Marcelo Paladino

INSTITUTO DEALTOSESTUDIOSEMPRESARIALES, IAE-UNIVERSIDADAUSTRAL

Founded as a small mechanical workshop by an Italian immigrant in general purpose machine, the T-4, that is ideal for the Latin American market. Turri’s choice of reputable but second-class

the 1920s, Turri had come to be a major player in the technologically

sophisticated “CNC” (computerized numerically controlled) sector of the Japanese firm is interesting in that there is less likelihood of its being absorbed by the new partner. Turri also is able to

machine tool market by the late 1980s. The case describes this transition,

leading to the company’s decision to abandon the manufacture of tradi- adapt and improve the T-4 technology as a base for new product lines.

tional lathes and to produce only CNCs. However, the global machine

tool industry has changed significantly over the past decade, and Turri Just as the company was about to capitalize on this technol-ogy in a more favorable economic environment, and with

faces difficult new challenges. The sale of a family business to corporate

interests may provide the access to resources, technology, and markets the opening of the Brazilian market, it experienced operating problems that can be traced to a major restructuring in which

that are needed for success, or it may smother the inventiveness and

entrepreneurial spirit of the founder. As Turri was sold twice, first to a many experienced managers resigned. Though most were re-placed, the production management team was left crippled.

Swiss multinational and later to a large Argentine conglomerate, the case

provides a rich opportunity to explore this question. The Swiss were Scheduling bottlenecks and unmet deliveries lead to cancelled orders, and sales dropped until a crisis point was reached in

instrumental in developing a state-of-the-art technology policy and in

initiating an export strategy for Turri, but it was the founder’s reputation 1990. In this context, the company once again searched for a foreign partner but this time one with financial resources

for quality and innovation in the domestic market that had created the

and complementary product lines. One possibility is Mandelli,

foundations for success.J BUSN RES2000. 50.15–28. 2000 Elsevier

the Italian machine center manufacturer, with whom Turri’s

Science Inc. All rights reserved.

CEO then began negotiating.

This is truly a global case, in which one may see the interplay of Turri with Japanese, Swiss, and Italian companies operating within the policy context of Mercosur in Brazilian

T

he case traces the various stages of economic policyand Argentine markets. in Latin America, from import substitution and

protec-tionism through trade liberalization and the new op-portunities presented by Mercosur, the regional trading bloc.

TURRI, S.A.

It also describes the turbulent economic and politicalenviron-ment of Argentina in which the company operated. It was In September 1990, the chief executive officer of Turri, S.A. this environment and specifically the severe recession of the was concerned about the machine tool company’s scarcity of early 1980s that led the Swiss investors to sell to ITSA, the funds. New loans from commercial banks would be difficult Argentine conglomerate, which was accustomed to managing to obtain given the company’s current financial situation and under conditions of hyperinflation and could take advantage the uncertain economic conditions in Argentina. The only of sharp devaluations by selling in export markets at competi- remaining source of financing was ITSA, the holding company tive prices. that owned Turri, unless a foreign partner was approached. The issue of technology acquisition by a Latin American The CEO, Mr. Gilligan, had recently begun conversations company may be examined through new management’s quest, with Mr. Giancarlo Mandelli, president of a leading Italian under ITSA, for strategic alliances abroad. Such an alliance is manufacturer of machining centers, and he was now preparing finally struck through agreements with a Japanese producer to negotiate a joint venture with Mandelli.

of CNC machine tools, which licenses the production of a Turri, S.A. was a producer of technologically advanced, numerically controlled (CNC) lathes for the machining of industrial parts. To rationalize expenses and build a high-tech

Address Correspondence to Marcelo Paladino, Mariano Acosta S/No,

Derqui-(1629) Pilar-Buenos Aires, Argentina. image for the company, the board of directors had approved

Journal of Business Research 50, 15–28 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

16

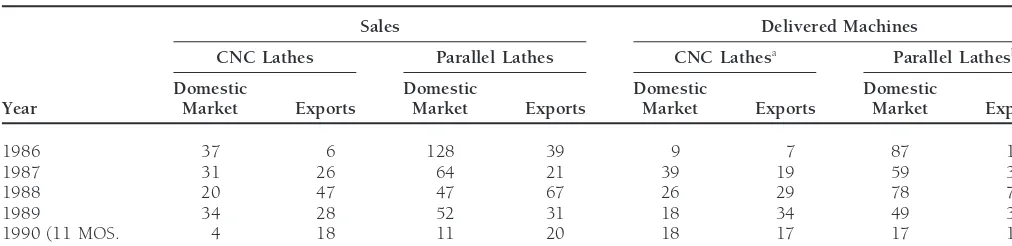

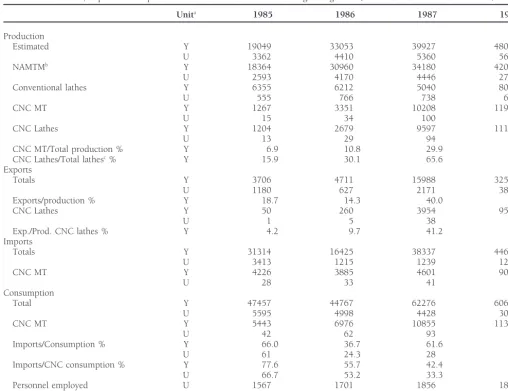

J Busn Res M. Paladino 2000:50:15–28Table 1. Sales Volume and Deliveries

Sales Delivered Machines

CNC Lathes Parallel Lathes CNC Lathesa Parallel Lathesb

Domestic Domestic Domestic Domestic

Year Market Exports Market Exports Market Exports Market Exports

1986 37 6 128 39 9 7 87 19 bAverage value: US$12,000 per machine.

