Darja Aepli

S

TATE

-S

OCIETY

R

ELATIONS AND

I

NTERNAL

M

IGRATION

:

H

OW

P

RACTICES OF

S

TATE AND

S

OCIETY

R

EPRODUCE

T

HE

GEO 511

Master Thesis

Department of Geography, University of Zurich

S

TATE

-S

OCIETY

R

ELATIONS AND

I

NTERNAL

M

IGRATION

:

H

OW

P

RACTICES OF

S

TATE AND

S

OCIETY

R

EPRODUCE THE

R

EGISTRATION

S

YSTEM IN

O

SH

,

K

YRGYZSTAN

.

31 January 2014

Darja Aepli

08-701-856

Submitted to Prof. Dr. Norman Backhaus

This study was conducted within the framework of the Swiss National Centre of

Competence in Research (NCCR) North–South: Research Partnerships for Mitigating

Syndromes of Global Change. The NCCR North-South is co-funded by the Swiss

National Science Foundation and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation.

Cover Picture Centre of the City of Osh (own photo)

i

Acknowledgement

This study was conducted in the frame of the NCCR North-South research programme on “migration and development”, in the thematic field of “livelihood, institutions, conflicts”. I want to thank to NCCR North-South for their support and for enabling me this research.

Further I want to thank my supervisors Craig Hatcher and PD Dr. Susan Thieme for their valuable

inputs, feedbacks and in general their helpful support during the whole process of the study.

Prof. Dr. Norman Backhaus for his appraisal.

In Kyrgyzstan, I want to thank Bermet Ubaidillaeva and Mukadas Tashieva for their research

assistance in Osh: They did an important contribution to the success of the research with their

great work.

In Osh, I also want to thank to Asel Botpayeva for her hospitability and for the many interesting

discussions which helped me to better understand Kyrgyz politics, history and culture.

Special thanks to Daulet Tinibaev for his valuable support in many ways.

Finally I want to thank to all the interview partners, which gave me a comprehensive insight to the

registration system in Osh. This research would not have been possible without their openness and

their willing to share their experiences. Great thanks to the Advocacy Centre for Human Rights and

the Ferghana Valley Lawyers without Borders for their cooperativeness and their willing to give

ii

Summary

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, migration became a widespread phenomenon in

Kyrgyzstan, while a high percentage of the migrants are internal migrants who move from rural to

urban areas within the borders of the country. As in the majority of the countries, people who

move from one place to another have to register in the new place of residence, in order to inform

the state about their staying. The registration system of Kyrgyzstan goes back to the Propiska

system which was applied in the Soviet Union. This system was officially abandoned after

Kyrgyzstan became an independent Republic in 1991 and was replaced through a

notification-based system which complies with the Guidelines on population registration of OSCE. However,

hegemonic practice seems to differ from the given law, as the registration procedure is mostly

depending on local self-governance bodies and their local provisions. There are evidences from

Bishkek that the registration system remains restrictive as it is difficult to register and the lack of

registration results in the limitation of basic services and rights.

The kind of implementation of the registration system in other parts of the country remains largely

unexplored. The aim of this research is it to contribute to the knowledge on the implementation of

the registration system in Kyrgyzstan. As the south of Kyrgyzstan is socio-economic, ethnically and

politically different from the north, this research focus on Osh, which is one of two main attracting

points for internal migrants in the south, and there are evidences that there is a huge amount of

internal migrants living there without registration. The conducted empirical research should provide

insight to the local requirements to get registered, the problems occurring with it, and the

problems internal migrants encounter without registration. These insights provide the basis for the

research questions how state and society practices reproduce each other through the registration

system, what kind of registration system they reproduce and what are the consequences of being

registered or not being registered for internal migrants. In order to answer these questions, two

months of field research were conducted in Osh, the biggest city of the south of Kyrgyzstan, where

principally interviews with internal migrants were conducted.

The empirical material was analysed and discussed on the hand of approaches to state-society

relations of Migdal, Mitchell, Gupta and Foucault. Migdal’s approach was basically used to identify

the practices of state and of society and their intertwined relationships as an analytical entity to

reveal the reproduction of one another in the context of the registration system. Further, the analysis in this master thesis followed Gupta’s recommendation to focus on the lower level of bureaucracy in order to detect how state influences everyday practices of society. To reveal the

power generation on the micro-level, the approaches of Mitchell and Foucault were applied as those

approaches provide insight how practices of both state and society generate the disciplinary power of the state, while they shouldn’t be analysed distinct of each other, moreover the reproduction of the line between state and society should be included into analysis. Since Weber’s state definition and his concept of bureaucracy forms the starting point for most state-society relation approaches,

his work was also important and were included into the analysis of this thesis.

iii agreements, which would be a precondition for registration. Since most internal migrants come to

Osh out of pressing economic reasons, it can be assumed that fewest of them are able to purchase

an own property from beginning and consequently most internal migrants live in Osh as tenants at

first. As a consequence of the impossibility to fulfil the requirements to register, those tenants

often register in their relatives place. This practice is even suggested to them by the officials from

the passport offices. In that way, wrong information about the place of residence of people is

reproduced, additional to the lacking information about the place of residence through the absence of registration in Osh in the first place. Thus the registration system doesn’t fulfil its duties according to the guidelines of OSCE to provide information about the staying of the residents.

A further challenge next to the high requirements to get registered is the lacking communication

between the passport office and internal migrants. On the one hand, communication is rather

intransparent as it is only provided orally, and on the other hand many internal migrants don’t

know that they can find information about the registration procedure in the passport office. Again

other internal migrants don’t even think about the registration at all since it doesn’t have any

importance to them.

Through those restrictions which make it impossible for most internal migrants to register in Osh

from beginning, a part of society is reproduced which doesn’t enjoy full access to basic services and

civic rights. The precondition to have a registration in the place of residence in order to get access to basic services isn’t given by the law and even contradicts to it; moreover it is reproduced by everyday practices of state and society. However, the results show that indeed there are some

handicaps for people without registration to receive those basic services, but most of them manage

to get access without registration, particularly through a spravka from the Domkom or through bribery, while most interviewees didn’t consider bribery as a big handicap. Others just travelled back to their place of origin in order to access basic services. Due to the short distance between

