A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Nurse-led Interventions to Promote Healthy Lifestyles of Clients in Primary Healthcare

Damayanti S, MR

Nursing Program, Faculty of Medicine Udayana University [email protected]

Background:

Health promotion provision is regarded as an integral component of the health professional’s role, particularly for nurses working in a primary healthcare. However, the prevailing evidence leaves in question the effectiveness of health promotion interventions through which nurses promote healthy lifestyles to clients in primary healthcare.

Objective:

To specifically identify the effectiveness of nurse-led interventions for promoting healthy lifestyles amongst clients in primary healthcare, and this shown by several changes in behavioural indicators and clinical outcomes.

Methods:

A computerized literature search was carried out to find studies that fulfil the inclusion criteria. The search period was 1st of January 1995 through recent date. The search was restricted to studies undertaken in human and reported in English. The identified original publications were assessed based on the relevance of the titles and the inclusion criteria. Duplication publications were eliminated. The relevant publications were then assessed independently for their methodological rigor by three reviewers. The standardised assessment and review instrument and the standardised data extraction tool for experimental studies from the Joanna Briggs Institute were employed.

Results:

The most relevant ten publications passed the critical appraisal step. All studies involving randomised controlled trials with a mixed methodological quality. The participants in the studies represented diverse groups of the population. The studies’ interventions varied widely, from single-focus interventions to those applied across several health behaviours (multiple risk factors); and interventions to address coronary heart disease risk factors.

Conclusions:

There is some encouraging evidence that nurse-led interventions are effective in promoting healthy lifestyles amongst the primary healthcare clients. The interventions that appear to be most successful include led nutritional education programs, exercise on prescription, health checks, and nurse-led health promotion consultation. A more focused clinical question and systematic literature search is recommended for further relevant secondary studies. Findings from this review might be useful to inform the development of appropriate health promotion programs targeting primary healthcare clients.

Keywords:

INTRODUCTION

Background

In recent years, a number of studies have been conducted to investigate the link between

non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and their determinants. The mortality and morbidity

related to NCDs are caused by the cumulative effect of metabolic risk factors i.e. overweight

and obesity, high-blood pressure, raised-blood sugar and high-lipid level (1). These metabolic

risk co-morbidities are predisposed by some preventable behavioural risk factors or

NCD-related lifestyles, such as smoking/tobacco use, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity and alcohol

misuse (1, 2). Encouraging people to adopt healthy lifestyles through health promotion (HP)

is one of the interventions endorsed by the World Health Organisation to tackle the

determinants of NCD-related lifestyles (1).

The Ottawa Charter (3, p.1) defines HP as ‘...the process of enabling people to increase

control over, and to improve, their health’. The HP activity is underpinned by a social view of

health; and this means that only by addressing the cultural, environmental, biological,

political and economic factors influencing population’s health can we improve their health

status (1, 4, 5). There are several HP approaches currently in place, focused either on

individuals, groups, communities or whole populations. Naidoo and Wills (6), for instance,

classify the HP strategy into several categories; where each of the approaches represents

different ways of working, namely medical preventive, educational, behaviour change,

empowerment and social-change. Talbot and Verrinder (4) offer another framework to depict

the relationships amongst the available HP strategies, labelled as ‘a continuum of HP

strategy’. This framework shows that interventions which focus on a population’

socio-environmental aspects are placed at one end of the continuum, whilst the individual-focused

interventions occupy the opposite end (4). The socio-environmental approach can be

conducted by creating healthy public policies and supportive environments, and

strengthening community actions (4). The behavioural approach is undertaken by providing

health education or information to improve individuals’ HP skills (4, 7). The

individual-focused interventions also can be delivered through a medical approach by means of

screening, individual’s risk-factor assessment, immunisation and surveillance (4).

HP supported by the structural approach of primary healthcare (PHC) and the Ottawa

Charter (4), is about empowering clients to integrate healthy habits into their lives and to live

component of the health professionals’ role working in PHC context, particularly nurses. Nurses are appropriately positioned to promote healthy-lifestyles (8), as nurses interact with

many people at key points in their lives (9). Indeed, Kendall (10) argues that, nurses remain

the primary advocates and HP providers to clients in PHC settings.

As a first tier of health provision, PHC provides an essential context for HP because of its

unique characteristics. PHC offers a ‘universal access’, because at some point of their lives,

people will come into contact with PHC services. Then, being trusted and regarded as

credible person by the general population, health practitioners working in PHC may have a

greater opportunity to influence people’s knowledge, attitudes and beliefs on health (6). Other

characteristics that may put the PHC centre as an appropriate site to promote people’s healthy

behaviours are its affordable and acceptable services (4). PHC centres also offer better access

because they are located within community settings, and facilitate better communications

between service users and providers as they meet on more equal terms (6). Moreover,

adequate provision of PHC level services will often imply that more specialised

hospital-based services are unnecessary (6), leading to a more cost-effective healthcare practice.

To date, there are quite a lot of primary and secondary studies have been conducted to

investigate the effectiveness of HP interventions within PHC practice led by a large range of

healthcare practitioners addressed to various types of clientele (11-18). The initial literature

search also identified some studies with diverse findings and approaches have been carried

out to assess the effectiveness of nurse-led HP interventions in different settings (19-24).

