O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

‘‘You Need to Stop Talking About This!’’:

Verbal Rumination and the Costs of Social

Support

Tamara Afifi1, Walid Afifi1, Anne F. Merrill1, Amanda Denes2, & Sharde

Davis1

1 Department of Communication, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106-4020, USA 2 Department of Communication Sciences, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269, USA

This study examined whether the type of support individuals receive when they are verbally ruminating affects their cognitive rumination (brooding), anxiety, and relationship satisfaction; 233 young adults were randomly assigned to be the subject, 233 others the confederate. The confederate was trained to provide ‘‘good support’’ or ‘‘poor support’’ to the subject who talked about a topic he/she had been verbally ruminating about recently. When individuals verbally ruminated and received poor support, they became more anxious and dissatisfied with the friendship. When individuals received good support, they were more satisfied with their friendship, but their anxiety was not significantly reduced. In addition, verbal rumination was directly associated with more brooding after the conversation, regardless of the type of support provided.

doi:10.1111/hcre.12012

When people experience a stressful event and cannot stop thinking about it, they frequently turn to friends for support (Rime, Philippot, Boca, & Mesquita, 1992). Although social support generally makes people feel better, talking about a stressor with others does not necessarily relieve one’s distress and can sometimes make it worse (Holmstrom, Burleson, & Jones, 2005; Xu & Burleson, 2001). People are not always supportive when someone comes to them with a problem, particularly when this person talks about the same problem incessantly (Stroebe, Zech, Stoebe, & Abakoumkin, 2005). Friends may not want to hear about the problem anymore, may not know what to say, or may criticize the person for still thinking about it. Even if support providers have good intentions, they might not be able to help the person stop brooding about the stressor and could magnify his/her anxiety and ruminative tendencies.

Research has shown that when people verbally ruminate, it can adversely affect their social networks if their stress spills over onto others (see Saxbe & Repetti, 2010) or they communicate social depression cues that make it difficult for people to be around them (e.g., Conway et al., 2011). Little is known, however, about how

social support affects the individuals who are verbally ruminating and whether the support reduces their brooding. Brooding rumination involves focusing passively and repetitively on one’s negative emotions and problems, their causes and consequences, and self-evaluations related to them (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). Verbal rumination is similar to brooding rumination, except that it focuses on repetitive talk—continually talking about a problem and its potential consequences, negative emotions surrounding the problem, and one’s role in it. These two processes often occur concurrently (Tait & Silver, 1989), but tend to be analyzed separately. Yet, the successful management of one most likely affects the other (see also Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999).

Social support may act as an important moderator of the impact of verbal rumination on brooding, as well as mental and relational health. If people offer support that is validating, reassuring, and helps the support seeker reframe the problem about which they are ruminating, it could minimize the endless cycle of brooding and anxiety they are experiencing while also enhancing their relationship with the support provider. To the contrary, when people receive poor support when they are verbally ruminating, it likely exacerbates their anxiety and brooding and strains the relationship. We test this argument in the context of young adult friendships. Young adults face numerous stressors, such as financial challenges, risky behaviors, and career aspirations, for the first time when they live independently from their parents. These stressors may be sources of worry that become chronic topics of discussion with close friends.

Verbal rumination and brooding rumination

Most of the work on self-disclosure has found that disclosing personal information is health promoting. While there are numerous reasons why people disclose, much of the research on self-disclosure suggests that people feel better after they disclose because it is cathartic (see Afifi, Caughlin, & Afifi, 2007 for a review; Derlega, Winstead, Greene, Serovich & Elwood, 2004). For example, Pennebaker’s work (Pennebaker, 1989; 1995) shows that people often experience physical health benefits when they disclose stressful events.

Research on the fever model (Stiles, 1987; Stiles, Shuster, & Harrigan, 1992) also demonstrates that when people disclose what they are ruminating about, disclosure tends to reduce their anxiety and ruminative tendencies. Moreover, self-disclosure helps build and maintain relationships because people develop emotional bonds through the sharing of private information (see Altman & Taylor, 1973; Pearce & Cronen, 1980; Petronio, 1991, 2002; Wheeless, 1976). As the basic tenants of social penetration theory (Altman & Taylor, 1973) suggest, people move from disclosing non-intimate information (or ‘‘breadth’’) to intimate information (or ‘‘depth’’) as their relationships progress, which fosters greater psychological closeness between them.

depend heavily on the response (expected or actual) from the person to whom one is disclosing (Checton & Greene, 2012; Derlega, Winstead and Folk-Barron, 2000; Derlega et al., 2004, 2010; Petronio, 1991, 2000, 2002; Petronio, Reeder, Hecht, & Ros-Mendoza, 1996). In general, when people perceive others as trusting and expect them to respond positively to their disclosure, the benefits of disclosing increase and the costs decrease (Afifi & Steuber, 2009; Petronio, 2002; Wheeless & Grotz, 1977). Whether the disclosure of a stressor is beneficial depends upon numerous factors, including the validating nature of the response (Afifi, Olson, & Armstrong, 2005; Greene, 2009) and the extent to which the support enables the person to make sense of a stressful event (Kelly & Macready, 2009).

Verbal rumination is also different than simply disclosing. Because verbal rumi-nation focuses on repeated disclosures of personal problems and negative emotions, it could have a more harmful effect on one’s mental health than self-disclosure in general. For example, parents’ negative disclosures about the other parent to their child tend to be associated with anxiety in both the parent and the child (Afifi & McManus, 2010; Denes, Afifi, Granger, Joseph, & Aldeis, in press). Afifi and McManus (2010) found that parents’ negative disclosures about the other parent were associated with closer parent–child relationships, but increased anxiety in the child. Even though disclosures, perhaps in some cases regardless of their valence, can foster psychological closeness between individuals, they can simultaneously harm people’s mental health if the negativity spills over onto others or begins to affect one’s own psychological well-being. If these negative disclosures occur excessively, they could create even greater anxiety.

Most of the recent research on verbal rumination focuses on corumination or two people excessively discussing problems with each other (Rose, 2002), rather than verbal rumination where one person discloses his/her problems to another. In particular, that research examines corumination in adolescence in an attempt to explain why girls tend to have more anxiety and depressive symptoms than boys and how these effects materialize in friendships over time (e.g., Schwartz-Mette & Rose, 2012; Stone, Uhrlass, & Gibb, 2010). Research shows that girls report being more satisfied with their friendships than boys, which should protect against emotional problems, but ironically, they simultaneously report being more anxious and depressed (Starr & Davila, 2009). The mutual disclosure likely brings the friends closer emotionally, but also fosters anxiety due to the preoccupation with negative emotions (Rose, 2002). Because self-disclosure is more common in female friendships than male friendships, researchers argue that females tend to experience the heightened benefits and consequences of corumination (Smith & Rose, 2011). It is worth noting, however, that, the research supporting such a sex effect is mixed, with an equal amount of research finding no sex differences (see Hankin, Stone, & Wright, 2010; Smith & Rose, 2011; Stone, Hankin, Gibb, & Abela, 2011).

internalizing problems in adolescents (6th to 10th graders) predicted greater coru-mination with friends over time and that corucoru-mination, in turn, predicated greater internalizing problems. These bidirectional effects escalated in severity through ado-lescence. A couple of studies have also found effects for corumination in young adulthood (Byrd-Craven, Geary, Rose, & Ponzi, 2008; Calmes & Roberts, 2008). For instance, Byrd-Craven et al. (2008) discovered that when college-age female friends co-ruminated, their cortisol increased. These studies provide evidence that excessively discussing problems in young adult friendships is linked to internalizing problems.