a plan to phase out its line of traditional, parallel lathes be-

Company Background

cause, as the CEO explained, “these were not compatible withAs often occurred in Argentina in the 1920s, an Italian immi-new technologies, and sales have continued to decline.” (Data

grant opened a shop, placed his name on the door, and soon on sales volume and deliveries of the two product lines during

had a successful business. In this case, the Italian was a me-the period 1986 to 1990 are shown in Table 1.)

chanic named Turri, and the workshop he established was Even with the reduced sales volume, Turri had sometimes

to produce single-pulley lathes. In time, this family-owned failed to meet production plans. The situation was further

business increasingly gained prestige in the domestic MT mar-complicated by drastic changes in the Argentine political and

ket and slowly became the leader in parallel lathe manufacture. economic environment. The current president, Carlos Menem,

In 1957, the company was acquired by an international had been in office only one year and had already faced two

Swiss group that carried out a thorough transformation of hyperinflation periods, in July and December of 1989.

Turri’s technology and human resources. After this transfor-mation, Turri began exporting its main product, parallel

Lathe Products

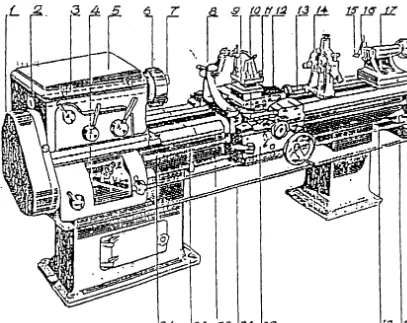

lathes, to other Latin American countries and soon became the indisputable leader in this MT segment. In the domestic A lathe is a machine tool that shapes the parts to be machinedmarket, company products were protected by a 33% tariff. by scraping off shavings of material. The part rotates around

In the 1960s and 1970s, Turri’s technology policy was its axis, and a cutting tool shaves off the material to be

re-state-of-the-art, and it made major investments in product moved. The most common type is known as theParallel Lathe

development and plant tooling. Turri was the first Argentine (shown in Figure 1).

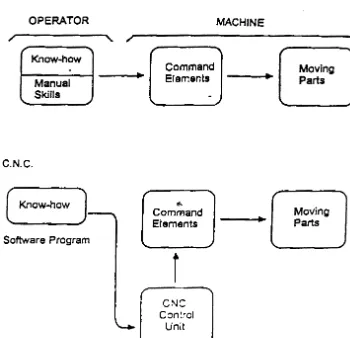

company to venture into numerical control technology, which The computerized numerical control (CNC) is a system

was a turning point for the metalworking industry in general applied to machine tools (MTs) to automate and control all

and for the MT segment in particular. Mastering this technol-their actions, including: carriage, headstock, tool post, and

ogy involved the use of computers in machining processes, tailstock center movements; tool feeding and spindle speeds

as MT command and control elements. Using in-house devel-and directions; cutting tool devel-and part changeovers; devel-and normal

opment engineering capabilities, in late 1979, Turri manufac-operations.

tured some prototype models that were actually nothing more The information needed to perform machining operations

than conventional machines retrofitted with a CNC unit. This on a particular part required preparing a program. The

combi-limited their performance: for example, cutting speed was not nation of a lathe and a CNC resulted in a product known

constant due to conventional gearboxes and motors. as a CNC lathe. Figure 2 shows simplified charts of both

In 1982, after a severe recession that afflicted domestic conventional and CNC operating systems. Figure 3 features

industries, the Swiss group decided to sell off the company, a photograph of Turri’s model T-4.

which was acquired by ITSA, an Argentine capital holding As a result of progress made in mastering the control unit

company engaged in the oil and construction businesses. electronic technology and in simplifying its programming,

ITSA’s top management was known for its unflagging opti-MTs equipped with these units had become widespread. Also

mism and for its interest in taking on ambitious new ventures. noticeable was a technological trend towards integrating MTs

Since 1979, a decline in public works contracts prompted the with other automation elements, such as robots and

computer-group to look for business opportunities in other industry aided design and manufacture control systems (CAD/CAM),

segments to diversify their portfolio but always in activities which created Flexible Production Cell systems and Flexible

that contributed to national economic development. Manufacture Systems (FMS). This trend placed great demands

ITSA acquired Turri with the goal of turning it into the for design and production on MT manufacturers, and created

Figure 1. Main components of a center lathe: 1, gearbox cover; 2, main shaft bore for bar insertion; 3, main shaft; 4, feed gearbox; 5, headstock; 6, chuck (faceplate); 7, chuck gripping jaws; 8, tool slide; 9, tool post; 10, cross slide; 11, turntable; 12, charriot; 13, lathe bed guide bars; 14, fixed middle rest; 15, tailstock center; 16, tailstock shaft; 17, tailstock; 18, feed shaft; 19, switch reverse shaft; 20, carriage with apron; 21, turnings and coolant tray; 22, rack; 23, lathe bed; 24, leadscrew.

