back to statements that have already been mentioned previously. Take a look at data number 20, for example, “jadi” in that context is a tag that is used as a conclusion of a statement that

has just been mentioned previously. In data number 17, on the other hand, “jadi” is

Some of the data in Table 3 occur in the form of interjection. Interjection is also a part of tag. Interjection is used for giving expressions to people. The data which are categorized into interjection in the Table 3 are the data number 15, 16, 22, and 23.

In data number 15 and 16, “teman-teman”, which means “friends” or “mates”,

was uttered by the lecturer to address the students. Moreover, in data number 22 and 23, the lecturer called “halo!” and “perhatian” as well. These utterances, including “teman-teman,” were used by the lecturers to attract the students’ attention before

giving the statements or asking questions.

Tag-switching often takes place in interjection. Interjection with its short sound, word, or phrase is spoken suddenly to express the speaker emotion, such as surprise, horror, or pain.

b. Intersentential Switching

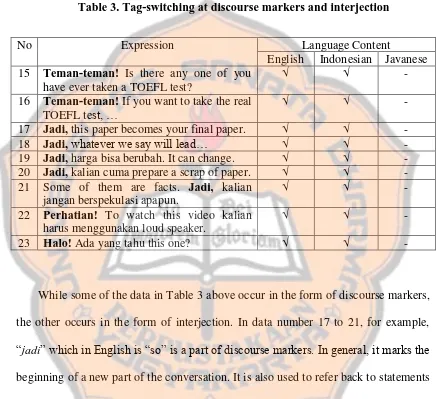

Table 4. Intersentential switching at the conditional sentence

No Expression Language Content

English Indonesian Javanese 24 Kalau lagi galau, pusing, atau sakit, your

TOEFL score will not be satisfactory.

√ √ -

25 Kalau saya tiba-tiba mengulangi hal yang sama, please remind me.

√ √ -

26 So, jika kenyataannya itu dibalik, you’ll

see the… √ √ -

29 For example, kalau dapat di Google, write down the source.

√ √ -

30 Kalau tidak dibaca, we can’t even discuss it. ceweknya pasti bakal klarifikasi kalau itu bukan anjingnya.

√ √ -

In the data number 24 to 30, for example, the switch of code occurs at the “if clause” of conditional sentence. In the data number 24, particularly, in a full conditional sentence, the switch of code occurs at the clause level, which is the “if

clause,” of conditional sentence. The lecturer opened the conversation by using Indonesian language in the “if clause” before changing into English in the main

clause of the sentence. By seeing the form of the sentence, it is known that it is the type 1 of the conditional sentence, in which the lecturer tried to explain the possible condition to happen to the result of TOEFL test if the students were over thinking, worried, or sick.

Another example is in the data number 27. In the data number 27, the conditional sentence is similar to data number 24 where the switch of code occurs in the “if

clause.” The type of the conditional is similar, as well, which is the type 1, or the first

type of conditional. It explains the possible condition to happen in the future based on what is done in the present. However, in this case, the difference lies on the code or the language. Meaning to say, the switch of code in this clause involves Javanese language. The switch occurs from Javanese into English followed in the next clause.

Furthermore, in the data number 30, although the switch still occurs in the “if

lecturer expected the students to read the material that was given. Otherwise, they could not discuss the material together at all.

When the switch of code in data number 24 to 30 in the Table 4 occur in the “if

clause,” otherwise, in the data number 31 to 35, the switch occurs at the main clause

of conditional sentence. Take a look at data number 31, for example. As mentioned, the switch of code in data number 31 occurs at the main clause of conditional sentence. The same thing happens to data number 32 and 33 as well. The form in these three numbers is actually similar. It is the type zero of conditional sentence. In data number 32, for example, the switch, “kita tahu dia pasti punya nama,” or “we

know he definitely has a name” in English, which occurs in the main clause is the

result of “if clause.” The same form and explanation in data number 32 also applies to

data number 33. However, in this case, the lecturer tried to explain the material by using a different example.

While the switch of the previous numbers in the Table 4 occur at the clause level, whether at the “if clause” or main clause, in the data number 36 and 37, the switch of

code occurs in the full conditional sentence. In data number 36, the switch of code occurs in both “if clause” and main clause of conditional sentence. The type of

conditional sentence itself is the type zero. It gives the general truth or fact. Therefore, in this case, as seen, in the data number 36, which is “kalau mau ke toilet,

kalian harus antri” or in English means “If you want to go to the toilet, you have to

queue,” the lecturer tried to give an explanation to the students about the fact to

Another example of the switch in the full conditional sentence is in the data number 37. A little bit different from the previous data number 36, data number 37 occurs in the type 2 or the second type of conditional sentence. It can be proved by seeing the form of the sentence, “kalau cowok ini baik hati, kooperatif, ceweknya pasti bakal klarifikasi kalau itu bukan anjingnya” or in English would be like “if this

guy were kind, corporative, the girl would definitely clarify it is not her dog.” In the context of the lecture, the lecturer tried to explain to the students about the possibility that probably would happen as the result of the condition if the guy were kind.