Unlike with corumination, verbal rumination typically involves one person disclosing problems and negative emotions while the other provides support. The type of support individuals receive when they are verbally ruminating could affect their relationship and their anxiety and brooding. The research on corumination assumes that people receive comparable levels of support, despite this often not being the case. Social support might provide a powerful theoretical explanation for how and why verbal rumination affects anxiety and satisfaction, as well as brooding, irrespective of biological sex.

Theoretical connections to social support

When people become preoccupied with a stressor, they often talk about it with others to relieve their distress. The extent to which that social support is effective for individuals who are verbally ruminating, however, is still unclear. Social support tends to buffer the ill effects of stress on people’s mental and physical health (see Afifi, Granger, Denes, Joseph, & Aldeis, 2011; Albrecht & Goldsmith, 2003; Burleson, 2009). According to the stress buffering hypothesis, better quality support and larger social support networks minimize the effect of stress on people’s health (Cohen & Wills, 1985) and should make people feel better when they are verbally ruminating. However, research on verbal rumination and traumas, natural disasters, contagion effects, and depression provides evidence of both stress buffering and stress deterioration (see Conway et al., 2011; Stone et al., 2010). People may be able to provide good support initially, but are unable to sustain it because their emotional resources have been drained (e.g., Afifi, Afifi, & Merrill, 2013). People might deny social support to friends who talk about the same problem excessively because they should be ‘‘over it’’ by now. Support providers can also become stressed themselves as a result of the discloser’s stress spilling over onto them through repeated, negative talks. Or, sometimes individuals provide poor support if they feel like the person deserved his/her stress (Kaniasty & Norris, 1993).

‘‘rumination and anxiety can create a reciprocally determinative cycle in which each tends to promote and prolong the other’’ (Zawadzki et al., 2012, p. 2).

Social support could help disrupt this negative cycle. For example, Nolen-Hoeksema and Davis (1999) found that high ruminators reported less distress over time if they had dense social networks, received good support, and felt comfortable talking about their stress. In contrast, high ruminators reported more distress over time if their social support network was critical of them, disagreed with the decisions they made, or had high conflict. Even though the authors did not examine verbal rumination, specifically, they were able to show that when people confide in others about their stress, social support can serve an important moderating function.

But, what constitutes ‘‘good’’ support when someone is verbally ruminating? Support providers who use high person-centered (HPC) messages with friends who are verbally ruminating should reduce their friends’ anxiety and brooding because of the comfort and assurance provided. HPC messages explicitly validate, comfort, contextualize, and elaborate on the distressed person’s feelings and emotions about the stressor (Burleson, 1982, 2008; Burleson & MacGeorge, 2002; Holmstrom et al., 2005; Jones & Guerrero, 2001). HPC messages also involve esteem support where the support provider attempts to enhance how the support receiver feels about him or herself (Holmstrom & Burleson, 2011). This is in contrast to low-person centered (LPC) messages that tend to deny the feelings of the distressed person (Burleson, 1982, 2008). Support that is more person-centered has been associated with greater emotional improvement compared to lower person-centered messages and could provide a more hopeful interpretation of stressful situations (Jones, 2004; Jones & Guerrero, 2001; Jones & Wirtz, 2006) and reduce rumination. Bippus (2000, 2001), for example, found that the skillfulness of the comforting behaviors provided (i.e., less negativity, taking the perspective of the other person, problem solving, and reframing) was predictive of less rumination, more positive mood and greater empowerment.

Indeed, social support that helps people who are verbally ruminating reframe their stressor could minimize the cascade of anxiety and intrusive thoughts they experience. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) theory of stress and coping, events become stressful when people perceive that the demands of the situation outweigh their resources or ability to cope (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). When a stressor occurs, people make primary appraisals about the extent of the stress and they make secondary appraisals where they weigh their available coping options and decide what to do about it (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

verbally ruminating to appraise the stressor differently and provide alternative coping strategies—allowing them to sooth their anxiety and brooding. In so doing, they probably also feel better about their relationship with the person who is providing the support.

In addition to verbal HPC messages and reframing of the stressor, good social support should also be nonverbally immediate (Guerrero, Jones & Burgoon, 2000; Jones & Guerrero, 2001). As Jones and Guerrero argue, even though most research on person-centered messages focuses on the verbal messages, verbal comforting messages, and nonverbal immediacy cues, such as head nods, touch, eye contact, paralanguage, and body orientation, occur simultaneously and support receivers interpret them as such. As such, the verbal and nonverbal messages should be used in conjunction with one another when assessing the effectiveness of social support. As Miller (2007) has also found with her work on compassionate communication in the workplace, communicating compassion includes verbal and nonverbal indicators of noticing another, connecting, and responding. Taken together, social support that is high person centered, encourages positive reframing of the stressor, and is nonverbally immediate (e.g., involved, pleasant, encouraging), should provide an optimal, ‘‘safe’’ environment to disclose.

In contrast, when people are verbally ruminating and they are provided with poor support, this combination likely magnifies their anxiety and brooding. Some aspects of Burleson’s low person-centered messages (see Burleson, 1982, 2008) where the support provider dismisses an individual’s irrational thoughts (e.g., ‘‘that person is not worth your time. . .just stop thinking about it’’) could actually reduce brooding (see Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). Messages that are more disconfirming of the individual, however, should have an adverse effect on ruminative tendencies. Discon-firming messages that criticize individuals’ choices, blame them for their own stress, or invalidate their feelings and perspectives likely reinforce their negative view of the self. The disconfirming messages may exacerbate their beliefs that they are the source of the problem, increasing their anxiety and dissatisfaction with the relationship. For example, a series of studies by McLaren, Priem, and Solomon (McLaren & Solomon, 2008; McLaren, Solomon, & Priem, 2011; Priem, McLaren, & Solomon, 2010; Priem & Solomon, 2011) has shown that hurtful messages that are disconfirming are physiologically stressful and relationally distancing. Likewise, immediacy cues where a person appears to be distracted, uninvolved, and lacking in expected levels of intimacy are anxiety-producing for support receivers (Guerrero et al., 2000).

In general, how one’s anxiety and relationship satisfaction are influenced as a result of verbally ruminating should depend upon the type of support received when one is verbally ruminating. When individuals are verbally ruminating and receive poor support, regardless of gender, it should increase one’s anxiety and brooding and decrease relationship satisfaction. The opposite effect should occur when good support is provided. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

ruminating will increase one’s satisfaction whereas poor support will decrease one’s satisfaction.

H2: Social support will moderate the association between verbal rumination and (H2a) state anxiety and (H2b) brooding rumination, such that being provided with good support when verbally ruminating will decrease one’s anxiety and brooding rumination, whereas poor support will increase one’s anxiety and brooding rumination.

Verbal rumination and brooding rumination likely work together to affect neg-atively people’s anxiety and relationship satisfaction. Individuals’ verbal rumination should be especially anxiety-producing when they are provided with poor support and they brood about it afterward. When people brood about what transpired in their interaction with their friend, they likely become even more anxious because they have had the time to mull about their problem and their inability to solve it. They are also probably more dissatisfied with their friendship because they have brooded about the fact that their friend was disconfirming toward them and their situation. Consequently, a third hypothesis is presented:

H3: The degree to which one’s verbal rumination affects one’s (H3a) anxiety and (H3b) satisfaction with the friendship will depend on the support that is provided

(good/poor) and the extent of the brooding rumination afterward. Being provided with poor support when one verbally ruminates and engaging in higher levels of brooding rumination afterward should increase anxiety and relationship dissatisfaction, whereas being provided with good support and engaging in lower levels of brooding

rumination afterward should decrease anxiety and increase relationship satisfaction.

Method

Participants

Two hundred thirty-one young adults and one of their friends came to the laboratory on one occasion. The average age of the participants was 19.84 (range=18 to 26).