challenge of developing this important industrial sector, which ments for the purchase of new technology from Takisawa, a second-rate though renowned firm in the MT market. As part they considered vital to domestic industrial growth. In

re-sponse to the perceived trend toward economic liberalization, of these agreements, Takisawa discontinued manufacturing of its model T-4 CNC lathe (some of whose vital pieces were the new Turri management installed by ITSA began to redefine

the market and to rethink the product technology strategy in wearing out through friction with metal shavings) and licensed the technology to Turri. This breakthrough resulted in Turri’s accordance with new market requirements. Until this time,

Turri’s growth had benefitted from the protection of a rela- successful marketing, in 1984, the first licenced numerically controlled machine in the country, the T-4 CNC. Exporting to tively closed economy, as had many small- and medium-size

Argentine businesses. The ITSA strategy was to manufacture several Latin American countries also was considered. Based upon initial acceptance of the T-4 in the local market, products for the global market. In the face of falling tariff

barriers, MTs had to be produced with internationally compet- Turri increased its technical staff and opened its own U.S. distribution operation in California with the objective of ob-itive quality and prices. The new management concluded that

this could only be achieved through economies of scale that taining 1% of the large U.S. market (equivalent to four CNCs per month). To carry out this plan, a general manager, two were unattainable in the small and unstable domestic market.

At the time of its acquisition, Turri was a small business sales engineers, one service engineer, and a secretary were hired to staff the U.S. sales office, and several vehicles were compared with the other ITSA companies. It sold

approxi-mately 75 conventional and 12 numerically controlled lathes purchased. The new office required some US$45 thousand each month in start-up expenses, plus working capital to per year for total sales of under US$3 million. Total shares

outstanding were valued at US$1.5 million. maintain five machines in stock. Further outlays were required for participation in the Chicago and Milan international indus-Argentine industry’s reputation for protectionism and

lag-ging technology meant that the company had to make an extra trial trade fairs.

In 1986, Turri acquired another manufacturing licence effort to establish its credibility with world-class companies.

18

J Busn Res M. Paladino 2000:50:15–28Figure 2. Operating systems of parallel and CNC lathes.

faster T-2 CNC. Because of its high speed and low horsepower, three CNC lathe models (T-5, T-2, and T-1) and a lathe the T-2 was ideal for the specialty machining of small parts produced only through special orders, the TN-300.

and light alloys. However, it had limited sales potential in the Reflecting on Turri’s success in penetrating global markets Argentine market, where industrialists typically were looking during the 1982 to 1986 period, Mr. Gilligan felt that being for a general-purpose product. For example, the growing num- able to get those first licences required a lot of perseverence, bers of gearboxes required by the domestic automobile indus- given that to large international companies Turri didn’t have try contained steel parts that were forged and difficult to reasonable technological know-how to back up its intention machine on the T-2. of becoming a player in CNC equipment. Moreover, in those Meanwhile, Turri’s engineering department improved the years Argentina had a poor image, just emerging from military T-4 and turned it into a more technologically advanced prod- rule and heavily in debt. Regarding how Turri faced these uct: the T-5 CNC. It also developed the T-1 CNC, a unique circumstances, Mr. Gilligan remarked: “That is why we had model that was exhibited at the EMAQH 86, a prestigious to work so hard to reach an agreement with Takisawa, which international machine tool trade fair held in Buenos Aires was only one of many companies we had started negotiations every two years. This lathe, with a lower price and fewer with. We considered this agreement a key achievement to features, was developed to satisfy Turri’s traditional customer make Turri international.”

demand, the small- and medium-size workshops wanting to modernize without much investment. The EMAQH 86

coin-cided with the favorable results of a government initiative

The Manufacturing Process

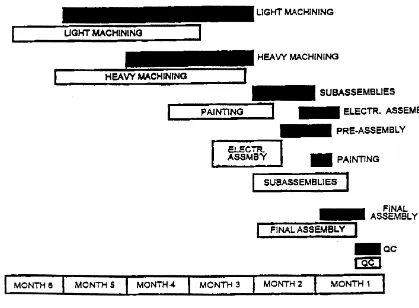

known as the Austral Plan to stabilize the economy, and thisTurri’s manufacturing process required close coordination combination of favorable factors produced a sales increase in

among the different areas involved in operations (see produc-the MT sector of 40 percent between June 1985 and April

tion planning flowchart, Figure 4). The process began with 1986. By 1990 Turri still offered a full line of parallel lathes

Figure 3. Planning area system.

agree on an annual production plan that included time re- There was no clear division at the plant separating the conven-tional and CNC product lines.

quired to source inputs.