Osh and the original village of most of the interviewed migrants, this travel wasn’t considered to be

iv

2.1.2 State-Society Concepts Based on the Weberian State Definition... 6

Joel Migdal ... 6

2.1.2.1 Strong and Weak States ... 8

2.1.2.2 2.1.3 Alternative Approaches Beyond the Weberian State Definition ... 9

Akhil Gupta: Challenged Bureaucracy and the Local Perspective ... 10

2.1.3.1 Timothy Mitchell: The State as a Set of Structural Effects ... 11

2.1.3.2 Michel Foucault: Disciplinary Power, Panopticism and Governmentality ... 12

2.1.3.3 2.1.4 Summary of the Concepts ... 15

2.1.5 The Role of the State in (Internal) Migration ... 16

2.1.6 Registration Systems Restricting Internal Migration ... 18

3.2.2 Registration System in Kyrgyzstan (State of the Art) ... 31

v 5.2 Practices of State Actors which Reproduce the Registration System... 48

5.2.1 Requirements and Challenges of the Registration System ... 49

Required Documents to Get Registered in Osh ... 49

5.2.1.1 Challenging Requirements ... 50

5.2.1.2 How State Reproduce Society and the Registration System through Challenging 5.2.1.3 Requirements ... 55

5.2.2 Information about the Registration System ... 56

Passport Offices ... 56

5.2.2.1 Communication and Information on Registration through the Passport Office .. 57

5.2.2.2 Other Sources of Information and Support ... 59

5.2.2.3 Knowledge of Internal Migrants about the Registration System ... 61

5.2.2.4 Reproduction of Society through the Provision of Information ... 62

5.2.2.5 5.2.3 The Registration System and Panopticism ... 63

Legal Consequences of Living without Registration ... 64

5.2.3.1 Importance of Compliance with the Law for Internal Migrants ... 65

5.2.3.2 5.2.4 The Limitations of Access to Basic Services and Rights ... 67

Access to School and Kindergarten ... 67 Limitations of Rights and Access to Basic Services and the Implications for 5.2.4.9 State-Society Relations ... 77

5.3 The Practices of Society which Reproduce the Registration System ... 79

vi

Bribery to Get Registered ... 83

5.3.2.3 5.3.3 Strategies without Registration ... 85

Getting Access to Basic Services and Rights through the Domkom spravka... 85

5.3.3.1 Getting Access to Rights and Basic Services through Bribery ... 86

5.3.3.2 Going Back to the Village to Get Services and Rights ... 86

5.3.3.3 Pragmatic Reasons not to Register in Osh ... 87

5.3.3.4 6 Conclusions ... 91

7 Reference List ... 95

8 Apprendix ... 101

8.1 Guideline for Interviews with Labour Migrants in Osh ... 101

8.2 Examples of Guidelines for Expert Interviews ... 103

8.2.1 Guideline for the First of Two Interviews with Ferghana Valley Lawyers without Borders ... 103

vii

Index of Tables

Table 1: Osh Oblast migration fluxes (in Persons) ...44

Index of Figures

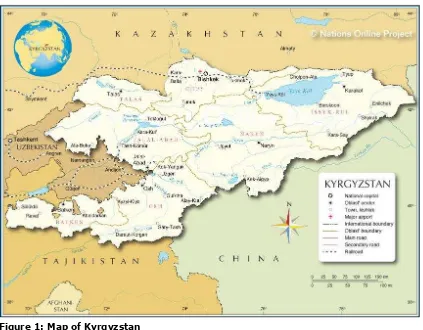

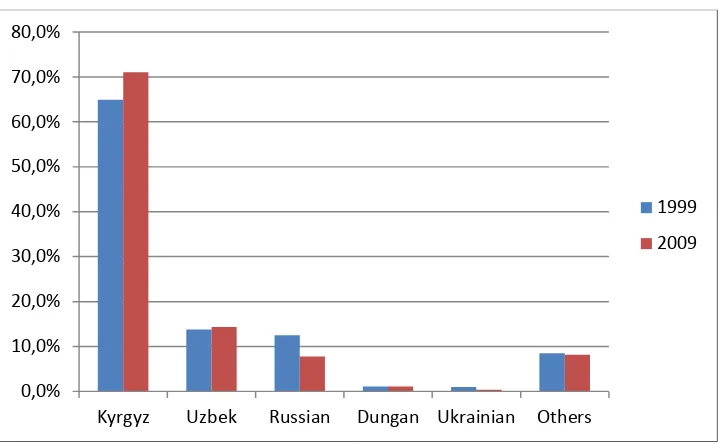

Figure 1: Map of Kyrgyzstan ...23Figure 2: Ethnicities in Kyrgyzstan ...25

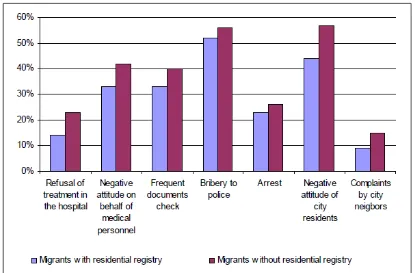

Figure 3: Discrimination of migrants without registration ...32

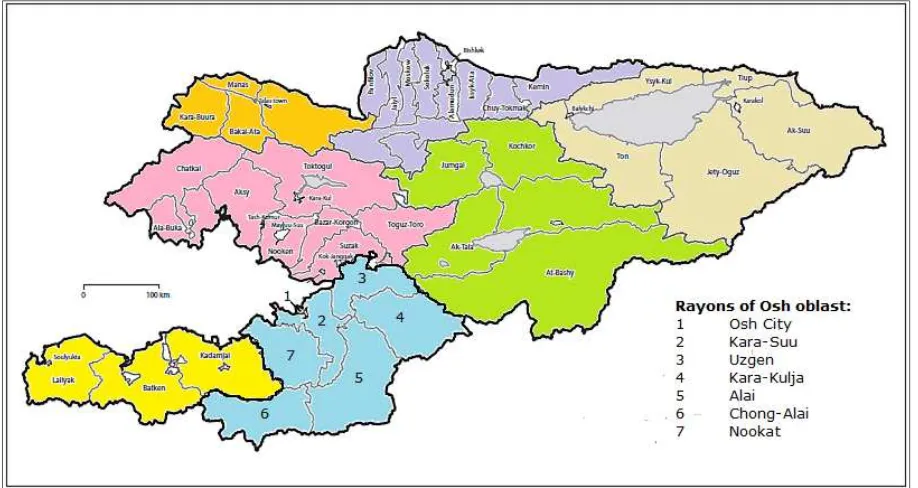

Figure 4: Administrative oblasts and rayons in Kyrgyzstan ...43

Index of Photographs

Photo 1: The White House, Bishkek's political centre ... 27Photo 2: Memorial of the revolution in 2010 ... 27

Photo 3: Main street in the centre of Osh... 44

Photo 4: Bazar of Osh ... 44

Photo 5: State-owned school dormitory in Osh, inhabited by internal migrants ... 47