Most of the participants were female (n=159 or 68%; males=72 or 31%). When

taking the friend into account, there were 112 (48%) female–female dyads, 35 (15%) male–male dyads, and 86 (37%) female–male dyads. The sample was a diverse representation of White (n=81; 35%), Latino (n=46 or 20%), Black (n=61 or

26%), Asian (n=30 or 13%) and ‘‘other’’ (n=15 or 6%) ethnicities. Eighty-one

(35%) of the participants were first year undergraduates, 61 (26%) were sophomores, 55 (24%) were juniors, 30 (13%) were seniors, two were in graduate school, and four were not in college.

Procedures

told that they could not be dating this person and that the friendship needed to be platonic. Before arriving at the laboratory, one of the friends was randomly assigned to be the subject (support recipient) and the other a confederate (support provider). At the same time, the confederate was randomly assigned to the ‘‘good support’’ (n=107) or ‘‘poor support’’ (n=124) condition (see below).

To enhance the believability of the study, both the subject and the confederate were briefly informed about what would happen in the study (including that their interaction would be videotaped) and provided topic listing sheets. They were asked to write down up to three topics they currently found stressful, that they could not seem to get off their mind, and that they could not stop talking about. They were also told that they should be topics that they already talked about with their friend who came with them to the laboratory, but that the topics could not involve their friend or their relationship. After each topic, they also completed four Likert-type items that asked how much they currently mulled over the topic and the extent to which they brought it up as a topic of conversation. The researcher also informed the participants that they would complete all of the surveys in different rooms to ensure privacy. The researcher chose the topic that the subject verbally ruminated about the most as the topic for the friends to discuss (but informed the subject that it was randomly chosen). The researcher refrained from choosing topics that were deemed particularly sensitive (e.g., severe illness, death, body image).

After being placed in separate rooms, the subject began completing the preinter-action survey while the confederate was informed of the true purpose of the study and trained to provide either good or poor support. Good and poor support were based on Burleson’s (1982) person-centered messages (HPC messages for the good-support condition and low person-centered messages for the poor-support condition) and Jones and Guerrero’s (Guerrero et al., 2000; Jones & Guerrero, 2001) nonverbal immediacy cues.

The confederates were trained to maintain eye contact, have their body oriented toward their friend, use head nods, listen actively, be involved in the conversation (e.g., vocal utterances that emphasize listening), generally reciprocate nonverbal behaviors, and avoid distractions. In addition, in terms of the verbal channel, the confederates were trained to ask their friend how he/she was feeling (e.g., ‘‘how are you feeling about what happened?’’) and then validate those feelings (e.g., ‘‘I’m so sorry that you experienced that’’) and provide comfort, probe for more information or details about the stressor, elaborate in detail on the situation and the friend’s feelings (e.g., ‘‘I know how deeply you cared for each other and how much time you spent together, that must be really painful’’), and eventually try to help the friend cognitively reframe the problem. They were also asked not to talk about their own problems, but to keep the focus on their friend’s problem.

of their friend’s discussion of his/her problem, to be disconfirming of their friend’s situation and ideas, and to blame him/her for being the source of the stress. Emphasis was placed on engaging in these behaviors while appearing natural and maintaining behavioral plausibility. Confederates in this condition were trained to act as they typically would for the first minute, then to engage in some of the aforementioned nonverbal behaviors, and gradually introduce the verbally disconfirming behaviors that were low person centered, invalidated the person’s feelings, and blamed the person for his/her stress.

Because the researcher knew the topic of the discussion and the confederate had already talked about it before with the subject, the researcher then engaged in a role play about the topic with the confederate as part of the training (in the good- and poor-support conditions). For example, whether the topic was a messy roommate (e.g., ‘‘Maybe you’re just too perfectionistic?’’ ‘‘I’ve never had a problem with this person’’) or fear of doing poorly on an upcoming exam (e.g., ‘‘Everyone gets a good grade on her exams, if you don’t, there is seriously something wrong,’’ ‘‘The exams are so much harder in my major’’), the confederate was trained to provide disconfirming messages geared toward that situation. Together, the researcher and confederate thought of messages that would be disconfirming but natural for that relationship.

When the subject was finished with the preinteraction survey, the confederate was brought back into the room and the researcher explained that out of both topic listing sheets, the selected subject’s topic was randomly chosen as the topic for discussion. They were told to talk about the topic for as long as they wanted and then to tell the researcher when they were finished. All of the interactions were videotaped. When the conversation was finished, the friends were placed into separate rooms again. The subjects completed a five minute survey that asked about the support their friend provided, anxiety, and satisfaction with the friendship. The subject was then left alone in the room for a 15-minute period to promote brooding. At the end of the 15 minutes, the subjects completed the final survey, which included their rumination after the interaction, anxiety, and satisfaction. The friends were then brought together, debriefed thoroughly, gave their permission for us to use their data, and were provided the opportunity to have their videotapes destroyed. Information for free counseling services was provided, however, none of the dyads appeared or reported being distressed after the debriefing.

Measures

Relationship satisfaction

Completely dissatisfiedto 7,Completely satisfied. All of the items were averaged and larger scores indicated greater satisfaction. The alpha reliabilities were .91 for T1, .93 for T2, and .92 for T3.

Closeness

The subjects’ perception of closeness with the friend was assessed at time 1 with four items (e.g., how psychologically and emotionally close they feel toward the friend, how well the friend knows him/her). The Likert-type scale ranged from 1,Not at all to 7,Very, with higher scores indicating greater closeness (α=.91).

State anxiety

Anxiety was measured with Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg, and Jacob’s (1983) state anxiety scale at time 1, 2, and 3. Six items asked the extent (on a 4-point Likert-type scale with 1 beingNot at alland 4 beingVery much) to which the subject currently felt calm, tense, upset, relaxed, content, and worried. Larger numbers indicated greater state anxiety. The reliabilities were .82 (T1), .89 (T2), and .79 (T3).

Brooding rumination

The extent to which the participants engaged in brooding rumination about the problem at time 1 and 3 was measured with items taken from the reflective ruminative response scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987). The subjects were asked three items along a 5-point Likert-type scale (1Strongly agreeto 5Strongly disagree) how much they mulled about the problem and their management of it since the conversation ended (e.g., ‘‘Mulled over the problem and thought why do I have problems other people don’t have.’’). These items were reworded to reflect brooding about the problem in general for the T1 assessment. The reliabilities were .77 (T1) and .85 (T3). These items were also revised to measure participants’ brooding about the support the friend provided in the conversation (T3) (e.g., ‘‘Thought over and over about how my friend responded to my problem and wondered ‘Why does my friend always react this way?’’’) (α=.80). Larger numbers indicate greater brooding.

Verbal rumination

A modified version of Rose’s (2002) corumination scale was used to measure the subjects’ perspective of how much they verbally ruminated during the interaction (T2). Fourteen items from the original scale that were relevant to the subject’s verbal rumination to the friend, rather than corumination, were used. The items ranged from 1, Not at all true, to 5, Very true, and focused on the following: (1) frequency of discussing the problem, (2) discussing the same problem repeatedly, (3) speculation about parts of the problem that were not understood, and (4) focusing on negative feelings. These items were averaged to create one score, with larger numbers indicating greater verbal rumination (α=.92).

Realism

more normal and typical. They found the interaction to be rather normal (M=4.28,

SD=2.04,α=.80).

Results

Manipulation checks

The means, standard deviations, and correlations for the variables are provided in Table 1. On average, the participants reported moderate levels of anxiety, relatively high levels of relationship satisfaction, and low levels of brooding rumination and verbal rumination. As a manipulation check of the support conditions, participants completed 21 items that were adapted from Xu and Burleson’s (2001) received support scale and Ellis’ (2002) perceived parental confirmation scale immediately after the conversation (T2). The items measured high and low person-centered messages and confirming and disconfirming messages, which ranged from 1,Strongly disagree, to 7,Strongly agree(e.g., ‘‘Expressed understanding of the situation that was bothering me,’’ ‘‘Discounted my feelings,’’α=.90).

