International Review of Economics and Finance 8 (1999) 421–431

The value of financial outside directors on

corporate boards

Yung Sheng Lee

a,*, Stuart Rosenstein

b, Jeffrey G. Wyatt

c aCitibank, SingaporebUniversity of Colorado at Denver, Graduate School of Business Administration, Campus Box 165,

P.O. Box 173364, Denver, CO 80217, USA

cDepartment of Finance, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056, USA

Received 8 January 1998; accepted 24 September 1998

Abstract

The appointment of a financial outside director to the board of a public corporation is associated with positive abnormal returns, attributable entirely to the smaller than median-size firms in our sample. In addition, investment bankers are appointed to the boards of much smaller companies, on average, than commercial bankers or insurance executives. These results suggest that smaller firms, which may have limited access to financial markets and less financial expertise, benefit substantially from these appointments. 1999 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved.

JEL classification:G30

Keywords:Corporate governance; Board of directors

1. Introduction

Although a growing number of empirical studies find support for the value of outside directors, there is little research into the value of outside directors relative to their specific occupations or types of experience. In this article, we focus on outside directors recruited from different types of financial institutions. We examine the share price reaction to announcements of the appointment of financial outside directors.

Fama and Jensen (1983) claim that outside directors can add value both as monitors of management and providers of “relevant complementary knowledge” (p. 315).

How-* Corresponding author. Tel.: 303-556-6518; fax: 303-556-5899.

E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Rosenstein)

ever, there is some disagreement with respect to the value offinancialoutside directors. While Easterbrook (1984) contends that contributors of capital are very good monitors of management, Brickley et al. (1988) claim that most financial outside directors are drawn from organizations that are sensitive to pressure from management and, therefore, may not be independent in their judgments. Evidence by Rosenstein and Wyatt (1990) indicates that the addition of an outside director who is an officer of a financial firm increases shareholder wealth. However, Rosenstein and Wyatt (1990) treat all financial outside directors as a homogeneous group.

In this article, we contend that commercial bankers, insurance company executives, and investment bankers are heterogeneous groups, bringing different types of expertise and reputational capital to boards of directors. Thus, we examine whether there are differential share price reactions associated with appointments of outside directors from each of these groups. As in Rosenstein and Wyatt (1990), we find that the appointment of a financial outside director to the board of a public corporation is associated with positive abnormal returns. We cannot reject the hypothesis that abnor-mal returns are equal across the three groups.

More importantly, abnormal returns are significantly positive for firms that are below the median market value of our sample, suggesting that small firms, which have less access to financial markets and less financial expertise, benefit substantially from the addition of a financial outside director to their boards. For the smaller firms, we find that abnormal returns are significantly positive for both commercial bankers and investment bankers, but not for insurance company executives. In addition, we find that firms that add investment bankers are much smaller, on average, than those that add commercial bankers or insurance company executives.

The article is organized as follows: We first discuss prior research and then develop testable implications. The data collection procedure and empirical methods are then outlined. Empirical results are presented, and finally, conclusions are drawn.

2. Prior research

The corporate governance literature indicates that the composition of the board of directors is an important element in protecting the interests of shareholders, espe-cially in cases of transactions where the interests of managers and outside shareholders may diverge.1A number of studies have also examined the value of outside directors

under ordinary business conditions, when there is no publicly disclosed important corporate control transaction occurring. For example, Rosenstein and Wyatt (1990) found that the appointment of an outside director results in a significant increase in firm value. However, Bhagat and Black (1997) found that the proportion of independent directors is unrelated to future performance.

Several studies examine the characteristics of outside directors other than their specific occupations. For example, Kosnik (1990) found that a firm is more likely to pay greenmail when the outside directors come from diverse backgrounds, perhaps indicating that a fragmented board is less able to ensure that management and share-holder interests are closely aligned. Shivdasani and Yermack (1997) assert that the number of other outside directorships held by independent directors is important in determining their value to the firm. Although several other outside directorships will be looked on as an indication of high quality, independent directors with more than three additional directorships may be viewed as being too thinly spread to be effective. Shivdasani and Yermack show qualitative evidence to support this claim. Brickley et al. (1994) found that on the adoption of a “poison pill,” the proportion of the board that are “professional directors” (i.e., retired business executives and those who list their occupation as being a director) has a large positive influence on abnormal returns. With respect to financial outside directors, Rosenstein and Wyatt (1990) find that appointments of financial outside directors are associated with significantly positive abnormal returns. However, they cannot reject the hypothesis that outside directors from financial corporations, nonfinancial firms, or other occupational backgrounds have a differential effect on firm value.