Photo 6: Privatized dormitory in Osh ... 47

Photo 7: Shared bathroom in a dormitory ... 47

Photo 8: Shared kitchen in a dormitory ... 47

Photo 9: Room in a dormitory ... 47

Photo 10: Former datcha settlement inhabited by internal migrants ... 48

Photo 11: Little datcha hut with annexe ... 48

Photo 12: Example of a domovaya kniga (property document) ... 54

Photo 13: Passport office in Osh ... 57

Photo 14: Table in the passport office with templates of forms ... 57

viii

Abbreviations

CIA Central Intelligence Agency

CIS Commonwealth of Independent States

FTI Foundation for Tolerance International

FVLWB Ferghana Valley Lawyers Without Borders

GDP Gross Domestic Product

HDI Human Development Index

IOM International Organization for Migration

NCCR National Centre of Competence in Research

OSCE Organisation for Security and Co-operation Europe

PPP Purchasing Power Parity

UN United Nations

UNDP United Nations Development Program

UNECE United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

USSR Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

WB World Bank

Glossary

Datcha (russ.) Small holiday or weekend cottage, mostly located in

settlements on the edge of the cities in Russia and Post-

Soviet countries

Domkom (russ.) Shortage for Domovyi Komitet, also territorial soviet.

A person who is elected to be responsible for the

maintenance of the housing area, and to record the

inhabitants of the housing area

Domovaya Kniga (russ,) Property ownership document which is needed to register

the property in the Gos register

Dormitory State owned temporal living places mainly for

ix Gos register (russ.) State agency for registration of rights to immovable

property

Militia Conventional denomination for police in Kyrgyzstan

Novostroika (russ.) New settlements in the outskirts of Bishkek, inhabited by

internal migrants. While some of them are legalized, others

still remain illegal

Oblast (russ.) Province; highest territorial administrative unit.

Kyrgyzstan is divided into 7 Oblasts.

Propiska (russ.) The Russian word Propiska can be translated as registration

or registration permit. It designates a restrictive registration

system established and implemented in the USSR.

Rayon (russ.) District; next smaller administrative territorial unit after

oblast. Kyrgyzstan is divided into 43 rayons.

Som Kyrgyz currency; 54.76 KGS = 1 CHF (January 2013)

1

1

Introduction

The vast majority of people who migrate from one place to another do this within the borders of a

country. This kind of migration within one nation-state is called internal migration (UNDP, 2009,

p.21). Despite the quantitative relevance of this type of migration, the focus of contemporary

research lies more on international migration, while internal migration remains rather neglected

(Laczko, 2008, p.9). The role of the State on internal migration can be either to enforce, to restrict

or to regulate migration (Massey 1999, p.307). Internal migration is recorded in countries around

the world with the help of the registration system, which should enable the state to plan its

infrastructure according to the numbers of people living in an area, and to contact its citizens

(OSCE, 2009). Most countries apply a notification-based registration system, where the citizen is

obliged to notify the state about his or her place of residency, which usually is an unproblematic

and banal procedure (Schaible, 2001, p.350). However, in some countries – mainly those with a

Post-socialist context – the state intends to regulate and even limit internal migration through

restrictive registration systems like the Hukou household registration system in China or the

Propiska registration system in USSR (Hatcher, 2011, p.2). Those registration systems are

institution of the state, which are constantly reproduced by practices of both state and society

practices. On the hand of the theoretical frameworks of Migdal, Foucault and Mitchell and Gupta –

who provide different approaches to state-society relations – the reproduction through those

practices can be analysed. According to those theorists, state and society are intertwined and

constantly reproduce each other through their practices. State power shouldn’t be seen as

something distinct which exists self-evidently. Moreover it is reproduced through practices of state

and society and their interactions. Especially Foucault, Mitchell and Gupta emphasize the

importance to analyse those practices and interaction on the micro-level in order to understand the

character of state-society relations and how power is emerging.

Kyrgyzstan is a country with a high migration rate, while a big part of migration takes place within

the borders of the country (Thieme, 2012). The most prevalent direction of internal migration flows

is from the south to Bishkek, followed by the Northern Oblasts Chui and Yssik-kul, but there are

also migration flows from rural to urban areas within the south (BMP, 2011, p.69). Most prevalent

place of origin of the migrants is the south of Kyrgyzstan (Thieme, 2012, p.5). Despite a lot of

research on migration in Kyrgyzstan focus on emigration mainly to the neighbouring countries

Russia and Kazakhstan (e.g. Ruget and Usmanalieva, 2010), there is some research conducted on

internal migration as well, yet most of it focus on migration to Bishkek (e.g. Flynn and

Kosmarskaya, 2012; Hatcher, 2011; Nasritdinov, Zhumakadyr and Asanalieva, 2012; Azimov and

Azimov, 2009), while migration within the South remains largely unexplored.

As a former Soviet country, Kyrgyzstan’s registration system is a legacy of the former Propiska

registration system of the USSR. Even if the Propiska registration system was officially abandoned after independence and the “Law on internal migration” prescribe a notification-based registration system, there are evidences that the practice of registration fairly contradicts to that law, since it is

regulated more through local self-governance bodies than through that law (Azimov and Azimov,

2

differs from the law (e.g. Azimov and Azimov 2009, Hatcher, 2011), but there is hardly any

research on the registration system in other parts of the country. As the north and the south of the

country are ethnical, socio-economic and politically different (Ryabkov, 2008), and the registration

system is regulated locally, it can be assumed that the implementation differs between the

northern and the southern part of Kyrgyzstan. Since Osh together with Jalalabat is the main

attracting site for internal migration within the South (BMP, 2011, p.69), this research should

dismantle the implementation of the registration system in Osh. There are a remarkable number of

internal migrants living in Osh without a city registration, according to some estimations this

phenomenon concerns the half of the population in Osh (Akmatov, 2011).

The aim of this research is to identify state-society practices and their relations to each other which

are reproducing the registration system, which is characterized by the widespread absent of

registration.

Research Questions:

(1) How do state and society practices reproduce each other in relation to the registration

system in Osh?

(2) What kind of registration system do they reproduce through their practices?

(3) What are the consequences of being registered or being not registered for internal

migrants?

State in the context of this thesis always refers to the state actors who are dealing with the

registration system. This includes the officials of local self-government bodies, police deputies,

politicians and people working in state institutions like teachers and doctors. The registration

system as an institution of the state is constituted by the practices of those state actors. However,

these practices of state stand in an intertwined relation to the practices of society. Society in the

context of the registration system in this research refers to the internal migrants moving to Osh.