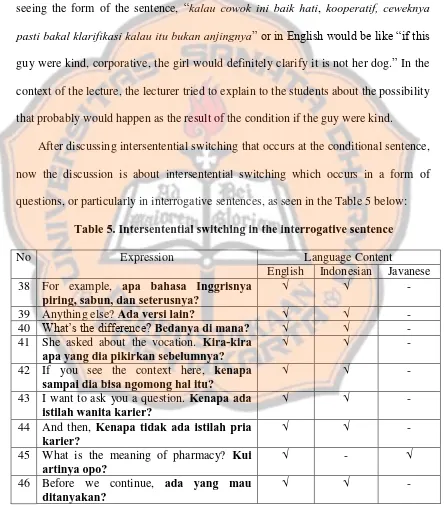

After discussing intersentential switching that occurs at the conditional sentence, now the discussion is about intersentential switching which occurs in a form of questions, or particularly in interrogative sentences, as seen in the Table 5 below:

Table 5. Intersentential switching in the interrogative sentence

No Expression Language Content

English Indonesian Javanese sampai dia bisa ngomong hal itu?

47 Questions? Ada pertanyaan? √ √ -

48 Are you ready? Sudah siap? √ √ -

49 Apa yang pertama kali dia ucapkan? Does anyone know?

- √ -

50 Come on! Masih ra dong meneh? √ - √

51 What is the next information we can get? Ada yang tahu informasi berikutnya?

√ √ -

As seen in the Table 5 above, from data number 38 to 51, the switch of code occurs in the form of interrogative sentence. Most of the data occur from English into Indonesian. However, there are also data, in which data number 45 and 50, which involve Javanese language.

First of all, take a look at data number 43 and 44 that are related one another. These two questions, in each number, actually refer to a term “karier,” or “career” in

English, which is more suitable when paired with “woman” rather than “man” in the

context of Indonesian language. Therefore, the lecturer asked the students why there is only the term “wanita karier.”

Moreover, another example, like in data number 45, “kui artinya opo?” which

means “what does it mean?” in English, occurs in a complete interrogative sentence

Furthermore, take a look at data number 46. Here, the sentence is divided into two parts. The first part is the clause that occurs in English while the other clause occurs in Indonesian. The lecturer opened the sentence by using English in the first clause before closing the sentence with a question, in Indonesian. The explanation about the data number 46 also applies to the other data number 38 and 42.

Meanwhile, in the data number 41, the switch of code occurs after a sentence in the first language, which is English, has been completed and the following sentence starts with a new language. Meaning to say, the “kira-kira apa yang dia pikirkan

sebelumnya?” occurs after the sentence “she asked about the vocation”is completed. In addition, in the data number 50, the switching occurs after the phrase is uttered. Meaning to say, the interrogative sentence “masih ra dong meneh?” occurs

after the phrase “come on!” is uttered.

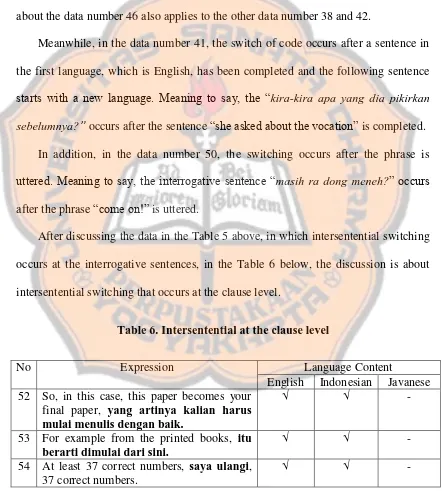

After discussing the data in the Table 5 above, in which intersentential switching occurs at the interrogative sentences, in the Table 6 below, the discussion is about intersentential switching that occurs at the clause level.

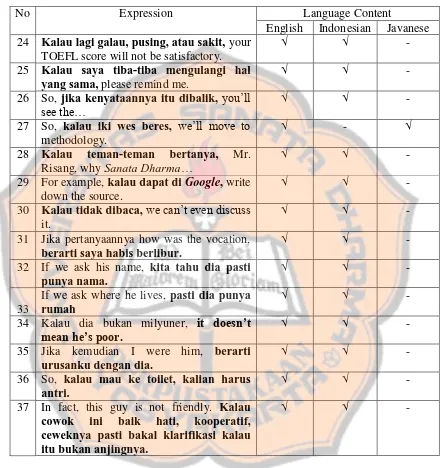

Table 6. Intersentential at the clause level

No Expression Language Content

English Indonesian Javanese 52 So, in this case, this paper becomes your

final paper, yang artinya kalian harus mulai menulis dengan baik.

√ √ -

53 For example from the printed books, itu berarti dimulai dari sini.

√ √ -

54 At least 37 correct numbers, saya ulangi, 37 correct numbers.

55 Entah dia enggak punya waktu, sibuk, atau sakit perut, that’s all speculation.

√ √ - 61 Thematically speaking, mereka saling

melengkapi.