Booth and Deli (1997) studied the characteristics of firms that have financial direc-tors, finding that firms with a financial outside director have more debt than those without a financial outsider. They then provided evidence consistent with the theory that financial outside directors provide expertise to the firms on whose boards they sit, and not as a means of monitoring a business relationship.

In summary, the literature suggests that the financial markets discriminate among outside directors by their occupations and experience. In addition, there is some evidence that financial outside directors have a specific value to corporations, setting the stage for an examination of valuation effects as a function of the type of financial firm from which financial outside directors are drawn.

3. Testable implications

Financial directors are expected to provide specific types of knowledge to corporate boards. All three of the categories we examine—commercial bankers, insurance com-pany executives, and investment bankers—have intimate and timely knowledge of conditions in the financial markets, and they should be able to provide management with general information regarding the least costly and most prudent method of acquiring long-term or working capital.

in their roles as appraisers of credit worthiness. The appointment of a commercial banker or insurance company executive may serve to reduce agency costs between creditors and shareholders, increasing firm value. Our first hypothesis, then, is that there is a significantly positive wealth effect associated with the appointment of a financial outside director to the board of a public corporation.

This article builds on previous research by examining the relative valuation effects of the three different types of financial directors. This examination is exploratory in nature because there is little in the way of past empirical or theoretical work to guide hypotheses with respect to relative valuation effects. Brickley et al. (1988) characterize all three groups as “pressure-sensitive,” meaning that the potential for business rela-tionships with the firms on whose boards they sit may cause these directors to be less than arm’s length monitors of management performance. This pressure, along with the more complete understanding of the companies gained as a result of their serving on the board, may result in lower financing costs.

As experts in credit analysis, commercial bankers and insurance company executives on the board might also be expected to mitigate agency problems between shareholders and creditors. Investment bankers, on the other hand, are associated with both debt and equity issues, and also with acquisition activity. While their expertise might be valuable, there is little reason to expect that they would mitigate agency costs more or less than any other outside director. In the absence of a more complete theory, we make no predictions with respect to the relative valuation effects of appointments of these three types of financial director.

Directors are rarely recruited from pressure-resistant organizations (public pension funds, mutual funds, endowments, and foundations owning at least 1% of the firm’s stock; see Brickley et al., 1988), either because of legal restrictions, tradition, or because corporate managements do not want them on their boards. Therefore, we cannot test the relative wealth effects of appointments of pressure-sensitive versus pressure-insensitive financial outside directors.

Our second testable hypothesis is that wealth effects associated with the appointment of a financial outside director are inversely related to firm size. It is generally recognized that small firms have less access to financial markets than do large firms and are less likely to be covered by securities analysts. In addition, small firms are less likely to be able to support the necessary staff personnel to maintain expertise in all forms of financial dealing. Thus, the appointment of a financial director to the board may be more valuable for small firms than for large firms. Again, we make no predictions with respect to relative valuation effects across the types of financial directors.

4. Data and methodology

4.1. Sampling procedure

An outside director is defined as a director who is not a present or past employee of the firm and whose only formal connection with the firm is his or her duties as a director. Board members whose appointments are directly attributable to ownership of shares in the corporation, either directly or as agents, are excluded from the sample. The initial data set includes all of the Wall Street Journal’s “Who’s News” announcements of the appointment of only one outside director and no inside directors over the 1981–1985 period. Firms in the sample also must have returns available on

theCRSP Daily Stock Returndatabase. This selection criteria is used to remove two

potential biases. First, the appointment of several directors may signal a significant change in strategy, which may result in confounding abnormal returns. Second, the appointment of an inside director may signal that the CEO is planning to step down, and might also result in confounding abnormal returns.

The data set is further refined using the following criteria:

1. Announcements are eliminated if the news item is contaminated by information about corporate personnel changes, merger, or other activity.

2. Announcements are eliminated if there areanymissing returns over the period from 170 days before through 20 days after the announcement. Missing returns may indicate a halt in trading occasioned by a major event such as merger or bankruptcy that may result in changes to the board.

3. Announcements are eliminated if inspection of SEC 13D filings indicate that newly appointed directors, or the entities with which they are affiliated, hold a 5% or greater ownership stake in the sample firm. This step is taken to eliminate director appointments that were likely to have been initiated by shareholders. Rosenstein and Wyatt’s (1990) final sample contains 1,251 announcements. Of these, 217 are financial outside directors, including individuals from the following types of firms: commercial banks, insurance companies, investment banks, fund managers, savings and loans, venture capital firms, and other unclassified financial firms. An-nouncements then are eliminated if categories overlap (for example, fund managers are often associated with brokerage houses having investment banking departments) or where the appointee’s occupation could not be clearly categorized. Because the resulting sample contains very few directors who were not employees of commercial banks, insurance companies, or investment banks, the final sample concentrates solely on those three categories. The final data set contains 146 announcements of the appointment of an outside director from a commercial bank, insurance company, or investment bank.