This plan gave rise to a product program spanning a six- Each machine generally had one operator assigned to it that created an uneven workload. Some with light machine month time horizon as shown in Table 2 for both parallel

and CNC lathes. Activities included issuing production orders; loads tended to stretch times, while others were saturated with parts to be machined and became process bottlenecks. determining materials orders; scheduling machine loads at the

workshop; preparing a monthly estimate and a weekly load The production machinery in the Turri plants was not new but was generally in good condition. The most recent with day-to-day details; and supplying the subassembly and

final assembly sections. investment in equipment had been the purchase of a “machin-ing center” includ“machin-ing an entire system of machines from Man-The machining process for each part was detailed on

rout-ing sheets, which specified the operations to be performed delli of Milan, Italy, one of the world’s leading manufacturers of MCs. The cost had been US$800,000.

at the different machines indicated therein. All operations

required a previous machine setup task that typically took a All castings and fairing component plates were painted in one area. Since a customer could choose among lathe colors, long time. For this reason, machining of parts was done in

re-20

J Busn Res M. Paladino 2000:50:15–28Figure 4. Manufacturing timetable.

works or those made due to changes requested by customers In the case of exports, lathes were packed in wooden crates assembled at the carpentry section. Every lathe was shipped were quite frequent. The facilities were a bit old and demanded

special manual labor and care on the part of supervisors and with a series of normal and special accessories that were added at this stage.

painters.

The process was basically the same for parallel lathes, ex-The next stage was the assembly of the different

subassem-cept for preassembly, which took place before painting (refer blies that went into the product, which were subsequently

to Table 2). However, an internal report analyzing the impact sent to final assembly. They were put together according to

on operations of the discontinuation of parallel lathe manufac-an assembly order (AO) in series of four to six subassemblies.

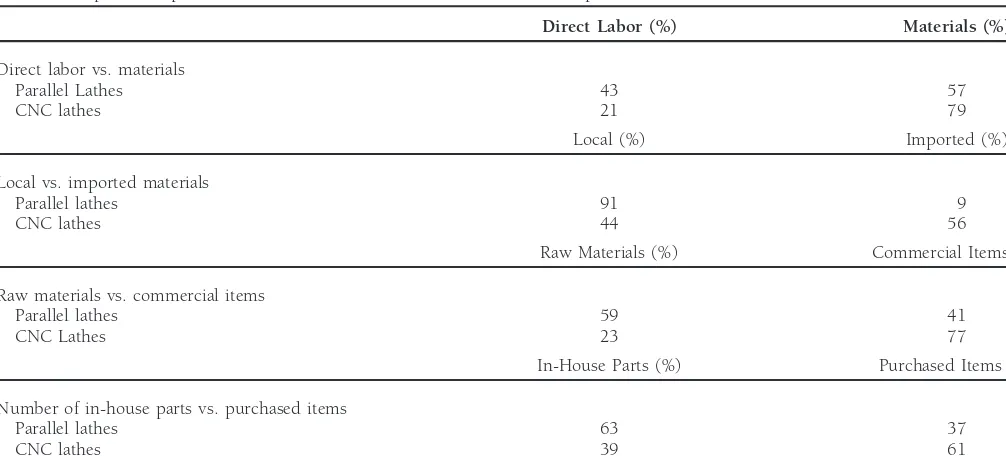

ture had shown that CNCs were less labor intensive, required Warehouses would release materials on the basis of AOs.

more imported materials and purchased items, and could use The different subassemblies were mounted in succession

fewer in-house parts (see Figure 5). on top of the lathe base or bed, while lathe plating or fairing

was being built. Simultaneously, electric wiring and general machine cabling was carried out, as well as installation of all

Human Resources

lathe servomotors and hydraulic connections. This requiredoperators with different skills working together. Front-line workers were affiliated with the traditional and Finally, the entire machine performance and quality specifi- strong Metallurgical Industrial Union (UOM), while supervi-cation conformance were verified. Quality control was the sors belonged to the ASIMRA union. Due to a company policy responsibility of a boss and two supervisors who originally of international promotion, all supervisors had been promoted reported to the engineering department. Quality control man- from operator positions. They possessed a thorough knowl-agement basically was done at three stages: (1) inspection of edge of their tasks and were closely acquainted with their main castings, (2) control of parts machined in-house at the subordinates, many of whom had been their peers.

Table 2. Impact on Operations of Parallel Lathe Discontinuation: Internal Report

Raw Materials (%) Commercial Items (%)

Raw materials vs. commercial items

Parallel lathes 59 41

CNC Lathes 23 77

In-House Parts (%) Purchased Items (%)

Number of in-house parts vs. purchased items

Parallel lathes 63 37

CNC lathes 39 61

pany for over 20 years, quite often sharing strong friendship had gone down in price as a result of technological break-throughs and larger scale production, particularly in Japanese and even family ties. They earned a fixed wage and an

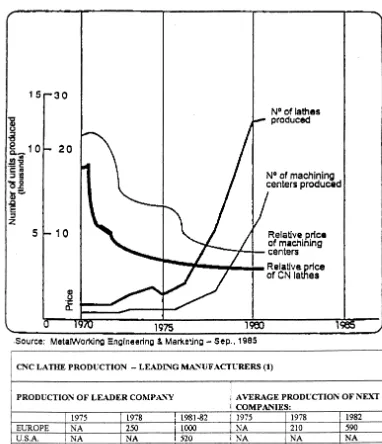

individ-ual bonus. Each operator’s bonus depended on productivity, companies (see Table 3).