These items were then adapted to allow for observer ratings of the support mes-sages. Coders were trained on the measure until satisfactory reliability was achieved (intercoder reliability=.95). Separate analyses of variance comparing positive and

negative support conditions on both the self-report measure and the coder ratings confirmed the success of the manipulation: Participants in the good-support condi-tion perceived their friends as providing better support (M=6.20,SD=.64) than the

participants in the poor-support condition (M=3.90,SD=1.14,F(1, 230)=250.01,

p<.001,η2=.37), and coders rated the confederates in the good-support condition as providing better support (M=6.75, SD=.68) than those in the poor-support

condition (M=2.56,SD=1.32,F(1, 230)=762.05,p<.001,η2=.79).

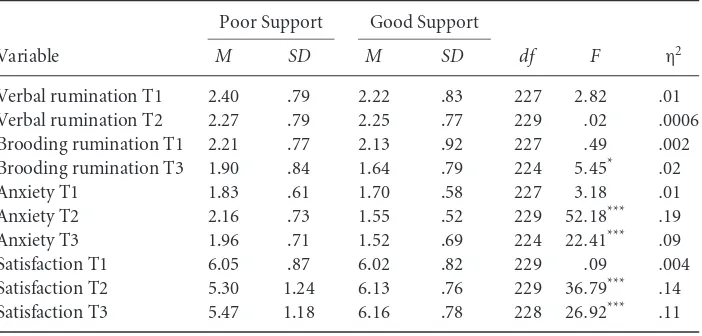

Evidence of the manipulation’s success also comes from statistically significant differences across the two conditions along several dimensions (see Table 2). Specifi-cally, the participants in the good-support condition reported being more satisfied (at T2 and T3), less anxious (at T2 and T3), and having less brooding rumination (T3) after the conversation. Participants in the good-support condition did not report verbally ruminating more during the discussion than those in the poor-support condition. There were also no significant differences in verbal rumination for males and females or for any combination of the friendship dyads.

Preliminary analyses

The subjects’ reports of interaction realism, their ratings of closeness with the friend, and the dyad’s sex composition were included as control variables in all of the regression analyses. In addition, the score for the relevant dependent variable at Time 1 (prior to the interaction) was included in the first step of all of the regressions along with the other covariates. Because of the complexity of fully accounting for all four levels of the dyadic sex compositions (i.e., sex of confederate×sex of

Rumination

a

nd

Social

Support

T.

Afifi

e

t

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for the Variables in the Models

Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

1. Verbal rumination T2

2.26 .78 —

2. Brooding rumination T1

2.17 .84 .31*** —

3. Brooding rumination T3

1.78 .83 .36*** .42*** —

4. Support condition — — –.01 –.05 –.15* —

5. Anxiety T1 1.77 .60 .12a .27*** .25*** –.12a —

6. Anxiety T2 1.88 .71 .18** .22*** .37*** –.43*** .50*** —

7. Anxiety T3 1.76 .73 .11a .17* .33*** –.30*** .42*** .63*** —

8. Satisfaction T1 6.04 .84 .04 –.06 .01 –.02 –.12a –.08 –.08 —

9. Satisfaction T2 5.69 1.12 –.01 –.12 –.08 .37*** –.22** –.49*** –.35*** .61*** — 10. Satisfaction T3 5.79 1.07 .02 –.17 –.10 .33*** –.19** –.38*** –.41*** .63*** .84*** — 11. Closeness T1 5.41 1.17 .17** –.07 .10 –.08 –.11a .01 –.03 .66*** .42*** .44*** — 12. Brooding friend’s

support T3

1.65 .77 .25*** .22** .42*** –.48*** .16* .46*** .44*** –.07 –.47*** –.52*** .09 —

13. Sex — — –.04 .002 –.02 .07 .02 –.02 –.04 –.33** –.21** –.15* –.31*** –.04 — 14. Realism 4.28 2.04 .14* –.04 –.06 .52 –.08 –.35*** –.20** .01 .31*** .19* .02 –.23** .08 —

a<.10. *p<.05. **p<.01. ***p<.001.

Human

C

ommunication

Research

39

(2013)

395

–

421

2013

International

Communication

Table 2 Means and Standard Deviations for Poor- and Good-Support Conditions

Poor Support Good Support

Variable M SD M SD df F η2

Verbal rumination T1 2.40 .79 2.22 .83 227 2.82 .01

Verbal rumination T2 2.27 .79 2.25 .77 229 .02 .0006

Brooding rumination T1 2.21 .77 2.13 .92 227 .49 .002

Brooding rumination T3 1.90 .84 1.64 .79 224 5.45* .02

Anxiety T1 1.83 .61 1.70 .58 227 3.18 .01

Anxiety T2 2.16 .73 1.55 .52 229 52.18*** .19

Anxiety T3 1.96 .71 1.52 .69 224 22.41*** .09

Satisfaction T1 6.05 .87 6.02 .82 229 .09 .004

Satisfaction T2 5.30 1.24 6.13 .76 229 36.79*** .14

Satisfaction T3 5.47 1.18 6.16 .78 228 26.92*** .11

*p<.05. ***p<.001.

dyads in comparison to other dyads, dyadic sex composition was coded as 0 for female–female and 1 for every other possible dyad combination. This control variable was not significant. As a follow-up safeguard, we removed it as a control variable and reran the results, this time with all of the possible sex combinations (as effect coding) in the analyses. Again, no significant dyadic sex composition effects emerged. Still, because of its theoretical importance, the original dummy-coded sex composition variable was retained as a control variable.

Main results

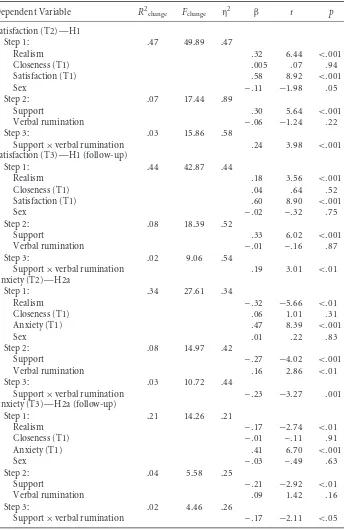

Verbal rumination predicting satisfaction

H1 predicted that support would moderate the association between verbal rumination and relationship satisfaction such that being provided with good support when verbally ruminating would increase one’s satisfaction whereas poor support would decrease it. The control variables (e.g., realism, closeness, sex, T1 satisfaction) were entered into the first step of the hierarchical regression, followed by the main effects for support (good/poor) and verbal rumination, and then the interaction for support and verbal rumination. Satisfaction at time two was the dependent variable.