4.2. Sample characteristics

commer-Table 1

Characteristics of a Sample of 146 Announcements of the Appointment of an Outside Financial Director to the Board of a NYSE or AMEX Corporation as Reported in theWall Street Journal“Who’s News” Section over the Period 1981–1985

A. Frequency distribution of announcements by year

1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 Total

Frequency 29 26 34 41 16 146

(%) (19.8) (17.8) (23.3) (28.1) (11.0) (100)

B. Frequency distribution of announcements by month

Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May June

Frequency 12 17 12 15 21 7

(%) (8.2) (11.6) (8.2) (10.3) (14.4) (4.8)

July Aug. Sep. Oct. Nov. Dec.

Frequency 13 11 6 14 11 7

(%) (8.9) (7.5) (4.1) (9.6) (7.5) (4.8)

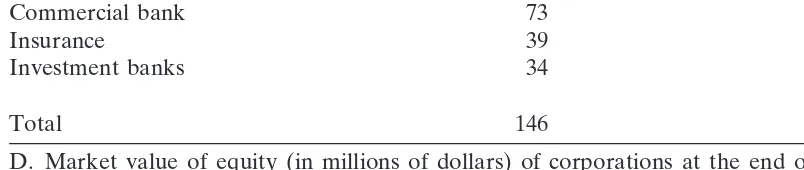

C. Frequency distribution of announcements by directors’ primary occupations

Employer type Frequency % of total

Commercial bank 73 50.0

Insurance 39 26.7

Investment banks 34 23.3

Total 146 100.0

D. Market value of equity (in millions of dollars) of corporations at the end of the month preceding the announcement

Number of Mean market

announcements (%) value Smallest Median Largest

Commercial bank 73 (50.0) 1762.4 6.9 460.3 14535.2

Insurance 39 (26.7) 1733.8 18.6 651.8 8187.7

Investment bank 34 (22.3) 305.9 4.1 144.3 1360.9

Total 146 (100.0) 1415.6 4.1 387.6 14535.2

cial bankers comprise 50.0% of the sample, with the remainder roughly equally divided between investment bankers and insurance company executives.

It is important to note that, on average, investment bankers are named to the boards of much smaller firms than commercial or investment bankers (panel D). The median (mean) market value of equity for firms that appoint investment bankers is just $144.3 ($305.9) million, significantly lower than the median (mean) market values of $460.3 ($1,762.3) million for commercial bankers and $651.8 ($1,733.8) million for insurance company executives.2One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that

Table 2

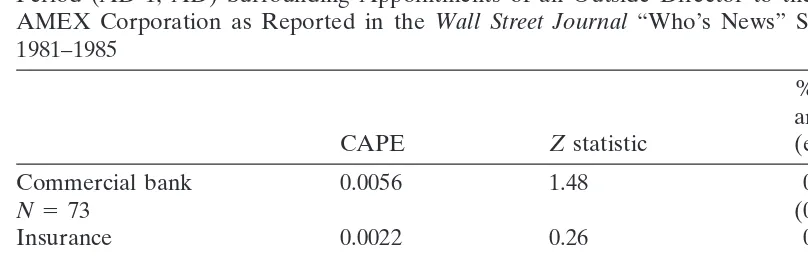

Cumulative Average Prediction Errors (CAPE) and Test Statistics for the Two-day Announcement Period (AD-1, AD) Surrounding Appointments of an Outside Director to the Board of a NYSE or AMEX Corporation as Reported in the Wall Street Journal“Who’s News” Section over the Period 1981–1985

% positive over two-day announcement period

CAPE Zstatistic (estimation period)

Commercial bank 0.0056 1.48 0.59b

N573 (0.48)

Insurance 0.0022 0.26 0.46

N539 (0.48)

Investment bank 0.0039 1.19 0.53

N534 (0.48)

Total 0.0048 1.73a 0.53

N5146 (0.48)

aStatistically significant at the 0.10 confidence level (two-tailed test). bStatistically significant at the 0.10 level for the standard test of proportions.