High-tech MT production thus was clustered in relatively as measured by predetermined time standards for each

opera-tion. When the task did not have any predetermined time estab- few countries, with exports as the primary means of interna-tional expansion. Technology transfers and direct foreign in-lished or if, for any reason, the standard could not be met,

the supervisor used his judgment in applying the percentage vestment also had been used, although to a smaller degree, in expanding the industry.

production bonus. The maximum bonus rate was 33% of salary,

although people would typically receive 30% as an average. Typically, MTs were produced in lots or short runs because of the wide variety of accessories needed for different machin-ing operations. In Latin America, only Argentina and Brazil

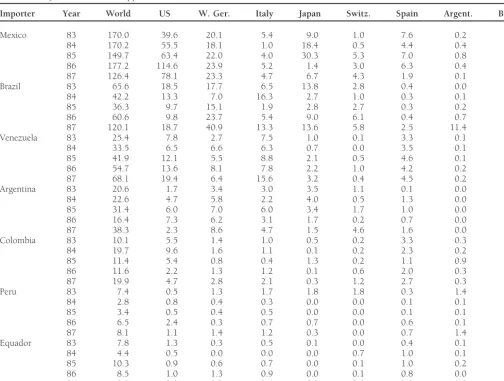

The Industrial Sector

had a significant production. Table 4 provides data on MT supplier to major countries in the region through 1987. Incipi-Machine tool manufacturers had typically been small andent growth in MT industry trade between Brazil and Argentina medium sized; although in such countries as Japan, Brazil, and

has occurred since then as a consequence of having including South Korea, the role of big firms was becoming increasingly

MTs in the common list of Protocol No. 1 on Capital Goods important. MTs made up a small fraction of capital goods

(an economic integration program agreed upon by both na-production. Nevertheless, this industry was considered to be

tions for selected industrial sectors). important because of its contribution to technological

develop-In 1990, Japan was the world’s largest producer of MTs, ment. The MT industry acted as a transmission belts for

techno-having taken the lead from the United States. European manu-logical innovations to downstream industrial sectors, and

pro-facturers held their ground and some emerging economies, ducer countries usually had schemes in place to protect it.

such as China, Taiwan, India, and Korea, consolidated their Few participants in the MT industry had the capacity to

positions. both design and produce. Technological evolution had changed

the research and development (R&D) function and its

eco-nomic relevance. Thus, R&D teams would require increasing

Local Industry

numbers of electronic technicians, and from being a minorexpense, R&D came to consume approximately 5% of sales With the development of the Argentine automobile industry, MT demand reached its heyday in the early 1970s. In 1973, revenues in leading companies. The market was aware of this,

primarily through international trade fairs, where potential total production was 22,500 units employing 6,000 people, and the market was dominated by small- and medium-size buyers examined new products and evaluated new industry

22

J Busn Res M. Paladino 2000:50:15–28Figure 5. Technological development and NCMT prices in Japan.

levied on imported products, following the traditional import to those manufactured locally were able to enter the country through the so-called lump tariff items in the tariff schedule. substitution model of industrial development.

Economic liberalization policies introduced in 1976 had a In 1985, a resolution (P78) adopted by the Secretariat of Industry and Commerce accorded tariff protection to domesti-devastating impact on local industry, especially overwhelming

between 1980 and 1982. Few producers survived, and by cally manufactured CNC lathes of 95%, subsequently reduced to 50% in 1990. At the same time, imported numerical control 1990 only local two companies, Turri and Promecor, were

capable of competing in world markets. These were the only units would be subject to a higher tariff to favor local produc-tion. Resolution P78 was thought to provide greater protection Argentine companies to have incorporated CNC technology,

which was of rapidly growing importance in the local market than requested by NCMT manufacturers themselves. (as shown in Table 5).

Tariff protection for CNC lathes (first 35% and then 45%)

Relaunching Turri—1986

made it possible for local producers to successfully competeTable 3. Major Machine Tool Suppliers to Latin American Markets (millions of US$)

Importer Year World US W. Ger. Italy Japan Switz. Spain Argent. Brazil

Mexico 83 170.0 39.6 20.1 5.4 9.0 1.0 7.6 0.2 0.6

major transformation process undertaken by new manage- would command US$85,000 Brazil, whereas a Brazilian machine similar to ours would cost over US$160,000. ment and supported by the board of directors. Within six

months, most of the positions had been filled by younger

In 1985, before the Brazilian door opened, the company managers, though the production management team had been

had been able to export only 12 CNCs against expected export the most difficult to replace.

sales of 36, and it had been able to do so only by reducing At that time, Turri had the opportunity to enter the

Brazil-its price to US$80,000, less than similar Japanese machines. ian market, which was ten times larger than the domestic

Currency devaluation and low labor costs helped to sustain market. Under Protocol No. 1 on Capital Goods, doors were

this price reduction, as did pressures from a new domestic opening to Argentine products within the framework of

Argen-competitor, Promecor. tina-Brazil economic integration promoted by former

Presi-The domestic market began to grow once again during dent Alfonsı´n. Turri’s CEO commented,

1987 and the first quarter of 1988, at the same time that the Brazilian market was opening to Argentine products. Turri The opportunity of entering Brazil arose from the fact that

they were lagging some six years behind in CNC machines, was unable to take advantage of these market opportunities, however, because of its inability to make on-time deliveries, to because their computer information law banned control

unit imports. On the other hand, since it was a closed provide after-sale service, and to ensure the quality of its prod-ucts. Problems began with in-bound logistics: there were short-market, we were able to sell at higher prices. For example,