The results revealed a significant verbal rumination by support interaction for satisfaction at time two (see Table 3). Follow-up analyses were conducted by running the model separately for good and poor support, with the controls in the first step and the main effect for verbal rumination in the second step of the regression. The simple slopes revealed that verbal rumination was inversely associated with relationship satisfaction when poor support was provided,β= −.34,SE=.11,t(117)= −3.18,

Table 3 Hierarchical Regression Results for H1 and H2

Dependent Variable R2

change Fchange η2 β t p

Satisfaction (T2)—H1

Step 1: .47 49.89 .47

Realism .32 6.44 <.001

Closeness (T1) .005 .07 .94

Satisfaction (T1) .58 8.92 <.001

Sex –.11 −1.98 .05

Step 2: .07 17.44 .89

Support .30 5.64 <.001

Verbal rumination –.06 −1.24 .22

Step 3: .03 15.86 .58

Support×verbal rumination .24 3.98 <.001

Satisfaction (T3)—H1 (follow-up)

Step 1: .44 42.87 .44

Realism .18 3.56 <.001

Closeness (T1) .04 .64 .52

Satisfaction (T1) .60 8.90 <.001

Sex –.02 –.32 .75

Step 2: .08 18.39 .52

Support .33 6.02 <.001

Verbal rumination –.01 –.16 .87

Step 3: .02 9.06 .54

Support×verbal rumination .19 3.01 <.01

Anxiety (T2)—H2a

Step 1: .34 27.61 .34

Realism –.32 −5.66 <.01

Closeness (T1) .06 1.01 .31

Anxiety (T1) .47 8.39 <.001

Sex .01 .22 .83

Step 2: .08 14.97 .42

Support –.27 −4.02 <.001

Verbal rumination .16 2.86 <.01

Step 3: .03 10.72 .44

Support×verbal rumination –.23 −3.27 .001

Anxiety (T3)—H2a (follow-up)

Step 1: .21 14.26 .21

Realism –.17 −2.74 <.01

Closeness (T1) –.01 –.11 .91

Anxiety (T1) .41 6.70 <.001

Sex –.03 –.49 .63

Step 2: .04 5.58 .25

Support –.21 −2.92 <.01

Verbal rumination .09 1.42 .16

Step 3: .02 4.46 .26

To assess whether the aforementioned effects would persist, the same model was then run for satisfaction at time three (see Table 3). The simple slopes revealed that verbal rumination was positively associated with satisfaction at time three when good support was received, β=.19, SE=.06, t(99)=3.10, p<.01, but not when poor support was received,β= −.18,SE=.11,t(117)= −1.62,ns. Thus, the impact

of verbal rumination on satisfaction had a more long-lasting response when good support was received.

Verbal rumination predicting state anxiety and brooding rumination

H2 predicted that social support would moderate the association between verbal rumination and (H2a) anxiety and (H2b) brooding rumination such that being provided with good support when verbally ruminating would decrease one’s anxiety and brooding whereas poor support would increase one’s anxiety and brooding. In the model for anxiety, the control variables (e.g., realism, closeness, sex, T1 anxiety) were entered into the first step of the regression, followed by the main effects for support and verbal rumination, and then the interaction for support and verbal rumination. Anxiety at time two was the dependent variable.

The results revealed a significant interaction between verbal rumination and support for anxiety at time two (see Table 3). Follow-up analyses were conducted by running the model separately for good and poor support, with the controls in the first step and the main effect for verbal rumination in the second step. The simple slopes suggested that under poor support, verbal rumination was positively associated with anxiety,β=.27,SE=.07,t(117)=3.61,p<.001. That is, the more subjects verbally ruminated about the stressor, the more anxious they were immediately after the conversation when they were provided with poor support, providing partial support for H2a. Verbal rumination was not significantly associated with anxiety in the good-support condition,β= −.01,SE=.06,t(99)= −.13,ns. In other words, when

the participants were provided with good support, their verbal rumination did not affect their anxiety.

To determine the longevity of these effects, the same model was then run for anxiety at time three. Similar to anxiety at time two, there was a significant interaction between verbal rumination and support for anxiety at time three (see Table 3). The simple slopes indicated that when participants received poor support, greater verbal rumination was significantly associated with greater anxiety 20 minutes later,β=.19, SE=.07, t(116)=2.54, p<.05, but receiving good support did not significantly affect participants’ anxiety,β= −.03,SE=.09,t(97)= −.27,ns. Therefore, the effect

of verbal rumination on anxiety may persist when poor support is received.

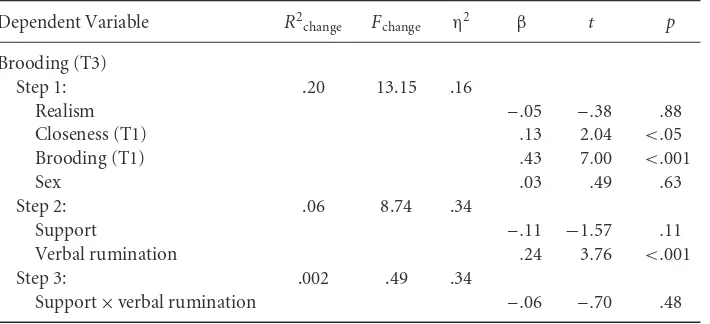

Table 4 Hierarchical Regression Results for H2b

Dependent Variable R2change Fchange η2 β t p

Brooding (T3)

Step 1: .20 13.15 .16

Realism –.05 –.38 .88

Closeness (T1) .13 2.04 <.05

Brooding (T1) .43 7.00 <.001

Sex .03 .49 .63

Step 2: .06 8.74 .34

Support –.11 −1.57 .11

Verbal rumination .24 3.76 <.001

Step 3: .002 .49 .34

Support×verbal rumination –.06 –.70 .48

providing a lack of support for H2b. There was only a significant main effect for verbal rumination, with verbal rumination being positively associated with brooding (see Table 4). Therefore, the more the subject verbally ruminated about their stressor during the interaction, the more they brooded afterward, regardless of the type of support received.

Verbal rumination, brooding rumination, anxiety, and satisfaction

H3 predicted that the degree to which people’s verbal rumination affects their (H3a) anxiety and (H3b) relationship satisfaction depends upon the type of support they receive and the extent of their brooding rumination afterward. The model for anxiety was analyzed first. The control variables (e.g., realism, closeness, sex, anxiety T1) were entered into the first step of the hierarchical regression, followed by the main effects for support, verbal rumination, and brooding rumination in the second step, the two-way interactions in the third step, and the three way interaction in the fourth step. Anxiety (T3) was the dependent variable.

There was no significant three-way interaction for verbal rumination, brooding rumination and support for anxiety, providing a lack of support for H3a. The analyses also revealed a nonsignificant interaction between brooding and support on anxiety, but a positive, main effect for brooding on anxiety (see Table 5). The results suggest that greater brooding tends to increase anxiety, regardless of whether one verbally ruminates or the support received.

Table 5 Hierarchical Regression Results for H3

Dependent Variable R2change Fchange η2 β t p

Anxiety (T3)—H3a

Step 1: .21 14.26 .21

Realism –.17−2.74 <.01

Closeness (T1) –.01 –.11 .91

Anxiety (T1) .41 6.70 <.001

Sex –.03 –.49 .63

Step 2: .07 7.17 .28

Support –.19−2.68 <.01

Verbal rumination .02 .32 .75

Brooding .20 3.14 <.01

Step 3: .02 1.91 .30

Support×verbal rumination –.15−1.83 .06

Support×brooding –.02 –.27 .79

Brooding×verbal rumination –.08−1.28 .20

Step 4: .004 1.12 .31

Support×brooding×verbal rumination –.09−1.26 .29

Satisfaction (T3)—H3b

Step 1: .44 41.82 .44

Realism .18 3.50 .001

Closeness (T1) .04 .52 .64

Satisfaction (T1) .60 8.85 <.001

Sex –.01 –.18 .86

Step 2: .08 12.11 .51

Support .32 5.73 <.001

Verbal rumination .02 .31 .76

Brooding –.06−1.18 .24

Step 3: .03 4.63 .55

Support×verbal rumination .14 2.02 <.05

Support×Brooding .14 2.08 <.05

Brooding×verbal rumination –.04 –.84 .40

Step 4: .001 .55 .55

Support×brooding×verbal rumination .05 .74 .46

that under conditions of poor support, greater brooding significantly decreased satisfaction, β= −.23, SE=.10, t(117)= −2.29, p<.05. However, brooding was not significantly associated with satisfaction when receiving good support,β=.11,

SE=.06,t(97)=1.79,ns.