4.3. Statistical methods

The announcement date (AD) is defined as the date that the announcement appears in the “Who’s News” section of theWall Street Journal.Standard event study methodol-ogy is used to measure abnormal returns. The market model is used for parameter estimation, with the 150 trading day period (AD-170, AD-21) used as the estimation period and theCRSPequally weighted index serving as the market index. The analysis focuses on the 2-day announcement period (AD-1, AD). See Furtado and Rozeff (1987) for a concise description of the method.

Two statistics are used to test the significance of prediction errors, the traditional parametric test statistic based on the 2-day cumulative standardized prediction error3

(CSPE), and the binomial test that the proportion of abnormal returns over the 2-day announcement period is different than the proportion of abnormal returns over the estimation period.

5. Empirical results

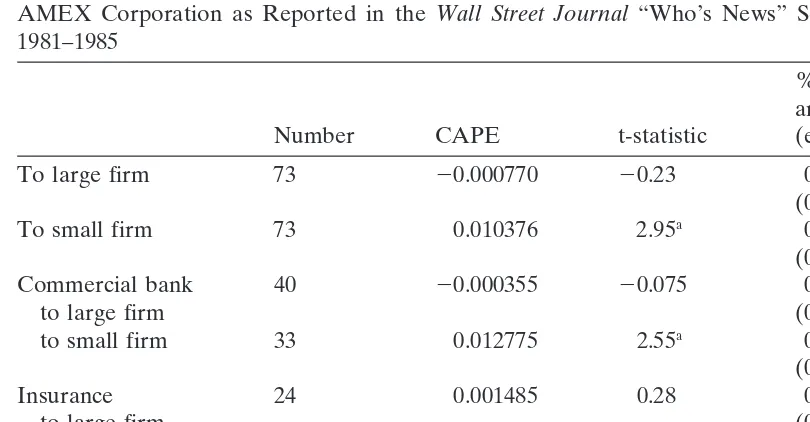

Table 3

Cumulative Average Prediction Errors (CAPE) and Test Statistics for the Two-day Announcement Period (AD-1, AD) Surrounding Appointments of an Outside Director to the Board of a NYSE or AMEX Corporation as Reported in the Wall Street Journal“Who’s News” Section over the Period 1981–1985

% positive over two-day announcement period

Number CAPE t-statistic (estimation period)

To large firm 73 20.000770 20.23 0.49

(0.48)

To small firm 73 0.010376 2.95a 0.59b

(0.48)

Commercial bank 40 20.000355 20.075 0.55

to large firm (0.48)

to small firm 33 0.012775 2.55a 0.64b

(0.48)

Insurance 24 0.001485 0.28 0.42

to large firm (0.49)

to small firm 15 0.003284 0.52 0.53

(0.47)

Investment bank 9 20.008625 20.86 0.44

to large firm (0.48)

to small firm 25 0.011464 1.65 0.56

(0.47)

“Large” refers to firms that have greater than the median market value of equity at the end of the month preceding the announcement for the sub-sample in question.

aStatistically significant at the 0.05 confidence level (two-tailed test). bStatistically significant at the 0.10 level for the standard test of proportions.

In Table 3, we examine prediction errors for larger and smaller than median-sized firms in the total sample and each of the three subsamples. In both the total sample and the subsamples, it is clear that the overall results are attributable to the smaller firms, where the CAPE is 0.0104 and significant at the 0.05 level, while the CAPE for the larger firms is 20.0008 and not statistically different from 0. For the smaller firms, although only appointments of commercial bankers are statistically significant (CAPE50.0128,t52.55), the results are qualitatively similar for investment bankers (CAPE50.0115,t51.65). The CAPE is much smaller for directors from insurance companies (CAPE5 0.0033,t5 0.52).

The empirical results in Table 3 lend support for the hypothesis that outside directors from financial institutions are more valuable for smaller firms, perhaps because smaller firms have less access to financial markets or are in greater need of the financial expertise supplied by financial outside directors. One alternative explanation is that these announcements have less effect for large firms simply because large firms are in the news more frequently.

different information than the appointment of an investment banker. For example, the appointment of a commercial banker may signal that the firm is considering an increase in financial leverage, consistent with non-negative abnormal returns. The appointment of an investment banker might signal that the firm is considering putting itself up for sale, because both an equity issue and an acquisition would be expected to be associated with negative abnormal returns.