24

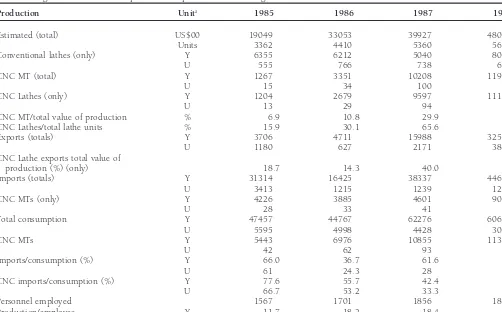

J Busn Res M. Paladino 2000:50:15–28Table 4. Argentine Production, Exports, and Imports of Metalworking Machine Tools (thousands of US$ and units)

Production Unita 1985 1986 1987 1988

Estimated (total) US$00 19049 33053 39927 48023

Units 3362 4410 5360 5639

Conventional lathes (only) Y 6355 6212 5040 8035

U 555 766 738 673

CNC MT (total) Y 1267 3351 10208 11934

U 15 34 100 95

CNC Lathes (only) Y 1204 2679 9597 11181

U 13 29 94 90

CNC MT/total value of production % 6.9 10.8 29.9 28.4

CNC Lathes/total lathe units % 15.9 30.1 65.6 48.2

Exports (totals) Y 3706 4711 15988 32590

U 1180 627 2171 3818

CNC Lathe exports total value of

production (%) (only) 18.7 14.3 40.0 67.0

Imports (totals) Y 31314 16425 38337 44648

U 3413 1215 1239 1229

CNC MTs (only) Y 4226 3885 4601 9014

U 28 33 41 40

Total consumption Y 47457 44767 62276 60681

U 5595 4998 4428 3050

CNC MTs Y 5443 6976 10855 11354

U 42 62 93 59

Imports/consumption (%) Y 66.0 36.7 61.6 73.6

U 61 24.3 28 40.3

CNC imports/consumption (%) Y 77.6 55.7 42.4 79.4

U 66.7 53.2 33.3 67.8

Personnel employed 1567 1701 1856 1870

Production/employee Y 11.7 18.2 18.4 22.5

aUnit: Y (thousands of dollars); Units: U.

led to bottlenecks in production flows and huge work-in- since this type of machine is “sold by the pound” and process inventories. Information systems broke down; front- competition was focused on producing them on a large line workers refused to cooperate and threatened to strike. scale, with low labor and raw material costs. We were These operating problems produced heavy financial losses already seeing that we could not compete against the Chi-that were made worse by the expensive financing of increased nese and Taiwanese in this segment.

working capital needs. In the 1987–88 period, an estimated

The environment of hyperinflation and severe recession in US$5 million had been poured into Turri by ITSA to replenish

Argentina during most of 1989 accentuated the crisis. The working capital. Finally, in late 1988, ITSA withdrew its

finan-payroll was continuously reduced, and the objective came to cial support and demanded changes, including the closing of

be mere survival. Nevertheless, some achievements were made Turri’s distributor in California.

in the 1989–90 period. Mr. Gilligan commented that, Meanwhile, the economic stabilization plan that had been

introduced three years earlier was floundering. The govern- Despite all the operating problems, product quality and ment launched the “spring plan,” which fixed the exchange after-sale service had improved since 1987 and CNC lathes rate for a few months but did not curb inflation. As a result, were more reliable. The development of a Latin American Turri started losing money on exports. “It seemed incredible, trade network and Turri’s brand name positioning in the but between August 1988 and January 1989, the more we CNC lathe segment are also worth mentioning.

exported, the more we would lose,” remarked the CEO.

None-In mid-1988, the company had 230 employees organized theless, between February and July, Turri recuperated

sub-in a functional structure. By September 1990, the number of stantially from earlier losses, due to increased exports to Brazil,

employees had been cut to 80. The CEO commented, which accounted for 70% of company sales. But despite the

momentum of this reactivation, the company continued to

As we improved we saw that our plant was obsolete and sell few numerically controlled and many parallel lathes. Mr.

that heavy investments had to be made in processes. With Gilligan explained,

Table 5. Production, Exports and Imports of Machine Tool for Metals Working in Argentina (in Thousands of Dollars and units)

Unita 1985 1986 1987 1988

Production

Estimated Y 19049 33053 39927 48023

U 3362 4410 5360 5639

NAMTMb Y 18364 30960 34180 42000

U 2593 4170 4446 2763

Conventional lathes Y 6355 6212 5040 8035

U 555 766 738 673

CNC MT Y 1267 3351 10208 11934

U 15 34 100 95

CNC Lathes Y 1204 2679 9597 11181

U 13 29 94 90

CNC MT/Total production % Y 6.9 10.8 29.9 28.4

CNC Lathes/Total lathesc% Y 15.9 30.1 65.6 48.2

Exports

Totals Y 3706 4711 15988 32590

U 1180 627 2171 3818

Exports/production % Y 18.7 14.3 40.0 67.0

CNC Lathes Y 50 260 3954 9594

U 1 5 38 77

Exp./Prod. CNC lathes % Y 4.2 9.7 41.2 85.8

Imports

Totals Y 31314 16425 38337 44648

U 3413 1215 1239 1229

CNC MT Y 4226 3885 4601 9014

U 28 33 41 40

Consumption

Total Y 47457 44767 62276 60681

U 5595 4998 4428 3050

CNC MT Y 5443 6976 10855 11354

U 42 62 93 59

Imports/Consumption % Y 66.0 36.7 61.6 73.6

U 61 24.3 28 40.3

Imports/CNC consumption % Y 77.6 55.7 42.4 79.4

U 66.7 53.2 33.3 67.8

Personnel employed U 1567 1701 1856 1870

Production/employees Y 11.7 18.2 18.4 22.5

Source: production estimated with the production function of the NAMTM partners and export data from INDEC (National Statistics Office). aUnit: Y (thousands of dollars); Units: U.