A supplemental analysis was also conducted to examine whether the changes in relationship satisfaction were really a result of brooding about the friend’s lack of social support rather than brooding about one’s problem and ability to manage it. The control variables (e.g., realism, closeness, sex, T1 satisfaction) were entered into the first step of the hierarchical regression, followed by the main effects for support, verbal rumination, and brooding about the friend’s support in the second step, the two way interactions in the third step, and the three way interaction in the fourth step. Satisfaction (T3) was the dependent variable. There was not a significant three-way interaction among verbal rumination, social support, and brooding for relationship satisfaction. There was only a significant two-way interaction between brooding about the friend’s support and the support condition for relationship satisfaction,β=.33, SE=.18,t(214)=2.90, p<.01, η2=.69. Follow-up analyses of the simple slopes indicated that when poor support is received, greater brooding about the support significantly decreased relationship satisfaction,β= −.69,SE=.08,t(117)= −8.86,

p<.001. Brooding about the friend’s support when good support was received was not significantly associated with satisfaction,β= −.03,SE=.13,t(97)= −.22,ns. In

other words, when participants receive poor support by a friend and they brood about the friend’s support afterward, they become more dissatisfied with the friendship, regardless of whether they were verbally ruminating.

Discussion

Social support typically buffers the negative effects of stress on people’s health (see Afifi et al., 2011). When people talk about a problem repeatedly, however, it can challenge even the best support providers’ communication skills. Well-intentioned friends who normally provide good support may begin to wane in their support efforts, which could further perpetuate the ruminator’s anxiety and potentially hurt the relationship.

These findings suggest that good support may help someone who is verbally ruminating feel good about the friendship, but it may not alleviate his/her anxiety. People might still brood after they verbally ruminate, no matter what their friends tell them. On the other hand, poor support could make the friend’s anxiety, and the relationship itself, worse. Finally, the results suggest that verbal rumination and brooding rumination may operate as independent processes that negatively affect anxiety. All of these findings held true regardless of biological sex.

The moderating role of social support

The findings presented here suggest that receiving poor support when verbally ruminating may have more damaging, lasting effects than good support has positive effects—particularly for the ruminator’s anxiety. The effects of verbal rumination on anxiety were more long-lasting when combined with poor support compared to when verbal rumination was analyzed alone. Poor support may play a more powerful role than good support in determining people’s anxiety after they have verbally ruminated.

Although good support may make people feel better about their friendship, perhaps only individuals can make themselves feel better psychologically when they are cognitively ruminating. Verbal rumination was positively associated with brooding, regardless of the type of support received. Even though this study showed that social support did not decrease people’s anxiety and brooding when they were verbally ruminating, there are other communication-based and noncommunication-based factors that could help people reduce their brooding.

Research shows that self-disclosing can often reduce anxiety and rumination (e.g., Stiles et al., 1992). Interventions that help people regulate their emotions (see Kemeny et al., 2012) and/or distract themselves from their stressor have also been shown to reduce rumination and anxiety (e.g., Huffziger, Reinhard, & Kuehner, 2009; Selby, Anestis, Bender, & Joiner, 2009). Research on stress and coping has also shown that reappraising a stressor can reduce rumination (see Denson, Spanovic, & Miller, 2009). A more precise focus on reappraisal could be a fruitful avenue of future research.

The extent to which a person can stop brooding and become less anxious may depend upon other individual-level factors. Numerous scholars (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema & Larson, 1999; Zoccola et al., 2010) have argued that brooding can be induced by a stressor, but it is also a stable personality trait. People who are high ruminators may approach stress differently and respond to others’ social support differently than low ruminators (see Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). People who have a ruminative coping style tend to seek support more from others but tend to not fully recognize the support provided (Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). Indeed, some people who are high ruminators may have a difficult time feeling better, even if they are provided with good support simply because of their personality.

(Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). Their cognitive and emotional resources may be drained from verbally and cognitively ruminating so often, making it difficult to think of creative solutions—by themselves or with others. Therefore, when non-ruminators actually ruminate about a stressor, they may find it easier to reframe cognitively the stressor compared to someone who ruminates on a more consistent basis. Ego-depletion may also make it more likely that ruminators violate social norms and talk too much about their stress to others because they cannot effectively solve problem alone (Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). If others then begin to deny that person support because of the lack of problem-solving, such denial may further perpetuate the ruminator’s anxiety, while simultaneously creating an emotional wedge in the relationship.

Other personality traits, like a need for closure (Kruglanski & Webster, 1996), could also interact with verbal and brooding rumination to affect people’s anxiety. A need for closure is an individual’s desire to have a definitive answer or solution to a problem rather than uncertainty (Webster & Kruglanski, 1997). For example, individuals with a high need for closure may be more likely to brood, to be bothered by their brooding, and turn to others for support in order to gather information and reduce their uncertainty regarding their problem. On the other hand, people who have a low need for closure may brood less and, subsequently, have less of a need for social support, because they are more comfortable with uncertainty.

The findings from this study also enhance the existing research on corumination. The research on corumination thus far has focused almost exclusively on gender, with the argument being that female–female friendships tend to co-ruminate the most and experience the benefits of greater relationship satisfaction and the consequences of greater internalizing problems as a result (e.g., Rose, 2002; Smith & Rose, 2011). Yet, rather than focusing almost entirely on biological sex, a stronger theoretical argument may be to examine other communication processes occurring in the talk that might complicate this finding. We found that verbal rumination does not necessarily result in enhanced satisfaction or increased anxiety, but that it depends upon the type of support received. The results from this study held true regardless of participant sex. We would also note that neither participant’s sex nor sex compositions within the friendship dyad differed in their level of verbal rumination.

The independent effects of verbal rumination and brooding rumination on anxiety

Unlike what was predicted, verbal rumination and brooding rumination appear to function as separate processes that adversely affect anxiety. We hypothesized that individuals who are provided with poor support when verbally ruminating would brood about it afterward and experience greater anxiety and lower relationship satisfaction as a result. Similar to previous research, verbal rumination and brooding rumination were moderately and positively correlated (r=.36). However, they

note, social sharing and brooding rumination may ‘‘not be manifestations of one and the same process of ‘working through’ the emotional experience’’ of a stressor (p. 250). One possibility is that verbal rumination activates the public aspect of people’s ability to regulate their emotions whereas brooding affects their ability to privately regulate their emotions (Rime et al., 1992). The failure to adequately regulate one’s emotions in both situations could increase anxiety. These processes do not necessarily depend on each other—they can both directly affect anxiety.

There may also be important individual differences in people’s natural tendencies to experience and communicate their emotions, which may translate in subtle differences in verbal rumination and brooding rumination. As Rime et al. (1992) contend, some people verbally ruminate at a high rate as a way to manage a stressor, whereas others internalize their emotions by brooding and rarely ever express their stress verbally. Still others ruminate about their stress through brooding and verbal rumination.

These individual differences could have important implications physiologically. Byrd-Craven et al. (2008) found that co-ruminating among female friends was associated with increased cortisol. Even though we found that social support did not interact with verbal rumination and brooding to affect anxiety, it could be that individuals process verbal rumination and brooding rumination differently and have varying physiological (e.g., bodily indicators of anxiety and stress) responses as a result.