Other researchers also have investigated the effectiveness of nurse-led HP interventions

compared with those initiated by other health practitioners (25).

These preliminary findings demonstrate that sufficient numbers of studies in HP within

PHC context have been carried out. The studies varied considerably in terms of their target

populations, interventions, and outcomes. However, the prevailing evidence leaves in

question the effectiveness of HP interventions through which nurses promote healthy

lifestyles to clients in PHC. Therefore, this review was carried out to specifically and

systematically search, collate and synthesise studies investigating this phenomenon. Findings

from this review might be useful to inform the development of appropriate HP programs

targeting PHC clients. As nurses are considered to be the frontline staff with pivotal roles in

Review Question/Objectives

The review question was: What is the effectiveness of nurse-led interventions to promote

healthy lifestyles of clients in PHC?

The objective of this review was to specifically identify the effectiveness of nurse-led

interventions for promoting healthy lifestyles amongst clients in PHC, and this shown by

changes in the following behavioural indicators and clinical outcomes:

1. Healthy eating habit, including overweight and obesity indicators

2. Physical activity levels

3. Smoking behaviour

4. Alcohol misuse

5. Morbidity and mortality prevalence caused by lifestyle-related diseases

METHODS

Inclusion Criteria

Types of studies

This review considered studies targeting PHC clients (individuals or groups) who received

nurse-led HP interventions. The studies were conducted either within institutions (e.g.

primary cares, schools, workplaces, etc.) or in community settings (e.g. clients’ homes).

Types of interventions

This review included any nurse-led interventions undertaken to promote healthy lifestyles for

clients in PHC, either single or multiple focus interventions. The included interventions were

those that focused on preventing or delaying onset of diseases by changing from unhealthy

lifestyles to encouraging clients to adopt the healthy ones. Interventions led by other

healthcare practitioners with nurses as the supplementary practitioner or nurse-led HP

conducted outside the PHC context were excluded.

Types of outcomes

This review considered the following primary outcomes:

Changes toward healthier dietary pattern e.g. sufficient intake of fruit and vegetables/fibre, decreased intake of fat and/or sodium

Changes in physical activity pattern e.g. increased physical activity levels

Changes in alcohol intake e.g. a reduction in the amount of daily intake

Clinical outcomes related to morbidity caused by unhealthy lifestyles such as overweight or obesity, high-blood pressure, raised blood sugar and lipid. The longer-term related

morbidity or mortality includes cerebro-vascular diseases, diabetes, cancer and chronic

respiratory diseases.

Types of studies

This review considered any related meta-analysis or systematic reviews of RCTs and

RCTs that evaluate the effectiveness of nurse-led interventions to promote healthy lifestyles

amongst clients in PHC.

Search Strategy

A computerized literature search was carried out to find studies that fulfil the inclusion

criteria. The following databases were searched in April 2013: PubMed, CINAHL and

Scopus. Several keywords were used in combination in the search, namely, health promotion

(Medical Subject Headings ‘MeSH’), nurses (MeSH), primary health care (MeSH). The

search period was 1st of January 1995 through recent date (April 2013). The literature search

was also restricted to studies undertaken in human and was filtered to include only research

reported in English because the reviewer was constrained by time, resource and facilities for

translating the non-English publications. To confirm the search strategy, an experienced

librarian was consulted. The reference database EndNote was used to catalogue the articles

that were identified.

Study Selection

First, the identified original publications were assessed based on the relevance of the

titles. Then, the author read the relevant abstracts using the inclusion criteria previously

mentioned. Screening and eliminating for duplication publications was subsequently

conducted. Having finished these steps, the author read the relevant publications in their

entirety. The relevant publications were then assessed independently for their methodological

rigor by three reviewers.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

The reviewers critically appraised the studies’ methodological validity prior to inclusion

in the review using the standardised Assessment and Review Instrument from the Joanna

that arose amongst the reviewers were resolved through a discussion until consensus was

reached.

Data Extraction

The data from studies which passed the methodological quality assessment process were

extracted from papers using the standardised data extraction tool. This review used the JBI

data extraction form for experimental studies. This tool includes specific details about the

interventions, populations, study methods and outcomes of significance to the review

question and specific objectives.

Data Synthesis

Where applicable, a meta-analysis or statistical pooling to measure the combined effect

(average effect size or single-effect estimate) of the interventions from the chosen literature

would be conducted using the Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument

(JBI-MAStARI). However, due to lack of homogeneity across the included studies it was not

possible to statistically pooling the data. Therefore, the results were reported in a narrative

form to conclude the overall findings on current available approaches concerning nurse-led

interventions to promote healthy lifestyles amongst clients in PHC.

RESULT

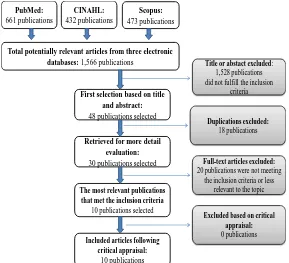

The following figure outlines the processes undertaken to select the publications.