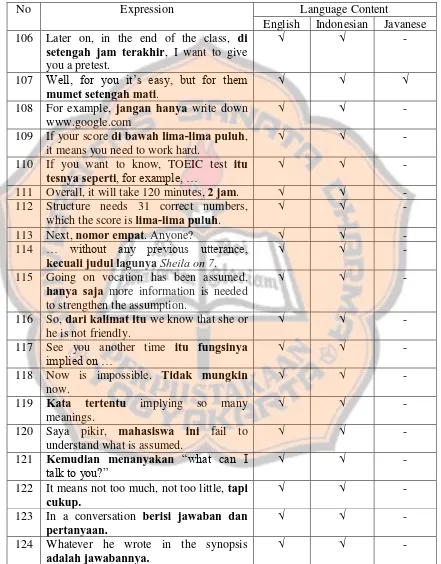

In the data number 52 to 68 in the Table 6 above, the switch of code occurs at the clause level. Some of the switches in each of the data occur at the beginning of the sentence as the openers. Meanwhile, the switches in the rest of the data occur at the end of the sentence, whether after the words, phrases, or clauses.

although there is also a switch of code that occurs in the second clause of the data number 59.

Another example is in the data number 68, in which it has a similarity to the data number 65. The sentence is opened in Indonesian language and is closed by English. However, unlike the data number 65 that the sentence contains of two clauses, in this case, the sentence contains of a clause and a word or, a tag, which is followed by question mark at the end of the sentence. First of all, the switch occurs at the clause level in the beginning of the sentence, “kayaknya ini mudah saja,” or in English “seems like this is easy,” before “right?” or in other words, “isn’t it?” said at the end

of the sentence as an utterance to ask or to ensure what is said is correct. The same explanation on data number 65 applies to the data number 66. However, in the case of the data number 66, the word or a tag at the end of the sentence occurs in Indonesian language.

Moreover, in the data number 62, as same as the other data, the switch of code occurs in the beginning of the sentence. However, unlike the previous data that in the sentence contains of either a word or a clause, in this case, there is a phrase that comes after the clause, which closes the sentence.

you have to start writing well,” occurs after the clause “this paper becomes your final

paper.” The same explanation on the data number 52 applies to the data number 57

and 64 as well. The switch in these two data occurs after the clause in the beginning of the sentence.

Moreover, another example is in the data number 58 and 61. After all, the switching is similar to the data in the previous number, data number 52, in which it occurs at the end of the sentence. However, unlike the previous data that the switching occurs after a clause, in this case, the switching occurs after the phrase. While in the data number 58, the switching occurs after the phrase “for example,” in the data number 61, the switch of code occurs after the phrase “thematically

speaking” is uttered.

Furthermore, unlike the previous data that the switch of code occurs after whether phrase or clause, in the data number 56 and 63, the switching occurs after the word in the beginning of the sentence. In these two data, “kalian jangan berspekulasi

apapun,” which means “you do not speculate anything,” and “harga bisa berubah,”

which means “the price can change,” occur after the word “jadi,” or in other words

“so,” begins the sentence. This explanation upon the data number 56 and 63 also

applies to the other data, which are data number 60 and 67, in which these two have similarity that the switch occurs after the word in the beginning of the sentence.

correct numbers” said by the lecturer. And then, the switch “saya ulangi” that is “I repeat” in English is followed, before “37 correct numbers” said at the end to close

the sentence.

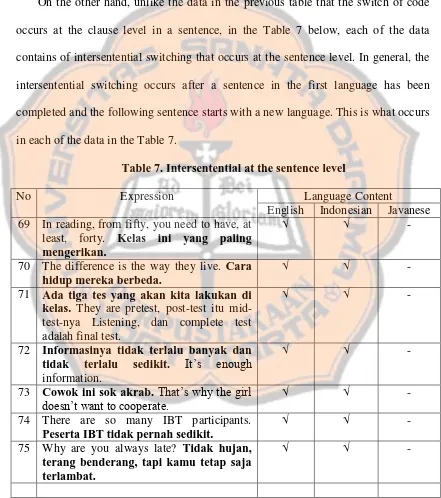

On the other hand, unlike the data in the previous table that the switch of code occurs at the clause level in a sentence, in the Table 7 below, each of the data contains of intersentential switching that occurs at the sentence level. In general, the intersentential switching occurs after a sentence in the first language has been completed and the following sentence starts with a new language. This is what occurs in each of the data in the Table 7.

Table 7. Intersentential at the sentence level

No Expression Language Content

76 Books are precious. Semua buku yang berhubungan dengan kuliah ini tidak saya buang.

√ √ -

77 Things have changed. Yang tidak bisa dibayangkan adalah lab. jurnalistik itu dulunya tangga ke lantai dua.

√ √ -

78 Kalian juga tidak bisa bayangkan kalau di sana itu dulunya ada ruang-ruang kelas. It was a hallway, long ago.

√ √ -

79 Orang-orang dulu lebih kaget lagi ketika tahu bahwa ruang-ruang kelas sudah berubah. They all are surprised kamu jadi aku. Two opposite reality.

√ √ -

Take a look at data number 69 and 70. These two numbers are the exact examples of the explanation mentioned in the previous paragraph. First of all, the sentence is opened by using English as the main language used in the classroom. After that, when the sentence in English has been completed, the language is switched into a new language, which is Indonesian, in the following sentence.