Another possibility is that when people brood, it prompts them to verbally ruminate, which makes them even more anxious when they receive poor support. This type of moderated mediation model, however, was impossible to test with the design of the current sample. We could not prove that brooding prompted people to verbally ruminate, even though other research suggests this is the case (Tait & Silver, 1989). Additional research is required that can tease out these associations over time. Although there are numerous theoretical and practical implications of this study, they must be set within its limitations. Even though the participants talked about the topic that they tended to verbally ruminate about the most with their friend, the mean levels of rumination were rather low. What this suggests, however, is that the findings are conservative estimates. Greater amounts of verbal rumination, as might be expected with samples of recently bereaved adults (see Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999) or people who have recently experienced another type of trauma, would probably provide even larger effect sizes. Of course, ethical concerns prohibit the conduct of experimental designs with sensitive populations and/or topics. Correlational, over-time, studies in more naturalistic settings, however, may provide important insights. The ethnic diversity of the sample in this investigation (albeit restricted in age) gives promise of the applicability of these findings across a wide range of populations.

stressor. We only examined the effect of the support condition and not individuals’ perceptions about the effectiveness of the support.

This study provides new information about the link between verbal rumination and brooding rumination and the moderating role of social support. Numerous researchers assume that disclosure of stressors will alleviate anxiety. However, the findings from this study demonstrate that when people repeatedly talk to others about their stressors (which seems more commonplace than writing down stressors), the type of support provided is fundamental in many ways, but not all, to how the ruminator feels afterward. In some instances, talking about a stressor to someone who is unsupportive could do more damage than not talking about it at all.

References

Afifi, T. D., & McManus, T. (2010). Divorce disclosures and adolescents’ physical and mental health and parental relationship quality.Journal of Divorce & Remarriage,51, 83–107. doi: 10.1080/10502550903455141.

Afifi, T. D., & Steuber, K. (2009). The Risk Revelation Model (RRM) and strategies used to reveal secrets.Communication Monographs,76, 144–176. doi: 10.1080/0363775090 2828412

Afifi, W. A., Afifi, T. D., & Merrill, A. (2013).Uncertainty and communal coping in the context of a natural disaster. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Afifi, T. D., Caughlin, J., & Afifi, W. A. (2007). Exploring the dark side (and light side) of avoidance and secrets. In B. Spitzberg & B. Cupach (Eds.),The darkside of interpersonal relationships(2nd ed., pp. 61–92). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Afifi, T. D., Granger, D., Denes, A., Joseph, A., & Aldeis, D. (2011). Parents’ communication skills and adolescents’ salivaryα-amylase and cortisol response patterns.Communication Monographs,78, 273–295. doi: 10.1080/03637751.2011.589460

Afifi, T. D., Olson, L. N., & Armstrong, C. (2005). The chilling effect and family secrets.

Human Communication Research,31, 564–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2005.tb00883.x Albrecht, T. L., & Goldsmith, D. J. (2003). Social support, social networks, and health. In

A. Matshall, K. L. Miller, R. Parrot & T. L. Thompson (Eds.),Handbook of health communication(pp. 263–284). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Altman, I., & Taylor, D. (1973).Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. New York: Holt.

Bippus, A. (2000). Humor usage in comforting episodes: Factors predicting outcomes.

Western Journal of Communication,64, 359–384. doi: 10.1080/105703100093 74682

Bippus, A. (2001). Recipients’ criteria for evaluating the skillfulness of comforting communication and the outcomes of comforting interactions.Communication Monographs,68, 301–313. doi: 10.1080/03637750128064

Burleson, B. R. (1982). The development of comforting communication skills in childhood and adolescence.Child Development,53, 1578–1588. doi: 10.2307/1130086

Burleson, B. R. (2009). Understanding the outcomes of supportive communication: A dual process approach.Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,26, 21–38. doi:

10.1177/0265407509105519

Burleson, B. R., & Goldsmith, D. J. (1998). How the comforting process works: Alleviating emotional distress through conversationally induced reappraisals. In P. A. Andersen & L. K. Guerrero (Eds.),The handbook of emotion and communication(pp. 245–280). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Burleson, B. R., & MacGeorge, E. L. (2002). Supportive communication. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Daly (Eds.),Handbook of interpersonal communication(3rd ed., pp. 374–424). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Byrd-Craven, J., Geary, D. C., Rose, A. J., & Ponzi, D. (2008). Co-ruminating increases stress hormone levels in women.Hormones and Behavior,53, 489–492. doi:

10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.12.002

Calmes, C. A., & Roberts, J. E. (2008). Rumination in interpersonal relationships: Does co-rumination explain gender differences in emotional distress and relationship satisfaction among college students?Cognitive Therapy and Research,32, 577–590. doi: 10.1007/s10608-008-9200-3

Checton, M. G., & Greene, K. (2012). Beyond initial disclosure: The role of prognosis and symptom uncertainty in patterns of disclosure in relationships.Health Communication, 27, 145–157. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.571755

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis.

Psychological Bulletin,98, 310–357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Conway, C. C., Rancourt, D., Adelman, C. B., Burk, W., & Prinstein, M. J. (2011). Depression socialization within friendship groups at the transition to adolescence: The roles of gender and group centrality as moderators of peer influence.Journal of Abnormal Psychology,120, 857–867. doi: 10.1037/a0024779

Denes, A., Afifi, T.D., Granger, D., Joseph, A., & Aldeis, D. (in press). Interparental conflict and parents’ inappropriate disclosures: Relations to parents’ and children’s salivary

α-amylase and cortisol. In J. Honeycutt, C. Sawyer, & S. Keaton (Eds.),The influence of communication in physiology and health status. Peter Lang.

Denson, T. F., Spanovic, M., & Miller, N. (2009). Cognitive appraisals and emotions predict cortisol and immune responses: A meta-analysis of acute laboratory social stressors and emotion inductions.Psychological Bulletin,135, 823–853. doi: 10.1037/a0016909 Derlega, V. J., Winstead, B. A., & Folk-Barron, L. (2000). Reasons for and against disclosing

HIV-Seropositive test results to an intimate partner: A functional perspective. In S. Peteronio (Ed.),Balancing the secrets of private disclosures(pp. 53–71). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Derlega, V. J., Winstead, B. A., Gamble, K. A., Kelkar, K., & Khuanghlawn, P. (2010). Inmates with HIV, stigma, and disclosure decision making.Journal of Health Psychology,15, 258–273. doi: 10.1177/1359105309348806

Derlega, V. J., Winstead, B. A., Greene, K., Serovich, J., & Elwood, W. N. (2004). Reasons for HIV disclosure/nondisclosure in close relationships: Testing a model of HIV disclosure decision making.Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,23, 747–767.

Ellis, K. (2002). Perceived parental confirmation: Development and validation of an instrument.Southern Communication Journal,67, 319–334. doi:

Greene, K. (2009). An integrated model of health disclosure decision making. In T. D. Afifi & W. A. Afifi (Eds.),Uncertainty, information management, and disclosure decisions: Theories and applications(pp. 226–253). New York: Routledge.