Their everyday practices in the context of the registration system reproduce the practices of state

and therefore the registration system as well. Moreover state and society practices continuously

reproduce each other. Reproduction in this research thus refers to the influence of practices of

both state and society on the registration system, which is built and constituted through these

practices.

The state of the art on the implementation of the registration system in Bishkek builds the starting

point for this research. Interviews mainly conducted with internal migrants in Osh within a

framework of an empirical field study provide insight to the implementation of the registration

system in Osh. On the hand of these insights, it will be revealed how state and society practices

reproduce this registration system, which kind of registration system is reproduced. Since the

registration system in Osh is characterized by a widespread absence of registration, the

consequences of living in Osh without registration should be evaluated as well.

After the introduction to the theoretical background and the context of research, the results of the

field study will be analysed and discussed, where the first part focus on practices of state and the

second part on practices of society, i.e. internal migrants. However, on account of their intertwined

3 entirely distinct to each other. Therefore, in the state part the author consistently will point out

how the practices are reproduced by society as well as how they reproduce society by themselves,

and naturally she will do the same in the society part. However, the focus of analysis will lie on the

5

2

Theoretical Background

2.1

Theories on State-Society Reproduction

In this chapter the appropriate approaches to identify the reproduction of state through society

should be identified and presented. Theories on the way how society and state transform and

reproduce each other have their origin in the state-society relation discourse. This discourse can be

divided into two strands of fundamental concepts: On the one hand there are the statist

approaches where state-society relations are analysed with a focus on state itself. In contrast,

there are approaches which explore state-society relations with a focus on interactions and

interdependency between state and society. (Sellers, 2011, p.124)

2.1.1

Weberian Conception of State

Independent from the focus of the approach, most conceptions of state in state-society relation

scholars are based on the Weberian conception of state (Kohli, 2002 cited in Sellers, 2011, p.124).

Max Weber defines state through the following terms:

“State is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory. Note that ‘territory’ is one of the characteristics of the state.” (Weber, 1946, p.13)

Even if there are other organizations which have the right to use physical power, they are only

legitimated to do so with the permission of the state.

“State is a relation of men dominating men, a relation supported by means of legitimate (i.e. considered to be legitimateд violence.” (Weber, 1946, p.14)

His definition of state is based on Hobbes interpretation of Leviathan. If this order of a state ruling a society wouldn’t exist, there would be anarchy (Corbridge, 2008, p.107).

Bureaucracy is another essential concept of Max Weber which other state analysts often refer to. It

can be applied for the state as well as for economic entities, but for this thesis only the meaning

for state should be pointed out. Bureaucracy is the main concept of the way how modern states

perform, where state is defined as a bureaucratic apparatus which follows certain principles: (1) “There is the principle of official jurisdictional areas, which are generally ordered by rules, that is, by laws or administrative regulations” (Weber, 1968, p.49). This principle refers to the right manner of distribution of official duties, and that these duties have to be fulfilled by qualified

employees. (2) “The principle of office hierarchy and of channels of appeal” (ibid.) means that a lower level of hierarchy is always supervised by a higher one. The next principle says that (3) “The management of the modern office is based upon written documents.” (Weber, 1968, p.50) Through this principle, the objectivity and impersonality should be guaranteed. On this place, Weber also

6

usually presupposes thorough training in a field of specialization” (ibid.). The occupation of an

official becomes a profession which has to be learned and (рд “When the office is fully developed, official activity demands the full working capacity of the official” (ibid.). Official business is no longer a secondary activity but becomes the main occupation for the respective official. The last

principle which Weber specifies says that (6) “the management of the office follows general rules,

which are more or less stable, more or less exhaustive, and which can be learned. Knowledge of

these rules represents a special technical expertise which the officials possess” (ibid.).

All these principles have the goal to separate the private from the public sphere on different levels:

On the one hand through the spatial separation between the working place and the official’s private

place, and on the other hand through universal rules according to which official work is made to a

profession, where the official doesn’t have to decide anymore on the basis of his own weighing up

as there are rules which he can follow to for every decision. Thus these rules contribute to an

impersonal behaviour of state officials, what means that they have to treat anyone in the same

way, independent of ethnicity, gender, etc. An external person must be treated in the same way

like a family member. However, this model is only an ideal type while in reality these boundaries

often become blurred and the model can only be converged as near as possible. Weber’s definition

of state which is performed according to bureaucracy principles became highly popular in the time

after 1945 and is still important for contemporary approaches on state-society relations.

(Corbridge, 2008, p.108)

2.1.2

State-Society Concepts Based on the Weberian State Definition

State-society relation approaches which are based on the Weberian definition of state re-emerged

in state-society discourses in the mid1970s through the call to “bring the state back in” (e.g.

Skocpol 1985; Krasner 1984). They mostly presume a clear distinction or even a separation

between state and society, and they are still hegemonic in the contemporary discourse on

state-society relations (Sellers, 2011, p.126). However, there are also approaches based on the

Weberian state definition which focus on the interaction between state and society. One of the

main approaches taking account of these interactions – especially in developing countries – is Joel

Migdal with his state-in-society approach (Sellers, 2011, p.129).

Joel Migdal 2.1.2.1

State Conception of Migdal

Even if it’s said that Migdal’s approach is also grounded on Weber’s state conception (Sellers, 2011, p.129), he offers a further development of the latter:

“The state is a field of power, marked by the use and threat of violence and shaped by the image of a coherent, controlling organization in a territory, which is a

7 The two terms “image” and “practice” are highlighted in his definition, they are the elements which form the state, and they can overlap, reinforce, contradict or destruct each other. With “Images”

he refers to the imaginations people have from state, how people perceive the state. The origins of

all the imaginations of the state can be located in the emergence of states in North-West Europe in

the fifteenth century. This image of state became dominant and was spread all over the world. This

fundamental image of states creates two kinds of boundaries which define a state: First the

bureaucratized state. These boundaries separate state from society, and because state is a unique

representation of its population, he argues that state is not only separated, but even elevated over

society. (Migdal, 2001, pp.15-17)

The second key attribute of Migdal’s state definition, “practices”, refers to the practices performed

by state actors and agencies as well as actors outside of the state, or even of both of them

combined. Either they reinforce, neutralize or weaken the image of state with its social and

territorial boundaries. Examples for practices which underpin the territorial boundaries of the state

are passports, border markers, armies, official maps etc., as well as certain ceremonies or the

spatial restriction of official state work to definite places like federal buildings confirm the

separation between state and society and even the elevation of state. However, corrupt and

criminal practices neutralize or weaken the image of state with its territorial and public-private

boundaries. In contrast to the images of the state, which imply one singular morality, there is a multiplicity of various practices and they don’t always reproduce the image of the state how it should be. For example, Public-private boundaries can become weak through officials who do

private business in their official working place, or through more complex situations like relations

between criminal groups and the influential state actors. These kinds of practices challenge the

sharp distinction between state as a rule maker and society as a recipient of those rules and these

boundaries becomes blurred. Moreover, the territorial boundaries can be affected by practices of

groups which refuse these boundaries like nomadic groups or minorities which claim for an own

state. (Migdal, 2001, pp.18-20)