PubMed: 661 publications CINAHL: 432 publications Scopus: 473 publications

Total potentially relevant articles from three electronic databases: 1,566 publications

First selection based on title and abstract:

48 publications selected

Title or abstact excluded: 1,528 publications did not fulfill the inclusion

criteria

The most relevant publications that met the inclusion criteria

10 publications selected

Full-text articles excluded: 20 publications were not meeting

the inclusion criteria or less relevant to the topic Duplications excluded:

18 publications Retrieved for more detail

evaluation:

30 publications selected

Excluded based on critical appraisal: 0 publications

Included articles following critical appraisal:

[image:10.595.154.443.473.736.2]10 publications

The initial search from three databases mentioned above resulted in 1,566 publications.

Forty eight publications were relevant based on the title and abstract. After excluding for

duplications, 30 publications were retrieved for more detail evaluation. This review was

restricted to include only ten publications that met the inclusion criteria, whilst also best

representing the existing literature pertinent to the chosen topic. The most relevant ten

publications were selected for critical appraisal. There was no publication excluded following

the critical appraisal.

Study Type and Quality

The included publications were all studies involving RCTs with a mixed methodological

quality. Eight studies employed a-two-arm study design (21, 26-32), one adopted a-three-arm

RCT (33) and one trial included four intervention arms (34). The size of samples in seven

studies were determined based on sample-size calculations or reported study power (21,

26-28, 30, 32, 33); but three publications did not clearly address this issue (29, 31, 34). To assign

the participants into a treatment group, most of the studies (80%) employed a true

randomisation e.g. using computer-generated randomisations (21, 26, 32) or consecutive

envelopes (30) or other randomisation techniques (28). In two studies, however, the

randomisation technique was not sufficiently described (29) and was limited by the

clinician’s preference and knowledge (34). The allocation concealment was explicitly

indicated only in one study (26), whilst the rest of the studies provided unclear explanation or

simply did not mention this matter. Almost all of the studies (90%) randomised the

participants at individuals level, except the one conducted by Lock et al. (27) which adopted

a cluster randomisation at practice level. Then, unlike the majority of studies which were

unable to mask the interventions from either participants or those assessed the outcomes (21,

29-32, 34); Lock et al. (27) were able to blind both of their participants and outcome

assessors. In some studies, the researchers managed to mask the outcomes assessors only (26)

or employed independent assessors who were blinded to treatment allocations (28, 33).

Intention to treat (ITT) analysis were carried out in eight publications (21, 26, 27, 29, 31-34).

One publication did not apply the ITT (30) and another one did not provide information

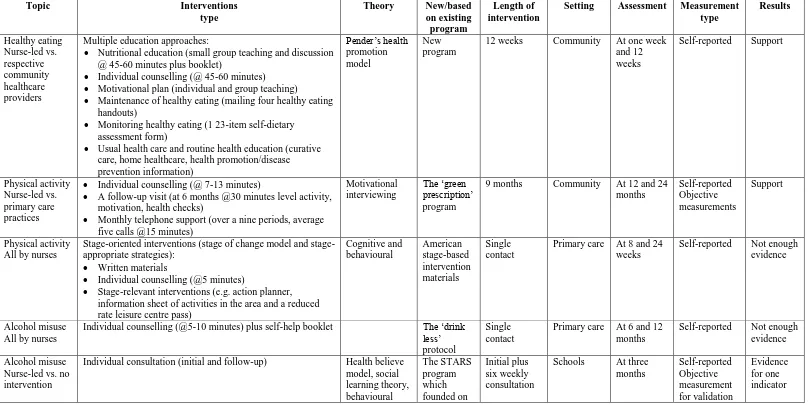

Table 1. The features of the selected publications

Topic Interventions

type

Theory New/based

on existing program

Length of intervention

Setting Assessment Measurement

type Results Healthy eating Nurse-led vs. respective community healthcare providers

Multiple education approaches:

Nutritional education (small group teaching and discussion @ 45-60 minutes plus booklet)

Individual counselling (@ 45-60 minutes)

Motivational plan (individual and group teaching)

Maintenance of healthy eating (mailing four healthy eating handouts)

Monitoring healthy eating (1 23-item self-dietary assessment form)

Usual health care and routine health education (curative care, home healthcare, health promotion/disease prevention information) Pender’s health promotion model New program

12 weeks Community At one week

and 12 weeks

Self-reported Support

Physical activity Nurse-led vs. primary care practices

Individual counselling (@ 7-13 minutes)

A follow-up visit (at 6 months @30 minutes level activity, motivation, health checks)

Monthly telephone support (over a nine periods, average five calls @15 minutes)

Motivational interviewing

The ‘green prescription’ program

9 months Community At 12 and 24

months Self-reported Objective measurements Support Physical activity All by nurses

Stage-oriented interventions (stage of change model and stage-appropriate strategies):

Written materials

Individual counselling (@5 minutes)

Stage-relevant interventions (e.g. action planner, information sheet of activities in the area and a reduced rate leisure centre pass)

Cognitive and behavioural American stage-based intervention materials Single contact

Primary care At 8 and 24 weeks

Self-reported Not enough evidence

Alcohol misuse All by nurses

Individual counselling (@5-10 minutes) plus self-help booklet The ‘drink

less’ protocol

Single contact

Primary care At 6 and 12 months

Self-reported Not enough evidence

Alcohol misuse Nurse-led vs. no intervention

Individual consultation (initial and follow-up) Health believe

model, social learning theory, behavioural The STARS program which founded on Initial plus six weekly consultation