Guerrero, L. K., Jones, S. M., & Burgoon, J. K. (2000). Responses to nonverbal intimacy change in romantic dyads: Effects of behavioral valence and degree of behavioral change on nonverbal and verbal reactions.Communication Monographs,67, 325–346. doi: 10.1080/03637750009376515

Hankin, B. L., Stone, L., & Wright, P. A. (2010). Corumination, interpersonal stress generation, and internalizing symptoms: Accumulating effects and transactional influences in a multiwave study of adolescents.Development and Psychopathology,22, 217–235. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990368

Holmstrom, A. J., & Burleson, B. R. (2011). An initial test of a cognitive-emotional theory of esteem support messages.Communication Research,38, 326–355. doi: 10.1177/

0093650210376191

Holmstrom, A. J., Burleson, B. R., & Jones, S. (2005). Some consequences for helpers who deliver ‘‘Cold Comfort’’: Why it’s worse for women than men to be inept when providing emotional support.Sex Roles,53, 153–172. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-5676-4

Huffziger, S., Reinhard, I., & Kuehner, C. (2009). A longitudinal study of rumination and distraction in formerly depressed inpatients and community controls.Journal of Abnormal Psychology,118, 746–756. doi: 10.1037/a0016946

Huston, T. L., McHale, S. M., & Crouter, A. C. (1986). When the honeymoon’s over: Changes in the marriage relationship over the first year. In R. Gilmour & S. Duck (Eds.),

The emerging field of personal relationships(pp. 109–132). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Jones, S. M. (2004). Putting the person into person-centered and immediate emotional

support: Emotional change and perceived helper competence as outcomes of comforting in helping situations.Communication Research,31, 338–360. doi: 10.1177/

0093650204263436

Jones, S. M., & Guerrero, L. K. (2001). The effects of nonverbal immediacy and verbal person centeredness in the emotional support process.Human Communication Research,27, 567–596. doi: 10.1093/hcr/27.4.567

Jones, S. M., & Wirtz, J. G. (2006). How does the comforting process work? An empirical test of an appraisal-based model of comforting.Human Communication Research,32, 217–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2006.00274.x

Kaniasty, K., & Norris, F. H. (1993). A test of the social support deterioration model in the context of natural disasters.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,64, 395–408. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.64.3.395

Kelly, A., & Macready, D. (2009). Why disclosing to a confidant can be so good (or so bad) for us. In T. D. Afifi & W. A. Afifi (Eds.),Uncertainty, information management, and disclosure decisions: Theories and applications(pp. 384–402). New York: Routledge. Kemeny, M. E. et al. (2012). Contemplative/emotion training reduces negative emotional

behavior and promotes prosocial responses.Emotion,12, 338–350. doi: 10.1037/ a0026118

Kruglanski, A. W., & Webster, D. M. (1996). Motivated closing of the mind: ‘‘Seizing’’ and ‘‘freezing.’’Psychological Review,103, 263–283. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.103.2.263 Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984).Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. McLaren, R. M., & Solomon, D. H. (2008). Appraisals and distancing responses to hurtful

McLaren, R. M., Solomon, D. H., & Priem, J. (2011). Explaining variation in

contemporaneous responses to hurt in premarital romantic relationships: A relational turbulence model perspective.Communication Research,38, 543–564. doi: 10.1177/ 0093650210377896

Miller, K. I. (2007). Compassionate communication in the workplace: Exploring processes of noticing, connecting, and responding.Journal of Applied Communication Research,35, 223–245. doi: 10.1080/00909880701434208

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1987). Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory.

Psychological Bulletin,101, 259–282. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.259

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms.Journal of Abnormal Psychology,109, 504–511. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Davis, C. G. (1999). ‘‘Thanks for sharing that’’: Ruminators and their social support networks.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,77, 801–814. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.4.801

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Larson, J. (1999).Coping with loss. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and

posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,61, 115–121. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115

Pearce, W. B., & Cronen, V. (1980).Communication, action, and meaning: The creation of social realities. New York: Praeger.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1989).Opening up: The healing power of confiding in others. New York: W. Morrow.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1995).Emotion, disclosure, and health. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Petronio, S. (1991). Communication boundary management: A theoretical model of managing disclosure of private information between marital couples.Communication Theory,1, 311–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.1991.tb00023.x

Petronio, S. (2000). The boundaries of privacy: Praxis of everyday life. In S. Petronio (Ed.),

Balancing the secrets of privacy disclosures(pp. 37–49). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Petronio, S. (2002).Boundaries of privacy: Dialectics of disclosure. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. Petronio, S., Reeder, H. M., Hecht, M. L., & Ros-Mendoza, T. M. (1996). Disclosure of sexual

abuse by children and adolescents.Journal of Applied Communication Research,24, 181–199.

Priem, J., & Solomon, D. H. (2011). Relational uncertainty and cortisol responses to hurtful and supportive messages from a dating partner.Personal Relationships,18, 198–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01353.x

Priem, J., McLaren, R., & Solomon, D. H. (2010). Relational messages, perceptions of hurt, and biological stress reactions to disconfirming interaction.Communication Research,37, 48–72. doi: 10.1177/009365020351470

Rime, B., Philippot, P., Boca, S., & Mesquita, B. (1992). Long-lasting cognitive and social consequences of emotion: Social sharing and rumination.European Review of Social Psychology,3, 225–258. doi: 10.1080/14792779243000078

Saxbe, D., & Repetti, R. L. (2010). For better or worse? Coregulation of couples’ cortisol levels and mood states.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,98, 92–103. doi: 10.1037/ 20016959

Schwartz-Mette, R. A., & Rose, A. J. (2012). Co-rumination mediates contagion of internalizing symptoms within youths’ friendships.Developmental Psychology,48, 1355–1365. doi: 10.1037/a0027484

Selby, E. A., Anestis, M. D., Bender, T. W., & Joiner, T. E. (2009). An exploration of the emotional cascade model in borderline personality disorder.Journal of Abnormal Psychology,118, 375–387. doi: 10.1037/a0015711

Smith, R. L., & Rose, A. J. (2011). The ‘‘cost of caring’’ in youths’ friendships: Considering associations among social perspective taking, co-rumination, and empathic distress.

Developmental Psychology,47, 1792–1803. doi: 10.1037/a0025309

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R., & Jacobs, G. A. (1983).Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists.

Starr, L. R., & Davila, J. (2009). Clarifying co-rumination: Associations with internalizing symptoms and romantic involvement among adolescent girls.Journal of Adolescence,32, 19–37. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.12.005

Stiles, W. B. (1987). Verbal response modes as intersubjective categories. In R. L. Russell (Ed.),Language in psychotherapy: Strategies of discovery(pp. 131–170). New York: Plenum.

Stiles, W. B., Shuster, P. L., & Harrigan, J. A. (1992). Disclosure and anxiety: A test of the fever model.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,63, 980–988. doi: 10.1037/ 0022-3514.63.6.980

Stone, L. B., Hankin, B. L., Gibb, B. E., & Abela, J. R. Z. (2011). Co-rumination predicts the onset of depressive disorders during adolescence.Journal of Abnormal Psychology,120, 752–757. doi: 10.1037/a0023384

Stone, L. B., Uhrlass, D. J., & Gibb, B. E. (2010). Co-rumination and lifetime history of depressive disorders in children.Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology,39, 597–602. doi: 10.1080/15274416.2010.486323

Stroebe, W., Zech, E., Stoebe, M. S., & Abakoumkin, G. (2005). Does social support help in bereavement?Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,24, 1030–1050. doi:

10.1521/jscp.2005.24.7.1030

Tait, R., & Silver, R. C. (1989). Coming to terms with major negative life events. In J. S. Uleman & J. A. Bargh (Eds.),Unintended thought(pp. 351–382). New York: Guilford. Webster, D. M., & Kruglasnki, A. W., (1997). Cognitive and social consequences of the need

for cognitive closure.European Review of Social Psychology,8, 133–173. doi: 10.1080/ 14792779643000100

Wheeless, L. R. (1976). Self-disclosure and interpersonal solidarity: Measurement, validation, and relationships.Human Communication Research,3, 47–61. doi:

10.1111/j.1468-2958.1976.tb00503.x

Wheeless, L. R., & Grotz, J. (1977). The measurement of trust and its relationship to self-disclosure.Human Communication Research,3, 250–257. doi:

10.1111/j.1468-2958.1977.tb00523.x

Xu, Y., & Burleson, B. R. (2001). Effects of sex, culture, and support type on perceptions of spousal social support: An assessment of the ‘‘support gap’’ hypothesis in early marriage.

Zawadzki, M. J., Graham, J. E., & Gerin, W. (2012). Rumination and anxiety mediate the effect of loneliness on depressed mood and sleep quality in college students.Health Psychology,10, 1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0029007