Shortly said, Migdal argues that even if state and society are two distinct entities which are not

only separated from each other, moreover state is elevated over society, there are some practices

of state and of society which challenge this clear distinction and make the boundary between public

and private becoming blurred. The image gives the state a clear dimension of a unified

organization which can be seen like a single actor which performs in a certain way. However, the

practices of actors from inside and outside of state, which determine if this image is enforced or

deconstructed, are fragmented and loosely connected, with an unclear distinction from each other

(Migdal, 2001, p.22). This challenging of boundaries between state and society in his approach is

8

Migdal’s State-in-Society Approach

Migdal’s state-in-society model is built on this dual definition of state through image and practice.

Only through this duality and the interplay between those, processes of domination can be

understood (Migdal, 2001, p.22). Through the transformative power of these practices, a

continuous struggle for social control and domination between state and society forces takes place

(Migdal, 1993, p.26). He criticizes that these struggles for domination between state and society

are often neglected by state-centred scholars, and that the prevalence of the state as a unitary actor isn’t questioned. (Migdal, 1993, p.8)

As the state on the one hand forms society through its actions and on the other hand is formed by

the society it is embedded in (Lambach, 2004, p.3), object of analyse in research which applies

Migdal’s state-in-society approach should be the processes of interactions between groups with one

another as well as between ruling groups and the subjects they want to influence or to control.

Migdal states that:

“like any other group or organization, the state is constructed and reconstructed,

invented and reinvented, through its interaction as a whole and of its parts with

others. It is not a fixed entity; it organization, goals, means, partners, and operative

rules change as it allies with and opposes others inside and outside its territory. The state continually morphs.” (Migdal, 2001, p.23)

This means, to understand how state is reproduced, the practices of state and non-state actors and

the interactions between them have to be examined.

Migdal’s state-in-society approach especially addresses the explanation of power relations in

developing countries or the ex-colonized world. His approach further develops the hitherto

predominant Eurocentric perspective to the state, in which the existence of the nation-state is

taken for granted. He criticizes the neglecting of the fact that many ex-colonized states aren’t

historically grown. But this fact is essential for evaluating states of the developing world.

(Lambach, 2004, p.3)

Strong and Weak States 2.1.2.2

If a state can be considered as a strong or a weak state largely depends on its relations to society

(Luong, 2004, p.271). Even if Migdal didn’t develop the state-in-society approach yet, he already

discussed the struggle for domination or social control in one of his previous works “strong societies and weak states” in 1989, where he focus on the capability of developing states to perform social control. These capabilities…

“…include the capacities to penetrate society, regulate social relationships, extract resources, and appropriate or use resources in determined ways. Strong states are

9 Thereby, social penetration which is part of the struggle for domination can occur in four forms: In

the first form, the state manages to transform society actors fully, e.g. with the tool of forced

migration or displacement. So the domination of state over society is strong. In the second form,

the state is able to incorporate in existing social forces. In the third form social forces are

incorporating the state, and the last form is that state fails in all of those attempts. With all of

these presented forms, state domination declines while the power of social forces increases. While

in the first form state power is strong, power of society overhang in the last form. (Migdal, 1993,

pp.25-26)

According to Smith (2005 cited in Ruget and Usmanalieva, 2007, p.442), weak states are “unable

to maintain political order and security, to enforce laws, implement policies and to deliver services.” However, a state can be weak in one of these obligations, while in others it can be successful and strong. As a consequence of the weakness of a state, Ruget and Usmanalieva argue that people have low expectations on state and that “citizens are less likely to perform their duties, to trust the regime and to have a sense of loyalty towards their nation state.” (Ruget and Usmanalieva, 2007, p.443) In other words, a weak state reproduces a society which isn’t law

-abiding but strongly self-relying, which brings forward that society builds its own structures where

it can rely on.

Ruget and Usmanalieva (2007, p.442) state that if a state is weak, the boundaries between state

and society can become blurred. This assumption matches to Migdal’s theory, as discussed above,

that the image of the state with its territorial and social boundaries is determined by practise, and

if practice is challenging state power, boundaries between public and private can be blurred. However, in the other way round, blurred boundaries don’t compelling have to signify weak states. Luong (2004) illustrates that point with his explanations of state-society relations during the Soviet

Times: There he writes that state-society boundaries where blurred while the state was strong and

society was weak. While Migdal and Ruget and Usmanalieva emphasize more that blurring

boundaries are a sign that the obligations of state are contested by the mixing of private and

public, Luong shows that the infiltration of state in non-state spheres can also strengthen the state,

e.g. through the control and infiltration of NGOs. Furthermore, he also talks about non-state actors which can’t be clearly assigned neither to state nor to society. As an example he refers to the role of Mahalla committees in Uzbekistan which are composed by citizens which are independent social

actors, but in the same time they are empowered as local leaders by the Uzbek state. So they represent both society as well as state and therefore can be seen as “mediators” between state and society. He doesn’t compelling see the strength of the state challenged through these non-state actors. For studying contemporary state-society relations in Central Asia, he argues, it is crucial to

take into account the Soviet legacy of these blurred state-society relations and the societal

weakness (Luong, 2004, p.274).

2.1.3

Alternative Approaches Beyond the Weberian State Definition

There is another discourse strand where the Weberian conception of state and the strong

10

therefore shouldn’t be transferred to all of the countries. This critique is also supported by other analysts like Sellers (2011), who also doesn’t consider the Weberian state model as accurate to

describe the contemporary political world, especially in developing countries.

Mitchell’s (1991, p.82) critique to Weber’s state definition is that it’s rather a characterization than a definition of state and doesn’t give information about the contours of state. It is still open where

the boundaries of state can be drawn. In his approach of state as “a set of structural effects”, he developed an own definition of state. This definition is based on Foucault’s concept of disciplinary power, where society continuously reproduces the power of the state.

The mentioned analysts criticized the dominating state-centred discourse as too imprecise to cope

with contemporary state-society relations. Thus they developed these dichotomist state-society

conceptions to more sophisticated approaches which more emphasize the intertwined relationship

between state and society and their mutual reproduction and take into question their distinction in

the first place. In the following chapters, some of these approaches will be presented in detail as

they are important concepts to answer the research question how state and society reproduce the

registration system.