Schools At three

self-control theory the motivational stages prevention model that posits a continuum of stages in alcohol-use habit acquisition and change Multiple focus

All by nurses

Health checks: medical history, lifestyle questionnaire, and structured dietary assessments (initial health checks @45-60 minutes; follow-up visits @10-20 minutes)

Previously developed standard health checks Initial health check Annual follow-up health checks General practices At three years Self-reported Objective measurements Support Multi focus Nurse-led vs. usual care

Individual consultation (@20 minutes) Standard

protocol

Single contact

General practices

At three and 12 months Self-reported Objective measurement for validation Support Coronary Heart Disease risk All by nurses

Individual counselling based on self-monitoring results (initial session @20 minutes)

Motivational interviewing and the stage-based concept Existing standard plus self-monitoring A 3-month protocol, including the initial and follow-up counselling General practices

At one year Self-reported Objective measurements Not enough evidence Coronary Heart Disease risk Nurse-led vs. conventional PC (primary physician)

Individual consultation (monthly for six months: initial consultation @60 minutes and follow-up session @30 minutes) Behavioural self-management, transtheoretical stages of change model New protocol

6 months At 6 months Objective

measurements Not enough evidence Coronary Heart Disease risk

Nurse-Individual counselling (initial face-to-face @60 minutes). Then monthly follow-up face-to-face @60 minutes in high level group and telephone consultation in low level group

Cognitive behavioural

New protocol

12 months General

practices

Participants

The participants in the studies represented diverse groups of the population, from young

people (31, 32) to older people (21, 26, 28, 30, 34). Three studies recruited participants from

a wide range of age groups (27, 29, 33). The interventions were mainly delivered within

primary care settings (80%) (21, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32-34) or in combination with clients’ houses

(28), and one study was at schools (31). In most studies (80%), the treatment and control

groups were comparable at entry (21, 26-30, 32, 34). In two studies (31, 33), a significant

difference was found in one aspect of the participants’ baseline characteristics; but there was

no sufficient information to determine whether or not this factor influenced the studies’

outcomes.

Interventions

The studies’ interventions varied widely, from single-focus interventions applied to target

healthy eating (28), physical activity (26, 34), and alcohol misuse (27, 31); to those applied

across several health behaviours (multiple risk factors) (29, 32); and interventions to address

CHD risk factors (21, 30, 33). The interventions ranged from a relatively simple regime that

was predominantly delivered through individual counselling or consultation with various

intensity (five to 60 minutes per each session) and diverse methods of delivery (mostly

face-to-face or in combination with telephone sessions) (27, 30-33); to more complex ones by

combining individual counselling with other interventions, e.g. small-group teaching and

discussion sessions plus usual healthcare and health education (28), health checks (26),

stage-relevant interventions (action planner and referral to leisure centres) (34), or self-monitoring

programmes (21). Only one study employed health checks as the main intervention (29).

Seven studies employed interventions that were built on the existing programmes (21, 26, 27,

29, 31, 32, 34). In three other studies, new programmes were developed base on the

standardised theories in HP, namely, Pender’s HP theory (28), behavioural self-management

and trans-theoretical stages of change model (30), and cognitive behavioural approach (33).

The interventions ranged from a single-contact intervention (27, 29, 32, 34) to those requiring

multiple contacts with clients (26, 28, 31). For studies with multiple contacts, the period of

time needed to deliver a full course of the intervention ranged from less than two months (31)

or three months (21, 28); to a longer period such as six months (30), nine months (26), and 12

months (33). A common component of all programmes was that the interventions were

treatment to their controls’ subjects, Werch, Carlson, Pappas and DiClemente (31) gave no intervention for those assigned to the control group.

Outcomes

Studies reported diverse outcomes depending on their focus interventions, including those

related to specific or multiple health behaviours and outcomes related to CHD morbidity.

Assessment methods greatly varied from relying on a self-reported survey (self-administered

or administered by the assessors) to a more objective and comprehensive measurement and

verification technique. The chosen follow-up periods were also various across the studies; the

shorter one was 12 weeks post-intervention (28) and the longest one was a three year

follow-up (29). In order to sufficiently delineate the findings and to compare studies addressing

similar outcomes, each publication will be classified into three groups that can be

demonstrated as follows:

Evidence of the effectiveness of interventions to address specific health behaviours

Healthy eating

One publication evaluating intervention for promoting healthy eating amongst the aged (≥

60 years) and their family members was identified (28). A-three month Pender’s based

nutritional-education program using multiple strategies was employed to measure its impact

on the respondents’ eating habits (food selection, preparation, and consumption). The

findings showed significantly higher scores on all indicators in intervention group at week

one and 12 weeks post-intervention. Three other studies included in this review that primarily

focused on comprehensive healthy lifestyles (29, 32) and the effect of nurse-led intervention

on CHD risk factors (33) also evaluated their participants’ dietary patterns.