bNational Association of Machine Tools Manufacturers.

cProduction, in thousands of dollars, of conventional and CNC lathes.

just the beginning. Entering first-class markets without producer of computerized machining centers (US$400 million machines that guarantee manufacturing precision is very annual sales) and a Turri supplier. Mr. Mandelli agreed in difficult. Unfortunately the company is not now in a finan- principle to a joint venture agreement to establish a 1.2 million cial position to make these investments. square–foot factory for the manufacture of numerically con-trolled machining centers and flexible manufacturing systems One expansion alternative had been a US$60-million

proj-for the Latin American market. However, the project was ect to set up a lathe factory in Neuque´n, some 1,300 kilometers

abandoned when newly elected president Carlos Menem en-from Buenos Aires. This expansion, approved during the

Al-acted the Economic Emergency Act suspending industrial pro-fonsin administration, was to be made under the Argentine

motion and, hence, the Neuque´n project. government’s industrial promotion and economic

develop-ment plan, with the support of Italian governdevelop-ment credit. The

idea was to get Takisawa interested, but despite months of

Alternatives for the Future—1990

urging by Turri’s CEO, the Japanese company did not seemAs globalization became a reality and international competi-so inclined.

tion became more intense, the benefits of bilateral agreements During a trip to Italy, Mr. Gilligan presented the project to

26

J Busn Res M. Paladino 2000:50:15–28realized that it was imperative to find a way of truly becoming industry undergoing rapid technological change. The case an international company, beyond regional agreements tem- describes acquisition by a Swiss multinational and later by porally covered by government negotiations: an Argentine conglomerate, technological agreements with a small Japanese manufacturer, and presents a possible joint We thought if these countries stabilized and grew they

venture with an Italian supplier. would provide opportunities for international businesses

Teaching objectives include: to try and introduce their products, the capital goods

needed for growth. And some would even think of estab- 1. Identifying the key factors in the success of a new ven-lishing plants closer to their customers. ture. The multipurpose parallel lathe produced by the Italian immigrant could be used in a wide variety of In these circumstances we were wondering how we could

industrial applications by small business in Argentina, turn these potential risks of intense international competition

making it the right product in the right place at the right into opportunities, considering our weakness in competing

time. Moreover, the pride of craftsmanship ensured that just as Turri in an increasingly demanding market. We were

high quality standards would be adhered to and the aware of our weaknesses, but we also had strong points we

personalized attention meant that customer loyalty could take advantage of: a good Latin American commercial

would be obtained. network; an improved after-sale service level; a prestigious

2. Evaluating the impact of environmental factors on per-brand name in the CNC lathe segment; credibility because

formance. The economic swings and policy changes Turri continued to serve its customers despite the crisis; and

made it difficult to chart a long-range export strategy, the possibility of benefiting from the comparative advantages

but in general it was the internal problems that accom-the country offered this product: qualified professionals and

panied the evolution of this small entrepreneurial com-labor that could be easily trained at a relatively low cost.

The alternative of giving up the MT business and commit- pany evolves into a large formal structure, rather than ting efforts and resources to other more profitable activities the problems of the external environment, that led to available to the group met with resistance. That’s why we had missed opportunities in Brazil and elsewhere.

to find a way to go on: for a firm like Turri, it now seemed 3. Analyzing sources of competitive advantage. Each suc-impossible or at least difficult to continue by ourselves, as it cessive owner brought distinctive advantages to Turri: had been in the last eight years, when we had invested in the Swiss brought the first numerically controlled ma-machinery, technology, management, new market develop- chines, giving the company a first mover advantage in ment, and all sorts of adjustments and rationalizations to the local market and helping to make the first exports. compete internationally. ITSA brought capital, contacts, and the strategy of

seek-In September 1990, Mr. Gilligan met once again with Mr. ing technological agreements abroad.

Mandelli during the Chicago international MT fair. From this 4. Negotiating international alliances. The case can be used meeting came the renewed possibility of working together in to stage a simulated negotiation with Mandelli for a Latin America. The European manufacturer did not anticipate joint venture in Argentina.

acquiring a new business but rather suggested creating an

This case may be used in a masters’ level course in corporate industrial plant with a modern machinery pool and model

strategy, in the section dealing with the formulation of a rationalization. It would include the addition of a machining

technology policy or with the creation of international alli-center line to the CNC lathe product line. The new joint

ances. It might be accompanied by a reading on strategic venture would initially concentrate operations in the Latin

alliances (e.g., Badaracco, 1992). American market before proceeding to gain access to the rest

of the world.

Upon returning to Argentina, Mr. Gilligan wondered how to proceed with the negotiations. The CEO saw many

ques-tions arising: what advantages would have to be protected?