Akhil Gupta: Challenged Bureaucracy and the Local Perspective 2.1.3.1

In his research on corruption in a small town in North-India, Gupta identified state-society

boundaries according to Weber’s model of bureaucracy as blurred. Albeit he analysed the ways how

these boundaries become blurred, he takes into question the model of those boundaries between

state and society at the first place. He states that this model is based on the Western state model and therefore shouldn’t be applied to any other places without being questioned. It doesn’t mean that he fully abandoned Weber’s concept of Bureaucracy, but he pleads for applying it with caution and not to taken for granted the boundaries between state and society. (Gupta, 1995, p.214)

Gupta also pleads for a local perspective. Onto the time he wrote his paper, ethnographic research

had a strongly large-scale focus on politics while the lower levels were rather neglected. He states

that it were the everyday practices of officials which give insight on the effects of politics on the

daily lives of rural people. It is the local, lower level of bureaucracy where people engage with the

state through making contact with officials in different concerns. Therefore in those local spaces

state-society interactions emerge. The way how these interactions are performed builds a crucial

part of the image of people from the state. Thus it is important to focus on this local level in order

to understand interactions between state and society and their implications for the imagination of

state. (Gupta, 1995, p.212)

Gupta further illustrates the linkages between this local levels and the state as a transnational

actor: The state is constituted by a “complex set of spatially intersecting representations and practices” (Gupta, 1995, p.213), which means that both large- and small scale practices as well as their interactions form the image of the state. Out of that reason, it is important to include all the

levels into analysis of the state. Even if the research object is the state as a transnational actor,

11 These arguments show that Gupta doesn’t consider state as a unitary actor as many statist analysts see the state. Moreover he pleads for the importance to take into account the different

levels of bureaucracy to achieve a comprehensive analyse of the state. (Gupta, 1995, p.214)

Timothy Mitchell: The State as a Set of Structural Effects 2.1.3.2

Timothy Mitchell criticizes the statist state-society conceptions after the call for “bring the state back in”. The definition of the concept “state” were too narrow as it became reduced to a “subjective system of decision making” (Mitchell, 1991, p.78). However, his main critique point (Mitchell, 1999, p.169) on statist state-society conceptions concerns the distinction between state

and society: State is always perceived as a distinct entity which stands outside or is even opposed

to the larger entity called society, and analyses are limited to the question on the degree of independence of these two entities from each other. This doesn’t embrace the reality where these boundaries are often blurred (Mitchell, 1991, p.89).

Further he takes into question the distinction between state as something abstract, conceptual in

opposition to society as something concrete, empirical and he criticized that in the hitherto state-society discourse after the “bring back the state in” call in the 1970s this distinction hasn’t been taken into question (Mitchell, 1991, pp.81-82). According to him, state and society stand in an

intertwined relationship to each other and both of them are abstractions in relation to concrete

structures (Mitchell, 1999, p. 185).

However, Mitchell argues that those boundaries – even if they are blurred – are still important and shouldn’t be downplayed. He reveals this argument in the first point of his approach where he defines the state as “a set of structural effects” (Mitchell, 1991, p.95). As an example of blurred

state-society boundaries he refers to relationships between governments and economic exponents,

which can act on the same level, if economic actors, which belong to the private sphere, begin to

codetermine in politics, i.e. in the public sphere. These relations and with it the permeability of

these boundaries have a certain political importance for the state. (Mitchell, 1991, p.89) Therefore

this example illustrates that the boundaries between state and society can still be powerful, even if

they are uncertain. On the base of these findings, he suggests to accept the elusiveness of a

state-society boundary as a characteristic, as the nature of the state itself, instead of seeing it as a

conceptual problem of the state definition. Therefore the definitions of state-society relations

should include these uncertain distinctions and examine the political processes which produce

(elusive) state-society distinctions. Instead of seeing the boundary between state and society as a

boundary between two discrete entities, it should be seen as a line existing within the system of

institutional mechanism. (Mitchell, 1991, p.78)

Second he argues that state should be seen not only as an abstraction of ideas, moreover it is

constantly represented and reproduced in everyday life. Through architecture, language, passports

etc. state can also manifest itself as something material, as a concrete realm. If state is only

perceived as an abstract ideological construct, all these manifestations of state are excluded of the

concept state, and therefore he argues to include the material dimension to the concept of state.

(Mitchell, 1991, p.81) In his third point he pleads for abandoning the narrow concept of state as a

12

and again contributes to the perception of state as something abstract versus society as something

concrete. Fourth, state more persists as an effect of different processes like spatial organization,

temporal arrangement, functional specification, supervision and surveillance. Modern politics isn’t

performed anymore in the way that the on one side (state) policies are formulated which are later

applied on the other side (society). While Migdal sees this state-society boundary challenged

through practices like corruption, Mitchell goes further and rather than seeing this distinction as

something self-evident which can be challenged, he sees it as a process of continuous production

and reproduction of the line between state and society. (Mitchell, 1991, p.95)

Fifth, all these mentioned processes create a sum of structural effects which are building the state,

while state isn’t a discrete entity outside of society, but more it becomes a distinct dimension of

structure, framework, codification, planning and intentionality. The distinctions between abstract

and concrete are constructed from the social processes which build the state. (Mitchell, 1991, p.95)

Mitchell also uses Foucault’s approach of disciplinary power to underpin his argument that state doesn’t stand outside from society. He argues that the modern way how states exercise power works on a micro-level within society, and isn’t applied from outside (Mitchell, 1991, p.92).

However, he further develops Foucault’s conception with his arguments that in the same time as

disciplinary power is origin from within the society, it also becomes an exterior force, for example

with a military apparatus emerging out of individual discipline which becomes greater than only the

sum of its parts, like an emerging machine (Mitchell, 1991, p.93).

On the one hand, this emerged machine becomes something separately existing, next to society, but in the same time it’s impossible that it exists independent of its individuals. It’s in the same time a part of society because it consists of individuals as well as something more than just a part

of the society, a new entity which emerged out of society and became something by itself. The

institutions are not the same like the practice of individuals, they are more, but they are emerging

out of it and later also can stand as an own entity in opposite to it. This demonstrates the unclear

distinction between state and society. The two entities indeed exist as own entities and even can stand in opposite of each other, but they can’t be fully separated because they depend on each other. (Mitchell, 1991, p.93) Because of this constitution of the state, he calls state “a set of

structural effects” (Mitchell, 1991, p. 94), a set of effects, consisting of practices of individuals

where the result is more than only the sum of it. Therefore, state as well as society is something

abstract as well as something concrete. Concrete actions are building the abstract elements which

the state is composed of.