Physical activity

Two RCTs focused on physical activity outcomes (26, 34). Whilst Lawton, Rose, Elley,

Dowell, Fenton and Moyes (26) specifically recruited physically-inactive women aged 40-74;

Naylor, Simmonds, Riddoch, Velleman and Turton (34) included all clients attending health

checks aged averagely 42.4. Lawton, Rose, Elley, Dowell, Fenton and Moyes (26) employed

a nine-month exercise on prescription intervention built on the existing ‘green-prescription’

program which underpinned by motivational interviewing principles. Using both

self-reported and objective measurements, the researchers measured the intervention’s primary

and Turton (34) only utilised self-reported scales to compare the effectiveness of four

variations of a single-contact staged-based intervention on participants’ stage of exercise

behaviour, exercise level, weekly physical-activity energy, and self-efficacy. Lawton, Rose,

Elley, Dowell, Fenton and Moyes (26) assessed their outcomes at 12 and 24 months

post-intervention and found that the post-intervention significantly increased physical activity and some

variables of quality of life (QoL) over two years, even there were no statistically significant

improvements in the other secondary outcomes. Naylor, Simmonds, Riddoch, Velleman and

Turton (34) did short-term evaluations at week eight and 24 post-intervention and revealed

that the stage-based interventions were not superior to other interventions. All groups

increased in their motivational readiness to exercise, without significant improvements on

physical activity levels or self-efficacy levels (34). Unequal group size at the entry and

alteration on its random assignment should be taken into consideration when interpreting

findings from this study (34). A common element of both studies (26, 34) was that the

intervention was principally delivered through a relatively brief individual counselling.

Physical activity patterns were also measured as the component of broader measurements in

other included publications (21, 29, 32).

Smoking

There was no study included in this review that specifically investigated smoking

behaviour as the primary outcome. However, it has been measured as an integral component

of studies conducted to assess the overall healthy behaviour (29, 32) and CHD risk factor

assessment (21, 30).

Alcohol misuse

Two included publications reported intervention measuring alcohol-related outcomes (27,

31). While Lock et al. (27) set a wide age interval for their included participants (aged ≥ 16

years), younger participants (aged 12.2 years ± 1.16) were recruited by Werch, Carlson,

Pappas and DiClemente (31) at schools. Although each study employed a nurse-led brief

alcohol consultation targeting individual clients based on a previously developed program,

the nature of the interventions and measurements were different. Employing a pragmatic

cluster sampling to deliver a 5-10 minute ‘drink-less’ protocol, Lock et al. (27) used a more

comprehensive assessment and standardised instruments and followed up the outcomes at six

and 12 months after the program. However, this study demonstrated no evidence that

nurse-led screening and a brief alcohol program was superior to standard intervention; but a

Pappas and DiClemente (31) only measured the outcomes up to three months after a-two

phase consultation program that was underpinned by multiple HP theories i.e. health-belief

model, social learning theory, and behavioural self-control theory. They found that there was

no significant difference between intervention and control groups, except on heavy alcohol

use (31). Alcohol behaviour related outcomes were also examined in three other studies

included in this review (29, 32, 33).

Evidence of the effectiveness of interventions applied across multiple health behaviours

There were two studies that evaluated the impact of interventions across several health

behaviours (29, 32). OXCHECK study was conducted to assess the long-term effect of a

nurse-led standardised health-check program amongst clients aged 35-64 years by measuring

self-reported outcomes and objective indicators (29). The OXCHECK study found that over a

period of three years, there were sustained positive changes in dietary pattern and cholesterol

concentrations and blood pressure (29). Walker et al. (32) recruited teenagers aged 14 or 15

employing a 20-minute HP consultation and evaluated the outcomes at three and 12 months

post-intervention. Self-reported assessments were carried out with additional objective

measurements to validate the results. Unfortunately, Walker’s et al. (32) study reported its

baseline data for intervention and control groups in a combined-single table, thus it is

difficult to highlight any differences upon the entry. Furthermore, the 12 months follow-up

results were not given in this publication (32). Except for improvements in motivation or

stage of change for diet and exercise, Walker’s et al. (32) intervention did not result in any

significant differences on other indicators. In addition, attention should have been given to

interpreting the results because there were a considerable number of non-responders

especially at 12 months in this study (32).

Evidence of the effectiveness of interventions to address CHD risk factors

Three studies investigating the effectiveness of intervention to manage CHD risk factors

were included in this review (21, 30, 33). Unlike two other studies that recruited men and

women clients aged over 50 years old with CHD risk factors, Woollard, Burke, Beilin,

Verheijden and Bulsara (33) determined a wider age interval by including hypertension

clients aged between 20 to 75 years old. In Tiessen, Smit, Broer, Gronier and van der Meer’s

study, the experimental group received a-three month additional self-monitoring program into

their existing cardiovascular risk management which underpinned by motivational

Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) formula (21). Tonstad, Alm and Sandvik (30)

administered a monthly nurse-led consultation for six months period based on behavioural

self-management and trans-theoretical stage of change theories. Here, the researchers

identified the intervention effects at baseline and six months post-intervention and then

calculated the estimated 10-year incidence of CHD using the Framingham risk model (30).

Woollard, Burke, Beilin, Verheijden and Bulsara (33) evaluated the effectiveness of three

different interventions and followed-up the effects at 12 and 18 months after intervention by

assessing physical measurements, biochemical indicators, and dietary intake. Overall,

findings from the three studies revealed that there was not enough evidence to conclude that

nurse-led interventions were more effective than CHD standard cares (21, 30, 33). However,

a lesser increase in waist circumference and reduced triglyceride concentrations was

discovered in Tonstad, Alm and Sandvik’s study (30).