Suggested Questions for Discussion

Should most management be given up? What kind ofpartner-ship would be the most convenient? He believed that these 1. What is your assessment of Turri’s decision to discon-many concerns would require developing a detailed action tinue the manufacture of parallel lathes?

plan to guide future decisions. 2. What did the Swiss bring to Turri, and why did they sell? What did the ITSA group bring?

3. How successful was the “relaunching” of Turri in 1986?

Teaching Note

Why?

Case Purpose and Teaching Objectives

4. What are your recommendations to the CEO, Mr. Gilli-gan, regarding the upcoming negotiation with Giancarlo The purpose of this case is to understand the strategicpointed with the company’s performance, but there is no

Case Analysis

evidence to support this conclusion.

What is Your Assessment

ITSA, the Argentine conglomerate, was in a better positionof Turri’s Decision to Discontinue

to understand the national economic and politicalenviron-the Manufacture of Parallel Laenviron-thes?

ment. It could provide contacts and resources. It also recog-nized its technological limitations (ITSA had no experience This question opens a discussion of the current problemsin the machine tool industry; it was largely in energy and facing Turri, and their causes. The first part of this discussion

transportation) and encouraged Turri to seek agreements with involves the changing machine tool market and the rapid

technology leaders in Japan. obsolescence of traditional, parallel lathes and their

replace-ment by CNCs. Support for this conclusion can be found in the data on the Argentine machine tool industry (Table 5), in

How Successful Was the

which CNC lathes increased from 15.9% of the units produced

in 1985 to 48.2% in 1988. Domestic sales and exports of parallel

“Relaunching” of Turri in 1986? Why?

lathes by Turri also are decreasing rapidly (Table 1). The relaunching was a disaster. This is difficult to understand A second justification for the discontinuation of parallel after four years of ITSA ownership in which sales both tradi-lathes is in gaining production efficiency and reducing costs tional and CNC lathes had been built up. The problem was through a reduced product line. Turri sold a wide variety of that Turri was unable to deliver. Of the 73 CNC lathes sold parallel lathes, whereas it is now concentrating production in export markets during 1987 and 1988, only 48 were deliv-on deliv-only three CNC models. Moreover, the productideliv-on pro- ered by the end of 1988. As a consequence, sales fell in both cesses are very different for the two types of lathes, both in 1989 and 1990. (See Table 1).

terms of scheduling (Table 2) and in terms of the mix of inputs One hypothesis is that Turri simply was unprepared to go required (Figure 5). Parallel lathes are less labor intensive, from production volumes of around 40 CNC lathes per year meaning the prospect of worker layoffs, but they more im- to 60–70 CNC lathes per year. Because of the significantly ported materials and more outsourcing. different production technologies involved, it was not possible A third justification is that the CNC machines are greater to simply substitute CNC production for parallel lathe produc-revenue earners, selling at a price of 90,000 versus only 12,000 tion. Still, the company should have been able to keep pace for the average parallel lathe. Consequently, Turri was able with the demand.

to maintain and even increase dollar volume of sales through A more plausible explanation for the quality problems and 1989 despite declining unit sales. Therefore, the decision failure to meet deadlines may be found in the organizational seems justified from several perspectives.

disarray caused by the older managers’ reactions to the re-However, the decision has had an adverse impact on the

launching. Incredibly, the case states that all managers with company’s finances. Though we do not have the financial

over 15 years’ experience in the company presented their statements, the CEO makes reference to the current liquidity

resignations. Though most were soon replaced with younger crisis in late 1990. Given the dramatically higher content of

managers, we might ask whether these had the requisite expe-imported materials in CNC lathes (56% versus 9%) and the

rience and contacts in the machine tool industry, or whether need to keep five on hand in the California sales office, it can

they were brought from the ranks of ITSA’s other companies. be concluded that the working capital requirements of the

Moreover, we are told that the production team was the most new strategy are much greater than with the production of

difficult to replace. Clearly, the organizational turmoil had parallel lathes.

taken its toll.

What did the Swiss Bring to

What Are Your Recommendations

Turri, and Why Did They Sell?

to the CEO, Mr. Gilligan, Regarding the

What Did the ITSA Group Bring?

Upcoming Negotiation with Giancarlo Mandelli?

It was the Swiss who first introduced numerically controlled

By 1990, the negotiating position of Turri had been weakened lathes in Turri, though it can be argued that these basically

by its poor service to clients and its precarious liquidity posi-consisted of retrofitting converted parallel machines with CNC

tion. Its strong points continue to be a prestigious brand name units. The Swiss also implemented a state-of-the-art

technol-in the CNC lathe segment; technology, both acquired from ogy policy and invested significant amounts in R&D. However,

Japan and developed locally; market position; and a distribu-they were unprepared for the economic shocks of the early

tion network within Argentina and surrounding countries. 1980s and preferred to sell rather than bet on Argentina’s

28

J Busn Res M. Paladino 2000:50:15–28Turri’s machine tools are complementary with Mandelli’s ma- exchange for participation in the venture, or it must negotiate chine centers, so that a marketing and distribution alliance in financing with ITSA.

Argentina and surrounding countries makes sense. However,

Turri is not in a financial position to invest in a new industrial

Reference

plant for the pooling of a machining center line with a CNC Badaracco, Joseph L.:Alianzas Estrate´gicas, McGraw Hill, New York.

1992.