Michel Foucault is a further fundamental analyst on whose theories an own scholar was built: The

scholar of the Foucauldians. The Foucauldians focus strongly on the far-reaching power of state

through surveillance and social reach (McNay, 1994 cited in Corbridge, 2008, p.110). Foucault’s

13 Western image of states which begun to form themselves in direction to modern states in the 18th

and 19th century, but considering the exportation of the Western image of states during the

colonization, and now continuing with the globalization, it can be assumed that it also becomes

meaningful for other countries. (Mitchell, 1991, p.92).

As Mitchell explains Foucault’s concept, the power achieved from state isn’t an authoritative power

emerging from outside of the state. If state is perceived as a freestanding agent, which is ruling

society through making law and orders, the way how power functions in the contemporary world can’t be fully explained. In the modern sate, power doesn’t derive only from state; it also has to be created from society. Power emerges on a micro-level through the practice of society members. It

derives from discipline which is permeating every kind of life of individuals. Through discipline,

complex processes are split in particular movements, every activity is split in elementary

sequences which are easy to conduct and in total build the complex process. This discipline is

applied in all the institutions, for example school, army, prisons, hospitals, government offices and even commercial establishments. This applied discipline doesn’t compelling constrain individuals, moreover they are produced by this discipline. Through this way of behaviour - through disciplinary

power – institutions are produced and are able to work, and a modern individual is produced.

(Mitchell, 1991, pp.92-93)

On this point there is also a connection to Weber’s bureaucracy, since bureaucracy through all its

regulations according to Weber’s principles also has a disciplinary effect, which again enforce the domination of the state and its social control. Thus, if bureaucracy isn’t performed according to its principles and state-society boundaries become blurred, the disciplinary power effect of

bureaucracy and therefore also the domination of the state diminishes (Brown, 1995, p.200).

However, what is the motivation that people act disciplinary, why are they doing so? In his book “Discipline and punish”, Foucault (1977) illustrates clearly how disciplinary power works. Pre-condition for the development of disciplinary power were the changings in the system of

punishment. In the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century, a shift became apparent

in Western Europe, away from public punishment ceremonies like quartering, which made

punishment to a public spectacle. First, punishment begun to disappear from the eyes of the public,

it became something invisible, what let the imaginations about it become more and more abstract.

Second, punishment moved away from causing physical pain especially through torture and

towards to deprivation of condemned people from their freedom to dispose over their own body,

e.g. through imprisonment, forced labour etc. One impressive example for this principle of

deprivation instead of causing pain is the situation of execution in due to death penalty: The

condemned will be deprived from everything, even from his life, but he gets tranquillizers in order

to not feel pain. Further, the meaning of punishment more became a technique to correct the

behaviour of people and was not so much anymore just led through the pure desire to punish and

do harm to the condemned person. Consequently, a new morality of punishing emerged. (Foucault,

1977, pp.8-12)

With this shift in punishment away from violence was the basis for the emergence of a power which

14

disciplinary power plays the model of the panopticon, which illustrated the way how disciplinary

power works. The panopticon is a metaphor for perfect supervision and surveillance and concerns a

geometrical construction in a prison designed by Jeremy Bentham, where from a central tower

every part of the prison can be supervised. According to Foucault, society should be supervised in

compliance with this ideal. As more society converges to this ideal of surveillance and supervision,

as more efficient the disciplinary power effect becomes. Through this supervision, people are

constantly aware about their visibility and take punishment as a logical consequence of their

actions if they are doing something which contradicts the law. Therefore, the metaphor of the

panopticon stands for a system of social control through which disciplinary power can be achieved.

This model of supervision and surveillance is called Panopticism. (Hannah, 1997, pp.171-73)

The terms of supervision and surveillance were already encountered in this chapter in relation to the second principle of Weber’s bureaucracy: The principle of office hierarchy, where the supervision of lower hierarchies through higher ones is one precondition for the functioning of bureaucracy. Therefore disciplinary power isn’t only reproduced by bureaucracy, but through the inherence of Panopticism in the principles of bureaucracy, it is in turn also reproduced by itself

through disciplinary power.

On the scale of a nation-state, Foucault calls this system of social control “Governmentality”

(Hannah, 1997, pp.171-73). The concept “Governmentality” denominates a specific way how state

rules society:

“Government is defined as a right manner of disposing things […] to an end which is convenient for each of the things that are to be governed.” (Foucault, 1978, p.95)

Due to the growth of population since the industrialization, it became more difficult for state to

exercise its power only in an authoritarian way. Therefore, tasks of the state to exercise power

were not simply to control society, but moreover to care about the welfare of all of its members. Thus state didn’t anymore gain power only through direct control, but moreover through create conditions which guarantee the welfare of its population. It means that the economy came into

play in political practice. Newly state had to provide good economic conditions in order to

guarantee the welfare of its population. In that way, state was not anymore fully separated from

society, it became a part of it as state-members became also a part of the economy. (Foucault,

1978, p.92)

Considering Foucault’s general contribution to state theorizing, he emphasized the variety of

practices and institutions which are exercising state power, while many of them are not mandatory

state-actors. Further, in contrast to many other state theorists which are involved with analysing

the sovereignty of the state and power exercising in the summits of the state apparatus, he pleads

for a bottom-up approach where the starting point of analysis are the diffuse power relations of

state and non-state actors on the local and regional scale, what he called as micro-power (Jessop,

15

2.1.4

Summary of the Concepts

Similar to Migdal’s (2001) approach of a state which is defined by images and practices, Foucault

(1977; 1978) also talks about the relative definition of state. He argues that state is reproduced

and redefined by the tactics of the government, which are the counterpart of “practice” in Migdal’s

approach. However, his focus is more on the micro-level of power generation. In that point he

agrees with Gupta (1995), who also emphasizes the importance to include the regional level of

politics for state analyses. The competences and limits of a state are negotiated by tactics of

Governmentality on the large scale which generate disciplinary power from the large scale until the

smallest scale of detail. Therefore, he argues, the importance of state is often overrated (Foucault,

1991 cited in Migdal, 2001, p.18). With overrating the importance of state, Foucault addresses the

too strong focus on the large-scale entities of state and the neglecting of the level of detail, where

disciplinary power emerges.