DISCUSSION

Due to heterogeneities across the included primary studies’ target participants, objectives,

interventions, measurements and findings; it has not been possible to report any particular

area in greater detail. However, this report offers a general overview of the available evidence

pertaining to the effectiveness of nurse-led HP interventions in the PHC context. Several

interesting findings highlighted from this review will be discussed as follows.

In relation to the studies’ methodology, it was found that nearly all studies (90%)

employed an individual-level randomisation. Only in one study the researchers randomised

their subjects in practice level using a cluster randomisation. This is arguably necessary given

two facts. Firstly, it was impractical to randomize individuals separately within each primary

care and secondly the response to treatment of one individual may affect that of other

individuals in the same cluster (35, 36). However, given the mixed results yielded from the

primary studies and the lack of details on the randomisation method provided by some

publications, it is difficult to draw a firm conclusion as to whether it is the individual or the

cluster randomisation that was more suitable for conducting a HP RCT within the PHC

context. The decision to choose the randomisation technique should be made by considering

at least three factors i.e. the type of intervention being tested in the PHC, the level of

intervention delivery, and the risk of contamination (36).Another methodological issue in the

included studies was the difficulty to maintain the allocation concealment from the allocators.

Only one study sufficiently maintained the treatment allocations until recruitment was

Ineffective masking or blinding the interventions from studies’ participants (clinicians,

clients, and assessors) was also discovered to be a prominent problem in the majority of the

studies. Ideally, a RCT should be double blinded to the study’s participants (e.g. nurses and

clients); yet this is often difficult to achieve effectively, or may even not be feasible to do.

Alternatively, a blinded third party can be employed to assess the outcome (35, 38). Then,

when almost all of the studies analysed their data based on the ITT principle to avoid the

introduction of bias as a consequence of potentially selectively dropping clients from

previously randomised or balanced groups (35, 38); one study employed an on-treat analysis

by considering only those that participated in a full course of the intervention. This could lead

to biased treatment comparisons (35). In addition to the studies’ methodological issues

mentioned above, there was also lack of information on the validity and reliability of the

instruments used to assess the outcomes, as well as inadequate details presented in several

publications. Therefore, it is challenging for the readers to clearly interpret the studies’

findings.

The studies’ participants and contexts represented diverse groups of population and

settings within the PHC practice. This is almost similar to some earlier published reviews

which investigated the effectiveness of HP interventions within the PHC context (13, 39-41).

These findings support the notion that as a first tier of health provision, PHC offers a

universal access for all people, provides affordable and acceptable services (4), and gives

better access for its users as PHC centres are located within community settings (6). This

versatility, indeed, has placed PHC in a pivotal position to manage NCD-related lifestyles

(11).

In terms of the type of HP interventions, this review was unable to locate any studies

which employed nurse-led HP interventions at the group, community or population level.

This finding differs from those reported in the previous publications (13, 39-41). Across all

the included studies in this review, behavioural change approaches targeting individuals’

clients stood as the most frequently cited intervention. Behavioural HP strategies are

predominantly delivered through the provision of counselling or consultation and health

information to improve individuals’ HP skills (4, 7). This either results in changes to existing

unhealthy lifestyles or promotes more positive behaviour. Most studies specified the theory

underlying the interventions’ designs, which mostly stemmed from the educational, social

psychological, expectancy value, socio cognitive and decision-making theories. The key

the interventions were underpinned by the stage models of behaviour change, in particular the

trans-theoretical model. This model suggests that interventions designed to take into account

an individual’s current stage of change ‘readiness’ will be more effective and efficient than

‘one size fits all’ interventions (43).

The studies’ interventions were typically built on multiple theories of HP and required the

clinicians to employ multiple HP strategies. This is reasonable because HP itself is a holistic

concept and its integration into practice require us to take into account the role of the wider

social determinants of health (44). HP is underpinned by a social view of health, which

means that only by addressing the cultural, environmental, biological, political and economic

determinants of health can we improve the population’s health status (4). The social

determinants of health strongly relate to an individuals’ lifestyle choices and behavioural risk

factors, and these will subsequently manifest into their measurable health outcomes (4).

Unfortunately, the contribution of these aspects on HP has received very little attention in the

reviewed primary studies. This finding is identical with those found in Jepson, Harris, Platt

and Tannahill’s review (39).

The other interesting finding of this review was that in 70% of the included publications,

the outcomes were evaluated by not only relying on self-reported measurements, but also by

employing more objective and comprehensive measurement and verification techniques.

Coincidently, this same 70% of the studies also provided sufficient follow-up periods (≥ 6

months) to assess the long-term effect of the interventions; three with unequivocal evidence,

two with mixed effects, and the rest of the studies showing insufficient evidence. This is

dissimilar with Jepson, Harris, Platt and Tannahill’s review which concluded that the

majority of their included publications provided evidence in short-term effects rather than the

longer-term ones (39). Achieving a long-term, sustained effect arguably has become one of

the most significant challenges to bring about a change in people’s health behaviours.