We conducted regression analysis to simultaneously account for firm size, event contamination (other announcements occurring on or near the director announcement date), and whether the new director is a replacement or expands the board. After controlling for these variables, we found no significant differences in abnormal returns across the different types of directors. The coefficient on the natural logarithm of the market value of equity is negative and statistically significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed test), in keeping with previous results. In the interest of brevity, regression results are omitted.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we examined shareholder wealth effects associated with the appoint-ment of an outside director who is an executive of a commercial bank, insurance company, or an investment bank to determine if one type of financial director is viewed more positively than another. Consistent with previous research, we find that the appointment of a financial director is, on average, associated with increased firm value. These increases are attributable to smaller firms, suggesting that smaller firms appoint financial outsiders to their boards to gain access to financial markets or to obtain specific financial expertise in an efficient manner. We found no significant differences between the three types of financial executive. Interestingly, investment bankers tend to be invited to join the boards of much smaller firms than commercial bankers or insurance company executives, perhaps in an effort to gain access more economically to financial markets.

Although there is anecdotal evidence that boards of directors are becoming more assertive in their monitoring of management teams, there are no empirical studies comparing previous boards with those of the late 1990s. Since there have been no legal changes to the responsibilities and authority of boards of directors, we believe that results from the 1981–1985 period are still relevant.

This research is consistent with the hypotheses that board composition is a factor in corporate valuation and that outside directors in general, and financial directors in particular, are selected in the interests of shareholders.

Notes

Shivdasani (1993, tender offers), and Singh and Harianto (1990, golden para-chutes).

2. There is no significant difference in means or medians for appointments of insurance company executives versus commercial bankers.

3. We use standardized abnormal prediction errors only to obtain a well-specified and powerful significance test of the event-study itself (see Brown and Warner, 1985). However, nonstandardized abnormal prediction errors are economically more meaningful and are used for the discussion and for subsequent regression analysis.

References

Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (1995). Relationship lending and lines of credit in small firm finance.

Journal of Business 68(3), 351–382.

Bhagat, S., & Black, B. (1997). Do independent directors matter? Unpublished manuscript, University of Colorado.

Booth, J. R., & Deli, D. N. (1998). On executives of financial institutions as outside directors. Unpublished manuscript, Arizona State University.

Brickley, J. A., Lease, R., & Smith, Jr., C. W. (1988). Ownership structure and voting on antitakeover amendments.Journal of Financial Economics 20(1/2), 267–291.

Brickley, J. A., Coles, J. L., & Terry, R. L. (1994). Outside directors and the adoption of poison pills.

Journal of Financial Economics 35(3), 371–390.

Brown, S. J., & Warner, J. B. (1985). Using daily stock price returns: the case of event studies.Journal of Financial Economics 14(1), 3–32.

Byrd, J., & Hickman, K. (1992). Do outside directors monitor managers? Evidence from tender offer bids.Journal of Financial Economics 32(3), 195–222.

Cochran, P. L., Wood, R. A., & Jones, T. B. (1985). The composition of boards of directors and the incidence of golden parachutes.Academy of Management Journal 28(3), 664–671.

Cotter, J. F., Shivdasani, A., & Zenner, M. (1997). Do independent directors enhance target shareholder wealth during tender offers?Journal of Financial Economics 43(2), 195–218.

Easterbrook, F. (1984). Two agency cost explanations of dividends.American Economic Review 74(4), 650–659.

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control.Journal of Law and Economics 26(2), 301–325.

Furtado, E. P. H., & Rozeff, M. S. (1987). The wealth effects of company initiated management changes.

Journal of Financial Economics 18(1), 147–160.

Gilson, R. (1990). Bankruptcy, boards, banks, and blockholders: evidence on changes in corporate ownership and control when firms default.Journal of Financial Economics 27(2), 353–389.

Hermalin, B. E., & Weisbach. M. S. (1988). The determinants of board composition.RAND Journal of Economics 19(4), 589–606.

Kosnik, R. D. (1990). Effects of board demography and directors’ incentives on corporate greenmail decisions.Academy of Management Journal 33(1), 129–150.

Lee, C. I., Rosenstein, S., Rangan, N., & Davidson III, W. N. (1992). Board composition and shareholder wealth: the case of management buyouts.Financial Management 21(1), 58–72.

Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1994). The benefits of lending relationships: evidence from small business data.Journal of Finance 49(1), 3–38.

Rosenstein, S., & Wyatt, J. G. (1990). Outside directors, board independence and shareholder wealth.

Journal of Financial Economics 26(2), 175–191.

Shivdasani, A., & Yermack, D. (1997). The hand-picked board. Unpublished manuscript, Michigan State University.

Singh, H., & Harianto, F. (1989). Management-board relationships, takeover risk, and the adoption of golden parachutes.Academy of Management Journal 32(1), 7–24.