Mitchell’s (1991) second point according to which the abstract state consists of concrete manifestations of state like passports, borders, languages etc. complies with Migdal’s (2001)

theory that practices reinforce the image of state. Gupta (1995) also addresses these

manifestations, but emphasize that it is the local level where society and state really meat together

and state become visible and therefore concrete. For Migdal (2001), those practices which

reproduce the state can be clearly separated into practices of society and the state, while Mitchell

(1991; 1999) sees the practices both as actions of individuals and therefore part of society as well

as part of state because an apparatus is built out of their individual practices which are based on

discipline. Therefore he argues that the unclear distinction between state and society must be part

of the definition of state, instead of continuing to try to define the borders of the state. The

practices create parts of the state like institutions, so they are part of it, but in the same time they

can also stand apart of it as individuals.

Mitchell (1991) criticizes or complements Foucault’s (1977) concept of “disciplinary power”. He emphasizes that discipline doesn’t always have to be a source of power for the state, as it can also counteract to state. As an example he argues that resistance movements often have their own

military which achieves its power also through discipline, or they are using state institutions like

schools which are built on disciplinary, but their disciplinary practices are addressed against the

power of state (Mitchell, 1991, p.93). This can also be explained by the practices mentioned by

Migdal (2001) which can either enforce or weaken the image and therefore the power of the state.

The comparison between the illustrated approaches shows the similarities between them. They all

focus on the reproduction and transformation mechanisms between state and society, and they all

agree with the conception that the image of state is constituted by the practices of state and of

society. Therefore, the approaches of Gupta, Mitchell and Foucault shouldn’t stand in opposite of

16

2.1.5

The Role of the State in (Internal) Migration

Most literature on the role of the state in migration concerns the international migration. In account

of the growth of the North-South migration in the last decades, political debates on migration

mostly refer to migration in that certain direction (Laczko, 2008, p.9) Generally, states in migration

research are analytically distinct in receiving, developed countries and in sending developing

countries. (Massey, 1999, p.303)

While the focus in migration studies for a long time lied on receiving states in the north, recent

studies pay more attention on the impacts of migration in the south, especially on the effect of

remittances (IOM, 2013, p.21). Further there is growing attention on South-South migration as it

becomes acknowledged as the major migration flow next to South-North migration which was long

the major object of research (IOM, 2013, p.55). However, migration within the borders of a nation

state – internal migration – remains underexamined. Despite the estimated high quantitative

significance of that migration type it is hardly mentioned in the recent World Migration Report

(IOM, 2013). The processes of internal migration were more analysed in the terms of urbanization

or population distribution. The lack of data on internal migration also challenges the research on it.

The exact extent of internal migration is unknown, but most probably it exceeds the extent of

international migration by numbers (Laczko, 2008, p.9). According to a conservative estimation by

the UNDP (2009, p.1) there are 740 Million internal migrants worldwide which would be four times

more than international migrants.

The difference between Internal and international migration is defined by the relation to the border

of a nation state. While international migration crosses borders of nation states, internal migration

takes place within the borders of a state. The distinction between internal and international

migration can become blurred if the borders of nation-states are transformed. For example “27

million persons became international migrants upon the break-up of the Soviet Union whereas previously they were internal migrants” (Skeldon, 2008, p.29). In that example the definition of the type of migrants changed while the movement of the people remained the same. On the other

hand, open borders blur the distinction between internal and international migration as well, e.g.

with Schengen in Europe. If a migrant crosses open borders between two nation-states, is he still

an international migrant? Moreover internal and international migration aren’t always distinct of

each other as they can be parts of the same process. For example, international migration can

leave gaps in the place of origin which are filled by internal migrants (Skeldon, 2008, p.37).

Because of these interlinkages and the blurred boundary between internal and international, these

two kinds of migration shouldn’t be analysed isolated and partially can be analysed by common

approaches. Because they are interlinked to each other and the difference between them is more

defined through the borders of the nation-state than through the characteristics of the process,

internal migration should be more included in migration studies. (King and Skeldon, 2010, p.1640)

Arguments are mostly only formulated for international migration, but they might be valid for

internal migration as well. Massey (1999, p.307) argues that immigration policies can “encourage, discourage or otherwise regulate the flow of migrants”. Considering that states also have to handle internal migration in a certain way, these are also the parameters for policy on internal migration.

17 international migration, this might be not the case on the political theorisation of migration (King

and Skeldon, 2010, p.1641). Adequately, state treats internal migration differently from

international migration, therefore it has to be analysed separately. The mentioned parameters

indeed can be applied for internal migration as well, but they might differ from the way state

handles international migration.

States usually record internal migration through a registration system. Though, according to the OSCE (2009, p.20) “the population-registration system should facilitate freedom of movement and avoid managing population movements by putting limits on the free choice of place of residence.” The majority of countries perform a notification-based registration system, which should not

restrict the movement of people but enable the state to contact its citizens, and to gather data on

population size and movements for planning purposes. If the numbers and the demographic data

of inhabitants are known, the distribution of resources and infrastructure like schools, hospitals etc.

can be allocated (Hatcher, 2011, p.6). Notification-based registration systems are usually

complying with those OSCE guidelines and other Conventions like the UN human rights, since they don’t restrict the freedom of movement or residence. The process of registration is usually unproblematic and possible to conduct for everyone, and most notably no basic services and rights

are linked to that registration (Schaible, 2001, p.350). For example in Switzerland, the laws on

registration are regulated on a cantonal level. Someone who changes his place of residence needs

to deregister in the place of origin and register in the place of destination within 14 days. (S)he has

to bring the documents which are deposited in the municipal office in the place of origin to the

municipal office of place of destination (Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, 2006). There are even

countries without any mandatory registration system, e.g. the United Kingdom (Hatcher, 2011,

p.5). In that way, internal migration is neither restricted nor enforced. Moreover state has an

overview about the movement and the place of residence of its citizens.

However there are some countries – mainly those with a post-socialist background (Hatcher, 2011,

p.2) – with a more restrictive registration system which might discourage people to migrate within

their country. As Deshingkar and Grimm (2005 cited in Laczko, 2008, p.10) show in their report,

internal migration seems to have a mainly negative connotation for the state, even if there are

numbers of evidences that it can contribute to the welfare of a country. They see following reasons

for that:

“…that internal migration is an “administrative and legislative nightmare”: it crosses physical and departmental boundaries confusing rigid institutions which are not used

to cooperating with each other. The authors argue that by not acknowledging the vast

role played by internal migrants in driving agricultural and industrial growth,

governments escape the responsibility of providing basic services to millions of poor

people who are currently bearing the costs of moving labour to locations where it is most needed.” (Deshingkar and Grimm 2005 cited in Laczko, 2008, p.10)

This negative connotation in turn can state a reason for a restrictive handling of internal migration.

In the following section, two prominent examples for a restrictive registration system should be

introduced: The Hukou system in China which is – although alleviated – still performed, and the