The evidence of nurse-led HP interventions generated from the included studies varied

from outcomes which concluded that nurse-led HP interventions were effective, to those

revealing insufficient evidence to support the conclusion. Interventions that primarily

constituted of an individual counselling or consultation appeared to be the most effective

strategy to change specific health behaviours. Where two studies provided unequivocal

evidence, two showed mixed results and one publication concluded that there was not enough

evidence to support the interventions. Interventions that were most effective in changing

multiple health behaviours included those with individual counselling and health checks

conclude that nurse-led interventions were more effective compared to standard treatments.

Interestingly, although the implementation of stage-based interventions has gained its

popularity in HP research; the findings across the three evidence groups in this review

(specific, multiple, CHD morbidity) suggested that there was little evidence to support the

effectiveness of interventions underpinned by this theory. This result is congruent with a

previously reported systematic review of the effectiveness of stage-based HP interventions

addressing individual’s behavioural changes (41). Finally, since one study typically assessed

multiple outcomes, it is recommended for the reader to carefully interpret the results of the

individual publication. Likewise, ‘no significant differences’ mentioned in several studies

should not be directly inferred that nurse-led interventions were not effective in improving

PHC clients’ health behaviours. The reason for this is because in some studies, the

researchers employed nurse-led interventions in both treatment and control groups by

modifying the interventions’ elements, which resulted in positive changes across all the

groups. Thus, it may suggest that nurse-led interventions did have potential to promote

healthy behaviours amongst the PHC’ clients.

CONCLUSION

The aim of this study was to identify the effectiveness of nurse-led interventions to

promote healthy lifestyles amongst clients in the PHC context. It can be concluded that there

is some encouraging evidence that nurse-led interventions are effective in promoting healthy

lifestyles amongst the PHC clients. The interventions that appear to be most successful

include nurse-led nutritional education programs, exercise on prescription, health checks, and

nurse-led health promotion consultation. The limited number of databases being employed

for the literature search, the exclusion of non-English language and unpublished materials,

and the topic’s broad focus can be seen as the limitations of this review. A more focused

clinical question and systematic literature search is recommended for further relevant

secondary studies in order to capture more comprehensive evidence.

For those interested in investigating this topic through primary research, applying

interventions that acknowledge the interplay between people’s health and the wider social

determinants of health is advisable. Likewise, further research should be focused on

identifying the long-term effectiveness of nurse-led HP interventions by employing

standardised assessment methods. Essentially, further studies should be planned,

pp.167-8) ‘...a well designed, methodologically sound RCT evaluating an intervention

provides strong evidence of a cause-effect relation if one exists; it is therefore powerful in

changing practice to improve patient outcome, this being the ultimate goal of research on

therapeutic effectiveness’.

Findings of this review may also offer implications for the enhancement of nursing

practice and education by highlighting the need to develop approaches to foster nurses and

nursing students’ capacity to undertake their HP roles. The policy makers may also benefit

from the results by gaining a deeper understanding of the nurses’ contributions in HP practice

particularly within PHC context; then putting in place the most appropriate HP strategy to

effectively and efficiently foster the population’s health status. All of these implications are

relevant, given the international commitment to emphasis on the important role of PHC to

safeguard the health of the general population. As nurses are generally considered to be the

frontline workforce of PHC, they may affect a significant percentage of clients with their

effective HP activities, ultimately leading to a more cost-effective healthcare provision.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest noted.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The reviewer would like to acknowledge Dr. Rick Wiechula from the University of Adelaide

for his valuable supervision and assistance from the beginning of this project.

REFERENCE

1. World Health Organisation. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: World

Health Organisation, 2011.

2. World Health Organisation. Noncommunicable disease: country profiles 2011. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2011.

3. World Health Organisation. Milestones in health promotion: statements from global conferences. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2009.

4. Talbot L, Verrinder G. Health promotion in context: primary health care and the new public health movement. In: Talbot L, Verrinder G, editors. Promoting health: a primary health care approach. 4th ed. Chatswood NSW: Elsevier Australia; 2010. p. 1-34.

5. World Health Organisation. 2008-2013 Action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2009.

7. Egger G, Spark R, Donovan R. Towards better health. In: Egger G, Spark R, Donovan R, editors. Health promotion strategies and methods. 2nd ed. North Ryde NSW: McGraw-Hill Australia Pty Ltd; 2005. p. 1-25.

8. Kemppainen V, Tossavainen K, Turunen H. Nurses' roles in health promotion practice: an integrative review. Health Promotion International. 2012;27(4):1-12.

9. Kelley K, Abraham C. Health promotion for people aged over 65 years in hospitals: nurses' perceptions about their role. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2007;16(3):569-79.

10. Kendall S. How has primary health care progressed? Some observations since Alma Ata. Primary Health Care Research & Development. 2008;9(03):169-71.

11. Harris M, Lloyd J. The role of Australian primary health care in the prevention of chronic disease. Australian National Preventive Health Agency Australian Government. 2012.

12. Harris M. The role of primary health care in preventing the onset of chronic disease, with a particular focus on the lifestyle risk factors of obesity, tobacco and alcohol. Canberra: National Preventative Health Taskforce. 2008.

13. Taggart J, Williams A, Dennis S, Newall A, Shortus T, Zwar N, et al. A systematic review of interventions in primary care to improve health literacy for chronic disease behavioral risk factors. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):49. Epub 2012/06/05.

14. Noordman J, van der Weijden T, van Dulmen S. Communication-related behavior change techniques used in face-to-face lifestyle interventions in primary care: a systematic review of the literature. Patient education and counseling. 2012;89(2):227-44. Epub 2012/08/11.

15. Bosworth HB, Powers BJ, Olsen MK, McCant F, Grubber J, Smith V, et al. Home blood pressure management and improved blood pressure control: results from a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(13):1173-80. Epub 2011/07/13.

16. Orrow G, Kinmonth A-L, Sanderson S, Sutton S. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion based in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2012;344:e1389.

17. Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Dolovich L, Paterson JM, Karwalajtys T, Gierman T, et al. Improving cardiovascular health at population level: 39 community cluster randomised trial of Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP). BMJ. 2011;342:d442. Epub 2011/02/09.

18. Sakane N, Sato J, Tsushita K, Tsujii S, Kotani K, Tsuzaki K, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes in a primary healthcare setting: three-year results of lifestyle intervention in Japanese subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):40. Epub 2011/01/18.

19. Ross HM, Laws R, Reckless J, Lean M. Evaluation of the Counterweight Programme for obesity management in primary care: a starting point for continuous improvement. The British Journal of General Practice. 2008;58(553):548-54.

20. Tappenden P, Campbell F, Rawdin A, Wong R, Kalita N. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home-based, nurse-led health promotion for older people: a systematic review. Health Technology Assessment. 2012;16(20).

21. Tiessen AH, Smit AJ, Broer J, Groenier KH, van der Meer K. Randomized controlled trial on cardiovascular risk management by practice nurses supported by self-monitoring in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:90. Epub 2012/09/06.

23. Lee LL, Kuo YC, Fanaw D, Perng SJ, Juang IF. The effect of an intervention combining self-efficacy theory and pedometers on promoting physical activity among adolescents. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(7-8):914-22. Epub 2011/11/16.

24. Schadewaldt V, Schultz T. Nurse-led clinics as an effective service for cardiac patients: results from a systematic review. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2011;9(3):199-214. Epub 2011/09/03.

25. Voogdt-Pruis HR, Beusmans GH, Gorgels AP, Kester AD, Van Ree JW. Effectiveness of nurse-delivered cardiovascular risk management in primary care: a randomised trial. The British Journal of General Practice. 2010;60(570):40-6.

26. Lawton BA, Rose SB, Elley CR, Dowell AC, Fenton A, Moyes SA. Exercise on prescription for women aged 40-74 recruited through primary care: two year randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a2509. Epub 2008/12/17.

27. Lock CA, Kaner E, Heather N, Doughty J, Crawshaw A, McNamee P, et al. Effectiveness of nurse-led brief alcohol intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(4):426-39. Epub 2006/05/05.

28. Meethien N, Pothiban L, Ostwald SK, Sucamvang K, Panuthai S. Effectiveness of nutritional education in promoting healthy eating among elders in northeastern Thailand. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research. 2011;15(3):188-201.

29. OXCHECK Study Group. Effectiveness of health checks conducted by nurses in primary care: final results of the OXCHECK study. Imperial Cancer Research Fund OXCHECK Study Group. BMJ. 1995;310(6987):1099-104. Epub 1995/04/29.

30. Tonstad S, Alm CS, Sandvik E. Effect of nurse counselling on metabolic risk factors in patients with mild hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. European journal of cardiovascular nursing : journal of the Working Group on Cardiovascular Nursing of the European Society of Cardiology. 2007;6(2):160-4. Epub 2006/08/18.

31. Werch CE, Carlson JM, Pappas DM, DiClemente CC. Brief nurse consultations for preventing alcohol use among urban school youth. Journal of School Health. 1996;66(9):335-8.

32. Walker Z, Townsend J, Oakley L, Donovan C, Smith H, Hurst Z, et al. Health promotion for adolescents in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ: British Medical Journal (International Edition). 2002;325(7363):524-7.

33. Woollard J, Burke V, Beilin LJ, Verheijden M, Bulsara MK. Effects of a general practice-based intervention on diet, body mass index and blood lipids in patients at cardiovascular risk. Journal of cardiovascular risk. 2003;10(1):31-40. Epub 2003/02/06.

34. Naylor PJ, Simmonds G, Riddoch C, Velleman G, Turton P. Comparison of stage-matched and unmatched interventions to promote exercise behaviour in the primary care setting. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(5):653-66. Epub 1999/10/06.

35. Petrie A, Sabin C. Medical statistics at glance. 3rd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

36. Elley C, Kerse N, Chondros P. Randomised trials - cluster versus individual randomisation: Primary Care Alliance for Clinical Trials (PACT) network. Australian Family Physician. 2004;33(9):759 -63.

37. Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995;273:408-12.

38. Kendall JM. Designing a research project: randomised controlled trials and their principles. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2003;20(2):164-8.

40. Wilhelmsson S, Lindberg M. Prevention and health promotion and evidence-based fields of nursing - a literature review. Int J Nurs Pract. 2007;13(4):254-65. Epub 2007/07/21.

41. Riemsma R, Pattenden J, Bridle C, Sowden AJ, Mather L, Watt I, et al. A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions based on a stages-of-change approach to promote individual behaviour change in health care settings. Health Technology Assessment. 2002;6(24):1-242.

42. Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River NJ.: Prentice Hall; 2006.

43. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Trans-theoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 1982;19:276-88.